The other day I was asked whether I was happy that the US President was…

Hungary helps to demonstrate MMT principles

I have received a lot of E-mails overnight about developments in Hungary. The vast majority of these E-mails have suggested that these developments (sharp rise in government bond yields since November) coupled with the fact that the Hungary uses its own currency (the forint) and floats in on international markets provide problems for the Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) understanding of the monetary system. I have been digging into the data on Hungary for some months now as I learn more about the history of the nation and its political and institutional structure. I am always cautious researching foreign-language material because outside of documents published in Dutch or French my comprehension skills are weak and I know that even in English documents there are tricks in trying to come to terms with the way data is collected, compiled and disseminated. However, unlike many non-English-speaking nations, access to very detailed data for Hungary in English is reasonable. I will have more to write about their problems in the future as I accumulate and process more information. But at present what I can say is that Hungary is a very good example of what a government with its own currency should not do and the current developments reinforce the insights available from MMT rather than present us with problems. Hungary is in deep trouble exactly because it has violated some of the basic macroeconomic principles defining sound fiscal and monetary policy.

This blog is not intended to be a definitive statement about Hungary. It reflects some of the products of an on-going research effort. But it should highlight some of the key MMT issues that the mainstream media is ignoring.

Some facts about the Hungarian monetary system:

1. The Hungarian currency the forint floats on international markets.

It hasn’t always done that. The Magyar Nemzet Bank (MNB) – the Hungarian central bank – reports that:

Pursuant to Act LVIII of 2001 on the Magyar Nemzeti Bank, the Government decides on the choice of exchange rate regime in agreement with the MNB. With effect from 26 February 2008, the forint exchange rate has been floating freely vis-à-vis the euro as a reference currency, with movements in the forint determined by the interaction between the forces of supply and demand.

In June 2001, the Hungarian government lifted all restrictions on citizens holding foreign currencies (see BBC report. While this allowed citizens to open foreign bank accounts etc it also marked the beginning of the private foreign-currency borrowing boom.

2. The forint is issued by the government under monopoly conditions – so it uses its own currency.

3 The central bank sets the policy interest rate.

These points would suggest that the currency is sovereign in MMT terms.

The problem is that there is one additional characteristic that is missing in the Hungarian case. The national government borrows heavily (and increasingly so) in foreign currencies. Once they do that their sovereignty is effectively lost and they become exposed to default risk on the foreign-currency debt.

But before I consider that in more detail lets see what the real economy has been doing. I note that unemployment is around 10 per cent at the moment although that is a serious underestimate given the extent of hidden unemployment. I will do a separate labour market analysis another day.

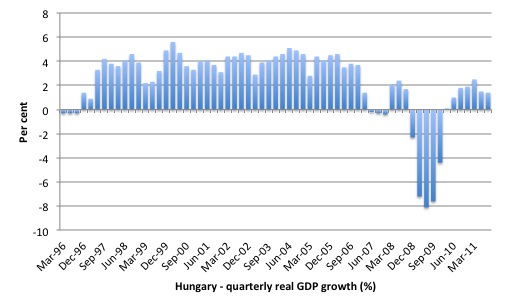

You can access national accounts data from the Hungarian Central Statistical Office. The following graph shows the quarterly growth in real GDP from March 1996 to September 2011.

The crisis was very damaging to national economic activity in Hungary. After a false start (a mild recession over three quarters from the June- to December-quarters 2007), real GDP growth collapsed in the March-quarter 2009 and plunged by 7.2 per cent, 8.1 per cent, 7.6 per cent, 4.4 percent over the next 5 quarters before resuming tepid growth in the March-2010 quarter.

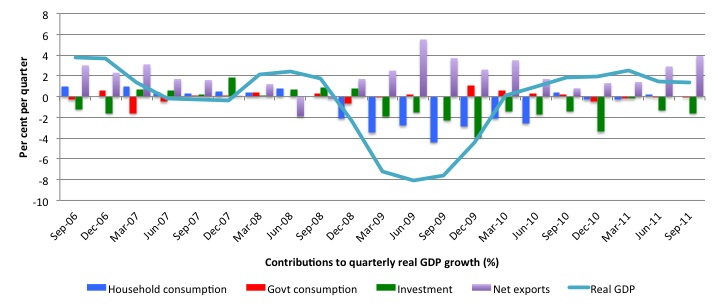

Which component of expenditure were responsible for the sharp contraction in real GDP growth. The following graph shows the quarterly contributions (percentage points) of each of the main expenditure components from September-quarter 2006 to the September-quarter 2011. I should note that the data for government only relates to consumption expenditure and so gross capital formation (investment) includes both public and private investment.

With the investment contribution clearly negative as the crisis worsened and real GDP growth declined very sharply, the lack of government consumption support through this period is notable and made the crisis much worse than it should have been.

One reason for this failure of government to respond to the crisis with a appropriately-sized fiscal stimulus lies in the on-going process to meet the Maastricht criteria. Macroeconomic policy over the last several years has been dominated by the Government’s intention to move to the Euro – a process that has been suspended a few times since 2002 because the aggregate indicators are outside the dimensions permitted under the Stability and Growth Pact strait-jacket.

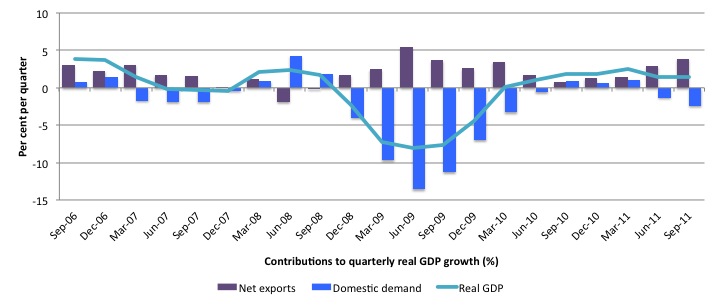

The next graph simplifies the previous graph by showing just the contributions to real GDP growth from domestic and external demand. It is clear that domestic expenditure collapsed while net exports continued to play a positive contribution.

Now what has been going on recently?

