I am travelling today to Tokyo and have little time to write here. But with…

Australia – external sector continues to drain growth

A lot of readers write in asking what about external balances – what they mean etc. They are also sometimes puzzled why I say that the external sector in Australia is currently (and typically) draining real growth in the economy when at the same time they read that the terms of trade are at record levels and that we are in the midst of a “once-in-a-hundred-years” mining boom which is reshaping our economy. So today’s release by the ABS of the latest (September quarter 2011) – Balance of Payments and International Investment Position, Australia – provides me with a platform for a brief (I promise) explanation of these concepts and how they might be interpreted from a Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) perspective. The bottom line is that for Australia, our external sector continues to drain growth.

While the following link takes you to the Balance of Payments and International Investment Position, Australia: Concepts, Sources and Methods – the principles that are outlined there are common across all economies (although some of the terminology might differ).

The ABS follows the “internationally accepted standards coordinated by the IMF. The full IMF BOPS Manual is worth reading if you are unsure of the concepts.

The Balance of Payments and International Investment Position accounting structures feed into the System of National Accounts 2008.

I should add that writing these types of blogs also somewhat advances the macroeconomics textbook that I am writing with Randy Wray. So there is a payoff in that respect for the time taken.

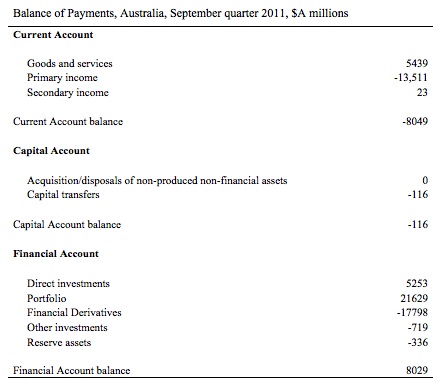

The summary results from today’s ABS release were:

- The current account deficit, seasonally adjusted, fell $A1,023 million (15 per cent) in the September quarter 2011. The surplus on the balance of goods and services rose $A583 million (9 per cent). The primary income deficit fell $A420 million (3 per cent).

- In seasonally adjusted chain volume terms, the deficit on goods and services rose $A1,930 million (17 per cent).

What does that mean? The most significant thing is that when tomorrow’s National Accounts data is released by the ABS for the September 2011 quarter it will show that the external sector has drained real growth by 0.6 per cent. That is, the external sector is a contractionary force.

This should also be put in context of last week’s “mini-budgets” announced by the Australian Treasurer in the form of the Mid-year Economic and Fiscal Outlook 2011-12 (November 29, 2011). Please read the following blog – Autumn or Spring – the madness continues – for a discussion of that announcement.

The fact is that while the Australian government is hell-bent on reducing its deficit to ensure it is in surplus next year, the other macroeconomic sectors – the external and private domestic – are not exactly playing ball. Which should tell the Government something but it seems to have been lost in their ideological blindness.

While private capital formation is strong (associated with large mining infrastructure projects), the household saving ratio has been rising and there remains an unwillingness to return to the pre-crisis consumption growth (which was fuelled by an unsustainable escalation in private debt).

Add in the fact that the external sector is draining demand overall then you might wonder about the logic of the government sector wanted to undermine aggregate demand growth especially when broad labour underutilisation rates stand at around 12.5 per cent with updated numbers coming soon.

Then we add in the latest news from Asia where reports are saying that the “Asian Development Bank has trimmed its 2012 growth forecast for emerging East Asian economies including China, as the eurozone turmoil threatens to drag the global economy back into crisis”.

The Sydney Morning Herald (December 6, 2011) has a story – East Asian economies facing euro headwinds – which reports that the ADB has:

… mapped out an “extreme scenario” of European and US meltdown, which could shave 1.2 per cent off growth next year in East Asia including Japan, from a forecast 5.4 per cent to 4.2 per cent … The worst-case scenario is for both the US and eurozone to fall back into recession, pushing the global economy into a deep slump …

This has direct implications for Australia’s external sector on both the price (terms of trade) and volume (actual real goods and services exported) which will further undermine our national growth rate.

Which is one of the reasons that the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) cut interest rates again today. In the official statement by the RBA Governor we read:

… the Board decided to lower the cash rate by 25 basis points to 4.25 per cent, effective 7 December 2011.

