I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Time to end the deficits are bad/surpluses are good narrative

Where will the growth come from?

The fiscal policy debate keeps harking back to the 10 out of 11 year surpluses that were achieved by the conservatives in Australia between 1996 and 2007. In a way this short period of history now is represented as the norm and deficits are vilified as being dangerous departures from that norm.

From an historical perspective nothing could be further from the truth. National governments have generally run deficits for two reasons: (a) net exports rarely contribute to growth; (b) the private domestic sector’s overall saving has to be supported.

When the government doesn’t undertake this “income supporting” role, the economy goes into decline.

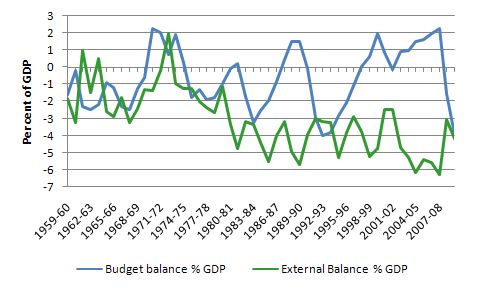

The following graph is taken from the RBA statistics and Budget Papers shows the Budget Balance (deficit -ve) as a per cent of GDP (blue line) against the External Balance as a per cent of GDP (green line) since fiscal year 1959-60.

The external balance is mostly negative throughout this period. That is undeniable.

Each time the budget went into surplus, a recession followed soon after. The long period of budget surpluses between 1996 and 2007 was made possible because households and firms maintained their spending by increasingly indebting themselves – which was also abnormal in historical terms and clearly unsustainable. The GFC is evidence that a growth strategy built on that sort of spending is not capable of underpinning prosperity.

On the economic front, inflation is this nation’s most menacing enemy. We aim to curb it. Unless this aim is achieved, the nation’s productive capacity will run down and job opportunities will diminish … Our present level of unemployment is too high. If we fail to control inflation, unemployment will get worse … It is inflation itself which is the central policy problem. More inflation simply leads to more unemployment … It is not possible to provide more and more government services or transfer payments from the Budget without ultimately having to pay for them through cutting back after-tax earnings via increased taxes.Anyway, in the 2011-12 Budget Paper No 1 you come across Statement 7: Asset and Liability Management. Thanks also to Neil for emphasising this Statement. As the title suggests, it discusses the handling of government debt and other liabilities. You read a lot of self-praise from the Government for delivering a net debt position that is “extremely low by international standards” and that “(t)his stands in sharp contrast to the strength and resilience of the Australian Government’s financial position”. Further, you read that:

Not only are the Government’s debt levels extremely low by international comparison, the expected return to budget surplus in 2012-13 means that the Government is well placed to reduce net debt. A return to budget surpluses will strengthen the balance sheet further, thereby ensuring Australia continues to have the flexibility to respond to any unanticipated future events that have a fiscal impact.It is clear that a sovereign government’s ability to “respond to any unanticipated future events that have a fiscal impact” is not dependent on its level of net debt. The capacity to respond is definitional – that is, if a government issues its own currency and doesn’t take on debt denominated in a foreign currency then it always can buy anything that is available for sale in its own currency. That doesn’t mean it should always exercise that capacity. But it has it whether it has run deficits or surpluses in the past and whether it has accumulated debt liabilities. But I want to focus on the first part of that quote – that running surpluses will leave the Government “well placed to reduce net debt” levels. This leads to a section under Statement 7 entitled Future of the Commonwealth Government Securities Market. Here is an edited version of that section:

