I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Tripping over one’s ideological shoe laces

I’m sitting here at the airport typing away while the morning TV news in the background is showing the Australian Treasurer acknowledging that the economy is slowing and undermining his obsessive desire to achieve a budget surplus next year. Tax revenue continues to decline as activity stalls. Why? Because the Government withdrew the fiscal stimulus too early which caused real GDP growth to stall. Not to be beaten though the resolute Treasurer is now exploring further spending cuts to get the budget “back on track to surplus”. Its high comedy in one sense but high tragedy in the real sense – that unemployment is rising and employment growth falling. But the Treasurer is running with the rest of the G-20 Finance ministers and they are all tripping over their ideological shoe laces

The Australian Government released the – Final Budget Outcome, 2010-11 – today and the results have been headline news all morning. The publication shows that:

1. “In 2010-11, the Australian Government general government sector recorded an underlying cash deficit of $47.7 billion (3.4 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP)). The fiscal balance was in deficit by $51.5 billion (3.7 per cent of GDP).”

2. “In cash terms, the final budget outcome for 2010-11 was $1.6 billion lower than the underlying cash deficit estimated at the time of the 2011-12 Budget, with total cash receipts (excluding Future Fund earnings) $2.0 billion lower than expected and total cash payments $3.6 billion lower than expected.”

3. “Tax receipts in 2010-11 came in around $40 billion (13 per cent) below the level that was forecast in the 2008-09 Budget before the crisis.”

The reason? Our economy is growing much more slowly than expected. Any concern? The deficit is not large enough!

The Treasury claims that the “recent natural disasters subtracted 3/4 of a percentage point from real GDP growth in 2010-11, driven by substantial production losses in the mining and agricultural sectors. The production losses, in turn, lowered tax receipts significantly.”

In the 2010-11 Budget, the Government said:

The Australian economy is expected to grow by 3 per cent in 2010-11

From the National Accounts we learn that the economy actually grew by a miserable 1.3 per cent over 2010-11 financial year. So even if the impact of the recent natural disasters (3/4 of a percentage point) is accurate there was still a shortfall of some nearly 1 per cent from the forward estimates.

This shortfall is more or less attributable to the government failing to appreciate the poor state of private spending and hence, driven by their surplus obsession, withdrawing the fiscal stimulus too early.

There is no question that the fiscal stimulus was withdrawn before private domestic sector spending could support stronger growth.

While the Budget document for 2010-11 said “Expected strong investment, largely associated with the mining boom, continues to underpin the positive growth outlook” and that “The global economy is continuing to recover”. Neither statement has been fully realised. The external sector continues to subtract from growth and the world economy is now slowing.

The ABC News coverage carried the headline – Swan unveils $48b deficit – at which point the Treasurer of the Year, Wayne Swan should have said well given the high unemployment and underemployment, the falling participation rate and the poor employment growth I am disappointed that the deficit is as low as it is.

What did the erstwhile Treasurer say to the Press:

We’ll have softer revenues going forward as a consequence of the global instability … All of that will make it more difficult to reach surplus in 2012-13 but we are absolutely determined to do that.

Absolutely determined!

I suppose that is the resolve one would expect from the Euromoney Magazine Finance Minister of the Year

Euromoney recently bestowed that title on Wayne Swan which he gleefully accepted although one might form the view that it is a booby prize.

There is a book we all read when we were young by Donald Horne – The Lucky Country – which was published in 1964. The opening line of the final chapter read:

Australia is a lucky country, run by second-rate people who share its luck.

The Australian government site promoting the book (as a cultural icon) says “That sentence was a rather brutal indictment of his country at the time. It is a direct, uncompromising and seemingly unambiguous commentary on Australia in the 1960s. Horne was critiquing an Australia that did not think for itself; a country manacled to its past; and ‘still in colonial blinkers’: ‘If we are to remain a prosperous, liberal, humane society, we must be prepared to understand the distinctiveness of our own society’.”

