The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

The Eurozone failed from day one

The current Eurozone crisis is getting worse and has concentrated our minds on the most recent period of European history. As in all these situations where focus is very immediate our memories get a little blurred and we are inclined to accept propositions that closer analysis of the data suggest do not hold water. January 1 was the tenth anniversary of the date when Euro notes and coins began to circulate. It had of-course been operating since January 1, 1999 but only in a non-physical form (electronic transfers etc). If you believe the rhetoric from the Euro bosses in the first several years of the Euro history and didn’t know anything else you would be excused for thinking that it was a spectacular success. The Celtic Tiger, the Spanish miracle, the unprecedented price stability and all the rest of it. But the reality is a little different to the hype. The fact is that the common currency did not deliver the dividends that were expected or touted by the leaders leading up to the crisis. All the so-called gains that the pro-Euro lobby claim were in actual fact a sign of the failure of the design of the union although it took the crisis to expose these terminal weaknesses for all to see. My view is that the Euro was failing from day one and it would be better to disband it as a failed experiment that has caused untold damage to the human dimension.

In the special 10th Anniversary of the ECB edition of the ECB Monthly Bulletin – there is a lot of self-congratulation about the achievements of the ECB in its first decade of operation.

The then ECB President, Jean-Claude Trichet also gave a speech in Munich (July 10, 2008) – The euro’s 10th anniversary: history and presence of the euro – which traversed the same ground.

One notable statement in this Speech was:

The achievements I have just described have accompanied an impressive performance in terms of job creation. From the start of EMU to the end of last year, as I have already mentioned, the number of people in employment in the euro area has increased by 15.7 million, compared with an increase of only some 5 million in the previous nine years, and the euro area unemployment rate has fallen to its lowest level since the early 1980s.

While on the surface that sounds like a good achievement the devil is in the detail. Were there that many jobs created? In which countries were they created? In which sectors were they created.

Eurostat publish a very useful annual macroeconomic database called – AMECO – which I use often. While an annual database makes it difficult to examine cyclical turning points and the like it is helpful in providing longer-term insights.

But in terms of those questions, the AMECO database provides some of the answers.

This theme was also covered in an interesting article in the UK Guardian (January 1, 2012) – An unhappy anniversary for the euro – by one John Grahl.

John Grahl says that:

Trichet claimed at the same time that monetary union had been good for employment: “Between the launch of the euro and the end of 2007, the euro area created more than 15 million new jobs and the unemployment rate was at its lowest level since the early 1980s.” In fact the European commission’s Ameco database now gives the growth of employment in the original eurozone (the first eleven countries plus Greece) between 1999 and 2007 as 13.7 million. But, of this total, two thirds, or 8.9 million, took place in the “periphery” – in Ireland, Greece, Spain, Italy and Portugal.

So off to AMECO we go to check up on all of this.

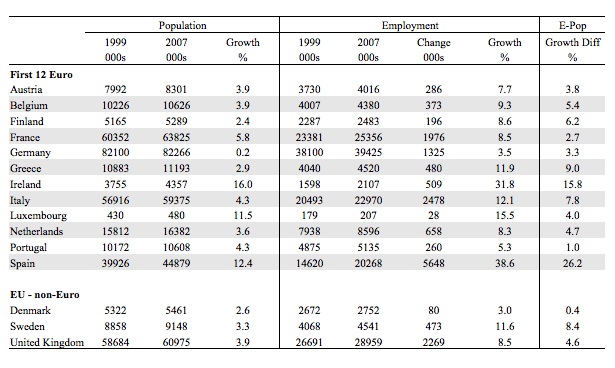

The first table summarises the main employment aggregates for 1999 and 2007 (that is, the period that Trichet is referring to above) and adds information on population to provide some idea of scale.