During the global financial crisis, the stresses confronting financial markets around the world were unprecedented. The crisis led to significant disruption to capital flows, difficulties in pricing and hedging risk, and a general flight of investors to high-quality, safe-haven assets … the continued functioning of a liquid, AAA-rated Commonwealth Government Securities (CGS) market through this period was critical to managing risk and retaining confidence in Australian financial markets. … In 2002-03, the Review of the Commonwealth Government Securities Market was undertaken in response to concerns about the future viability of the declining CGS market. Since this review, successive governments have committed to retaining a liquid and efficient CGS market to support the three- and ten-year Treasury Bond futures market, even in the absence of a budget financing requirement.The term “budget financing requirement” is highly misleading. It is not a financial requirement that is intrinsic to the monetary system. It is a voluntarily imposed rule that the government issue debt to match its deficit spending. The rule could be abandoned at any time without any change in the government’s capacity to spend resulting. I have also written about the 2002 Review mentioned in past blogs. In effect, the Commonwealth government was retiring its net debt position as it ran surpluses and were pressured by the big financial market institutions (particularly the Sydney Futures Exchange) to continue issuing public debt despite the increasing surpluses. At the time, the contradiction involved in this position was not evident in the debate. We were continually told that the federal government was financially constrained and had to issue debt to “finance” itself. But with surpluses clearly according to this logic the debt-issuance should have stopped. While the logic is nonsense at the most elemental level, the Treasury bowed to pressure from the large financial institutions and in December 2002, Review to consider “the issues raised by the significant reduction in Commonwealth general government net debt for the viability of the Commonwealth Government Securities (CGS) market”. I made a Submission (written with my friend and sometime co-author Warren Mosler) to that Review. The Treasury’s (2002) Review Of The Commonwealth Government Securities Market, Discussion Paper claimed that purported CGS benefits include:

… assisting the pricing and referencing of financial products; facilitating management of financial risk; providing a long-term investment vehicle; assisting the implementation of monetary policy; providing a safe haven in times of financial instability; attracting foreign capital inflow; and promoting Australia as a global financial centre.That is the logic noted above that during the GFC, the liquid and risk-free government bond market allowed many speculators to find a safe haven. Which means that the public bonds play a welfare role to the rich speculators. The Sydney Futures Exchange Submission to the 2002 Enquiry considered these functions to be equivalent to public goods. It was very interesting watching the nuances of the federal government at the time. On the one hand, it was caught up in its ideological obsession with “getting the debt monkey off our backs” – which was tantamount to destroying private wealth and income streams and forcing the non-government sector to become increasingly indebted to maintain spending growth). But it was also under pressure to maintain the corporate welfare. There was no public goods element to the offering of public debt. The argument from the financial institutions amounted to special pleading for sectional interests. Private markets under-produce public goods. When economic activity provides benefits beyond the space defined by the immediate ‘private’ transaction, there is a prima facie case for collective provision. If CGS markets could be shown to produce public goods that enhance national interest, which cannot be produced in any other (more efficient) way, then this would be a strong, pro-CGS argument. But we argued in our submission that: (a) the benefits identified by Treasury which are used to justify the retention of the CGS market can be enjoyed without CGS issuance; and (b) more importantly, these benefits cannot be conceived as public goods, and rather, at best, appear to accrue to narrow special interests. While the maintenance of financial system stability meets the definition of a public good and is the legitimate responsibility of government, the roles identified by IMF (in the paper – IMF (2002) The Changing Structure of the Major Government Securities Markets: Implications for Private Financial Markets and Key Policy Issues, Chapter 4), the Treasury and SFE Discussion Papers among others for the CGS market are not justifiable on public good grounds. We also argued that:

They appear to be special pleading by an industry sector for public assistance in the form of risk-free CGS for investors as well as opportunities for trading profits, commissions, management fees, and consulting service and research fees. Furthermore, and ironically, their arguments are inconsistent with rhetoric forthcoming from the same financial sector interests in general about the urgency for less government intervention, more privatisation (for example, Telstra), more welfare cutbacks, and the deregulation of markets in general, including various utilities and labour markets.We justified this conclusion by closely examining futures markets, the superannuation markets and related issues. It should be understood that CGS are in fact government annuities. We asked the question:

Do the proponents of CGS really want the private sector to have access to government annuities rather than be directing real investment via privately-issued corporate debt, as an example? This point is also applicable to claims that CGS facilitate portfolio diversification. Why would Australians want to provide government annuities to private profit-seeking investors? … We would also require a comparison of this method of retirement subsidy against more direct methods involving more generous public health and welfare provision and pension support.So the continued issuance of debt despite the Government running surpluses was really a form of “corporate welfare” – to provide safe investment vehicles to private investment banks. We argued that all the logic used by the Government in the Treasury Discussion Paper applies only to a fixed exchange rate regime. With flexible exchange rate, where monetary policy is freed from supporting the exchange rate, there is no reason for public debt issuance. We argued that in this context the real policy issue was how well the Government was performing relative to the essential goal of full employment. We concluded the macroeconomic strategy had failed badly. So you will see that 9 years ago we were predicting today’s mess (in actual fact I have writing going back to 1996 predicting the crisis). This is how we put it:

