I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Food speculation should be (mostly) banned

Last year, Cyclone Yasi wiped out about 75 per cent of national banana production in Australia and drove the price of bananas up to around $A15 to $A17 per kilo depending on where you lived. They are usually less than $A3-5 per kilo. But all banana lovers complained about the imposition on their real standard of living even though Australians allocate only 10 per cent of their total expenditure to food and, obviously, much less to banana consumption. So imagine what it is like for the most disadvantaged citizens to see prices rise by 60-odd percent over 18 months on their basic food stuffs, especially when they allocate upwards of 60-70 per cent of their total expenditure to food, and they spend all their meagre income? Not a good outcome that is for sure. While the financial market excesses caused the crisis in the first place, and the policy folly of our governments is prolonging it, one of the worst features of the neo-liberal years of financial deregulation has been the speculation on food which has driven prices up dramatically, impoverished and starved millions. Food speculation is something I would ban as part of a new oversight of the financial markets aimed at restoring the real economy and ensuring economic activity worked to improve the human condition.

Two valuable sources of data exist – the FAO Food Price Index and the The World Bank Food Price Watch.

The full FAO dataset is available HERE.

The following graph is borrowed from the FAO Food Price Index page and it shows the average food prices since 1990. The FAO say that the Index “is a measure of the monthly change in international prices of a basket of food commodities. It consists of the average of five commodity group price indices (representing 55 quotations), weighted with the average export shares of each of the groups for 2002-2004”.

The evidence is well documented. This recently released (January 2012) study – Farming Money – from Friends of the Earth Europe reports that:

Food prices … after a period of relative stability, increasing by an average 56% between January 2007 and June 2008.

The FAO Food Price Index from from 117.8 in January 2007 to 184.9 in June 2008.

Similarly, between December 2008 (FAO index number 122.1) and April 2011 (Index 206.6) the food price rise was 69.3 per cent.

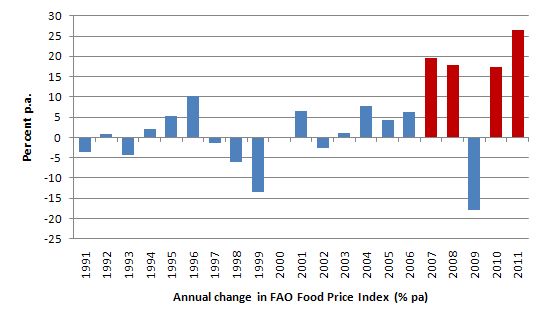

The next graph shows the annual percentage change in the FAO Food Price Index from 1991 to 2011. Clearly, the red columns stand out. So in 2007 the general index rose by 19.7 per cent, then 18 per cent in 2008, dropping by 18 per cent in 2009 as a result of the recession, and then rising 17.2 per cent in 2010 and accelerating by 26.5 per cent in 2011.

The graph hides the extent of movements in the specific components (the five commodity groups) with sugar being more volatile than the other components of the index.

The following graph is constructed using data available from the US Economic Research Services (attached to the Department of Agriculture). The ERS publishes very detailed data on country-by-country food spending proportions (of total expenditure). I used the data from Table 97. Expenditures spent on food and alcoholic beverages that were consumed at home, by selected countries, 2010 – DOWNLOAD HERE.

I apologise that the countries are hard to determine but if you double-click the graph you will see a much larger version.

The Asian Development Bank publication (April, 2008) – World Bank Food Price Watch Report (for February 2011) provided estimates of the poverty impacts of the food price rises in 2008:

Applying the population-weighted average increase in poverty to the total population in low- and middle-income countries, we infer that the recent rise in food prices may have put 44 million people into poverty in these countries. This reflects 68 million people who fell below the $1.25 poverty line and the 24 million net food producers who were able to escape extreme poverty.

Around this time last year (January 5, 2011 in fact) – the World Bank boss Robert Zoellick contributed a Financial Times article – Free markets can still feed the world – in which he praised the G20 Food Security initiative and implored them:

… not to prosecute or block markets, but to use them better. By empowering the poor, the G20 can take practical steps towards ensuring the availability of nutritious food …

The title was a mis-nomer given the agenda he outlined. I didn’t disagree with many of his proposals, which included:

Increase public access to information on the quality and quantity of grain stocks … Improve long-range weather forecasting and monitoring … Deepen our understanding of the relationship between international prices and local prices in poor countries … Establish small regional humanitarian reserves in disaster-prone, infrastructure-poor areas … Agree on a code of conduct to exempt humanitarian food aid from export bans … Ensure effective social safety nets … Give countries access to fast-disbursing support as an alternative to export bans or price fixing … Develop a robust menu of other risk management products … Help smallholder farmers become a bigger part of the solution to food security …

These “solutions” to the food crisis are all effectively non-market, state-sponsored interventions to redirect the food supply in one way or another.

