I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Budget deficits are part of “new” normal private sector behaviour

Today I am in the nation’s capital, Canberra presenting a class at the European Studies Summer School which is being organised by the Centre for European Studies at the Australian National University. My presentation is entitled – the Euro crisis: fact and fiction. I will have more to say about that in another blog. Today I am considering the issues surrounding the decline in personal consumption spending and increased household saving ratios. The argument is that this behaviour which is now clearly evident in most economies marks an end to the credit-led spending binge that characterised the pre-crisis period of the neo-liberal era. But with that era coming to an end and more typical (“normal”) behaviour emerging, the way we think about the government (as the currency-issuer) will also have to change. There is clearly resistance to that part of the story, in part, because there is a limited understanding to the central role that the government plays in the monetary system. As private sectors become more cautious, we will required continuous budget deficits to become a part of this return to the “new” normal.

There were two competing articles in the Australian press today – Fight the slump with a wide-open wallet – by Yale economist Robert J. Shiller and Brace for pain at passing of the old order by Australian economist David Llewellyn-Smith.

I disagree with the main thrust of both articles although they are very interesting in their own way.

Robert Shiller’s article (January 17, 2012) argued that with the US political process in “gridlock” which “implies that there will not be any collective decision to spend more as a nation to get the United States out of its slump”, the US:

… must pin … [their] … hopes for a robust recovery on the willingness of millions of consumers to spend substantially more.

He thinks that economists “aren’t very good at predicting spending shifts”. Which begs the question – why not wait for them to manifest and in the meantime maintain fiscal support for aggregate demand.

This strategy also has the consequence of providing the conditions for the private sector to regain confidence.

Mass unemployment is a sure sign that the budget deficit is too low given the current private spending and saving decisions.

His article is aimed at sharing the insights into a new book – Beyond Our Means: Why America Spends While the World Saves – which he says provides “some insights” into why consumers are currently not spending.

The hypothesis is that spending patterns are “driven most prominently by our reaction to major events in our collective memory, including wars and depressions, and that it also depends on national character, which differs across countries and through time”.Which is not a controversial proposition.

Moreover, in times of relative stability consumer spending patterns also exhibit stability. One of the essential conditions for stability is that private balance sheets are sustainable which is tantamount to saying that consumption growth is driven by real wages growth which is proportional to productivity growth.

In the neo-liberal (last 25-30 years) this pattern was interrupted as governments attacked the capacity of workers to secure real wages growth in line with the growth in productivity. The massive redistribution of national income towards profits that has been characteristics of the neo-liberal period to date has provided evidence of that.

This real income grab provided the resources for the financial sector which allowed it to grow so spectacularly. It also meant that consumption growth had to be “funded” via the acceleration of credit which over time led to the deterioration in private balance sheets and, ultimately, the financial collapse.

Robert Shiller says that the above-mentioned book considers the US “is an exception” because:

More than any other country … it elevates consumer spending to a virtue, sometimes minimising saving. There is even an idea here that it is patriotic to spend, rather than to save.

He cites the post-September 11 2001 appeal by the then president for Americans to “Get down to Disney World in Florida” and spend up – as evidence that consumption spending can stimulate growth and push an economy out of recession.

His point is that confidence is a key to spending. He believes that confidence is currently lacking as a result of all the talk about doom.

Expectations and confidence are slippery concepts for economists who want to reduce everything to optimising calculus (the main tools of mainstream economics).

We know that when there is unemployment and falling income, private confidence will be low and subdued spending behaviour will follow. Firms will not invest until they are sure that they can sell the extra output that would be produced by the new productive infrastructure.

Consumers will not provide them with those guarantees because they are worried about their job viability.

Then add the fact that this is a balance sheet recession to the mix which requires years of private deleveraging to restore the sustainability of private balance sheets.

The result – a very drawn out period of subdued private spending overall.

Under those conditions, sustained budget deficits are required to support aggregate demand growth, which in turn, helps the private sector regain confidence.

But in a period of balance sheet adjustment, private spending will remain flat because the main task is reducing debt to sustainable levels.

