The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

Latest ECB data shows how bad things have become in Euroland

I was reading the recently published January 2012 Monthly Bulletin from the ECB yesterday. It provides a massive amount of interesting data about the developments in the Eurozone plus analysis. The descriptive analysis is fine (this went up, this went down) but the conceptual analysis leaves a lot to be desired. This is an institution that still talks about reference values of broad money as a policy target to control inflation. Basically, that idea has no application in our monetary system. But that aside, the release of the latest M3 data tells us how bad things are getting in the Eurozone and do not augur well for the coming year, despite the up-beat forecasts for real GDP that the ECB are still providing. The latest ECB data shows how bad things have become in Euroland.

You will note that in Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) there is very little spoken about the money supply. In an endogenous money world there is very little meaning in the aggregate concept of the “money supply”. I will come back to that.

But the Central banks do still publish data on various measures of “money” and attach importance to movements in these data series.

Chapter 2 of the January ECB Monthly Bulletin covers “Monetary and Financial Developments”. The ECB said:

The annual growth rate of M3 declined strongly to stand at 2.0% in November 2011, down from 2.6% in October … On the one hand, three-quarters of this moderation in annual M3 growth is explained by a base effect related to sizeable interbank transactions traded via central counterparties (CCPs) in November 2010. On the other hand, the month-on-month growth rate was modestly negative at -0.15% in November.

In fact, the latest data available from the ECB shows that the M3 growth rate has decelined further (annualised) to 1.6 per cent in December 2011.

What is M3 and why might it tell us something significant about the current state of the Eurozone?

The ECB say that:

Broad money (M3) comprises M2 and marketable instruments issued by the MFI sector. Certain money market instruments, in particular money market fund (MMF) shares/units and repurchase agreements are included in this aggregate. A high degree of liquidity and price certainty make these instruments close substitutes for deposits. As a result of their inclusion, M3 is less affected by substitution between various liquid asset categories than narrower definitions of money, and is therefore more stable.

M3 is often the measure of the money supply that economists focus on with respect to their outlook for inflation. I will come back to that soon.

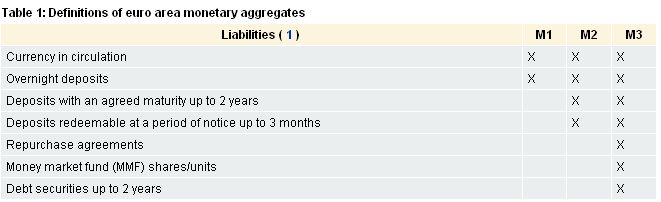

The following graphic is taken from the ECB Home Page and provides an easy reference to the increasingly broader definitions of the money supply.

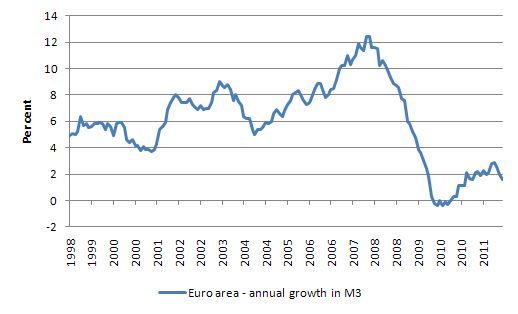

The following graph shows the annual growth in seasonally-adjusted M3 from September 1998 to December 2011 for the entire Eurozone. You can get the data from the ECB Data Warehouse if you are interested.

The ECB say that the:

Overall, as in October, the weak monetary developments continued to reflect the high levels of economic and financial market uncertainty … The slowdown observed in the annual growth of M3 in November mainly reflected sharp declines in the annual growth rates of marketable instruments and, to a lesser extent, short-term deposits other than overnight deposits.

I will return to this point later. But first some background.

Mainstream macroeconomists think that M3 is a child of the monetary base. Underpinning this notion is the concept of the money multiplier.

A central tenet of mainstream macroeconomics that follows from the concept of the money multiplier is that the central bank is to control the money supply.

