Today (January 22, 2026), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the latest labour force…

The costs of unemployment – again

One of the extraordinary things that arose in a recent discussion about whether employment guarantees are better than leaving workers unemployed was the assumption that the costs of unemployment are relatively low compared to having workers engaged in activities of varying degrees of productivity. Some of the discussion suggested that there were “microeconomic” costs involved in having to manage employment guarantee programs (bureaucracy, supervision, etc) which would negate the value of any such program. The implicit assumption was that the unemployed will generate zero productivity if they are engaged in employment programs. There has been a long debate in the economics about the relative costs of microeconomic inefficiency compared to macroeconomic inefficiency. The simple fact is that the losses arising from unemployment dwarfed by a considerable margin any microeconomic losses that might arise from inefficient use of resources. in this blog, I discuss some of those issues.

I last visited this issue in some detail in this blog – The daily losses from unemployment. In terms of estimates, not much has changed in the US economy over the last 2 years. The daily losses in income alone are enormous.

One of the strong empirical results that emerge from the Great Depression is that the job relief programs that the various governments implemented to try to attenuate the massive rise in unemployment were very beneficial. At that time, it was realised that having workers locked out of the production process because there were not enough private jobs being generated was not only irrational in terms of lost income but also caused society additional problems, such as rising crime rates.

Direct job creation was a very effective way of attenuating these costs while the private sector regained its optimism. In fact, it took about 50 years or so for governments to abandon this way of thinking. Now we tolerate high levels of unemployment without a clear understanding of the magnitude of costs that that policy position imposes on specific individuals and society in general.

The single most rational thing a government could do was to ensure that there were enough jobs to match the available labour force.

In the growth period before the current crisis few countries had returned to the full employment states that they achieved in the Post World War 2 period up until the mid-1970s when the OPEC oil shocks led to a paradigm change in macroeconomic policy setting. The neo-liberal approach emphasised fiscal austerity to support an increasing reliance on monetary policy for counter-stabilisation.

So already in this period of relatively better economic growth there were substantial losses being recorded both in terms of lost GDP (production and income foregone) and the additional personal and social costs that accompany persistent unemployment.

It is well documented that sustained unemployment imposes significant economic, personal and social costs that include:

- loss of current output;

- social exclusion and the loss of freedom;

- skill loss;

- psychological harm, including increased suicide rate (which I will return to later);

- ill health and reduced life expectancy;

- loss of motivation;

- the undermining of human relations and family life;

- racial and gender inequality; and

- loss of social values and responsibility.

Many of these “costs” are difficult to quantify but clearly are substantial given qualitative evidence.

In the past I have done work on this with a colleague Martin Watts and you can see an early working paper (subsequently published but the working paper is free), which outlined the sort of method we used to compute the “costs of unemployment”.

There is a lovely quote from 1977 (Page 468) by the late James Tobin, which economists who read the blog will relate to:

Any economics student can expatiate on the inequities, distortions, and allocation of inefficiencies of controls or guideposts or tax rewards and penalties. But just consider the alternative. The microeconomic distortions of incomes policies would be trivial compared to the macroeconomic costs of prolonged underemployment of labor and capital. It takes a heap of Harberger triangles to fill an Okun Gap.

[Reference: Tobin, J. (1977) ‘How Dead is Keynes?’, Economic Inquiry, 15(4), 459-68].

Arnold Harberger was a University of Chicago economist/econometrician who coined the term “Hargberger Triangle” to denote the graphical area in a demand and supply graph that measures the deadweight loss arising from taxation. The triangle became an oft-used graphical device to portray microeconomic or so-called welfare losses in a variety of “markets”.

An Okun’s Gap (named after the US economist Arthur Okun) measures the loss in real output (income) arising from unemployment when an economy is operating below full employment because of demand constraints.

For afficionados, you might like to read this Letter to a Younger Generation which was written in 1998 by Arnold Harberger who is now 87 years old. He reflects on this quote.

Harberger said that:

Tobin was implicitly attributing as a social cost the entire gap between actual and potential GDP, and by innuendo criticising the approach of measuring costs solely in terms of the types of distortions usually considered in applied welfare economics. In effect, he was saying that the distortions approach misses the point, that it fails to capture the lion’s share of the real costs of a shortfall of output.

The simplest calculation reveals that the daily income losses alone of having that many people idle dwarf any reasonable estimate of microeconomic losses arising from the so-called “structural inefficiencies” or microeconomic rigidities (a favourite of the IMF) that have dominated public debate over the neo-liberal era.

It is just plain madness to ignore huge costs and then go about pursuing small costs (if they exist). One of the problems is that in pursuing these micro costs the government almost always will increase the macroeconomic costs.

We know that the losses encountered during a prolonged recession reverberate into tortured recoveries and that the damage that unemployment causes spans the generations.

Even before the crisis hit, these costs in most countries were huge as policy makers began using unemployment as a policy tool rather than a policy target as the obsession with inflation-targetting took hold.

Most people do not consider the irretrievable nature of these losses. Every day that unemployment remains above the full employment level (allowing for a small unemployment rate arising from frictions – people moving in-between jobs) the economy is foregoing billions in lost output and national income that is never recovered.

The magnitude of these losses and the fact that most commentators and policy makers prefer unemployment to direct job creation, shows the powerful hold that neo-liberal thinking has had on policy makers. How is it rational to tolerate these massive losses which span generations?