However, there may be more to it than that. While it is clear the households are lifting their saving ratio out of disposable income and private investment remains relative subdued, my contention is that this is part of a long-term adjustment going on back to what we might consider to be normality.

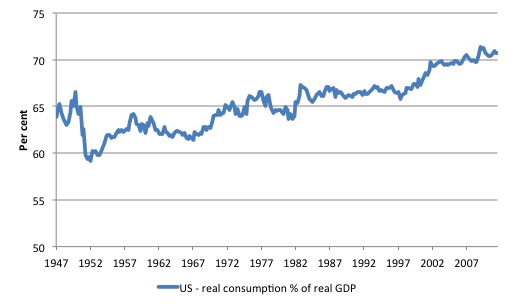

The following graphs show the two sides of the same coin. Both use the US Bureau of Economic Analysis National Accounts data.

The first graph shows the share of real personal consumption expenditure in real GDP in the US since the first-quarter 1947.

After the recovery following the Second World War occurred there was a period of relative stability. Real wages grew in proportion to labour productivity which helped fund consumption growth – although the share remain more or less constant until the 1990s.

As the wage share was being reduced by various government policy changes and other factors in the 1980s and 1990s, the growth of credit accelerated and personal consumption jumped as a share of real GDP.

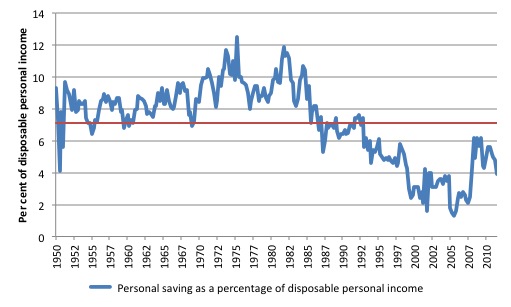

The other side of this coin, is the personal saving as a percentage of disposable personal income shown in the next graph. the red line is the sample average 7.1 per cent (from March-quarter 1947 to September-quarter 2011). If we take out the period after December-quarter 2004, the sample average rises to 7.5 per cent.

The decline of the saving ratio broadly corresponds to the rising consumption share shown in the first graph. At first, as real wages growth was being squeezed in the US, households maintained spending by reducing their saving ratio.

That trend accelerated in the latter half of the 1990s as financial market deregulation allowed the financial markets to create all sorts of “financial instruments” which were all designed to push more and more credit onto the private sector.

Clearly, the situation was unsustainable as the balance sheet risk increased.

The point is that the period before the neo-liberal era was characterised by several features.

1. Relatively continuous use of fiscal deficits.

2. Stable personal saving ratio of around 7-8 per cent of personal disposable income.

3. A consumption share of around 65 per cent of GDP.

4. Real wages growing in line with labour productivity – so that consumption could be driven by real wages growth rather than credit.

The neo-liberal period is in fact the outlier – an atypical period. Which makes the claims by those who hold out that governments should return to surplus as a demonstration of fiscal responsibility rather difficult to understand.

Please read my blog – The Great Moderation myth – for more discussion on this point.

In many cases, where actual budget surpluses were recorded, the economies went into recession soon after. The important point though is that the surpluses were made possible by the unsustainable growth in private credit which drove private spending and boosted tax revenue.

In the Eurozone, Spain and Ireland recorded budget surpluses in the lead up to the crisis and were held out as the exemplar of fiscal prudence and financial management. History has a way of showing nonsense for what it is. Their ridiculous real estate booms drove the surpluses. The surpluses, in fact, squeezed the capacity of the private sectors to maintain reasonable saving ratios – which would have ensured better private risk management.

So it is highly likely that we are returning to a more normal environment now where the private sector are attempting to save more out of disposable income and reduce its reliance on credit.

Two implications arise if that if the private consumption is returning to more normal levels then two things follow:

1. The government will more likely have to run budget deficits of some magnitude indefinitely – as in the past.

2. Real wages growth will have to be more closely aligned with productivity growth to break the reliance on credit growth.

And when the nature of the balance sheet adjustments that are going on at present are included in the assessment these two points become amplified.

So waiting for a private consumption boom to save the economy is probably going to be a long wait. But it is also a trend that we don’t want to see revived under the previous circumstances – noted above.

