The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

S&P ≠ ECB – the downgrades are largely irrelevant to the problem

The Australian Prime Minister, trailing hopelessly in the public opinion polls, made a fool of herself yesterday by commenting on last week’s S&P downgrade of European government debt ratings. she not only gave S&P more credibility than they are worth, but also demonstrated, once again, the mangled macroeconomic logic that is driving her own government’s obsessive pursuit of budget surpluses to our detriment. But there has been a lot of mangled logic about the S&P decision from a number of quarters in the last few days. Ultimately, the decision is only as relevant as the EU authorities allow it to be. The reality is that the fiscal capacity of the Eurozone is embedded in the ECB, which while ridiculous and reflecting the flawed design of the EMU, still means that the private bond markets can be dealt out of the game whenever the ECB desires it. In that context the S&P decision is irrelevant except for its political ramifications. And they arise as a result of the government’s own flawed rhetoric with respect to the role the ratings agencies play. That flawed rhetoric is exemplified by the Australian Prime Minister’s weekend offerings not to forget the French central bank governor’s recent claims that S&P should downgrade Britain’s debt ratings before it downgrades France. But does the downgrading matter? Answer: only if the ECB allows it to matter. The ratings agencies do not wield power. The issuer of the currency in any monetary union has the power – always.

First, lets deal with the Australian Prime Minister’s attempt to be relevant on the World stage.

The Sydney Morning Herald article (January 16, 2012) – Europe had it coming, says PM – reported that the Australian Prime Minister “rubbed salt into the wounds of European nations reeling from weekend credit downgrades, declaring they had it coming for avoiding tough decisions”.

Apparently, she said that the S&P decisions “were the ‘price to be paid’ by governments that had put off reforms”.

The SMH quoted the PM as saying:

For too many years, European governments have deferred the nation-building, productivity-enhancing reforms which Australia has made the foundation of our dynamic and resilient economy … In stark contrast to Europe … [Australia had strict fiscal rules that would return it to surplus in 2012-13. European leaders should] … swiftly undertake structural reforms to boost their economic potential and lift growth.

Note the text in square brackets was added by the journalists to link the two direct quotes.

These so-called reforms have left Australia struggling with employment growth barely able to keep pace with population growth; labour underutilisation rates of around 12 per cent; a vulnerable economy dependent on Chinese growth for our continued income growth; the East Coast economy where the vast majority of people leave in near recession; real wages lagging well behind productivity growth; and a degraded public infrastructure with under-funded public education and health, archaic public transport systems and more.

The reality is that the application of those “strict fiscal rules” is stifling growth in Australia and adding to the malaise noted above. it is highly likely that the negative impact on growth that is the direct result of the excessive pursuit of these fiscal will also undermine the government’s intention to record a budget surplus in 2012-13.

Further, “structural reforms” are not an appropriate response to a cyclical crisis because they take too long to implement and the realisation lags are long.

But the fact that she conceded them to be the appropriate response at this point in the crisis implies that she thinks the use of fiscal austerity in the face of a massive collapse in European growth is appropriate.

She quite clearly doesn’t grasp the basic macroeconomic rule and spending equals income equals output, which drives employment.

The SMH quoted a bank economist as saying:

Fiscal austerity leads to economic deterioration and budget deficits blown out. It has the effect of worsening the economic outlook.

Exactly!

The comments from the federal opposition were no better. The shadow treasurer was quoted in the article as saying:

She and her Treasurer have presided over a massive blowout in Australia’s debt and turned strong budget surpluses into record deficits.

He forgot to add that the “strong budget surpluses” were achieved as households built up record levels of indebtedness, which is now the reason private spending is currently flat. He also forgot to add that budget deficits saved the Australian economy from recession as world growth collapsed into crisis, which means that the loss in private income in Australia was far less than occurred, in relative terms, elsewhere in the world.

But what do the downgrades mean?

S&P outline their rationale in this document (published January 13, 2012) – Credit FAQ: Factors Behind Our Rating Actions On Eurozone Sovereign Governments.