As noted, to some extent these losses are a mystery to society in general. While the unemployed and their families are certainly aware of them, the remainder of the society are less aware. For example, we might notice rising crime rates in our neighbourhoods but do not associate it with unemployment.

Neo-liberalism has also changed the way we think about unemployment. In the past we understood clearly that it arose as a result of a shortage of jobs.

However, in recent decades, we have been conditioned by a relentless (lying) press and government statements to perceive unemployment as an individual problem. So the unemployed are type-cast as being lazy; having poor work attitudes; refusing to invest in appropriate skills; and subject to disincentives arising from misguided government welfare support, and all the rest of the arguments that mainstream uses to obfuscate the social problem.

The focus in the public debate is to “blame the victim” and suggest that most are unemployable and prefer to live on welfare, where that support is available.

The overwhelming evidence from the informed research literature is that almost all the unemployed (when surveyed) prefer to work and are willing to take work if offered.

The overwhelming evidence from studies in most countries suggests that the unemployed are highly motivated to find work and are victims of a shortage of jobs rather than personal/individual deficiencies.

The dominance of the neo-liberal ideology led governments in most countries to have eschew the adoption of policies of direct job creation to reduce the rate of unemployment and to minimise these massive costs. Fiscal policy has became geared to the achievement of budget surpluses as some sort of token of prudent financial management.

After the release of the OECD Jobs Study, employment policy shifted from a demand-side emphasis (ensuring there were enough jobs) to a supply-side focus (active labour market policy) which targetted individuals with futile training programs divorced from a paid-work context and pernicious welfare-to-work rules.

While the governments were pursuing labour market deregulation and attempting to retrench the Welfare State in the face of persistent unemployment they were also deregulating financial markets. The lack of oversight of the latter is the fundamental reason we are now enduring the worst crisis in more than 80 years.

Method

While the previous work I have done on this topic has sought to compute the broadest possible measure of costs, in this blog I just focus on lost GDP income.

In focusing on the foregone output resulting from unemployment and underemployment you have to decide a benchmark to measure the current situation against.

In the work that follows, I used the low-point unemployment rate prior to the crisis – for the US 4.45 per cent in December 2006 and the high-point participation rate prior to the crisis – 66.3 per cent for the US.

The high-point participation rate allows us to adjust the labour force to eliminate the cyclical decline that occurs in a crisis as the discouraged workers who stop looking for work are not counted by the statistician as being unemployed. Economists call these people the hidden unemployed – they would work immediately if a job was offered to them.

The use of the low-point unemployment prior to the crisis is just a convenience and does not presupposes that this level was a full employment state.

The question being asked is: What are the daily GDP losses arising from the increases in the unemployment rate as a result of the crisis.

The data used is available from the US Bureau of Labour Statistics and the US Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Some facts – the peak labour force participation rate in the US occurred in December 2006 (66.3 per cent). The low-point unemployment rate was achieved in the same month (4.45 per cent).

The real GDP peaked accrued in December 2007. The average gross in real GDP between December 2003 and 2007 was 2.8% per annum. We use this period as a representative period of stable growth.

Note, the calculations assume that the full employment unemployment rate is 4.45 per cent, which may be a conservative estimate. It certainly doesn’t bias the results upwards.

First, I computed potential employment – which is the employment level that would have existed if the participation rate had have remained at its peak value given the actual underlying population growth that has occurred.

So we’re correcting for the cyclical decrease in participation rates that has occurred as a result of the crisis.

The unemployment rate used here was the low-point unemployment rate that the US economy sustained in December 2006.

Second, I computed potential GDP using the potential employment levels multiplied by actual labour productivity (real GDP per person employed). So this series tells us what real GDP would have been if employment was at its potential level (defined above) and those workers were producing the average GDP per unit. Note that the concept of potential in this case does not mean the maximum GDP that could be produced.

Remember the selective way I am defining potential employment – as a departure from the maximum achieved prior to the crisis.

Further, some will ask – why use average productivity when it is obvious that the unemployed are typically drawn from the lowest productivity pool? Surely putting these people back to work will not generate average productivity per person. That is true but not relevant in this case. By using actual labour productivity series I am probably understating the production gains that would occur given that labour productivity slumps during a downturn.

But to allay fears, I also computed a 2nd potential GDP series, which assumes that all the unemployed above the 4.45% level, would achieve a productivity level 50% below the normal productivity levels achieved in the US economy.

It is of course impossible to determine the productivity profile of the unemployed. Some of the unemployed will have productivity close to the economy wide average, while others will have substantially lower productivity.

The calculations abstract from these differences by assuming that all the unemployed can only function at half the rate of the existing employed. I judge that this is a conservative assumption, which will not bias the results upwards.

Third, I calculated the daily real GDP losses in billions of dollars per day for the US by dividing the gap between actual and potential real GDP by the number of days in each quarter.

This approximates the daily loss in real income that is permanently foregone by allowing unemployment to remain either above the level that was achieved immediately prior to the crisis.