Growth in the global economy has moderated this year after a strong performance in 2010 … China’s growth has been slowing … Trade in Asia is now, however, seeing some effects of a significant slowing in economic activity in Europe. The sovereign credit and banking problems in Europe, to which European governments are still seeking to craft a full response, are likely to weigh on economic activity there over the period ahead …

So overall some “headwinds” from abroad which the RBA believes will moderate the inflation risk in Australia.

Now has does that all fit in with an interpretation of what is going on in the external sector for Australia?

The broadest external account is the Balance of Payments which the IMF Manual describes as:

The balance of payments is a statistical statement that summarizes transactions between residents and nonresidents during a period. It consists of the goods and services account, the primary income account, the secondary income account, the capital account, and the financial account.

So there are several accounts that constitute the Balance of Payments and these accounts can be disaggregated further:

1. Current Account:

1a. Balance on goods and services (“the balance of trade”)

1b. Primary income

1c. Secondary income

The IMF say that the “current account shows flows of goods, services, primary income, and secondary income between residents and nonresident”.

Further, the “current account balance shows the difference between the sum of exports and income receivable and the sum of imports and income payable (exports and imports refer to both goods and services, while income refers to both primary and secondary income).”

2. Capital Account

The IMF say that the “capital account shows credit and debit entries for nonproduced nonfinancial assets and capital transfers between residents and nonresidents. It records acquisitions and disposals of nonproduced nonfinancial assets, such as land sold to embassies and sales of leases and licenses, as well as capital transfers, that is, the provision of resources for capital purposes by one party without anything of economic value being supplied as a direct return to that party”.

3. Financial Account

The IMF say that the “financial account shows net acquisition and disposal of financial assets and liabilities”.

There were some concepts that need explaining which I will return to.

Overall, when the current account is in deficit the economy is net borrowing from the rest of the world – tapping foreign savings. Similarly for the capital account. The sum of the two equals the net balance on the financial account – which thus summarises the net lending (borrowing) position of the nation with respect to the rest of the world.

To give us a reference point, I compiled the following table from the September quarter 2011 ABS Balance of Payments. It shows the broad component accounts and the balances.

Australia is an importer of capital and so accumulates liabilities in terms of interest and dividend payments to the rest of the world.

If you look at the financial account you will notice categories like direct and portfolio investments. Direct investments are in productive equipment, infrastucture etc while portfolio investments are in shares, derivatives and are in my view mostly unproductive and would be declared illegal in a perfect world where financial stability was foremost in the policy makers priorities.

The point though is that these flows of investment then generate income flows in the form of interest, income on equity and other income.

Australians also receive income flows for investments they make abroad but these are swamped by the repatriations we make to foreigners.

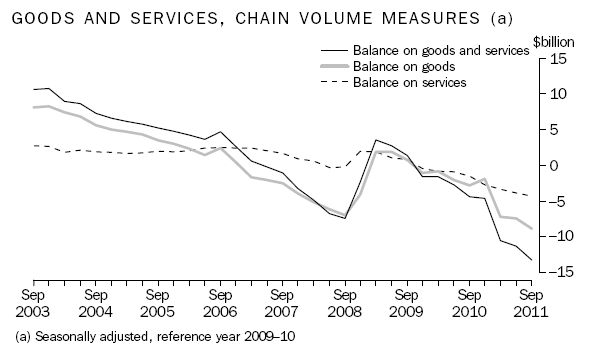

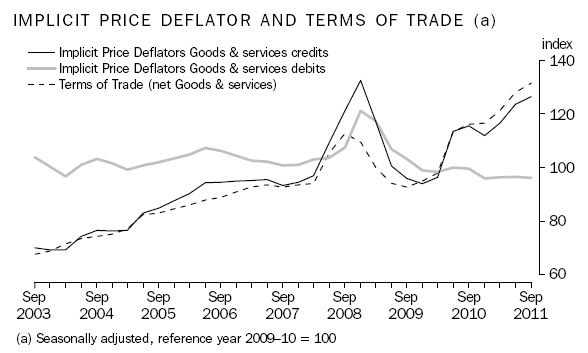

To examine the current account in more detail and to help address the quandary that people are in when they hear me say the external sector drains demand yet the terms of trade is at record levels consider the following graphs.

