Regular readers will know that I hate the term NAIRU - or Non-Accelerating-Inflation-Rate-of-Unemployment - which…

Changes in labour force composition and full employment

The headlines this morning in Australia (economic policy wise) focused on the Government’s Sunday meeting where government departments in Canberra were instructed to find more spending cuts before Xmas as part of a renewed slash and burn of the Australian economy so that the Government can keep forecasting a budget surplus for the coming financial year. A few hours later, several major data releases from the Australian Bureau of Statistics came out, which showed that the Australian economy is slowing – fairly significantly. The latter clearly demonstrates the folly of the former. But try telling that to a government that preaches to us about its economic credentials yet designs and implements its major economic policy initiatives based, purely on what it perceives to be in its political best interest. It is wrong about the former and, as events turn out, will also not achieve the political capital it is aiming for. The spending cuts are causing the economy to slow, which is defeating its quest for surplus. As a result it will be damaged for “failing to keep its promise” even though that promise was the height of vandalism. That tells you how unsophisticated the policy debate and knowledge about economic matters is in this country. it is also clear that the Australian economy is a long way from full employment. So today I examine one of the arguments that the conservatives use to refute my last conclusion. I consider the argument that the increased involvement of females in the labour force over the last 30 years has pushed up the unemployment rate that we consider to be consistent with full employment to around five per cent. That claim is not tenable.

Melbourne Age economics correspondent, Peter Martin reported on the Razor Gang meeting yesterday in his article (December 3, 2012) – The deficit that stole Canberra’s Christmas.

He wrote that the:

… government has asked public servants to search for fresh spending cuts in the lead-up to Christmas in a new attempt to achieve a 2012-13 budget surplus.

The reality is that the economy is not growing as fast as the Budget estimates suggested in May 2012. The other reality is that the economy was never going to grow as fast as the Government predicted but by inflating the estimates they were able to engineer a forecasted budget surplus.

It is the same tactic as the IMF who continually inflate growth estimates while at the same time recommending fiscal austerity (in other words, seriously underestimating the negative impacts of the austerity).

Tax revenue is falling for the Australian government, mainly because the economy is stalling. Some structural issues with respect to the mining tax (when profit flows) has seen it raise virtually zero revenue.

The point is that the budget outcome is currently looking very much like a deficit of more than $A10-15 billion instead of the forecasted surplus of $A1.1 billion.

We should be happy that the deficit is not going to disappear because if the Government had achieved its dream then unemployment would be much higher and the economy would be heading for recession in 2013.

The fact that every time, the Government receives bad news with respect to its tax revenue, it claims it will cut spending even further, means that it is hell-bent on forcing that reality on the economy. Pro-cyclical fiscal policy changes is never warranted unless the economy is growing but still well below full employment.

Nothing could be further from the truth at present.

This week is a veritable data feast in Australia. Today, the ABS published three major series (see below) and tomorrow the RBA announces its latest monetary policy stance. On Wednesday, the September National Accounts come out and on Thursday, the November Labour Force survey results will be published.

However, seemingly oblivious to the negative results that are coming out from the ABS, the Government’s obsessive pursuit of a surplus continues.

Today, three data series came out – all negative.

First, the – Business Indicators, Australia – for the September quarter showed that both wages and profits fell.

The ABS said that (in seasonally-adjusted terms) that wages and salaries paid fell by 0.2 per cent in seasonally adjusted terms in the September quarter, while company profits fell by 2.9 per cent over the same period.

In the year to the September 2012, company profits fell by 13 per cent.

Second, the – Retail Trade, Australia – data for October 2102 confirmed that “Australian retail turnover was relatively unchanged (0.0 per cent) in October 2012”.

Finally, the ABS released their – Mineral and Petroleum Exploration – expenditure data for the September quarter 2012, which showed that the seasonally-adjusted figure fell by 14.7 per cent and the trend in the 12 months to September 2012 was down.

Mining investment has been driving domestic growth over the last few years as the contribution of the public sector has waned.