Results

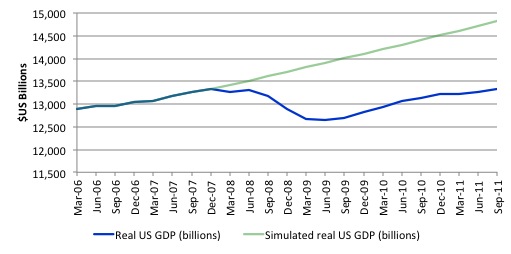

The following graph compares the actual real GDP series since the March-quarter 2006 (to September-quarter 2011) with the simulated real GDP series for the US based the assumption that real GDP continued to grow at the average rate of real GDP between December 2003 and the had held for the 8 quarters prior to the peak (that is, 2.8 per cent per annum).

The scale of the current crisis and lost income is clear from that graph.

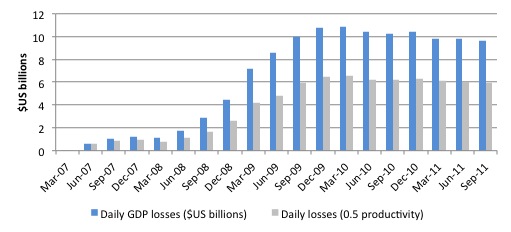

The next graph shows the calculations of the daily losses in real GDP (national income) for the two different productivity assumptions employed.

The daily GDP losses that the US economy is enduring as a result of the decline in economy activity below it previous peak are shown in the following graph. You can see that in the September-quarter 2011 these stood at $US9.7 billion per day.

Just say it to yourself – every day the US government is allowing $US9.7 billion to go down the drain in lost income just because they are too stupid to implement sensible direct job creation strategies.

Even with the conservative productivity assumption the daily losses are of the order of $US6 billion per day.

There has been a marked unwillingness by the US government to engage in direct job creation. How can these deadweight daily losses be justified? The policy inaction is culpable in the extreme in this regard.

For the reasons I have explained in the introduction, these estimates are just the starting point – they only cover real income losses arising from foregone production.

While they are bad enough, once you start adding in the other losses that have itemised above – the social, health, crime, etc costs – then you have a national catastrophe on your hands.

Suicides and the business cycle

I read an interesting academic paper the other day which contributed to the large literature that finds that the rate of suicides rise when unemployment rises and vice versa.

The study – Impact of Business Cycles on US Suicide Rates, 1928-2007 – was published in American Journal of Public Health in June 20011 and written by researchers from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

The publication was accompanied by a CDC Press Release.

The study “examined the associations of overall and age-specific suicide rates with business cycles from 1928 to 2007 in the United States”.

They defined a crisis as “the state of affairs provoked by a sudden and severe economic recession” and pointed out that “(m)ost recessions in history have been mild”.

They suggest that the:

… association between suicide and unemployment can be traced back to Durkheim,15 who stated that unemployment weakens a person’s social integration and increases suicide risk.

In addition, they discussed the so-called vulnerability model “which suggests that unemployment may result in limited access to supportive re- sources, thereby increasing the impact of stressful events and then suicide risk.”

Further, the:

… indirect causative model indicates that unemployment may bring about relationship difficulties or financial problems that may lead to events precipitating suicide.

They do not dismiss the possibility that both suicide and unemployment are actually driven by a 3rd factor. The research aims to disentangle these influences.

I won’t discuss the statistical methodology here because, if you’re interested, you can read the paper yourself.

Overall, they found:

1. “the overall suicide rate generally increased in recessions, especially in severe recessions that lasted longer than 1 year”.

2. “The largest increase in the overall suicide rate occurred during the Great Depression (1929-1933), when it surged from 18.0 in 1928 to 22.1 (the all-time high) in 1932, the last full year of the Great Depression.”

3. “Not only did the overall suicide rate generally rise during recessions; it also mostly fell during expansions.”

4. “the overall suicide rate rose relatively in 11 of 13 recessions, suggesting the countercyclical nature of the overall suicide rate”.

In terms of policy recommendations the study provides three strategies:

– Providing social support and counseling services to those who lose jobs or homes

– Promoting individual, family, and community connectedness, ie greater degrees of social integration (e.g., number of friends, high frequency of social contact, low levels of social isolation or loneliness); positive attachments to community organizations like schools and churches; and formal relationships between support services and referring organizations help ensure services are actually delivered and promote a clients’ well-being (as in the case of the primary care system and the mental health system) all serve as protective factors against suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

– Increasing the accessibility of prevention services (e.g., crisis centers and other community services).

I found these recommendations to be useful but disappointing nonetheless.

If there is a strong relationship between the suicide rate and unemployment in the most effective response from government should be to reduce unemployment. Mass unemployment can only be reduced by job creation.

When private spending is weak, public spending has to fill the gap. The best way to attenuate the massive costs – both direct and indirect – that arise from unemployment, is for that public spending to be concentrated on job creation.

These insights bear on the debate about the relative costs and benefits of using unemployment versus employment buffer stocks to maintain price stability.

Please read my recent blogs – Whatever – its either employment or unemployment buffer stocks and MMT is biased towards anti-crony – for more discussion on this point.

In 1978 while still a student at the University of Melbourne and in recognition of the then rising economic and social costs of unemployment, I formulated an early model of what I now call the Job Guarantee approach to full employment.

It wasn’t a new thought – public sector job creation as an antidote to cyclical unemployment was the norm in those days. Others have since independently proposed large-scale job creation.

