Last week, the Education and Employment Legislation Committee of the Australian Senate (our upper house)…

I feel good knowing there are libraries full of books

Today’s blog might appear to be something different but in fact is more of the same. There was an article in the New York Times recently (October 10, 2010) – The Crisis of the Humanities Officially Arrives – by US academic Stanley Fish, which discussed the growing demise of the humanities in our universities. While the debate is about the role of the humanities specifically, the points Fish makes about how we appraise the value in education resonates more broadly to a consideration of the role of educational institutions and human activity in general. One of the vehicles the neo-liberals use to promote their anti-intellectual agenda is the false claims that governments are financially constrained. By appealing to this myth lots of questions about motivation are avoided. They promote the myth that some activity is “too expensive” or “not productive enough” and we are thus shoe-horned into that way of thinking. But I feel good knowing there are libraries full of books of poems and plays and stories and I know that sovereign government are not financially constrained. I might not be able to defend the quality of a poem but I can certainly explain how the monetary system works. So you poets and playwrights under threat – come aboard and learn about fiscal policy and the monetary system and spread the word.

The neo-liberal era has successfully imposed a very narrow conception of value in relation to our consideration of human activity and endeavour. We have been bullied into thinking that value equals private profit and that public life has to fit this conception. In doing so we severely diminish the quality of life. The attack on the humanities is a symptom of this trend. So the first line of attack for those wanting to defend the libraries and the activities that lead to them accumulating more poems and plays is to expose the lies about the fiscal constraints.

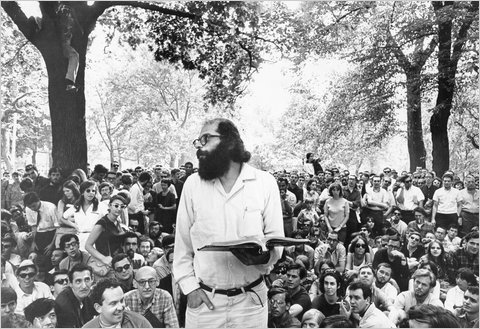

Allen Ginsberg’s famous poem Howl is now the basis of a movie of the same name that has been showing in cinemas. Here is a nice photo memory from 1966 where Ginsberg was reading his uncensored poetry to lots of beats in Washington Square Park, New York (Source). These were days when an appreciation of the “value” of the humanities was clear.

What that value was is unclear but society considered it important to have such activities within our universities and in our streets. Times have changed.

In the New York Times article mentioned in the introduction, Stanley Fish writes that while some are speculating about the possible demise of humanities, the reality

is that it had already happened …

He cites the closure of programs at a US university in “French, Italian, classics, Russian and theater programs”. He notes that in “1960s and ’70s, French departments were the location of much of the intellectual energy”.

The argument he presents is becoming increasingly familiar to academics such as me who eschew public policy benchmarks based on private “market calculus”.

Fish says that:

… the first thing to go in a regime of bottom-line efficiency are the plays.

And indeed, if your criteria are productivity, efficiency and consumer satisfaction, it makes perfect sense to withdraw funds and material support from the humanities – which do not earn their keep and often draw the ire of a public suspicious of what humanities teachers do in the classroom – and leave standing programs that have a more obvious relationship to a state’s economic prosperity and produce results the man or woman in the street can recognize and appreciate.

These benchmarks – summarised by the obscene managerial talk of KPIs – now rule Australian universities as they do elsewhere. They reflect the rise of neo-liberal constructs and their application to all aspects of human activity.

I read a book many years ago by Harry Braverman – Labor and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century (New York, Monthly Review Press, 1974) – which resonates in this debate.

At one point Braverman says (pages 170-71):

Thus, after a million years of labour, during which humans created not only a complex social culture but in a very real sense created themselves as well, the very cultural-biological trait upon which this entire evolution is founded has been brought, within the last two hundred years, to a crisis, a crisis which Marcuse aptly calls the threat of a “catastrophe of the human essence”. The unity of thought and action, conception and execution, hand and mind which capitalism threatened from its beginnings, is now attacked by a systematic dissolution employing all the resources of science and the various engineering disciplines based upon it. The subjective factor of the labour process is removed to a place among its inanimate objective factors. To the materials and instruments of production are added a “labour force”, another “factor of production”, and the process is henceforth carried on by management as the sole subjective element.

And progressively, these “labour processes” (market-values) subsume our whole lives – sport, leisure, learning, family – the lot. Everything becomes a capitalist surplus-creating process.

If we judge all human endeavour and activity by whether they are of value in a sense that we judge private profit making then we will limit our potential and our happiness.

Imposing a mainstream economics textbook model of the market as the exemplar of how we should value things is deeply flawed. Even within its own logic the model succumbs to “market failure”. The existence of external effects (to the transaction) means that the private market over-allocates resources when social costs exceed social benefits and under-allocates resources to this activity when social costs are less than social benefits.

The bean-counters have no way of knowing what these social costs or benefits are and so the decision-making systems become more crude – how much money will an academic program make relative to how much it costs in dollars? In some cases, this is drilled down to how much money an individual academic makes relative to his/her cost? This is a crude application of the private market calculus.

It is a totally unsuitable way of thinking about education provision. It has little relevance to deeper meaning and the sort of qualities which bind us as humans – to ourselves, into families, into communities, and as nations. I imposes a poverty on all of us by diminishing our concept of knowledge and forcing us to appraise everything as if it should be “profitable”.

The textbook model also presupposes that the consumer is always prescient – “sovereign” in the terminology that our students are forced to digest. This means that the supplier of a good or service has to tailor the offering to the preferences of the consumer who can shift between firms to get the best deal. This is the way in which the stylised (non-existent) textbook model of perfect competition achieves its claims to optimal resource allocation.

However, in the case of education, how can the child know what is best? How can they meaningfully appraise what is a good quality education and what is a poor quality education? The fact that the funding cuts have led to a stream of fly-by-night education providers in Australia who have left thousands of students stranded when they have gone broke is evidence of the failure of a market model.

The reality is that children do not demand programs. The universities are increasingly pressured by politicians (via funding) and corporations (via grants etc) to tailor the programs to the “market” agenda. I discuss this below when I consider the 1976 book Schooling in Capitalist America.

Higher education can only ever be a supply-determined activity and at that point the “market model” breaks down irretrievably.