The nations shown are the original Euro nations plus Greece who entered two years later in 2001. You can see that the strongest employment growth was in the so-called peripheral Euro nations (barring Luxembourg). While we cannot use the AMECO database to

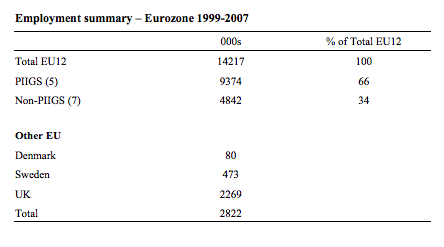

The second table provides a different summary of this data by aggregating the employment changes in the EU12 by PIIGS (5 nations) and non-PIIGS (7 nations). It is this decomposition that puts the first decade of the Eurozone in context.

As you can see there were actually 14.2 million jobs created in net terms between 1999 and 2007. The former ECB boss was thus exaggerating by about 11 per cent.

Note I use the term “net terms” to make it clear that in fact there would have been many millions more jobs actually created over this time period just as there would have been millions of jobs destroyed. There is a difference between considering the gross flows of job creation and destruction (which is a daily process) and the net changes assessed at two points in time.

As John Grahl says 66 per cent of these jobs (9374 thousand) were created in net terms in the nations we now deride as the PIIGS. The Non-PIIGS nations accounted for the remaining 34 per cent of the EU12 job creation in net terms (4842 jobs).

Three other EU nations (Denmark, Sweden and the UK) created 2.8 million jobs in net terms alone and if we add those to the EU12 total then these three non Euro nations would have generated 16.6 per cent of the total jobs.

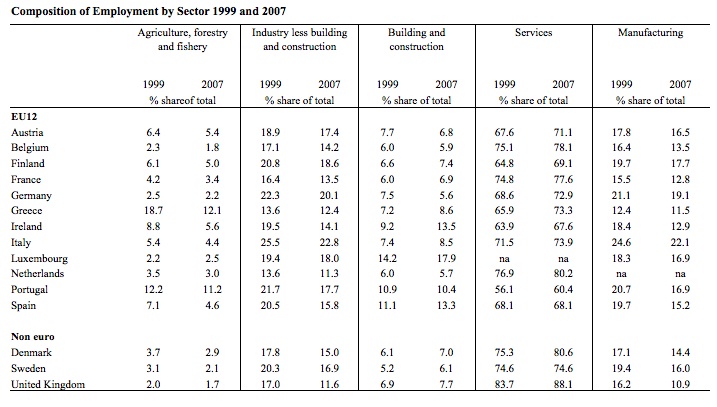

The following table provides some clue at the sectoral level as to what was going on in the first 10 years of the Eurozone.

It shows employment shares (as a proportion of total for each country) by broad industry sectors (at the lowest disaggregation available in AMECO).

You can see that the substantial increase in the Building and Construction sector share in Ireland and Spain which was associated with its housing boom.

The same sort of increase did not occur in Greece, Italy nor Portugal. The services sector in those nations were the standout employers but that was not a trend that was exclusive to them.

What conclusions might we draw from the employment data?

John Grahl correctly states that:

In other words, the growth of employment was not due to the good functioning of the monetary union but to its malfunctions. It depended on widening trade imbalances – huge surpluses in Germany and some of its neighbours against widening deficits in the periphery, covered by unsustainable capital flows from the former to the latter. Even so the employment performance of the eurozone was not such an impressive achievement. What Trichet called the lowest level of unemployment “since the early 1980s” was still, in 2007, before the global crisis pushed it back up, 7.6%. In the three countries which chose not to adopt the euro, Denmark, Sweden and the UK it stood at 3.8%, 6.1% and 6.6% respectively.

The other valid point that John Grahl notes is that the Eurozone experiment should be appraised not only between 1999 and 2007 (which was the period that Trichet was claiming to be a great success) but also in the 20 years prior to 1999.

I noted in a blog last week that the father of the NAIRU concept Franco Modigliani considered the restrictive macroeconomic policies that European governments employed in the 1980s and 1990s were damaging and misguided. In 2000 (‘Europe’s Economic Problems’, Carpe Oeconomiam Papers in Economics, 3rd Monetary and Finance Lecture, Freiburg, April 6) he said:

Unemployment is primarily due to lack of aggregate demand. This is mainly the outcome of erroneous macroeconomic policies… [the decisions of Central Banks] … inspired by an obsessive fear of inflation, … coupled with a benign neglect for unemployment … have resulted in systematically over tight monetary policy decisions, apparently based on an objectionable use of the so-called NAIRU approach. The contractive effects of these policies have been reinforced by common, very tight fiscal policies (emphasis in original)

The European governments initially became obsessed with culling inflation from the system in the 1980s and then after the Maastricht Treaty in the early 1990s they continued the relative austerity to ensure they could meet the entry criteria.

