Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday quiz – July 21, 2012 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you understand the reasoning behind the answers. If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

The central bank sets the short-run interest rate and as part of its liquidity management functions can pay any rate on excess reserves held by the commercial banks that it chooses.

The answer is False.

The facts are as follows. First, central banks will always provide enough reserve balances to the commercial banks at a price it sets using a combination of overdraft/discounting facilities and open market operations.

Second, if the central bank didn’t provide the reserves necessary to match the growth in deposits in the commercial banking system then the payments system would grind to a halt and there would be significant hikes in the interbank rate of interest and a wedge between it and the policy (target) rate – meaning the central bank’s policy stance becomes compromised.

Third, any reserve requirements within this context while legally enforceable (via fines etc) do not constrain the commercial bank credit creation capacity. Central bank reserves (the accounts the commercial banks keep with the central bank) are not used to make loans. They only function to facilitate the payments system (apart from satisfying any reserve requirements).

Fourth, banks make loans to credit-worthy borrowers and these loans create deposits. If the commercial bank in question is unable to get the reserves necessary to meet the requirements from other sources (other banks) then the central bank has to provide them. But the process of gaining the necessary reserves is a separate and subsequent bank operation to the deposit creation (via the loan).

Fifth, if there were too many reserves in the system (relative to the banks’ desired levels to facilitate the payments system and the required reserves then competition in the interbank (overnight) market would drive the interest rate down. This competition would be driven by banks holding surplus reserves (to their requirements) trying to lend them overnight. The opposite would happen if there were too few reserves supplied by the central bank. Then the chase for overnight funds would drive rates up.

In both cases the central bank would lose control of its current policy rate as the divergence between it and the interbank rate widened. This divergence can snake between the rate that the central bank pays on excess reserves (this rate varies between countries and overtime but before the crisis was zero in Japan and the US) and the penalty rate that the central bank seeks for providing the commercial banks access to the overdraft/discount facility.

So the aim of the central bank is to issue just as many reserves that are required for the law and the banks’ own desires.

Now the question asks whether the central bank can set the short-term interest rate and the answer is clearly yes. The question also asks whether it can set whatever penalty rate that it charges for providing reserves to the banks that it likes. The answer is no because the target rate (the short-term policy rate and the support or penalty rate are closely linked – the former constraining the latter).

The wider the spread between these rates the more difficult it becomes for the central bank to ensure the quantity of reserves is appropriate for maintaining its target (policy) rate.

Where this spread is narrow, central banks “hit” their target rate each day more precisely than when the spread is wider.

So if the central bank really wanted to put the screws on commercial bank lending via increasing the penalty rate, it would have to be prepared to lift its target rate in close correspondence. In other words, its monetary policy stance becomes beholden to the discount window settings.

The best answer was false because the central bank cannot operate with wide divergences between the penalty rate and the target rate and it is likely that the former would have to rise significantly to choke private bank credit creation.

You might like to read this blog for further information:

- US federal reserve governor is part of the problem

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

Question 2:

When a currency appreciates strongly against key trading partner currencies due to the strong demand for certain exports (say mining output), the result drop in international competitiveness squeezes export industries which are not enjoying a commensurate growth in world demand. Cutting domestic wages and the rate of inflation would restore competitiveness in the industries that are under pressure.

The answer is False.

This question also applies to the EMU nations who cannot adjust their nominal exchange rate but are seeking export-led demand boosts as they cut government spending.

The temptation is to accept the dominant theme that is emerging from the public debate is telling us that wages are too high in nations that are facing a lack of export competitiveness. The fact is that deflating an economy under these circumstance does not guarantee that a nation’s competitiveness will be increased and has other undesirable outcomes.

We have to differentiate several concepts: (a) the nominal exchange rate; (b) domestic price levels; (c) unit labour costs; and (d) the real or effective exchange rate.

It is the last of these concepts that determines the “competitiveness” of a nation. This Bank of Japan explanation of the real effective exchange rate is informative.

Nominal exchange rate (e)

The nominal exchange rate (e) is the number of units of one currency that can be purchased with one unit of another currency. There are two ways in which we can quote a bi-lateral exchange rate. Consider the relationship between the $A and the $US.