Please read my blog – Defunct but still dominant and dangerous – where I discuss the Theory of Second Best, which undermines the legitimacy of applying the perfectly competitive textbook model is practical situations.

Stanley Fish goes on to discuss the ways in which we might defend the humanities which include placing restrictive rules (the so-called “core requirements”) on students so that they have to study certain (unpopular) subjects and therefore push resources into these areas which would die under a system of consumer (student) sovereignty.

He says:

But keeping something you value alive by artificial, and even coercive, means … is better than allowing them to die, if only because you may now die (get fired) with them, a fate that some visionary faculty members may now be suffering. I have always had trouble believing in the high-minded case for a core curriculum – that it preserves and transmits the best that has been thought and said – but I believe fully in the core curriculum as a device of employment for me and my fellow humanists.

But he acknowledges that the era of such “protection” is over and so he seeks new ways to defend the humanities. In that regard, he eschews the typical claims that “the humanities enhance our culture; the humanities make our society better” because:

… those pieties have a 19th century air about them and are not even believed in by some who rehearse them.

I was talking with someone who knows much more about these matters than me this morning and she pointed out to me the irony of recent trends in the humanities towards promoting post-modern relativist thinking. According to that now popular approach there is no intrinsic value in anything – it is all relative. So it becomes very hard if you work with a post-modern bent to actually defend your “value” to anyone. It is all relative after all. Go away and contemplate your navel somewhere else.

So one of the challenges of the humanities and all of us is to reconsider these questions of value – of worth – and of how we consider what being “productive” is.

I wrote a paper (with some colleagues) in 2003 comparing a Job Guarantee to an income guarantee. You can read the Working Paper version for free and it was not much different from the final published document.

We argued that the future of paid work is clearly an important debate given the declining opportunities that the “market economy” provides. The traditional moral views about the virtues of work – which are exploited by the capitalist class – need to be recast. Clearly, social policy can play a part in engendering this debate and help establish transition dynamics. However, it is likely that a non-capitalist system of work and income generation is needed before the yoke of the work ethic and the stigmatisation of non-work is fully expunged.

The question is how to make this transition in light of the constraints that capital places on the working class and the State. BI advocates think that their approach provides exactly this dynamic.

Clearly, there is a need to embrace a broader concept of work in the first phase of decoupling work and income. However, to impose this new culture of non-work on to society as it currently exists is unlikely to be a constructive approach. The patent resentment of the unemployed will only be transferred to the “surfers on Malibu”!

Social attitudes take time to evolve and are best reinforced by changes in the educational system. The social fabric must be rebuilt over time. The change in mode of production through evolutionary means will not happen overnight, and concepts of community wealth and civic responsibility that have been eroded over time, by the divide and conquer individualism of the neo-liberal era, have to be restored.

Part of this social transition – to changing the way we value human activity and time use – will require a strong humanities presence in our education system. It is much harder to construct the humanities in a market model and that is why it is under attack. But equally, that is why it has to be a vanguard leading our societies into a new “non-financial” appraisal of worth and value.

In his quest for credible defensive strategies for the humanities, Fish says:

And it won’t do to argue that the humanities contribute to economic health of the state – by producing more well-rounded workers or attracting corporations or delivering some other attenuated benefit – because nobody really buys that argument, not even the university administrators who make it.

While it is clear that well-educated workers are important for firms that should never be the criterion upon which we justify the support of our higher education institutions. Those sort of arguments may be applied to vocational training institutions but not our educational institutions.

Part of the attack on our universities in the neo-liberal era has been to blur the distinction between training and education – and by way of pursuing the lowest common denominator – subjugate the educational elements of our tertiary systems to the training elements. The rise of “business schools” over the last twenty years is the obvious example.

These schools provide little in the way of education. They have systematically attacked and downgraded the traditional educational disciplines of economics for example. In place of these more “difficult” learning tracks, universities have introduced “training” course in business which are nothing short of comical in their intellectual depth. It should be noted that I am making no comment here about the institution where I work. I am talking about sector-wide trends and specific trends within universities can be easily researched and you don’t need me to articulate them for you.

I also have a tension here of-course. The way economics has been taught in the last 30 years is a disgrace – having bowed over to neo-liberalism almost entirely. But the fact remains that the discipline has pretensions to being more than just a vocational pursuit.

So what does Fish propose as the way to defend the humanities? He says:

The only thing that might fly – and I’m hardly optimistic – is politics, by which I mean the political efforts of senior academic administrators to explain and defend the core enterprise to those constituencies – legislatures, boards of trustees, alumni, parents and others – that have either let bad educational things happen or have actively connived in them. And when I say “explain,” I should add aggressively explain – taking the bull by the horns, rejecting the demand (always a loser) to economically justify the liberal arts, refusing to allow myths (about lazy, pampered faculty who work two hours a week and undermine religion and the American way) to go unchallenged, and if necessary flagging the pretensions and hypocrisy of men and women who want to exercise control over higher education in the absence of any real knowledge of the matters on which they so confidently pronounce.

I liked this tack.

The university system has become very defensive as the neo-liberal dominance and values have been imposed on it. At the top, the management class is now a new breed – enjoying very high salaries and seeking to appease the bureaucrats and corporate interests alike. They have imposed what they see as the corporate model onto the institutions although one could argue if they were truly out in the “market” their tenure might be short given the performances of some of their institutions.

Far from resisting the funding cuts imposed upon them by successive neo-liberal governments, which would have made the cuts a political issue, the universities have followed the agenda set by the governments which includes imposing this corporate model onto their activities.

The participative system of management that we used to enjoy in universities has given way to the imposition of professional managers at every level. This has eroded the “sense of ownership” among faculty and reduced morale significantly.

The managers are increasingly supported by “bean-counters” in finance who often seem to lose track of the specific industry they are working in and see their role to reduce costs (except their own bonuses) without regard to effect. They used to support academic activity but now seek to rule over it.

The staff of the universities have also become compliant and stifled as the threat of job loss is now real. You will find very few academics these days who will publicly criticise governments or their own sector. I read somewhere a few weeks ago that many academics are scared to write blogs for fear of coming into conflict with the management of their institutions.

The KPI-driven system has also reduced traditional concepts of respect and loyalty. In the past, a brilliant scholar in the humanities would be lauded and universities would long to maintain their relationship to that person long after they had opted for formal retirement. Resources were made available to these emeritus scholars and respect maintained.

