I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Inflexible governments undermine our standards of living

I keep reading news reports that claim that Apple (the company) has more cash to spend than the US government. For example, this ABC News report today (March 20, 2012) – Apple goes on massive spending spree – perpetuates this myth. I noticed a similar report was spread throughout the Internet overnight. Apple might have 90 odd billion US dollars in cash reserves at present which it could draw on at its leisure. But once its reserves were gone that would be it. Notwithstanding, the labyrinthine accounting arrangements, which obfuscate its true capacity, the US government could spend 90 billion tomorrow, 90 the next day, and 90 the day after that if it wanted to. I am not advocating that just noting the capacity. This example highlights how poorly we are served by the financial press which reinforces the ideologically-motivated lies the government’s and the corporate elites use to maintain their hegemony. Inflexible governments undermine our standards of living.

Today (March 20, 2012), the RBA released its Minutes of the Monetary Policy Meeting of the Reserve Bank Board today (for its March 6, 2012 meeting) – and explain why they held the target policy rate constant at 4.25 per cent, which is of-course high by current world standards and not a small reason why the exchange rate is so strong at present.

Essentially, the RBA thinks the Euro crisis is abating (my prediction is that they will be proven wrong on this front), China will continue to growth at a “more sustainable pace” (implying that the Chinese government has inflation under control), and that the “US economy had emerged from its soft patch in mid 2011”.

The RBA noted that our “terms of trade had declined from their peak in the September quarter … but remained at historically high levels” and that the Australian economy was subject to “divergent conditions across sectors” with “strong investment in mining-related sectors” but subdued prospects for the other export sectors hit by the high Australian dollar.

They said that “(r)etail sales growth had softened since mid 2011” and the “housing market remained soft”.

The data coming from the labour market was evidence of the dual nature of economic growth in Australia at present. The latest ABS data – Labour Force, Australia, Detailed, Quarterly, Feb 2012 – shows that over the last 12 months total employment in the most populated East coast states (Victoria and New South Wales) has declined by 1 per cent overall, whereas employment in the mining states (Queensland and Western Australia) has grown by 2.2 per cent over the same period.

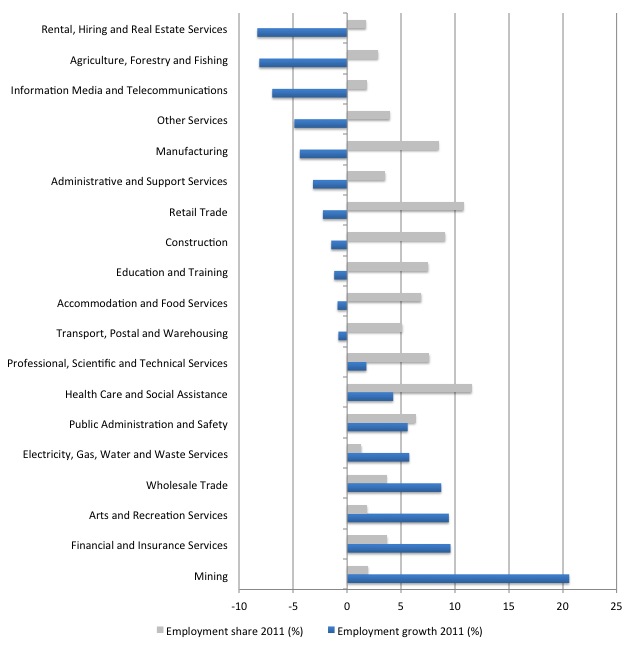

The following graph shows employment growth by the ANZSIC (one-digit) industry sectors for 2011 (per cent) ordered worst to best (blue bars) and the share of each sector (2011) in total employment (grey bars).

Total employment growth was for the entire economy was close to zero. The graph provides you with a sense of the staggering differences in outcomes across the industry structure last year.

If I was to graph the outcomes by State (region) we would find that the losing industries dominate in Victoria, NSW, South Australia and Tasmania (South Eastern part of Australia) and the Mining industries are dominant in the Western and Northern part of the nation where relatively few people live.

The dichotomous nature of Australian economic fortunes at present is significant. Mining grew by 20 per cent, although it remains a very small employer (2 per cent of total). The large employers of Australian workers are dominated by those going backwards.

