I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

An understanding of MMT can energise the progressive fight back.

I did an interview in August with the Harvard International Review (published by Harvard University). It was finally published yesterday (October 16, 2011) – Debt, Deficits, and Modern Monetary Theory. I consider the principles that are outlined in that interview to provide a sound organising framework for progressive movements aiming to make changes to the current failed systems. I think Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) does provide insights to the general population that are not only obscured by the mainstream media but which if they are broadly understand will empower the 99% to demand governments redefine their roles with respect to the non-government sector. Part of that re-negotiation has to be to reduce unemployment and redistribute national income more equally. We will also be better placed to have a sensible discussion about the human footprint on the planet. The three goals – full employment, reduced inequality and environmental harmony – should be central to the current civic protests (such as OWS). But we also have understand that government has to be involved in the pursuit and maintenance of those goals. The problem is not government but the politicians we elect and the coalition between them and the corporate elites. An understanding of MMT can energise the progressive fight back.

The right-wing News Limited rag, aka our national newspaper – The Australian published an article today (October 17, 2011) – Wall Street occupiers are an insult to the workers. The article was written by Spiked editor Brendan O’Neill who appears to be interested these days in taking the steam out of the left while masquerading as a progressive.

He labels the OWS crew a “gaggle of hipsters and leftists” who have mounted an “obsessively anti-big business protest” but are accepting “the backing of trendy ice-cream company Ben & Jerry’s, which is owned by the vast food conglomerate Unilever”.

The basic conjecture is that the OWS movement:

… claims to speak on behalf of ordinary Americans … Yet, its super-cool members spend most of their time moaning about how ordinary Americans, being a bit dumb, have been “emotionally brainwashed” by “right-wing propaganda”.

Apparently, O’Neill is upset about about what the OWS protesters (those “corporate-hating hipsters”) are wearing and thinks that “(m)ocking anti-capitalist fashionistas is the gift that keeps on giving”.

But his “deeper” thought is that OWS represents:

… the final death agony of the progressive Left.

What we’re witnessing is not the birth of something new, as the occupiers would have us believe, but rather the death of something old – the death of a principled Left that believed in progress and development and in the ability of “the little man” to change his world for the better.

This is because OWS destroys the traditional Left “faith in the working man” which reflected:

… the entire premise of the Left was that this class of people had it in them to shake up and remake the world.

But Occupy Wall Street – which is the modern expression of the Left “has nothing but disdain for what it views as the fat, feckless, Fox News-addicted inhabitants of mass society”.

According to O’Neill, the “East Coast hipsters” are angry middle-class people who exude superiority relative to the “thick, greedy, Foxed automatons who dare to think differently” to them.

He thinks it is an outcry of students who have chosen the wrong courses (without earning capacity) and are now resentful.

The other strand of his argument is that the new Left expression – environmental conservation – is just a rehearsal – a “very public display of middle-class piety, of petit-bourgeois values such as thriftiness and meanness and disdain for the vulgar hordes with their insatiable materialism”. He claims that the old Left wanted to create “a world of plenty, in making more stuff so everyone could live a life of comfort”.

To reinforce the point, he wonders what would happen if one of the old trade union bosses in “the early 20th century” has have asked the workers to “respect nature’s limits!”

While I have some sympathy with the argument that the “latte set” in advanced countries who talk about sustainability and consuming less etc ignore the fact that millions are starving and need to consume more, I think O’Neill fails to recognise the way the left actually handled the politics of their struggle in the early 20th century.

I don’t want to write much here about this but think back to the 1848 Communist Manifesto. In Chapter II. Proletarians and Communists – there is a discussion of how the “Communists stand to the proletarians as a whole” – that is, the Party and the workers generally. This discussion was very influential in Lenin’s later notion of the Vanguard which is outlined in his 1902 pamphlet – What is to be Done?.

In Chapter II we read:

The Communists do not form a separate party opposed to the other working-class parties. They have no interests separate and apart from those of the proletariat as a whole. They do not set up any sectarian principles of their own, by which to shape and mould the proletarian movement.

The Communists, therefore, are on the one hand, practically, the most advanced and resolute section of the working-class parties of every country, that section which pushes forward all others; on the other hand, theoretically, they have over the great mass of the proletariat the advantage of clearly understanding the line of march, the conditions, and the ultimate general results of the proletarian movement.

The immediate aim of the Communists is the same as that of all other proletarian parties: formation of the proletariat into a class, overthrow of the bourgeois supremacy, conquest of political power by the proletariat.

The theoretical conclusions of the Communists are in no way based on ideas or principles that have been invented, or discovered, by this or that would-be universal reformer.

They merely express, in general terms, actual relations springing from an existing class struggle, from a historical movement going on under our very eyes. The abolition of existing property relations is not at all a distinctive feature of communism.

In other words, the “fat, foxed-out” American workers may find it difficult to break out of those patterns without some vanguard movement.

There was always a sentiment in Marxist thinking (the early basis of Leftism) that the workers were limited in their capacities to develop a revolutionary consciousness and think of themselves as the “working class” opposite the capital class. Lenin believed that workers might join unions to fight “local” issues but these “struggles” would not lead to a broader struggle.

So the “vanguard” was the most militant section of the working class struggle that aimed to reorient the debate away from reform (which is what he saw the trade unions as being about) towards fundamental change of the economic system.

If you think about that some more then the concern that the “fat, foxed-out” workers are being bought off by the Murdoch press and limited mass consumption while the banksters take an increasing proportion of real income to play with is not incompatible with the old concerns of the left. How to organise the “brainwashed” was an old discussion.

I see OWS and its derivatives as a cry for change but that change is yet to be defined very well because their is limited educative material from which a comprehensive “manifesto” to guide an alternative economic order could be derived. MMT is the centre of my work but I accept it has – as yet – limited reach in the mainstream “middle-class” world.

I reject O’Neill’s critique that OWS is just a bunch of angry students who have taken poorly designed courses and now cannot pay their debts back. Students, in some ways, can be the most militant and drive social change because they have less to lose in many important ways. I don’t consider the student political leaders to be fonts of wisdom – but their vocal assaults on the world of the adults – provides the matches to start the fire.

The challenge of the intellectuals is to provide the fuel so that the fire burns. That is one of the problems. University academics have become cowed by the increasing managerialism of our sector and the increasing attack on our tenure and working conditions. There has been a growing feeling within universities among academics that they better be careful as to what they say.

I have never supported that caution nor practised it. I went into academic life because I wanted to be free to research what I liked and to say what I liked upon the basis of that research. More academics should be speaking out around the world now providing ideas and concepts for the OWS movement to take forward in a political way.

Which brings me to a book I have been reading by an American academic at Cornell and an IMF Staff Discussion Note (April 8, 2011) – Inequality and Unsustainable Growth: Two Sides of the Same Coin?. A shorter “blog” rendition of the IMF research is to be found in this article – Equality and Efficiency (published September 2011).

The IMF Note investigates whether “societies inevitably face an invidious choice between efficient production and equitable wealth and income distribution”. They want to know whether “social justice and social product at war with one another”. In other words, is there a reliable relationship between inequality and growth?

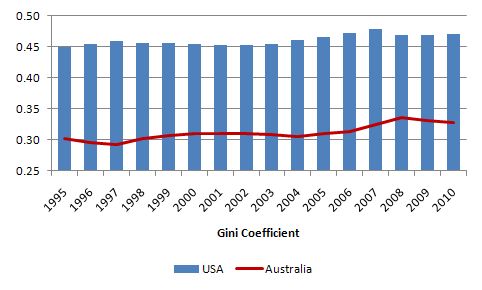

Economists use (among other measures) the Gini Coefficient to summarise the degree of inequality in a nation. It is a relatively simple statistic to understand. It lies between 0 and 1. A value of zero represents absolute equality while a value of 1 represents absolute inequality.