I expect to see the National Accounts data on Wednesday showing an economy that was slowing in the September quarter. Now is not the time for the Government to be further withdrawing spending from an economy that is starting to endure the tapering of record commodity prices and the significant private investment that chased the returns arising from the commodity price boom.

There was also an interesting article in the Melbourne Age today (December 3, 2012) – Dimming of the light on the hill – which I will discuss tomorrow. Its main thesis is that the current government has abandoned its historical commitment to full employment. The obsession with budget surpluses at a time when there is significant labour underutilisation exemplifies this abandonment.

In the 1980s, the mainstream economists started to argue that the full employment unemployment rate (FNUR) has risen from around 2 per cent in the 1960s to 8 per cent in the 1980s as a result of an alleged structural deterioration in the unemployment situation.

One line of argument was that welfare benefits were excessive and encouraging recipients to avoid taking jobs because the income support subsidised their idleness. This was at a time when the unemployment-vacancies ratio was around 10. But more importantly, at the time the unemployment started to climb from its full employment level (around 2 per cent) to its highs in the 1980s of around 8 per cent, there had been so significant changes in any income support schemes offered by the government in Australia.

A second line of argument related to claims that compositional changes in the labour force – specifically, the rise in participation of married women – had increased the aggregate unemployment rate.

At the time, I did a lot of work (and published several articles) on the topic, which was a direct outcome of the work I was doing for my PhD.

I argued that the persistent unemployment was sourced in demand deficiency and the structural arguments were just a ploy to argue against the use of aggregate macroeconomic policy to target full employment. Remember, that this was the beginning of the neo-liberal domination in economic thinking.

Demand deficient unemployment occurs when the number of people wanting gainful employment exceeds the number of vacancies being offered. The composition of the unemployed relative to the skills demanded is not the binding constraint.

Alternatively, the classification of unemployment as structural describes unemployment that results from imbalances in the supply of, and demand for, labour in a disaggregated context. A simple case arises which highlights the difference as to which constraint is promoting the unemployment. If at the aggregate level the number of unemployed is equal to the number of vacancies then (abstracting from seasonal and frictional influences) this unemployment would be termed structural.

Structuralists suggest that structural imbalances can originate from both the demand and supply sides of the economy. Technological changes, changes in the pattern of consumption, compositional movements in the labour force and welfare programme distortions are among the pot-pourri of influences listed as promoting the structural shifts.

The distinction between demand deficient and structural unemployment is usually considered important at the policy level. Macro policy will alleviate demand deficient unemployment, while micro policies are needed to redress the demand and supply mismatching characteristic of structural unemployment. In the latter case, macro expansion may be futile and inflationary.

In the 1980s, some economists (including yours truly) argued that structural changes may be cyclical in nature (the hysteresis effect). A prolonged recession may create conditions in the labour market which mimic structural imbalance but which can be redressed through aggregate policy without fuelling inflation.

The Brooking Institute in the US was also concerned with these structural arguments. George L. Perry published an interesting article in 1970 – Changing Labor Markets and Inflation – which sought a “non-natural rate hypothesis” explanation for the ostensible shift in the Phillip’s curve during the late 1960s.

He popularised the idea that the FNUR had increased because the share of groups with higher than average unemployment rates in the labour force had increased. The idea was that the demographic shifts were driving upward shifts in the aggregate unemployment rate because demographic groups that endured high unemployment rates had grown drastically as a proportion of the work force.

At the time that the arguments were being made – specifically, in relation to the dramatic rise in labour force participation of married woman as a result of the social changes that had occurred in the 1970s – the compositional change hypothesis could not be substantiated.

I published an article in 1987 where I analysed the argument in detail and concluded that:

… we reject the view that compositional changes in the labour force have been responsible for anything but the smallest increase in the aggregate unemployment rate (based on age-sex participation adjustments).

[Reference: W.F. Mitchell (1987) ‘What is the Full Employment Unemployment Rate? Some Empirical Evidence of Structural Unemployment in Australia, 1966 to 1986″, Australian Bulletin of Labour, 14(1), December, 321-337].