Further, he failed entirely to outline the role that the financial markets are playing in intensifying the food crisis.

There has been considerable debate about this role with the mainstream view being that speculative behaviour is largely beneficial as a means of diversifying risk.

However, this September 2010 report – Food Commodities Speculation and Food Price Crises. Regulation to reduce the risks of price volatility – from the UN Special Rapporteur explicitly examined “the impact of speculation on the volatility of the prices of basic food commodities” and concluded that:

… there is a reason to believe that a significant role was played by the entry into markets for derivatives based on food commodities of large, powerful institutional investors such as hedge funds, pension funds and investment banks, all of which are generally unconcerned with agricultural market fundamentals.

The reference to agricultural market fundamentals relates to the traditional arguments justifying the efficiency of speculative behaviour. Accordingly, in mainstream financial economics textbooks (or agricultural economics books) you will read that speculation enhances the market fundamentals (demand and supply).

Futures markets developed to facilitate this sort of activity. A farmer who is to deliver a crop to a market at some future date will be unsure of the “spot” price at that date. All that he/she knows is that if the price is below some amount per unit they will lose.

The futures markets provides the farmer with a contract to supply a commodity at a given price at some future date. So if the break-even price is $5 per bushel and the future price is $5.50 per bushel then the farmer can be sure of a profit of $0.50 per bushel no matter what happens to the price over the course of the contract.

So the futures contract allows the farmer to hedge against the risk that prices will fall by the time the crop is harvested.

An “option” works in a similar way. The farmer buys a “put option” which might be to sell a volume at $5.50 per bushel at a given future date. If the price is below that when harvest day comes the farmer would exercise the option. But if the price was above the farmer would let the put option expire.

The counter-party to these contracts is the speculator. They are prepared in the case of a future contract to absorb the risk because they form the view that by the time the delivery is made the spot price will be above the agreed price in the contract. So by “insuring” the farmer against risk, the speculator expects to profit by on-selling the commodity to a food processing company.

There is a lot more to it than I have outlined but the general point is made.

As well as providing a hedge against risk to the “real” producer, the future contracts are said to help consolidate a fair price for the farmer. If the futures price rises, then the farmer knows that the expected spot price at the time they expect to bring their harvest to market will be rising and so it is a guide to what contracts they should enter.

In this way, speculation may improve the operation of the real sector.

The speculators will tend to buy low and sell high which reduces volitality and stabilises incomes in the sector.

That is the conventional view of the involvement of financial markets in the agricultural sector.

However, it is only a small part of the story. Speculators do not bring any new money into the sector – for investment in productive capital.

Moreover, some forms of speculation enhance price volatility. The Briefing Note says that “momemtum-based speculation” – in particular, “commodity indexes” – are destabilising:

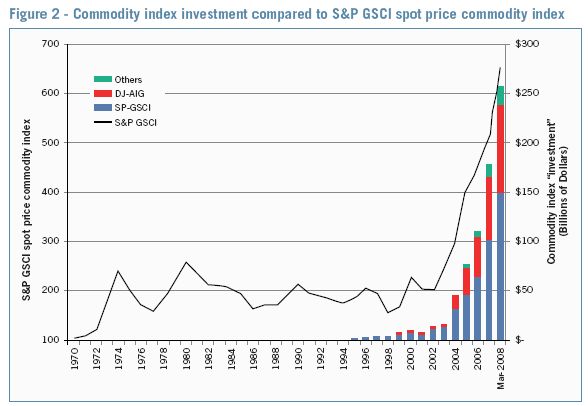

A commodity index … is a mathematical value largely based on the returns of a particular selection of commodity futures. The most famous of these is the S&P GSCI, formerly known as the Goldman Sachs Commodities Index, which was set up by Goldman Sachs in 1991. Others include the Dow Jones-AIG Index and the Rogers International Commodities Index. The composition of the basket of commodity futures varies according to the index, but agricultural commodities normally do not account for the majority of the commodities included in the “basket”.