- The amount of Australian currency that is necessary to purchase one unit of the US currency ($US1) can be expressed. In this case, the $US is the (one unit) reference currency and the other currency is expressed in terms of how much of it is required to buy one unit of the reference currency. So $A1.60 = $US1 means that it takes $1.60 Australian to buy one $US.

- Alternatively, e can be defined as the amount of US dollars that one unit of Australian currency will buy ($A1). In this case, the $A is the reference currency. So, in the example above, this is written as $US0.625= $A1. Thus if it takes $1.60 Australian to buy one $US, then 62.5 cents US buys one $A. (i) is just the inverse of (ii), and vice-versa.

So to understand exchange rate quotations you must know which is the reference currency. In the remaining I use the first convention so e is the amount of $A which is required to buy one unit of the foreign currency.

International competitiveness

Are Australian goods and services becoming more or less competitive with respect to goods and services produced overseas? To answer the question we need to know about:

- movements in the exchange rate, ee; and

- relative inflation rates (domestic and foreign).

Clearly within the EMU, the nominal exchange rate is fixed between nations so the changes in competitiveness all come down to the second source and here foreign means other nations within the EMU as well as nations beyond the EMU.

There are also non-price dimensions to competitiveness, including quality and reliability of supply, which are assumed to be constant.

We can define the ratio of domestic prices (P) to the rest of the world (Pw) as Pw/P.

For a nation running a flexible exchange rate, and domestic prices of goods, say in the USA and Australia remaining unchanged, a depreciation in Australia’s exchange means that our goods have become relatively cheaper than US goods. So our imports should fall and exports rise. An exchange rate appreciation has the opposite effect which is what is occurring at present.

But this option is not available to an EMU nation so the only way goods in say Greece can become cheaper relative to goods in say, Germany is for the relative price ratio (Pw/P) to change:

- If Pw is rising faster than P, then Greek goods are becoming relatively cheaper within the EMU; and

- If Pw is rising slower than P, then Greek goods are becoming relatively more expensive within the EMU.

The inverse of the relative price ratio, namely (P/Pw) measures the ratio of export prices to import prices and is known as the terms of trade.

The real exchange rate

Movements in the nominal exchange rate and the relative price level (Pw/P) need to be combined to tell us about movements in relative competitiveness. The real exchange rate captures the overall impact of these variables and is used to measure our competitiveness in international trade.

The real exchange rate (R) is defined as:

R = (e.Pw/P) (2)

where P is the domestic price level specified in $A, and Pw is the foreign price level specified in foreign currency units, say $US.

The real exchange rate is the ratio of prices of goods abroad measured in $A (ePw) to the $A prices of goods at home (P). So the real exchange rate, R adjusts the nominal exchange rate, e for the relative price levels.

For example, assume P = $A10 and Pw = $US8, and e = 1.60. In this case R = (8×1.6)/10 = 1.28. The $US8 translates into $A12.80 and the US produced goods are more expensive than those in Australia by a ratio of 1.28, ie 28%.

A rise in the real exchange rate can occur if:

- the nominal e depreciates; and/or

- Pw rises more than P, other things equal.

A rise in the real exchange rate should increase our exports and reduce our imports.

A fall in the real exchange rate can occur if:

- the nominal e appreciates; and/or

- Pw rises less than P, other things equal.

A fall in the real exchange rate should reduce our exports and increase our imports.

In the case of the EMU nation we have to consider what factors will drive Pw/P up and increase the competitive of a particular nation.

If prices are set on unit labour costs, then the way to decrease the price level relative to the rest of the world is to reduce unit labour costs faster than everywhere else.

Unit labour costs are defined as cost per unit of output and are thus ratios of wage (and other costs) to output. If labour costs are dominant (we can ignore other costs for the moment) so total labour costs are the wage rate times total employment = w.L. Real output is Y.

So unit labour costs (ULC) = w.L/Y.

L/Y is the inverse of labour productivity(LP) so ULCs can be expressed as the w/(Y/L) = w/LP.