It is derived from a Lorenz curve which plots say the cumulative income distribution by household (or person) in percentiles. So if everyone had the same income, then 1 per cent would have 1 per cent of total, 2 per cent would have 2 per cent and so on. That is the graph would be a straight-line emanating from 0 at 45 degrees.

The more skewed the distribution of income is the more “bowed” the Lorenz curve becomes. The Gini coefficient then summarises the Lorenz curve by dividing the area above the curve and below the 45-degree line by the total area below the 45-degree line. So with perfect equality the numerator would be 0 and so the coefficient would be zero.

A higher number means more inequality.

The following graph shows the Gini coefficient for the US and Australia since 1995. On August 30, 2011, the Australian Statistics Bureau published the most recent – Household Income and Income Distribution, Australia – which is drawn from the Survey of Income and Housing. The data is from that publication.

The US data is from US Census Bureau and related publications.

I also considered the stark inequality in the US in this blog – Some further thoughts on the OWS movement – which provides additional data sources.

I know that there is an issue with producing graphs that do not include zero – but sometimes the message is not distorted if you deviate from that.

It is clear that inequality has been sneaking up in both countries over the period shown. The most recent data will probably show that once the crisis has been ingested inequality will start to rise again.

The trend to increasing inequality is a salient characteristic of the neo-liberal period.

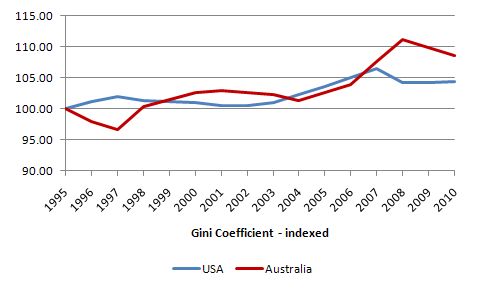

To give you an idea of the changes in inequality in Australia and the US over this period, the following graph indexes the Gini Coefficient at 100 in 1995. You can see that inequality in Australia has been rising faster than in the US over the period shown.

The changing patterns are mostly related to the inability of the lower wage workers to enjoy real wage gains over the period shown. The detailed analysis of the trends way from goods-producing industries (mostly higher wage jobs for lower skilled workers) to service industries (low-wage jobs) and the rising underemployment is the topic of several blogs.

There have also been within-industry shifts which have undermined the conditions for low-skill workers (these include out-sourcing, global shifting, etc).

I read an interesting article once that implicates marriage patterns in the rising inequality. So educated males used to marry their low-wage secretaries. Now they marry their educated female work mates and the secretaries are left to marry low-wage workers elsewhere.

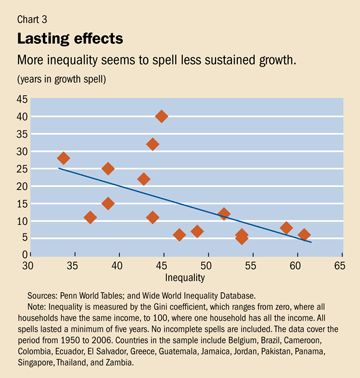

Now what does the IMF say about inequality and growth?

Their summary note says that:

… we discovered that when growth is looked at over the long term, the trade-off between efficiency and equality may not exist. In fact equality appears to be an important ingredient in promoting and sustaining growth. The difference between countries that can sustain rapid growth for many years or even decades and the many others that see growth spurts fade quickly may be the level of inequality. Countries may find that improving equality may also improve efficiency, understood as more sustainable long-run growth.

That is contrary to a lot of the “trickle-down” theory that mainstream economics preaches.

The following graph is taken from the IMF Note (their Figure 2 or Chart 3 in the shorter note). The graph shows “the length of growth spells and the average income distribution during the spell for a sample of countries” where the “a growth spell” is defined “as a period of at least five years that begins with an unusual increase in the growth rate and ends with an unusual drop in growth” and inequality is measured by “the Gini coefficient”.

The IMF paper says that one of the possible reasons “that inequality is strongly associated with less sustained growth” is because it:

… may amplify the potential for financial crisis, it may also bring political instability, which can discourage investment. Inequality may make it harder for governments to make difficult but necessary choices in the face of shocks, such as raising taxes or cutting public spending to avoid a debt crisis. Or inequality may reflect poor people’s lack of access to financial services, which gives them fewer opportunities to invest in education and entrepreneurial activity.

You can see that this conclusion was written by IMF economists. They just cannot help putting in nonsense about debt crises etc although it is true that politicians act as if there are sovereign debt crises which clearly influences the capacity of their economies to absorb a negative demand shock. In other words, by invoking austerity – unnecessarily – they actually undermine growth.

I have in the past emphasised the role that the changing income distribution between wages and profits has played in the crisis. The two points bear repeating. First, the wage share has plummetted in many nations as real wages growth has failed to keep pace with productivity growth. Legislative attacks on trade unions and other welfare-to-work policies have led to this divergence. The question then was how can growth be maintained?

Second, that problem was solved by the growing financial sector need to push credit onto households. Consumption was maintained not through the traditional means of real wages growth but by credit growth. The financial engineers seized on a winner they could keep economic growth going (via consumption) and earn interest on top of it.

The real income that was expropriated by the financial sector came from the redistribution of national income.

The problem with this rising inequality (partly driven by this redistribution of factor shares) was that it could not sustain growth. The rising indebtedness was always going to explode.

If the OWS movement starts to articulate concrete concepts to guide their “revolution” then one of the first principles is that growth should be based on real wages growth not credit growth.

That will make it sustainable and more evenly distributed but will also starve the “banksters” of their gambling chips. The question of how much growth we should have is a separate issue.

Whatever growth there is to be – real income will have to be produced. That should be produced equitably. That should be a growing cry among the “hipsters”.

Now what about that book I was referring to?

The book The Darwin Economy: Liberty, Competition, and the Common Good was recently published (September 21, 2011) by Princeton University Press and was written by Cornell University’s Robert H. Frank.

You can read the introductory chapter HERE and an Op-Ed article in the New York Times (September 17, 2011) – Darwin, the Market Whiz

I cannot say I agree with everything that he writes and in fact I consider his representation of “public finances” to be mainstream and thus incorrect. But the general tenor of the book – emphasising the damage that inequality inflicts on economic prosperity – is well founded and worthwhile.

The Book sets the theme from the outset:

During the three decades following World War II, for example, incomes were rising rapidly and at about the same rate- almost 3 percent a year- for people at all income levels. We had an economically vibrant middle class. Existing roads and bridges were well maintained, and impressive new infrastructure was being added each year … No longer. The economy has grown much more slowly during the intervening decades, and only those at the top of the income ladder have enjoyed significant earnings gains. CEOs of large U.S. corporations, for example, saw their pay increase tenfold over this period, while the inflation-adjusted hourly wages of their workers actually fell. The middle class is awash in debt.

He notes that the “almost completely paralyzed” political system in the US refuse to use the same public funds to provide the same growth in infrastructure which “has been steadily falling into disrepair”.

An exemplification of the failure of the US state is “the stubborn unemployment spawned by the financial crisis of 2008”. His characterisation of the permanent losses that are endured daily by the unemployment is worth noting:

Each new day of widespread unemployment is like a plane that takes off with many empty seats. In each case, an opportunity to produce something of value is lost forever. There was no good reason for failing to take every possible step to avoid such waste. Yet critics of economic stimulus were quick to denounce government spending itself as wasteful, even as a host of useful projects cried out for attention.