The UK Guardian article (January 5, 2012) – Hungary’s woes provide yet another reason to worry about European banks – stated that it was:

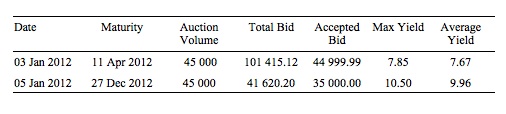

It’s time to get seriously worried about Hungary. Thursday’s debt auction was a disaster. The country was obliged to pay 9.96% for short-term debt and didn’t even raise the 45bn forints it was seeking via auction; it got just 35bn, presumably because it turned away bids pitched at 10% or more.

Yes, the numerical information is fact.

You can access all information regarding the public debt management in Hungary from Government Debt Management Agency Limited (ÁKK), which was formed on March 1, 2001 and is 100 per cent “owned” by the Ministry of Finance. So it is another one of these legal illusions.

It is basically an arm of the government treasury operation but claims to be an “independent corporation”. These arrangements are common around the world but ultimately have no operational significance. Just as their operations etc were created by law – Act on Public Finances (Act XXXVIII of 1992) – (a political choice) they can be changed by law as the politics dictate.

That is, there are no intrinsic financial constraints that govern the operation or existence of these types of agencies.

The following Table (compiled from AKK data) shows what the fuss is about in terms of the recent bond auctions.

The treasury bills auctions over the last few days have “failed” in the sense that the private bond investors have demanded yields (offered lower prices) that are acceptable to the Government). In the first auction (January 3, 2012) there was enough volume (that is, the private markets tendered amounts more than being sought). By the second auction, the bids were below the auction announcement overall

The Guardian article opines that:

The backdrop is well known. The Hungarian currency is in freefall (down 18% against the euro in six months) despite rate hikes designed to shore up confidence and protect mortgage borrowers who have (ridiculously) taken out loans in foreign currencies. The government needs to raise about $16bn this year and Hungary’s banks require foreign lines of credit.

I will come back to the assessment that the private borrowing in foreign currencies is deemed “ridiculous” another day. It is an important part of the story. But here is some information.

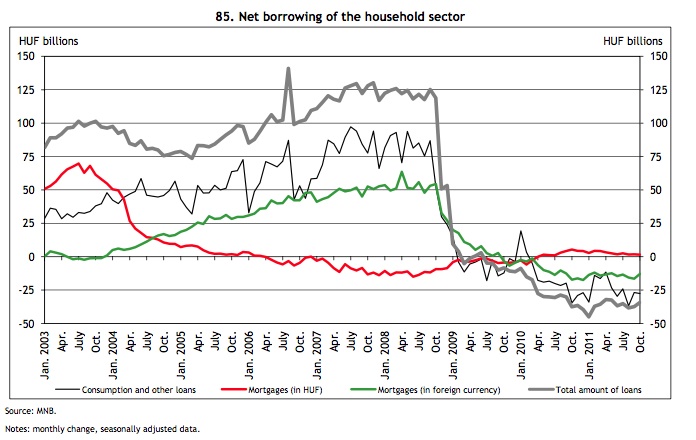

The following graph is taken from the latest Chart Pack from the MNB. You can see that as financial liberalisation caught on in Hungary foreign currency loans have dominated the private housing mortgage market.

The banks, heavily privatised when Hungary moved into its neo-liberal phase (post-Soviet) are now mostly foreign-owned and there were no controls on the source of loans for the domestic housing market.

While the majority of household debt is in the form of housing mortgages a wide range of new debt sources grew with liberalisation. The Financial Accounts of Hungary 2008 – a publication of the MNB says that:

The majority of the increase in the loan portfolio affected foreign exchange loans as the interest rates on these loan structures are significantly lower than those of forint loans. Initially, households used FX- based loans to finance vehicle purchases, and subsequently FX-based loans were granted for real estate purchases and consumption purposes also. In the period 2000-2003, forint loans gained ground in the housing loan market in state subsidised loan structures. In 2004, however, demand for forint housing loans dropped due to the tightening of subsidised housing loan conditions, and to compensate this decline, banks began to offer foreign exchange products with small instalment amounts. Currently, the stock of FX loans represents 60% of the overall loan portfolio; two thirds of consumer loans and nearly one half of real estate loans are FX-based loans, disbursed predominantly in Swiss francs.

This is a pattern we have observed in other former Soviet-satellites (including Latvia and Estonia). I provided some analysis of what happened in Latvia in this blog – When a country is wrecked by neo-liberalism.

Liberalisation saw a proliferation of international banking in these nations and those organisations (or non-bank offshoots) gained a huge presence and began to dominate mortgage origination. The financial engineers pushed credit denominated in foreign-currency at a pace thus leaving the home buyers extremely exposed to foreign exchange fluctuations (in Hungary).

Why did the government not place restrictions on the home mortgage market? Why did it allow around a huge proportion of mortgages to be written in foreign currency? Why did it not regulate the foreign banks that swamped the Hungarian financial sector?

MMT would point to the failure to regulate the financial sector appropriately (particularly the role of banks) which allowed to many households to take on ridiculous levels of foreign currency debt to maintain the real estate boom.

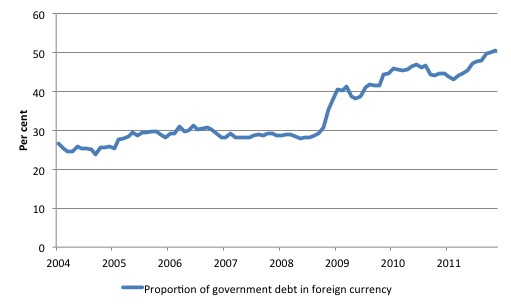

But the major deviation in currency sovereignty, is the large proportion of foreign currency-denominated loans held by the central government. Once a currency-issuing government borrows in a foreign currency they effectively surrender their risk-free status in bond markets and become exposed to default risk on that debt.

Then they are back in the hands, to a certain extent, of the private bond markets.

You can download very detailed government debt data from the – AKK. Data is available in annual frequency from 1990 to 2004 and then monthly from January 2004 to November 2011 (latest).

The following graph shows the proportion of total central government debt denominated in foreign currencies. In 1990, that proportion was 2.4 per cent. The proportion rose quickly once the Soviet system fell but then stabilised until 2008. After that it has accelerated quickly.

