I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Evidence – the antidote to dogma

Evidence is a lovely thing sometimes. Like the speck of blood on a bomber jacket that has finally convicted the racist killers in London, 19 years after the crime was committed. In a different way, economic data is continually flowing in that makes vocal elements in my profession look like idiots. The only question is how long will it take for the rest of the world to know that and for governments to stop being influenced by the opinions of these economists. Over the last few decades I have been compiling interviews and commentaries from leading economists so that I can compare their predictions with the evolving reality. Economists typically make categorical statements such as – rising budget deficits will push up interest rates and choke off private spending – and then buttress those comments with arcane models that were negated both conceptually and empirically years ago. Invariably, when the mainstream economists do make predictions or empirical statements they are invariably wrong and then it is interesting to see how they respond to the anomaly – the dance that follows to try to maintain the upper-hand in the debate. They typically respond by nuancing the issue. But there are also times when their predictions are unambiguously wrong and ad hoc responses (of the Lakatosian type) make them look even more stupid. Then they bury their head in the sand and go into denial mode and their ideology takes over. The best antidote to this sort of dogma is evidence.

Today, I am introducing a new award – the Ostrich Award – for those economists who continually Bury their head in the sand. Here is the trophy:

I should add that I don’t mean to link the beauty of the ostrich with the idiocy of my profession.

Take for example, this very strange – Interview with Eugene Fama – that the New Yorker’s John Cassidy published on January 13, 2010. I have been thinking about this interview for the last two years since I first read it.

Eugene Fama is an economist at the University of Chicago and is most known for his work promoting the so-called efficient markets hypothesis.

This is a hypothesis that asserts that financial markets are driven by individuals who on average are correct and so the market allocates resources in the most efficient pattern possible. There are various versions of the EMH (weak to strong) but all suggest that excess returns are impossible because information is efficiently imparted to all “investors”. Investors are assumed to be fully informed so that they can make the best possible decisions.

I recall one person told me that “you cannot profit by riding the yield curve”. I pointed out that hedge funds profit in this way every day, to which he said that was “impossible”.

But I don’t intend talking about this nonsense.

Fama told John Cassidy that the financial crisis was not caused by a break down in financial markets and denied that asset price bubbles exist. He also claimed that the proliferation of sub-prime housing loans in the US “was government policy” – referring to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac who he claims “were instructed to buy lower grade mortgages”.

When it was pointed out that these agencies were a small part of the market as a whole and that the “the subprime mortgage bond business overwhelmingly a private sector phenomenon”, Fama claimed that the collapse in housing prices was nothing to do with the escalation in sub-prime mortgages but rather:

What happened is we went through a big recession, people couldn’t make their mortgage payments, and, of course, the ones with the riskiest mortgages were the most likely not to be able to do it. As a consequence, we had a so-called credit crisis. It wasn’t really a credit crisis. It was an economic crisis.

John Cassidy checked if he had heard it right asking “surely the start of the credit crisis predated the recession?” to which Fama replied:

I don’t think so. How could it? People don’t walk away from their homes unless they can’t make the payments. That’s an indication that we are in a recession.

Once again he was prompted to think about that – “So you are saying the recession predated August 2007”, to which Fama replied:

Yeah. It had to, to be showing up among people who had mortgages.

He was then asked “what caused the recession if it wasn’t the financial crisis”?

(Laughs) That’s where economics has always broken down. We don’t know what causes recessions. Now, I’m not a macroeconomist so I don’t feel bad about that. (Laughs again.) …

Fama asserted that “the financial markets were a casualty of the recession, not a cause of it”.

Later, in defending the efficiency of financial markets, Fama wondered how many economists:

… would argue that the world wasn’t made a much better place by the financial development that occurred from 1980 onwards. The expansion of worldwide wealth-in developed countries, in emerging countries-all of that was facilitated, in my view, to a large extent, by the development of international markets and the way they allow saving to flow to investments, in its most productive uses. Even if you blame this episode on financial innovation, or whatever you want to blame, would that wipe out the previous thirty years of development?

I was reminded of this interview when I saw the UK Guardian report (January 3, 2012) – Ireland’s house prices at lowest levels since 2000 – which reported that:

Property prices in Ireland are in freefall, according to housing analysts, whose latest figures show that prices in Dublin have collapsed by 65% in five years and by 60% across the country.