The RBA Minutes state:

… the domestic economy continued to undergo significant structural adjustment in response to the very high terms of trade and the accompanying high exchange rate. A key question was whether the necessary adjustment was occurring at an overall pace of growth that kept the economy close to trend and inflation close to target. In this regard, most information thus far had indicated that weakness in parts of the economy – including manufacturing, building construction and parts of the retail sector – was being approximately balanced by the strength in the mining sector and some services industries.

Which is code for the RBA’s view that it has to maintain contractionary interest rate positions to provide space for the mining sector to grow without inflation. I will come back to this theme soon.

Yesterday, (March 19, 2012), the Sydney Morning Herald economics editor Ross Gittins article – How both sides wrecked the tax base – focused on fiscal policy in relation to the present situation in Australia.

Ross Gittins notes that “since the global financial crisis, federal tax revenue had fallen by the equivalent of 4 percentage points of gross domestic product [about $60 billion a year]” and that this has:

… made the task of maintaining medium-term budgetary sustainability harder for both the Commonwealth and the states …

He was referring to comments made by the new Treasury Secretary last week that suggested that there is “now a disconnect in the established relationship between the rate of growth in the economy and the rate of growth in tax collections. The economy can be growing at a reasonable rate without that meaning tax collections are growing strongly.”

I considered the Treasury Secretary’s comments in this blog – Keynes would not support fiscal austerity.

Ross Gittins concludes that the result is that:

It will be a lot harder in future for politicians of either side to keep the budget in surplus.

You will note he doesn’t challenge the wisdom of keeping the “budget in surplus”. The reality is that the recent history is not a reliable guide to what is normal.

The Australian government, for example, was only able to run surpluses for 10 years out of 11 (1996-2007) because private credit growth was so strong. This was a characteristic of the neo-liberal period.

Before the neo-liberal era, we witnessed:

1. Relatively continuous use of fiscal deficits.

2. Stable personal saving ratio of around 7-8 per cent of personal disposable income.

3. A consumption share of around 65 per cent of GDP.

4. Real wages growing in line with labour productivity – so that consumption could be driven by real wages growth rather than credit.

The neo-liberal period is in fact the outlier – an atypical period. Which makes the claims by those who hold out that governments should return to surplus as a demonstration of fiscal responsibility rather difficult to understand.

During the neo-liberal period, where actual budget surpluses were recorded, the economies typically went into recession soon after. The important point though is that the surpluses were made possible by the unsustainable growth in private credit which drove private spending and boosted tax revenue.

So it is highly likely that we are returning to a more normal environment now where the private sector are attempting to save more out of disposable income and reduce its reliance on credit.

Two implications arise if that if the private consumption is returning to more normal levels then two things follow:

1. The government will more likely have to run budget deficits of some magnitude indefinitely – as in the past.

2. Real wages growth will have to be more closely aligned with productivity growth to break the reliance on credit growth.

And when the nature of the balance sheet adjustments that are going on at present are included in the assessment these two points become amplified.

So waiting for a private consumption boom to save the economy is probably going to be a long wait. But it is also a trend that we don’t want to see revived under the previous circumstances – noted above.

This also makes the quest for fiscal austerity to be mindless and very destructive. Where will growth ever come from if consumers are returning to higher saving ratios, firms are very cautious, all countries are eroding each other’s export markets, and governments are adding tot he malaise?

Please read my blog – Budget deficits are part of “new” normal private sector behaviour – for more discussion on this point.

Juxtapose Gittin’s view with that expressed in today’s (March 20, 2012) Melbourne Age column (also a Fairfax publication) – Our facts have changed – by its economics editor, Tim Colebatch.

He argues that “Governments are showing no flexibility despite Australia’s unprecedented situation” and that situation is “unlike anything we have seen before. In the year to December 2011, investment in mining grew by more than GDP did. Mining investment grew by $8.24 billion; the volume of GDP grew by only $7.7 billion”.

I have been asked a lot by journalists about this question since the national accounts data came out a few weeks ago. I have done work in the past on mobility patterns of the workforce, especially in times of reduced economic growth. Our research shows that while there is some mobility between low growth and higher growth regions, such mobility tends to be concentrated among the higher skilled workers.

