The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

It became necessary to destroy Europe to save it

The message to be drawn from this blog is that the dithering Euro bosses have done it again. Amidst all the bluster about stability and moving forward together all they have done last week (at the EU Summit) was further undermine the prospects of their region. The new rules that have seemingly been agreed upon will not be achievable and will generate even more financial instability as growth deteriorates further. In early 1968, amidst all the lunacy of the Vietnam War, an American general told a New Zealand reporter that the US decision to bomb a town full of civilians into oblivion was based on the logic that “It became necessary to destroy the town to save it”. Last week’s (December 9, 2011) – Statement by the Euro area Heads of State or Government – invokes that sort of logic except in this case the brutality is of a different degree and style. Neither action was justified in the circumstances that the decision-makers faced.

This UK Guardian article (December 9, 2011) – As the dust settles, a cold new Europe with Germany in charge will emerge – said that the Statement of the EU leaders represented:

… the emergence for the first time of a cold new Europe in which Germany is the undisputed, pre-eminent power imposing a decade of austerity on the eurozone as the price for its propping up the currency.

The Monty Python script would say “who won the War”.

But the whole media discussion has failed to zero in on what a currency actually is and what it is for. “Propping up a currency” for what purpose?

The Germans seem to think that the only purpose is to satisfy the bond markets as does the British (for that matter).

From a Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) perspective, a currency is a vehicle that the issuing government uses to advance its socio-economic program after receiving a mandate via election. It is not a weapon that governments should use to undermine the prosperity of the people.

The EU leader’s Statement said that:

Today we agreed to move towards a stronger economic union. This implies action in two directions:

– a new fiscal compact and strengthened economic policy coordination;

– the development of our stabilisation tools to face short term challenges.

Which could in fact refer to a workable solution – the creation of a true federal fiscal authority which integrates with the central bank and to make major spending and taxing decisions at that level. Should the EMU wish to continue to issue debt (which I would advise against given there would be no reason to do so) they would have to issue at this level.

The ECB and the new federal government would be integrated to ensure that the currency issuing capacity served the fiscal mandate of the federal government. Clearly, the member states cede their fiscal authority to an elected federal government that represents all of Europe and membership is proportional to population.

I already covered some of the discussion in this blog – Tightening the SGP rules would deepen the crisis.

However, when you read on you realise that this is not at all what the Euro bosses envisage. They say:

The stability and integrity of the Economic and Monetary Union and of the European Union as a whole require the swift and vigorous implementation of the measures already agreed as well as further qualitative moves towards a genuine “fiscal stability union” in the euro area.

Now we are reading the language of Germany. If you go back to the mid-1990s, when the Stability and Growth Pact was being debated, the Germans demanded that it be a “stability pact”. It was the intervention of the French that saw growth added.

Now we read “a fiscal stability union” – yes, one that will find it very hard to grow.

The Statement outlined what this fiscal stability union would require in terms of a new fiscal rule:

– General government budgets shall be balanced or in surplus; this principle shall be deemed respected if, as a rule, the annual structural deficit does not exceed 0.5% of nominal GDP.

– Such a rule will also be introduced in Member States’ national legal systems at constitutional or equivalent level. The rule will contain an automatic correction mechanism that shall be triggered in the event of deviation. It will be defined by each Member State on the basis of principles proposed by the Commission. We recognise the jurisdiction of the Court of Justice to verify the transposition of this rule at national level.

– Member States shall converge towards their specific reference level, according to a calendar proposed by the Commission.

– Member States in Excessive Deficit Procedure shall submit to the Commission and the Council for endorsement, an economic partnership programme detailing the necessary structural reforms to ensure an effectively durable correction of excessive deficits. The implementation of the programme, and the yearly budgetary plans consistent with it, will be monitored by the Commission and the Council. A mechanism will be put in place for the ex ante reporting by Member States of their national debt issuance plans.

So member states effectively lose their democratic mandates and instead answer to the Euro bureaucracy and the ECJ.

While the new balanced budget rules will be bad enough, the increased vigilance of the so-called 1/20 rule will in my view be even more damaging to the growth prospects of the Eurozone and probably will be impossible to maintain.