Despite the government rhetoric that the “strategy has contributed to Australia’s sound macroeconomic framework and continuing strong economic performance”, the recent economic growth has been in spite of the contractionary fiscal policy. Growth since 1996 has largely reflected increased private sector leveraging as private deficits have risen. Further, the recent ability of the Australian economy to partially withstand the world slowdown is due to the election-motivated reversal of the Government’s fiscal strategy, which generated the first deficit in 2001-02 since 1996-97. A return to the pursuit of surpluses will ultimately be self-defeating. For all practical purposes any fiscal strategy ultimately results in a fiscal deficit as unsustainable private deficits unwind. But these deficits will be associated with a much weaker economy than would have been the case if appropriate levels of net government spending had have been maintained.So the bottom line in this debate (which led to a Treasury Inquiry) was that the demand for continued public debt-issuance even though the federal government was running increasing surpluses appeared to be special pleading by an industry sector to lazy to develop its own low risk profit and too bloated on the guaranteed annuities forthcoming from the public debt. Nothing much has changed in the 9 years since that Review. The current Statement 7 clearly supports the retention of corporate welfare in the form of debt issuance. You read that:

… the Government consulted a panel of financial market participants and financial regulators on the future of the CGS market … The panel underlined the crucial role of a liquid, AAA-rated CGS market and associated futures market during the crisis and supported retaining liquidity in these markets as the primary objective for the CGS market in the future … Maintaining liquidity in the CGS market to support the three- and ten-year bond futures market will continue to be the Government’s primary objective, in particular as Australian banks prepare for the 2015 commencement of the Basel III liquidity requirements. In addition, the Government will: support liquidity in the Treasury Indexed Bond market by maintaining around 10 to 15 per cent of the size of the total CGS market in indexed securities; and continue to lengthen the CGS yield curve incrementally, in a manner consistent with prudent sovereign debt management and market demand … These objectives will mean that at some stage after the budget has returned to surplus, the Government will need to transition from reducing the level of CGS on issue to maintaining an appropriately sized CGS market … To ensure flexibility in implementing the Government’s objectives for maintaining a deep and liquid CGS market, and to meet the Government’s financing needs over the forward estimates, the Government will seek an amendment to the Commonwealth Inscribed Stock Act 1911 to increase the legislative limit on CGS issuance.First, note that the rules pertaining to debt issuance (including whether they issue any) is a legislative matter. A matter of politics and ideology. Second, the decision to maintain a guaranteed pool of welfare for the speculators comes in the same budget as decisions to make it harder for the unemployed and single mothers and other highly disadvantaged Australians to receive the penurious income support provided by the Government. This so-called workers’ government also chose to leave the unemployment benefit at its existing level which is well below the poverty line. Welfare for some (the better off) but not others (the disadvantaged) is a hallmark of this Budget. My Budget Op Ed for Fairfax Here is the text of an Op Ed I wrote today for the local Fairfax newspaper. I had 750 words allocated by the editor. Most people examine the Budget from a micro perspective – who wins, who loses. I start by examining the macro context – are the policy choices good for the economy as a whole. Demystifying a federal budget is not easy. We too often frame the budget in terms of our own household accounts. Economists and commentators continually urge us to do so. But the federal government is not a super-household. It issues the currency we use and so does not have a problem “financing” its spending despite all the scaremongering about the government running out of money. A budget deficit is essential for stable economic growth if the contribution of net exports (the difference between exports and imports) is not strong enough to sustain domestic demand and the private domestic sector is trying to save. We are in that situation at present. A surplus takes purchasing power away from the private spenders and could only be justified if the economy was growing so strongly that it had reached its growth potential. We would know we were at that point if there were very low levels of unemployment (not 5 per cent), zero underemployment (not 7 per cent) and rising inflation driven by wage pressures. None of those signals are observable at present. The slight rise in inflation in recent months is due to external influences which are unrelated to the strength of the domestic economy. Many erroneously think the deficit is the result of a big spending Commonwealth. That is not the case. The official data shows that between 1996 and 2007, the Coalition government on average spent the equivalent of 24.1 per cent of GDP. It was a period of solid economic growth. Since 2007, the Labor government has on average spent 24.7 per cent of GDP. But their period of office has been marked by the worst economic downturn in 80 years. The stimulus measures introduced saved our economy from a serious recession. The Labor government is not a big spender. What about the revenue side? Between 1996 and 2007, the Commonwealth’s revenue take averaged 24.9 per cent of GDP. Very strong credit-driven consumer spending and later Mining boom Mark 1 drove strong growth which fed the government coffers. The legacy of that binge is that households are now carrying record levels of debt and are trying to rein in their past excessive spending habits. ABS data shows that retail sales are contracting. Since 2007 the revenue take has averaged only 23.4 per cent of GDP. The reasons for the decline in revenue are several but the severity of the GFC account for most of it. So, the rising budget deficit was the result of the GFC rather than fiscal abuse. Consider the current state of the economy. Treasury has significantly downgraded the private spending forecasts published in the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook last December. Mining boom Mark 2 is meant to be delivering an avalanche of private investment yet the performance to date has been modest. The revenue forecasts made just six months ago have also been significantly downgraded due to the sluggish recovery. Net exports are still not contributing to real GDP growth. While exports are growing strongly so are imports. So the spending impulse from the export boom is being drained away from local producers by the rising imports. So they can achieve their much-vaunted surplus, the Government’s Budget response to the weaker than expected revenue is to cut spending more than previously anticipated. The “surplus or bust” approach is a triumph of politics over responsible fiscal management. Given the weak private spending, the tightening of fiscal policy announced in the Budget will put further strain on firms and undermine their capacity to create jobs. The Government says that the current weak growth is temporary. Certainly, the Government is banking on a growth burst in the coming year. I think the growth forecasts built into the Budget are too optimistic. In this context, I think the fiscal stimulus is being withdrawn too early. I do not see consumers driving the same sort of growth that was evident when they were bingeing on credit. The pursuit of a budget surplus is really a quest for a political trophy rather than a demonstration of good economic policy. If the Government undermines growth then their quest for surplus will be denied and the political trophy lost anyway. I predict that outcome. Good economic policy should never be driven by inflexible fiscal rules such as “we will deliver a surplus by 2012-13”. Conclusion Tomorrow we get the April Labour Force data from the ABS which will be interesting. Postscript Here is a link – Warning against job cuts – what I was up to in Tasmania yesterday. That is enough for today!]]>