The bean-counter mentality that is seeing the humanities under attack now considers the academic human resources in very narrow terms – how much money will they bring into the institution? – and the idea of valuing a person for life, long after they retire and stop bringing in money is diminishing.

Of-course, the bean-counter mentality is applied all through a person’s career now and is one of the main reasons the humanities is being attacked.

So all of us who care have to come out and fight against the application of private market calculus to our universities.

A good starting point would be as Fish says to challenge the “pretensions and hypocrisy of men and women who want to exercise control over higher education”. Fish notes that the guy who is pushing the cuts to humanities at the US university he examines “is without a doctoral degree and who has little if any experience teaching or researching”. There are many examples of these “new managers” who have not acquired PhDs and the maturity that this brings.

The crisis in our higher education institutions has been a long-time coming and reflects part of the fall-out of the neo-liberal dishonesty about the financial capacity of national (sovereign) governments.

This was the opening paragraph in the submission by Universities Australia (the peak body representing universities) to the 2008 Bradley Review into higher education in Australia:

Universities in Australia are at a ‘tipping-point’. The sector continues to have many strengths, including expanded enrolments, development of a major international education industry, excellent student evaluations and research performance well ahead of our size. Nevertheless a dozen plus years of neglect have seen the student-staff ratios blow out, serious degradation of infrastructure and unsustainable stresses on staff. The academic workforce is ageing as academic life becomes less attractive to graduates. We are not educating all the highly skilled workers we need to be a competitive country in the knowledge economy of the 21st century. Our universities are dangerously dependent on the income from international students, a market which is fragile and unpredictable in the medium term.

I see my role in defending the humanities in terms of advancing the principles of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) which clearly demonstrate that all the financial arguments used by the government and their management class are false.

There is no financial argument for attacking the humanities. There is no financial constraint on government fully funding higher education. Whether the government should be funding higher education should be debated on different grounds and is a legitimate debate – as I note below.

But there is no legitimacy in the argument that it cannot afford to fund universities and so tough decisions need to be taken. That is a false agenda and unfortunately it dominates public policy and leads to these aberrant dynamics where market-based calculus is introduced to aid resource allocation.

The parallels resonate across the public policy domain. For example, we are told continuously that there are unsustainable pressures on the government’s budget coming as the population ages and the dependency ratios rise.

From a MMT perspective, the fiscal component of the debate is irrelevant. While we are told that these future needs will impose “heavy costs” on the national budget the reality is that we cannot meaningfully define costs in terms of budget outlays. Concepts such as heavy costs or soaring deficits are irrelevant concepts devoid of meaning.

There is no sense to the notion that public education or public health should “make profits”.

The only way that these sorts of debates will progress, however, is to take them out of the fiscal policy realm where they are largely inapplicable and start talking about rights and higher human values and what different interpretations of these rights and value concepts have for real resources allocations and redistributions.

For example, whether a nation can afford first-class health care depends only on the real resources that are available. Most nations can clearly afford that level of care for all of its citizens. There is never a financial constraint on the national government (where it is sovereign) from providing that level of health care. Subject to real resource availability, the only issue then is political.

The idea that the public fiscal position has to “seek savings” to make fund future spending (on health care and other programs) is a fundamental misconception that is often rehearsed in the financial and popular media.

This misconception has been driving the so-called intergenerational debate where governments are being pressured to run surpluses to pay for the retirement of baby boomers and the growing healthcare costs for them as they age further.

MMT demonstrated categorically that public surpluses do not create a cache of money that can be spent later. Currency-issuing governments spend by crediting bank accounts. There is no revenue constraint on this act. Government cheques don’t bounce!

Additionally, taxation consists of debiting a bank account. The funds debited are ‘accounted for’ but don’t actually ‘go anywhere’ nor ‘accumulate anywhere’.

In fact, the pursuit of budget surpluses by a sovereign government as a means of accumulating ‘future public spending capacity’ is not only without standing but also likely to undermine the capacity of the economy to provide the resources that may be necessary in the future to provide real goods and services of a particular composition desirable to an ageing or sick population.

By achieving and maintaining full employment via appropriate levels of net spending (deficits) the Government would be providing the best basis for growth in real goods and services in the future. In a fully employed economy, the intergenerational spending decisions on pensions and health come down to political choices sometimes constrained by real resource availability, but in no case constrained by monetary issues, either now or in the future.

All governments should aim to maintain an efficient and effective medical health system. Clearly the real health care system matters by which we mean the resources that are employed to deliver the health care services and the research that is done by universities and elsewhere to improve our future health prospects. So real facilities and real know how define the essence of an effective health care system.

Clearly maximising employment and output in each period is a necessary condition for long-term growth. It is important then to encourage high labour force participation rates and maintain job opportunities for older workers. There is a strong correlation between unemployment and health problems.

Anything that has a positive impact on the dependency ratio is desirable and the best thing for that is ensuring that there is a job available for all those who desire to work.

But this is about political choices rather than government finances.

The ability of government to provide necessary goods and services to the non-government sector, in particular, those goods that the private sector may under-provide is independent of government finance. Any attempt to link the two via erroneous concepts of fiscal policy ‘discipline’, will not increase per capita GDP growth in the longer term.

The reality is that fiscal drag that accompanies such ‘discipline’ reduces growth in aggregate demand and private disposable incomes, which can be measured by the foregone output that results. Fiscal austerity does help low inflation because it acts as a deflationary force relying on sustained excess capacity and unemployment to keep prices under control. Fiscal discipline is also claimed to increase national savings but this equals reduced non-government savings, which arguably is the relevant measure to focus upon.

Please read the following blogs – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3 – for further information on these points.

These argument also apply to our higher education system.

In general, the neo-liberal era has led to a loss of value of the capacities of people and the broad qualities that people of diverse interests and talents bring to the rest of us.

Case for university fees

In the final report of the Bradley Committee we read:

Total revenue to the sector has grown dramatically in the last 10 years from $10.2 billion in 1996 to $16.8 billion in 2007 (in real terms). The last major reforms of the funding arrangements for the sector were introduced in 2003 and provided an increase in investment in the sector by Government of $11 billion over 10 years. In spite of this injection of funds in the last four years, Commonwealth funding per subsidised student in 2008 was about 10 per cent lower in real terms than it was in 1996 … This was the result of a combination of direct cuts, constrained indexation and shifting of the balance towards higher student contributions.