It was also accompanied by the news release – Standard & Poor’s Takes Various Rating Actions On 16 Eurozone Sovereign Governments – which announced their decisions.

In the FAQ document they explain “What has prompted the downgrades”:

Today’s rating actions are primarily driven by our assessment that the policy initiatives that have been taken by European policymakers in recent weeks may be insufficient to fully address ongoing systemic stresses in the eurozone. In our view, these stresses include: (1)tightening credit conditions, (2) an increase in risk premiums for a widening group of eurozone issuers, (3) a simultaneous attempt to delever by governments and households, (4) weakening economic growth prospects, and (5) an open and prolonged dispute among European policymakers over the proper approach to address challenges.

We can agree mostly on those issues, except they do not mention that (1) and (2) are being solved by the actions of the ECB (its recent bank lending program and its Securities Markets Program (SMP).

They also could have mentioned that the “simultaneous attempt to delever by governments and households” and the inability of net exports to be strong enough to render that “simultaneous attempt” compatible makes it imperative that governments run larger fiscal deficits at this time.

They might also have mentioned that in doing so, the governments would be addressing (4) – “weakening economic growth prospects”.

They also noted that the political statements from the EU summit (December 9, 2011) would not lead to “sufficient additional resources or operational flexibility to bolster European rescue operations, or extend enough support for those eurozone sovereigns subjected to heightened market pressures”.

In other words, the EU leadership is lacking. While it might not be clear to everyone, S&P ratings are, in part, a reflection of their “political scoring” (“one of five key factors”) and they have been “adjusted downward” by S&P.

S&P claimed the the leadership is transfixed on the view that “the current financial turmoil stems primarily from fiscal profligacy at the periphery of the eurozone” while their view was that:

… a reform process based on a pillar of fiscal austerity alone risks becoming self-defeating, as domestic demand falls in line with consumers’ rising concerns about job security and disposable incomes, eroding national tax revenues.

Instead, they claim that the crisis stems from “external imbalances and divergences in competitiveness between the EMU’s core and the so-called ‘periphery'”

First, if there are structural issues that have to be addressed – for example, changing sectoral output composition, labour market re-skilling etc – then the most effective environment is one of economic growth. Resources move around the economy more quickly and smoothly when there is strong economic growth.

In a recessed environment resource reallocations are very difficult as new capital is slow to emerge and labour is highly immobile (hanging onto jobs etc).

Second, while the differences in unit labour costs (“competitiveness”) are obvious within the Eurozone they are only symptoms of the problem.

The underlying cause of the Eurozone crisis is the Euro itself. The fact that the member countries agreed to use a foreign currency (the Euro) and fixed their exchange rate, while ceding monetary policy decision-making to a “foreign” institution (the ECB) meant that their economies were vulnerable to an large demand shock.

This would not have been a problem had the original design of the European monetary system included a requisite supra-national fiscal authority capable of making spending transfers across the region in line with aggregate demand outcomes.

The Euro bosses deliberately decided to create a monetary union without such a supranational fiscal authority, and then made things worse, by imposing the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) onto member nations. This heightened the vulnerability of all member states to a large negative aggregate demand shock.

Within that structure, the costs of the aggregate demand failure were spread across the member states according to the regional pattern of the asymmetry of the shock. The so-called structural imbalances then made things worse.

Imposing fiscal austerity in such circumstances worsened the initial demand collapse.

So while S&P claim now that their decision reflects their view “that the effectiveness, stability, and predictability of European policymaking and political institutions have not been as strong as we believe are called for by the severity of a broadening and deepening financial crisis in the eurozone”, the reality is that the decision-making flaws go back to the inception of the monetary union.

The current political failure in the EU is just the latest manifestation of the capacity of the Euro leaders to work beyond their ideological (neo-liberal) biases and use government fiscal and monetary capacities to enhance the well-being of their citizens.

I agree with S&P about the “self-defeating” nature of fiscal austerity. The EU strategy is not only undermining growth but also worsening very targets that they claim justifies the austerity.

If you are intent on reducing the budget deficit relative to GDP then the most assured wide of achieving that way is to encourage economic growth, which boosts national tax revenues, and enhances private sector confidence.