I considered that the JG would work under the principles of a buffer stock mechanism (which were common in agricultural policy during that period) and the jobs would be designed to increase per capita social welfare by satisfying social needs that are not met by the private sector in areas including environmental services, community and social services, health and education.

Thus this increase in public sector employment would contribute to the reduction in the negative externalities that tend to increase with increasing levels of production by increasing the share of final output that is associated with green, public sector employment.

But the buffer stock would also ensure price stability, a point that my friend Warren Mosler independently came up in the early 1990s. That recognition helped consolidate our working relationship since then that has evolved into Modern Monetary Theory with the input of several others (Randy, Stephanie, Pavlina, Mat, Scott to name the early contributors).

The current crisis should make it obvious that unemployment arises when there are too few jobs being created (net) relative to the available labour force.

But despite the transparency of the causes of mass unemployment governments have failed to use direct job creation as a way of dealing with the rising costs associated with the joblessness. The vestiges of neo-liberal ideology are proving hard to shake.

If governments had have had a Job Guarantee in place there would be hardly any discernible rise in official unemployment and the costs of the crisis would have been significantly reduced. Yes there would have been some skills-based structural underemployment (high skills workers taking Job Guarantee jobs) and some obvious loss of income.

But overall these losses would have been attenuated and some of the other costs would have been mostly negated. For example, most (if not all) workers would not have been in danger of losing their homes. The contagion factors in this crisis would have been limited.

Conclusion

Even under conservative assumptions, the economic and social costs of sustained high unemployment are extremely high. The inability of unemployed individuals and their families to function in the market economy gives rise to many forms of social dysfunction, in addition to output loss.

The apparent failure of neo-liberal supply side policies to reduce unemployment prior to the crisis is now highlighted during the crisis.

There is now an urgent need to address the large pools of unemployment in world economies.

The daily income losses alone are enormous and overwhelm other inefficiencies notwithstanding the productivity heterogeneity that exists across the workforce.

There is no financial reason why the government should not deal with this problem directly by introducing a Job Guarantee as a starting point. Then broader investment in public infrastructure could follow according to political preferences. If the Government had the political will, it could readily overcome the problem of persistently high unemployment.

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be available sometime tomorrow. I hope everyone gets 5/5 so I can stop writing them.

That is enough for today!

“How can these deadweight daily losses be justified? ”

Because they are opportunity costs and the people bearing the costs are largely the ‘rump’ who would benefit from the expansion. The “if we give them more you’ll have less” implication is very seductive.

“which suggests that unemployment may result in limited access to supportive re- sources, thereby increasing the impact of stressful events and then suicide risk.”

You could argue that’s the plan. In a market with too many people and not enough jobs the free market approach is quite ambivalent as to whether you grow the jobs or eliminate the people.

After all its not that far from the “treat ’em mean to keep ’em keen” attitude.

As I’ve been saying lately, microeconomic arguments are powerful political arguments. How does one fight against them?

What else I notice is many discussing these issues that are non-academics do not fully grasp the concept of an automatic stabilizer. They think something like the JG is great during the downturn/GFC but should be completely abolished in the upswing. In theory it can be if private spending is sufficient as Bill recently blogged, but without the JG there is always likely to be some involuntarily unemployed.

You could argue that’s the plan. In a market with too many people and not enough jobs the free market approach is quite ambivalent as to whether you grow the jobs or eliminate the people.

I think that is a very important insight Neil. Some seem to be of the opinion that as jobs are lost, the natural entrepreneurial and creatively destructive forces of capitalism will generate new jobs in a reasonable time frame to sop up this newly available low-cost labor. But I don’t see why that should be the case, especially since these workers are usually lost “from the bottom”. Sometimes, the market economy simply downsizes and jettisons labor resources who are then more-or-less permanently excluded from the economy.

@Neil, Senexx, Bill, etc.

The problem I heard is thus:

If you make it easier to fire, more people will get hired because the companies which are wanting to invest in the economy don’t want to take the risks of a bad deal, so if they can cut jobs in the future if things go wrong, they will hire them now. The other implication is that if a company can only survive by cutting some employees, you’ll be saving jobs.

How do I reply to this? It doesn’t make any sense if you consider the overall scenario (if you make firing people easier, more people will be employed) but put it in these terms, it does make some sense.

@Talvez

But to put the opposite view – have you ever heard a company say that they will turn down orders because they don’t want to run the risk of employing people and not being able to fire them? Business hires to complete the work available.

Of course they would have some kind of business plan that projects orders and employment into the future, and might ask for overtime to cover short-term high demand. But would they, in that plan, actually cut employment because of the future risk? Only in the fantasies of the CBI – who are rhetorically in favour of hire-and-fire as it makes their life easy.

They have better ways to manage that risk, through contract hire and outsourcing.

@Talvez…

If you consider the overall scenario of companies firing people to survive, then you end up with less people employed overall, which means less people able to purchase the goods and services still being produced, which means companies sell even less, which means they need to fire more people. Repeat until there is nobody left to be fired.

It’s what people using fancy words call a “fallacy of composition”. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fallacy_of_composition

The best way to take away the risks of a bad deal for employers is to ensure that the economy is growing and that there is enough demand for their products/services.