In the blog – Tightening the SGP rules would deepen the crisis – I concentrated on the deficit rule and showed that the SGP was justified ex post based on computations that severely under-estimated the likely output gaps that the EMU nations might experience in a serious downturn.

The analysis at the time estimated that the average Output Gaps during recessions in the EU over the period 1975-97 was around 2.9 per cent. So a 3 per cent output gap was considered to be a severe recession.

In that blog, I showed that even when the output gap is below 3 (the OECD upper end for a safe budget outcome), the budget outcome is well above the Maastricht SGP and would warrant pro-cyclical fiscal policy being imposed (that is, austerity) and fines. Further, when the output gap is 3 per cent or close to it, there was significant violation of the SGP rules.

Moreover, even the cyclical swings in the budget outcomes during the current crisis have in many cases driven the budget outcome beyond the SGP rules.

In other words, the existing SGP criteria are already impossible to keep within during a significant downturn. And now the Euro bosses want to tighten them even further and invoke pro-cyclical fiscal reactions earlier.

While the budget rules are inoperative, the so-called 1/20 rule will be even worse. This rule says that EMU member states have to keep their gross public debt ratios below 60 per cent of GDP. If the ratio is above that level then the rule will require that the state has to reduce the gross debt ratio by 1/20 of the difference between the current level and the 60 per cent threshold – every year!

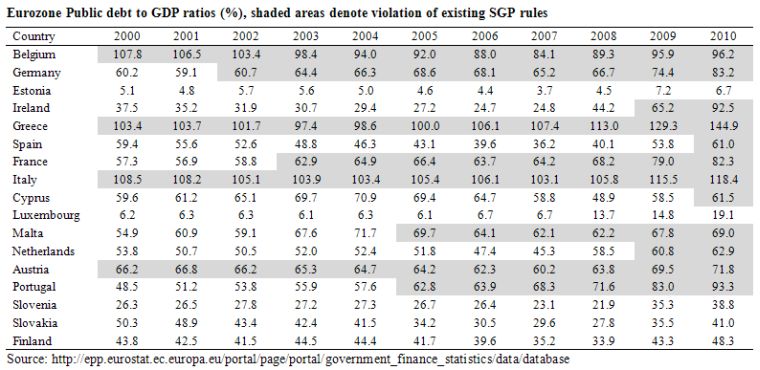

The following Table uses Eurostat government finance data and shows the public debt ratios as a percentage of GDP. As noted the shaded areas indicate violation of the SGP criteria and the 1/20 rule should be triggered.

The data shows you how far outside the rules most EMU nations are and in the many cases the violations are not just the result of the downturn. Nations have established public debt levels commensurate with their political-economic mandates and it would be hard to label the majority (if any) of these nations profligate or worse “out of control”.

Has anyone actually done some analysis of what shock to the budget that would require each year? I did a some casual analysis today to give readers some idea of how much the contraction in net public (discretionary) spending would have to be.

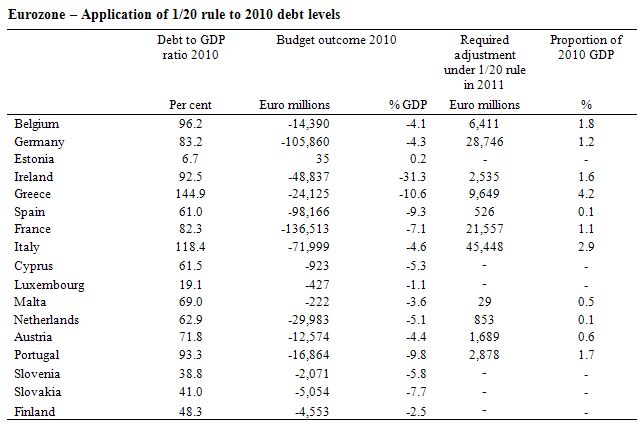

The following Table shows the results of the most cursory analysis. The second column shows the 2010 debt to GDP ratio (produced in the previous Table) for each Euro nation. The third and fourth columns show the current budget outcome (negative is deficit) in terms of percent of GDP and in millions of Euros.

