I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

One quarter shorter, three quarters deeper

Yesterday, October 5, 2011, the UK Office of National Statistics released their Quarterly National Accounts, June 2011 for the second quarter. The data revealed an economy that barely grew at all in the period from April to June. It also showed that households are continuing to reduce their overall consumption. The data also revised earlier releases and we now learn that the UK recession was deeper (for three quarters) than previously thought but was one quarter shorter. The data release continues to demonstrate that the policy settings (which are pushing towards contraction) are completely wrong for the spending trends that are being revealed in the private and external sectors. If the British economy goes back into recession there will be only one cause – the wilfully irresponsible management of fiscal policy.

One of the articles that took my notice a few weeks ago was this Bloomberg Editorial (September 19, 2011) – Republicans Vow Revolution, Blame Obama for ‘Uncertainty’: View – which recounted how the Republicans in the US had distilled all explanations for the crisis and its retarded recovery on one word – “uncertainty”.

The Bloomberg editorial opens:

How exactly, according to Republicans, is President Barack Obama supposed to have caused the current economic malaise and high unemployment?

You can criticize Obama for running up huge deficits that may wreck the economy in the long run, but in the here and now, even a feckless deficit-spending program can only stimulate the economy and create jobs. However dismal the unemployment rate is now, it would have been worse without the hundreds of billions pumped into the economy by two administrations and the Federal Reserve.

The positive contribution of the US fiscal stimulus (with supporting monetary policy) cannot be overstated even though many notable mainstream economists (such as Robert Barro, John B. Taylor) claim it made the recession worse. The same applies for every nation – even those in the EMU. Without the two-pronged attack – first of shoring up the financial system to ensure the banks could lend and second, the substantial increase in government net spending (which was both the product of discretionary fical decisions and the automatic stabilisers) – the world economy would have collapsed into Depression.

That is not to say that the fiscal interventions were sound and well designed. I generally think they were unsound in the sense that they did not support job creation as much as they should have.

The Bloomberg editorial then closed in on the “Republican theory” which could also be generally labelled the current neo-liberal consensus:

The Republicans have a theory. With remarkable unanimity, Republican leaders in Congress and the party’s presidential candidates have parroted a one-word explanation: “uncertainty.”

So imagine a new government being elected on the promise of cutting national debt and in its first budget outlines a very clear plan to seriously cut the national budget deficit, reduce taxes (but definitely not put them up), cut public employment and free up the regulative environment. Such a government also pronounced its “pro-business” credentials (self-styled).

In that situation, if the “Republican view” was correct we would expect to observe within a few months (certainly within a year) of the new government a reduction in private uncertainty which if the concept has any operational application should influence discretionary behaviour such as spending and employment.

It would be reasonable to expect business confidence to rise which should mean that private investment would accelerate as they anticipate a consumer revival.

It would be reasonable to expect firms to be keen to get staff in place to meet the renewed expectations of increased orders.

It would be reasonable to expect consumers to become more confident and this confidence to translate into their consumption expenditure.

The reality is that the emerging available data (from several disparate sources) rejects each of these propositions. The reality is the exact opposite to what the neo-liberals predicted.

Second-quarter National Accounts

Yesterday, October 5, 2011, the UK Office of National Statistics released their Quarterly National Accounts, June 2011 for the second quarter.

The data showed that real GDP growth for the quarter was 0.1 per cent, slowing from 0.4 per cent in the first quarter 2011. It also showed that the slowdown in consumer spending is accelerating. Consumer spending fell by 0.8 per cent in the June quarter after declining by 0.6 per cent in the March quarter.

It is the fourth consecutive quarter than consumption spending has declined.

There was a pick-up in private investment in the June quarter but this has been very volatile over the last year and probably connected to the export growth that has now disappeared. The data showed that the production sector declined overall.

Net exports deteriorated because the decline in exports was larger than the decline in imports.

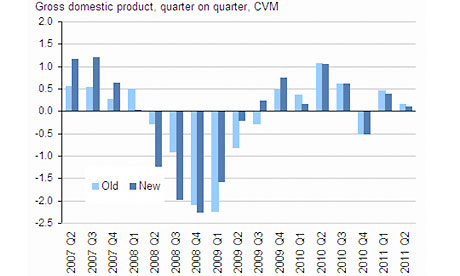

The data release also revised earlier estimates. The following graph shows the impact of the ONS revisions. It turns out that the recession was one quarter less but much deeper than previous data releases revealed.