In the current circumstances, with private sector deleveraging (that is, revising their previous spending decisions downwards), the best way to encourage growth is to expand net public spending (that is, increased budget deficits in a discretionary manner).

The failure of the EU political leadership is that it is imposing an ideological disdain for budget deficits onto the solution, which means that its solution guarantees failure.

S&P also identified as a risk factor the willingness of the European banks banks to continue funding member states:

In our view, it also remains to be seen whether European banks will indeed use the ample term funding provided by the ECB … to purchase newly issued sovereign bonds of governments under financial stress. We believe that as long as uncertainty about the bond buyers at primary auctions remains, the risk of a deepening of the crisis remains a real one. These risks could be exacerbated should renewed policy disagreements among European policymakers emerge or the Greek debt restructuring lead to an outcome that further discourages financial investors to add to their positions in peripheral sovereign securities.

It is true that under the monetary union the member states are financially constrained (as opposed to nations operating with fiat currencies) because they use a foreign currency that is issued by the ECB.

That means they require tax revenue and/or loans from the private sector in order to spend. If a member state exited the Eurozone they would immediately free themselves of that constraint and be free to spend whenever they liked. Fiat currency-issuing nations are not revenue-constrained in their spending and that means they are not at the best of the private bond markets.

Please read my blog – Who is in charge? – for more discussion on this point.

So it is a fair consideration to assess how robust the commitment of the public bond investors is to particular debt issues. The reality is that all Euro governments (Germany included) faces insolvency risk although the probability of that risk materialising varies greatly across the member states.

We know that Greece is already “insolvent” in terms of their capacity to access private funding for their public spending.

But where I think S&P is being gratuitous is in what they did not say. The ECB has currently decided not to let any member state become insolvent. Its Securities Markets Program (SMP) is ensuring that yields on precarious public debt issues (for example, Italy currently) are being kept down. The participants in the primary issuing market know that the ECB is operating rather vigorously in the secondary market.

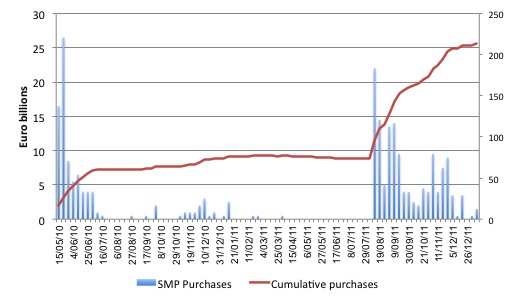

The SMP, which was established on May 14, 2010, means the ECB will purchase the bonds from governments which the bond markets will not lend to at reasonable rates at present.

Article 1 of the ECB Decision says:

Under the terms of this Decision, Eurosystem central banks may purchase the following: (a) on the secondary market, eligible marketable debt instruments issued by the central governments or public entities of the Member States whose currency is the euro; and (b) on the primary and secondary markets, eligible marketable debt instruments issued by private entities incorporated in the euro area.

You can read more recent information about the programme HERE.

As of January 9, 2012, the ECB has bought 213 billion euros worth of bonds under the programme.

The following graph shows the history of the SMP since May 2010 (up to the most weekly statement from ECB – January 9 2012). The bars shows the weekly purchases (or redemptions) while the blue line shows the cumulative asset holdings associated with the program (now at 183 billion Euros).

Clearly they accelerated at times when the private bond markets were withdrawing from tenders (as evidenced by the widening spreads of member state bonds against the bund). The SMP is unambiguously a fiscal bailout package which amounts to the central bank ensuring that governments can continue to function (albeit under the strain of austerity) rather than collapse into insolvency.

What does that all mean? Answer: a Eurozone government issues bonds to the private market who knows they can sell them to the ECB in the secondary markets and thus eliminate any carry risk. The ECB buys the bonds in the secondary market with euros which it creates as the monopoly issuer of the currency.

They then propose a tender to offer deposits with the ECB (with a ceiling of 1.25 per cent yield) up to the volume of outstanding SMP bond purchases. So they swap the euros for an interest earning account with the ECB instead of leaving the interest-earning bond in the hands of the private sector.