So the sector has been squeezed by government cutbacks and the increased user-pays nature of higher education.

While a sovereign government is not financially constrained and therefore the provision of “free” tertiary education is not a financial question there still remains a case where students should pay fees for access.

This has been a long-standing debate in the Australian context where fees were abandoned in the early 1970s by a “Labor” government as an alleged equity measure. As the neo-liberal era unfolded (from the 1980s onwards) various fees have been increasingly imposed.

As of now, it is clear that Australian fees are now among the highest in the world (see Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) 2008b, Education at a Glance 2008: OECD Indicators, OECD, Paris).

The Bradley Committee report said:

There has also been a major policy shift towards increasing the contribution students make to the costs of their tuition. This approach recognises the private as well as public benefits of higher education and the advantaged position of higher education graduates.

I agree with this statement. It is often argued that the progressive left position is that university fees stop poor students from participating in higher education. The reality is somewhat different.

It is clear that the returns to higher education are predominantly private – with graduates enjoying superior access to employment opportunities and higher lifetime earnings. There are social returns but these are dominated by the gains that are “privatised” by the individuals. So the question that progressives have to ask is whether they want the government sector subsidising the rich!

By abandoning fees, a fully public-funded higher education system leads to a massive redistribution of resources from poor to rich. This arises because the participation of lower-income families in higher education in Australia (and elsewhere) is still very restricted. So in a free system, the rich are denied the choice between a family ski holiday in Aspen and a year’s tuition fees for their child – they can have both. Whereas the poor kid doesn’t even get to make that choice – they can have neither.

In a free system, the higher-income parents can pump a lot of resources into private secondary schooling which has higher success rates (but probably less overall educational value – another debate!) and then enjoy the public subsidy for higher education.

I read a book when I was a post-graduate student by Dutch economist Jan Pen (Income Distribution, 1971, Penguin) where he wrote that:

Parents are advanced secret agents of the class society.

This conditioned my thinking on higher education significantly and I realised that it was crucial that the public effort was better placed targetting merit in low-income neighbourhoods at an early age. The message from Pen was that the damage was done by the time the child reached their teenage years.

So the progressive claim that the imposition of fees at the university entry point discouraged disadvantaged children from participation and that abandoning those fees was an equity measure was based on a poor understanding of the constraints. The poor children rarely get to the point where such a choice was to be made.

They are long gone from the education system and increasingly in this neo-liberal era where we waste the potential of our youth and allow them to be idle in unemployment or underemployment (poorly paid, unstable casual jobs) they are not even gaining access to job-specific skill development and workplace experience.

In that book, Pen also introduced his famous Parade of the Dwarfs. There was an interesting article in the Atlantic Magazine in 2006 about this – The Height of Inequality – which traced how the productivity gains in the US had been siphoned off by the few at the top-end of the income distribution.

The Atlantic Magazine article described Pen’s Parade as follows (and provided this graphical depiction:

Suppose that every person in the economy walks by, as if in a parade. Imagine that the parade takes exactly an hour to pass, and that the marchers are arranged in order of income, with the lowest incomes at the front and the highest at the back. Also imagine that the heights of the people in the parade are proportional to what they make: those earning the average income will be of average height, those earning twice the average income will be twice the average height, and so on. We spectators, let us imagine, are also of average height …

As the parade begins … the marchers cannot be seen at all. They are walking upside down, with their heads underground-owners of loss-making businesses, most likely. Very soon, upright marchers begin to pass by, but they are tiny. For five minutes or so, the observers are peering down at people just inches high-old people and youngsters, mainly; people without regular work, who make a little from odd jobs. Ten minutes in, the full-time labor force has arrived: to begin with, mainly unskilled manual and clerical workers, burger flippers, shop assistants, and the like, standing about waist-high to the observers. And at this point things start to get dull, because there are so very many of these very small people. The minutes pass, and pass, and they keep on coming.

By about halfway through the parade … the observers might expect to be looking people in the eye-people of average height ought to be in the middle. But no, the marchers are still quite small, these experienced tradespeople, skilled industrial workers, trained office staff, and so on-not yet five feet tall, many of them. On and on they come.

It takes about forty-five minutes-the parade is drawing to a close-before the marchers are as tall as the observers. Heights are visibly rising by this point, but even now not very fast. In the final six minutes, however, when people with earnings in the top 10 percent begin to arrive, things get weird again. Heights begin to surge upward at a madly accelerating rate. Doctors, lawyers, and senior civil servants twenty feet tall speed by. Moments later, successful corporate executives, bankers, stockbrokers-peering down from fifty feet, 100 feet, 500 feet. In the last few seconds you glimpse pop stars, movie stars, the most successful entrepreneurs. You can see only up to their knees … And if you blink, you’ll miss them altogether. At the very end of the parade … the sole of … [the last person] … is hundreds of feet thick.

A free higher education system just reinforces this inequality. Public intervention has to come early in a child’s life to imbue them with the value of education and to overcome (if present) the negative attitudes that the lower-income parents may instil in their children. Resources have to be continually made available in poor neighbourhoods to ensure the children maintain contact with the educational system and gain a thirst for learning.

As the child progresses through primary and secondary education, public schooling should be of the highest quality possible. Well resourced, liberal in value and motivational. It should not be based on “market-values”. The pursuit of music, poetry, literature are all aspects of a high quality education.

Public support from families at this stage (means-tested) is essential – to ensure children remain at school. The goal is to ensure that the participation in higher education goes to the brightest students irrespective of family income.

The provision of a Job Guarantee for parents struggling with their own labour market viability in a hostile capitalist system would also help reduce the intergenerational disadvantage that persistent unemployment and underemployment clearly brings.

I was also influenced as a post-graduate by the 1976 Bowles and Gintis book – Schooling in Capitalist America.

In that book, several propositions were advanced including:

… that schools prepare people for adult work rules, by socializing people to function well, and without complaint, in the hierarchical structure of the modern corporation …

that parental economic status is passed on to children in part by means of unequal educational opportunity, but that the economic advantages of the offspring of higher social status families go considerably beyond the superior education they receive …

the evolution of the modern school system is not accounted for by the gradual perfection of a democratic or pedagogical ideal. Rather, it was the product of a series of conflicts arising through the transformation of the social organization of work and the distribution of its rewards. In this process, the interests of the owners of the leading businesses tended to predominate but were rarely uncontested.