It seems to me that there’s another perhaps simpler argument for direct government job creation, and one that might appeal to those of right wing sentiments; namely, “If you break something, it’s your responsibility to fix it,” and, “The government did it.” It goes like this:

When we look at primitive barter economies, we find zero unemployment, which suggests that the real natural rate of unemployment is zero. This in turn suggests that it is the introduction of a fiat that actually creates unemployment. No fiat, no unemployment. Of course, it is the government that creates the fiat, and thus it is the government that creates unemployment. The government has therefore “broken” something, and thus has the responsibility to fix it.

Now, the government has many tools to promote private sector employment, and since a robust private sector is desirable, it should certainly use those tools as well as it is able. Still, no use of these tools in any combination in the past has ever returned us to the real natural rate of unemployment (i.e., zero). It is therefore the government’s responsibility to hire anyone who cannot otherwise find employment, even as it seeks ways to promote employment in the private sector.

“I hope everyone gets 5/5 so I can stop writing them.”

You’ve got 2 chances and I just saw Slim walking out the door.

End of the week and I’ve had a couple.

Just wanted to say

I still lurve the USA

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1dC0DseCyYE&feature=related

While some of the benefits of work you mention, sometimes, for some people, do apply, let’s not get carried away. They need to be balanced against the drawbacks:

– social exclusion and the loss of freedom: stuck with unpleasant coworkers and in commuting most of your waking time

– skill loss: being stuck in the wrong job (guaranteed or not) and losing touch with one’s calling

– psychological harm, including increased suicide rate: due to work-related stress, bullying by colleagues or managers, etc

– ill health and reduced life expectancy: staying on the sofa is much less risky than mining

– loss of motivation: you can get stuck in debilitating and repetitive routine because it pays the mortgage and lose all will to enjoy life

– the undermining of human relations and family life: workaholics who realise at their kid’s funeral they worked too much to learn to know them, no time left for developing meaningful a ex-work social life when work colleagues are not people you want to relate to.

– racial and gender inequality: being forced to work by white male protestant work ethic types imposing their “salvation through toil” outdated view on the world

– loss of social values and responsibility: debilitating corporate cubicle culture turning human beings into sub-larvae.

And it’d probably be worse in a job guarantee programme, whose logistics I fear would make many (most?) jobs worse than remaining outside of the economic sphere. Indeed, most of the benefits you claim for jobs in a job guarantee scheme would apply if they’re paid the same as unemployment (people who find benefits to being kept busy would opt in). Having differential wages between staying home and the guarantee means some people will be forced into soul-destroying dehumanising jobs just to get the money.

Bill,

Surely if unemployed then one option is to steal to achieve wants/needs.

I would suggest major increases in crime are likely in countries with high unemployment levels – I am reminded that Italy allowed many South American immigrants in the 70/80s but did not allow them to work legally – some became pickpockets in the major tourist areas of Rome etc. to survive.

Crime another cost of unemployment?

“It doesn’t make any sense if you consider the overall scenario (if you make firing people easier, more people will be employed) but put it in these terms, it does make some sense.”

One of the ways to making firing easier is to have a deep Job Guarantee programme. Then you don’t need to artificially incarcerate employees at their current employer – long after the relationship has broken down – just to avoid the stigma of a high unemployment rate and a drop in aggregate demand.

Which, paradoxically, will likely mean that more people will be employed by the private sector. It’s a bit like having a lower speed limit on a road which actually increases the overall throughput.

I’ve always been of the mind that employment protection should simply be determined as the amount of money you need to pay to get rid of somebody instantly. Because at the end of the day that’s what it always boils down to anyway.

“When we look at primitive barter economies, we find zero unemployment, which suggests that the real natural rate of unemployment is zero”

I suspect that is because primitive barter economies never get to the size where matching inefficiencies kick in.

Another case of correlation rather than causation.

If the Government had the political will, it could readily overcome the problem of persistently high unemployment

The problem is that (in the EZ at least) that the governments, elected or installed, implacably direct their will towards an unemployment policy. The hatred and contempt for their populations is tragically underestimated.

Neil Wilson’s first post has it succinctly, as evidenced by the moral freeloader norman lamont not so very long ago:

“Rising unemployment and the recession have been the price that we have had to pay to get inflation down. That price is well worth paying.”

just repalace inflation deficit to bring it bang up to date, humans in, metrics out.

Funnily enough, gormless norman ended up as current chairman of one of the EZ’s most unsavoury groups of like minded folk Le Cercle

re chrislongs

Entrepreneurial activity on the rise

A fifteen ton bridge , for goodness sake?

A perfect analogue of uk government policy

“Rising unemployment and the recession have been the price that we have had to pay to get inflation down. That price is well worth paying.”

Just replace inflation deficit to bring it bang up to date, humans in, metrics out.

That equals saying to a man: “We have good news and bad news. The good news is that prices didn’t rise. The bad news is that you don’t have a job anymore”

Good luck paying for the steady prices with declining income.

In previous blogs Bill has written on the JG, if you don’t like one JG job, you are free to take another one under the JG this counters the potential drawbacks listed.

Another bull’s eye hit on the target, Bill. Great post in light of the current kerfuffle over the MMT JG. I hope that the dissenters read it.

if anyone is sceptical about demand management, who is about to invade greeece?

Benedict, there is no such thing as a primitive barter economy. Nobody has ever found any evidence for a barter economy. But your point is absolutely right, comparing monetary and non- or pre-monetary economies. Attributing unemployment to the government intervention of creating a monetary economy, and concluding the state has the obvious responsibility to return unemployment to the natural rate of zero.