This swap is referred to as the sterilisation operation and allegedly “neutralizes” the bond purchases “by draining the same amount of money from the banking system”.

Please read my blogs – The ECB is a major reason the Euro crisis is deepening and Don’t tell the Germans – the ECB weekly deposit tender failed – for more discussion on this point.

So even if the authorised participants in the various member state bond auctions will not fund the governments at reasonably yields the ECB will not only ensure the funds are made available but also keep the yields down to whatever level it sees fit.

S&P do acknowledge that the ECB has been:

… instrumental in averting a collapse of market confidence. We see that the ECB has eased its eligibility criteria, allowing an ever-expanding pool of assets to be used as collateral for its funding operations, and has lowered the fixed rate on its main refinancing operation to 1%, an all-time low. Most importantly in our view, it has engaged in unprecedented repurchase operations for financial institutions.

The ECB will not allow any bank that is solvent go to the wall as a result of short-term liquidity issues. It will always make sure that the banks have enough reserves.

You might like to read this ECB document – The liquidity management of the ECB which describes the main financing operations (MRO) and the long-term refinancing operations (LTRO) – both supplying liquidity to the banking syustem on a regular basis.

MROS are “liquidity-providing, reverse operations with a maturity of two weeks, and they are executed once a week through a tender procedure” and provide upwards of 70 per cent of the liquidity needs of the financial institutions. The LTRO are “conducted once a month and have a maturity of three months”.

At present, these operations are providing billions of euros to the commercial banks.

S&Ps speculate that the ECB “has implicitly tried to encourage financial institutions to engage in a carry trade of borrowing up to three-year funds cheaply from the central bank and purchasing high-yielding government bonds”. But the point of these operations is to ensure the banks never run out of reserves to back commercial activity.

Then it is up to the banks to make loans and, capital-constraints aside, that capacity is dependent only on the willingness of credit-worthy borrowers to ask for loans. At present, that is not happening because private firms do not wish to expand investment while the economic outlook is so uncertain and rising unemployment is restricting consumption.

It all comes back to growth. Fiscal austerity is really stopping a number of mutually reinforcing actions from occurring which would, together go a long way towards solving the crisis.

S&P then discuss the ECBs SMP:

Reports indicate that many investors had hoped that a breakthrough at the December summit would have enticed the ECB to step up its direct government bond purchases in the secondary market through its Security Market Program (SMP). However, these hopes were quickly deflated as it became clearer that the ECB would prefer to provide banks with unlimited funding, partly with the expectation that those liquid funds in banks’ balance sheets would find their way into primary sovereign bond auctions.

But that hasn’t stopped the ECB expanding their SMP by some 6 billion Euros since the December summit. It is also clear that the ECB has the capacity to accelerate that program when things get really grim as we say in August 2011 (see above graph).

So I agree with S&P that “the ECB has not entirely closed the door to expanding its involvement in the sovereign bond market but remains reluctant to do so except in more dramatic circumstances”.

Bottom line: unless there is a political settlement reached whereby the Euro bosses allow one or more member states to default and/or exit the monetary union, the ECB will continue to stand guard and ensure that all governments remain solvent.

The question to ask though is why they are clearly just “marking time” – that is, keeping the ship afloat as it sinks. Why not embrace a pro-growth scenario – that has the best chance of ending the crisis – and announcing to the world that they (the ECB) will do whatever it takes to fund the resulting budget deficits for as long as it takes to grow the region out of the crisis?

S&P think that their:

… reluctance is likely prompted by concerns about moral hazard, the ECB’s own credibility (particularly should losses mount), and potential inflation pressures in the longer term. We think it may also be the case that the ECB (as well as some eurozone governments) is concerned that governments’ reform efforts would falter prematurely if market pressure subsides.

First, “losses” to the ECB are largely irrelevant. It cannot go bankrupt even if it became technically insolvent (in an accounting sense). Please read my blog – I wonder what Kepler 22b thinks – for more discussion on this point.

Second, there is no “long-term” inflation threat from the ECB purchasing government debt. Please read the following blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion.