A house price index released by the largest residential sales group – the Sherry FitzGerald Group – found that the pace of deflation has sped up in Dublin, while prices across the country are now at levels last seen 11 years ago.

The report says that the “new homes market was now ‘completely non-functional'” and that only “13,000 mortgages were issued in 2011 compared with 200,000 in 2006”.

A recent Research Technical Paper (12/RT/11) published in November 2011 by the Central Bank of Ireland – The Irish Mortgage Market: Stylised Facts, Negative Equity and Arrears found that:

Approximately 31 per cent of mortgaged properties, or 47 per cent of the value of outstanding loans, are found to be in negative equity at the end of 2010.

It also reports that arrears rates are rising in Ireland.

So while Fama claims that the deregulated financial markets expanded wealth he doesn’t mention that they also destroyed wealth and that process is continuing as governments worsen the financial effects of the crisis by imposing fiscal austerity onto their economies.

It is not that we haven’t been in this territory before – relatively recently.

In Richard Koo’s 2003 book – Balance Sheet Recession: Japan’s Struggle with Uncharted Economics and its Global Implications – which was published by John Wiley & Sons – we learn that after the Japanese property bubble burst in 1990, the fall in asset prices reduced Japan’s national wealth by 41 percent .

Please read my blog – Balance sheet recessions and democracy – for more discussion on this point.

In a recent paper – The world in balance sheet recession: causes, cure, and politics – Richard Koo says:

Japan faced a balance sheet recession following the bursting of its bubble in 1990 as commercial real estate prices fell 87 percent nationwide. The resulting loss of national wealth in shares and real estate alone was equivalent to three years of 1989 GDP. In comparison, the U.S. lost national wealth equivalent to one year of 1929 GDP during the Great Depression …

In spite of a massive loss of wealth and private sector deleveraging reaching over 10 percent of GDP per year, Japan managed to keep its GDP above the bubble peak throughout the post-1990 era … and the unemployment rate never climbed above 5.5 percent.

As I explained in this blog – Historically high budget deficits will be required for the next decade – the reason that Japan continued to grow despite the “massive loss of wealth” is because the government stepped in and maintained the flow of spending.

With the private sector (mainly the corporate sector) reacting to the wealth collapse by shifting from borrower to repayer and the household sector still saving “over 4 per cent of GDP a year”, Koo estimated that without government action, Japan would “have lost 10 per cent of GDP every year”.

We know that the government increased its spending and borrowing and “maintained incomes in the private sector and allowed businesses and households to pay down debt”. As Koo notes, by “2005 the private sector had completed its balance sheet repairs”.

As to Fama’s claim that the recession preceded and caused the financial crisis that is easy to put to rest as a myth.

Did the collapse in the housing market precede the signs in the real economy of a recession?

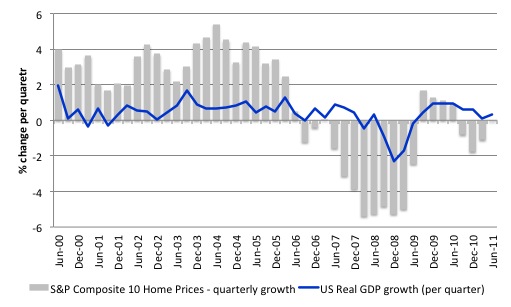

A representative indicator of US residential housing prices is provided by the S&P/Case-Shiller Home Price Indices. I used the seasonally adjusted home price index – Composite-10 and converted the index into quarterly percentage changes to align with the real GDP growth data from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis.

The data is categorical – the housing price bubble burst well before the real economy started to recess. The lag in real GDP growth was of the order of 18 months (6 quarters) after the housing prices started to fall (negative growth in the index).

I could have assembled other indicators to demonstrate the same causality. It is very hard to argue that the financial market implosion was driven by a normal style recession emanating in the real economy. It is impossible for anyone other than a EMH zealot to consider that has empirical (and logical) traction.

I thus have sympathy with the view expressed by Paul Krugman (January 2, 2012) – Hermetic Economic Cults – where he says that the “Chicago guys stopped reading anyone who wasn’t a true believer”.

He concludes that:

So what this whole controversy shows is the insularity of the Chicago guys; their brand of economics has turned into a hermetic cult, closed to any information from heathen sources.