You might also be interested in this 2001 reflection by the authors – Schooling in Capitalist America Revisited – where they summarise their earlier work and consider their current position.

The relevance of their work – which I think holds up pretty well in the subsequent developments since it was published – is that if we want a truly progressive, human-enriching education system then we have to eschew the imposition of “market-based” values and influences. To some extent the promotion of the “unproductive” (-: humanities helps to advance such an agenda.

It is harder to shoe-horn poetry into the private calculus of profit and much easier to promote it as an incendiary, provocative, challenging pursuit of time.

What is the use of it? Answer: in relation to what?

But all of this creates a tension in me about whether education is a “product” or not. I don’t think it is and should not be conceived in those terms. But it remains true that participation in higher education is highly skewed towards children from better-off families and that the results of that participation perpetuate the inequality across generations.

The tension is clear. The imposition of user-pays with means-tested support for children from disadvantaged backgrounds is an equity argument – to stop the poor subsidising the rich. It is not related to any notion of a financial constraint on government. A sovereign government could afford to fund the participation of all.

Without fees and without significant funding of pre-school, primary and secondary education in disadvantage areas, the growth in higher education involves increasingly going out into the “tails” of the merit distribution applicable to the middle-classes and higher.

In this context, I invoke a meritocratic criterion. While I advocate that governments support the maximisation of human potential for all and introduce policies that ensure all citizens and their children have access to education and learning, the reality is that higher education is not suitable for all talents. Some children are better suited to vocational training.

Moreover, I do not support extensive public subsidies of essentially private activities and in that sense the user-pays system at the higher education level is applicable.

So I separate the need to keep our universities fully funded and supportive of the humanities from the equity arguments about user-pays. It is a complex argument but once you separate the funding argument (there is no argument!) from the equity-driven user-pays argument you can appreciate the intent.

Conceiving education as a product then leads to the textbook claim that “consumers are sovereign” meaning that the supplier has to provide what the consumer wants or they will lose their business to competitors. This conception has in practice been very damaging to our higher education system.

It has led to increasingly legalistic demands by students on the system for superior results. It has led to the demolition of certain courses etc which are deemed not of “interest” to students.

As export education expanded in the face of cutbacks in government funding it became clear that the cultural norms of the “markets” that we were supplying into were different. The concept of open debate was not necessarily present. More “functional” (read: market-oriented) values were demanded. Lowest common denominator became the direction of the system.

It has also led institutions themselves prostituting their programs to the market.

By challenging the erroneous arguments about fiscal constraints it becomes easier to appraise these deviant trends for what they are – an attack on our broader values and quality of education. There is no need for the higher education to “export” its services. It certainly may want to do this for development purposes (to aid poorer nations etc) with due respect for cultural differences etc but it should never have to do this for financial reasons.

Conclusion

While this blog was broader than usual the message is the same – the neo-liberals have persuaded us that national governments have financial constraints and that every activity has to be evaluated within the framework of private calculus that a corporate entity aiming to pursue value for their private owners would use.

This framework is already flawed by the existence of external effects (to the transaction) which means that the private market over-allocates resources when social costs > social benefits and under-allocates resources to this activity when social costs < social benefits.

But beyond that is a sense that the framework has little relevance to deeper meaning and the sort of qualities which bind us as humans – to ourselves, into families, into communities, and as nations.

The residual damage of the neo-liberal approach extends well beyond the huge economic losses it imposes on us in the form of persistently high unemployment and underemployment. The material poverty that it has inflicted on cohorts in our societies is one thing – abhorrent nonetheless. But it is also imposing a poverty on all of us by diminishing our concept of knowledge and forcing us to appraise everything as if it should be “profitable”.

Ultimately, sometime after it is too late, some memories will recall the days when this wasn’t so and when the bean counters were strait-laced accountants with bow-ties and those metal expanding arm things that held shirt-sleeves in check.

And to put us into a good frame for the weekend coming (maybe to make the Saturday Quiz appear meaningful) here is the first 10 or so lines of Ginsberg’s 1955 epic – Howl:

I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by

madness, starving hysterical naked,

dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn

looking for an angry fix,

angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly

connection to the starry dynamo in the machin-

ery of night,

who poverty and tatters and hollow-eyed and high sat

up smoking in the supernatural darkness of

cold-water flats floating across the tops of cities

contemplating jazz,

who bared their brains to Heaven under the El and

saw Mohammedan angels staggering on tene-

ment roofs illuminated,

who passed through universities with radiant cool eyes

hallucinating Arkansas and Blake-light tragedy

among the scholars of war,

who were expelled from the academies for crazy &

publishing obscene odes on the windows of the

skull,etc

The – Full Text.

Sure it is not Tennyson but it still is worth keeping alive and having students exposed to it.

Send it to some bean-counters at your university.

PS: despite the title of this blog I also love my Kindle now – it reduces the number of books I have to carry when I travel to “one”! But I still need authors and poets to create the content!

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back sometime tomorrow – even harder than last week!

That is enough for today!

I got a kindle for my birthday recently and it is fantastic. Reading on paper will seem obsolete soon!

“It is a complex argument but once you separate the funding argument (there is no argument!) from the equity-driven user-pays argument you can appreciate the intent.”

I appreciate the intent, but that argument applies to all education from day one. Not just to higher education.

Access to all education should be by merit and that includes good quality vocational training. It is entirely arguable that furthering your education is a ‘job’ and should receive the JG wage in the same way as any other ‘useful work’. That then determines what education you can afford.

Great post, When you say “I do not support extensive public subsidies of essentially private activities” I wonder whether if absolutely everyone got the same level of public subsidy (not just those in universities) then there would not be such an issue of unfairness. I get the impression that much of research (science, maths and engineering as much as arts) is valued much more by the participants than by other people and so could perhaps be viewed as private activity rather than as something that demands special financial reward. As such it kind of falls under those activities that might deserve the JG level of payment. My own personal preference is for everyone to get such a level of payment irrespective of whether they are doing anything that anyone else comprehends the value of. Such a system would be the ultimate guarantee of academic freedom.