Bill and other MMTers point this out, but the point should be made clearer, simpler, more often and in as many ways as possible. It is not an “MMT dogma”, as I’ve seen it labelled. It is NOT “correlation not causation”, as I was surprised to see Neil say, but an absolutely fundamental point of MMT, functional finance, Keynes in his “Babylonian madness” mood & earlier thinkers.

Money is a creature of the state. The very purpose of introducing money into a non-monetary society is to CREATE unemployment, which is people who need/want jobs in order to get money, debts the state owes them, to pay debts toward the state. The more monetized the economy, the more necessary money is to live, the more pressing a problem unemployment is. Unemployment, by definition, is always and everywhere ultimately caused by the debts which are determined by the state, and payable only by means that the state accepts.

The only people who can give the unemployed jobs are people with money. And the only people with money are the people who got it from the state – the cronies. From this crucially important viewpoint, there is no such thing as “private sector employment” the way propagandists babble about. Everybody is a direct employee of the state, a crony, or an employee of a crony, etc. – an indirect employee of the state. The big difference is not between “capitalist” & “socialist” economies, but as Lerner and many others realized, between monetary & non-monetary economies. The issue of employment/unemployment is more fundamental than “capitalism”/”socialism” or “command”, and must be handled the same way in either case. Spend enough. The JG is the least amount of spending to ensure full employment. The least inflationary kind of spending possible.

That wealth in all societies goes to the cronies of the state is not a sad commentary on human corruption, but a truth of logic. Impeccable logician Willie Sutton robbed banks “because that is where the money is.” Bankers and crony capitalists (the nomenklatura, the apparatchiks becoming oligarchs) rob the state, because that is where the money is. There is always a “job” guarantee program for bankers & military contractors, and in general, rich people who get public money for usually insane & disgusting purposes.

A monetary economy without some kind of JG is a preposterous, absurd idea. No new money, no cronyism, no Cantillon effects, no tax or fee to drive the value of money, is clearly impossible. The JG answer is – everbody is a crony, at the least to the extent that they will get a living wage in return for their scarce, valuable labor, which will enrich all. A monetary economy without full employment, without a job guarantee is the state telling the unemployed that you owe the state debts, debts which you must incur to continue living. Debts that you could repay, but which the state refuses to allow you to repay, forcing you to be idle, for no reason at all. It’s the state declaring you its enemy. Small wonder that this is, and often should be reciprocated. The state does this because it is insane, having absorbed innumerate, illiterate, garbage “economics”.

In his Would the Job Guarantee be coercive? Bill mentions reciprocity, in connection with the idea that the unemployed should reciprocally do something for the state, for society, reciprocally, in return for their income, arguing for the JG over other forms of direct income provision. Reciprocity – if you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours is the foundation of non-monetary ( & even monetary) economies. But a more important and solid connection is that the JG itself is the reciprocity to the state’s demand for money made on those in need of the King’s coin in order to live, to pay the prices, for food or whatever, to the state or “the private sector”, which ultimately represent the state’s taxation & spending.

Not having full employment, effectively a JG (BSE) is “logically absurd” (cf Mosler , Exchange Rate Policy and Full Employment – I read his “nothing to do” as “everything to do” :-)) If ready, willing and able workers do not have a right to employment, then the word “right” has no meaning.

Bill or others,

What do you think of the potential for a “Zero Waste Jobs Program”:

The Ultimate Job Guarantee Implementation: Can we Achieve Zero Wasted Labor AND Zero Material Waste Simultaneously?!?

I realize this job role could be a possibility *within* any JG program already suggested by JG academics, but I wonder if explicitly dedicating a nationwide jobs program to this waste reduction goal could both make it more politically acceptable and incorporate significant additional benefits to society beyond the elimination of involuntary unemployment? Of course opinions may differ on how much a reduction in material waste flows would benefit society versus the work done by other types of previously proposed community JG work.

I did try some searches within academic MMT papers I could find and didn’t run into any direct references to this sort of thing (perhaps I didn’t try hard enough). So, does this idea seem promising, or am I overlooking or under-weighting any significant negatives?

By the way, here is a free version of Tobin’s paper that Bill quotes: Tobin, J. (1977) ‘How Dead is Keynes?’

@Some Guy

Thank you!

cig

«While some of the benefits of work you mention, sometimes, for some people, do apply, let’s not get carried away. They need to be balanced against the drawbacks:»

Your list seems an iteration of the problems raised by unemployment – for which there are studies pointing to those problems.

One problem : when has anyone ever made a command economy work?

Dear Lew

You asked:

What relevance has that comment to the post that you are commenting on? I never mentioned anything about a “command economy” – whatever that is!

best wishes

bill

What is a ‘Job Guarantee” program ? Someone in government determines what jobs are to be done, right? That is one variety of command economy.

You could have used the internet to look that up yourself, no need to be ignorant about what a command economy is. Wikipedia generally has good info.

Dear Lew Glendenning (at 2012/01/19 at 1:26)

Thanks for your comment.

You said:

To which I say, you haven’t read much of the JG literature. Often we say jobs should be determined “locally” to meet local unmet needs. The only “federal government” requirement is that they pay the bill and ensure the workers are hired at a fixed wage.