And of course, having tried to pull rank on people who were actually well ahead of them even in terms of fancy modeling, they’re now in a position where they have to become even more hermetic to keep their self-respect.

Much of mainstream economics fits into this “hermetically sealed” category. A denial of facts and a constant restatement of relationships and beliefs that do not accord with the world we live in.

While Berkeley economist, Bradley DeLong ranks Fama among the “Stupidest men alive …” another contender for the “Ostrich award” is the so-called “leading budget analyst” at the right-wing Heritage Foundation – one Brian Riedl.

Given the way this person “understands” the economy it would not really help him much anyway should he take his “head from out of the sand”.

I kept this interview with Mr Riedl (February 3, 2009) – The Case for No Stimulus – which was published in the conservative US Magazine the National Review – because he was so vehement that the fiscal stimulus in the US would be futile and cause interest rates to rise.

Once you read the interview you will wonder about the quality of the job applications to this organisation if they can make him their “leading” analyst.

The Heritage Foundation calls itself a “think tank” and claims that is a “research and educational institution”. That is the first of many lies that comes out of that organisation. There is very little educational content in any of its publications.

Keep in mind that this interview was conducted nearly 3 years ago – so enough time has elapsed for the predictions to “come true”.

The introduction to the article said that the “catch” in the proposal for a US stimulus package was that:

Every penny of such a package must be borrowed, because the government is already running a $1.2 trillion deficit this year and faces a $703 billion deficit for next year …

First, the stimulus could have been accomplished without any borrowing if the US government wanted to change some of its arcane practices which are left-overs from the convertible currency period that collapsed in 1971. The US is fully sovereign, which means it issues its own currency.

Second, under current arrangements (that is, the US governments voluntary choice to issue debt), any deficit – $US1 or $US1.2 trillion would have to be accompanied by debt issuance.

But the aim of the interview is to answer an important question that they said the US debate at that time had ignored: “Where is the money coming from? Can you stimulate the economy by spending money that you must first remove from the economy by borrowing?”.

So that was two questions.

To advance their knowledge they turned to Mr Riedl, who responded:

That is a great question. The grand Keynesian myth is that you can spend money and thereby increase demand. And it’s a myth because Congress does not have a vault of money to distribute in the economy. Every dollar Congress injects into the economy must first be taxed or borrowed out of the economy. You’re not creating new demand, you’re just transferring it from one group of people to another. If Washington borrows the money from domestic lenders, then investment spending falls, dollar for dollar. If they borrow the money from foreigners, say from China, then net exports drop dollar for dollar, because the balance of payments must adjust. Therefore, again, there is no net increase in aggregate demand. It just means that one group of people has $800 billion less to spend, and the government has $800 billion more to spend.

Later in the interview he actually gets confused when asked about the spending multiplier. Far from denying that there is a spending multiplier in excess of 1 he said that the “multiplier is roughly the same regardless of who is spending the money. If you spend the money at a restaurant, you begin the same spending chain as if the government spent the money on someone on unemployment benefits”.

That doesn’t really make sense when juxtaposed with the earlier part of the interview where he is intent on advancing the view that the multiplier is actually equal to zero.

Anyway, it is true that under current arrangements, the US government insists on matching its deficit spending (spending above tax revenue) with an equal issuance of government debt – more or less $-for-$.

The question then arises where did the funds come from that the government borrows. Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) allows us to understand that in an accounting sense, the ‘money’ that is used to buy bonds (that is regarded as ‘financing government spending’) is the same ‘money’ (in aggregate) that government spent.

Another way of thinking about that is that deficit spending creates new financial assets which are available to buy the newly issued government bonds. In this way, the debt issuance really is a monetary operation which drains bank reserves.

What is important to understand is that the purchase (or sale) of bonds by (or to) the non-government sector (domestic or foreign) alters the distribution of assets that are held by the non-government sector.

In that context, it makes no sense to say that government spending rations finite ‘savings’ which could alternatively finance private investment.

As yourself the question – what if the government sold no securities?

The ‘penalty’ for the government that doesn’t pay interest on reserves would be a Japan-like zero interest rate rather than their target cash rate in the absence of some standing facility offering a default support rate for excess reserves.

Should a default support rate be paid, the interest rate would converge on that support rate. Any economic ramifications (like inflation or currency depreciation) would be due to lower interest rates rather than any notion of monetisation.