The fifth column then shows what the application of the 1/20 rule would mean in 2011 (in millions of Euros) for each of the nations that exceed the 60 per cent rule. The final column expresses the 2011 adjustment in terms of the nation’s 2010 nominal GDP.

The analysis is a clearly far-fetched (underestimates the damage) because it assumes that from 2011 each nation is producing a combination of growth and primary budget balance (in addition to the nominal interest rate and inflation rate) to ensure the 2010 debt ratio doesn’t rise!

So with real growth likely to be close to negative in most of these nation and real interest rates close to zero or slightly negative, all the adjustment to “stabilise” the debt ratio would have to fall onto the primary budget balance.

If you think about the 2010 budget deficits (shown in Columns 2 and 3) and add what would be required to get not only a budget balance but also satisfy the 1/20 rule you start to encounter impossible numbers even if the adjustment was staggered over some years.

For example, the move back to surplus will kill growth for some years and may not even be achievable in the limits of social stability. The public debt ratios are likely to rise for some years until growth is robust enough. With pro-cyclical fiscal rules being imposed there is no prospect of growth in the foreseeable future.

In which case the adjustment imposed under the 1/20 rule would be even more harsh than my simple calculations would suggest.

I could also simulate various (feasible) growth, interest rate and inflation scenarios for each of the nations and what that exercise would show was that the primary budget surpluses that would be required under the 1/20 rule would be impossible to achieve and that the process of trying would take years and undermine growth for the decade ahead.

Was the UK Prime Minister exercising sound judgement?

Answer: definitely but probably for all the wrong reasons.

The UK Guardian (December 9, 2011) – The two-speed Europe is here, with UK alone in the slow lane – claimed (consistent with the title) that:

The result is that Europe is advancing towards its integrated destiny, with Britain in its rear-view mirror. The two-speed Europe has arrived, with Britain in a slow lane of one. Whatever the letter of the rules, the reality is that big decisions affecting Britain’s economy will now be taken in rooms in which Britain is not present and has no say. Soon, foreign-owned banks may wonder what sense it makes to be based in London, out on the margins. Cameron and his party are toasting what feels like a victory. In time, it may come to taste like defeat.

First, I think Cameron’s claims that he was protecting the “City” (Britain’s financial sector) were spurious. The Europeans can still damage the City if they choose to take on banks and reduce speculative behaviour. I hope they do. The “City” needs to be reduced in size and recognise that banking is a public-private partnership and should work to advance public purpose not line the pockets of a few but socialise any losses.

So if foreign banks migrate out of London, the British population should applaud that move.

Second, there is absolutely no reason why Britain should now be in the “slow lane”. The Europeans “integrated destiny” will be one of slow growth, persistently high unemployment, reduced social protections and generally pretty miserable.

It is often forgotten that the EMU has endured high unemployment for years now as the neo-liberal policy dominance developed. But during the last few decades the unemployed, while denied the benefits of work (income, social inclusion, etc) have been supported by a strong welfare safety net.

The future for Europe under these new fiscal rules and on-going austerity is that the unemployed will rise in numbers but the social protections will decline significantly. A bad combination to be sure.

The only reason Britain will follow the EMU nations down the slow lane if it maintains its ridiculous austerity drive – which is needless given that it has currency sovereignty.

So the on-going malaise in Britain will be entirely self-induced – by poor economic decision-making – and be quite separate from what is happening (or going to happen) in Europe.

Britain is not dependent on Europe for its prosperity.

So while the UK Prime Minister made the correct decision not to sign up for the European fiscal rules his own version of austerity is at present probably more damaging to his own population.

The New York Times article (December 10, 2011) – Euro Crisis Pits Germany and U.S. in Tactical Fight – made an interesting and valid point when comparing the attitudes of the Germans vis-a-vis the Americans. It is equally applicable to a comparison between the EMU nations and Britain.

The article said:

At the heart of the debate is the question of how far governments must bend to the power of markets. Mr. Obama sees retaining the stability of markets and the confidence of investors as a primary goal of government and a prerequisite for achieving any major changes in public policy. Mrs. Merkel views the financial industry with profound skepticism and argues, in almost moralistic fashion, that real change is impossible unless lenders and borrowers pay a high price for their mistakes.