The first graph (taken from the ABS Publication – Balance of Payments and International Investment Position – shows the seasonally adjusted real balances for goods and services to September quarter 2011. The deficits has been growing. The ABS estimate that in:

… volume terms, is expected to detract 0.6 percentage points from growth in the September quarter 2011 volume measure of GDP …

To clarify, economists talk about current price series and real (constant) prices series. The current price series are self explanatory and refer to the market prices that are prevailing at the time of the transaction. However the total value of the transaction is a mixture of the price and quantity (volume) and over time GDP at market (current) prices might rise by 3 per cent per annum but if inflation is running at 3 per cent then the economy has stood still in real terms (that is, how much was actually produced).

At any rate, volumes are declining on both goods and services (for temporary reasons relating to the difficulties coal production has faced after the floods earlier in the year, and for other more substantive reasons).

To overcome this problem of interpretation, real (or chain-volume) measures of activity are devised whereby the original current price series are deflated (divided by) special measures of price change. So in the above simple case, real GDP growth would be recorded as zero even though nominal (market price) growth was 3 per cent.

The next graph (also taken from the ABS publication) shows the terms of trade which the ABS says are “were the highest on record” in September quarter 2011. So we are getting record prices (relative) for our exports which adds to national income. But exports volumes (goods and services) are being outstripped by import volumes.

The balance between the volume and price movements for goods and services produced a record-high surplus of $A6.8 billion (current prices) which adds to national income (and aggregate demand).

So that is the “mining boom” (record terms of trade) effect.

However, the income drain from the Primary Income payments more than offsets that surplus to generate an overall Current Account deficit. That is the context in which the external sector is draining income from the economy.

Does that matter?

In this blog – Do current account deficits matter? – I discuss that issue from an MMT perspective.

In MMT, a current account deficit attracts no particular importance. However there are some interesting points to make.

First, focusing on the volume side – real goods and services, it is clear that for an economy as a whole, imports represent a real benefit while exports are a real cost. Net imports means that a nation gets to enjoy a higher living standard by consuming more goods and services than it produces for foreign consumption.

Further, even if a growing trade deficit is accompanied by currency depreciation, the real terms of trade are moving in favour of the trade deficit nation (its net imports are growing so that it is exporting relatively fewer goods relative to its imports).

So at present, Australia is sacrificing real resources and getting less back in real terms. It might be argued (and I would probably agree) that the export is a cost, imports a benefit equation is dependent on the composition of each.

Australia is a primary commodity exporter and is sometimes referred to a “big hole in the ground”. The mining sector operates in the outback – remote and distant from the main population. The extent to which the exports are a “sacrifice” is arguable. But then I also sympathise with the view that we should evaluate that in broad terms.

So for indigenous Australians who live in the mining areas and have had a very long historical attachment to the ground and for our environmental concerns it is highly likely that the sacrifices to mining exports are large.

Second, the Current Account balance is really being driven (and always has) by the Primary income payments (net to foreigners). This raises all sorts of questions about foreign ownership and resource sovereignty and the like. MMT doesn’t have a “view” on that but I recognise the debate.

The repatriation of income issue is particularly pertinent for nations like Ireland.

Third, Current Account deficits reflect underlying economic trends, which may be desirable (and therefore not necessarily bad) for a country at a particular point in time. For example, in a nation building phase, countries with insufficient capital equipment must typically run large trade deficits to ensure they gain access to best-practice technology which underpins the development of productive capacity.

A current account deficit reflects the fact that a country is building up liabilities to the rest of the world that are reflected in flows in the financial account. While it is commonly believed that these must eventually be paid back, this is obviously false.

As the global economy grows, there is no reason to believe that the rest of the world’s desire to diversify portfolios will not mean continued accumulation of claims on any particular country. As long as a nation continues to develop and offers a sufficiently stable economic and political environment so that the rest of the world expects it to continue to service its debts, its assets will remain in demand.

However, if a country’s spending pattern yields no long-term productive gains, then its ability to service debt might come into question.

Therefore, the key is whether the private sector and external account deficits are associated with productive investments that increase ability to service the associated debt. Roughly speaking, this means that growth of GNP and national income exceeds the interest rate (and other debt service costs) that the country has to pay on its foreign-held liabilities. Here we need to distinguish between private sector debts and government debts.