Remember, bank loans create deposits which borrowers can then use to invest in capital formation (building productive capacity). A credit-worthy borrower is usually able to access loans from the commercial banks which do not need reserves up front in order to type in some numbers to a loan account.

Even if the government bond issue drained the reserves that the initial government spending created (after all the individual transactions in the non-government sector were finalised each day), the central bank is always standing by to provide the desired reserves to the commercial banks to ensure the integrity of the payments system. There can be no shortage of reserves over any relevant period.

That is the way the banks and central bank interact. There can be no squeeze on private investment arising from government borrowing. It just borrows the funds that it created by spending.

Further, the flow of available saving in an economy is never finite. It grows and contracts directly with the growth in national income. Given Mr Riedl conceded that any spending generates a multiplied effect then it follows that total saving in the economy rises as national income expands.

Ultimately, private agents may refuse to hold any more cash or bonds. What would happen then?

The private sector at the micro level can only dispense with unwanted cash balances in the absence of government paper by increasing their consumption levels. Given the current tax structure, this reduced desire to net save would generate a private expansion and reduce the deficit, eventually restoring the portfolio balance at higher private employment levels with lower required budget deficits.

Whether this generates inflation depends on the ability of the economy to expand real output to meet rising nominal demand. The size of the budget deficit doesn’t compromise that and the government would have no desire to expand the economy beyond its real limit.

The interview then moved onto the Mr Riedl’s interest rate predictions. So we are back in the world where evidence is a useful antidote against ideologically-motivated nonsense.

This is what he predicted:

The government is going to have to raise interest rates in order to convince people to lend them the full amount they need. We’re already facing a deficit of $1.2 trillion this year, and 700 billion next year. We borrowed $700 billion for TARP, and now we’re going to borrow $800 billion for this stimulus package. Compare those numbers to the entire public debt, which was 5.8 trillion up until a few months ago. It’s going to be very difficult for a global economy, which is already in a recession, to supply the U.S. government with [$3 trillion] in new borrowing. Right now, a lot of banks are happy to buy Treasury bonds because they are safe investments . . . but overall, that may not be enough. The government may have to raise interest rates higher and higher and higher in order to persuade people to lend their diminishing savings to the government. And that’s going to hurt the economy for a long time.

That is clear enough. As the deficit rises, the government is going to have to “raise interest rates higher and higher and higher” otherwise people will not “lend their diminishing savings to the government”.

First, the national income data shows that as the fiscal stimulus provided support for real GDP growth, total household saving rose and resumed the sort of ratios with disposable income that prevailed before the credit binge (now around 10 per cent of disposable income).

Private corporate profits are now strong and I have noted before that the vast proportion of the stimulus benefits (higher national income) has gone to profits not wages.

But there has not been “diminishing savings”.

Second, any person knows that interest rates in the US came down and have stayed down. Why is that?

The central bank administers the risk-free interest rate and is not subject to direct market forces. While funds that government spends do not ‘come from’ anywhere and taxes collected do not ‘go anywhere’ there are substantial liquidity impacts from net government positions.

Government spending and central bank purchases of government securities add liquidity and taxation and sales of government securities drain liquidity. These transactions influence the daily cash position of the system which on any one day can be in surplus or deficit. The system cash position bears on the central bank’s ability to maintain their desired interest rate and influences its use of open market operations.

Fiscal deficits result in system-wide cash surpluses, after spending and portfolio adjustments have occurred. As commercial banks try to loan these excess funds, downward pressure is put on the cash rate.

Exchanges between commercial clearing accounts do not change the system-wide position. So the central bank must ‘drain’ the surplus liquidity by selling government debt to maintain control over the interest rate.

The central bank’s lack of control over reserves underscores the impossibility of debt monetisation (which is aka as “printing money” in the mainstream literature.

If the central bank purchased securities directly from treasury which then spent the money, its spending would manifest as excess bank reserves. The central bank would be forced to sell an equal amount of securities to support the target interest rate. The central bank would act only as an intermediary between treasury and the public. No monetisation would occur. So Government debt functions as interest rate support and not as a source of funds.

It becomes irrelevant for that function if a support rate is offered to the commercial banks via the central bank standing facilities (as explained above).