Neither side of this “debate” is doing much about the “banks” etc no matter how much morality or lack of it is abroad.

But the irony of the statement is that the US has the power to deal with the “markets” being fully sovereign in their own currency while the Eurozone nations have only an ad hoc means – the reluctant ECB.

So the financial market sycophant (the US) won’t take on the might of the markets when they can, and the Europeans will find it much more difficult to deal the markets out of the picture.

There’s a short-term crisis that has to be resolved,” he said, “to make sure that markets have confidence that Europe stands behind the euro.

The NYT’s article also said that:

Strong governments can borrow cheaply, mainstream economists on both sides of the Atlantic argue, and have an obligation to intervene more aggressively than they would in normal times to make up for the slump in private demand.

But fails to mention that sovereign governments do not need to “borrow” at all and that means the US rather than Eurozone governments.

That doesn’t mean that Eurozone governments cannot intervene aggressively to make up for the slump in private demand. It just means they need the help and cooperation from the ECB.

In the end, both the Eurozone and the US have currency issuing capacity and should use it to fill the spending gap. The Euro crisis in the short-term is completely the work of the politicians and the central bank who refuse to take the necessary steps to address the problem – a lack of aggregate demand (spending).

The “sovereign debt” crisis in Europe is a misnomer. That manifestation is a crisis of leadership and cooperation (between the politicians and the ECB). Yes, it does go back to the flawed design of the monetary union, but even given that poor decision-making earlier, they still have the capacity to stop the “crisis” in its tracks within about 24 hours and to start repairing the real damage the poor leadership has caused.

Conclusion

Meanwhile back in the real world, the ECB continues its weekly SMP purchases of government debt which effectively holds the bond markets at bay and keeps the system from collapsing. At the same time, the ECB bosses deny they have any responsibility to fix the problem. But then they announce at the end of the each week how much more debt they are holding under the SMP and we know otherwise.

Future generations will be told “It became necessary to destroy Europe to save it” although what ends up in the “saved” form will not be what the children might have expected their parents would bequeath them.

That is enough for today!

When in a hole the first thing to do is stop digging.Apparently the Germans have still not learnt that lesson after 100 years of catastrophic mistakes.

Mistake (1) WW 1

Mistake (2) WW 2

Mistake (3) Scrapping nuclear electricity generation in favour of unreliable solar and wind with the lions share of electricity provided by coal and gas.

Mistake (4) Still thinking they can impose their will on Europe,this time by economic means.

Isn’t the plan to impose these rules on the 26 nations of the EU, rather than just the 17 currently in the Eurozone. What impact are the rules going to have on the other 9?

“But fails to mention that sovereign governments do not need to “borrow” at all”

And even if you want to pretend that they do, they all receive the income from the central bank. Some own the central bank outright. Therefore the only rational place that a government should borrow from is the central bank, since any interest charged by the central bank comes back to the government as a bank dividend – ie the cost of ‘borrowing’ is effectively zero anyway.

We should make more of that. It makes no rational sense for the government to ‘borrow’ from anywhere other than its own bank if you want to pretend that they have to borrow.

Looks to me like a plan designed to avoid a war. Instead of the Germans demanding borrowers go into deep recession and the Germans getting the blame for the forced misery the Germans and any nation or institution (ECB) who wants to avoid a war forming can fund the IMF to do the dirty job for them. It’s the IMF who will soon be demanding massive job losses in return for rescue funds. The public will vent against the IMF and in doing so avoid a war, but not the personal misery of job loss for millions of innocents.

Mate if this is rubbish just delete it. Its just the way it looks to me.

Cheers Punchy

Professor Mitchell,

Your table on debt/GDP ratios shows clearly that, with the exception of Greece (recognised as exceptional in the EU Commission statement), the ratios increased significantly for most countries since the peak of the 2007/08 GFC that was in the making since 2005 (see ECB announcement). There is also some evidence that debt/GDP ratios were managed down (eg Belgium) despite the GFC and many others kept their debt/GDP ratio from growing steadily prior to the GFC.