The higher is the foreign-currency denominated debt ratio the more reliant the nation becomes on expanding its net exports to pay for it. Please read my blog – Modern monetary theory in an open economy – for more discussion on this point.

If a nation has issued foreign-currency denominated debt its external risk rises. If this debt is issued by private firms (or households), then they must earn foreign currency (or borrow it) to service debt. To meet these needs they can export, attract FDI, and/or engage in short-term borrowing. If none of these is sufficient, default becomes necessary.

There is always a risk of default by private entities, and this is a “market-based” resolution of the problem.

This will become a major issue in Hungary now as the forint depreciates – adding revaluation stress to the outstanding private foreign-currency debt.

In the case of the government foreign currency-denominated debt, there are additional problems. Default becomes more difficult because there is no well delineated international method. Often, the government is forced to go to international lenders to obtain foreign reserves; the result can be a vicious cycle of indebtedness and borrowing. The IMF is already involved in Hungary and wants to impose even more ideological design on the system.

There is also a controversy concerning reports that the government wants to access central bank stocks of foreign exchange reserves. The MNB has significant foreign currency reserves.

In addition to that controversy, part of the current crisis appears to be the reaction by the private bond markets to the legislation passed on December 30, 2011 by the Hungarian parliament which increased the size of the MNB’s interest-rate setting board. Additionally, there is a debate going on to merge the central bank with the prudential regulator and reduce the position of the central bank governor.

All these developments and proposed developments are being criticised by the neo-liberals who claim they compromise the central bank independence. I will provide some specific discussion of these political moves in a later blog.

Please read my blog – Central bank independence – another faux agenda – for more discussion on the general issues here.

The problem is that these developments horrify the IMF and the EU and the bond markets are just following the trail of fear that the Troika elites are mounting.

On top of the problems that arise from having a large exposure to foreign currency denominated debt, the Hungarian government is also caught in two additional “pincer movements” of its own making.

First, its options have become constrained by its obsession with joining the Euro. Like all the previous EMU hopefuls it has started on a long journey to meet the Stability and Growth Pact (Maastricht requirements) and has been systematically constraining its discretionary net spending at the expense of the prosperity of its population..

In a sense, the crisis seems to have been a less important event for the Government than the Euro-process, which helps explain why the real GDP growth collapse has been so severe.

Second, the Government has also imposed its own “fiscal rules” guided by the non-elected “Fiscal Council” which seemingly can override the decisions of the elected government.

The MNB publishes an annual document which provides a very detailed analysis of the developments in the Hungarian and Euro economy from the angle of appraising the suitability of adopting the Euro as the national currency. According to the Analysis of the Convergence Process 2011, we learn that:

Legislated by Parliament and now in force, the so-called real debt rule prohibits the real value of the national debt from being increased from one year to the next. Furthermore, the Constitution requires that the indebtedness ratio of the central budget be decreased each year until it reaches the 50 percent threshold. Of these two provisions, the real debt rule – if the real GDP growth rate is positive – is more restrictive in nature. That said, these rules do not speak to the methods of achieving these targets, leaving these considerations up to the legislature.

The fiscal responsibility Act, adopted in 2008, not only enacted a series of fiscal rules but also set up a legally independent institution, before the entire framework was overhauled in 2010. As a result of this revision, the gdp- proportionate debt ceiling was enshrined in the Constitution, while the country’s Fiscal Council – after having also been restructured – was vested with broader powers to control fiscal processes or, as the case may be, to even block the legislative process. In contrast to the past, however, the reformed Fiscal Council no longer continuously monitors fiscal processes throughout the year, nor does it promptly assess the fiscal impact of individual amendments, since its scope of inquire is largely confined to the period covered by the prevailing Budget Bill for the upcoming year.

So the Government is deliberately constraining its fiscal capacity to service the demands of foreign elites (and its own elites) which will make the current crisis worse.

The problem is that both the private and public sector in Hungary are now very exposed to the assessment of the bond markets and exchange rate movements which follow.

In the latest edition – Analysis of the Convergence Process 2011 – the MNB say:

… higher- than-average balance sheet adjustment may be necessary due to the fact that debt is denominated in foreign currency, where changes in the exchange rate are obviously very unpredictable … Overall, the balance sheet adjustment in the private and particularly in the household sector – on a larger scale than in the core euro area countries – will constitute an asymmetric shock in the coming years, possibly further strengthened by the banking sector’s dependence on external funds and its declining capital accumulation capability.

And the problem also extends to the public sector because it has such a large exposure now to foreign currency-denominated debt.

The Analysis of Convergence Process 2011 Report referred to above says:

As a result of the high foreign currency ratio of the public debt and the relatively short average maturities, rising yields and a weakening exchange rate of the forint may trigger a substantial increase in the indebtedness ratio. At higher debt levels, the rate of indebtedness becomes more sensitive to declines in economic output and fluctuations in yields.

Put together – a very difficult situation is ahead.

Conclusion

Life in Hungary will get very difficult because it is now so exposed to movements in its currency. The private sector will experience significant reductions in its real standards of living as they struggle to service foreign-currency denominated debt with a declining domestic income.

The government will also be pushed towards default by a slowing economy, the massive revaluations of its foreign-currency denominated debt as the currency falls and the declining capacity of the economy to generate export growth (as the rest of Europe slows).

It is a very dire situation and the bond markets are reacting to the increased risk of default.

The lesson is that Hungary does not provide a case against the insights provided by MMT. Budget deficits in a sovereign, floating, currency never entail solvency risk. Sovereign government can always “afford” whatever is for sale in terms of its own currency. It is never subject to “market discipline”. A sovereign government spends by crediting bank accounts, and it can never “run out” of such credits.

I repeat that when analysing a specific nation there are so many aspects to draw together. I have just skimmed the surface and deliberately left a lot of interesting and relevant issues out – to allow a focus on the specific MMT issue – the loss of currency sovereignty.

The blog was just a sharing of some research effort about Hungary (which really all my blogs are meant to be). There is a lot more analysis needed of this country and its desire to join the Euro to really get to the bottom of their current dilemma.

Saturday Quiz

The first Saturday Quiz for 2012 will be available some time tomorrow. I hope it is a bit of fun.

That is enough for today!