So if the rate of growth in wages is faster than labour productivity growth then ULCs rise and vice-versa. So one way of cutting ULCs is to cut wage levels which is what the austerity programs in the EMU nations (Ireland, Greece, Portugal etc) are attempting to do.

But LP is not constant. If morale falls, sabotage rises, absenteeism rises and overall investment falls in reaction to the extended period of recession and wage cuts then productivity is likely to fall as well. Thus there is no guarantee that ULCs will fall by any significant amount.

Further, the reduction in nominal wage levels threatens the contractual viability of workers (with mortgages etc). It is likely that the cuts in wages would have to be so severe that widespread mortgage defaults etc would result. The instability that this would lead to makes the final outcome uncertain.

The answer is false because domestic deflation does not guarantee an increase in competitiveness.

You might like to read this blog for further information:

Question 3:

Aggregate demand is the sum of all spending components (consumption, investment, government spending, and net exports). In a stock-flow consistent macroeconomics, we know that flows during a period add to relevant stocks. For example, if the flow of consumption spending rose by $200 billion in total in any one year, then if nothing else changes the stock of aggregate demand would rise by the same amount in the first instance (before the multiplier starts to work).

The answer is False.

Spending definitely equals income but that is not the point of the question, which is, in fact, a very easy test of the difference between flows and stocks.

All expenditure aggregates – such as government spending and investment spending are flows. They add up to total expenditure or aggregate demand which is also a flow rather than a stock. Aggregate demand (a flow) in any period and it jointly determines the flow of income and output in the same period (that is, GDP) (in partnership with aggregate supply).

So while flows can add to stock – for example, the flow of saving adds to wealth or the flow of investment adds to the stock of capital – flows can also be added together to form a “larger” flow.

For example, if you wanted to work out annual GDP from the quarterly national accounts you would sum the individual quarterly observations for the 12-month period of interest. Conversely, employment is a stock so if you wanted to create an annual employment time series you would average the individual quarterly observations for the 12-month period of interest.

The following blog may be of further interest to you:

Question 4:

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) demonstrates that mass unemployment arises from deficient aggregate demand which calls for an increase in the budget deficit to correct the deficiency. This observation is at odds with a policy prescription which aims to cut real wages relative to productivity.

The answer is False.

In this blog – What causes mass unemployment? – I outline the way aggregate demand failures causes of mass unemployment and use a simple two person economy to demonstrate the point.

I also presented the famous Keynes versus the Classics debate about the role of real wage cuts in stimulating employment that was well rehearsed during the Great Depression.

The debate was multi-dimensioned but the role of wage flexibility was a key aspect. In the classical model of employment determination, which remains the basis of mainstream textbook analysis, cuts in the nominal wage will increase employment because it is considered they will reduce the real wage.

The mainstream textbook model assumes that economies produce under the constraint of the so-called diminishing marginal product of labour. So adding an extra worker will reduce productivity because they assume the available capital that workers get to use is fixed in the short-run.

This assertion which does not stack up in the real world, yields the downward sloping marginal product of labour (the contribution of the last worker to production) relationship in the textbook model. Then profit maximising firms set the marginal product equal to the real wage to determine their employment decisions.

They do this because the marginal product is what the last worker produces (at the margin) and the real wage is what the worker costs in real terms to hire.

So when they have screwed the last bit of production out of the last worker hired and it equals the real wage, they have thus made “real gains” on all previous workers employed and cannot do any better – hence, they are said to have maximised profits.

Labour demand is thus inversely related to the real wage. As the real wage rises, employment falls in this model because the marginal product falls with employment.

The simplest version is that labour supply in the mainstream model (and complex versions don’t add anything anyway) says that households equate the marginal disutility of work (the slope of the labour supply function) with the real wage (indicating the opportunity cost of leisure) to determine their utility maximising labour supply.

So in English, it is assumed that workers hate work and but like leisure (non-work). They will only go to work to get an income and the higher the real wage the more work they will supply because for each hour of labour supplied their prospective income is higher. Again, this conception is arbitrary and not consistent with countless empirical studies which show the total labour supply is more or less invariant to movements in the real wage.