You seem to focus on traditional ‘aggregate demand managment’ as a ‘solution’ to unemployment. Unemployment is recognised to be a severe problem in some segments of the Spanish economy, in Ireland, in Greece and also in the former East Germany. Surely, the location and industry specific variation in unemployment indicates that ‘aggregate demand management’ isn’t quite sufficient to address the problems everywhere.

‘Aggregate demand’ management in general. During the period referred to as ‘the great moderation’ by some authors, ‘aggregate demand management’ was left to the proverbial Wall Street bankers (I say proverbial because not all significant players have their headquarter in N.Y.) and their partners, the rating agencies, in many regions of the ‘global economy’, but not uniformly. This system resulted in financial bubbles (1987, 2001, 2008 are the major events) and it culminated in a near total collapse of the international payment and financial market system. The GFC is still unwinding. For example, the French-Belgium bank Dexia is under financial distress not because of its buying of Greek public debt securities but rather due to its financial market gambles (derivatives and other complex securities).

In addition to the EU Commission statement of 9 December 2011, which you published, I understand there are also plans to introduce significant regulatory changes for the banking and finance sector of the Euro countries (awaiting the decisions of the parliaments of non-Euro EU countries to approve of their intensions to join).

Setting aside constitutional and other legal matters, are you sincerely suggesting the ECB should ‘print money’ to feed a totally undemocratic system where rating agencies dictate what governments have to do in the hope that unemployment might decrease in just the right locations and industries while ignoring the chance of yet a bigger financial bubble?

Fortunately, so far the EU population as well as their representatives don’t seem to be much impressed by attempts in some segments of the print and internet media to stir nationalistic sentiments. I hope it stays that way.

This will make your day. From the ECB on the negative impact of government size on economic growth.

http://www.ecb.int/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecbwp1399.pdf

@Neil “Isn’t the plan to impose these rules on the 26 nations of the EU, rather than just the 17 currently in the Eurozone.”

That’s what I thought, but I’ve not seen this stated explicitly anywhere. It would seem to be insanity to sign up to control over your debt/deficit if not part of the eurozone (or even if you were part of the eurozone). There’s been a lot of confusion in the media over the weekend between the EU and eurozone – at times just lumping them together. Not a good example of clarity. Either that or my brain is more addled than I thought.

I can appreciate what Ernestine Gross has to say.

Assuming her statements about some of the EMU countries’ response are accurate by the tables and other information, then yes, some of them have been making progress in their debt/GDP ratios. However, those ratios are actually irrelevant to the broken system in which they exist, in that if the ECB would simply act in a workable way those countries economies would be doing better.

It’s true, aggregate demand management would be a blunt instrument all on its own, if all it meant were indiscriminate spending by a federal government. Spending has to be coupled with careful guidance and external intelligence (information). And it won’t be perfect — the government doesn’t buy every kind of item the economy produces, so it will take some time for the economic benefit to diffuse into the remainder of the private sector.

I’m quite certain that Bill’s conception of aggregate demand management doesn’t include allowing the financial industry to run wild and hold the controls. The bubbles were the result of inadequate regulation of a highly unproductive industry that was way out of control. I imagine we all agree to some degree that financial deregulation is necessary.

Bill:

Per your comment: “So if foreign banks migrate out of London, the British population should applaud that move.”

We might want to extend one of the MMT insights: “exports of real goods are a cost, exports of financial institutions are a benefit”.

“Propping up a currency” = Fiddling.

Jobbik, Magyar Garda = Rome burning.

There is a reason Europe is a World War hatchery.

So has UK been Camerooned? If so then if Euro saved then banks move to Frankfurt and UK does not underwrite them – result for us UK taxpayers!

Euro zone fragments – Banks implode and even long suffering UK taxpayer unable to keep them afloat – a clear signal all is out in the open.

Understand Denmark still pegging currency to Euro, Poland Sweden claiming local votes needed to agree EZ rules.

When do Greek banks close for the holiday period ? so currency switch can go smoothly!

Bill, are you able to link me to a piece you did some time ago outlining the German employment assistance through the GFC? Tks in advance.