This also makes the quest for fiscal austerity to be mindless and very destructive. Where will growth ever come from if consumers are returning to higher saving ratios, firms are very cautious, all countries are eroding each other’s export markets, and governments are adding tot he malaise?

Answer: nowhere. That is the problem.

The second article – Brace for pain at passing of the old order – is more Australian focused and considers what the future might look like for our economy.

The author, David Llewellyn-Smith argues that:

The shift is that yesterday’s demand-driven economy, which relied upon debt to inflate assets and drive private balance sheet growth as well as consumption, has ended.

It is finished permanently (or for so long that it might as well be permanent). The global growth of the future will be driven by the forces of investment, production and intensified competition for that limited demand.

This sounds like we agree that private balance sheets are in retreat which will put a stop to the rampant consumption-binge that the world experienced in the lead up to the crisis.

He considers that the “the European “crisis” is nothing more than the latest expression of the underlying reality that countries will now need to compete successfully to grow”.

Then we depart. The European crisis is the result of the flawed design of their monetary system. They refused, from the outset, to put in place a fiscal capacity that could respond to a major negative demand shock. They took currency sovereignty away from member states and separated fiscal and monetary policy. They fixed exchange rates which meant the external imbalances could only adjust via domestic deflation.

Sure enough the private debt binge associated with (but not exclusively) to the real estate booms in various nations was tied into the crisis. That sector collapsed and governments, bound by their strange commitment to fiscal austerity, refused to stop the financial mess spreading into the real sector.

But all of that could have been more easily accommodated had the member states retained their floating currencies and enjoyed integrated central bank- treasury relationships.

The other point is that you don’t get growth without spending. That means that the “investment-led” growth competing for demand will only be supportable if there is spending.

The challenge is to re-balance the composition of final output across the spending categories rather than rely on credit-fuelled consumption spending for growth.

The author then thinks that his investment-led, tight demand “paradigm shift”:

… reframes as visionary Germany’s recalcitrant insistence that its southern peers reform their economies in return for fiscal support (even if its various tactics for achieving this end are self-defeating).

Today I mentioned in my presentation at the Euro summer school that the celebration of German prudence is a misnomer. Just as the celebration of Spanish and Irish surpluses was a misnomer. Both relied on something else happening.

In the German case, they deliberately suppressed domestic demand (by containing real wages growth well below the growth of labour productivity – via the Hartz and other reforms) as a way of maintaining external competitiveness once they had abandoned their floating exchange rate.

In the past, the Bundesbank would manage monetary policy to ensure the mark was low enough to keep the German export machine competitive.

The effect of the German government’s decisions to push through the Hartz reforms which effectively undermined the capacity of workers in Germany to enjoy appropriate real wage increases meant that not only did German “investment” have to go in search of profit opportunities but that the German economy became increasingly dependent on spending from other nations for their growth.

The suppression of consumption in Germany and the reliance on capital export to the “south” to maintain growth has been very damaging to the member states in the south. But the obvious point is that if the “southern states”, now being vilified as being profligate, hadn’t maintained their spending (and purchasing of German exports) the German economy would have falling into recession.

The two sides of the same coin: “visionary German” austerity – “lazy Greek profligacy”.

David Llewellyn-Smith also gets aboard the fiscal consolidation train claiming that his “new paradigm”:

… repositions the period of relatively stable economic growth currently enjoyed in the US as little more than an oasis of demand-driven calm before the real work begins of addressing its growing fiscal burden and ongoing credit excess.

There will be no investment boom until there is renewed aggregate demand growth. A nation cannot build up a capital goods industry forever. Capital goods generate consumer goods and services which have to be purchased.

There may well be some investment renewal based on best-practice technology which will try to compete for market share. But growth will only return when the consumer goods and/or public infrastructure spending increases.

It is clearly preferable, going on the logic outlined above, that households be supported by fiscal policy to return their balance sheets back into safe waters. That will require governments returning to their “normal” role – running budget deficits.

That is the “ongoing credit excess” in the private sector has to be reversed and that will require public net spending support.

There is no “growing fiscal burden” in the US. It might be that the political process will endorse a larger share of public resource usage over time as the population ages and health care provision needs increases.