The problem is index speculation generates a “vicious circle of prices spiraling upward: the increased prices for futures initially led to small price increases on spot markets; sellers delayed sales in anticipation of more price increases; and buyers increased their purchases to put in stock for fear of even greater future price increases”.

The following graph is taken from the Briefing Note but was sourced from a presentation that Jan Kregel gave in Chile in August 2008. Jan writes in the Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) tradition and was with the UNCTAD before moving to the Levy Institute.

It is a very stark graph and shows that as the “spot prices increased, this fed an increase in futures prices, which attracted even more speculation, thus setting the whole process into motion once again”.

The point is that index fund speculation is not remotely like the activities outlined above in relation to speculation improving market fundamentals and reducing risk.

As the Briefing Note says the “index speculator and the fund manager, far from being acquainted with crop production cycles and patterns, will never see a grain of wheat in their professional lives”.

The common link between “traditional speculator” and the “index speculator” is that both can create shortages of the commodity. The former by “hoarding the physical commodity” and the latter by “hoarding futures contracts”. The difference is that the latter is “spared the bother of maintaining a warehouse”!

The upshot is that both drive food prices up.

The UN Special Rapporteur’s Briefing Note (hereafter “the Briefing Note”) concluded that:

… closer examination reveals that the abovementioned arguments of supply and demand are insufficient to explain the full extent of the increases and volatility in food prices.

So underlying real shifts in supply and demand – the so-called market fundamentals – do not help us understand the huge food price spikes.

The Briefing Note also rejected the standard IMF line – for example, in this IMF publication – Impact of High Food and Fuel Prices on Developing Countries-Frequently Asked Questions – that:

… food price increases were the result of per capita income growth in China, India, and other emerging economies which fed demand for meat and related animal feeds such as grains, soybeans, and edible oils.

It is concluded that the IMF “interpretation is not corroborated by data collected by the FAO for the period concerned”.

The above-mentioned report – Farming Money – provides some new insights into the role of financial markets in the rising food prices.

They explore the role of “29 European banks, pension funds and insurance companies, including Barclays, RBS, HSBC, Deutsche Bank, Allianz, BNP Paribas, AXA, Generali, Allianz, Unicredit and Credit Agricole” and reveal “significant involvement of these financial institutions in food speculation, and the direct or indirect financing of land grabbing”.

They provide a detailed country-by-country analysis which I found very interesting and alarming.

They show that banks such as Barclays make “vast profits at the expense of the lives of the world’s most vulnerable people”. The substantive findings of their research are:

Among the European private financial institutions researched, it appears that the most significant actors involved in trading agricultural commodity futures, and other related derivatives and complex instruments, are Germany’s Deutsche Bank, UK’s Barclays, Dutch pension fund ABP, German financial services group Allianz and French banking group BNP Paribas.

Many financial institutions are involved in financing large agribusinesses whose activities entail purchasing or leasing land, including Dutch pension fund ABP, UK’s HSBC and RBS, Italy’s Unicredit and France’s AXA and Credit Agricole. Some of these have financed agribusinesses with explicit links to land grabs and human rights abuses, notably ABP in Mozambique, AXA in India and HSBC in Uganda.

A number of European private banks and insurance firms are directly involved in financing land deals that run the risk of land grabbing. Germany’s Allianz holds a quarter of a fund that invests in Bulgarian agricultural land, Deutsche Bank has invested in a fund that buys Brazilian farm land, and Italy’s Gruppo Assicurazioni Generali has a subsidiary that purchases land in Romania.

In these blogs – Operational design arising from modern monetary theory and Asset bubbles and the conduct of banks – I indicated that I would make illegal all speculative behaviour that was not directly related to improving market fundamentals.

The vast majority of financial transactions would fall into the non-productive category. Financial markets are the most unproductive of all activities in our economy.

So it would seem that this sort of financial activity would fit into the category that should be regulated out of existence.

The problem raised by those who recognise this damaging speculative behaviour is that if it is banned outright then the markets lose the “good” speculating (as noted above).

The Farming Money report offers some ways around this problem while still stamping out the “bad” speculative practices.

They are aware that “(a)lternative means to support agriculture other than hedging through commodity derivatives need to be promoted in order to meet the needs of farmers, food producers, processors and consumers, and to ensure stability in, and adequate finance of, the food supply system”.