Other more complex variations of the mainstream model depict labour supply functions with both non-zero real wage elasticities and, consistent with recent real business cycle analysis, sensitivity to the real interest rate. All ridiculous. Ignore them!

In the mainstream model, labour market clearing – that is when all firms who want to hire someone can find a worker to hire and all workers who want to work can find sufficient work – requires that the real wage equals the marginal product of labour. The real wage will change to ensure that this is maintained at all times thus providing the classical model with continuous full employment. So anything that prevents this from happening (government regulations) will create unemployment.

If a worker is “unemployed” then it must mean they desire a real wage that is excessive in relation to their productivity. The other way the mainstream characterise this is that the worker values leisure greater than income (work).

The equilibrium employment levels thus determine via the technological state of the economy (productivity function) the equilibrium (or full employment) level of aggregate supply of real output. So once all the labour markets are cleared the total level of output that is produced (determined by the productivity levels) will equal total output or GDP.

It was of particular significance for Keynes that the classical explanation for real output determination did not depend on the aggregate demand for it at all.

He argued that firms will not produce output that they do not think they will sell. So for him, total supply of GDP must be determined by aggregate demand (which he called effective demand – spending plans backed by a willingness to impart cash).

In the General Theory, Keynes questioned whether wage reductions could be readily achieved and was sceptical that, even if they could, employment would rise.

The adverse consequences for the effective demand for output were his principal concern.

So Keynes proposed the revolutionary idea (at the time) that employment was determined by effective monetary demand for output. Since there was no reason why the total demand for output would necessarily correspond to full employment, involuntary unemployment was likely.

Keynes revived Marx’s earlier works on effective demand (although he didn’t acknowledge that in his work – being anti-Marxist). What determined effective demand? There were two major elements: the consumption demand of households, and the investment demands of business.

So demand for aggregate output determined production levels which in turn determined total employment.

Keynes model reversed the classical causality in the macroeconomy. Demand determined output. Production levels then determined employment based on the current level of productivity. The labour market is then constrained by this level of employment demand. At the current money wage level, the level of unemployment (supply minus demand) is then determined. The firms will not expand employment unless the aggregate constraint is relaxed.

Keynes also argued that in a recession, the real wage might not fall because workers bargain for money or nominal wages, not real wages. The act of dropping money wages across the board would also reduce aggregate demand and prices would also fall. So there was no guarantee that real wages (the ratio of wages to prices) would therefore fall. They may rise or stay about the same.

Falling prices might, however, depress business profit expectations and so cut into demand for investment. This would actually reduce the demand for workers and prevent total employment from rising. The system interacts with itself, and an equilibrium of full employment cannot be achieved within the labour market.

Keynes also claimed that in a recession it should be clear that the problem is not that the real wage is too high, but rather that the prices are too low (as prices fall with lower production).

However, in Keynes’ analysis, attempting to cut real wages by cutting nominal wages would be resisted by the workers because they will not promote higher employment or output and also would imperil their ability to service their nominal contractual commitments (like mortgages). The argument is that workers will tolerate a fall in real wages brought about by prices rising faster than nominal wages because, within limits, they can still pay their nominal contractual obligations (by cutting back on other expenditure).

A more subtle point argued by Keynes is that wage cut resistance may be beneficial because of the distribution of income implications. If real wages fall, the share of real output claimed by the owners of capital (or non-labour fixed inputs) rises. Assuming such ownership is concentrated in a few hands, capitalists can be expected to have a higher propensity to save than the working class.

If so, aggregate saving from real output will increase and aggregate demand will fall further setting off a second round of oversupply of output and job losses.

It is also important to differentiate what happens if a firm lowers its wage level against what happens in the whole economy does the same. This relates to the so-called interdependence of demand and supply curves.

The mainstream model claims that the two sides of the market are independent so that a supply shift will not cause the demand side of the market to shift. So in this context, if a firm can lower its money wage rates it would not expect a major fall in the demand for its products because its workforce are a small proportion of total employment and their incomes are a small proportion of total demand.

If so, the firm can reduce its prices and may enjoy rising demand for its output and hence put more workers on. So the demand and supply of output are independent.