But of-course, under your definition of a “command economy”, most nations, including the US operate as command economies. The size and structure (what jobs are to be done!) of the US military is presumably determined by the government.

I never hear the almost visceral reaction to that sort of “government” job from those who seem to think the JG is some sort of socialist (command economy) nightmare.

best wishes

bill

bill,

Indeed, most countries are command economies under my definition. Have you noticed how all such countries are in their death throes? Due to deep structural problems in the politico-social-economic systems, they will all default on their national debts and many of their businesses and other institutions will not be able to stand without the government’s support. Many governments will be rebooted. Poor people are going to suffer, everywhere, as a result of the many policies Progressives, who have run almost all significant institutions in nearly every country for the last 50 years, and therefore deserve all of the credit, have instituted and which have consistently produced perverse outcomes.

I liked your other examples. Those socialist systems generally don’t work very well either. Our huge military is great at training, running bases, developing weapons, logistics, can move troops and equipment and tanks and ships and … anywhere, really fast, but it no longer can win wars, although it still presents a great image and so our less-acute Presidents keep believing in their invincibility and we keep starting wars — a typically perverse outcome of politically-driven programs. On purely practical grounds, one must oppose large militaries — they don’t scale well.

So now you have heard both. I guess you don’t talk to many Libertarians.

Lew

Lew Glendenning, a government is a religious enemy for you but a strategic friend to me. I do not see government as a competition. I elect government to fulfill the objectives I feel are important. In your world view no plan is good. However, too often than not a bad plan is better than no plan.

Btw I guess China falls under your definition of command economy as well. But it is hard to argue that it is on its death throes given that the Treasury Secretary and the whole eurozone are both busy securing money from China.

The lack of government leadership is the reason for the “all such countries are in their death throes”. Private sector is incapable of leading anybody to anywhere.

Sergei,

You really must study ‘self-organizing systems’.

You really must study mathematical chaos and computational complexity, understand how they limit anyone’s view of the future.

Without being able to predict any future (and if you could, you would be making so much $ you wouldn’t consider government ‘a strategic friend’), how do you navigate to a desired future.

Or, you could consider Godel’s Incompleteness Theorem, and how that dictates that no set of rules can be both complete and consistent. Gov runs on rules.

Or, you could consider all of the research showing that the standard controls of human behavior, incentives and rules, actually don’t work so well.

Finally, money buys power. A near-universal human flaw is that people serve their own interest before group interests. So they use anything they have to feather their own nests, e.g. the power of their job for governments.

All those are theoretical, which doesn’t mean they aren’t as inexorable as the theoretical gravity. But practically, you can’t point to any successful large government. They are all heavily in debt with declining economies and declining native populations. They will all go broke over the next few years, many will reboot.

So sorry, your views have been obsoleted by events.

Lew

Sergei,

I neglected to deal with your China example. Where to start …

First, China doesn’t have strong enough property rights to ever have a serious capitalist economy. Businesses are stolen by friends of the government quite frequently.

Second, China has a big problem with corruption, and 100s of 1000s of protests by their lower classes every year as a result. It isn’t stable socially.

Third, China now has as many workers as it will ever have, and thus has a seriously aging population. Combine this with more than 50M extra men, the future is neither bright nor happy.

Fourth, China is not buying more bonds, as it is spending $Ts to try to prop up is economy, which is in failure mode as a result of their cheap money, with the consequent bubbles. They have 65M unoccupied homes/apartments/condos, the prices of which are falling fast.

Fifth, Chinese banks are all completely bankrupt by Western standards. As China owns them, and can print $ to keep them from actually declaring that, China will have serious inflation. The inflation they have experienced so far is causing protests, more instability.

So China is far from an example of a successful, powerful-government country. There are no such examples.

Lew

Lew,

I usually avoid debates with the libertarians but this one might be interesting, I saw your profile on several websites.

1. What is a positive example of a country liberated from a government? Aren’t Somalia and some areas in Libya the closest to the ideal? I am not interested in theorising based on praxeology. Please give me an example of a modern society based on your principles and how it has out-competed its “powerful-government country” neighbours.

2. It seems that you don’t like government because of coercion. What about the coercion in the name of private property rights? Is it OK? To what extent? What about “intellectual property”? Can the informational content of your brain be my property? What about Big Pharma? Is their revenue-maximising behaviour moral?

Here in Australia we have an individual with a net wealth of $20 billion. She has property rights to iron ore deposits. These deposits were found on the land inhabited for at least 40000 years by the Aborigines. What is their net wealth? Where do they live? Is this fair?

If we don’t care whether something is fair or not and “a dog eats a dog” all the time, why do you hate corruption so much? Maybe corruption is a social phenomenon as natural as the emergence of the modern property rights.

Now regarding the points you have raised that:

1. “you could consider Godel’s Incompleteness Theorem, and how that dictates that no set of rules can be both complete and consistent. Gov runs on rules.”

2. “money buys power. A near-universal human flaw is that people serve their own interest before group interests. So they use anything they have to feather their own nests, e.g. the power of their job for governments”

Aren’t these 2 points mutually exclusive? So we have either have a rigid, rules-based bureaucratic system of power or we have a corrupt cleptocracy. A cleptocracy cannot run on rigid rules. Personally I would choose one line of attack instead of throwing everything at once.