I’m guessing that a Tobin Tax could strongly affect the City of London, despite the veto, because all Euros are accounted for in the Eurozone (presumably in the National Central Banks) and therefore the tax could easily be applied at source to all transactions involving changes of ownership of Euro denominated assets. I doubt the UK could do anything about it.

@Ernestine Gross:

“are you sincerely suggesting the ECB should ‘print money’ to feed a totally undemocratic system where rating agencies dictate what governments have to do in the hope that unemployment might decrease in just the right locations and industries while ignoring the chance of yet a bigger financial bubble?”

No. Firstly, one of Bill’s main prescriptions is to stop issuing debt altogether. This would completely remove the ratings agencies from the picture. If you want to read what he thinks of them, have a look:

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=6857

Secondly, fiscal policy can target precise locations and industries, while monetary policy cannot – this is something Bill stresses time and time again. Here’s one of Bill’s posts dealing with evidence that fiscal policy works:

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=9932

apj

Maybe you are after this one on the Hartz “reforms”

Doomed from the start

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=7909

Graham Wrightson

From the comments section of an article on Britain’s place in Europe, rather good I think (the comment, that is, not the article, which can be read at: http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2011/dec/12/debt-crisis-europe-news)

EvilCapitalist

12 December 2011 10:55PM

Here’s a better quote, from an article written by Bernard Connolly written in 2002: (see the bits in bold)

“Within EMU, Ireland, Portugal and Finland have all gone through the up phase of a cycle generated by a discrepancy between the anticipated rate of return on capital and the ex ante real rate of interest. They are now clearly in the down phase of that cycle. In Ireland’s case, the boom was so fierce that cock-eyed optimists can contemplate a sharp fall in the growth rate as perfectly absorbable. But in none of these countries — with Greece to follow rather soon — will the process end with a nice, smooth return to a “sustainable” long-run growth rate. All of them will face depression, deflation and potential default. Public sector financial positions in all of them will deteriorate with amazing speed (in the “peripheral Europe” boom-bust cycle a decade ago, for instance, government borrowing as a percentage of GDP increased in several countries by more than a dozen percentage points of GDP in just three or four years), yet all of them begin with public sector debt ratios higher than was Argentina’s at the beginning of its recession. And the accession countries will assuredly follow a similar path when they join EMU.

Can the EU stand idly by and watch this happen? At first, yes. The ECB will claim that individual country developments are not its concern. And the EU as whole may argue that the countries concerned knew the rules, including the budgetary rules of the so-called Stability Pact: they have made their own beds, now they must lie on them. But that attitude cannot possibly persist. For however small these countries may be, financial markets will be aghast once the full horror of the slump, and it sociopolitical implications, becomes apparent. Ultimately, the ECB will be forced to behave as if it were the central bank of the small countries, easing monetary conditions massively depreciating the euro to keep the small countries afloat — at the expense of inflation elsewhere in the area — until a “political” solution can be arranged. What the politicians will decide will be to change the rules that currently prohibit EU bailouts of individual member countries. Bailouts will be instituted in return for the forced signature of the smaller countries on a new treaty which will extinguish what remains of national political independence in Europe. The progenitors of EMU knew exactly what they were doing. Thus Jacques Delors, for instance, said in 1995 that, “Monetary union means [our emphasis] that the Union acknowledges the debts of the member states of the monetary union”. The syntax is contorted,but the logic is clear: the “no bailout” provisions in the original EMU setup were a sham, designed merely to reassure the German public, which had always intuitively tended to believe that a monetary union without a political union must become a debt union. What would a European political union, necessary though not sufficient for superpower status, look like? It would certainly be plagued, as was the Austro-Hungarian empire, by a resurgence of nationalism. But things would be worse than that. For Europe is now multi-ethnic and multi-cultural. Such features have not been a problem-free even for the United States. But the United States has, at least in terms of its national myth, been a melting-pot in which races, languages, ethnic origins are fused in the pure flame of patriotism, a patriotism which is defined by allegiance to the constitution, to political institutions and political traditions. The American nation, that is, is a politically-defined nation. In Europe, it beggars belief to imagine that a politically-defined nation could be forged (although one should note, with horror, the recent press reports that five years ago the EU Commission wrote a secret paper arguing that political union would not come about without the perception of an external threat and that a terrorist outrage could contribute to producing such a perception). No, a political union in Europe would be created out of the deliberate destruction of existing politically-defined nations. And in that vacuum, populations would search for other sources of identity. It is all too clear that they would convince themselves, or be convinced by demagogues, that they had found their identity in terms of race, ethnic origin, language or religion. Europe would become a powder-keg of prejudices and hatreds. That is a horrifying prospect.”