The inflation threat comes from government spending (and all spending for that matter) and reflects the balance between nominal aggregate demand growth and the real capacity of the economy to absorb that growth. Building the central bank balance sheet is not the driving factor.

Third, whether there needs to be “structural” reform in any particular nation is a matter of opinion. Most of the structural reforms proposed by the Troika and related agencies (such as the OECD) are ideologically-biased against the workers. They make it easier for capital to impose harsh working conditions on the labour force at a time when unemployment is high, which weakens to the worker resistance to them.

But, as noted above, even if there was a need for such reform, the best time to encourage any kind of microeconomic resource reallocations is when the economy is growing not when it is being crucified by deliberately-imposed fiscal austerity.

Austerity encourages and creates sclerosis. Growth stimulates all sorts of upgrading effects including resource mobility and a willingness by different sectors to take risks and make changes.

Another interesting statement from the S&P FAQ was in relation to the narrow austerity focus of the December summit:

More fundamentally, we believe that the proposed measures … [fiscal austerity and tightening of the SGP] … do not directly address the core underlying factors that have contributed to the market stress. It is our view that the currently experienced financial stress does not in the first instance result from fiscal mismanagement. This to us is supported by the examples of Spain and Ireland, which ran an average fiscal deficit of 0.4% of GDP and a surplus of 1.6% of GDP, respectively, during the period 1999-2007 (versus a deficit of 2.3% of GDP in the case of Germany), while reducing significantly their public debt ratio during that period. The policies and rules agreed at the summit would not have indicated that the boom-time developments in those countries contained the seeds of the current market turmoil.

In this blog – The Eurozone failed from day one – I considered this issue in more detail.

The basic point is that the Spanish and Irish surpluses were a sign that the crisis was coming because they were driven by the unsustainable deficits in the private sector – particularly as a result of the credit-binge which drove the real estate markets.

So while you might look back and say that Spain and Ireland didn’t “mismanage” their fiscal policy choices, in a broader sense, these governments certainly failed, as did most of Europe and beyond, to appropriately regulate and maintain oversight of the out-of-control financial sector.

The more substantive point is that the tightening of the fiscal rules proposed at the December summit will fail because they will be breached each time a serious demand shock is encountered. The problem is that in trying to stick to these rules the member states will be scorching their economies and unnecessarily creating unemployment.

Also, ironically, they will be engaging in self-defeating behaviour given their aim is to reduce public deficits and debt ratios.

Please read my blog – It became necessary to destroy Europe to save it – for more discussion on this point.

Finally, S&P acknowledge that they:

… also placed a number of supranational entities on CreditWatch with negative implications. These included, among others, the European Financial Stability Fund (EFSF), the European Investment Bank (EIB), and the European Union’s own funding program.

Which means that the central planks of the Troika’s flawed bailout plans will be compromised.

The UK Guardian (January 12, 2012) article – Eurozone crisis: the key questions answered – provided some reasonable insights and says in this regard:

The eurozone’s rescue fund, the European financial stability facility (EFSF), uses guarantees from its member countries to raise funds in financial markets. If those backer countries are seen as less creditworthy, so is the fund – and it could well be downgraded too. That will make it more difficult and more expensive to raise money from financial markets and other countries outside the eurozone. The fund has already committed large sums to Greece, Ireland and Portugal and will need to raise more money should Italy and Spain need the same kind of help.

Again, the foundations of the “solution” imposed by the Euro bosses are all linked to the fatal flaw that the member states do not issue their own currency.

The whole system recurses back to that point. If they don’t issue their own currency they can never guarantee solvency for themselves or create the capacity to prevent the insolvency of other governments who share the same currency. They can also never guarantee their private banks.

This all points back to one thing – the big bazooka! The ECB.

Conclusion

So – does the S&P downgrades matter? Answer: only if the ECB allows them to matter.

As I have said often – the ECB could end the financial aspects of the crisis almost immediately by announcing they would fund member states for the duration – that is, until growth returned and the Euro bosses could decide whether they were going to really create a supra-national fiscal capacity (that is, not just impose harsher SGP rules) or voluntarily dissolve the failed experiment in an orderly manner.