Not much has really changed. In economic terms, the Australian government is caught hook-line-and-sinker in the neo-liberal web. The Labor government is meant to be the political arm of the workers but is indistinguishable from the conservatives on matters economic. They argue relentlessly about who will generate the biggest budget surplus, which both misrepresent as prudent governance.

The is why the Euromoney prize is a booby prize – it goes to the least qualified Treasurer in terms of ensuring the economy functions to produce enough work and prosperity for the workers rather than the bosses. It must have been a tough choice this year – given the long queue of finance ministers imbued with fiscal austerity who daily go about undermining their own economies with spending cuts.

But the Treasurer was resolute today. In the face of the evidence that the cyclical stabilisers are undermining his discretionary choices the Treasurer said that he is absolutely determined to generate a surplus in 2012-13. He will not achieve that aim and in attempting to achieve it is likely to cause further damage.

He was out in the media today relentlessly saying the same thing.

He used terms such as:

Australia’s budget position “remains amongst the strongest in the developed world”

A budget can neither be strong nor weak. It doesn’t make any sense to say that. Would a budget deficit of 4 per cent of GDP be stronger than a budget deficit of 5 per cent of GDP? What would that possibly mean?

Imagine that the 5 per cent case was associated with strong discretionary fiscal stimulus sustaining steady growth and full employment with the non-government sector hitting its desired saving target.

Contrast that to a 4 per cent case where the automatic stabilisers were driving the budget outcome and growth was stumbling and unemployment was rising. Further the economy was coming up against a demand deficiency courtesy of the non-government sector trying to save but being frustrated by the government trying to pursue a surplus at all costs.

Which situation is stronger? Clearly the former. Which means we can make no sense of a comparison between budget outcomes.

He went on to say:

These figures demonstrate that the budget is in good shape particularly with low debt and that is one of the reasons Australians can be so confident that our economic fundamentals are strong.

The figures do not demonstrate anything about quality (“good shape”). They tell us that in the financial year 2010-11 there was a net spending flow from the public sector to the non-government sector of some $A51.5 billion, equivalent to 3.7 per cent of GDP.

Was that spending flow appropriate relative to the non-government spending flows? Was the GDP rate of growth a desirable rate? Was there full employment?

You can see that quoting some budget outcome without any context at all tells us nothing about whether the economy is in “good shape”. The only health we should be concerned about is the health of the real economy (with consideration given to price stability – that is nominal value stability).

As noted above a 5 per cent, 3.7 per cent. 0 per cent budget deficit outcome tells you nothing.

Further, the public debt level provides no indication of the health of the economy or the “strength” of the economic fundamentals. Given the modern practice of issuing debt to match the net spending (deficit), and even issuing debt when there are surpluses to satisfy the vested interests in the futures markets, you get into the same tangle that you get into when trying to determine whether a 5 or 4 per cent deficit is “better”.

The Opposition was even more embarrassing. The shadow treasurer (acting) tried to claim the government was publishing the data today so that it would be drowned in the media attention arising from the fact that tomorrow the two major football codes have their grand finals. He said:

These are the two worst consecutive budget deficits in the nation’s history. We’ve got a situation where this government has never delivered a surplus, and I don’t think it will ever deliver a surplus.

Which tells you how moronic the conservatives are? For overseas readers, the current government took office in late 2007 not long before the crisis hit. The previous conservative government ran 10 surpluses in 11 years and claimed they were the exemplar of responsibility. They forget to mention that during that time, the private domestic sector ran up record debt levels and are now using the public deficits to run down their excesses (by saving).

I actually hope the Opposition spokesperson is correct – that the government never delivers a surplus.

The Finance Minister Penny Wong was also doing the rounds of the press today telling ABC news, for example, tha in the light of collapsing revenue that:

… savings had been found across the budget to make that possible.

The Treasurer concurred and noting that the global economy was slowing dramatically said:

‘It means we do expect … that we’ve got a significant savings task in front of us.’

The little puppets – someone, presumably, takes them out the back occasionally and rewinds them and releases them back into the public.

“We love surpluses, revenue is falling, it is not our fault, but we love surpluses, we have to cut spending even further”.