To accommodate the two objectives – eliminating the destructive impact on food prices from speculation but still promote the market fundamentals – the Report recommends – among a wider range of options:

1. “Speculative trades that cannot be proven to serve the needs of sustainable development must be restricted”.

2. “… it is essential to reverse most of the de-regulation that has taken place over the last 20 or so years”. For example, “limiting positions held by speculators on commodity futures contracts, limits on daily price changes, and measures to deal with high volume and high frequency food commodity derivatives trading”.

So regulators might “(i)ntroduce strict position limits on the amount of the market that can be held by individual traders and by financial speculators as a whole”.

3. “Ban institutional investors and investment funds from food commodity derivatives” and “products like commodity index funds and exchange traded funds (commodity-ETFs) and notes (commodity-ETNs), as well as high frequency trading (HTF) should be prohibited in food commodity markets”.

4. Private financial institutions should “(l)iquidate all open positions and refrain from further activities in food commodity derivatives and related funds”. Further, “(b)anks and financial retail businesses should stop retailing financial products based on food commodities” and “Pension funds should refrain from controversial investments in the food sector”.

The Report provided other recommendations aimed at increasing transparency (bringing OTCs in regulated exchanges, for example).

I support most of the recommendations, although I would go one step further and actually ban anything that didn’t satisfy the recommendation (1) above and put the onus on the financial institution to demonstrate the case. I would also ban banks from any sort of activity in this context as per the blogs – Operational design arising from modern monetary theory and Asset bubbles and the conduct of banks.

In coming blogs I will write about how the balance between what should be banned and what can be allowed could work in an operational sense.

Conclusion

Until the general public realises that the vast majority of financial market activity is unproductive and in some cases highly damaging to the poorest people in the world (as in food price speculation) the regulators and legislators will find it difficult dealing with the problem.

Ultimately, the problem reflects a break-down of morality. It is clear to me that if everything was guided by a moral compass then no-one would seek to profit on food speculation at the cost of someone not being able to eat enough or feed their children adequately.

The logic of capitalism is amoral in that sense so regulation has to be introduced.

The legislative task is to keep the productive speculation while outlawing the rest. If successful, the financial sector would decline dramatically and productive investments would increase (chasing the capitalist return). The vast majority would be better off. The most disadvantaged might even get enough to eat.

Total Aside: Clarification

Apparently there have been some tweets from a US blogger who, in the past, has been writing Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)-derivative blogs, presumably based on the core material that has been developed in the blogs and elsewhere by the early group of contributors (Warren, Randy, Stephanie, Scott, and maybe myself).

The tweets intimate that this person has received nasty E-mail correspondence from “one of the head MMT honchos” and that “these people are so bitter” (apparently in relation to the recent Job Guarantee debate).

I have received several E-mails overnight (some just curious, others more antagonistic) asking whether I am directly involved in this matter (perhaps even the head MMT honcho!).

The answer is:

1. I have never met this person.

2. I do not know him/her.

3. I have never exchanged E-mails with them and certainly not in relation to the matters raised.

4. Which means I have not sent any nasty E-mails to him/her or anyone for that matter.

5. I have never mentioned this person in my work – academic or blog – by name or otherwise.

6. I never actually read the WWW site in question in any detail or frequency. I have viewed it as being derivative of our work and was happy that people were spreading the word. But other than that I haven’t attributed any importance to it.

7. I am not bitter about anything related to MMT or anything else for that matter.

I hope that clarifies the curiosity.

That is enough for today!

Great blog – favourited for future reference.

Bill, in regards to your “Total Aside: Clarification” response, you need to get hip with these sorts of internet exchanges. You could have simply replied in a singe tweet:

“Screenshot or it didn’t happen”

Also, you’re welcome. 😉

Thanks for the great article, Bill!

One of the most obscene “derivatives” of treating human food purely as a profit-generating commodity is its use as motor fuel. The term “biofuels” implies a gentle, scientific, benign, possibly eco-friendly product but, in reality, what little we’re saving in fossil fuels, we are paying many times over in human misery. Essentially, we are burning food so that we can move about! In the meantime, people all over the world are starving. Where’s the efficiency in that?

Dear Bill

Can’t a futures market exist without speculators? After all, buyers of farm products may also like a predictable price. For instance, a flour mill may want to contract in the beginning of the year for x tons of grain in the fall. Farmers would commit themselves to sell it at a certain price and the flour mill to buy it at that price. Such a futures market needs brokers but no specualtors. Acording to a recent article in Der Spiegel, actors in the futures markets for food were until recently mainly food producers or processors. It is when these markets were opned to speculators that the problems started.