I agree that if university teaching becomes molded to fit in with what are imagined to be the sensibilities of foreign students, then it becomes fairly pointless. I’m not sure that having a large number of foreign students always leads to that though. Some one I know used to teach law at a variety of UK universities and remarked at how Singaporean students tended to initially be taken aback by the irreverent deconstruction of the legal tradition that was at the heart of the teaching and yet nevertheless often became star students -pushing forward the analysis in seminars etc.

In biomedical science much of the funding comes from endowment funds such as the Wellcome Trust (in the UK) and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (in the USA). They fund in the nicest possible way from the point of view of the recipients. They are in essence large hedge funds that harvest money from the global economy by financial speculation (the Wellcome Trust received a £1B in 1987 and has made investment gains since then so that it now has £14B and pays out >£700M per year). The UK government wants much more university funding to be along such a model (I think the Ivy League US universities may get much of their income from endowment fund investment income). I feel that such a source of funding seems much less ethical than getting payment from foreign students.

I was struck by how in the pacific north west, native americans apparently used to have month long poetry recitals/dances etc. Even now people wonder at the art they produced. That pretty much shows that we can potentially support such a level of “pointless” activity in a non-coercive way.

My own college education occurred at a fine (what other kind is there?) Ivy League university (Brown) at about the time when these universities were, through generous financial aid, being opened up to the better students of the lower classes, myself included. I believe as such that I was probably (though unknowingly) at the beginning of the transition you are describing here, though clearly in its earliest stages, as there was still a sense of superiority present among those of us who chose liberal arts over those involved in the “purer” hard sciences.

I found myself confused after a bit, unable to identify any Thing that I was learning. Oh no, explained my brother, also a student there but several years ahead of me and in a hard science. Brown doesn’t teach us any Thing, he said, they teach us to think. We are not to “know” any answers; merely to know How to find them whenever we are called upon to do so. They are not trying to make us into engineers or historians or chemists; they are trying to make us into graduate students where we can become those things. How ridiculous, he continued, to think that anyone could become any of those things in a mere four years.

This was a marvelous revelation to me. I began to think of my brain much as a body builder thinks of his body; a series of distinct muscles to be individually trained to some level of perfection, not for their own sakes, but rather for the resulting beauty of the whole. I wanted to learn not engineering, not history, not chemistry, but rather How an engineer, How an historian, How a chemist thinks. My direction was to become the person who would bring these various highly-trained specialists together later in life to solve problems which would be greater than any of them individually could resolve. I found after a while that whenever I was confronted with a new problem, I would first think, How would an engineer think about this, How would an historian think about this, How would a chemist think about this, and I would select from these the several or many that would offer the most promising results, blending them together as only I and my liberal understands could do. And every time I did this and achieved some new goal, I would think how fortunate I was that I had chosen to grow my brain in that liberal tradition.

As I’ve mentioned, I was there during the start of this transition from learning Hows to learning Things, and so I consider myself familiar with both the “old ways” and the new. Obviously I have profound respect for the old. So I find it curious that the old is now considered just that: old; somehow no more than a too costly luxury. I can’t help but think however that back in the “old days”, when only the wealthy elite where allowed access to the finer levels of education, this idea that the classics and the liberal tradition was a too expensive luxury was never entertained. Indeed, when it was only available to the elites, it was not only not too expensive, it was demanded, and institutions that did not provide it were looked down upon as mere “trade schools”. Why then that only now as these things have become available to also lift the rabble from their ignorances has it suddenly become so critical that these new intellectuals justify themselves in the marketplace by knowing some narrower Thing? It seems not only that we are becoming ignorant, which of itself is no shame, but also that we are choosing to become so, which is.

P.S. Your title reminds me of the first book of Asimov’s Foundation Trilogy, in which the social historians gather copies of all the books and hide them away far from the expected ravages of a coming interplanetary war. They have no belief that these will be used any time within their lives, but hope only that perhaps in some future world they will be retrieved and the knowledge of the ages will be once again available to all.

Camden, New Jersey is a very poor, largely black adjunct to the far richer Philadelphia. Being next to each other but in a different state, much of what would have been Philadelphia’s poor go off to Camden’s slums seeking cheaper living. Camden’s severe financial problems are governmentally much further apart from the financial problems of Philadelphia than the width of the river that separates them would suggest, but suffice to say, there is little politically that Philadelphia can do to aid its poverty-stricken neighbor. This is often the case in the United States wherever major metropolitan areas span state lines. We have many Camdens.

This Camden, whose children rarely find a book under their Christmas trees, so constrained financially are their parents, has chosen to close their public library system. Apparently it cannot survive a cost benefit analysis. Tragic as this is, what they have chosen to do with the books therein is far worse. You see, rather than simply lock the doors and hope that in some future world they might once again find it possible and beneficial to employ a librarian or two, they have decided to sell those books off at whatever pennies they might command, and for those that will not command pennies, to toss them into dumpsters, to be crated away as just yesterday garbage. Apparently there is also no cost benefit to simply letting them lie in wait for future hopes.

The harm, especially to the children, of closing a city’s libraries is obvious enough, but to close them in a fashion such as Camden has chosen is to close them in a way where they can almost certainly never be opened again. It is a solution that only a neoliberal could love.

Ultimately, only necessity is likely to change any of this. When, due to increasing automation, many, or even most people are not needed for their labor, then we’ll get a more “Arts and Leisure”/post-scarcity society. What to do with all those people who have jobs which will, in fact, never come back due to automation? It’s been said many times in the past, but eventually we will reach a point where non-human labor is much cheaper than human labor, and we’ll have to make these choices. Attempting to get there by arguing about nebulous, and ultimately subjective values of these programs is not likely to go anywhere anymore.

Annoyingly in the UK the coalition has got the costs calibrated to earnings via the interest on the debt…great…then slashed public university funding so universities have less money when the amount of funding was about right, around 1/3 as in the UK around 2/3 of the benefit goes to the individual student and 1/3 to the nation/s.

Pupil premium for poorer children is great but the main problem is that kids growing up in the welfare underclass have no idea of what work/study is and are horribly behind before they get to school…my daughter attended an inner city pre-school and 40% of her intake couldn’t talk, let alone start read/writing…yet that school managed to get the kids up to the national average by the time they got to secondary school, phenomenal educational ‘value added’ but the school no longer exists, the victorian buildings demolished. Many of the places in the pre-school were taken up by middle class kids as the lower class parents didn’t appear interested. I have to add that we moved to said suburb in pursuit of space and better schools.