And all the children then scream – remember at pantomimes when the bad guy would come out of the wings the kids were all trained to scream and point. What did they scream: “the more you cut spending, the less we will spend”.

To which the Treasurer replies: “I am absolutely determined to get a surplus”.

When interviewed about the Euromoney award by the ABC, the Treasurer noted:

… the award is for is the Australian response to the Global Financial Crisis because, as you know, we’re one of the few advanced economies that avoided recession, and since that time there’s been something like 750,000 jobs created in Australia and that’s what counts for me.

Well the Finance Minister hasn’t got his arithmetic quite right. Since the downturn began (February 2008 was the low-point unemployment rate month for the last cycle), the Australian labour market has added in net terms 634.8 thousand jobs. But he forgets to mention that the labour force has risen by 825.6 thousand workers meaning that employment growth hasn’t kept pace with the supply of labour.

The result – unemployment has risen by 190.4 thousand – hardly something to glow about.

Further, he forgets to mention that of the (deficient) employment growth, 54 per cent of the net employment added have been part-time jobs and increasingly casualised and not offering the desired hours (so underemployment has risen).

Moreover, over that time the 15-19 year olds have actually lost 58.5 thousand jobs (as at August 2011) compared to February 2008.

The following graph is taken from the Australian Bureau of Statistics Labour Force data and shows Australian employment growth since July 2009 (to August 2011). The solid positive growth was driven by the fiscal stimulus and as it was withdrawn the economy has slumped.

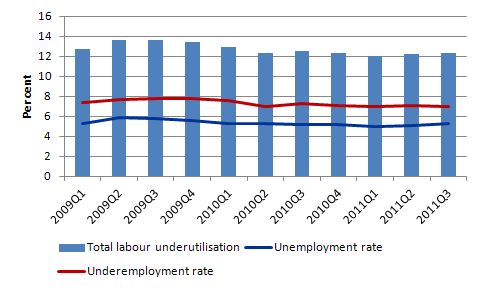

The other side of this is inability of the economy to reduce the very high rates of labour underutilisation. The following graph shows the evolution of the ABS broad labour underutilisation rate and its components unemployment and underemployment over the same period and broad underutilisation remains stuck at 12.3 per cent having dropped by 0.4 per cent in the period shown. The unemployment rate has risen and underemployment rate has fallen a little.

Essentially, the so-called “recovery” has not seen any significant reduction in the rate of labour wastage in Australia.

But it is actually worse than the previous graphs suggest. Some might ask: if employment growth is faltering why hasn’t labour underutilisation risen over this period? The answer lies in the next graph – labour force participation. As the recovery started to gather pace (under the support of the fiscal stimulus packages), the initial drop in labour force participation reversed and more people were coming back into the labour force.

Whenever there is a downturn in economic activity some people exit the “measured” labour force simply because they tell the statistician that they are willing to work but have stopped actively searching. The reason is that there are fewer opportunities and to preserve their self-esteem they give up searching. Economists refer to this cohort as being discouraged workers and they are considered to be hidden unemployed.

They would take a job immediately if it was offered and so are functionally unemployed although the statistician excludes them from the official unemployment count. When things improve this group tends to resume active job search and so the participation rate rises again. So a growing economy may in the early period of recovery actually see the co-incidence of rising employment and unemployment as the employment growth also boosts labour force growth.

You can see that as employment growth faltered, the participation rate which was in a state of recovery headed south again and hidden unemployment rose again. This is why the official unemployment rate is not higher than it would otherwise be (without these cyclical swings in the labour force) and is also why the ABS broad labour underutilisation rate (12.3 per cent) is an understatement of the true labour wastage in the country.

The budget surplus or bust mentality – which is characteristic of neo-liberal thinking – is a sort of cargo cult thinking. They conceive a budget surplus as being like a golden egg which gives them increased capacity to spend in the future.

The reality is clear: a budget deficit now or a budget surplus now provides the government with no more (or less) capacity to spend tomorrow. A currency-issuing government can always spend irrespective of its past budget position.