Regards. James

Here is randy wray on commodities: http://www.benzinga.com/content/1954634/stresses-seen-at-the-outer-surface-of-the-ballooning-commodities-complex

Basically he says that law changes forced US pension funds to buy commodity futures to ‘diversify’, and since these pension funds are huge even allocating small percentage of their assets to commodities caused prices to go way up.

Vassilis, isn’t food production worldwide more than enough to feed everybody?

The main problem is distribution. I wouldn’t care much about biofuels, which serve some purpose, as long as there are plenty people living in the rich world throwing away a third of the food they buy, or getting obese, which serves no purpose.

Vassilis,

Just an FYI the leftover mash can still be used as a high protien feedstock (only sugars “removed”). Certain livestocks can consume this feed with no problems.

link_http://www.appropedia.org/Understanding_Ethanol_Fuel_Production_and_Use

“The non-fermentable solids in distilled mash (stillage) contain variable amounts of fiber and protein, depending on the feedstock. The liquid may also contain soluble protein and other nutrients. The recovery of the protein and other nutrients in stillage for use as livestock feed can be essential for economical ethanol fuel production. Protein content will vary with feedstock. Some grains (e.g., corn, barley) yield a solid by-product, distillers dried grains (DDG)–that ranges from 25 to 30 percent protein and makes an excellent feed for livestock. If the processing equipment is constructed of stainless steel and processing is carried out under well-controlled conditions, the protein by-products can also be consumed by humans.”

Resp,

Yes they do. They take it out again afterwards, but by then the farmers will have already benefitted from a better price for their crops, enabling them to grow more.

That’s the classic example of a market failure – but rather than the kneejerk reaction of ban it, why not try to make the market work? Any speculator smart enough to spot a rapidly rising price without a cut in production forecasts could easily make money with a call option or a futures contract to sell, which would also have the effect of smoothing out the market. And indeed farmers smart enough to see what’s coming could do the same.

The biggest problem with food futures isn’t that they exist, it’s that many small farmers never get the opportunity to trade them.

‘The biggest problem with food futures isn’t that they exist, it’s that many small farmers never get the opportunity to trade them.”

Oh, I’m sure there are some banks that would lend them funds for speculative activities.

How hard is it to open up an account and trade http://www.google.com/finance?q=NYSEARCA:GSG ?

There’s one thing about this that I don’t understand: as the futures contract expires, don’t the long speculators have to sell their positions, or be obligated to take delivery? And when they sell, why would that not drive the price down just as much as their buying drove the price up?

If the speculators, and not the supply and demand for, say, wheat, caused the price of wheat to be 600 instead of 200 (the numbers from the graph), how could the market clear, when real quantities supplied and demanded also adjusted to the new price? If farmers produced more wheat each year because the price was high and rising, and wheat users also demanded less because the price was high, then what happens to all that extra wheat?

Aidan, you miss the point. It’s not mainly about farmers, but consumers, who may starve due to these financial follies. Maybe, in the long run, we will all ride magical unicorns to “free market” utopia. But the problem is, as Harry Hopkins said: “People don’t eat in the long run. They eat every day.”

And even on the other end, because of the amount of money financial markets can and do gamble, the “smart enough” rational speculator or farmer could easily lose everything. Markets can remain irrational longer than they can remain solvent.

Bill’s recommendations are in fact proposals of how “to make the market work”, not kneejerk banning.

I don’t quite understand the mechanism which could make financial futures speculators “increase” food prices.

First, let’s call all future traders that do not buy/sell the real thing to match their future contracts holdings “financial” traders.

Part of the financials’ longs will be matched by financials’ shorts (short indices, dumb money arbitrageurs, etc). If they net exactly, there’s no problem. If the net position is net long, it takes two parties to trade a future contract, so 100% of this net financials’ long is matched by non-financials short, which by definition (as non-financials) buy the real thing to match their short futures and store it until the futures expires or the financials buy back their net long positions.

These guys, servicing the financials’ long, do increase the price but only temporarily, but as they sooner or later will need to sell, will then depress the price by exactly the same amount in reverse. This is unique to food which is perishable (unlike say metals). So across a full cycle the financials cannot have a price impact, because they can’t operationally change the supply/demand balance without touching the real thing.