Dear Bill,

I would agree whole heartedly with the broad sweep of your article re the more pernicious effects of ‘neoclassicism’ in society and in education in particular; and the role MMT theory might play in offering better outcomes. Additionally I would note, the closer one gets to the centre of a cyclone, the simpler things become. I find it ironic at this point in human history when there are more education institutions on the face of this earth than ever before, that there is more ignorance (unconsciousness) than ever before. You are always way too polite to mention it in your blogs – but one day human beings will be forced to recognise just how stupid they have been in the fundamentals of providing food clothing shelter and security to their own species; let alone care for the rest of the planet and its denizens. Human beings in general, are way too cocky for their own good: vis – a little humility now and again (when the tsunamis come, a real cyclone strikes, or the shark bites) wakes everybody up for about five minutes – changes our perceptions on the value of being alive; then it’s back to being asleep as usual. I can support this view with a few simple observations:

• First of all, the human population on the face of this earth has exploded exponentially over the last few hundred years, and on current projections, and with current political economic climatic ecological fuel limitations on the food supply, the situation should be of deep concern for the species as a whole;

• There are more advances in health and related technologies than ever before – and yet there are more people dying unnecessarily of preventable diseases than ever before;

• There are more houses being built than ever before – and yet there are more people homeless, or living in abject poverty in shanties than ever before;

• There is more food grown than ever before – and yet there are more people malnourished or starving to death than ever before (especially women and children – men should hang their head in shame);

• Human beings are the only species on the planet that become unemployed;

• There are more clothes being manufactured than ever before – and yet there are more people living in rags than ever before;

• There is greater understanding in all of the human sciences than ever before – and yet there is more havoc wreaked by our own species on our own kind, and the environment, than ever before;

• There are greater developments in political understanding, statesmanship and international diplomacy than ever before – and yet there are more wars being fought than ever before;

• There has been more wealth created than ever before – and yet there is more greed, inequity, division and fragmentation than ever before;

• There are more religions than ever before – and yet there is more disagreement about the ‘One God’ and who’s side (it, she, he) is on than ever before;

• There is more communication around the globe than ever before – and yet there is more misunderstanding, misinformation, propaganda and lying than ever before;

• There is more art, music, literature, books, speeches being written; manuscripts, blogs, information, knowledge, opinions, intellection than ever before – and yet there is less inspiration, more confusion, more miasma in the world than ever before.

In short, there is more ignorance in the world than ever before. On any fair assessment, you would have to give the species on current reporting a definitive fail (F). I don’t need to be an academic to understand that. We have the know-how; but not the consciousness to implement it. Why is this so? Well, my take is:

1. In every human being there is ‘good’ and there is ‘bad’. These need not be defined by anything on the outside. We all know the feeling of ‘good’ (from which attributes like generosity, kindness and happiness flow of their own accord) and the feeling of ‘bad’ (from which attributes like anger, greed, jealousy, selfishness and separation flow of their own accord);

2. Every day, every moment of every day, with each breath – we choose (consciously or unconsciously), which of these we will be in touch with;

3. One of our most fundamental problems then, is ‘unconsciousness’;

4. It is also fundamentally true that anger begets only anger; greed only more greed; hatred only more hatred: whilst kindness begets kindness, and love begets love – this is a law of our own Nature;

5. When we are happy, content, in harmony – we use our intelligence accordingly: when we are in touch with our darker side, we use our intelligence accordingly – the world is a reflection of the battle that rages within;

6. The energy that drives every human being on the face of this earth is (in my experience) to be content, to touch the ‘goodness’ within and express it by any means through any avenue of human creativity and production – unconsciousness leads us to making wrong choices which lead inevitably to unhappiness;

7. If you want a better ‘xyz system’ then you must put human beings back in touch with their own better nature, and understand the value of consciously and consistently, staying in touch with that better nature – that is the fundamental education;

8. Human beings have not yet learnt through evolution and experience to harmonise their personalities within themselves, hence the conflict spills out to the outside and with each other – the real goal of education should be the goal evident in our evolution – control over the human personality by the consciousness that owns it – the first step is to connect to the ‘good’ within;

9. This is done through learning how to ‘feel’, not through learning how to think (which should also be taught) as a second priority, in harmony with the mental development, complementing the first;

10. What that ‘good’ within a human being actually is, I think of as the most challenging frontier left in human nature (we have done all of the stupid things).

Thanks Bill, cheers …

jrbarch

We have seen the decline of science, now the demise of humanities? What’s left?

“she pointed out to me the irony of recent trends in the humanities towards promoting post-modern relativist thinking. According to that now popular approach there is no intrinsic value in anything – it is all relative.”

IMO, post-modernism lies at the core of the decline of the humanities (as we know them). Though we talk about liberal arts, they are not the same as they were in, say, France in 1400. Modern humanities derive largely from the Enlightenment, and it is the Enlightenment that post-modernism opposes. It is ironic that neo-liberal economics should be involved in the demise of the humanities, as it, too, derives from the Enlightenment. A little post-modernism in economics might not be a bad thing. 😉

It seems to me that this reflects a broad cultural change, and I am not pessimistic. It does not, I think, represent the victory of the Bean Counters, even if they are gaining ascendancy. Rather, I think, some new Fusion (to use the musical term) will arise in time.

Something else that is going on is the changing nature of the University. Its role in loco parentis for “children” is diminishing. For one thing, the idea of the child that arose from the Industrial Revolution is changing. (It never made a good fit with adolescents, anyway.) For another, the nature of University students is changing, as more people return to school. Will the students run Universities again, as they did before the Industrial Revolution? Perhaps. That might even be a good thing. 🙂 The Humanities (as we know them) thrived when students did, even students who would be considered children today. Young people are not dummies, you know. 🙂

Benedict@Large, I studied in the Soviet Union schooling system and many points that Bill writes here resonate a lot with it. However I wanted to add to your point one from my own experience. I studied hard science stuff and there was one moment during my first semester which I can never forget. It was a class of linear algebra and analytic geometry (yes, I remember it all (-: ) and professor (a chronic drunkard btw as we all discovered later) asked the class about what we thought we would learn at the university. All types of answers were given. In the end he said: “You are here to learn how to learn and where to find what you need to learn”. After so many years it feels like it was yesterday. I will never forget it.