Further, in all of the public discussions, I have never heard one person who has their hand on the policy levers or would have if they were in office – recognise the contextual nature of the budget balance.

Even among the bank economists I never hear them reveal an understanding and recognition of the way the major sectoral balances – budget, external and private domestic – interact in an accounting sense – which, of-course, is just recording interdependent behaviour. Not once have I heard any one argue that the fiscal rules the government is blindly following without recourse to broader events in the economy is nonsensical.

Let me emphasise – any fiscal rule is nonsensical because the government really doesn’t have the capacity to guarantee performance in relation to it. In fact, in trying to deliver the undeliverable the government is liable to cause more damage (slow growth unduly) than if it just forgot about the budget balance altogether and realised that it is just an ex post record of non-government saving.

While the government can clearly set discretionary spending and revenue aggregates it cannot control the final budget outcome. That depends on non-government spending decisions. If the non-government sector reduces its rate of spending or if the supply-side of the economy contracts (for example, due to floods) and reduces income production (and hence private spending) then the budget balance will move towards or into deficits.

Why? Because the automatic stabilisers (lost tax revenue as activity slows or increased social transfers to ameliorate the income losses in the private communities) will ensure that is the case. This is exactly what is happening in Australia at present.

The withdrawal of the fiscal stimulus on top of the natural disasters have seen revenues collapse and the deficit remain higher than otherwise thought.

But there is no legitimate case that can be made on economic grounds to cut the federal deficit. Growth is languishing and labour underutilisation remains unacceptably high. In fact, the federal government should be seeking to increase the deficit by expanding net spending at present to push the growth rate up to a level that will eat into the massive pool of idle labour.

With an economy that is facing slowdown in private activity there is never a case that can be made to pursue a fiscal rule that will, if successfully achieved, introduce anti-growth fiscal drag.

The requirement that budget outcomes should be some arbitrary balance (surplus) not only restricts the fiscal powers that governments would ordinarily enjoy in fiat currency regimes, but also violates an understanding of the way fiscal outcomes are effectively endogenous. Any economist with even the simplest understanding of the way in which automatic stabilisers operate will see the lack of wisdom in the Treasurer’s statement today.

In Australia, the external sector is typically in deficit (draining growth). As a result of the credit binge, the private domestic sector (principally households) are holding record levels of debt and a very vulnerable to another economic slowdown. The Australian property market is overvalued at present and a correction will come in time which will cause further pain to the heavily indebted household sector.

In this context, a budget deficit is indicated if growth is to continue and the private sector is to have the scope to reduce their debt levels. There is no other option! So to be targetting surpluses in this environment with the need for a major deleveraging in the private sector is equivalent to vandalism.

A sharp negative demand shock which causes an economic downturn will reduce tax receipts and increase benefits, automatically increasing the deficit. Reducing government expenditures in that situation to meet the rule will worsen (prolong) the downturn – that is, increase the output gap and deliberately (and unnecessarily) undermine income generation in the economy.

This dynamic will then see the fiscal ambitions of the government thwarted and the subsequent political fallout is likely to see renewed attempts on its behalf to cut spending even further. That was certainly happening today as the Government amd the conservative opposition jousted about who would generate the bugger surpluses.

The vicious circle of spending cuts implied is unsustainable and is the exemplar of irresponsible fiscal management.

In other words, fiscal policy becomes pro-cyclical under this sort of fiscal rule in the current circumstances (taken into account the context and the forces which drive the budget balance).

Another problem relates to the bias in the way fiscal adjustment is conceived. In particular, it is automatically assumed that discretionary actions to reduce the budget deficit will involve spending cuts rather than increasing taxes. I always have the impression that some politicians are not primarily concerned about the size of the budget deficit, but praise the sanctity of these fiscal rules as a welcome excuse to force their ideological predilection for small government.

In other words, the ideological bias against public activity, particularly in the social security sphere, is dressed up as prudential economic management to give the crude religious zeal an air of authority and respectability.

Of-course, many politicians who mouth the same fiscal rule mantras are just plain ignorance.

Please read this blog – Fiscal rules going mad … – for more discussion on this point.