Good day,

just a very short question. A country never faces solvency risk when borrowing in its own currency provided that it satisfies all the necessary conditions, okey. Even though Hungary has foreign denominated debt, the yields are rising on forint-denominated debt. How comes?

I mean, is it that market is afraid of Hungary’s government defaulting on foreign debt which would lead to a political choice to default on forint debt as well? Or is it impossible to default on foreign debt but still service domestic one? Or is the market afraid of possible inflation because of deprecation?

So the main question I have – why yields are rising on forint-denominated debt, not only on the foreign debt?

As per excellent analysis from Moody’s, Fitch and S&P, Hungary’s problem is one of its external debt built up as a result of huge current account imbalances over the years.

As per end of 2010 data, Hungary is the 2nd top debtor with its Net International Investment Position as a percentage of GDP at minus 116.9%, even worse than Portugal’s minus 116.6% and second only to Iceland (minus 673.1%). (Data via Philp Lane’s presentation). The NIIP is expected to have been minus 131% of GDP at the end of 2011 according to Moody’s.

As long as the central bank regulates banks such as setting limits on its net open position in foreign currency, the official sector (central bank, treasury or exchange stabilization fund) has no choice but to act as a borrower of the last resort in foreign currency. If limits are not set, then the banking system itself is taking a huge amount of risk. As per literature on foreign exchange market microstructure, banks’ fx dealer desks are always trying to offload its net open position in the market and if it is not successful, official intervention is the only way out.

Most nations find it difficulties in getting their currencies accepted in international markets. Either nations are net creditors and well off or if they are net debtors and they face difficulty. The United States, UK, Australia and to some extent Canada are the only net debtor nations who have been relatively successful. Even the UK has faced a lot of issues in international currency markets over so many years.

The case of Hungary proves exactly the opposite of what is claimed in this blog post. The case of a pure float is a myth – its just a luxury of a few nations who have managed to make their currencies acceptable in international markets.

Ramanan, although it may be hard for many countries to run long term trade deficits with a free floating currency (not that it would work with a pegged currency either); isn’t it perfectly feasible for them to continue with balanced trade if they have free floating currencies? Don’t free floating currencies help steer the economy towards having trade balance with the rest of the World?

The story goes the same about all those Eastern European countries after they became “Western”. First their commercial banks have mainly domestic owners. The banks are undercapitilized and underregulated. Elected governments don’t even know how to regulate banking sector properly. There are a lot of bankruptcies, some people go to jail. Then foreign capital arrives and the bank owners are made generous offers for their market share in the sector. Now everything tends to stabilize. The new kids of the neo-liberal mindset are even more neo-liberal than their Western idelogical allies. These countries have pegged currencies usually. Foreign banks are offering loans in domestic currency at a higher rate. That doesn’t mean that those loans are really taken out in a foreign currency. The loans are really in domestic currency. When the crisis hits, the government could let the currency float but that would mean higher debt burden for most of the debtors. Hungary let Its currency float and is now dealing with the aftermath, Estonia and Latvia didn’t.

Is Turkey doing better than Eastern Europe? Are they more of an emerging economy rather than a submerging one?

Given the data on this threat, it seems to me the Hungarian population learned from experience that consumption expenditure financed through borrowing satisfies preferences for consumption now rather than later, but not for a long time. GDP, nominal or real, measures only the value of market transactions. It is not surprising that the aggregate value of market transactions declines when repayment of loan time arrives.

The data also suggests that, in aggregate, Hungarians were quick to substitute mortgage loans, issued in local currency units, for loans issued in foreign currency units as the value of the local currency unit declined in relative to say the Swiss fr.

Whether or not GDP is a relevant measure of standard of living is moot in general. In the case of a country like Hungary, it is conceivable there was pent up demand for consumption goods which have features of ‘capital goods’ (eg white goods, cars, furniture..). To the extent that this consideration is applicable to individuals, their standard of living may be approximately unchanged as the period of borrowing was succeeded by repayment. Some individuals may have become relatively very wealthy during the financial boom period but others may have lost their proverbial shirt or became unemployed or were never paid enough to qualify even for a Swiss loan at ‘low’ interest rates ex FX risk. The point I am trying to make is that many interpretations (hypotheses, assumptions) can be read into aggregate data and all can be wrong.

But according to MMT what are the consequences of fiscal deficits on the behaviour of the currency in the forex exchange market? I tried to find out some posts about this issue but i can’t find anything.

@Ramanan

The case of Hungary proves exactly the opposite of what is claimed in this blog post. The case of a pure float is a myth – its just a luxury of a few nations who have managed to make their currencies acceptable in international markets.

Why do you say that? From what I understand, the point of the post is that MMT is not contradictory to the Hungary case, because even though they use their own currency, they surrendered their sovereignty.

Surely, even if the forint goes down the drain, should Hungary be free of debt in foreign currency, the only consequence is that imports become too expensive. Hungary would still be free as to what fiscal policy they want to implement, and wouldn’t be forced to bow to any foreign influence in exchange of foreign currency to meet their due repayments.

This would ultimately lead to less imports, and probably more exports as Hungarians goods and services become cheaper for the rest of the world. Should Hungarians really miss the shiny things they used to import, and provided they have manufacturing capacity and abilities for it, they could even start producing them themselves. If there’s demand for some goods and services backed by enough forint surely some entrepeneur will come forward and fulfill this demand.

Admittedly there are things that a country necessarily imports (I’m thinking natural resources not available in the country, like maybe oil and gas), but unless Hungarians sit on their thumbs all year long, they’re bound to find some goods and services that they could trade against some of these necessarily imported things, aren’t they?

My question is: can a country like Hungary entirely avoid foreign currency debt?

Hungary is a net exporter but may want to borrow dollars/Euro to trade in some markets, what then. Maybe only large exporters, like Japan and Germany, or importers with world reserve currency (USA) can afford to entirely avoid foreign currency debt?

Hungary’s central banks has increased the interest rate twice within a month’s time, from 6% to 7%, mainly in an effort to defend the exchange rate. Personally, i cannot find forwards on the interbank rate for 2012, but it seems quite reasonable that the interest rates requested on government debt is just a forward-looking projection of the interbank rate for the securities lifetime, something completely consistent with the MMT principles. What is worrying (and should be answered) is the fact that bids did not even cover the offered amount in the second auction. It would be very interesting to find out the institutional arrangements of the auction system in Hungary (minimum primary dealers required bids, central bank participation, etc).