Neither the money multiplier nor the concept of central bank control of the money supply is a valid representation of the way the monetary system operates even though it appears in all mainstream macroeconomics textbooks and is relentlessly rammed down the throats of unsuspecting economic students.

The money multiplier myth leads students to think that as the central bank can control the monetary base then it can control the money supply.

I covered the base money-M3 relationship in these blogs among several – Money multiplier – missing feared dead and Money multiplier and other myths. You can consult those blogs for further information.

Today, I am just focusing on the relationship between M3 and inflation.

But the claim that the central bank controls the money supply (M3) is embedded in students’ minds from the first-year of undergraduate study in economics.

For example, in Mankiw’s Principles of Economics (Chapter 27 First Edition) he says that the central bank has “two related jobs”. The first is to “regulate the banks and ensure the health of the financial system” and the second “and more important job”:

… is to control the quantity of money that is made available to the economy, called the money supply. Decisions by policymakers concerning the money supply constitute monetary policy (emphasis in original).

How does the mainstream economists claim the central bank accomplishes this task? Mankiw is representative of the plethora of textbooks that say that the:

Fed’s primary tool is open-market operations – the purchase and sale of U.S government bonds … If the FOMC decides to increase the money supply, the Fed creates dollars and uses them buy government bonds from the public in the nation’s bond markets. After the purchase, these dollars are in the hands of the public. Thus an open market purchase of bonds by the Fed increases the money supply. Conversely, if the FOMC decides to decrease the money supply, the Fed sells government bonds from its portfolio to the public in the nation’s bond markets. After the sale, the dollars it receives for the bonds are out of the hands of the public. Thus an open market sale of bonds by the Fed decreases the money supply.

This description of the way the central bank interacts with the banking system and the wider economy is totally false. The reality is that monetary policy is focused on determining the value of a short-term interest rate. Central banks cannot control the money supply. To some extent these ideas were a residual of the commodity money systems where the central bank could clearly control the stock of gold, for example. But in a credit money system, this ability to control the stock of “money” is undermined by the demand for credit.

MMT assumes that the central bank has very little capacity to control the monetary aggregates.

The theory of endogenous money is central to the horizontal analysis in MMT. When we talk about endogenous money we are referring to the outcomes that are arrived at after market participants respond to their own market prospects and central bank policy settings and make decisions about the liquid assets they will hold (deposits) and new liquid assets they will seek (loans).

For a discussion of the difference between vertical and horizontal transactions in a modern monetary economy please see Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 and Deficit spending 101 – Part 3.

The essential idea is that the “money supply” in an “entrepreneurial economy” is demand-determined – as the demand for credit expands so does the money supply.

As credit is repaid the money supply shrinks. These flows are going on all the time and the stock measure we choose to call the money supply, say M3 (Currency plus bank current deposits of the private non-bank sector plus all other bank deposits from the private non-bank sector) is just an arbitrary reflection of the credit circuit.

So the supply of money is determined endogenously by the level of GDP, which means it is a dynamic (rather than a static) concept. This means that the latest developments in M3 in the Eurozone are telling us something very clear about what is going on it that economy.

Central banks clearly do not determine the volume of deposits held each day. These arise from decisions by commercial banks to make loans. The central bank can determine the price of “money” by setting the interest rate on bank reserves.

Further expanding the monetary base (bank reserves) as we have argued in recent blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – does not lead to an expansion of credit.

So why do the mainstream place so much attention on measures such as M3?

The answer is that they believe that inflation is the result of the money supply growing too fast.

Take the following statement from Box 2 of the ECB Monthly Bulletin noted above:

While there is abundant evidence that money growth has leading indicator properties for inflation in the medium to long term, these properties may be weaker during specific periods. This is particularly the case in periods characterised by significant variation in money demand triggered by increased uncertainty regarding the economic environment, when money balances may be held primarily for precautionary or portfolio-related reasons, rather than for transaction purposes … The heightened tensions observed in sovereign bond markets since August 2011 have increased financial stress in the euro area banking sector and the wider financial system. These elevated stress levels, which are a reflection of various types of uncertainty, have also affected monetary developments in the euro area.

This is, of-course also straight out of a mainstream macroeconomics textbook.