He cites government research (Nevada) which shows that “a worn 10- mile stretch of Interstate 80 would cost $6 million to restore if the work were done today; but if we postpone action for just two years, weather and traffic will eat more deeply into the roadbed, and those same repairs will cost $30 million”. That is, quite apart from the issue of how we measure “costs”, austerity is myopic. It takes more real resources to repair vital public infrastructure if it is neglected than if it is maintained sequentially.

I was a PhD student in Britain during Margaret Thatcher’s onslaught on the public sector. The sewers/drains in Manchester collapsed during that time because of lack of maintenance and required much more extensive repair as a result than if they had have maintained the systems sequentially. In the meantime, the inconvenience to the public of the subsequent restoration was a major irritant (and health issue).

Frank also notes that the Austerians don’t even understand the nature of public finances. He cites “credible evidence” that:

… says that each dollar cut from that budget causes tax revenue to fall by $10, for a net increase in the deficit of $9! That such cuts could be approved by the House of Repreentatives suggests that we’re becoming, in the coinage of one pundit, an ignoramitocracy- a country in which ignorance-driven political paralysis prevents us from grappling with even our most pressing problems.

He cites many examples of policy positions that make no sense, even in terms of the “goals” they are aspiring to. That is, if you want to cut the deficit you have to grow the economy. Cutting public spending when private spending is weak is pure ideology.

In this context, I really liked the New York Times Editorial (October 14, 2011) – Britain’s Self-Inflicted Misery – which focused on the vandalism of the British government.

In commenting on the fact that British economic data is uniformly bad at present (and getting worse), the NYT Editorial said:

For a year now, Britain’s economy has been stuck in a vicious cycle of low growth, high unemployment and fiscal austerity. But unlike Greece, which has been forced into induced recession by misguided European Union creditors, Britain has inflicted this harmful quack cure on itself.

Austerity was a deliberate ideological choice by Prime Minister David Cameron’s ruling coalition of Conservatives and Liberal Democrats, elected 17 months ago. It has failed and can be expected to keep failing. But neither party is yet prepared to acknowledge that reality and change course.

Britain’s economy has barely grown since the budget cuts began taking effect late last year. The most recent quarterly figures showed the economy flat-lining, with growth at 0.1 percent.

It added that “(d)rastic public spending cuts were the wrong deficit-reduction strategy for the weakened British economy a year ago. And they are the wrong strategy for the faltering American economy today. Britain’s unhappy experience is further evidence that radical reductions in federal spending will do little but stifle economic recovery”.

I didn’t agree with its further discussion about the need for fiscal consolidation being important in the medium-term but the overall message of the Editorial was sound – that:

Austerity is a political ideology masquerading as an economic policy. It rests on a myth, impervious to facts, that portrays all government spending as wasteful and harmful, and unnecessary to the recovery. The real world is a lot more complicated. America has no need to repeat Mr. Cameron’s failed experiment.

Robert H. Frank seeks to ask whether Adam Smith or Charles Darwin is the “greater economist”. He concludes that it is Charles Darwin despite the adulation by mainstream economists who continually tell us that Smith’s invisible hand – the “unbridled market forces harness self-interest to serve the common good.”

Robert H. Frank concludes that “Darwin understood that individual and group interests sometimes coincide … [but] … also saw that interests at the two levels often conflict sharply. In those cases, he said, individual interests trump”.

His research finds that “Darwin … understood that competition often favored traits that brought misery to all, and he knew animals like elk could do nothing about it. But human beings, who face similar conflicts, have better options”.

He concludes that if we understood these options, we could “resolve a host of seemingly intractable economic problems in the United States, and in nations that have followed our lead”:

Applied properly, it would lead to simple steps that could liberate trillions of dollars in resources each year – enough to end perennial battles over budget deficits, restore our crumbling infrastructure and pay for the investments needed for a sustainable future. No painful sacrifices would be required. No cherished freedoms would be threatened.

He argues that “a few changes in the tax code would suffice” – scrap progressive income tax and implement a progressive consumption tax – is is preference.

I won’t debate his policy suggestions here – another blog. Suffice to say that MMT provides a route whereby governments can ensure that there are no painful sacrifices. Clearly we can understand MMT to be a description of how the monetary system actually operates now – and therefore it provides us with an explanation as to why things turn out the way they do.

But MMT can also free our minds to provide solutions to problems that we have been educated to believe are insurmountable or can only be addressed with fiscal austerity etc. In this way, MMT can be empowering.

It is clear that a currency-issuing government can easily employ all the unemployed. So start with that proposition – it is financially possible. Then start debating the issue at a higher level – how would that happen? How would the organisational structure look? etc. Rather than just being bound by the statement that it would send the government broke.

No it wouldn’t. So an understanding of MMT represents a liberating force as well as a description/explanation of what is.

Robert H. Frank’s policy proposals might be flawed but his logic that increasingly competitive markets – the ideal of the mainstream – are “also hugely more wasteful” – and “actively undermines” common good in favour of individual interest – is well-founded in the data.

His book also helps us understand why inequality is damaging for the very goals that the proponents of inequality aspire to.

He says that until we understand things like that – and ditch the blind (ideological) adulation of Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” (free market):

… the wasteful aspects of the competitive process will continue to impose enormous costs on everyone.

I was interested to read New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof’s article (October 15, 2011) – America’s ‘Primal Scream’ – refer to Frank’s book. The article was trying to understand the OWS movement.

Nicholas Kristof considered:

IT’S fascinating that many Americans intuitively understood the outrage and frustration that drove Egyptians to protest at Tahrir Square, but don’t comprehend similar resentments that drive disgruntled fellow citizens to “occupy Wall Street.”

His interviews “with protesters in Manhattan’s Zuccotti Park seemed to rhyme with my interviews in Tahrir earlier this year” in that they both reflect a frustration with inequality.

In the Middle East case it was an “inequality in the political and legal worlds” whereas in the US the concerns reflected “economic inequity”. He says the rising economic inequality in the US (and elsewhere) has started to raise questions about how the economic system works.

The OWS reflects, in his view, “a growing sense that lopsided outcomes are a result of tycoons’ manipulating the system, lobbying for loopholes and getting away with murder”.

We now have banks that get away scot free “with privatizing profits and socializing risks” which is really “another form of bank robbery”.

He then referred to the The Darwin Economy has showing that:

… among 65 industrial nations, the more unequal ones experience slower growth on average. Likewise, individual countries grow more rapidly in periods when incomes are more equal, and slow down when incomes are skewed.

Which takes him back to OWS which he thinks is echoing the rising inequality which is “a cancer on our national well-being”.

Conclusion

In closing, I hope that the OWS movements does start to articulate some coherent messages rather than just talk about jailing the banksters. I hope they see that government is not the problem per se but it is rather the coalition between government and the elites that is the problem.

I hope they articulate the point that we need radical change – not some local change – some amelioration of inequality or some more regulation. We need a fundamental rethink about the size and role of the financial sector and that can be driven, in part, by a fundamental change in the distribution of national income – back to wages.

That, in turn, will allow growth to be wages-driven rather than credit-driven which will help sustain full employment.

Once we understand how to achieve full employment and put in place a growth strategy that can sustain that we need to define how that growth strategy is consistent with our use of finite real resources.

These steps are not sequential but interactive but I hope the emerging OWS narrative doesn’t throw out the need for economic well-being while striving for its “green” and anti-materialist credentials.

That is enough for today!

Bill,

I know you’re very busy, but is there any chance you might sometime fly to New York and talk directly to the protesters? Or get a colleague in the states to visit them? They really seem desperate for new ideas, and might be one of the few groups in the world whose brains won’t shut down with images of money-filled German wheelbarrows when they hear what you have to say.

If they start something in Brisbane I will definitely go visit them!