The net burden of that trend will be the sum of the resources deployed in the health and aged care industries minus the resources freed from other areas (like primary school education, child health centres).

The US government will always be able to purchase whatever level of goods and services it deems politically appropriate as long as they are for sale in US dollars. There will be no financial burden involved.

I agree with David Llewellyn-Smith that there are major shifts afoot in world demand patterns – for example, China and India are emerging as the powerhouses and this will change energy use and have serious ramifications for Australia, the US and other nations that have been enjoying cheap energy resources for years while China and India remained poor.

Please read my blog – Be careful what we wish for … – for more discussion on this point.

But these large shifts are not going to reduce the central role that the currency issuer has to play in an economy if domestic prosperity is to be pursued.

David Llewellyn-Smith thinks that this “new era” will have many “downside risks” for nations such as Australia. He thinks that much of the “old part of the economy” (non-Mining) is moribund and that “(h)ousehold debt levels are still very elevated”.

I agree.

He says that consumers will not be resuming their credit-binged consumption growth.

As noted above, I agree with that.

This will lead firms to seek cost efficiencies and “(p)roductivity will raise its head from the canvass” with the upshot that “jobs will go”.

With the external sector riding on the back of the Chinese growth period and the services sector languishing, he expects that economic “growth will be lacklustre”.

Then he concludes:

Irrespective of growth outcomes, expect more fiscal tightening in 2012.

Why should we expect that? It will probably happen but not as an act of appropriate fiscal policy – more a stubborn act of ideological vandalism.

With lacklustre growth and the East Coast economy (non-mining, and most populated) in near recession we should be demanding our government increase its fiscal support for the private sector deleveraging.

The obsessive pursuit of budget surpluses, even though that pursuit will be self-defeating in the face of the automatic stabilisers that will react to the “lacklustre” growth, is not a rational policy position.

That obsession will ensure that the big changes that have to happen in re-balancing spending etc will stall and we will end up in a malaise.

Conclusion

I haven’t had much time today and now I have to run for a flight home.

The point is that unless we understand the central role that the currency-issuing body (government) plays in aggregate demand we will keep making policy positions that undermine or exacerbate the trends in the private economy.

There is no doubt that the private behaviour is shifting back to what we might have considered to be more normal positions with respect to saving and consumption. That will require governments returning to their historically normal behaviour – which means that fiscal austerity or consolidation or whatever you might like to call it – is the anathema of that requirement.

That is enough for today!

I saw that article by David LLewllyn-Smith in the Fairfax press.I didn’t bother wasting my time reading it as I know his speed from his blog.He is just another prisoner of the conventional wisdom.

I actually agree with a fair bit of what David LLewllyn-Smith – who blogs at Macrobusiness under the handle “Houses and Holes” – says. Not everything of course, and another blogger at the same site is strongly pro-MMT (Delusional economics).

Bill,

German exports to Spain, Greece, Portugal, Ireland roughly account for 8% of Germany’s exports, while Greece alone represents roughly 1% of them. Hardly the pillar(s) of German growth, wouldn’t you say?

I think I’m not understanding parts of this. My understanding was that the characteristics 1-4 were definitely not descriptive of the Great Moderation.

Also, I always thought real wage growth supression in the USA dates back at least since the mid-1960s, about the time when credit growth kicked away from a long-term trend and the first post war banking crisis in the USA.

The extent to which modern capitalism requires large increases in household debt to sell its wares strikes me as one of the most troubling aspects of the economic system.

Bill,

If they did that without changing the policy by which the Reserve Bank sets interest rates, it would just make it worse, as they’d set interest rates higher (causing even more deleveraging) and banks trying to dodge the interest rate hike would become more reliant on the carry trade, pushing up our dollar even further.

And with a more sensible interest rate policy, there may not be any need for the government to support deleveraging, as borrowing would become more affordable.

But there is much doubt that it’s a long term change – it could just be cyclical.