Why did Mr Riedl get this so wrong? Answer: because he views the world through the defunct loanable funds doctrine which was demonstrated to be false by Keynes and others in the 1930s. It claimed that the interest rate moved to bring saving and investment into equality. At any point saving was fixed and only changes in interest rates would bring more or less saving into the market as households adjusted their inter-temporal consumption patterns.

Once you realise that saving is a function of income rather than interest rates and saving and investment adjust (within the broader sectoral balances framework) through income changes then you are out of the loanable funds fantasy world and into the real world.

Third, the relevant “interest rates” are the bond yields. Anyone who can click a few links on the Internet and head over the the US Treasury’s debt management section will find the Yield curve data.

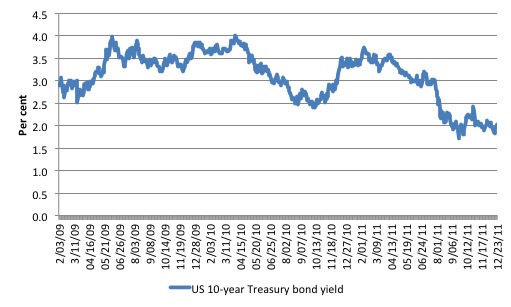

The following graph shows the evolution of yields on US Treasury 10-year bonds since February 3, 2009 (the date that this interview was conducted).

As the deficits have risen, the trend in 10-year bond yields has been down overall.

The yield on February 3, 2009 was 2.89 per cent. The average yield on the 10-year bond over the period February 3, 2009 to December 23, 2011 has been 3.1 per cent and the standard deviation has been 0.54 per cent.

Since that time, the economy started growing more robustly and yields typically rise when times improve because the thirst for risk in the private sector rises.

Even after the ratings agency downgraded the quality of US government debt, the yields fell.

The latest auction data (January 3, 2012) shows the US 10-year bond yield is sitting at the very low rate of 1.97 per cent. The prediction would have better been “falling and falling and falling”.

Conclusion

It is always easier to be wise after the fact. The problem is that Fama and Riedl will always make these sort of systematic errors because they employ a faulty model of how the monetary economy operates.

Until the politicians work that out and stop being pressured by these aberrant views, we will all suffer the macroeconomic calamities that this crisis has wrought.

I have to catch a flight now (I apologise for flying) and so my time is up.

That is enough for today!

Dear Bill

You said that Japan after the collapse of the real estate bubble lost 41% of its wealth. But did it? There was no tsunami or other natural disaster that destroyed 41% of all capital goods in Japan. I think that we should start using a wealth deflator, just as we use a GDP deflator to convert nominal GDP into real GDP.

To illustrate this, let’s assume that Ruritania has 12 million people and 4 million houses. The average price of a house is 150,000. Total housing wealth is then 600 billion, and per capita it is 50,000. Now, 15 years later, Ruritania has 15 million people, 5 million houses, and each house has a market value of 300,000. Total nominal housing wealth is now 1.5 trillion, and per capita it is 100,000. However, real housing wealth is only 750 billion, and per capita it is still 50,000. The population/houses ratio is still 3/1. The ruritanians as a group didn’t become richer. I’m of course implicitly assuming that the 1 million new houses are on average of the same size and quality as the previous 3 million.

We know that consumer price inflation by itself doesn’t make a country either richer or poorer because for every price there is a payor and a recipient. Similarly, asset price inflation doesn’t make a country richer. It only distributes wealth from those who owned the assets early to those who come later.

Regards. James

Bill, I agree with your disparaging comments on the Heritage Foundation and Brian Riedl. However I think there’s a slight flaw in your own analysis of deficits, government borrowing, etc as follows.

You argue, far as I can see, that the money used to buy government bonds originally came from government. Therefore, the latter purchases do not constrain private sector lending to other private sector entities, and do not tend to raise interest rates.

My view is that those purchases do constrain private sector lending and do tend to raise interest rates. However, the circumstances in which governments run deficits (i.e. a recession) are circumstances in which the last thing they are likely to do is to let interest rates rise. Indeed, they are more likely to cut interest rates. And interest rates are cut by having the central bank print money and buy government debt. And that, I suggest, is why there is no observable tendency for interest rates to rise when governments do a standard Keynsian “borrow and spend” exercise.

Bill –

But as that is based on a myth, wouldn’t a better name for it be the Österreich award?

Ostriches don’t bury their heads in the sand, but Austrians do!