The responsible fiscal response to the crisis is to ensure that fiscal policy fulfills its basic function before anything other – that is, to fill the aggregate spending gap. The only sustainable fiscal policy approach is to ensure that net government spending is sufficient to fund the net saving desires of the non-government sector. End of story.

Thus when there is a positive desire to net save by the non-government sector then the government sector has to be in deficit to ensure there is enough spending left in the system to underwrite production levels consistent with full employment.

For more on this see my blogs on – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 1 – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 2 – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 3

You hear constant references to the term “fiscal room” when you listen to deficit terrorists. This way of thinking just reflects the straitjacket that the neo-liberal approach has the policy world in. The concept of fiscal room is an irrelevant construct unless we consider there are no spare real resources available.

Conclusion

With more than a million workers idle at present (12.3 per cent at least of the total available labour force not including the hidden unemployed) and industry with spare capacity being available (for example, construction) there are stacks of real resources available for deployment.

Saturday Quiz

The Saturday Quiz will be back sometime tomorrow (at 04.00 actually). It is designed to tease and entertain.

Its been a tough week.

That is enough for today!

Horne was being ironical when he chose the title for “The Lucky Country”.Of course,irony of any description is lost on the likes of Swan,Wong and their advisors/toadies/satraps etc.

Whatever “luck” Australia may have had in the past is probably not on the cards still to be dealt given the incredible stupidity,ignorance and arrogance of our “leadership” class.Even if they held a winning hand they wouldn’t know how to play it.

Dear Bill,

Suppose in 2013 there’s a sudden increase in birthrates in a sovereign-currency country (let’s say, originating from a three-day blackout). There will be, accordingly, a corresponding increase in the able-to-work population some twenty years down the road, not unlike the baby boom phenomenon. Can this be considered as a kind of ‘exogenous’ increase of the number of candidates for employment/the unemployed?

One more thing. Your stance, as you’ve repeatedly written and irrespective of MMT, is about the government striving to provide as much ecologically-sustainable jobs as possible (and enticing the private sector to follow suit, through the appropriate programs, etc). But if that’s the case, population control is essential if we are to follow your proposed direction. Otherwise, the set of conditions necessary for the JG application would leave society dependent on factors such as electricity blackouts.

Does this line of thinking carry any merit at all ?

Best regards,

Vassilis Serafimakis

“That was certainly happening today as the Government amd the conservative opposition jousted about who would generate the bugger surpluses”

Typo? Or not? Seems to work either way…

The West’s governments think they are caught between a rock and a hard place: they think that cutting their debt is deflationary because of the tax increases or public spending cuts that seem to be required to get the money with which to repay debts. The flaw in that idea is as follows.

The deflationary effect of borrowing, dollar for dollar, is much less than the deflationary effect of tax. That’s because under the tax option, the private sector’s net financial assets remain constant, whereas under the borrow option, those net assets rise.

If a government wants to fund a given amount of spending from borrowing instead of tax, while leaving aggregate demand (AD) constant, it will have to accompany that with some sort of deflationary measure, like raising interest rates (or doing some “anti-QE”).

If the same government then wants to put the process into reverse, i.e. repay some of its debt while leaving AD constant, it just needs to do the opposite: e.g. raise taxes, repay some debt, while doing some QE.

And as for those who don’t like the so called “money printing” that QE seems to involve, the net effect of the above “run up some debt and then pay it off” is simply to return the country and its money supply to where it would have been had it never borrowed anything, and instead, funded all its spending from tax.

In short, the West’s governments have not worked out how to repay debt while leaving AD constant.

My old sociology tutor once said, in regards to another phenomena, “If a few individuals have a problem then it’s the individual’s problem, if many individuals have the problem then it’s a systemic problem.”

So if the Australian population was aware that 1 in 8 working age Australians is not working, then they might be slower to demonise the unemployed as ‘dole bludgers’ and punish them with a below subsistence Newstart Allowance of $240 a week, compared with rent for room of $150 in Melbourne [Gumtree], or a Disability Pension of $370 per week.

As Beatrice Webb said in 1925