I decided to see what had happened since I wrote that article.

First, consider the following facts.

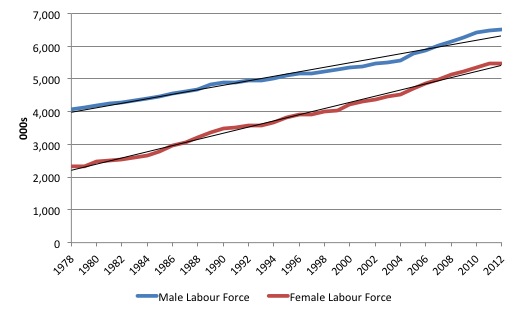

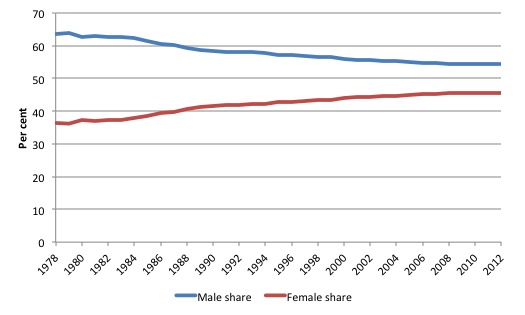

In August 1970, there were 3684.3 thousand males in the labour force (67.3 per cent of the total) and 1789.5 thousand females (32.7 per cent) making a total labour force of 5473.8 thousand.

By August 1978, there were 4073.1 thousand males in the labour force (63.6 per cent of the total) and 2330.5 thousand females (36.4 per cent of the total) , making a total labour force of 6403.7 thousand.

By August 2012, there were 6517.3 thousand males in the labour force (54.3 per cent of the total) and 5484.3 thousand females (45.7 per cent of the total) , making a total labour force of 12,001.6 thousand.

These are dramatic demographic shifts.

The following graph shows the respective male and female labour forces since August 1978. The black lines are the simple linear OLS trend.

The following graph shows the evolution of the male-female share in the labour force since 1978 (as measured at August each year).

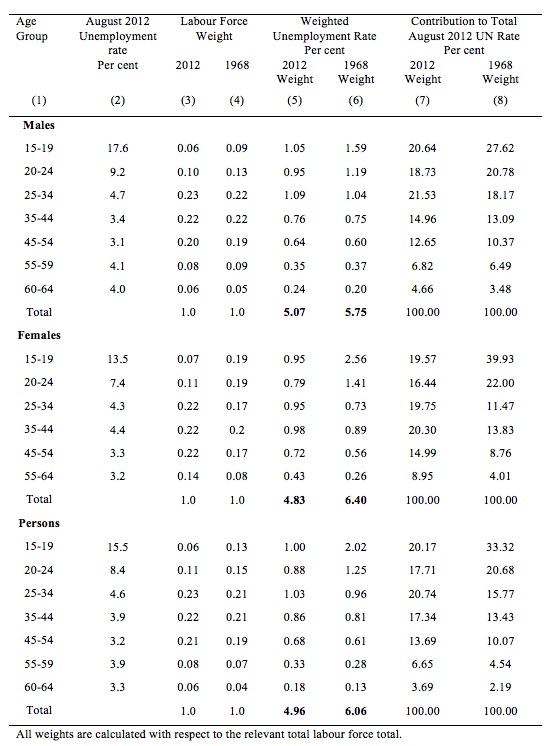

The following table is the result of my calculations. Column (2) is the specific unemployment rate for the gender-age group at at August 2012. The Persons-unemployment rate is the weighted-average of these gender-age specific rates using the August 2012 labour force weights.

Columns (3) and (4) compare the labour force weights of each gender-age cohort, relative to the relevant labour force total. So in August 1968, teenage males (15-19 year olds) constitutes about 9 per cent of the male labour force but this had declined to 6 per cent by 2012. Similarly, teenage females in 1968 we around 19 per cent of the female labour force but now constitute around 7 per cent.