We have found evidence of what is known as the “bumping down” effect, whereby in an environment of an overall job shortage, higher skilled workers move to areas where employment growth is positive and out-compete local lower skilled workers for jobs that the latter group would normally take.

So, mobility combined with an overall job shortage sees higher skilled workers bumping out lower skilled workers from their normal opportunities.

These mobility patterns are not strong enough to resolve disparate labour market circumstances across space. The mainstream economics belief that relative wage movements would also lead to a resolution of supply of and demand for labour imbalances is also empirically false.

The other important point to note is that such mobility tends to occur between regions with similar characteristics (for example, public infrastructure, social networks etc).

Mobility is still quite restricted by housing, family and social network issues.

What we are now seeing is very little mobility because of housing affordability issues and a lack of proximate job opportunities.

Moreover, there is virtually 0 mobility between the populated East Coast regions (where employment growth is weak or negative) and the remote, sparsely populated mining areas in the North and north-west of the country.

This is highly significant because it undermines the entire strategy that the central bank and the Treasury are imposing on the country to the detriment of the vast majority of the population and the significant employing industries that are concentrated in the eastern states.

This is a point that Tim Colebatch also reflects upon. He says:

One industry located mostly in the outback is growing very fast. Most of the rest of the economy, located in the south-eastern cities, where the bulk of Australians live, is growing slowly or not at all.

He lists three main reasons for this dichotomy aand why “our economy has hit a wall”.

1. “the Australian dollar has risen to hover around $US1.05 – 50 per cent above its long-term average of US70¢. This has made a wide range of economic activity uncompetitive, forced firms to close and sent tens of thousands of jobs overseas”.

2. The RBA “has set interest rates at levels appropriate for mining, not for the mainstream of the economy … The economy needs stimulus, yet interest rates are contractionary”.

3. “governments are cutting spending to get back to surplus, and cutting hard because revenues have been clobbered by tax losses run up in the global financial crisis, by consumers’ caution and by the lack of growth.”

As regular readers will appreciate I have been consistently arguing that the policy settings in Australia are inappropriate for our circumstances, particularly the federal government’s obsessive pursuit of the budget surplus at a time when economic growth is well below trend, unemployment is rising, broad labour underutilisation is still around 14 per cent, and the private sector is intent on tightening its belts.

There is absolutely no justification for the government to be pursuing a budget surplus at this time.

As Tim Colebatch notes:

Our facts have changed. But our governments, the Reserve Bank and the federal opposition have not changed their minds. What is happening to Australia does not fit the stories each wants to tell us. So for different reasons their policy is to ignore it, and hope that it goes away.

The Federal government is caught up in the fiscal austerity narrative that the neo-liberals had imposed on failing economies everywhere.

It thinks that if it maintains its pursuit of a budget surplus the electorate will reward it for being a responsible fiscal manager. However, the electorate is more concerned about real income growth and employment opportunities and the government’s current strategy is undermining both.

What the Government also fails to grasp is that in trying to achieve a budget surplus at a time when the economy is slowing that the automatic stabilisers (that is, the plunging tax revenue growth) will likely see the budget in deficit anyway and nothing positive to show for it.

Pro-cyclical fiscal policy at a time when private spending is weak overall is very irresponsible fiscal management.

Tim Colebatch notes that the current (inflexible) policy response (by our central bank and treasury) is:

… to allow Australian manufacturing and service industries to wither, hoping this will “free up” workers to take jobs in mining without causing inflation.

This is not good enough. Our manufacturers are constantly berated with advice that they must be flexible and nimble in responding to challenges. So they do; but it is ludicrous when the advice comes from those who are inflexible in their own job: policy.

As noted above, the strategy, at minimum, requires substantial mobility of labour resources from the East Coast where most people live to the remote north and north-west parts of our continent, where there is very little other than beautiful natural landscapes, deserts, and holes in the ground (aka mines).

The evidence is that this mobility is not occur – and more emphatically, will not occur. People will not move to these remote areas where there is a paucity of social infrastructure including schools and hospitals and other essential characteristics of a sophisticated lifestyle in an offence nation.