However there are solid reasons why firms will not want to behave like this. They get the reputation of being a capricious employer and will struggle to retain labour when the economy improves. Further, worker morale will fall and with it productivity. Other pathologies such as increased absenteeism etc would accompany this sort of firm behaviour.

But if the whole economy takes a wage cut, then while wage are a cost on the supply side they are an income on the demand side. So a cut in wages may reduce supply costs but also will reduce demand for output. In this case the aggregate demand and supply are interdependent and this violates the mainstream depiction.

This argument demonstrates one of the famous fallacies of composition in mainstream theory. That is, policies that might work at the micro (firm/sector) level will not generalise to work at the macroeconomic level.

There was much more to the Keynes versus the Classics debate but the general idea is as presented.

MMT integrates the insights of Keynes and others into a broader monetary framework. But the essential point is that mass unemployment is a macroeconomic phenomenon and trying to manipulate wage levels (relative to prices) will only change output and employment at the macroeconomic level if changes in demand are achieved as saving desires of the non-government sector respond.

It is highly unlikely for all the reasons noted that cutting real wages will reduce the non-government desire to save.

MMT tells us that the introduction of state money (the currency issued by the government) introduces the possibility of unemployment. There is no unemployment in non-monetary economies. As a background to this discussion you might like to read this blog – Functional finance and modern monetary theory .

MMT shows that taxation functions to promote offers from private individuals to government of goods and services in return for the necessary funds to extinguish the tax liabilities.

So taxation is a way that the government can elicit resources from the non-government sector because the latter have to get $s to pay their tax bills. Where else can they get the $s unless the government spends them on goods and services provided by the non-government sector?

A sovereign government is never revenue constrained and so taxation is not required to “finance” public spending. The mainstream economists conceive of taxation as providing revenue to the government which it requires in order to spend. In fact, the reverse is the truth.

Government spending provides revenue to the non-government sector which then allows them to extinguish their taxation liabilities. So the funds necessary to pay the tax liabilities are provided to the non-government sector by government spending.

It follows that the imposition of the taxation liability creates a demand for the government currency in the non-government sector which allows the government to pursue its economic and social policy program.

The non-government sector will seek to sell goods and services (including labour) to the government sector to get the currency (derived from the government spending) in order to extinguish its tax obligations to government as long as the tax regime is legally enforceable. Under these circumstances, the non-government sector will always accept government money because it is the means to get the $s necessary to pay the taxes due.

This insight allows us to see another dimension of taxation which is lost in mainstream economic analysis. Given that the non-government sector requires fiat currency to pay its taxation liabilities, in the first instance, the imposition of taxes (without a concomitant injection of spending) by design creates unemployment (people seeking paid work) in the non-government sector.

The unemployed or idle non-government resources can then be utilised through demand injections via government spending which amounts to a transfer of real goods and services from the non-government to the government sector.

In turn, this transfer facilitates the government’s socio-economics program. While real resources are transferred from the non-government sector in the form of goods and services that are purchased by government, the motivation to supply these resources is sourced back to the need to acquire fiat currency to extinguish the tax liabilities.

Further, while real resources are transferred, the taxation provides no additional financial capacity to the government of issue.

Conceptualising the relationship between the government and non-government sectors in this way makes it clear that it is government spending that provides the paid work which eliminates the unemployment created by the taxes.

So it is now possible to see why mass unemployment arises. It is the introduction of State Money (defined as government taxing and spending) into a non-monetary economy that raises the spectre of involuntary unemployment.

As a matter of accounting, for aggregate output to be sold, total spending must equal the total income generated in production (whether actual income generated in production is fully spent or not in each period).

Involuntary unemployment is idle labour offered for sale with no buyers at current prices (wages). Unemployment occurs when the private sector, in aggregate, desires to earn the monetary unit of account through the offer of labour but doesn’t desire to spend all it earns, other things equal.

As a result, involuntary inventory accumulation among sellers of goods and services translates into decreased output and employment.

In this situation, nominal (or real) wage cuts per se do not clear the labour market, unless those cuts somehow eliminate the private sector desire to net save, and thereby increase spending.