That’s great, thanks graham. Appreciate you taking the time. There was something else (maybe I didn’t even read it here, though I think I did) about a specific job support subsidy a few years back, which was why the German u-rate wasn’t suffering as some thought it might theough the GFC … I’ll have a go finding it myself when i get some time.

Dear APJ (at 2011/12/14 at 7:34)

I think the blog you were referring to was this one Shorter hours or layoffs?

best wishes

bill

Dear APJ (at 2011/12/14 at 7:34)

I think the blog y

Tks mate, was just thinking about the issue when reading some recent research about the German labour Market and whether it can expect another labour market miracle a la 08/09.

@Grigory Graborenko

I am not sure “Bill” would agree with you. Be it as it may, your comment “No. Firstly, one of Bill’s main prescriptions is to stop issuing debt altogether. This would completely remove the ratings agencies from the picture. ” calls for a reply.

Firstly, who is supposed to not issue debt altogether?

Second, assuming you meant ‘the government’ (ie no sovereign debt) then, contrary to your assertion, rating agencies will will not be ‘completely removed from the picture’. May I remind that it was privately generated debt, rated by rating agencies as investment grade bonds instead of junk bonds (payoff characteristics like equity), which was a major factor in the onset of the GFC. To prevent a total collapse of the international payment system and the collapse of plain vanilla debt and equity markets, the USA and the UK and, to a lesser extent other national governments converted the private debt into public debt – at least major parcels of it.

Third, assuming you meant private and public debt, then you obviously failed to provide even a logical argument (a mechanism such as outlawing rating agencies) to make sense.

Fourth, how are you going to achieve zero private debt? May I point out that buying on credit involves debt. Depositing cash with a bank involves debt (for the bank).

Fifth, sovereign debt securities are an important form of financial contract which relatively risk averse people can buy if they want to save for a rainy day in the future, assuming governments at least attempt to contribute to maintaining purchasing power of their currencies.

It would be helpful if all ‘theorists’ – modern or otherwise – would start from the assumption that other people are at least as smart as they are and can observe events at least as well as they can. Think about it.

“Fifth, sovereign debt securities are an important form of financial contract which relatively risk averse people can buy if they want to save for a rainy day in the future, assuming governments at least attempt to contribute to maintaining purchasing power of their currencies.”

Not they are not.

Sovereign debt securities are almost exclusively used as trading chips on the global casino. They should be eliminated.

If the government wants to provide savings accounts outside private banks where people can ‘bail’ their cash then they can do so in the form of National Savings Accounts – with or without interest as policy dictates.

If government wants to provide a stready stream of income for pensioners in the form of a pension annuity then the private pension companies can hand over the loot in exchange for one and the government can pay the pension directly on top of any standard state pension.

Neil Wilson,

“Sovereign debt securities are almost exclusively used as trading chips on the global casino. They should be eliminated”

This is how the world of finance may look to you where you are during a particular time period and specific location where the term ‘trading chip’ is a meaningful short hand. If you want to say more than that, I’d appreciate if you could provide empirical data, by country, and preferably for a time series that covers the major institutional changes that took place since the late 1970s at various times in various countries.

“If the government wants to provide savings accounts outside private banks where people can ‘bail’ their cash then they can do so in the form of National Savings Accounts – with or without interest as policy dictates”.

Interesting. And what, I ask, is the unspecified provider of ‘national savings accounts’ going to do with the cash that has been “bailed” with them? Wouldn’t it be easier for governments to to issue savings bonds to the public? (Some countries have never stopped doing it and, at least one of them didn’t need bailing out by any agency nor print money).