The great moderation is a bit like Fukayama’s “End of History” malarkey. Ie. Characterized by alarming verbosity and arrogance, or “crap” for short. And a bit like economists trying to equate economics with physics (the ultimate expression of intellectual envy). The fact is that the great moderation was merely a series of higher troughs in GDP growth coinciding with a relatively flat cap on GDP growth at or just above 4pc (US). Even technical analysis, far from being “fundamental”, picks the large break lower in GDP, now known as the GFC. Not coincidentally, the Fed Funds rate was in a cracking downtrend over a couple of decades at least, with new lows in rates never returning to the previous peak. Ie. Continually pumping up the economy as credit growth made up for lost “real” income. Also not coincidentally, these (continually lower) troughs in Fed rates matched up with higher GDP troughs. No one ever seemed to wonder what was going to happen when the Funds rate inevitably reached zero! And Greenspan was called a genius for this.

As for Australia, the govt and RBA missed the telltale signs of economic growth moderation completely, obsessed withr the u-rate and being utterly unable to complete the mosaic that the economy is. They stood by watching credit growth stall, building approvals slump, and retail sales crater, and never really asking why. They ignored underemployment and insisted core inflation would not fall below 3pc, then made a ham fist of GDP all last year. It has been appalling to watch, and yet the govt as decided it can trump the stupidity in even grander style by insisting on tighter fiscal policy while the economy continues to struggle under the weight of it’s currency. The RBA is supposed to have substantial “business liaison” depts, but it doesn’t appear they talk (or listen) to anyone. It’s just a giant s—show.

One thing that does seem certain (to me) is that rates will probably keep falling … A lot. When major banks can still offer 6pc term depo rates for 6mths the day before the last RBA meet (and cut), you know something’s really stinking up the place. Looking forward to officialdom getting on the case ……

I wonder if there is a typo in this paragraph

“In many cases, where actual budget surpluses were recorded, the economies went into recession soon after. The important point though is that the deficits were made possible by the unsustainable growth in private credit which drove private spending and boosted tax revenue.”

Shouldn’t this be surpluses? If not, I am sorry, but I am lost here.

Just found out this interesting article in money history http://www.frontporchrepublic.com/2012/01/friends-and-strangers-a-meditation-on-money/ may be worth reading.

How can extra fiscal support be provided without it sustaining asset prices like housing that clearly need to go down?

Dear Richard1 (at 2012/01/17 at 22:54)

Thanks – it was a typo. I appreciate the vigilance.

best wishes

bill

Hello Bill Mitchell

This is one more of many articles that clarifies fiscal and monetary issues. My own historical and factual research substantiates the proposition that austerity policy of any type at a time of underemployment of existing productive capacity and high unemployment is not only inhumane but counterproductive. Lobbyists and ideologues for hose vested interests that benefit from such policies are in constant search of propaganda points to justify such irrationality.

In this comment, I want to call attention to a new issue, which could be addressed in an integrated fashion along with MMT analysis. A non economist William Greider has focused on both of these issues together.

I am going to add one dimension of the economic policy dilemma which requires consideration and rethinking in addition to macroeconomic policy as understood by most economists

One thing that I would like to see more of is how MMT assumptions interact with developments in trade and manufacturing. It seems to me that neoliberal economics and economics in general has failed to come to grips with the value of labor as an essential factor of production and the global economic dilemma caused by the entry into world labor markets of countries like China and Indoa and the effect this has on wages and employment in the developed countries. I believe that labor productivity and efficiency of labor should not be measured in terms of the global “market” price of labor but in terms of physical output per worker measured in terms of units of a particular product of a certain quality, say a computer, per hour worked. I believe the the drag on employment and wages in developed countries resulting from globalization and competition with countries that pay close to subsistence wages is undeniable. Many economists, like Stiglitz and Ha Joon Chang recognize the importance of tariffs and industrial policies in economic history. I believe that the losses to workers and the general population in industrialized countries, most particularly the United States is a serous problem. See the studies of the Economic Policy Institute or the works of observers questioning free trade agreements and free trade dogma. I believe that unless real labor productivity measured in terms of working hours is factored into economic analysis, the false rational of zero sum trade will continue to jeopardize living standards in advanced countries and contribute go enormous trade deficits and economic imbalance on a global scale. Beggar thy neighbor race to the bottom trade relations, are I believe unsustainable.