You said it correctly when you pointed out that the problem is not government but politicians. Better said, “Mr. Reagan, the problem is not government, but politicians such as yourself.”

But, it might be better to say that the problem is not government, but the system that elects the politicians. Until the system is changed, I can’t see politicians changing. We need to work to change the electoral system.

While O’Neill is possibly the least offensive member of the LM medusa that has spiked as one of its serpentine extensions, its a bit rich taking the OWS folk to task for who he claims they are. Especially from a comfortable News International perch.

But then they do seem to be attacking his organisation’s corporate customers, rather than the hard working folk O’Neill claims.

As Darwinian evolution is mentioned, I can think of few better examples of adaptation to environment than that collection of ex revolutionary communist party members. Perhaps they should heed the man himself:

“if the misery of our poor be caused not by the laws of nature, but by our institutions, great is our sin”

Grigory, Randall Wray and Pavlina Tcherneva were among MMTers who attended OWS on the weekend. They handed out flyers, gave interviews and chatted with fellow occupiers.

(Great interview, Prof.)

I am part of the OWS movement here in Chicago and I intend to form a committee to help educate people on economics, particularly MMT.

My emai is jphoc13@gmail.com and I would love to get in contact with anyone who would like to help or email more educational material on the subject.

The education of MMT into this movementn could start right here.

Bill

Thanks for the post.

It would be good to think that a major economy might re-orient itself and be run recognising the value of MMT by making the type of policy change you have been outlining in your blog. I am assuming that USA will stay firmly in the neoliberal camp.

Could a country like Australia or UK actually make this change alone?

I suspect there would be inevitable attacks on the new policies by the financial markets. The population also would probably not understand at the moment, as they believe government and household economics come from the same same stable, so might well not support the essential changes that would be needed. In-country neoliberal commentators / journalists would also throw themselves into the anti-brigade. So, I reluctantly conclude it might not be done properly, if at all. (If change isn’t implemented properly, it would be a disaster).

The OWS movement, now spreading, provides an opportunity to educate. Could it be that this is an ideal time to press for change amongst any of the more open-minded politicians who can see a new and possibly unstoppable band-wagon?

I wonder if you have any thoughts on a way forward towards any economy based on the ideas you have been putting forward?

Richard1 says: “The population also would probably not understand at the moment, as they believe government and household economics come from the same same stable, so might well not support the essential changes that would be needed.” One way to make the population see the truth is to present actual data in MMT ways. For example, see

http://pshakkottai.wordpress.com/2011/10/16/gdp-plots-from-2000-to-2010/

and

http://pshakkottai.wordpress.com/2011/10/16/us-gdp-vs-govt-spending-2/

which plot GDP in terms government spending and show that in the real US economy government spending and GDP grew in proportion from 1969 to 2010.

Partha shakkottai

“… claims to speak on behalf of ordinary Americans … Yet, its super-cool members spend most of their time moaning about how ordinary Americans, being a bit dumb, have been “emotionally brainwashed” by “right-wing propaganda”.”

I went to the first gathering of Occupy New Hampshire this weekend, and I can attest that most of the people there are hardly super-cool. The group includes unemployed people, the homeless, fixed-income seniors and the low-income working class. There were out-of-work librarians; service workers without health benefits; temp workers; and middle class people frustrated by insecurity and stagnation. Not a lot of hipsters and Kool Kids as far as I could tell.

I take comfort every time I read or see one of these right-wing mouthpieces lashing out in anger, rather than just laughing the movement off. That tells me they are scared and worried about what they are seeing. They’re on the run.

I have also found it necessary in discussions with people in person and in debates on the online forums to take on the Austrians and the Ron Paul minions – who unfortunately our out in numbers selling their ideas to the New Hampshire group. (One Paul enthusiast is even an organizer, and was the only one there with a megaphone.) People struggling to understand what is happening to them economically are vulnerable to these inherently right-wing theories, that try to convince them that the source of all their problems is the government and the Fed, rather than the private sector plutocrats and feudal lords who suck the lifeblood from the 99% through economic rents – at least when the former are not busy crashing the economy with their financial Ponzi schemes.

I agree wholeheartedly that a familiarity with MMT ideas, and skills in working those ideas into the explanations of concrete policy proposals like the job guarantee for full employment, are a big plus for those promoting a progressive and egalitarian agenda. I have already used some of these ideas to great effect.

Could someone direct me to an online source where the job guarantee proposal is explained very concisely? I’m thinking of something suitable to people who are just learning about these ideas for the first time, and who don’t necessarily want to spend much time – at least initially – on the economic theory and MMT framework that helps support it.

@Bill

Apologies to other posters – as off specific topic… but…

Just wanted to say a huge thanks to you Bill. I have been lurking and learning for a couple of weeks now. Your blog is what helps make the Interweb a truly wonderful thing. I just want to join others in thanking you for taking the time to educate. You are an exceptionally good example of that noble breed – the born teacher. Thank you.

Dr. Mitchell:

A fascinating article, and distressing as well, in that we seem to be so unaware of this kind of analysis in our (US) national press. I forwarded a copy on to the Rachel Maddow Show, which has done most of the educational work in cable news these days. I hope they follow it up. In the meantime, it would be good to develop additional graphical presentations of the compelling arguments, to help raise awareness.

I see that CNBC have even picked up the HIA article, and the commentary was complimentary too. This is getting pretty exciting. Looking forward to the numbnut anchors trying to get their head around it, in between screeching rants about government “gettin outta the way!” and the “reduce taxes, increase confidence” malarkey they carry on with.

http://www.cnbc.com/id/44931200

MMT and OccupyWallSt:

Dylan Ratigan on the Political Efforts to Hijack #OccupyWallStreet

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2011/10/dylan-ratigan-on-the-political-efforts-to-hijack-occupywallstreet.html

Great interview with David DeGraw and Prof. Bill Black

Dan Kervick said: “that try to convince them that the source of all their problems is the government and the Fed, rather than the private sector plutocrats and feudal lords who suck the lifeblood from the 99% through economic rents – at least when the former are not busy crashing the economy with their financial Ponzi schemes.”

I don’t see the difference.

savings of the rich = dissavings of the gov’t (preferably with debt) plus dissavings of the lower and middle class (preferably with debt)

While there are certain differences, it is STILL THE DEBT that is problem, whether gov’t or private, because both are owed mostly to the rich and create a time difference between spending and earning with certain assumptions that may not be met.

“Part of that re-negotiation has to be to reduce unemployment and redistribute national income more equally.”

IMO, medium of exchange mistakes of the past need to be corrected so that there are more people in retirement which should reduce unemployment and tighten up the labor market to redistribute national income (real GDP) more equally.

JP Hochbaum, would you be willing to listen to:

current account deficit = gov’t deficit + private deficit + currency printing entity deficit with “currency” and no bond/loan attached

instead of:

current account deficit = gov’t deficit + private deficit

“He says the rising economic inequality in the US (and elsewhere) has started to raise questions about how the economic system works.”

like real GDP should not always grow as fast as real aggregate supply (AS) [there is a demand side]?

“I have in the past emphasised the role that the changing income distribution between wages and profits has played in the crisis. The two points bear repeating. First, the wage share has plummetted in many nations as real wages growth has failed to keep pace with productivity growth. Legislative attacks on trade unions and other welfare-to-work policies have led to this divergence. The question then was how can growth be maintained?”

Run an all “currency” economy with no gov’t debt and no private debt. IMO, that gives the best chances of productivity gains and other things being distributed evenly between the major economic entities and evenly IN TIME. That means the amount of medium of exchange cannot go down because of debt repayment and/or debt defaults.

Stop assuming real aggregate demand is unlimited and/or real aggregate supply can never reach the same level or above real aggregate demand.