Brian Reidl is a total idiot. When I had my radio show several years back I brought him on as a guest and debated these concepts. Nothing has changed.

Even if it were true that deficit spending merely “transfers money from one group to another” (which is not true under fiat regimes) then it would still serve a purpose; that purpose being countering the savings “leakage” to demand. As the late William Vickrey noted: “deficits, sufficient to recycle savings out of a growing gross domestic product (GDP) in excess of what can be recycled by profit-seeking private investment, are not an economic sin but an economic necessity.”

That Eugene Fama. Wow. He’s like that family member that you don’t want to introduce people because they might say something weird and inappropriate. If he keeps talking like that in public he might find himself in a spot of bother…

Very good post Bill and I would not have anything meaningful to say even if I was in a bad mood and I wanted to pick on you. 🙂 Regardless of that, before your status was always reading, now you are calm. I guess you’ve read enough already.

Seriously, you are doing great work! Very good MMT site because you can point readers here and say: hey, that’s been addressed, read that!

Best wishes!

Dear Professor Mitchell,

You keep on referring to “mainstream economists” and you associate various silly behaviour with this term. What is “mainstream economics” is a subject of debate among academic economists, particularly in an era where early specialisation is becoming the norm, possibly due to the demand for ‘papers’. I wonder how the blog reading public understands this term? (Anything other than what Bill Mitchell says?)

It is clearly not true that mainstream economists “… make categorical statements such as – rising budget deficits will push up interest rates and choke off private spending.” Mainstream economists (ie those with a thorough and broad education, including mathematical economics) make conditional statements (theoretical) or contextual statements (ie when in their opinion the empirical conditions sufficiently closely approximate the theoretical conditions.) I would concur that ‘some economists’, particularly those who promote one or another ‘school of thought’, at times make categorical statements.

Yes, in a scientific sense evidence is an antidote to dogma. It is a necessary but not sufficient condition. To be sufficient, the evidence has to have certain qualities. Moreover, as Christopher Monckton, Lord, keeps on demonstrating, not everybody takes note of the scientific method.

The applicability of the scientific method in economics has severe limitations. I assume we agree on this. Nevertheless, there are related methodological issues, which IMHO, are relevant to the topic of this thread.

To illustrate my point, I use your reference to Eugene Fama and the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH). Historically, the EMH gained popularity because, in contrast to contemporary mainstream economics, the EMH proponents skipped the then available analytical methods in economics (1970s) and went for empirical hypothesis tests- volumes of publications. This “Modern Finance” methodology was, to the best of my knowledge, first criticised by an economic mainstream theoretician (math-econ), Professor Beth Alan, who managed to get it published in the Journal of Finance. The EMH was pulled to pieces in a series of papers by mainstream economic theoreticians, including Professor Martin Hellwig, who worked in the area of ‘fully revealing rational expectations equilibrium models’. The impact of the dogma was so severe and worrisome to mainstream economists that one research group, under the leadership of Professor Volker Boehm, investigated the probabilistic possibility of information being fully revealed in prices, using simulation methods (measure zero). I don’t know how many mainstream economists worked in various ways against this dogma that was allegedly supported by voluminous empirical research evidence. But I know my 1996 small contribution on the testability of Fama’s EME hypothesis (not refutable, therefore not testable) was rejected by the Journal of Finance a few months before the 1987 stock exchange crashes in many countries. A few years later I leanred another Australian mainstream economist had reached a similar conclusion and his work was also not published.

Another ‘school of thought’ example of methodological problems is, again IMHO, found in monetarism as well as in ‘naïve market economics’ (locally known as economic rationalism, neo-liberalism – previously Thatcherism, Reaganomics and supply-side economics mixed in somewhere). These ‘schools of thought’ promoted their policy recommendations, using catch phrases (eg ‘crowding out’, ‘competitiveness’, ‘level playing field’, ‘efficiency gains’, ‘globalisation’, ‘privatisation’, ‘transparency’, ‘accountability’,….) and empirical evidence from a period that is irrelevant as soon as their policy changes are implemented (ie the post WWII period).

Professor Mitchell, I would be most grateful if you were to clarify whom you have in mind when you use the term ‘mainstream economists’ and what you have in mind when you use the term ‘mainstream economics’.

As an aside, I like the name of your blog-site.

Correction, paragraph 5, line 5 from the bottom: Please replace “1996” with 1986. Apologies.