“My question is: can a country like Hungary entirely avoid foreign currency debt?”

It’s sovereign can avoid foreign debt and should do like the plauge. Private sector foreign currency debt is the problem of the creditor and will be resolved via the bankruptcy process.

“If limits are not set, then the banking system itself is taking a huge amount of risk. As per literature on foreign exchange market microstructure, banks’ fx dealer desks are always trying to offload its net open position in the market and if it is not successful, official intervention is the only way out.”

Why.

Why not let the banks go bust, and the creditors in the foreign currencies take the hit.

There is a standard mechanism for bankruptcy for private entities that resolves these problems under the law.

Banks should be built so they can go bust, and the central bank must never bail out a bank in a foreign currency if it means taking on the risk itself.

Free floating they say. If it is free floating, why is there need to defend FX rate by hiking up interest rate?

“Expectations Hungary’s central bank will resort to steep rate hikes to defend the plunging currency have caused the interest rate swaps curve (IRS) to invert, with the 2-year part of the curve trading 60 basis points above the 10-year.”

http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/01/05/hungary-rates-expectations-idUSL6E8C532V20120105

I remember when GFC started there was huge uproar in Hungary that they must not let FX rate to depreciate because so many housing mortgages were denominated in foreign currencies.

Exchange rate movements kinda prove this point:

http://www.google.com/finance?q=EURhuf#

When GFC started there were brief ~25% depreciation vis-a-vis euro, then they hauled it back to ~7% depreciation, until they lost control again last summer.

This does not sound like free floating currency to me. Maybe “snake in a tube” kinda arrangement.

JKL:

To attempt to answer your question about why domestic currency interest rates are rising. I believe it is to compensate for the drop in the value of the forint in the foreign exchange markets. And this is due to the fact that about 50% of the government debt is in foreign currency, which must be obtained through trade. If no government debt, or very little, was in foreign currency, then the Hungarian government could control its domestic currency interest rate. I would appreciate comments or corrections. Regards.

Excellent post on the Hungarian situation, which certainly does not violate MMT. But why did Hungary borrow in foreign currency in the first place? Were they enticed by the mirage of lower yields?

Ernestine,

Let me comment on the following statements you made:

“To the extent that this consideration is applicable to individuals, their standard of living may be approximately unchanged as the period of borrowing was succeeded by repayment.”

…

“The point I am trying to make is that many interpretations (hypotheses, assumptions) can be read into aggregate data and all can be wrong.”

We are not talking about an abstract colony of space ants living on one of the moons of Jupiter where all we know about them is 64kB of data. We are talking about real people living in a country you can visit. Mind games about interpreting the data “according to this or that model” are in my opinion entirely inappropriate. Sometimes anecdotal evidence may shed more light than just aggregate numbers, that the GDP dropped a few %. One of my mom’s friends visited her Hungarian friends a few months ago and what she saw stunned her. The only good thing is that she lost 4kg over a few weeks time on these “holidays” what is not bad for a lady in her 70ies. It is not that she couldn’t afford to buy tasty Hungarian food but in order not to upset her hosts she ate the same food they had (we are talking about retired academic teachers, people quite sensitive to old-fashioned Continental European manners). There is simply a lot of impoverished people in Hungary, it is way worse than in Poland which so far avoided the hard landing.

The mechanism of screwing up people on foreign denominated loans repeated itself in many countries of the region including Poland. I told my Polish friends about that in early 2008, they laughed at me paying 9% on my mortgage. They started crying in 2009 when the principals of their mortgages in CHF went up by 50% (it is even worse now). I can post a copy of these emails illustrating their “bounded rationality” at work. My friends are either engineers or managers, not some random uneducated people. You stated that “the Hungarian population learned from experience that consumption expenditure financed through borrowing satisfies preferences for consumption now rather than later, but not for a long time”. The issue was a systemic breakdown manifesting itself in a change of exchange rate trend not some random mistakes and mis-allocations made at the individual level. Some may relate it to “fallacy of composition” however it is not exactly that fallacy. The inflow of foreign currency caused by the speculative capital tilted the exchange rate one way. The outflow caused by the foreign capital flight moved it the opposite way. The individuals were trapped between the cogs of macroeconomic history – as usual. Only the government could have prevented that process by introducing an appropriate regulation but it didn’t.

The same applies to taking foreign loans denominated in Euro by the governments bent on joining the Eurozone. These countries are democracies and in the mid-2000s the ruling parties had to bribe the electorate with short-term increase in consumption of often luxury goods and an illusion of wealth coming from the housing bubble. This is the real political business cycle. A lot of the luxury stuff (financed by loans) came from Germany, the economic power house of the region and the Germans were happy what itself was also good – but the process was not sustainable.

NB there is a very interesting study about housing bubble in Poland available in English on the Internet.

“Jacek Łaszek, Marta Widłak, Hanna Augustyniak House Price Bubbles on the Major Polish Housing Markets”

Once there are signs of a currency flight, not much can be done to stop this process. According to the leading pro-European Polish newspaper this process has already started in Hungary – this should explain the elevated bond yields. I am not a fan of hyper-nationalistic Viktor Orban (some people accuse him of fascism). I am simply sorry for the people living in that beautiful Central European country. The vicious cycle of high inflation caused by the currency flight and falling exchange rate, bankruptcies, austerity and foreign meddling is impossible to stop using conventional policies until it runs its course. The governments may be so desperate that it may purchase EUR on the market thus causing the exchange rate to fall even further. Not only speculators are to be blamed for the dire outcome it is simply the natural behaviour of the system.

Money is not neutral, is it?

Adam (ak),

You selectively quoted from my post. You apparently deliberately ignored my indication of changes in income distribution and the role of financial markets in these changes. So, it is I who is talking about individulas and not numerical aggregates.

As for casual observations, just the other day I met a family from Poland who fell for the Swizz ‘low interest’ rate loans.