As a consequence, John Grahl says that:

Candidate members for monetary union sacrificed development and employment to come into compliance with the Maastricht conditions, later perpetuated as the stability and growth pact.

So for 30 years or more, the European governments, in particular the Eurozone member states have been deliberately deflating their economies in search of their dream of monetary union.

The consequences are now dire and to continue this vandalism, the Euro elites are now attacking the democratic basis of the governmental system. They have deliberately ignored the preferences of the people in the individual nations and when a head of state has looked like deviating from the Troika-mantra they have been replaced by a non-elected technocrat with pro-Euro, pro-ECB, pro-IMF sympathies.

As John Grahl says:

… if the monetary union does survive, in the form now planned by EU leaders, then the cure could turn out to be worse than the disease.

He is referring to the so-called “fiscal union” which he says “does not involve a genuine co-ordination of macroeconomic policies or significant transfers of tax revenues”. He correctly views it as an “authoritarian structure that would subject the weaker states to permanent and extremely intrusive surveillance, formally by the commission and the ECB, in reality by Germany and the stronger northern European states”.

The very states that relied on the so-called profligate peripheral Euro states for the miserly employment growth they generated between 1999 and 2007. Without Greece and Spain and the rest of the now vilified PIIGS spending the non-PIIGS would have looked very ordinary indeed in terms of their economic aggregates.

While Germany is being held out as the example for all to follow, John Grahl notes that:

One alarming aspect of German views of the current “reforms” is a fascination with numerical limits – on public spending, on public borrowing and so on. In many ways these are analogous to the Friedmanite notion of numerical limits on the money stock and, just like money supply rules, they will prove to be either ineffective or dysfunctional. Public debt is not a control variable available to policymakers; it represents a relationship between the public sector and the unstable, unpredictable, private sector which does not admit of mechanical arithmetic constraints.

Yes, the obsession with ratios. It is correct to point out that these ratios are not “control variables”. As I have noted in the past, budget balances, for example (and hence shifts in public debt) are driven by the state of the business cycle. The major fluctuations in economic activity occur due to the variability of private gross capital formation (investment).

Strong private spending growth leads to smaller budget deficits (relative to GDP), other things equal. A rising public debt ratio is typically a sign that private spending is weak.

The only problem is that in a fiat monetary system where the currency is issued by the elected national government and allowed to float freely on international markets, these ratios are largely irrelevant to the conduct of government.

But in the Eurozone they are not as a result of the flawed design that the Euro elites introduced from the outset. As John Grahl notes it would have been a totally different situation right now if the Eurozone was built with a federal-level fiscal institution that was charged with the “genuine co-ordination of macroeconomic policies or significant transfers of tax revenues”.

The elites refused to include that essential capacity because they were ideologically opposed to the use of fiscal policy and sought to impose the rigid Stability and Growth Pact rules on all member states.

Not only were these rules impossible to keep within (because budget balances are not control variables) but they biased the region to a low growth future even before the crisis.

The only strong employment growth – as we have seen – were in areas and sectors – that could not sustain that impetus.

The first major negative aggregate demand shock was like a breathe of wind against a house of cards.

Conclusion

To repeat – the first 10 years of the Eurozone were not as glowing as the official rhetoric might have led you to believe. Sure enough there was some strong employment growth regions and sectors but the composition of that employment growth was never sustainable.

The redistribution of employment towards construction in Ireland and Spain was unsustainable.

The reliance on growth in the peripheral states which helped Germany run strong current account surpluses was unsustainable.

In general, the Eurozone was failing from day one.

That is enough for today!