Fed Up says: “I don’t see the difference.

savings of the rich = dissavings of the gov’t (preferably with debt) plus dissavings of the lower and middle class (preferably with debt)

While there are certain differences, it is STILL THE DEBT that is problem,…..”

The government owes itself a “debt” which is different from debt owed by middle and lower classes to the rich. government debt is not the problem. Empirical data show that Government spending (deficit or otherwise) and GDP are proportional.

Partha Shakkottai

If public debt is balanced by private income, then why tax at all? Why not simply create more public debt and use reserve accumulation to manage the temperature of the economy?

Reply to Richard Gay: Actually private sector income is four times the government spending (deficit or otherwise), empirically, as shown in my blogs referred to above. The GDP is five times government spending. The reason for the factor of four must be the value added by converting natural resources and labor to more valuable goods. If taxes are totally absent, the incentive to work probably will be greatly reduced. With all the money floating around, money will lose value and inflation might result. I am guessing. It would be useful to model an elementary model economy to see if inflation results.

Partha Shakkottai

Dan Kervick.

http://neweconomicperspectives.blogspot.com/2009/08/job-guarantee.html

I tend to follow the Bill argument to businessmen; what sector are the unemployed in? Answer, the public. Why don’t we get them to do a days work for their benefit, £65.4 in the UK? But why stop there, why not give them 5 days a week work for £327, £17,000 a year? This cost effectively targets demand where it’s needed most. A rising tide lifts the lowest beached boats first. This money would get spent supporting local jobs and businesses and paying off debts so banks are more solvent, as demand increases, businesses would employ more, banks would be more prepared to lend…then we could all do as our Dave Cameron says and pay off our debts/save a cushion for a rainy day.

Then I move on to explain that if the politicians did this automatic fiscal stabiliser extension, they could simply get out of the way and allow the deficit to do it’s job expanding to be equal to net private and foreign saving desires, literally funding those desires. Across a business cycle Americans net save 2% and the foreign balance is 3% so the MEAN deficit is 5%, hence US deficits are normal 85% of the time, a surplus may happen in a boom.

Richard Gray paying taxes anchors people’s currency use and regulates demand against supply.

Bank reserves aren’t a lever in the economy, there are a few posts on that subject.

This is a comment from Darwin, the Market Whiz.

“Because savings would be tax-exempt, the biggest spenders would save more and spend less on luxury goods, leading to greater investment and economic growth, without any need for government to micromanage anyone’s behavior.” ???

And of course today in the UK with the 5.2% inflation rate generally determining next year’s benefit increases, you have a raft of idiot newspapers wondering how the government is going to ‘afford’ these increases – talking about ‘blackholes’ and the like.

When they should be dancing a jig. Finally something has forced the government to up its fiscal interventions – and in the right areas.

John Quiggin has put an extended discussion of MMT and what he suggests are its popular oversimplifications up on his blog this morning.

As Quiggin is one of our most high profile progressive economists and commentators I think it would be a great thing if Bill could engage in the discussion directly and some form of shared position statement was worked out, as it seems clear to me that there are far more agreements than disagreements. As the post title said, it would “energise the progressive fightback” against the current shared neoliberalism of major political parties here.

I think that many rightly perceive institutional solutions to be a major part of the problem.

What is in MMT for this point of view?

I often find myself exasperated by those with what I call “Federal Reserve” or “Fractional Reserve Derangement Syndrome”, but these are the very people that should be low hanging fruit for MMT. They know something is wrong with the institutions, but they’ve latched on to incorrect narratives.

John Quiggin has put an extended discussion of MMT and what he suggests are its popular oversimplifications up on his blog this morning.

As Quiggin is one of our most high profile progressive economists and commentators I think it would be a great thing if Bill could engage in the discussion directly and some form of shared position statement was worked out, as it seems clear to me that there are far more agreements than disagreements. As the post title said, it would “energise the progressive fightback” against the current shared neoliberalism of major political parties here.

You best watch what you ask for, it seems to me that MMT can be used both ways, specifically if you follow its logical conclusion it is a strong argument for the elimination of all taxes, MMT clearly says government doesn’t need taxes to spend. So if its spending is within the bounds of acceptable inflation no taxes are required.

To Jeff65

Reaching the ‘deranged’ fractional-reserve critics would be easier if:

1. You hide the insulting rhetoric and deign for something more benign, and

2. If MMT made more sense from a progressive political-economic perspective, which it doesn’t.

I trust to your understanding that the anti-social nature of fractional-reserve banking, where private individuals usurp the state’s power to create the national medium of exchange through their wealth-creation and concentration privilege, has been under attack at least since the Innesian theory was developed, let alone picked up by this more modern school of thought.

It’s not that we don’t understand money, Jeff. It’s that we do understand it, and, as a result, can’t abide the idea that the banker’s private privilege of creating their own wealth really has any place in modern political-economic thought by progressive-thinking individuals.

Austrian economics pretty much agrees with the MMT construct of the Fed and Treasury being one ‘financial-structural’ entity in order to serve their own political agenda of the holy grail of private property.

Progressives who want to abolish the private wealth creation power of fractional-reserve banking do so because it violates the basic tenets of public purpose government and economic democracy.

So we don’t agree with the MMT premise that the government creates the money.

And THAT is the problem.

The OWS crowd is the one that knows something is wrong.

Progressive full-reserve, public money advocates know WHAT is wrong.

And MMT does not solve for that problem.

Thanks.

JP Hochbaum says: “I am part of the OWS movement here in Chicago and I intend to form a committee to help educate people on economics, particularly MMT.

My emai is jphoc13@gmail… and I would love to get in contact with anyone who would like to help or email more educational material on the subject.

The education of MMT into this movementn could start right here.”

How about a sign that says “Tell ben bernanke and alan greenspan I don’t want a loan. I want a raise.”?

partha shakkottai said: “The government owes itself a “debt” which is different from debt owed by middle and lower classes to the rich. government debt is not the problem. Empirical data show that Government spending (deficit or otherwise) and GDP are proportional.

Partha Shakkottai”

While there are some differences between gov’t debt and private debt, there are still similarities that can make both types of debt the problem. Plus, there are probably other things (medium of exchange, other types of spending, etc.) that are affecting GDP.

partha shakkottai said: “If taxes are totally absent, the incentive to work probably will be greatly reduced.”

Even if taxes are zero(0), I still have monthly budget expenses to meet somehow.

Postkey said: “This is a comment from Darwin, the Market Whiz.

“Because savings would be tax-exempt, the biggest spenders would save more and spend less on luxury goods, leading to greater investment and economic growth, without any need for government to micromanage anyone’s behavior.” ???”

Market Whiz?????

I doubt the biggest spenders would spend less on luxury goods. They like being rich enough to buy them. The other problem is more savings, more investment, more real aggregate supply (AS), and more real GDP. No concept of the demand side. Still living in their 1970’s fantasy world.

Jeff65, your phrases of “Federal Reserve” or “Fractional Reserve Derangement Syndrome” actually mean these people are headed in the right direction, towards the concept of too much debt (whether private or gov’t).

Fed Up and Joebhed,

I ask you what is the significance of the fraction of reserves (whether 0%, 10% or 100%) backing up deposits when reserves now do not represent anything tangible as they once did?

There’s no significance to reserves unless the discount window is closed. And then we’re back to the 19th Century.

The main issue is whether interest is paid on held reserves or whether they are 0% ‘cash ratio deposits’ as we have here in the UK.

There is no difference at all between a fractional system and a reserve expanded system with a discount window. It’s still all down to the amount of ‘credit stock’ the bank can deploy – and that is currently a multiple of its capital.