As for Hungary, I’ve been there but at a time when the Iron Curtain was still in place. On these visits I learned, at an early age, that both sides of the Curtain talked propaganda. I’d never seen such huge differences in the condition of living between an academic and a porter in ‘the West’ as I saw in Budapest (image destruction about the East) and the political talk among people in Budapest was more vocal than in ‘the West’ (image destruction about the West). Moreover, small scale private enterprise did exist in Budapest (car mechanic working from his garage), queing for food in Budapest was no more time consuming than queing at the check-out counter at any arbitrary supermarket in ‘the West’. Budapest overall was a lively and well illuminated metropolis with great charm but in the countryside there were villages without electricity.

Otherwise, enjoy your conversation with yourself.

Neo-liberal asset-grap program:

First, they tell these nations to liberalize capital accounts, i.e. allow foreign currency loans.

When loans start to come they push currency upwards and capital account in to surplus, and by accounting identity, current account in to deficit.

Process could go on for a decade or two. Private sector becomes ever more indebted in foreign currencies. Central bank is told to defend FX rate, which has become now crucial, by raising interest rates. This works by discouraging domestic borrowing ‘cos interest rates are so high and subsequently encouraging foreign borrowing, i.e. attracting capital inflows on current account. All this time currency is “overvalued”, supported by these FX inflows.

Private sector becames ever more indebted in foreign currencies (and, indeed, often public sector too). Naturally there is a limit how much private sector can become indebted, let alone in foreign currencies. When those foreign inflows stop, currency plummets. This pushes up value of all FX loans in domestic terms. Currency plummets even more when flows reverse when they try to repay these loans.

Now stage is set for mass bankrupty & asset grap: when liabilities swell in value, while assets remain same, many households and companies find themselves bankrupt. Asset liquidations began, offering wealthy foreigners plenty of opportunities to grap valuable assets at firesale prices. Foreign creditors are bailed out by IMF and EU.

Does MMT favor foreign exchange controls and/or capital controls? Most of the MMT documents I’m reading focus on explaining a fairly self-contained system, and emphasize the freedom of action of the sovereign currency issuer within that system, but I’ve found little information on exchange rates and issues such as capital flight. For example in Hungary, even if the government hadn’t issued foreign-currency-denominated debt (and even in the present situation the government isn’t too threatened in the short-term as they have considerable reserves), there would still be the issue of all the private debt in foreign currencies.

Hepionkeppi,

The process of bankruptcies and wealth redistribution does not necessarily involve “wealthy foreigners” (eg USA housing).

feel free to read ‘exchange rate policy and full employment’

that I delivered at Bill’s conference way back at:

http://moslereconomics.com/2010/10/04/exchange-rate-policy-and-full-employment/

Warren Mosler

Ernestine,

If you haven’t clearly stated what your point is, please don’t be surprised that someone may have misread your comments. So do you agree with the Bill’s analysis of the Hungarian crisis or not? If you do not agree with his analysis please give clear arguments where he is wrong. If you think that he missed something important, please explain that in such a way that any reasonably intelligent person can understand the issue better when he/she reads your comments.

The point that data can be interpreted in many ways or that “the process of bankruptcies and wealth redistribution does not necessarily involve wealthy foreigners” doesn’t add much to the debate I am afraid. So is Michael Hudson right or wrong when he writes that there is a plan created by Western European capitalists to take over the real assets in Eastern and Central Europe and put the majority of the people living there under debt peonage? We can always say that there are other, more politically palatable explanations possible, we can endlessly dither and keep saying “But you are better as a debt peon now than as a state serf under scientific communism, aren’t you? And since you acquired these 10 shares in XYZ when you were enrolled in the compulsory pension plan you are a petit bourgeois too”.

I may be a typical half-glass-empty person and I say “but this is not what was promised to us so go to hell with all these inventions to which “There Is No Alternative”. They cheated us, this is not what we deserve, this is now what I fought for, I apologise for being on the neoliberal side in 1988/1989, let’s try again.

I dare to say there is special “science” invented to deal with examining these “other explanations” in terms of the “objective” laws of development of societies centred around the so-called “market”, similar to laws of physics. And “there is no alternative”. This is mainstream economics – as defined by Paul Davidson in “John Maynard Keynes (Great Thinkers in Economics) “. I personally bin “mainstream economics” together with astrology, homoeopathy, scientific Soviet communism and medieval Christian or Muslim theology into the category of pseudo-science developed as a tool to commit intellectual fraud. This is not necessary a 100% result of conscious conspiracy since these systems of toxic memes often live independently of their creators and may be equally toxic to the people who spread them as well.

If what Bill wrote is not enough, there are other economic writers who reached similar conclusions as well. I am too lazy to quote Steve Keen here but even if I disagree with some of his models I think that he did a reasonably good job in uncovering the mechanism of this fraud.

I generally assume that if somebody hasn’t understood me – even if that person totally disagrees with me – it is my fault as a communicator. I can understand a “small target” debating strategy but responding to statements like “enjoy your conversation with yourself” is rather pointless “in the long run” and I can do it only once. If I have misunderstood your comment again, please accept my sincere apologies. But I am not so sure about your intentions.

Could you tell us what your intentions are on this forum?

Is your intention to contribute and enrich the stream of ideas called “MMT”? That’s great. Or do you want to mount a fundamental merit-based critique of these ideas? If this is the case I am even more happy to read your comments because a merit-based critique made by the person of your intellectual calibre will be an essential part of a healthy debate. There are some statements made by some MMT theorists I may have reservations about. But if your intention is to snipe at Bill or some commentators and keep saying “this is irrelevant and not new, others have said the same” or “other explanations are possible” (this is how I read some of your comments) then I am afraid this activity is waste of time for both the writer and the readers of the comments.

Disclaimer: I may be totally wrong in assessing the situation but if this is the case please show me where I made a mistake and I am happy to admit it publicly on this forum.

stone says:

Friday, January 6, 2012 at 22:21

“Is Turkey doing better than Eastern Europe? Are they more of an emerging economy rather than a submerging one?”

You may have seen this?

http://www.atimes.com/atimes/Middle_East/MH10Ak01.html

Thanks for the link to ‘Tally sticks’. Fascinating.

My question is: can a country like Hungary entirely avoid foreign currency debt?

Hungary is a net exporter but may want to borrow dollars/Euro to trade in some markets, what then. Maybe only large exporters, like Japan and Germany, or importers with world reserve currency (USA) can afford to entirely avoid foreign currency debt?