The ratings agencies like to think that they have more power than they actually have. Their leash is only as long as the governments (that is, the currency issuer – which in the EMU is the ECB) allow it to be. Japan categorically proved that in the early 2000s as I explain in the following blogs – Ratings agencies and higher interest rates and Time to outlaw the credit rating agencies – for more discussion on this point.

That is enough for today!

” that is, keeping the ship afloat as it sinks.”

Interesting choice of analogy given the weekend’s events.

Certainly it shows that no matter how sexy and modern the owners think the ship is, when it sinks people die.

Problem is, no matter how much SMP the ECB does, unless they allow Governments to step in, things are getting worse.

First … The choice for voters in Australia is an unfortunate one … Which group of imbeciles can you possibly vote for when the time comes? However … I’ve always thought, no matter how big a dunce our Treasurer is, his greatest asset is Joe Hockey, a mental midget as mighty as they come. But Australians lose either way.

Second, all roads STILL lead to Germany. Those who think Bunds are a safe haven asset might be on the receiving end of a nasty surprise pretty soon.

I was blown away by this statement from the S&P:

“More fundamentally, we believe that the proposed measures … [fiscal austerity and tightening of the SGP] … do not directly address the core underlying factors that have contributed to the market stress.”

So can we conclude that Merkel, et al. aren’t reading the S&P’s statements about the ratings downgrade? Why are they continuing to push austerity when even (I assume) non-MMT economists are sayings that it won’t help anything? Wow, it almost seems like the EU leadership has an agenda…and it isn’t saving the economies of the member states.

Thanks for the post.

I well remember Tony Blair and Gordon Brown lecturing the rest of the EU – not about keeping your own currency which T.Blair never wanted to do any way – but about labour market and financial market deregulation and how that had created a British economic miracle. Beware the pride before the fall J. Gillard, and have you seen how much private sector debt and how big a property bubble we have here in Australia? It is (of course) private sector debt which creates financial fragility.

Ireland will collapse.

Debate on Irish State television tonight – they wish to close a regional train service opened as the bust was happening in 2010.

It is nearly empty although it travels between the third and fourth little cities in this bog.

It requires a 3 million a year subsidy now.

“Economists” (2) with a embarrassing shop keeping mentality talk about balancing the books……….. no MMTers of course or even close.

Not one mentions about the oil Import figures in Euro which could be the highest ever recorded in this state despite the fact the total BTUs burned has collapsed.

In 2008 we imported more petroleum and petroleum based products then food & live animals for the first time since at least the 70s

Oil imports : 4.913 Billion (Exports 757million)

Food imports : 4.681 Billion (Exports 7.08 Billion)

This situation reversed during the implosion of 2009 & 2010.

Well the trade stats for 2011 are indicating that oil imports will be higher then food imports again this year.

Road freight figures are truely astounding.

Road freight transport stats :

Year 1998 Year 2007 (peak)

tonne Kilometers (millions) : 8,184 18,707

Tonnes carried (thousands) :191,264 299,307

Vehicle kilometers (million) : 1,327 2,332

Average Number of vehicles : 50,033 97,752

Laden Journeys : 13,468 23,646

Year 2010

Tonne kilometers (millions) : 10,924

Tonnes carried (thousands) : 125,865

Vehicles kilometers (million) : 1,457

Average number of vehicles : 84,025

Laden journeys : 11,177

The Irish road construction has been a much bigger bubble then the Irish 19th century railways ever was.

I can only think of the halting of the Ballywilliam – New Ross mainline because of bankruptcy in 1864 (a branch line was later constructed) – when I think of the modern madness.

glasnost.itcarlow.ie/~feeleyjm/archaeology/bag-wex%20rail2.pdf

The irony now is the old railways are the only mechanism to save our market towns.

Why ?

Because the energy density is simply not there to link our towns with cars & trucks.

If we are to live withen our means via a new national currency the road network is toast as it was built primarily since we came out of the Sterling zone in 1979 (half optimized currency) into a pretend national currency whose objective was integration withen the European economic zone rather then a true sovergin currency.