Regrettably, the reality of the institutional changes since the 1970s, including ‘workplace agreements’, Hartz I, II, III, driven by naive market economics (including textbook HR experts), have resulted in a complex chaotic system which verbal theoreticians are unlikely to solve.

So I believe, the “MMT” ‘school of thought’ has the heart in the right place but, subject to evidence to the contrary – which I do not rule out – lacks theoretical rigour.

Incidentially, the Peter Hartz, a promoter of the Hartz labour market reform,, was a Human Resource Executive at Volkswagen before he became ‘adviser to the German government’. He was convicted in 2007. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peter_Hartz

“I’d appreciate if you could provide empirical data, by country”

The U.S. Federal government suspended issuing the well-known 30-year Treasury bonds (often called long-bonds) for a four and a half year period starting October 31, 2001 and concluding February 2006.[7] As the U.S. government used its budget surpluses to pay down the Federal debt in the late 1990s,[8] the 10-year Treasury note began to replace the 30-year Treasury bond as the general, most-followed metric of the U.S. bond market. However, because of demand from pension funds and large, long-term institutional investors, along with a need to diversify the Treasury’s liabilities – and also because the flatter yield curve meant that the opportunity cost of selling long-dated debt had dropped – the 30-year Treasury bond was re-introduced in February 2006 and is now issued quarterly.[9] This brought the U.S. in line with Japan and European governments issuing longer-dated maturities amid growing global demand from pension funds.

http_http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Treasury_security

Similar things occurred in other places

“And what, I ask, is the unspecified provider of ‘national savings accounts’ going to do with the cash that has been “bailed” with them?”

The unspecified provider is the government. We have it here in the UK. And therefore the money disappears in a puff of accounting logic once it has been bailed, only to reappear again when the person wants to draw it back. All by the magic of the currency issuer’s power.

The difference with government bonds is that savings account are not tradeable, and therefore not leverageable and they are only available to natural persons.

Providing accounts directly with the fiat provider gives individuals a safe storage option outside the private banking system.

Further to Sergie’s exposition, it is the managers of pension funds who have a demand for rating agencies because, in contrast to individuals who can make their own risk assessment, the movers and shakers in the ‘globalised financial system’, the managers of pension funds, are merely agents, privatised bureaucrats so to speak, who must not substitute their own risk preferences for those of their principals but must be seen to be ‘objective’. And so we get the corporatist version of a ‘market economy’, one characteristic of which, I venture to say, is false objectivity. It is false objectivity in the sense that people talk about ‘market pressure’ and ‘market prices’ while the actual institutional environment has little, if anything to do with the notion of ‘a market’. And all this is only a piece in the evolving mosaic of sloppy theorising that was at one stage advertised in Australia as ‘economic rationalism’. Quite made, really.

Yes, Neil Wilson, a ‘national savings account’ is not tradeable (in some countries there are also government issued debt securities that are not tradeable, eg Germany).

No, Neil Wilson, a ‘national savings account’ does not “Providing accounts directly with the fiat provider gives individuals a safe storage option outside the private banking system.” in any sense other than government guaranteed bank deposits or putting cash under the bed. For example, a person can put ‘savings’ (ie cash income not spent) into a national savings account for say 10 years with the aim of saving up for a large deposit on a house (or appartment). During this time the financial sector generates ‘money’ (debt denominated in national currency units) which finances a real estate bubble. That is, the rate of increase in house prices is much higher than the interest paid on the national savings account. As a consequence, the purchasing power of the saver’s deposits is systematically reduced. I would not call this “save storage”

“That is, the rate of increase in house prices is much higher than the interest paid on the national savings account. As a consequence, the purchasing power of the saver’s deposits is systematically reduced. I would not call this “save storage””

There is no natural law that states that you should have the same real purchasing power from nominal storage when you extract those funds as you did originally.

And as MMT shows it is perfectly possible, and sustainable, for the state to compensate people for their failure to manage inflation properly if that is seen as reasonable from a policy perspective.

So I will state it again: sovereign debt securities are almost exclusively used as trading chips on the global casino. They should be eliminated.

Neil Wilson, you have now convinced me that I have wasted my time. Have a Merry Christmas.