Benedict@Large: “Tragic as this is, what they have chosen to do with the books therein is far worse. You see, rather than simply lock the doors and hope that in some future world they might once again find it possible and beneficial to employ a librarian or two, they have decided to sell those books off at whatever pennies they might command, and for those that will not command pennies, to toss them into dumpsters, to be crated away as just yesterday garbage.”

Why not give them away? Christmas is coming up. 🙂 (Have an adopt a book week.)

Also see http://www.bookcrossing.com/ 🙂

The Pen passage was beautiful.

From a nytimes article, published in 2007, using 2005 data:

[The] top 300,000 Americans collectively enjoyed almost as much income as the bottom 150 million Americans. Per person, the top group received 440 times as much as the average person in the bottom half earned, nearly doubling the gap from 1980.

Sergei, “I studied in the Soviet Union schooling system and many points that Bill writes here resonate a lot with it.”

– I’m really keen to hear how. I’m so ignorant that I don’t know whether you are meaning that the soviet education system was an ideal or the opposit or something else. My ignorant impression was that in terms of producing people versed in mathematical skills (for instance), the soviet education system was the best in the history of humanity. That had made me question the whole value of education because the soviet union seemed to make such a hash of their transition from communism despite having such a well educated population. I’d be very keen to hear any thoughts about that.

jrbarch, I read in a recent National Geographic article about a hunter gather tribe in Tanzania that they have an ethos that if someone has a successful hunt, it is considered rude to personaly crow about the success. Not only is the meat shared equally but also the “glory”.

I think the root of the problems you describe is an unbridled effort by people to control and dominate other people. I wonder whether the way realityTV audiences vote (in programs such as big brother) is a window into real human nature in our own society. In realityTV programs such as big brother, it is people who try and manipulate and control other people who become the most unpopular with the public. What gets the most public loathing is underhand sneeky manipulation. I think our unneccessarily complex and expansive economic system is the ultimate example of underhand sneeky manipulation. I think our system rewards and empowers the very trait that is most unpopular with reality TV audiences.

I think your description of all the problems we face indicates that economics is the heart of the challenge we face. As you say we produce plenty, the problem is distribution. That is an economic problem. Current economics seems focussed on forcing more global inequality rather than reducing it. Until we can reverse that, things will only get worse.

Stone,

“I think the root of the problems you describe is an unbridled effort by people to control and dominate other people.”

Couldnt agree more, that is at least one major part for sure. A few weeks ago here in the US, Pres Obama had an interview where (it was supposed to have a faith based angle to the interview) he said that he saw himself as ‘his brothers keeper‘… interesting choice of words. I think of a zoo ‘keeper’, etc..

Resp,

Matt Franko “he saw himself as ‘his brothers keeper’… interesting choice of words. I think of a zoo ‘keeper’, etc..”-

One reason why I’m a fan of the “citizens’ dividend” as a way of conducting government spending is because of the change in attitude it might cause if all citizens overtly considered themselves and their fellow citizens as equal shareholders in the state. In the UK we have a large corporation called John Lewis Group that is entirely employee owned (as a relic of an eccentric private owner who in the 1920s donated it to the workforce). The CEO seems to view and treat his fellow employees quite differently than in typical companies (as I guess they decide whether to sack him). In principle presidents should have a similar view of their electorates but both the electorates and the rulers seem to loose sight of that.

Opir Music:”When, due to increasing automation, many, or even most people are not needed for their labor, then we’ll get a more “Arts and Leisure”/post-scarcity society.”

-You seem to have overlooked the fact that the expansion in the finance sector will more than make up for the amount of labor required :). For every farmer no longer required, two quantitive analysist jobs spring up. The grand visionary future is one of permant toil trying to outwit each other with arbitrage strategies or something like that.

stone, I cannot really discuss the internal workings of the schooling system in the Soviet Union but it was mostly likely one of the best in natural sciences. I do not know how professors got their tenure and what bureaucratic pressures they faced and clearly there were many positive as well as negative examples. However, overall it was all about people who lived their lives with this system and who never wanted to make money out of it. It was not their primary goal. If you have heard about Perelman, a Russian mathematician who turned down a $1m prize, then he is an example of mentality those people had. I remember many of professors from my physics degree but I can hardly remember anyone from the economics university which I also had “luck” to graduate from some years later.

You ask why transition happened so fast with such educational system. I would answer that transition was not fast and Perelman is not an exception but these people become a very rare breed. Educated people did not disappear overnight but they were educated in different terms. They had no grounds to challenge any economic theory. So they just adopted economic theory of neoliberalism without challenging it because neoliberalism was extremely good at presenting itself. People went from one extreme (planning system) to another extreme (market fundamentalism) without asking a single question. Psychology of neoliberalism is very primitive and it was very easy for neoliberalism to win this fight. It is pretty much the same way how the primitive and young psychology of western civilization wins against any other psychology (e.g. eastern) which are much older and much more developed.

So though I do not agree with all points that Bill makes here but many of them do resonate with me and the schooling system I studied in.

Sergei “I remember many of professors from my physics degree but I can hardly remember anyone from the economics university which I also had “luck” to graduate from some years later.”-

Was the economics university also in the soviet union before the fall of communism or was it somewhere else or after the fall of communism? I kind of think that their must be extremely important lessons to be learned from the way the soviet union collapsed.

stone, actually I had both, i.e. economics there and economics + business here 🙂

I am not sure whether there is anything to learn in terms of education from SU collapse or I do not understand what you mean. I started to think that psychology is the critical factor to look at if we (humanity) want to achieve anything. Western psychology is way too primitive for any serious task or even sustainable existence.

Sergei “Western psychology is way too primitive for any serious task or even sustainable existence.”-

Sergei, when you say “primitive”, is your meaning as in crude rather than as in ancient? Also when you say “psychology ” do you mean the academic subject of psychology or do you mean our western mentality about everything?

I suppose what I was struggling with trying to understand about the post soviet situation was why the soviet union didn’t just become like a large Finland with the lowest child mortality rate in the world etc etc. People used to say that Japan and Germany emerged to prosperity after World War II whilst Africa emerged to chaos after independence because Japan and Germany had such a well educated population. The soviet union had an even better educated population than Germany or Japan but at least initially looked to be taking the Africa route with increasing levels of poverty etc.