My question is how one can factor in Trade and Industrial policy theory and practice along with macroeconomic policy and theory in an explanation of the causes of growing inequality in the developed world and a threat to higher living standards. How would you address trade policy in conjunction with MMT other than through exchange rate manipulation which can’t be carried out by all countries at once? How can one bring in wages and a real labor theory of vallue into the equation?

If this a totally separate issue in economic study, I believe it shouldn’t be.

Thanks for any obsrvatons or future discussion of MMT in conjunction with trade and development issues. I am an economic historian trying to develop an integrated multidimensional understanding of the global economy and very much appreciative of the insights offered by MMT.

Thanks very much in advance for any comments or elaboration on these issues.

Alan Fogelquist

Hi Bill

Here’s a great MSM headline for you to have some fun with:

“Americans raid savings, putting recovery at risk: Workers pare back contributions to college funds and borrow from retirement accounts.”

LOL

Sean Fernyhough: My understanding was that the characteristics 1-4 were definitely not descriptive of the Great Moderation.

Bill should recast this paragraph. I can’t believe either that 1-4 refer to the “Great Moderation” (Great Stagnation). Pretty clearly the full employment era before it must be meant.

He must mean: “[the period before] the period before the crisis”.

Dear Sean Fernyhough (at 2012/01/17 at 20:34) and later Some Guy

Thanks very much for pointing out the confusion. I was typing the blog in a departure lounge and really wanted to finish it before the plane took off. Haste makes waste though. Sorry for wasting your time.

I have changed the text to render clarity.

best wishes

bill

MamMoTh,

There are two. ways to do that: either increase the housing supply or tax the land.

Hi Bill,

Have you ever posted anything about why floating currencies are so important? I’m reasonable familiar with the problems that arise from pegged currencies, but I’m worried that floating currencies are subject to speculation and “predatory” economic behavior. Would some sort of international agreement on currency valuation work–one including formal mechanisms to adjust as needed?

And just to be clear, I’m not referring to fiat vs. gold/commodity here, but simply the floating exchange rate. I always read here that fiat, floating currencies are necessary–why the second part?

@Bolo

Floating means the Government will not commit itself to ensure some sort of exchange with another currency. When they do that, they need to have foreign currency they can sell whenever their currency values and foreign currency they need to buy whenever their currency devalues.

The fact that a currency is floating doesn’t imply that it is open to predatory speculation – in fact, committing itself to defend an exchange rate makes it a whole lot easier, because the speculators know what will the reaction to the changes be.

Free floating currencies are as good as a casino for investment and they can always be protected from “predatory” behaviours using regulation without affecting the floating nature of the currency.

With a floating currency any predatory speculation remains within the private sector. Both counterparts are private individuals betting against each other. So although that might affect exchange rates it is less likely there will be an abrupt change like the devaluation that often follows a successful speculative attack on a fixed exchange regime.

Talvez and MamMoTh:

Thanks for the replies. I do have one question, based on MamMoTh’s comment–“predatory speculation remains within the private sector.” Can’t this activity end up damaging the private sector though? I understand it leaves government immune (assuming fiat, sovereignty, etc.), but couldn’t the speculation activity in the private sector be a drain on private sector productivity and growth, in much the same way that financial engineering on Wall Street has been a drain on more productive economic activity in the US?

Thanks!

Bill,

Can you give us one example of a successful country that has followed this Keynesian policy of continuous deficits to prevent deflation?

Just one will be enough to convince me of the practical nature of the theory.

Lew

Lew, the whole world during the postwar “Keynesian” full employment golden age was an example. The exceptional growth and prosperity during this era was due to the fact that macro-economics which basically made sense, had something to do with reality, was applied.

Bill wrote a book about this: Full Employment Abandoned. Contents See also Full employment abandoned: shifting sands and policy failures, which should give you the idea.

Some Guy,

So, what happened? All of those successful big-government countries have recently fallen into an economic black hole. The reason seems related to the debt load, at least a considerable part of the discussion claims that. Given the effects on the politicians of any downgrade of their country’s S&P rating, there is substance to that claim.

Given the difficulty of teasing out cause-and-effect in the very complex economic system, how can I even be convinced that the Keynesian policies were the cause of the ‘full employment golden age’?