Now regarding China. Sergey stated that “it is hard to argue that it is on its death throes” Your response is that “China doesn’t have strong enough property rights to ever have a serious capitalist economy.” So what? Maybe they don’t need these rubbish American property rights extended to anything anywhere. As someone wrote on Twitter, ”Under SOPA, you could get 5 years for uploading a Michael Jackson song. One year more than the doctor who killed him.”

You raised one more interesting point. “You really must study mathematical chaos and computational complexity, understand how they limit anyone’s view of the future. Without being able to predict any future (and if you could, you would be making so much $ you wouldn’t consider government ‘a strategic friend’), how do you navigate to a desired future.”

I may know something about these topics but I really don’t understand what chaos theory or computational complexity has to do with the idea of the government filling up the gap in aggregate demand caused by either debt deleveraging or private saving.

You may have purely chaotic movements of particles in gas but still the statistic laws of thermodynamics describe the system parameters on the macro scale. Quantum uncertainty rules in the microscale, you cannot even measure the location and momentum of an electron along the same axis with the accuracy better than determined by Heisenberg’s law – how could people have made transistors? You cannot control the behaviour of the individual wheat plants but you can fertilise the soil, grow wheat and harvest it.

Please be aware that command economy is not the same as state capitalism or mixed system where the government uses market forces to achieve certain social goals. I lived in a communist country and I can tell you the difference. We don’t have meat coupons here in Australia. You need to remember that Oskar Lange and J.M.Keynes were two different people. One cannot recycle the arguments from the debate about social calculation to criticise aggregate demand management using Functional Finance or programs like Job Guarantee.

Finally, if you think that a country X issuing it’s own currency, with a floating exchange rate and with no foreign denominated debt is “bankrupt” please read the “Debriefing 101” posts on the right-hand side panel of this blog.

Lew Glendenning:

All of private sector companies live by “command economies” definition. They run planning, they run budgets and they command internally. There is no self-organization. Government is the same but it has an extra ability to shape the system of rules plus issue money.

This world is driven by competition. At the very least it is a competition by countries which starts, despite the Olympic principle, with sports. This world is NOT a self-organizing system.

In chess there are 32 pieces which, if self-organized, will lose the battle in under ten turns. Centralized authority, the player, makes them fight and win. That is how China has become economy no.2 in short 20 years. You assume that your liberalized western metrics can measure other cultures as well. Sorry, but you do not go with your own tea to India. Besides that you forget that Western banks are probably as corrupt as Chinese and maybe even more. You forget that most of the developed world is seriously aging and imports great amounts of young labour force. And you forget that China is still buying bonds because it props its economy with yuan and is still a net exporter (which just shows that you do not understand it).

Finally, human beings are irrational and their behaviour is not subject to mathematical logic. However, above all mathematical logic and theory human beings have to comply with the second law of thermodynamics.

Government does not have to have THE complete view of the future. It does not need it. Government needs A vision of it. It can be a wrong vision, but, as I said before, in this world even a wrong vision can be better than no vision. Because what is wrong depends on what your competitors do. And if they have no vision at all, then a wrong vision can all of a sudden become the only (right) one.

I also find it quite funny that so many people bla-bla-bla about China however for all practical purposes the Chinese civilization is at least double the age of ours (white western). And China with its principles is still around however there is no guarantee whatsoever that our principles will make it into the next millennium.

Lew, there are no examples of successful countries without (sufficiently) powerful governments. Your comments are diametrically opposed to observable reality and common sense. I and many other here are sympathetic to many libertarian ideas. But many libertarians have ideas about economics which are nonsense. The same innumerate nonsense that is incessantly, mindlessly repeated by academia & the media, only made more extreme.

Which is a good thing – it is easier to refute purer, crazier, more extreme statements. Like the idea that there are any major advanced economies outside the Eurozone with any risk of default or serious inflation (except from oil prices, of course). And the ONLY reason that the Eurozone has a problem is that it institutionalized a monetary system based on impossible, insane economics, which had made European economies irrationally avoid spending & embrace unemployment, compared to the USA, even before they signed the Euro suicide pact.

But practically, you can’t point to any successful large government. They are all heavily in debt with declining economies and declining native populations.

Again, a bizarre contradiction of reality. Of course large governments are “heavily in debt”. This is a tautology. Being in debt is the primary economic function of a government. Government debt has a name. It is called “money”. (Often, “NFA” is used here). Saying that a government should have no debt equates to saying that its people should have no money. Chaos, complexity, godel are meaningless buzzwords here. MMT is about accounting & arithmetic. Try paying bills by incanting chaos, complexity, godel, rather than with a positive account balance in the King’s coin or equivalents. Doesn’t work.

Or, you could consider Godel’s Incompleteness Theorem, and how that dictates that no set of rules can be both complete and consistent. Gov runs on rules.

That’s wrong buddy, that’s not what the Theorem says. There are plenty of (simple) formal systems that are both complete and consistent.

Every economy is a command economy to some extent. And China has undeniably been a success in the last 30 years or so in improving the standard of life of hundreds of millions of people. Of course there is plenty to criticize about their model, politically as well as economically, but you can’t say it hasn’t been successful so far. But China is just catching up which is easy, they are basically copying everything they need. So that is the real limit to their growth, but there is still a long way to go until they do catch up, and by that time they might have learned enough to become really innovative and keep growing.

Don’t you think Singapur is a successful command economy?