Bill, an insightful post as usual, and if I might I add: It’s quite short, too 😉

“The European governments initially became obsessed with culling inflation from the system in the 1980s and then after the Maastricht Treaty in the early 1990s they continued the relative austerity to ensure they could meet the entry criteria.”

To this I would add that at the time, monetary policy for all prospective EMU founding members was for all practical purposes controlled by the Bundesbank, which, as is well known, was far from enthusiastic about the whole project. (Otmar Issing spoke of the “spectre (Schreckgespenst) of a European Central Bank” – whose Chief Economist he later became.) Now, one of the entry criteria was that a country’s CPI inflation in 1998 must not deviate by more than 1.5 percentage points from the average of the three countries with the lowest inflation rates. You don’t need to be a conspiracy theorist to argue that this was a strong incentive for the Bundesbank to tighten monetary policy even further than they might have done in the face of very sluggish growth and record high unemployment in Germany following the post-reunification recession. Inflation came down from just over 4 percent in 1993 to 1,7 in 1995 and 0,9 in 1998, the year that counted. Other European central banks whose governments wanted to join EMU had no choice but to follow suit. The result was excessive monetary tightening on top of excessive fiscal tightening in Europe (minus the UK) pretty much throughout the entire 1990s.

One more thing: You have quoted from Modigliani (2000) repeatedly now. Let me point to a Solow paper (adapted from a speech given in front of a German audience) from the same year which struck the same chord: http://ideas.repec.org/p/ces/ceswps/_231.html

“Now I want to speak about the unspeakable: I am almost tempted to suggest that women and young people leave the room. The subject is one that, if it is mentioned at all in polite company, is grouped with witchcraft, drunkenness, and the abuse of children, things that we know are there but that are best denied. It is possible that one source of continued high unemployment in Europe is that the domestic demand for goods and services, and therefore for labor, has been forced to unnecessarily and unhealthily low levels?”

He has a biting critique of the Bundesbank’s output gap calculations in that one as well.

“They [the statistical procedures] are guaranteed either to smooth away any persistent difference between actual and potential output, or else to tell you that if output is below potential this year it must have been above potential last year or the year before. […] if I understand the Bundesbank’s method adequately, it is required always to make the average level of potential output during each four or five year period equal the average level of output actually observed during that same period. This means that the calculation can never conclude that there has been a persistent gap in either direction. This method is not confirming the dogma; it is part of the dogma. […] If this method had been applied in the 1930s, it would have reported a much smaller Depression […] In addition, it would have come to the truly remarkable conclusion that some of those long Depression years […] were actually years of excess demand and overemployment. The Bundesbank, if it had existed then, would have felt impelled to contract the already desperate economy, and the Sachverständigenrat would have agreed.”

Solows talk, incidentally, did have some effect: By 2003 the Bundesbank had revised its methodology, and in a monthly bulletin they calculated output gaps from 1973 and 2002 based on their new non-parametric methodology. Of those 30 years, they found the output gap had been positive (overutilization) in just seven. 23 (!) years were marked by – often massive – underutilization of resources, including the entire 1980s and all the 1990s starting in 1993. (You can see the graph here on p. 48: http://www.bundesbank.de/download/volkswirtschaft/monatsberichte/2003/200303mb.pdf). Needless to say that there is absolutely no recognition of inadequate monetary policy anywhere in that article. (It also does not identify the Solow rant as a motivation, but Okun’s Law, which he puts forward in his speech, makes an appearance.)

Best wishes

If you are talking history .. I think the German reunification had a large effect on germany, and the way germans think about how macroeconomy (should) work. It made for more austerity than germany had had before. After propping up east germany, germans are more afraid of having to prop up southern europe.

Happy New Year to all. Dr. Mitchell, please do not feel uniformly constrained to write short blogs. I did not finish even one cup of coffee while reading today’s lecture. I understand the time and effort it requires of you, but I, for one, thoroughly enjoy reading all you have to write. Cheers, Jim

This is unrelated to todays post from Bill, but it’s pretty funny. This is the single most true post Krugman has ever put up:

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/01/04/the-nonsense-problem/