Especially, given all of the studies that show that ‘total government burden’ == taxes + regulations is negatively correlated with the growth rate of the GDP? And the fact that all of the Communist countries who went in for serious management of their economies all died?

There are no longer any successful big-government countries, no matter how assiduously they pursued Keynesian policies. In fact, the bigger the debt, the faster they fell.

Perhaps someone can explain this for me?

Lew

Lew Glendenning,

I may try to explain but I am not sure whether this is going to work.

Things are not exactly as you stated. That’s why I urge you to read more of Bill’s blog – the most of points you have raised have nothing or very little to do with the economic theory called MMT.

NB I carefully avoid using this term in my own comments as I am a non-economist and my personal views may be a misinterpretation of what Bill wanted to say or may be not fully fully aligned with him.

Please do not teach us here about how communism was an extreme version of Keynesianism. Did you ever live in a communist country? Communism was not market-based at all. The dramatic change observed in the Chinese GDP growth rate was due to the introduction of the market mechanisms at the micro scale and limited private property rights especially private ownership of the means of production – while the central political structure was not dismantled at all. I am not a supporter of CCP but I saw a few things with my own eyes. The communist system in Eastern Europe was a total failure based on constant violation of human liberties but not all the communists were red pigs and these who replaced them in Eastern Europe are not much better than their predecessors. Did you see Moscov in the 1990s? This was the corrupt liberalism in action – total anarchy leading to stealing of the state property in the name of “privatisation”. The state was indeed very weak – to the point when Chechen warlords were able to carve up their own pseudo-state. Is this close to the ideal of the Tea-Party-like libertarians? (Of course not but this is what you get when you implement these naive ideas in real life).

I fully agree with you that over-regulation is bad. Who said that MMT equals “big government”? Haven’t you seen Warren Moslers’ proposals related to suspension of the certain taxes? To me he is a libertarian too but an “enlightened libertarian” not an ignorant one like some Tea Party followers. The fact that he also advocates Job Guarantee has very little with the size of the government. The failure of the markets has to be fixed. Can the markets fail? Can Say’s law be violated and the supply not bring about its own demand? If this happens, is it because of the intervention of the state, introduction of minimum wages, bureaucracy? Or is it an inherent feature of the system?

Please be aware that Post-Keynesian economics in general is not the same as the desexed version of Keynes you are familiar with if you read some “Neo-Keynesian” economists like Samuelson or Krugman. For the reasons why the Keynesian though was carefully desexed please read “John Maynard Keynes (Great Thinkers in Economics)” by Paul Davidson. It is not about the political attitude of Keynes who certainly wasn’t a social-democrat. It is about the removal of the essence of his models by the neoclassicals who tried to integrate his theory with their own system.

“Keynes’s argument was that if one accepted the fundamental axioms underlying classical theory, then Say’s Law was not formally (logically) wrong. Indeed Say’s Law is a logically consistent “special case” that could be obtained from Keynes’s General Theory by adding the three restrictive axioms: (1) the neutral money axiom, (2) the gross substitution axiom,

and (3) the ergodic axiom. These three classical theory axioms, however, are not applicable to a monetary economy where entrepreneurs organize the production process. Consequently, Say’s Law was not applicable to an entrepreneurial economy, and therefore classical theory is a special case whose “teaching is misleading and disastrous if we attempt to apply it to the facts of experience” (p 41-42).

People like Krugman think in terms of a “liquidity trap” and IS-LM model. In my opinion Paul Krugman still has no idea what caused the Great Recession as the IS-LM model is inconsistent with the endogenous money. The IS-LM model was recanted by its author, J.R.Hicks and is not an expression of theories developed by Keynes.

Once you correctly identify the Keynesian policies you may make up your own mind whether they worked or not. I think that they were instrumental in winning the Cold War by the West. NB the development of the modern Information Technology and many other great inventions were side effects of the arms race. Private sector enterprises did not land the first men on the Moon. If you look at the retardation of the American space program you will see the delayed results of the neoliberal “revolution” of the 1980s.