It is based on the defunct Quantity Theory of Money (QTM), which is the principle mainstream framework used to explain the price level (and movements in it).

The QTM was used by Classical economists to explain the price of goods. The value of money = 1/p (the inverse of the price level) is determined by demand for and supply of money. There were two versions of this theory: (a) the flow version – Irving Fisher; and (b) the stock version – Marshall, Pigou and Keynes (so-called Cambridge equation).

The flow version is straightforward and best known by lay audiences and is still used by those who want to draw a connection between the money supply (or its rate of growth) and inflation.

In the Classical model, the price level is determined by: MV = PY

M = stock of money balances; V = velocity of circulation (how many times per period the stock of money turns over in transactions); Y = full employment output and P = price level. PY is nominal GDP.

MV is the flow of $s per period and PY is the flow aggregate demand of $s per period. If you think about the MV = PY equation then from a transactional viewpoint it has to hold. It is an accounting statement. All the transactions (left-hand side) have to equal the value of production (right-hand side). That doesn’t get us very far.

What the Classical economists wanted to assert was that if MV > PY then the change in prices was assumed to be positive, and if MV < PY then the price level would fall. Clearly, a steady-state situation was when MV = PY. To explain the price level (P) the Classical economists had to impose behavioural stipulations on V (fixed) and full employment (Y fixed). Then it became clear that the change in M would directly impact on the change in P (that is, inflation). So Classical theorists (and monetarists and more modern variants) had to make some assumptions or assertions about the behavioural nature of the variables underlying the accounting identity. So they assumed that V is constant and ground in the habits of commerce - despite the empirical evidence which shows it is highly variable if not erratic. They also assumed that Y will always be at full employment because they invoke flexible price models and assume market clearing - so they take Y to be fixed. This just asserts the real model derived above which includes the denial of unemployment. This is a case of blind devotion to theory stopping the economist looking out the window and seeing regular periods when productive resources are anything but fully employed. But with these assumptions - any child could then conclude that changes in M => directly lead to changes in P because with V assumed fixed the left-hand side is driven by M and if Y is assumed to always be at full employment then the only thing that can give on the right-hand side of the accounting identity is P.

The assertion that the real side of the economy (output and employment) are completely separable from the nominal (money) side and that prices are driven by monetary growth and growth and employment is driven wholly by the supply side (technology and population growth), rests on the assertion that the economy is always at full employment (quite apart from the nonsensical assumption that V is fixed).

Anyone with a brain could tell you that if business firms can respond to higher nominal spending (that is, higher $ demand) – either by increasing production or increasing prices or increasing both – and they cannot increase production any more (because the economy is at full employment) then they must increase prices to ration the demand.

That is a basic presumption of MMT. But typically, firms prefer to respond to demand growth in real terms to maintain their market share and thus invest in new capacity if they think spending will grow in the future and vice versa.

The overwhelming evidence is that the macroeconomy quantity adjusts rather than price adjusts to nominal aggregate demand fluctuations when there is excess capacity. Otherwise firms risk losing market share.

So, when the economy is in a state of low capacity utilisation with significant stocks of idle productive resources (of all types) then it is highly unlikely that the firm will respond to a positive demand impulse by putting up prices (above the level that they were before the downturn began). They might stop offering fire sale prices but that is not what we are talking about here.

This should discourage you from automatically linking growth in the M3 and inflation. There is no link.

Inflation is driven by nominal aggregate demand growth that exceeds the capacity of the economy to respond in real terms – that is, to increase output. There are a myriad of reasons why this situation could emerge and some of these reasons implicate poor government policy decisions.

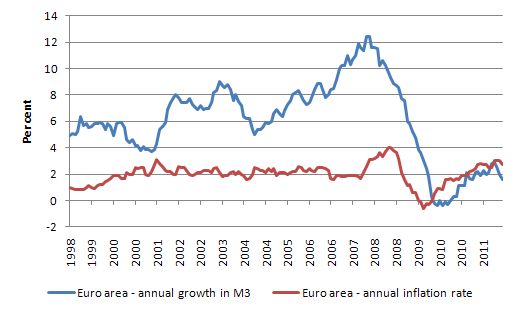

Consider the following graph which adds the annual Eurozone inflation rate to the M3 growth rate depicted in the previous graph. It is very hard to divine a relationship between the growth in M3 (blue line) and the inflation rate (red line).