Bill says:

“We were continually told that the federal government was financially constrained and had to issue debt to “finance” itself. But with surpluses clearly according to this logic the debt-issuance should have stopped.”

—

We find this logic or (ideo)logic also in the definition that Bankitalia give about DEBT:

– We can consider debt the sum of liabilities, before (al lordo) possible assets that can reduce the amount of debt. –

This means that, we issue debt, also if we have a surplus. We issue debt always. if we see the balance sheet of Italy, during 2007 we

have a surplus, but there was the same an issue of debt. Italy is a borrower, I know. but the logic ideologic is in a paradoxycal way, the same everywhere. They say, why?

Bill’s answer is really plausible:

So the continued issuance of debt despite the Government running surpluses was really a form of “corporate welfare” – to provide safe investment vehicles to private investment banks.

There’s one point I’d take issue with, Bill, and that is that the current government’s commitment to a surplus is more rhetoric than reality. As you point out, it is based on growth projections that are almost certainly unrealistic, as even Treasury should realize (especially given how far out their estimates for this year and next were even in the mid-year review). I think they are just paying lip service to the deficit Daleks.

Apart from that, a valuable perspective that puts the current popular obsessions in their place.

Bill –

I put it to you that it’s also time to end the surpluses are bad/deficits are good narrative!

You claim:

There are three problems with this:

Firstly the GFC is not evidence of that at all. It was caused by badly targetted investments and misvalued assets in America.

Secondly you’re making the mistake of considering the effects of changes of deficits and surpluses in isolation rather than in combination with interest rate changes.