If you analyse the balance sheets of the economic entities you will discover that financial assets are either backed by government or private sector liabilities (there is a nice tool called “Macroeconomic Balance Sheet Visualizer” written by HBL, please Google for it). Excessive level and wrong distribution of the private debt is a serious problem which eventually leads to debt-deleveraging. This is in fact one of the root causes of the current malaise. In regards to sovereign government liabilities denominated in the domestic currency there is no solvency issue as long as the government abstains from doing silly things. The issue of how much income is redistributed in the interests can also be solved. Again I don’t want to debate the mainstream claims about the looming bankruptcy of the American state. Please read the relevant blog posts on the right-hand tab as your claims have already been debunked by Bill long time ago.

If you don’t like the level of government debt you have to admit that you also don’t like the level of financial savings of the non-government sector. There is an easy way to reduce the government debt – confiscate the savings. In fact I may think that this would not be silly in some cases (a capital tax) but you have every right to disagree with me. In that case please stop writing about the “problem” of public debt. This is a “problem” of excessive savings which you may not want to confiscate.

Anyway I urge you to follow the links on the right-hand side panel and discover the alternative world of economics not based on the pseudo-scientific axioms from the 18th century. I read much more than Bill’s blog but I count it among the best.

So, what happened? You could read Bill’s paper or book.

All of those successful big-government countries have recently fallen into an economic black hole. The reason seems related to the debt load, at least a considerable part of the discussion claims that. The ravings of the innumerate – the modern mainstream – claim that. The idea that the US or Japan could go bankrupt, that their debt could be unsafe, from default or serious inflation, is something which insults the intelligence of a ten year old. The “successful big government economies” are not in a black hole. The problem with the “debt load” is that governments have not been increasing it fast enough, fairly enough, by more targetted deficit spending.

There are no longer any successful big-government countries, no matter how assiduously they pursued Keynesian policies. In fact, the bigger the debt, the faster they fell.

Perhaps someone can explain this for me?

China is doing fine. It has been the most “Keynesian” of major economies since the crisis & before, and it has been doing the best. All signs are that it will continue to have superior performance, as long as the Chinese believe in accounting = MMT. While the rest of the world says – “What! Addition & Subtraction! WITCHCRAFT!”

Bigger the debt, faster they fell is simply wrong. Nobody can explain facts which aren’t. As Bill’s paper notes, the US was an exception – “the reality was that discretionary fiscal policy was still employed as before” until the Clinton surpluses, when the US accorded more closely with the neo-liberal model. And what happened was that the other “advanced” countries went whole-hog neoliberal earlier, and their unemployment statistics reversed. Europe etc tended to have lower unemployment than the USA, during the good years, but then higher when they abandoned fiscal policy and the USA didn’t. See the graph in his paper or book. Europe tended to spend sensibly, and the USA insanely, on numerous destructive welfare-for-the-rich (with confiscatory taxation for the poor) schemes, above all on militarism, but US high-calorie high-spending malinvestment beat European state-enforced anorexic good sense in terms of GDP growth & employment.

MMT is not about that enlarging that evil big government. It is about doing accounting & arithmetic right, whatever the size of the government. It is about understanding what money is. It is about consistently describing economies with any size of government. Its very general, very basic, recommendations apply to any monetary economy, from an Austrian night-watchman laissez-faire state to an evil totalitarian Stalinist economy. Right now, most of the economies of the world are austerity-mad, the USA a bit less so. Taxes too high, spending too low for the size of the government, economies and savings desires. Policies worldwide make no sense, unless one is trying to enrich the rich & impoverish the poor and middle class, and to hell with real growth, real wealth, jobs, progress, financial stability & human welfare.

Given the complexity of human biology, how can one tell that being guillotined is the cause of one’s head falling off? But empirically, one does observe decapitation after guillotining. And one has decent theories about why this should be so, and that is all one can ask for in any science, a decent, intelligible theory with decent empirical validity. Much the same in economics. While the measurement of economic decapitation – unemployment, slow growth etc may be a slightly harder than seeing whether someone retains his head or not, it is clear enough. And the theory in economics of why the equivalent of guillotining, the government spending too little, taxing too much, is bad for an economy is simpler than understanding the complicated physical process of guillotining.