So we are now seeing that at a macroeconomic level, manipulating wage levels (or rates of growth) would not seem to be an effective strategy to solve mass unemployment.

MMT then concludes that mass unemployment occurs when net government spending is too low.

To recap: The purpose of State Money is to facilitate the movement of real goods and services from the non-government (largely private) sector to the government (public) domain.

Government achieves this transfer by first levying a tax, which creates a notional demand for its currency of issue.

To obtain funds needed to pay taxes and net save, non-government agents offer real goods and services for sale in exchange for the needed units of the currency. This includes, of-course, the offer of labour by the unemployed.

The obvious conclusion is that unemployment occurs when net government spending is too low to accommodate the need to pay taxes and the desire to net save.

This analysis also sets the limits on government spending. It is clear that government spending has to be sufficient to allow taxes to be paid. In addition, net government spending is required to meet the private desire to save (accumulate net financial assets).

It is also clear that if the Government doesn’t spend enough to cover taxes and the non-government sector’s desire to save the manifestation of this deficiency will be unemployment.

Keynesians have used the term demand-deficient unemployment. In MMT, the basis of this deficiency is at all times inadequate net government spending, given the private spending (saving) decisions in force at any particular time.

Shift in private spending certainly lead to job losses but the persistent of these job losses is all down to inadequate net government spending.

But in terms of the question – after all that – it is clear that excessive real wages could impinge on the rate of profit that the capitalists desired and if they translate that into a cut back in investment then aggregate demand might fall. Note: this explanation has nothing to do with the standard mainstream textbook explanation. It is totally consistent with MMT and the Keynesian story – output and employment is determined by aggregate demand and anything that impacts adversely on the latter will undermine employment.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Functional finance and modern monetary theory

- What causes mass unemployment?

- Modern monetary theory in an open economy

- Deficit spending 101 – Part 1

- Deficit spending 101 – Part 2

- Deficit spending 101 – Part 3

Premium Question 5:

If the nation is running a current account deficit of 2 per cent of GDP and the government runs a surplus equal to 2 per cent of GDP, then we know that at the current level of GDP, the private domestic sector is not saving.

The answer is True.

First, you need to understand what the aggregates mean. The statement that a government deficit (surplus) is equal to a non-government surplus (deficit) is correct to the last cent because is merely an accounting statement reflecting the way in which the national accounts are derived.

In other words, is true by definition. However, that statement tells you nothing as it stands about what, say, households are doing with respect to the use of disposable income.

Macroeconomics is the study of behaviour and outcomes at the aggregate level, and in that sense, blurs a lot of detail about what is happening below the aggregate level.

The point? It is sometimes useful to decompose the non-government sector into the private domestic sector and the external sector.

In turn, the private domestic sector is typically disaggregated in macroeconomics textbooks into the household and firm sub-sectors. From behavioural perspective, households consume and save (these are flows) while business firms produce and invest (also flows).

This is a question about the sectoral balances – the government budget balance, the external balance and the private domestic balance – that have to always add to zero because they are derived as an accounting identity from the national accounts.

To refresh your memory the balances are derived as follows. The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Equating these two perspectives we get:

C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I – S) + (G – T) + (X – M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

- The private domestic balance (I – S) – positive if in deficit, negative if in surplus.

- The Budget Deficit (G – T) – negative if in surplus, positive if in deficit.

- The Current Account balance (X – M) – positive if in surplus, negative if in deficit.

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn’t alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

A simplification is to add (I – S) + (X – M) and call it the non-government sector. Then you get the basic result that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (absolutely or as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances).

This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts and has to apply at all times.

It is clear that if we had a balanced budget (G = T) and an external balance (X = M) then (S – I) = 0.

Does this mean that there is a zero flow of saving in the economy? Definitely not. Households could still be consuming less than their disposable income which means that S > 0. What it means is that the private domestic sector overall is not saving because it is spending as much as it earns.

Clearly, if households do not consume all their disposable income each period then they are generating a flow of saving. This is quite a different concept to the notion of the private domestic sector (which is the sum of households and firms) saving overall. The latter concept (saving overall) refers to whether the private domestic sector is spending more than it is earning, rather than just the household sector as part of that aggregate.