The issue is simply how much ‘credit stock’ a bank has and is able to deploy, how much ‘credit stock’ the economy needs and how you monitor and control that value. I’m not convinced a fixed centralised credit stock control system is any better than a dynamic decentralised one.

Of course the real beef is with maturity transformation and whether the benefits of that outweigh the risks.

The moral argument doesn’t wash either. Banks make money on the turn. Whether the money is centrally provided or held as dematerialised credit stock the bank’s margin will be the same on the loans advanced.

To Jeff65

The significance of full-reserve banking depends on its context. I have here supported the Kucinich Bill that transforms the private, debt-based, fractional-reserve bank and lending system to one of public money administration, including debt-free issuance, with banks operating on a full-reserve basis.

The full context is again here as proposed in H.R. 2990.

http://www.monetary.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/HR-2990.pdf

I have no idea what you mean by your claim that “reserves do not now represent anything tangible, as they once did’. Please explain that.

The significance of full-reserve banking, or 100 Percent Money should be obvious. With such a system, again as in the Kucinich Bill, banks could only lend real money that was created by the government’s money administration.

This removes the moral hazard associated with fractional lending, including the necessity for a public backstop in the FDIC.

It removes the basic financial instability caused by monetary expansions and contractions that are fractionally multiplied and then divided – the same one that Minsky observes is inherent in the system, his flaw being in believing that the inherence is in the actions of the players in the bubbles and busts, as opposed to the architecture of the system of fractional lending.

The significance of full-reserve banking is well explained in the 1939 Program for Monetary Reform, authored by Fisher, Knight, Douglas and several other prominent progressive economists.

http://www.economicstability.org/history/a-program-for-monetary-reform-the-1939-document

This and other progressive offerings for reform provide the monetary economic foundation for the Kucinich Bill.

Some MMTers would have us believe that the fact the banks first lend and then acquire reserves (endogenous money) lends the reserve factor to zero significance in terms of monetary policy and especially the monetary system.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

All it does is remove the smokescreen from a hint of structural stability in the banking and lending system.

Our quarrel with fractional-reserve banking is that it allows a small group of private individuals to create their own purchasing power in a modern economy, leaving the Restovus to borrow that purchasing power from those privileged to reside on the other side of the window.

There is no valid reason to maintain the fractional reserve system, and to preserve that private privilege of wealth creation for the money masters.

Thanks.

To Neil Wilson

There is limited truth to your description of reserve significance and the balance of banking and monetary operations.

First with regard to the OMG 19th century bogeyman.

In reality, a transition to full-reserve banking would move us forward FROM this hundred-year experiment with fractional-reserve lending, by necessity and definition.

It would NOT take us back to the 19th, but forward to the 21st Century monetary structure.

YOUR Bank of England Governor Mervyn King recommended its consideration at the last Buttonwood Gathering. So, to look at it as a move backward is, quite literally, in the eye of the beholder.

As to the significance of the discount window with full-reserve banking: OUR previous discussion took us through the point that full-reserve banking ENDS the discount window function of banks acquiring necessary reserves to satisfy regulatory requirements. So what?

As to the ‘greater’ significance of central bank lending to banks to meet legitimate lending needs, where capital accumulation is either otherwise too costly or burdensome, that provision is completely covered and available in the Kucinich Bill.

So, to say that full-reserve banking is either a throwback (to when) or only significant if the discount window is closed is to say nothing. The reserve-purchasing discount window function is unnecessary and therefore does not exist, and the bank-lending window exists FULLY within the nationalized public central bank.

The wordy missive about credit stock and turnover is meaningless to this discussion of reserves.

Of course, your correct explanation is that -regardless of the source – money being adequate provides the bankers with exactly the same amount of potential spread and profit.

The difference, which should be obvious to all MMTers trying to figure out why the global economy is stuck in “unemployed”, is that NOW the government doesn’t have the power to create the money needed, and the private banks have the power but refuse to use it.

As it says in Finding # 10 of H.R. 2990 –

(10) Congress is stymied by competing forces: a desire to put people to work and an

aversion to borrowing money to create programs to do so.

Ain’t we all?

joebhed,

The theory of Loanable Funds is false, therefore:

Banks do not have the power to create money without first having credit worthy borrowers.

Governments already have the power to create money but refuse by pretending that they do not have the power to do so when it suits the agenda.

It might benefit the discussion to know the problems that the “full reserve” proposal intends to solve and the mechanism through which the proposal acts to resolve these problems.

joebhed,

Your reply at 7:42 had not appeared when I posted my previous response.

Reserves originally referred to physical gold that had tangible value outside the banking system. This is no longer the case. Neither the electronic entries in your bank’s name at the Fed, nor the ones in your name at your bank are worth anything tangible outside the banking system. What is the significance of the ratio of one worthless thing to another? It’s just a convention held over from when it did mean something.

You said: “Our quarrel with fractional-reserve banking is that it allows a small group of private individuals to create their own purchasing power in a modern economy, leaving the Restovus to borrow that purchasing power from those privileged to reside on the other side of the window.”

I don’t understand this. By what mechanism does this occur? How is this purchasing power created? I’m not disagreeing that it occurs, but I think it is better to understand the mechanisms of problems before proposing solutions.

I think advocates of “full reserve” proposals vastly overestimate the “vig” for the banks that is baked in the cake and underestimate the money extracted by outright fraud and other behaviours that could be easily regulated without touching the fundamental system.

The other mistake I see often made is that some how “fractional reserves” and interest are inseparable from the infinite growth paradigm. This mistake is simple confusion of real and nominal quantities.

Jeff65, not sure if this will answer your question but …

If there is a 10% reserve requirement and it is enforced (meaning allowing the fed funds rate to rise), then that could stop debt being produced.

If there is a 0% reserve requirement, more and more debt won’t increase the fed funds rate.

Jeff65, I’d rather see this question:

If an economy needs more medium of exchange, how should that happen? And, should it be “currency” with no bond/loan attached or debt?

I’m of the opinion that an economy should have all “currency” and no private debt and no gov’t debt because of the time differences between spending and assumed earning that debt allows.

“YOUR Bank of England Governor Mervyn King recommended its consideration at the last Buttonwood Gathering.”

He also recommended Quantitative Easing in a design that doesn’t return the Gilt Interest surplus to HM Treasury on a regular basis meaning that HM Treasury quickly reverses the Bank Reserve expansion and puts Gilt yields back up.

An appeal to authority of that nature is not just the normal logical fallacy.

The problem with the fractional reserve argument is that they bang on about a moral argument that isn’t actually true.

Fundamentally the banks have a licence to maintain a dematerialised credit stock that is issued by the state often for a fee (in the UK banks with a licence have to maintain an amount of capital at the Bank of England in the form of a credit deposit ratio (CDR) which pays no interest. That CDR is related to the amount of loans in issue). That licence is then insured by the state.

It is simply an outsourcing operation to a private bank. There is no economic difference between a $500mn licence to maintain a dematerialised credit stock or $500mn in their central bank reserve account at 0% interest on a 100% reserve.

The real vice in banking (if there is any) is in maturity transformation and obfuscation of what they call ‘capital’.

To Jeff65 at 10:37

1.Why do you bring up loanable funds theory – as it primarily deals with interest rates related to supply and demand for loanable funds?

2. If banks have no authority to make loans except when there is a real ‘creditworthy-borrower’ need for the money in the economy, then the financial crisis proves obviously that the term ‘creditworthy-borrower’ is as subjective as all get out. But, what’s the point, anyway?

3. If by “pretending that they(government) do not have the power” to create money, you are including legally-binding public policy constraints on the government body, then I think it is you pretending as to what pretending means.