The data shows that the British economy was turning again before any of the current Euro turmoil manifested which puts paid to the claims by the Government that the strife across the Channel is causing the current uncertainty in Britain.

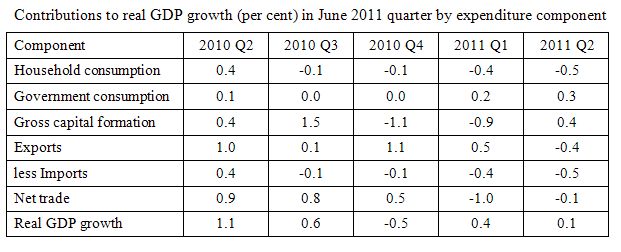

The following Table shows the contributions to real GDP growth in the June quarter by expenditure component (they do not add up to the real GDP growth shown because I have not included all the components). The data is available HERE.

Household consumption subtracted a ½ of one percent from the overall real growth – which is a very deflationary result.

It is interesting that the fiscal austerity has not yet hit General Government consumption (although government investment spending has fallen sharply – not shown).

The data also suggests that an export-led recovery will not occur with net exports undermining growth.

Commenting on the performance of the economy in 2011, the ONS says that the “weakness of growth in both quarters, particularly the second quarter, reflects a number of pressures that are being felt in the wider economy by both business and households”:

– continuing declines in real wage growth, which resulted in declines in consumer demand and consumer confidence;

– an uncertain labour market, which can feed through to weaker consumer confidence and consumption;

– relatively high rates of inflation and in particular high and rising commodity prices, though this is offset to some extent by relatively low growth of labour costs;

– a weakening global economic position, in particular the UK’s key export markets of the euro area, wider Europe and the US;

– volatility and weakness in financial markets;

– low returns on saving.

Clearly they cannot implicate the fiscal strategy as a driving factor in this weakness. With the household consumption sector declining fast and export markets shrinking (particularly as the Eurozone melts down), it is hard to see how business investment will continue to grow.

All this data should be telling the British government that they have their policy settings wrong – far to tight. But then it is clear that the Prime Minister, himself, doesn’t understand economics very well.

The UK Guardian (October 5, 2011) article – Cameron rewrites conference speech to remove credit card pay-off call – reports that the PM:

… has hastily rewritten his conference speech to remove any suggestion that he is either urging or instructing the public to pay off their credit card bills – a move that could dampen consumer demand and worsen the recession.

The article shows that an earlier (“pre-briefed”) version of the speech that the PM presented to the Conservative conference had read “The only way out of a debt crisis is to deal with your debts. That means households – all of us – paying off the credit card and store card bills.”

The revised version then read “That is why households are paying down the credit card and store card bills.”

The article quotes the “deputy Conservative chairman” as saying that Cameron was actually meaning:

As households have paid off the debt, so the government has got to do the same.

It is clear that households are now saving heavily and the consumption spending data is consistent with that.

Regular Guardian economics writer Larry Elliot (October 5, 2011) in his article – Paying off your debts hits the economy, stupid – concluded that:

David Cameron had second thoughts overnight about his “pay off your debts” speech to the Tory party conference, and little wonder. Not since Sir Alec Douglas-Home was skewered by Harold Wilson after admitting he used matchsticks to help him with economics has a prime minister looked so weak in his understanding of the science.

He notes that if the private domestic sector pays off the very high level of “consumer debts too rapidly” then it “would plunge an already enfeebled economy back into deep recession”.

While that conclusion is true in a static sense, the reality is that the private sector has to reduce its overall debt exposure. But I would actually agree with the PM that households should be doing what they can to get rid of their debt burdens (or bring them down to manageable proportions).

But where the conservative message fails is in the response that government should make in this context. With net exports not adding to growth, it becomes an impossibility that growth can occur if both the private and public sectors spend less than their income.

That conclusion – which is an accounting statement drawn from an appreciation of the way the Nationala Accounts work – is clearly not understood by the Government (nor the British Opposition) nor most of the financial/economic commentators.

There are three sources of growth if household consumption is negative: private investment, government spending and/or net exports. Fiscal austerity will undermine the government’s contribution over the next 12 months and net exports are already negative and will probably deteriorate further. That leaves private investment which is interlinked with export and consumption behaviour. Now both are in decline, private investment will probably follow.