The national government can always service its debts so long as these are denominated in domestic currency. In the case of national government debt it makes no significant difference for solvency whether the debt is held domestically or by foreign holders because it is serviced in the same manner in either case – by crediting bank accounts.

In the case of private sector debt, this must be serviced out of income, asset sales, or by further borrowing. This is why long-term servicing is enhanced by productive investments and by keeping the interest rate below the overall growth rate. These are rough but useful guides.

Note, however, that private sector debts are always subject to default risk – and should they be used to fund unwise investments, or if the interest rate is too high, private bankruptcies are the “market solution”.

Only if the domestic government intervenes to take on the private sector debts does this then become a government problem. Again, however, so long as the debts are in domestic currency (and even if they are not, government can impose this condition before it takes over private debts), government can always service all domestic currency debt.

You will also observe from the Table above the size of the portfolio investment flows on the Financial Account. How productive these are in terms of advancing the welfare of Australians is highly questionable.

Overall, MMT highlights that fact that a Current Account deficit can only occur if the foreign sector desires to accumulate financial (or other) assets denominated in the currency of issue of the country with the deficit. It is always better if this deficit is accompanied by a trade deficit.

Then we know that the foreign country is depriving their own citizens of the use of their own resources (goods and services) and net shipping them to the country that has the trade deficit, which, in turn, enjoys a net benefit (imports greater than exports). In this context, a Current Account deficit means that real benefits (imports) exceed real costs (exports) for the nation in question.

So a Current Account deficit will persist (expand and contract) as long as the foreign sector desires to accumulate local currency-denominated assets. When they lose that desire, the deficit gets squeezed down (to zero perhaps). This will almost certainly be painful for a nation, especially if it is enjoying a balance of trade deficit.

The adjustments can sometimes happen quickly which intensifies the pain.

But the overall point for Australians is that while we are enjoying record terms of trade and massive investment in infrastructure to service the external demand for our commodities, the external sector overall is still a negative force on aggregate demand in real terms.

Conclusion

Not much time today!

Tomorrow the National Accounts come out and I will report on them. By Friday the Euro cabal will deliver their latest stunt and we can examine that. Many people have written to me asking about debt brakes. Brakes are good on cars but should not be imposed on fiscal policy – more later on that.

Tomorrow and Thursday I am hosting the Annual CofFEE Conference (aka the 13th Path to Full Employment Conference/18th National Unemployment Conference) in Newcastle. So I will have limited time to write.

That is enough for today!

“Overall, MMT highlights that fact that a Current Account deficit can only occur if the foreign sector desires to accumulate financial (or other) assets denominated in the currency of issue of the country with the deficit. It is always better if this deficit is accompanied by a trade deficit.”

Not sure about “only”.

That is with the assumption (among many others) that all of the deficit can be financed entirely by borrowing in the domestic currency.

A deficit in the current account can also be financed by sale of assets denominated in foreign currency and/or borrowing in foreign currency.

Professor, I am having trouble with the arithmetic. You state:

“Overall, when the current account is in deficit the economy is net borrowing from the rest of the world – tapping foreign savings. Similarly for the capital account. The sum of the two equals the net balance on the financial account – which thus summarises the net lending (borrowing) position of the nation with respect to the rest of the world.” This is in line with the IMF BOPS manual. However, per your BOP table:

a. The financial account categories sum to 25,827 $A (millions), not 8029 as given in the table;

b. In either case the financial account does not equal the sum of the current account plus the capital account (-8049 plus -116, or -8165 $A (millions)).

Dear Tom MH (at 2011/12/07 at 2:07)

Thanks very much for your comment. In my haste yesterday I didn’t include one element of the Financial Account – which relates to Financial Derivatives outflows (-$A17,798 million) which includes the foreign borrowing by our financial institutions (banks etc).

The arithmetic is now consistent. I have updated the Table accordingly to reflect this. Sorry for confusing you.

best wishes

bill

Thanks, Bill. And let me say that this is one of my favorite Econ blogs – please keep up your good efforts!

for all that is bad in financial journalism, on the other hand, check out Kohler “Beware of Bond Vigilantes”. I think it’s Business Spectator (it was sent to me). Excruciating.