This reflects the increasing participation in education over the period by younger Australians.

It also reflects the rising importance of prime-age females (25-54 years). Whereas this group comprised 54 per cent of the female labour force in 1968, they now comprise 66 per cent.

So both the ageing of the population and the social shifts in relation to female participation are reflected in the changing weights.

Columns (5) and (6) calculates the weighted-components for each of the gender-age cohorts using 2012 weights (5) and 1968 weights (6). The respective totals for males, females and Persons are the weighted average aggregates for each gender and the economy as a whole, based on the two weighting systems (2012 and 1968).

So Column (5) shows the situation as at August 2012 using the current labour force composition in terms of age and sex. Column (6) shows what the unemployment rate would have been in August 2012 if the composition of the labour force with respect to age and sex had been the same as it was in November 1968.

The difference between the two unemployment rates (for males, females and total) is due to the changing labour force composition in terms of age and gender.

Thus, if there had been no compositional shift in the labour force, then the male unemployment rate would have been higher by 0.68 percentage points, while the female rate would have been higher (by 1.6 percentage points). The aggregate (persons) rate would be 1.1 percentage points higher if the labour force composition in terms of age and sex had not changed.

Columns 7 and 8 show the changing percentage contributions of each specific age-sex group to the relevant aggregate August 2012 unemployment rate. For example, using current weights, teenage males contributed 20.6 per cent of the total male unemployment rate whereas using 1968 weights this contribution was 27.6 per cent.

The offsetting nature of the compositional changes is clearly shown. For example, the teenagers and youth in general (for persons) now contribute much less to the aggregate unemployment rate in weighted, relative terms.

On the other hand, the 25-44 prime-age group is now relatively more important in weighted terms as a consequence of the labour force changes.

Consequently, the view that compositional changes in the labour force has been responsible for a major shift in the unemployment rate is not supported by the evidence, even given the massive age and gender shifts that have occurred since the full employment era.

Conclusion

The analysis today is part of a broader project where I am creating a consistent time series to measure equivalent “labour market pressure” – that is, to generate a new full employment unemployment rate series.

Tomorrow I will write about full employment. This follows a rather extraordinary article I read this morning in the Melbourne Age which is one of the first times a journalist has bothered to address the way in which our governments have deliberately abandoned its prior (and legal) commitment to full employment.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2012 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

The BBC1 news in the UK last night was wittering on about Cameron’s failure to reduce the deficit. I nearly threw my beer can at the TV set.

Bill, please never give up repeating the point that the political left are a collection of dim-wits who can’t do anything more than ape the neo-liberal and equally dim-witted ideas emanating from the political right.

“Demand deficient unemployment occurs when the number of people wanting gainful employment exceeds the number of vacancies being offered.”

How much of all this is caused by the ‘paradox of productivity’? (as we get more productive there are less jobs available so we have to keep inventing new ones to fill the gap. And if we don’t then demand drops and it is no longer rational to create sufficient output with the new productive machine because there is a lack of income to buy it).

Clearly that paradox has been filled in by over-lending of money over recent years and that has now come to an abrupt end.

ISTM though that as we move towards a ‘Star Trek’ future where robotics does most of the producing there is going to have to be an ever greater number of jobs concocted to keep the population doing something – and that most of those are going to have to be state created (or at least state initiated).

I just can’t see a mechanism where work and the income from it is going to come about any other way (assuming we stick with a work=income=resources distribution model).

Is the debate now between those that argue that what you do to fill the day will occur spontaneously, and those that argue it will need an active agent to create something to do?

I was thinking about this today in general terms. The government’s desire is a surplus and with its aim for a surplus, they have forecast rising unemployment. Doesn’t this highlight they actually know the causal effect of a surplus in this state of an economy?

On The Age piece, I’ve always surmised that no one in Australia (and most still haven’t) have surmised what the ending of the Bretton Woods System meant in 71/officially 73. This lack of understanding that you Bill, and others have been working on for years now seems to explain why Australia at the very least has been struggling macroeconomically in the mid 70s, early 80s, late 80s and early 90s, etc. No one understands or is willing to admit that the system works differently now.