Even importers manage to avoid foreign currency debt. Before Portugal joined the euro, people took out loans in Escudos and repaid them in escudos. The Government also issued debt in Escudos, yet our trade balance has been in deficit since 1974.

Adam (ak)

You failed to acknowledge that you quoted me out of context. The context is the income distribution and possible changes in this distribution in relation to the financial markets bubble (disaster really).

I feel obliged to answer one of your questions, namely what is my intention on this blog-site. I’ve answered this question on another threat but I consider it fair enough to say it again. I try to find out what “MMT” is.

Subject to rvising my opinion, possibly as a result of discovering the formal model one day, my opinion todate is that I do not agree with “MMT”. As a sign of good will, I’ll provide a view arguments in support of my humble opinion.

1. Hungary. I believe I have illustrated already that the data contained in the diagrams allow for more than one interpretation. Therefore nothing can be concluded regarding ‘MMT’.

2. Even in the restrictive framework of macro-economics, the distribution of income is an important variable. ‘MMT’ is silent on this.

3. IMHO, the JG does not ‘anchor’ anything in a monetary economy other than providing an institutional framework for a permanent underclass while allowing politicians to publish the ‘message’ that we have ‘full employment’. I do not wish to suggest this is Bill Mitchell’s intention. On the contrary, I believe he is sincerely concerned with the hardship caused for many unemployed. Other relevant points have been made by some commenters regarding the tax treatment of charities. MMT totally ignores the debt generating capacity of the private financial sector down to trade credits among small business. But this is the actual problem. MMT has no solution for this problem.

4. MMT ignores insights on what might ‘anchor’ a fiat system monetary system, namely

a) very strong assumptions on risk aversion on part of each economic agent (you and me included). On the contrary, Bill Mitchell criticises the countries where many, but not all, economic agents are risk averse (ie set themselves limits on issuing debt securities). Whether this is due to historical reasons (Germany) or the education system or some combination thereof or other reason, including regulation, is irrelevant at present. Is it really that surprising that governments, seeking to represent the wishes of their people to have a stable economic environment but lack a binding constraint (prisoners dilemma type problem) want to become EURO members, knowing very well the rules of the game (technical meaning of ‘game’)? I don’t believe it is surprising.

b) Quantity constraints on the issuing of various types of financial securities, including zero quantities for some types of derivatives securities, and including ‘money’ (a type of security in more contemporary frameworks).

(There seems to have been a default ‘anchor’ between the 1970s and 2008, namely ignorance on part of the populations in just about all countries. ‘Communicators’ talked about ‘confidence’.)

It is not my responsibility to make you understand and it is not your obligation to bother with what I write.

If Bill Mitchell is unhappy with my comments, I am happy to act on the first hint thereof and disappear quietly.

Ernestine,

To answer some of your comments:

1)Question:

“…the data contained in the diagrams allow for more than one interpretation.”

Answer:

Bill himself said the following above:

“This blog is not intended to be a definitive statement about Hungary. It reflects some of the products of an on-going research effort. But it should highlight some of the key MMT issues that the mainstream media is ignoring.”

3) Question:

“IMHO, the JG does not ‘anchor’ anything in a monetary economy other than providing an institutional framework for a permanent underclass while allowing politicians to publish the ‘message’ that we have ‘full employment’.”

Answer:

I’m sure Bill recognises this argument, but he also referes to the JG paying a minimum LIVING wage. In addition I would add that JG DOES anchor inflation, by providing a buffer stock of people employed at a minimum living wage, rather than providing a buffer stock of UNemployed people living (if you can call it living) on poverty levels of benefits. It’s an improvement, however way you look at it. Bill also only says that JG provides the minimum necesary to provide full employment with price stability – in other words a Job Guarantee is the least a government could do.

4 a) Question:

“Bill Mitchell criticises the countries where many, but not all, economic agents are risk averse (ie set themselves limits on issuing debt securities).”

Answer:

Bill says that truly sovereign governments do not need to issue debt $-for-$ to match their deficits, and he is generally averse to government debt issuance when it is not necessary. This is actually key to MMT. Yet, even if sovereign governments choose to issue debt to match their deficit (aleft-over from the gold standard era), it is still better under MMT to run a sufficiently large deficit to provide full employment.

Kind Regards

Charlie

CharlesJ, I didn’t ask you any questions. FYI, your comments make no sense in relation to what I wrote in reply to Adam (ak). .

Ernestine, my first realisation of MMT was on the nature of money and on the unity of national accounting.

If you’re not on the eurozone take out a banknote and ask: where did this come from? From the Government, either via the Mint or the Central Bank. Thus how can taxation happen before spending if that which you will use to pay taxes came from the Government?

The second realisation is that someone’s deficit is someone else’s superavit. It’s very simple. Imagine I have two pencils. I give you one pencil. I have a deficit of one pencil and you have a corresponding superavit.

Everything else flows from there. Confronted with the first realisation, you will probably wonder what keeps the Government from spending all it wants. Inflation will come to mind, but if you check ECB or FED data, you’ll see that money supply and inflation are not correlated – there must be something else to inflation then. And you’ll come into contact with other theories, and end up associating inflation with productive availability. The second realisation will lead you to ask: who pays/wins with Government superavits/deficits.

seeking to represent the wishes of their people to have a stable economic environment but lack a binding constraint (prisoners dilemma type problem) want to become EURO members, knowing very well the rules of the game (technical meaning of ‘game’)? I don’t believe it is surprising.

Well, their peoples’ wishes were indeed stability and growth, and in that measure the Euro is a failed promised. I, however, am glad to say the Portuguese always opposed the introduction of the euro. And apparently the Germans did too. We were both right.

Ernestine, if I may chime in…

1. I agree. The title of this blog is over-exaggerated. Hungary does NOT show anything serious about MMT simply because Hungary has not done anything MMT specific. But at the same time Hungary is a clear failure of the “mainstream”. Surely, being anti-mainstream alone does not prove anything about MMT.