4. I have already pointed to an explanation of the benefits of full-reserve banking in the Fisher-Knight-Douglas 1939 Program, also contained in many economic textbooks in Fisher’s writings, notably in Chapter Ten – Reserve Requirements of Ritter’s Money and Economic Activity – The Instruments of Central Banking(Houghton-Mifflin, 1967).

This problem of debt-money based fractionally-reserved banking is related in this quote by economist and FRB-Atlanta Credit Officer Robert Hemphill :

“” This is a staggering thought. We are completely dependent on the commercial Banks. Someone has to borrow every dollar we have in circulation, cash or credit. If the Banks create ample synthetic money we are prosperous; if not, we starve. We are absolutely without a permanent money system. When one gets a complete grasp of the picture, the tragic absurdity of our hopeless position is almost incredible, but there it is. It is the most important subject intelligent persons can investigate and reflect upon.””

I have already mentioned it many times. We are without a permanent money system. We have no means to have any means of exchange unless the banks issue more debts. If you don’t see any problem with that “tragic absurdity of our hopeless situation”, then, again, unemployment are us.

Thanks.

to Jeff65 at 11:56

There is absolutely no connection between the concepts contained in fractional-RESERVE and full-RESERVE banking, and the central bank/Treasury holding of gold reserves against currency issuance.

Gold was NEVER the required holding of a bank against loans.

Gold reserves were strictly a central bank management tool to protect currency values when these were tied to the commodity – it had nothing to do with reserves against lending. This is either a red-herring or a rabbit hole construct – WHY do you bring it up?

You act as if it is I who believe that the reserves backing my bank account are related to gold holdings. Please stop with these constructs as if they were my mis-understanding.

What I don’t understand is why you take the time to “correct” me from NOTHING that I believe in or have stated.

It is obvious that you do NOT understand full-reserve banking at all.

It is only under full-reserve banking that a real-dollar of reserve holdings allows or permits that a bank can lend that real-dollar out.

That is its limitation and its protection against both booms and busts and bank runs.

If you want to say that we should abandon any reserve for bank loans, then say so, and eliminate fractional-reserve banking completely.

But, where does that leave you?

The little missive about gold-reserves sounds like you want to have to have gold reserves for banking.

As to the power to create purchasing power being some kind of a mystery…. Please observe a single loan transaction, multiplied by millions.

The bank has NOTHING, except the power to create purchasing power as bank credit and to lend that purchasing power to the borrower at interest, again with a PN for the P+I payments and collateral security.

The bank creates purchasing power for the borrower and itself.

The PN includes the P+I.

The I is the banks own purchasing power.

No other business has the power to create its own profit-making assets except banks.

Why is there any mystery to this statement?

More importantly, as those bank-credits temporarily(until repaid) serve as the nation’s money supply as an interest-bearing debt, the failure to EVER create the money needed for interest payments DOES feed the infinite growth paradigm.

I suggest a listening to the work of Dr. Bernd Senf, Pr.em. at the Berlin School and a leader of the European “Monetative” movement, for a complete explanation of the perils of compounding interest in a debt-based money system.

http://blip.tv/file/4111596

As to the banks’ vig on lending I never said THAT was inappropriate. It is rather their somewhat inadvertent control of the nation’s circulating medium that puts them at fault.

With full-reserve banking, the banks would have exactly the same vig. The only difference would be that we the people would never need their lending to have a money supply.

Thus correcting for Robert Hemphill’s staggering thought.

Thanks.

To Neil Wilson

Moving on, I guess.

I cannot imagine how the mixing various policy measures at HMs Treasury and CB have any bearing to this discussion.

You claim that opposition to fractional-reserves is a bang-on about a moral argument that is not true.

Please understand, Neil, that opposition to fractional-reserve banking is a well thought out social- and political-economic bang-on, with a moral argument thrown in as sauce for the pudding.

If you read the 1939 Program or Chapter Ten on Reserve Requirements in Ritter’s Money and Economic Activity – The Instruments of Central Banking(Houghton-Mifflin,1967) reference provided to Jeff65 above, it is all about economics and saving capitalism from itself – something that MMT deigns to accomplish as well.

The authors’ intent in the 1939 Program is to suggest a legal requirement remedy “to end the lawless variability in the supply of the nation’s circulating medium”. That is an economic construct, Neil, and not a moral argument.

That is an economic construct that solves for the problem identified by Atlanta Fed Credit Officer Robert Hemphill. To solve the very real problem that we are without circulating medium TODAY, should satisfy the Restofus.

Your description of the banking service provided is somewhat misleading , even if parochial to the UK. To maintain a supply of capital on deposit at the CB is hardly to pay a fee. They can take it out and turn in their license at will, and in return for the license and deposit, the GUV insures the depositors – a totally unnecessary act of promoting moral hazard that would be eliminated with full-reserve banking.

What IS different between the two systems is not limited to the full-versus-fractional reserve argument.

I would characterize it thus.

On the one hand, the bankers create $500 million out of nothing, collecting interest from every borrower including the federal Treasury, who itself has the power to create the money, but who must collect its interest obligation from every taxpayer. Upon repayment the debt and the money are cancelled, requiring an additional $500 million in loans to prevent deflation.

On the other hand, the federal Treasury creates the $500 Million WITHOUT DEBT and pays it into existence to pay for government services, eliminating both government debt and taxpayer interest payments. That same $500 million remains in the national economy in perpetuity, or until it is removed by the government through taxation in order to meet required monetary policy goals on maintaining the stability of its buying power.

This posture that private wealth-creation via debt-issuance is “simply an outsourcing to a private bank’ is sounding quite Hamiltonian, cum Rothschildian, from where I sit.

“Permit to issue and control the nation’s money and I care not who makes its laws” comes to mind.

For a look at the long-term consequences of debt-free-at-issuance public money compared to maintaining fractionally-reserved, debt-based money issuance, please see the work of Japanese economist Dr. Kaoru Yamaguchi of Doshisha University here:

http://www.old.monetary.org/yamaguchipaper.pdf

Full-reserve banking without deposit insurance places the burden of maturity transformation where it belongs – in the lending policies of the bankers.

Thanks.

“you are including legally-binding public policy constraints on the government body, ”

And why is it easier to change the ‘legally-binding constraints’ on private banks than the ‘legally binding constraints’ on the entity that makes the ‘legally bind constraints’?

“”to end the lawless variability in the supply of the nation’s circulating medium”.”

That’s a moral argument. The variability is due to demand and where you provide storage facilities in a bank it will not change that. Money becomes inert when stored. It doesn’t matter if that is stored dematerialised or in specie. It is out of circulation.

So you will still get the circulation issues caused by banks inability to predict the future accurately.

And in both fractional and full reserve systems you will still need government fiscal spending to offset that mismatch between borrowing and saving.

“On the other hand, the federal Treasury creates the $500 Million WITHOUT DEBT and pays it into existence to pay for government services”

And there we have the nub of it. It’s a cleverly disguised request for more government spending and debt cancellation – since that’s the only way to get from where we are to this so called nirvana.

Well we’re all for that – but you’re then comparing apples and oranges. What does a fractional banking system behave like when you inject $500 million of new government cash into the system via spending?

“That same $500 million remains in the national economy in perpetuity, ”

But not necessarily in circulation – for example when it is hoarded in storage in a bank vault.

Again the arguments presented are the wrong ones. It’s all bile and bluster about the so called vices of the private banks and yet when you glance at the idea for a second or two there is no fundamental difference between the two systems in their economic effect. The claims made for it are the result of other features:

– we need more government spending to prevent private debt build up – correct.

– it won’t affect the nature of lending one bit – except that banks will go bust more often due to liquidity squeezes.

– structurally the response outputs appear the same.

Now I can see an argument that full reserve is easier to regulate, and I can see an argument for matched funding. But the rest, as presented here, frankly falls into religious territory.