You may get more random short term volatility, which is generally probably a bad thing, but this is a different claim and it’s sign neutral (the price pressure will be up as often as down during the full cycle).

To add to what cig said above, when I eyeball Fig 2 (assuming I am interpreting it correctly) I get the impression that futures prices are chasing the spot price up, rather than driving it.

There was a big debate started by Krugman on this wrt oil futures a few years ago. If futures market speculation is really capable of driving up the spot price, I’d like to understand the mechanism a bit better.

Since nobody really takes delivery on futures market bets, should be just a sideshow, right? For every long there is a short, and it all nets out to zero and the price for the real physical commodity is what it is regardless of what happens in this paper market. What am I missing?

«The problem is index speculation generates a “vicious circle of prices spiraling upward: the increased prices for futures initially led to small price increases on spot markets; sellers delayed sales in anticipation of more price increases; and buyers increased their purchases to put in stock for fear of even greater future price increases”.»

It looks like a bubble – just like housing.

I think everyone agrees that there is good and bad speculation and that regulation will have come in somewhere.

I leave below a couple of videos addresing this problem. The first one comes from a Indian Economist and the second one is a BBC HardTalk debate between an specualator and I think, the author of the report mentioned by bill. Worth watching both:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=344elODZbAY

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fFKD2yAYO4c

@John O’Connell:

For the market to “clear” and all contracts to be settled when the dates of physical delivery are near, everyone needs to find a counterpart, e.g. if you’re holding a contract obliging you to deliver on date D a Q quantity of product, you have to find someone willing to sell you a contract that forces its bearer to buy the same quantity on the same date. The paper trail begins by someone writing a contract by which he has no intention to physically abide.

@MamMoTh wrote:

“Isn’t food production worldwide more than enough to feed everybody?”

.

Irrespective of that, the fact remains that a significant number of people in the world are starving. (They are not pretending to starve.) Therefore, the effectively delivered quantity of food is not enough. What we’re doing by using food as biofuel is diverting a portion of the effectively distributable quantity of food into burning it up as motor fuel.

.

@MamMoTh wrote: “Biofuels…serve some purpose, as long as there are plenty people living in the rich world throwing away a third of the food they buy, or getting obese.”

.

Biofuels are not coming exclusively from thrown-away food. There are already fields dedicated to producing “biomass” (the organic material that’s mixed with fossil fuels to create “biofuels”). As to the real (health) issue of obesity in the western world, that’s obviously another symptom of the extreme social imbalances of our world. In any case, the issue of obesity is not going to go away by taking some food to use as motor oil, nor by increased demand making food more expensive: Odds are obese people will keep on being obese, while even more people will cross over to the camp of hunger, due to the higher prices. (This is already happening.)

.

@Matt Franko: Thanks.

Vassilis, I am well aware people are starving, that’s why there is a distribution problem with food production being sufficient to feed the world’s population.

I wouldn’t blame biofuels for that though. The fact is people in the rich world (and even the rich pockets in the poor countries) are overbuying food and then throwing it away unconsumed (I remember reading somewhere people throw away as much as a thrid of the food they buy), and overconsuming food and getting obese.

Options on agricultural commodities are what needs banning IMO. Options act in a non-linear way in relation to the underlying commodity. So they provide a bonanza for price manipulation. They make it well worth losing a certain amount by selling/buying the underlying commodity at a time when the market is illiquid and so easily flung about. So the major speculators loose money selling/buying wheat when the markets are quiet and then recoup and a lot more with profits made using their option positions. BUT even without options it is still possible to conduct a “Dr Evil strategy” by selling/buying at illiquid times to shift the price and then running with the momentum that creates, reversing the position when the market is more liquid.

I fail to see why higher food prices are harmful to the poor. They should benefit from higher food prices, regardless of the cause.

Higher food prices mean that farmers receive more revenue per bushel of product. It also means a transfer of wealth from non-farmers to farmers. Most citizens of poor countries are farmers. They produce food for their family, and any surplus that remains they may sell. Higher prices should make these citizens wealthier, as their surplus commands a higher price. Non-farmers and the unemployed would see the weath accumulating to farmers, and would seek to produce their own food to sell.

Admittedly there are problems associated with increased farming – soil erosion, loss of forestland, &c., but from an economic persepctive higher prices should benefit the poor.