The June quarter 2011 National Accounts outcomes also demonstrate that the Budget forecasts will be impossible to achieve in the current year. There is no way it will achieve the reduction in budget deficit that it proposed in the 2011-12 budget which also means that public borrowing will be higher (given the institutional arrangements that Government uses which unnecessarily tie deficits to borrowing).

The 2011-12 Budget forecast that real growth would be 1.7 per cent in 2011 growing to 2.5 per cent in 2012. At the time, I said these were ridiculously optimistic given the trends in private spending that were apparent then.

Now it is clear that the British economy will not meet the 2011 forecast and I also suggest the economy will not get near the 2012 forecast. Taken together that means the automatic stabilisers (slower tax revenue and increased welfare support) will work to undermine the Government’s predictions.

This demonstrates why trying to force some specific fiscal outcome independent of what is going on elsewhere in the economy is counter-productive and poor economics.

Other indicators of sentiment

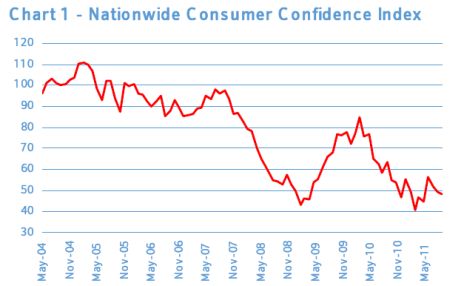

One measure of consumer confidence in the UK is provided by the Nationwide Building Society Consumer Confidence Index – which showed that sentiment fell modestly (from a very low base) in August 2011. The overall assessment was that:

the UK is unusually reliant on exports to drive the economy forward at present. Household spending is under severe pressure, with wages not rising fast enough to keep up with the cost of living, while government spending is being held back by austerity measures. Therefore, until exports pick up, labour market conditions are likely to remain difficult, and without a stronger labour market, confidence is likely to remain subdued.

And then they noted that “the US recovery may be running out of steam and ongoing problems in the Eurozone” will make it much harder to maintain any export growth.

The following two graphs are taken from Nationwide’s August Publication and are self-explanatory.

Other indicators of consumer confidence are telling a similar story. The UK consumer sentiment survey conducted by GfK NOP Ltd shows that the index is “ten points lower than this time last year”.

Related information comes from the Markit/CIPS UK Services PMI which was published yesterday (October 5, 2011).

The Chief Economist at Markit said of the results:

A surprise uplift in growth is welcome news, coming on the back of a similar upturn in manufacturing, but masks the fact that all is not well in the UK services economy.

… many firms also reported that the ongoing expansion was only achieved by eating further into backlogs of work. This is clearly not sustainable and growth of new business will need to pick up in the coming months to prevent a downturn in both business activity and employment in the final quarter of 2011. Companies are already reluctant to take on extra staff, with employment more or less stagnating in September, as worries about the economic outlook at home and abroad intensified. Business confidence about the year ahead slipped to its lowest since March 2009 and is running at a level only ever seen before in periods of crisis.

The following graph shows the September 2011 measure of business confidence referred to in the last quote.

The common theme you will see in all these performance or sentiment graphs is that the UK economy plunged into a very deep recession and all the private indicators that might tell one something about “uncertainty” dropped markedly.

The national government then introduced a fiscal stimulus and stabilised the financial system. As noted above, we can criticise the design of the stimulus and clearly conclude it wasn’t sufficient given the collapse in the private spending but the economy did resume growth eventually and the private “sentiment” indicators all headed in a positive direction.

Then a national election is held (May 2010) and the tough talking conservatives take power and make all the proper “neo-liberal” noises and follow them up with action – the period of fiscal austerity then is slowly implemented. All the private indicators then start plunging again.

The pattern is exactly the opposite of what the neo-liberal (fiscal austerians) predicted yet totally understandable and consistent with Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) conjecture.

It is a demand-side problem

I also note in recent weeks a growing denial that there is a demand problem in the UK (and elsewhere). Some comments on this blog reflect that growing trend among conservatives to blame the supply-side, principally a lack of productive opportunities

In this blog (for example) – Britain – wrong problem, wrong solution – I noted that the “problem facing the UK economy is a lack of demand”.