To Neil Wilson ( missed this a few days ago)

To challenge my monetary economic ideas, based as they are in traditional progressive political-economic writings, as consisting of ‘moral arguments’, ‘religious territory’, ‘bile and bluster’ without a hint of why this is so, is resort to verbal blather.

On the rest of your posting, Neil.

You claim, vacuously, that ‘ending the lawless variability of the circulating medium’ is a moral argument. Where there is legality, politics and economic science closely intertwined, you see morality. Seems like suffering from tunnel-vision here.

The document from which the quote came (The 1939 Program for Monetary Reform) was written by six of the most prominent economists of the time, including political scientists and economists, and publicly endorsed by over 400 economists as well.

When was the last time THAT happened.

Please explain why putting the basic lynchpin of monetary management into a legal construct rather than rely upon market-makers is connected in any way to morality.

In the 1939 Program, note was made that upon abandoning the gold-standard several Scandinavian countries had adopted means and methods by which the driving parameter of monetary policy would be to stabilize the buying power of the currency.

The authors of the 1939 Program were recommending adoption of such a monetary mandate through statute. The following are the points made in the 1939 Program in support of such action, which again included a needed transition to full-reserve banking.

The Standard of Stable Buying Power

(2) Several of the leading nations now seek to keep their monetary units reasonably stable in internal value or buying power and to make their money supply fit the requirements of production and commerce.

(4) Our own monetary policy should be directed toward avoiding inflation as well as deflation, and in attaining and maintaining as nearly as possible full production and employment.

The Criteria of Our Monetary Policy

(5) We should set up certain definite criteria according to which our monetary policy should be carried out.

(6) The criteria for monetary management adopted should be so clearly defined and safeguarded by law as to eliminate the need of permitting any wide discretion to our Monetary Authority.

I see NO morality made in the sound political-economic argument for ending the “lawless variability in the supply of the nation’s circulating medium”.

Your ‘morality’ argument probably results from your lack of understanding of full-reserve banking evident in your commentary re “vaulting”, “storage facilities” and “hoarding”.

I presume you have read my two documents here – The Kucinich Bill H.R. 2990 and the 1939 Program. If not, please do and leave an intelligent comment with reference to what is contained therein.

Moving on.

Sorry, the money-variability is not just due to “demand”. Bankers have $Trillions in reserves, they are not lending. You should do some reading on the pro-cyclicality of the fractional-reserve system. Regardless of the ‘endogenous money’ argument, the control of the nation’s money supply by private, self-serving individuals and corporations is why the problems of contraction, hoarding and betting against the Restovus needs to be changed.

It is the right-wing argument in favor of maintaining the private money status quo that prevents us from doing anything about the present state of the economy. Do you think that if we had a public money system we would all be moving in the direction of austerity-driven poverty so that the bankers can pay off their counter-party debts?

Why should we EVER rely upon anyone other than our national ‘selves’ to have an adequate supply of circulating media?

On the matter of ‘circulation’. Government spends the money into existence, debt-free. This is consistent to a TEE with MMT, Chartalism and Lerner’s ‘functional-finance’ concepts of monetary economics.

As such, the money begins its life in what we now call the M-1 part of the money supply, not in the bankers’ reserve accounts. It is in circulation. It gets spent. It gets deposited in savings/investment accounts for which it receives interest.

When the banks know there will be adequate money government-issued to support the potential for economic growth, and they are paying interest on any money they CAN use to make money, what is their incentive to hoard or store money?

The money administration now has the power to overcome any monetary hoarding – velocity being one of the factors determining monetary issuance amounts..

Your arguments here are specious, in every sense of the word.

I wrote: “On the other hand, the federal Treasury creates the $500 Million WITHOUT DEBT and pays it into existence to pay for government services”

You reply: “And there we have the nub of it. It’s a cleverly disguised request for more government spending and debt cancellation – since that’s the only way to get from where we are to this so called nirvana.”

Uuummmm….., a cleverly disguised request? Nirvana?

I thought that part was Lerner 101.

The “more government spending” is what is called the national budgeting process that happens every day of every year. There is no ‘increase’ in the spending as a result of this. The debt-cancellation is again correct, as the money is not borrowed. So ?

But again, that has always been my understanding of what Lerner’s “functional finance’ was proposing. It was the major differentiation with Keynes. So, if you support MMT, how can you be against Lerner’s debt-free money principle?

I wrote: “That same $500 million remains in the national economy in perpetuity, ”

You wrote: “But not necessarily in circulation – for example when it is hoarded in storage in a bank vault.”

Sorry, Neil, hoarding of money is passé with both government-issuance and full-reserve banking. I have already explained why. The government can balance its issuance with hoarding(lack of monetary velocity) and the incentive to hoard(increase scarcity and interest costs) is gone as well, and savings depositors receive interest, so the banks MUST lend in order to remain viable. But, if they’re honest bankers, why wouldn’t they?

Your entire notion that there would be no difference in both the availability of credit and stability of the money system with either Fractional or Full-Reserve Banking is laid bare by the two sections of the 1939 Program headed by those titles that I linked to above.

I invite any reader to please make your own determination. Feel free to contact me directly at our website at http://www.economicstability.org.

Thanks.

“There is no ‘increase’ in the spending as a result of this. ”

There most certainly is, otherwise you can’t get from a 10% reserve system to a 100% reserve system.

And then by definition is the banks are operating at 100% rather than 10% the state must spend into existence the other 90% to allow the same level of economic activity.

If you want to change the credit money into fiat money, then you have to supply more fiat money to offset the loss of credit money. Therefore more government spending or much lower taxes to supply the required savings.

“and savings depositors receive interest, so the banks MUST lend in order to remain viable.”

Given that the system saves more than it lends over time, and there is no leverage, savers will eventually be competing for somewhere to store their money. Therefore it is likely that savers will have to pay to store their money in a bank due to competition.

“So, if you support MMT, how can you be against Lerner’s debt-free money principle?”

It’s not debt free – loans still attract interest and the banks will extract exactly the same margin from the money as they do now. There is no magic in 100% reserve banking. It is exactly the same as a fractional system, just with more 000s on the reserve accounts. In specie rather than insured.

Hence why MMT economists are agnostic about fractional or 100% reserve banking.

So but the arguments put forward are only ever that it is *terrible* that *private* banks can create money. I’m completely agnostic about it but tend toward the same view Bill has expressed here on the blog – that tighter regulation of the fractional system is probably more appropriate.

The standard counter-cyclical spending policies, such as the Job Guarantee, can dampen the credit cycle.

Neil

As I said. Your comments exhibit a complete lack of understanding of the full reserve system. I am answering here, but I will soon post a video response, and a link to it in this thread.

By now, it is very possible that we are the only ones aware of this dialogue.

I earlier, and again now, ask whether you had read both the Kucinich(K-) Bill and the 1939 Program. I hope so, but please just say what YOUR source is for how achieving full-reserve banking would play out.

For instance, when you say: “There CERTAINLY is…” an increase in government spending(the federal budget) as a result of implementing the full complement of policy measures(*) that accompany full-reserve banking.

(*) In other words, the policies necessary in recognizing that full-reserve banking CANNOT be achieved without replacing the credit-creation of ‘things that serve as, and count as, money’.

You say – “”, otherwise you can’t get from a 10% reserve system to a 100% reserve system.””

Then you lay out a scenario involving the government “adding” the reserves to the system, rather than replacing the un-reserved fraction of mostly demand deposits, but also whatever other forms of bank assets that serve as reserves against bank lending. This is YOUR construct. It is just plain silly, Neil. Government does not need to ADD to the money supply in order to achieve full-reserves.

Your construct for achieving full-reserves denies the content of everything written about full reserve banking. So, where did you get it?