In one of its earliest Press Releases (December 1, 1998) – The quantitative reference value for monetary growth – the ECB demonstrated its obsession with M3 and attempting to control it.

In that Press Release, the ECB said it main role was to achieve “price stability” (that is, stable inflation) and that this meant a “year-on-year increase in the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) for the euro area of below 2%”.

They “outlined the two main elements of the strategy that it will use to achieve the objective of maintaining price stability”. The first of these elements was that:

… a prominent role will be assigned to money. This role will be signalled by the announcement of a quantitative reference value for the growth of a broad monetary aggregate.

They continued to say that the “reference value will refer to the broad monetary aggregate M3” and that:

Deviations of current monetary growth from the reference value would, under normal circumstances, signal risks to price stability …

And that this “reference value” should be “consistent with – and serve the achievement of – price stability”. So some calibration was in their minds.

They then went on to paraphrase Quantity Theory of Money concepts:

Furthermore, the reference value for monetary growth must take into account real GDP growth and changes in the velocity of circulation. In view of the medium-term orientation of monetary policy, it appears appropriate to base the derivation of the reference value on assumptions about the medium-term trend in both real GDP growth and velocity growth.

Note they slip trend rate of real GDP growth in place of full capacity real GDP growth and thus embed persistent unemployment into the framework.

The ECB then defined their “reference value for monetary growth” to be 4.5 per cent per annum and claimed that they would:

… monitor monetary developments against this reference value on the basis of three-month moving averages of the monthly twelve-month growth rates for M3. This will ensure that erratic monthly outturns in the data do not unduly distort the information contained in the aggregate, thereby reinforcing the medium-term orientation of the reference value.

Which all means that they thought that:

1. 4.5 per cent per annum would deliver a 2 per cent inflation rate, given their estimates of real GDP growth and velocity of circulation.

2. They could actually control the growth of M3.

The previous discussion has shown why the central bank cannot achieve Aim 2 – control of M3.

But what about the empirical side of it?

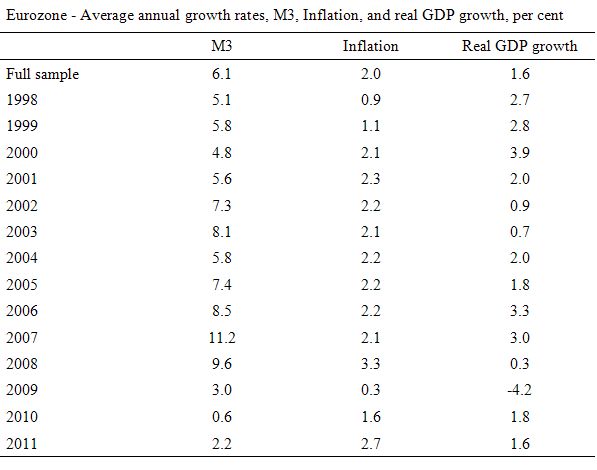

I constructed this table which shows the average annual growth rates in M3, inflation and real GDP in the Eurozone from 1998 (last 4 months) to 2011. The full sample is September 1998 to December 2011.

What does this tell us?

1. The ECB was spectacularly unsuccessful in controlling M3 to keep to its reference value of 4.5 per cent per annum.

2. Inflation showed now relationship to M3 growth.

3. The implied velocity of circulation was far from stable.

4. The M3 reference value concept is a nonsensical indicator and reflects the poverty of intellectual development in mainstream monetary economics.

The data shown in the graphs and the Table however is readily comprehensible in terms of MMT. M3 growth has stopped because people are not borrowing.