There is a view I have picked up on that says something like the private credit-binge which drove growth in the years leading up to the crisis created an illusion of real growth.

The conclusion then is that the UK economy (and all other economies presumably) has less productive capacity available than would be indicated by the unemployment and underemployment queues. The latter clearly suggest there are productive resources lying idle.

The argument then suggests that the government sector can do little to spur renewed growth. Further, economies will have to tolerate near zero growth (and entrenched unemployment) for “the foreseeable future” and any attempts by government to change that will just make the situation worse – presumably reduce the growth rate even further.

If you believe that then your understanding of macroeconomics is very limited indeed.

I have a reasonable understanding of life in Britain (having lived there and also travelling there reasonably often over the last two decades or more). I have observed major shortfalls in public infrastructure and a decaying housing stock. I have observed regional disparities in personal care services and public education.

It is true that a prolonged recession will eventually start to impact on the potential growth path (reducing it) as capacity is lost and not replaced. I wrote a PhD thesis on matters relating to that.

In that research, I showed that the increasing NAIRU estimates (based on econometric models) merely reflected the decade or more of high actual unemployment rates and restrictive fiscal and monetary policies, and hence, were not indicative of increasing structural impediments in the labour market? I also showed that there was no credibility in the claims that major increases in unemployment are due to the structural changes like demographic changes or welfare payment distortions.

For the technically minded you might like to read the original article which appeared in Australian Economic Papers, December 1987 which has the formal theoretical model and econometric analysis.

This work was part of a new research agenda that was able to show that structural changes were in fact cyclical in nature – this was called the hysteresis

effect. Accordingly, a prolonged recession may create conditions in the labour market which mimic structural imbalance but which can be redressed through aggregate policy without fuelling inflation.

The facts are as follows. Recessions cause unemployment to rise and due to their prolonged nature the short-term joblessness becomes entrenched long-term unemployment. The unemployment rate behaves asymmetrically with respect to the business cycle which means that it jumps up quickly but takes a long time to fall again. But this behaviour has to be seen in the context of the policy position that the national government takes at the time of the recession and the early recovery period.

It is true that once unemployment reaches high levels it takes a long time to eat into it again because labour force growth is on-going and labour productivity picks up in the recovery phase. You need to run GDP growth very strongly at first to absorb the pool of idle labour created during the recession unless you provide a strong public employment capacity that is accessible to the most disadvantaged (for example, this is what the Job Guarantee is about!).

It is also the case that if GDP growth remains deficient then the idle labour queue will remain long and employers will use all sorts of screening devices to shuffle the workers in the queue. They increase hiring standards and engage in petty prejudice. A common screen is called statistical discrimination whereby the firms will conclude, for example, that because on average a particular demographic cohort is unreliable, every person from that group must therefore be unreliable. So gender, age, race and other forms of discrimination are used to shuffle the disadvantaged from the top of the queue.

The long-term unemployed are also considered to be skill-deficient and firms are reluctant to offer training because they have so many workers to choose from.

But to understand what happens during a recession we need to consider the cyclical labour market adjustments that occur.

The hysteresis effect describes the interaction between the actual and equilibrium unemployment rates. The significance of hysteresis is that the unemployment rate associated with stable prices, at any point in time should not be conceived of as a rigid non-inflationary constraint on expansionary macro policy. The equilibrium rate itself can be reduced by policies, which reduce the actual unemployment rate.

The idea is that structural imbalance increases in a recession due to the cyclical labour market adjustments commonly observed in downturns, and decreases at higher levels of demand as the adjustments are reserved. Structural imbalance refers to the inability of the actual unemployed to present themselves as an effective excess supply.

The non-wage labour market adjustment that accompany a low-pressure economy, which could lead to hysteresis, are well documented. Training opportunities are provided with entry-level jobs and so the (average) skill of the labour force declines as vacancies fall. New entrants are denied relevant skills (and socialisation associated with stable work patterns) and redundant workers face skill obsolescence. Both groups need jobs in order to update and/or acquire relevant skills. Skill (experience) upgrading also occurs through mobility, which is restricted during a downturn.