It struck me the economists in Ireland have no concept of efficient resourse allocation withen a state economy – scary stuff really

Bill,

I completely agree about the S&P being a poor judge of credit-worthiness. They are controlled by the US government to a large extent, and by the investment banks to a very large extent.

However, even without the S&P, investors have to decide what stocks and bonds are worth investing in. At some point, it becomes obvious that the bond-holder cannot repay the loan, or the corporation goes broke. Or, that the government can never generate enough in taxes to pay the interest on their debt.

As these points approach, astute investors demand higher interest rates, which may well be the straw the breaks the caravan. Those points are noted by astute investors, with or without the ratings agencies. Indeed, as the ratings lag behind reality

The ECB will not be able to rescue both the banks and the nations from the consequences of huge debt without massive inflation. Massive inflation causes economic and social turmoil, often accompanied by political instability.

Europe is a group of failed nations. The ECB can’t rescue them all.

Lew

Seems a pretty well-balanced and temperate evaluation to me. In UK though eyebrows have been raised higher than yours by S & P having joined the growing chorus (from the right!) that “too much austerity is bad for you”. Now even Christine Lagarde has chimed-in. So why do the EZ honchos (as well as those nearer to home of course) continue to insist that the thumbscrews be further tightened. Sadism?

I think S & P got it about right:-

“We think it may also be the case that the ECB (as well as some eurozone governments) is concerned that governments’ reform efforts would falter prematurely if market pressure subsides” (Protection rackets only work if the target believes he’ll be screwed if he doesn’t play along).

– except they forgot to mention one other component in the mix:- electorates in those EZ countries who see themselves as footing the bill for the peripheral countries’ populations’ profligacy. This sentiment seems to have taken a firm hold on the public imagination (or anyway on a significant proportion of it). Example, a newly-elected Finnish government with a xenophobic anti-EU opposition breathing down its neck (the True Finns won the second-largest number of votes in the election, but is not in the governing coalition) feels compelled to posture as “tough” on Greek debt – so refused to sign-up to any further tranches of loans unless it (uniquely) was given collateral against its contribution.

Trust is in very short supply, but there’s a cultural gulf at the root of it.

In UK’s case it seems more than anything to be terror of losing its AAA rating, since all the forecasting arithmetic is based upon keeping it.

Lew: The ratings agencies ratings don’t lag behind reality. They have nothing to do with reality, and often “the market” Their main connection with reality is that the agencies are often bribed by real world criminals to give high ratings to worthless junk these con men peddle. Similarly, they downgrade the safest assets imaginable, like US or Japanese bonds. They are hardly controlled by the US government. Famously, these clowns rate Japanese government debt below Botswana’s.

Or, that the government can never generate enough in taxes to pay the interest on their debt. Governments with a normal, sensible monetary system like the USA, Japan, Australia do not use taxes to “pay for” their debt. That’s backwards. The private sector uses the government debt it holds to pay their taxes with. A dollar bill is an instrument of government debt. The ultimate use of dollars, which gives them value, is that they can be used to pay a debt, a tax, that the state levies on you. The US government has an infinite supply of dollars and treasury bonds it can issue.

The ECB could very easily rescue the whole Eurozone and immediately restore full employment, with no inflation. Unfortunately, the Euro institutionalizes innumerate, insane economics which makes such “rescues”, or central backing of the individual states’ debt, necessary. Such lunacies are the product of decades of garbage spewed into the media and academia, ever since the world simplified and improved their monetary systems to remove the last shred of truth from the predecessors of this trash. Paradoxically, the MMT point of view was essentially dominant before that. Basically, academic economics abandoned X-ray machines & anaesthesia and went back to leeches & exorcisms.

Europe is a group of failed nations. The ECB can’t rescue them all. Europe is a collection of very successful, rich nations, in many ways more successful than the USA. Their sole & unique problem is that they enslaved themselves to an entity run by maniacs or monsters, the ECB. They simply aren’t independent states any more – the Euro is rather worse than a gold standard.