The ECB note in the January Monthly Bulletin that in seeking to understand why M3 growth is so low we might look at the banking system counterparts:

As regards the counterparts of M3, the annual growth rate of MFI credit to euro area residents declined to 0.8% in November, down from 1.6% in the previous month … The annual growth rate of credit to the private sector declined to 1.0% in November, down from 2.1% in the previous month. This reflects MFIs shedding holdings of both equity and debt securities, as well as a reduction in MFI loans. The monthly outflow for MFI loans to the private sector (adjusted for sales and securitisation) almost equalled that observed for loans held on MFIs’ balance sheets, suggesting that loan sales and securitisation activity were subdued in November.

Which means quite simply that the private sector is not borrowing at present. The period of strong growth in M3 was the result of strong credit creation by the commercial banks as private borrowers fuelled the consumption and real estate binge in the period leading up to the crisis.

That has come to an end now and so has the growth in M3.

This also reflects on the way the mainstream view banking.

The illusion is that a bank is an institution that accepts deposits to build up reserves and then on-lends them at a margin to make money. The conceptualisation suggests that if it doesn’t have adequate reserves then it cannot lend. So the presupposition is that by adding to bank reserves, quantitative easing will help lending.

But banks do not operate like this. Bank lending is not “reserve constrained”. Banks lend to any credit worthy customer they can find and then worry about their reserve positions afterwards. If they are short of reserves (their reserve accounts have to be in positive balance each day and in some countries central banks require certain ratios to be maintained) then they borrow from each other in the interbank market or, ultimately, they will borrow from the central bank through the so-called discount window. They are reluctant to use the latter facility because it carries a penalty (higher interest cost).

The point is that building bank reserves will not increase the bank’s capacity to lend. Loans create deposits which generate reserves.

The reason that the commercial banks are currently not lending much is because they are not convinced there are credit worthy customers on their doorstep. In the current climate the assessment of what is credit worthy has become very strict compared to the lax days as the top of the boom approached.

The growth in M3 is driven by demand for credit which reflects the strength of the economy.

Conclusion

The latest ECB data shows that the private sector is in a bunker and not seeing much future for spending growth in the Eurozone.

The ECB say very little about the damaging effects of fiscal austerity – read nothing other than this:

At the same time, the announcement of additional austerity measures by some euro area governments helped to alleviate tensions in the markets.

The problem is that the austerity if undermining the banks and the “markets” broadly defined by reducing real GDP growth and destroying the motivation for private households and firms to expand credit within safe parameters.

The slow growth of M3 is indicating that.

That is enough for today!

And the financial sector flows should enhance the falling money supply. If export revenue, if any, is falling due to recession and unemployment, if the private sector is not borrowing, that leaves austere governments to inject much needed capital. Good luck with that with Merkel looking over your fiscal shoulder. Without adequate money in circulation to buy goods and services and sustain export leakages, well that’s contraction-expansion, I guess. Furthermore, if sovereign governments not only make coupon payments rolling over debt but tax more than they spend to reduce the debt principle, well good luck finding enough money circulating to fund soup kitchens.

The ancients believed that the earth was the centre of the universe.A great deal of effort was expended explaining the apparently bizarre behaviour of the planets to fit this concept.

There was a lot of opposition to the concept of a heliocentric solar system as proposed (with a great deal of caution) by the likes of Copernicus and Galileo.

It seems that MMT is in much the same sort of bind as heliocentrism was.Such is the power of the herd instinct and fashionable thinking.

Monetary aggregates also include lending abroad by foreign lenders. Even if a non-Euro bank makes a EUR loan in, say, Japan, then EUR monetary aggregates inevitably have to change because such lending should involve a European bank settlement. In the end liquidity regulations and individual bank preferences will push at least to some extent such balance sheet items out of the interbank market into non-bank and/or security based financing.

Do we know which repo agreements the ECB records in the M3 aggregate? The repo market is more than 6 trillion Euros and yet only a few hundred billion are recorded in the M3.

Give that the ECB has been relatively successful in hitting the 2% target inflation rate, but very unsuccessful in hitting the reference growth rate in M3, which is the supposed theoretic basis for the inflation rate, what accounts for the success in hitting the inflation target?

There seems to be strong residual component in inflation, even when aggregate demand is flatlining or falling, inflation remains positive. Explanation for this must be found on micro-factors rather than growth in nominal spending.