An extensive literature links the concept of structural imbalance to wage and price inflation. It can be shown that a non-inflationary unemployment rate can be defined which is sensitive to the cycle. Given that inflation typically results from incompatible distributional claims on available income by firms and workers, unemployment can temporarily balance the conflicting demands of labour and capital by disciplining the aspirations of labour so that they are compatible with the profitability requirements of capital. This is the underlying reason why inflation targetting uses unemployment and a policy tool rather than as a policy target!

Why is all that important? Answer: because the long-run is never independent of the state of aggregate demand in the short-run. There is no invariant long-run state that is purely supply determined.

So these NAIRU-mindsets that just assume that an unemployment rate that touches the “made up” Treasury NAIRU line represents full employment do not provide a reliable guide to policy.

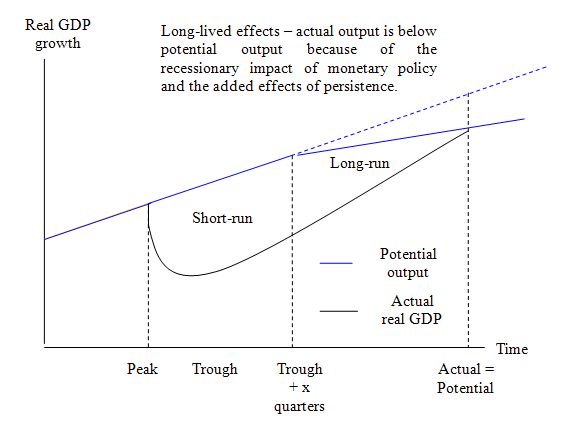

In the blog – The Great Moderation myth I presented the following diagrams which also bear on the point.

Hysteresis theories purport permanent losses of trend output as a consequence of the disinflation. The following diagram shows that the real GDP losses are much greater than you would estimate if you used the neo-classical long-run constraints imposed by the OECD.

You can see that potential output falls after some time (as investment tails off) and actual output deviates from its potential path for much longer. So the estimated costs of the disinflation (and fiscal austerity supporting it) are much larger than the mainstream will ever admit.

But the point of the diagram is that the supply-side of the economy (potential) is influenced by the demand path taken. Hysteresis means that where you are today is a function of where you were yesterday and the day before that.

By imposing these artificial conservative constraints on their simulations, the OECD is guaranteeing that the main neo-liberal results hold in the long-run.

There is no informational content at all in their outcomes.

I don’t want to get into sidetracks like whether growth is desirable. I appreciate all the arguments that tell us we have to dramatically change the composition of growth away from carbon-intensive outputs and other environmentally-damaging ends. I do not think a market system left alone can achieve that and so there is a prima facie case for more regulation and public activity. That is the topic for another blog though.

Taken those concerns as given, I could generate millions of jobs in Britain in a relatively short period of time. They would be involved in community development, personal care services, environmental care services and would be tailored to absorb relatively unskilled workers.

The capital requirements for these jobs would be relatively modest which means that not much investment would be required to ensure the jobs could be functional.

The problem is not a lack of capacity. There are millions unemployed. The problem is a lack of demand for their services. That demand should be provided at present by the Government which would help revive the private sector – reduce its uncertainty and inspire renewed confidence.

There is nothing I am aware of (in the data or from other knowledge) that tells me that the UK should accept entrenched unemployment. I repeat – the problem facing Britain is that there is not enough demand for labour which in the derived sense means there is not enough overall spending in that economy. The short-side of the market is demand not supply.

Conclusion

The real macroeconomy links spending to output to employment. Output growth creates income growth because firms have to hire workers (and other inputs) in order to produce.

If some of that income doesn’t come back to firms in the form of spending then the firms will revise their production decisions downwards.

Household saving, for example, is one way that the income paid is not recycled back into renewed output. Imports and taxation are the other demand “leakages”.

When exports and private investment are not sufficient to match these leakages the only way the economy can continue without recession is if the government sector meets the spending shortfall.

That is the way income growth occurs.

That is enough for today!

Still waiting for the sectoral data which doesn’t get released until October 25th – a full four months after the end of the second quarter.

I hope these ONS changes allow them to speed up the data releases in future quarters.

Grumble, grumble.

Let’s just keep hitting our heads with these hammers until all our headaches are cured!

Very clear exposition. Thanks. Answers a question I put on a previous Comment.

Hi

It seems to me that so called easing is taking place from time to time. What are governments trying to ease?

Another angel onto the end of the pin.