At the very least if they know they’re not willing to admit it politically. After all my initial question suggests otherwise.

Bill, Neil’s idea of the ‘paradox of productivity’ is excellent and the future does indeed look like something out of Issac Asimov. But when you read crap like that produced by Joshua Brown in The Reformed Broker – Forget Fairness, Let’s Talk Stupidity, you begin to wonder how we will ever get there. He thinks that Tony Soprano violently telling his spoiled son that he ‘doesn’t want to hear the words, ‘it isn’t fair’, again’ is the best thing he ever did for his son. Maybe it was – for his son. But to generalize this to the entire population is absurd. Should you wish to read this crap, which unfortunately many believe, here is the link.

http://www.thereformedbroker.com/2012/12/02/forget-fairness-lets-talk-about-stupidity/

The definiton of demand deficient unemployment cited by Neil above is not a good one. Reason is that given a very inefficient labour market, inflation could kick in when unemployment is much higher than vacancies. Or conversely, given a very efficient labour market, demand deficient unemployment might be where the number of unemployed is more than a quarter the number of vacancies. (The official unemployment count in Switzerland dropped to zero on two occasions in the 1960s or thereabouts.)

So my definition of DD unemployment is something like “unemployment above the level at which demand pull inflation becomes serious” – which I call NAIRU, though I realise that term is not popular hereabouts.

Re improved technology and productivity improvements, I think Neil is worrying about nothing. Those improvements have been going onfor two centuries now, but unemployment is no worse than in the 1930s or at some points in the 1800s.

When a new machine or technology is introduced which does something more cheaply than previously, that just leaves spending power in consumers’ pockets so they spend their money on something else: better houses, cars, health care or whatever. Plus some people are employed making the relevant machine / technology. There’s no need for government to come to the rescue with additional demand.

“Those improvements have been going onfor two centuries now, but unemployment is no worse than in the 1930s or at some points in the 1800s.”

And the size of the public sector?

Further discussion on any political economy topic which does not include the absolute imperative to prevent AGW (Anthropogenic Global Warming) is pointless. When severe climate change or even runaway climate change occurs there will be no modern economy (worth talking about) and eventually no people. There will be no political economy at all.

The entire world economy needs to be mobilised to one end that end being to stop AGW. This must involve the conversion to 100% renewable energy and 0% fossil fuel energy within 25 years. Anything less will not save us.

MMT (Functional Finance) has a role as dirigist mobilisation of the entire world economy to effect this changeover is mandatory if we want to survive as a species.

This existential crisis represents the ultimate proof of the maladaptive nature of corporate, oligarchic capitalism. It is a system not only of vast inhumanity and internal contradictions but also in complete contradiction to the finite nature of the biosphere and ALL ecological values (including the value of human survival).

Bill said, inter alia – ” That tells you how unsophisticated the policy debate and knowledge about economic matters is in this country. ”

Part of the problem is that the federal Treasurer is an economic illiterate. Regrettably it matters not which party is in office, because the shadow Treasurer understands even less.

Neil, I think you are assuming in your 2nd comment above that the expansion of the public sector over the last century or so has rescued us from what would otherwise have been catastrophically high unemployment levels. I don’t agree.

If we scrapped, for example, state education and health care, people would simply spend the money left in their pockets on whatever, and thus create much the same number of jobs. They’d actually spend a fair amount on education and health, just like they did in the 1800s and early 1900s. And they’d spend the rest on holidays, better housing, and so on.

Of course the most feckless ten or twenty percent would spend nothing on their children’s education or health. And that’s why we quite rightly have the state play a big role there.

“If we scrapped, for example, state education and health care, people would simply spend the money left in their pockets on whatever, and thus create much the same number of jobs. ”

Retirement pensions?

I take it from this you’re in the ‘jobs magically appear from the ether’ camp.