Tim Colebatch argues that nations such as Switzerland drew “a line in the sand” and:

…. intervened in the market to force the franc back below 1.20 to the euro, and keep it there. Central banks can do this because they can create currency.

They did this to protect their manufacturing sector as the franc appreciated relative to its major trading partners.

In Australia, we simply hope the “market” will deliver some serendipitous outcomes despite the evidence that this never happens.

Tim Colebatch says that:

We need to talk too about why Canberra is pledging a budget surplus that will impose a contractionary budget on an already weak economy.

It is obvious that the federal government (that is, for overseas readers “Canberra”) needs to be supporting growth via a budget deficit.

The journalist asked me today how I would approach this dichotomous growth outlook. The point I made was that deliberately starving the sectors that employ the most Australians of demand (via high interest rates and fiscal drag) is an absurd policy stance for a government to take.

There is some presumption that the mining sector should grow as far as the demand for resources will take it, even though it is clear that the majority of Australians are not enjoying the benefits of that growth.

I made the point that if the overall economy was growing strongly we would have no hesitation in putting on the policy brakes to avoid an inflationary spiral of emerging. The solution would seem obvious – the Australian government, if it really believes that labour shortages in the mining sector are going to drive widespread wage inflation in Australia (I do not believe that, can simply introduce policy initiatives that will reduce the growth of mining.

At the same time it should be maintaining its stimulus for the rest of the economy, which not only employs the overwhelming majority of workers are also produces the overwhelming majority of our national income.

The beauty of fiscal policy (as opposed to monetary policy) is that specific sectors can be targetted for stimulus or contraction while maintain the opposite overall policy stance. If there are inflationary bubbles emerging in one sector – for example, real estate – then targetted taxation initiatives are appropriate and very effective.

Using a broad (blunt) instrument like the overall interest rate to target specific sectors is poor policy and largely ineffective (given the vagaries about the direction of monetary policy impact and its timing).

I noted that yesterday that the government finally had its new mining tax passed by the Australian Senate and it will become law later this year. The problem is that the watered-down proposal that was finally agreed when the federal government succumbed to the public advertising campaign mounted by the mining industry in opposition to the tax is pathetic.

Relative to international attempts to ensure that mining companies pay a reasonable rental on resources that we all own, the government’s tax is pathetic.

If the mining sector has to be slowed down then the mining tax should be higher. I will consider the mining tax in a separate blog some time in the future.

Conclusion

It is about time that some of the mainstream journalists in our large daily newspapers start taking the government to task about its absurd policy position.

We will rue the day when the larger employers fail because we kow-towed to the mining sector – which is a relatively small contributor to our overall living standards.

Inflexible governments undermine our standards of living. The art of fiscal policy management is to ensure the policy settings adjust to the challenges that are faced. Governments that blindly follow fiscal rules or mantras (such as, “surplus at all costs”) are demonstrating their incompetence.

There is a time for contractionary fiscal policy but only when the circumstances permit and the strategy enhances living standards not undermines them. Our government, like most, is acting contrary to our best interests because it has been captured by neo-liberalism, which constructs fiscal policy as an evil.

That is enough of the day!

Bill,

My reading is that its worse than you think. It looks like Commodities Supercycle Part Deux is coming to an end:

http://ftalphaville.ft.com/blog/2012/03/20/929711/the-supercycle-is-so-over-iron-ore-edition/

China is switching from investment-led growth to consumption-led growth. So, the current mining boom in Australia is going to be smothered in its crib. How the Oz government don’t recognise this is literally shocking. But as we all know, sometimes its easier to believe something you want to believe because it fits your narrative despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

Also, although this is harder to tell, I reckon that Randy Wray is right about speculation in the commodities markets. Although I think most of it is taking place through hoarding rather than typical financial speculation:

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-03-13/goldman-says-china-may-have-500-000-tons-of-copper-in-warehouses.html

If Chinese demand starts to contract these hoards could flow out of stockpiles and blow the lid off the commodities market. If that happens the Aussie mining sector can say good night!

Hope for your guys sake that I’m wrong…

Phil

Apple has neither more nor less cash than the US government to spend.