Thirdly, whether it’s capable of underpinning prosperity is of academic interest only – what actually matters is what’s advantageous.

That would arguably (depending both on interest rates and on what you count as unemployment and underemployment) be true if the skills the people able to work more had matched the skills the employers required. But they don’t, so it isn’t.

Bill,

If the government succeeds and actually runs a surplus, WHO benefits?

Bill,

From your analysis it appears austerity economics is designed by the finance community (from the good ‘ol USA? hence Fox organisation interest in promulgating it?) to ensure when Government’s deficit increases due to lower tax revenues & more welfare payments – then higher interest can be charged to fund it. Money spent in USA on supporting think tanks & crowding out/denigrating true academic research seems to have been a good investment for the mega rich/finance industry.

Latest in UK is that legislation protecting workers is now the problem hindering economic growth – and needs to be revised.

Tasmania looks like my kind of place. What’s the beer like?

“A surplus takes purchasing power away from the private spenders and could only be justified if the economy was growing so strongly that it had reached its growth potential. We would know we were at that point if there were very low levels of unemployment (not 5 per cent), zero underemployment (not 7 per cent) and rising inflation driven by wage pressures.”

I think that scenario is impossible given the proactiveness of the RBA. Indeed, even the sniff of tighter employment and resource usage due to the mining sector sends the Reserve reaching for tighter MP regardless of the fickleness in retail and housing. One would think from their rhetoric that Australia is running at 5% GDP rather than 2.6%.

Clearly the “deficit bad/surplus good” mentality is now firmly rooted all the way through society to the average household…people erroneously associate this to their own fiscal prudence of putting a bit away every pay packet in savings for a rainy day. Clearly we saw this to be a pointless exercise during the GFC as previous surpluses were dwarfed by the immediate deficits and all we achieved was structural weakness in hospitals and education from the Howard Govt’s excessive frugality.

I was staggered that both leaders fought an election on who would achieve the biggest and quickest surplus first.

-n

Isn’t the austerity, surplus program just a part of the vulture capitalist plan. It will stop as soon as they are good and ready. To be dragged out again when the next generation has forgotten.

Manual goes something like this.

1. Blow debt bubble. Sell out at top.

2. Burst bubble. Pocket bailout money.

3. Move into cash, bonds and commodities.

4. Collapse asset prices. Sell commodities and bonds.

5. Buy up distressed assets.

Repeat steps 1 to 5.

“This raises another matter. As I outlined in this blog – The origins of the economic crisis – the neo-liberal era has been characterised by a major redistribution of national income to profits and away from wages. This was accomplished by suppressing real wages growth (via harsh anti-union legislation and entrenched unemployment) well below productivity growth.”

If you use a lower and middle class person’s budget, is real earnings growth actually negative?

“The requirement then was that to maintain consumption, workers had to be given credit.”

So was someone gaining retirement while the workers going into debt were losing retirement?

“What this suggests is that from an economics perspective is that the public debate has to be re-framed to recognise that a fundamental change in mentality is required on behalf of policy makers. Deficits will more often be required than not. They are essential to supporting growth while there are leakages from the expenditure stream via net exports and saving.”

I believe the currency printing entity should run a deficit with currency that has no bond attached so that it is more likely that productivity gains and other things are distributed equally among the major economic entities and equally in time. This should also mean the currency has a better chance of not becoming overvalued.

The problem with gov’t deficits with debt is that savings of the rich = dissavings of the gov’t plus the dissavings of the lower and middle class. That means you have to keep the rich happy so they don’t sell the bonds and want to roll them over. If not, you have the possibility of a lot of medium of exchange as savings being brought to the present forcing up prices.

“Real wages will have to grow more in line with productivity to enable wage-based consumption to foster strong growth rates. That is our historical legacy.”

I’d say you will need to put more people into retirement if you want to keep the labor maket tight enough for real wages to grow in line with productivity, especially if real aggregate demand growth is below real aggregate supply growth and there is enough supply.

Andrew, that was the 19th century model that the modern central bank was supposed to replace that. Ha. The bankers just captured the cb and regulators, as well as the politicians. Without taxing away economic rent, it will be ever the same. Land rent will fund a landed aristocracy, monopoly rent will fund industrial capitalists, and financial rent will fund financial capitalists.