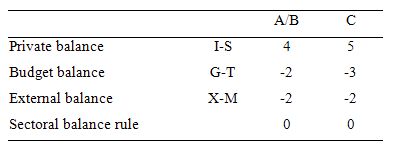

The following Table represents three options in percent of GDP terms. To aid interpretation remember that (I-S) > 0 means that the private domestic sector is spending more than they are earning; that (G-T) < 0 means that the government is running a surplus because T > G; and (X-M) < 0 means the external position is in deficit because imports are greater than exports.

The first two possibilities we might call A and B:

A: A nation can run a current account deficit with an offsetting government sector surplus, while the private domestic sector is spending less than they are earn

B: A nation can run a current account deficit with an offsetting government sector surplus, while the private domestic sector is spending more than they are earning.

So Option A says the private domestic sector is saving overall, whereas Option B say the private domestic sector is dis-saving (and going into increasing indebtedness). These options are captured in the first column of the Table. So the arithmetic example depicts an external sector deficit of 2 per cent of GDP and an offsetting budget surplus of 2 per cent of GDP.

You can see that the private sector balance is positive (that is, the sector is spending more than they are earning – Investment is greater than Saving – and has to be equal to 4 per cent of GDP.

Given that the only proposition that can be true is:

B: A nation can run a current account deficit with an offsetting government sector surplus, while the private domestic sector is spending more than they are earning.

Column 2 in the Table captures Option C:

C: A nation can run a current account deficit with a government sector surplus that is larger, while the private domestic sector is spending more than they are earning.

So the current account deficit is equal to 2 per cent of GDP while the surplus is now larger at 3 per cent of GDP. You can see that the private domestic deficit rises to 5 per cent of GDP to satisfy the accounting rule that the balances sum to zero.

The Table data also shows the rule that the sectoral balances add to zero because they are an accounting identity is satisfied in both cases.

So what is the economic rationale for this result?

If the nation is running an external deficit it means that the contribution to aggregate demand from the external sector is negative – that is net drain of spending – dragging output down.

The external deficit also means that foreigners are increasing financial claims denominated in the local currency. Given that exports represent a real costs and imports a real benefit, the motivation for a nation running a net exports surplus (the exporting nation in this case) must be to accumulate financial claims (assets) denominated in the currency of the nation running the external deficit.

A fiscal surplus also means the government is spending less than it is “earning” and that puts a drag on aggregate demand and constrains the ability of the economy to grow.

In these circumstances, for income to be stable, the private domestic sector has to spend more than they earn.

You can see this by going back to the aggregate demand relations above. For those who like simple algebra we can manipulate the aggregate demand model to see this more clearly.

Y = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that the total national income (Y or GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

So if the G is spending less than it is “earning” and the external sector is adding less income (X) than it is absorbing spending (M), then the other spending components must be greater than total income

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

Q3: “Spending definitely equals income but that is not the point of the question”

From another post (Some notes on Aggregate Supply Part 2): “However, this is where the existence of credit money is relevant. The money supply is endogenous and highly responsive to the demand for credit by the non-government sector.”

Can there be any “problems” with those two(2) phrases getting along?

Q4: Why can’t mass unemployment arise because the number of people in retirement is not high enough?

“MMT tells us that the introduction of state money (the currency issued by the government) introduces the possibility of unemployment. There is no unemployment in non-monetary economies.”

So does that bring up the possibility that there is something wrong in the medium of exchange “market” (not money because there are too many definitions). If so, can that affect the retirement market?

Q5: “GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)”

Does it matter what time period your C, I, G, and (X-M) are coming from?

On question 5. Does the current account balance always equal X-M , and if not could that possibly change the answer to your question. I ask because I was sure this was some kind of trick question (since you called it the ‘premium’ question) and changed my answer. Obviously got it wrong at that point. Maybe these quizzes are making me paranoid

I am a bit confused on Q1. The questions says “and as part of its liquidity management functions can pay any rate on excess reserves” but the answer says “The question also asks whether it can set whatever penalty rate that it charges for providing reserves”. Paying and charging are not the same thing are they?