Bill,

As usual, a great post. I have two questions / comments

1. MMT teaches us taxes do not “fund” spending, but act to regulate demand. I believe some MMTers think this allows for substantially lower company taxes since companies Invest rather than consume. With that in mind, can it be argued the mining tax is a bit of a non-event.

2. You suggest neo-liberal fiscal surpluses were a consequence of a “credit binge”. If that was the case, why didn’t the credit binge in the US result in a surplus? Could it not be argued in reverse, that Australian credit growth was the result of the surplus?

I’m not an official MMT person – However.

1. Taxes create demand for the governments otherwise worthless fiat money because it is the only acceptable unit by which the non-government sector can meet tax obligations.

The idea that it regulates demand is more in line with neo-liberalism. MMT would suggest that taxes transfer goods and services from the private sphere to the public sphere.

2.Government surplus = non-government sector deficit.

Non-government sector is forced to resort to credit once it’s saving / bond holdings have been eroded.

Hence, government surpluses lead to increases in credit spending by the non-government sector if they desire to maintain or increase their standard of living (so to speak).

Chris you seem to be betting each-way here. I think Clintons surplus started the credit growth ball rolling in the USA.

In Australia, Howard / Costello were the culprits.

Banks love these blokes .

cheers.

Hi Alan

1. I think you are suggesting taxes “make room” for governments to claim additional real resources in a non-inflationary manner (ie: minimise crowding out). I accept this point – but only to the extent mining profits are used in the mis-allocation or consumption of, real resources. Perhaps Bill will elaborate in future posts.

2. Not sure how I am having an each-way bet. It seems to me Bill’s view is the budget surplus was a consequence of private credit growth, rather than the other way around.

When you think about the Howard / Costello years and to a lesser extent Hawke / Keating years, Australia had fully embraced the neo-liberal concept of user-pays. We have seen this with numerous infrastructure projects and privatizations since about 1990. You can not drive around Sydney for more than 10 minutes without incurring about $20 of road tolls!!!

Surely there is a case to say the governments pursuit of user pays has reduced the “burden” of federal funded projects and shifted them to the private sector – reducing Federal deficits and leading to higher private debt.

Nb: The Clinton surpluses ended in 1999-2000. http://www.usgovernmentspending.com/include/usgs_chart4p04.png

Yet the private credit binge in the US really accelerated AFTER this point while Bush ran deficits.

http://www.skeptically.org/sitebuildercontent/sitebuilderpictures/us-private-debt-to-gdp-20-09.jpg

Chris.

The BOOT (Build Own Operate Transfer) schemes I think you are talking about were / are state government policy not so much federal.

How can any burden be reduced for a federal government via user pays ?

State governmetns perhaps – Federal governments though are not constrained in terms of their own money.

Clinton years ? Lags.

Hi Alan

Please do not get me wrong – i know there is no “financial burden” for a fiat issuing federal government.

To re-phrase my assertion “Surely there is a case to say the governments pursuit of user pays reduces Federal deficits and leading to higher private debt”.

And yes – many of these “BOOT” schemes were State inspired – but by balancing state budgets via these schemes, the Federal Governments provided less “fiscal transfers” via Federal appropriations – so there is a direct relationship between “BOOT” schemes, and lower Federal deficits (higher surpluses).

Clinton years Lags? What do you mean? It is pretty straight forward Isn’t it? From 2001-2006 private credit growth exploded in the US, but they ran Federal deficits? Why is Australia so different?

Hi Bill ,why does Australia need to be a part of OPEC when we have such large oil reserves. I would like to see Australia use its own oil supply /creates jobs and we shouldnt be subject to overseas fluctuations and high prices. (my kids havent forgotten Nobbys beach and break fast afterwoods ) Bye for now and take care ,Paul Mc

credit card rate caps were removed in the 1990’s. dogs and babies had mailboxes stuffed with pre-approved 30% cards. mortgages were collateralized credit sold on commission following the same model. all revenue streams were bundled and sold to muppets with dumb money, like hbos and rbs. broker dealers were two years advanced on the asymmetric information highway relative to dumb money but the velocity of the system was too great to control. inflation can be velocity driven hence the reason for a transaction tax. negative interest rates wants an issue of stamp money or a fiscal equivalent to increase velocity. bubbles are a velocity problem.