I think employers want to give annual pay rises to their employees to keep them happy. It’s part of a total compensation that employees get from work. You got your wages, and you got annual wage rises. Small perks like this can boost morale.

Employees have come to expect these so it feels like betrayal if wages remain flat. It takes much more devastating economic conditions than regular recession to kill of expectations of wage raises. It’s like killing of hope of better future. People are optimistic by their very nature.

And then there are countries with strong labour union movements where inflation is driven by altogether different dynamic. Unions typically compete amongs each other over their share of national income pie. And union bosses have to prove their worth to their constituancies.

You analyis is similar to Steve Keen’s (see papers on his Debtwatch site). However, the dynamics of debt (credit) buildup during a leveraging age (end of WW2 to about 2007) is not addressed in your blog above. We are in a deleveraging age now, which could last decades. Hence, M3 is contracting or growing at a much slower rate.

Nicely explained. Thanx a lot.

Bill,

I have been critical of the UK’s MPC inflation target of 2% when it has been over 4.5% for years (latest water bills/rail fare increases have been 5+%). Perhaps they were mistakenly using ECB’s M3 target by default?

Bill,

Money supply in UK appears to have dropped to 1.4% so does MPC have its targets reversed viz M3 & inflation?

More QE for the UK soon!

I’ve always found one aspect of the “money supply” story curious. Which is that, given that the money supply is ever-increasing, if the Fed raises the money supply by buying bonds on the open market, then it would necessarily end up owning all the bonds. The story makes no sense from a basic stock-flow standpoint.

Burk: Make sure you don’t confuse the Money Supply with the Money Base. Fed Open Market Operations are about adding or subtracting from the Money Base. Also, the total amount of government bonds obviously increases over time as well.

Hi Bill,

thanks for another nice myth busting post. I entirely agree with your analysis. The quality of economics texts is absolutely diabolical on such issues. I was lucky enough to be pointed towards Basil Moore and Dow/Savile’s book (“a critique of monetary policy”) when I was a student, and I’m eternally grateful. It is great to see people like yourself willing to point out with such clarity the flaws underpinning much economic “analysis” of monetary systems.

But, even if we treat M3 as a residual statistic, the expansion of monetary aggregates presumably tells us something about what is going on in the credit markets, and if monetary expansion is shooting way ahead of GDP growth for a sustained period (cf your chart on M3 growth in this post shows very fast and sustained expansion from 2003 or so until the crash in 2007/8) this begs the question – why? I presume you would accept that a central bank might be very legitimately concerned with what is going on in the aggregates from an indicator point of view, if nothing else ?

Dear Bill,

An interesting point about the ECB’s target of harmonized Euro inflation is that this is a hypothetical variable that directly affects almost nobody. In reality each country has its own inflation rate, and so even if the ECB could hit their inflation target that would have a very different impact in different countries. This graph from Krugman’s blog is a nice illustration of would the nice steady 2% looks like in practice:

GDP deflators

Richard (February 1, 2012 at 1:48),

Keen, like Keynes, distinguishes between money and debt.

Mitchell “is very little spoken about the money supply” and seems to lump money and debt all together as ‘financial assets’ — apparently forgetting about the bookkeeping entries that show debt as a liability.

When one speaks of NET financial assets, private debt pretty much has to zero out. But overlooking debt is the problem that created the problem that we’re in today.

The ideas behind MMT seem self-evident. What bothers me is that the people who run the ECB etc. & the UK treasury aren’t ignorant or stupid(I think). Why on earth do they keep pretending that they have run out of money, for example, in the UK (& the US) when that clearly cannot happen? The only answer has to be – it is a con, a swindle perpetrated by people who, by dint of being very wealthy, have come to believe they are entitled to become our new feudal lords. But because they achieve this domination using methods which are opaque to most, (& also “boring” & “nerdy” to the masses), they get away with it, even though the billions acquired with these “boring ” things is far from boring. Meanwhile, people are really suffering in the *real* world – in the UK we haven’t seen the worst of it yet as Osborne & friends funnel money from the people to the 1%.