2. + 3. “the distribution of income is an important variable” and “sincerely concerned with the hardship caused for many unemployed”. You have a clear contradiction in two sentences though I do somewhat agree that the distribution of and volume of financial wealth deserves much more space than it has. I have a personal distaste for budget deficits which at the very least indicate economic inefficiencies of the institutional system of the economy. Besides that accumulated financial wealth, aka private sector savings, represent a hidden and latent demand which can be triggered into inflation much faster and beyond what even a fully MMT-compliant economy can tolerate. Japan is intrinsically in a very unstable situation and MMTers’ over-use of it as a role model can easily back-fire. However overall I do not agree that MMT is silent on the topic of income distribution. To be bothered with income distribution you have to have income and this is what MMT starts with which is a huge progress vis-a-vis current regime.

4. That is just your opinion. I believe that MMT provides a critical insight into pricing dynamics of fiat money and that is that without government ratification in terms of spending any private sector invented price of money is meaningless and unstable. And ratification can feed through different spending channels. Only government spending defines the long-term price level of fiat money. Be it gold, bananas, fx rate or wages.

Dear Sergei (at 2012/01/10 at 8:48) and Ernestine

Sergei said:

The point of the blog was to respond to many enquiries that I had received alleging that Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) could not be a general explanation for the way monetary systems operate because while Hungary issued its own currency and floated it on international markets the bond markets were still imposing higher interest rates and limiting the capacity of the government to run deficits.

The blog clearly showed that Hungary violated a basic condition for true sovereignty – the government was heavily indebted via foreign-denominated loans and so the developments did not violate basic MMT insights.

That motivation was clearly outlined in the introduction. The developments in Hungary clearly demonstrate that when a nation borrows in foreign currencies it loses its sovereignty – a basic MMT principle.

best wishes

bill

Dear Bill,

thank you for your reply. I still beg to differ. The reason is that prices (relative and absolute) are not only influenced by government spending and its financing (eg tax, debt or issuing currency) but also by private debt. Unless one is in a Bretton-Wood type institutional environment where capital controls and fixed but movable exchange rates are allowed, a government does not have control over private debt. Spain and Ireland are good are good examples at present and so are the UK and the USA. Spain and Ireland are EURO members, the UK and the USA are not. The fact is that since the late 1970s the institutional environment has changed under various (promotional) headings and is now widely described as neo-liberalism (EU continental economists described it as ‘naive market economics’). These institutional changes have reduced Keynesian-type aggregate demand management methods to be even more short term than in their original conception.

You have taken on a difficult task with this blog. Please let me know if my comments are a hindrance to your task and I’ll disappear without being offended.

Ernestine – governments have sufficient control over private debt by their control over banking systems, which is not really part of “the private sector”. That government control is not complete and absolute is just an observation that we do not live in totalitarian societies, although we are definitely moving that way, toward a dictatorship of banksters and other parasites & predators, preaching liberty & free markets as they rake in the public money which they glory in denying to people who actually work for a living. If the financiers make a bubble, it will deflate on its own if not supported by the government, which is why the TBTF financial institutions are such welfare queens. And the government always has control over its own spending, enough to always maintain full employment without inflation.

Abba Lerner insisted on floating exchange rates, deriding the “cult of rigid exchange rates”, because there is no good reason for and much harm possible when governments tie the value of their currency to another. And Keynes eventually agreed with Lerner’s “functional finance”, basically an older name for “MMT”, agreed that Lerner was right. (Lerner, for his part, generously attributed the main ideas of functional finance to Keynes.) The post 1971 floating rate regime, the removal of a pointless arbitrary obstacle to prosperity, makes “Keynesian-type aggregate demand management” easier, not harder, as Lerner argued since the 1930s. So this weird modern idea to the contrary, held by many “Keynesians”, is the opposite of what real Keynesians thought.

I very much hope you do not disappear.

Bill, I somewhat disagree with your statement or it requires further clarifications. The National Bank of Hungary has accumulated fx-reserves to the tune of 40bn+ EUR. That is a very significant amount for *Hungary*. This shows that there is a significant *domestic* fx-risk exposure but it tells nothing about *national* currency sovereignty. So while the accumulation of reserves was driven by the central bank policies (neo-liberal euro-convergence and de-regulation of the financial sector) the argument that *Hungary* has lost its currency sovereignty is not all that obvious and/or strong. In fact it is 40bn EUR smaller than the headline figure and the large part of the crisis in Hungary is driven by the resistance of the National Bank to play on both sides of the fx-fence. Given the recent events in Hungary, esp. regarding central bank independence, one can rather see it as a war against bankers. And while the motivation of this war is likely to be wrong (i.e. populism), in the end Hungary might have much higher chances to stumble upon certain MMT ideas, like combining CB and Treasury, than any other country in the world.

Ramanan

You said;

“The case of Hungary proves exactly the opposite of what is claimed in this blog post. The case of a pure float is a myth – its just a luxury of a few nations who have managed to make their currencies acceptable in international markets.”

I think that true sovereignty has not only to do with having your own currency, but also being able to live completely off your own resources. The reason the aforementioned countries can be considered truly sovereign (outside of Britain) is that they do have the capactiy to keep everything within their borders. Britain does have a good enough relationship with us and Australia that they are effectively fully sovereign. Small countries which might not have everything their population desires can have their own currencies (and maybe should) but they still will not be AS sovereign as say the US, Russia, China or Australia. While they can pay in their own currency whatever price is demanded that demanded price may get very high for some smaller economies at times.

Small countries which might not have everything their population desires can have their own currencies (and maybe should) but they still will not be AS sovereign as say the US, Russia, China or Australia. While they can pay in their own currency whatever price is demanded that demanded price may get very high for some smaller economies at times.

It has to be a much smaller country to be that dependent. Hungary has 10m people and a favourable balance of trade, so there should be no problems for Hungarians to have everything they need.

The main resources needed, for me, are labour and land. Maybe Luxembourg couldn’t get live on itself, but most countries, some of then even considered small, can.

@ Geoff : “But why did Hungary borrow in foreign currency in the first place?”

Because the previous government was mad. The Swiss bank authorities even wrote to the Hungarian government asking: “Hey guys, are you sure you know what you’re doing ?”. Easy money.

Nice article!

I’d really like to read your opinion about the 2012-2015 period in Hungary and the recent news in the mortgage topic: http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/01/23/hungary-orbanomics-idUSL6N0V036D20150123