I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Redistribution of national income to wages is essential

It is a public holiday in NSW today – Labour Day – which originates from the “eight hour day movement, which advocated eight hours for work, eight hours for recreation, and eight hours for rest”. History will tell you that on April 21, 1856, the stonemasons and building workers on building sites around Melbourne, Australia (my home town) laid down their tools and marched to Parliament House to call for an 8-hour day. They were successful and were the “first organized workers in the world to achieve an eight hour day with no loss of pay”. Similar action saw the spread of the 8-hour day to the other states. Now Australia is in the farcical situation where 600 thousand workers cannot get any hours of work, 750 thousand cannot get enough, and millions are coerced by employer-friendly industrial relations legislation into working more hours than they desire just to keep their jobs. In recognition of the holiday I will write less than usual! The issue surrhttps://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=16325&preview=trueounding wages and conditions of work are crucial to understanding why the world entered the crisis and why it is persisting. At present policy makers, in response to the disaster that beset them in 2007-08, are skating around the edges of reform and are refusing to recognise that they will have to engage in a wholesale abandonment of neo-liberal policies before sustainable recovery will be possible. There is no more stark demonstration of this reality than in the area of wages.

I have considered these themes before. In several previous blogs – for example The origins of the economic crisis and The top-end-of-town have captured the growth – I have noted that a defining characteristic of the neo-liberal period has been the fall in the wage share in national income in most nations. This has come about because real wages growth has dragged behind productivity growth. The gap between the two represents profits and shows that during the neo-liberal years there was a dramatic redistribution of national income towards capital.

This has been aided and abetted by governments in a number of ways: privatisation; outsourcing; pernicious welfare-to-work and industrial relations legislation (designed to reduce the capacity of trade unions); etc to name just a few of the ways. These ways vary by country.

The problem that arises is if the output per unit of labour input (labour productivity) is rising so strongly yet the capacity to purchase (the real wage) is lagging badly behind – how does economic growth which relies on growth in spending sustain itself? This is especially significant in the context of the increasing fiscal drag coming from the public surpluses or stifled deficits which squeezed purchasing power in the private sector since the late 1990s.

In the past, the dilemma of capitalism was that the firms had to keep real wages growing in line with productivity to ensure that the consumption goods produced were sold. But in the lead up to the crisis, capital found a new way to accomplish this which allowed them to suppress real wages growth and pocket increasing shares of the national income produced as profits. Along the way, this munificence also manifested as the ridiculous executive pay deals and Wall Street gambling that we read about constantly over the last decade or so and ultimately blew up in our faces.

The trick was found in the rise of “financial engineering” which pushed ever increasing debt onto the household sector. The capitalists found that they could sustain purchasing power and receive a bonus along the way in the form of interest payments. This seemed to be a much better strategy than paying higher real wages.

The household sector, already squeezed for liquidity by the move to build increasing federal surpluses were enticed by the lower interest rates and the vehement marketing strategies of the financial engineers.

The financial planning industry fell prey to the urgency of capital to push as much debt as possible to as many people as possible to ensure the “profit gap” grew and the output was sold. And greed got the better of the industry as they sought to broaden the debt base. Riskier loans were created and eventually the relationship between capacity to pay and the size of the loan was stretched beyond any reasonable limit. This is the origins of the sub-prime crisis.

So the dynamic that got us into the crisis is present again and with fiscal austerity emerging as the key policy direction the welfare of our economies is severely threatened. This is a dramatic failure of government oversight.

These dynamics are clearly outlined in the recent UNCTAD Trade and Development Report, 2011. Its depiction of root causes of the current economic problems could note be clearer:

The pace of global recovery has been slowing down in 2011 … In many developed countries, the slowdown may even be accentuated in the course of the year as a result of government policies aimed at reducing public budget deficits or current-account deficits. In most developing countries, growth dynamics are still much stronger, driven mainly by domestic demand.

As the initial impulses from inventory cycles and fiscal stimulus programmes have gradually disappeared since mid-2010, they have revealed a fundamental weakness in the recovery process in developed economies. Private demand alone is not strong enough to maintain the momentum of recovery; domestic consumption remains weak owing to persistently high unemployment and slow or stagnant wage growth. Moreover, household indebtedness in several countries continues to be high, and banks are reluctant to provide new financing. In this situation, the shift towards fiscal and monetary tightening risks creating a prolonged period of mediocre growth, if not outright contraction, in developed economies.

They also highlight distributional issues which are usually suppressed by the conservatives in the public debate but should be at centre-stage.

Wage income is the main driver of domestic demand in developed and emerging market economies. Therefore, wage growth is essential to recovery and sustainable growth. However, in most developed countries, the chances of wage growth contributing significantly to, or leading, the recovery are slim. Worse still, in addition to the risks inherent in premature fiscal consolidation, there is a heightened threat in many countries that downward pressure on wages may be accentuated, which would further dampen private consumption expenditure. In many developing and emerging market economies, particularly China, the recovery has been driven by rising wages and social transfers, with a concomitant expansion of domestic demand ….

Wage growth that is falling short of productivity growth implies that domestic demand is growing at a slower rate than potential supply. The emerging gap can be temporarily filled by relying on external demand or by stimulating domestic demand through credit easing and raising of asset prices. The global crisis has shown that neither solution is sustainable. The simultaneous pursuit of export-led growth strategies by many countries implies a race to the bottom with regard to wages, and has a deflationary bias. Moreover, if one country succeeds in generating a trade surplus, this implies that there will be trade deficits in other countries, causing trade imbalances and foreign indebtedness. If, on the other hand, overspending is enticed by easy credit and higher asset prices, as in the United States before the crisis, the bubble will burst at some point, with serious consequences for both the financial and real economy. Therefore, it is important that measures be taken to halt and reverse the unsustainable trends in income distribution.

Clearly the public debate is in denial of these issues. In the Eurozone, the major adjustment being contemplated is to further drive a wedge between real wages and productivity growth by deliberately attacking wages and working conditions. The Euro bosses seem to think that workers will work harder if they are paid less. They also seem to believe that when real wages are cut there is an incentive for firms to invest in capital that delivers higher productivity.

Neither “belief” is justifiable if you examine the research evidence. When workers’ real wages are under attack morale falls and work effort plummets. Further, when real wages are declining, firms has less incentive to use “less” labour (that is, to invest in highly productive capital equipment). The neo-liberal period has been about the “race-to-the-bottom” and our poor productivity performance and vast pools of idle labour are the manifestation.

The UNCTAD Report notes that “wage shares have declined slowly but steadily over the past 30 years” which is “creating hazardous headwinds in the current recovery” for the reasons I outlined earlier – a reduction in the capacity of workers to fund output growth out of wages.

The other point is that in developing countries the reverse has been occurring – and “real wages have been growing, in some instances quite rapidly”. It isn’t surprising that these nations weathered the global crisis more easily than the developed countries which saw substantial declines in the wage share and flat real wages growth. The reason is that recovery “was driven by an increase in domestic demand, and that real wage growth has been an integral part of the economic revival”.

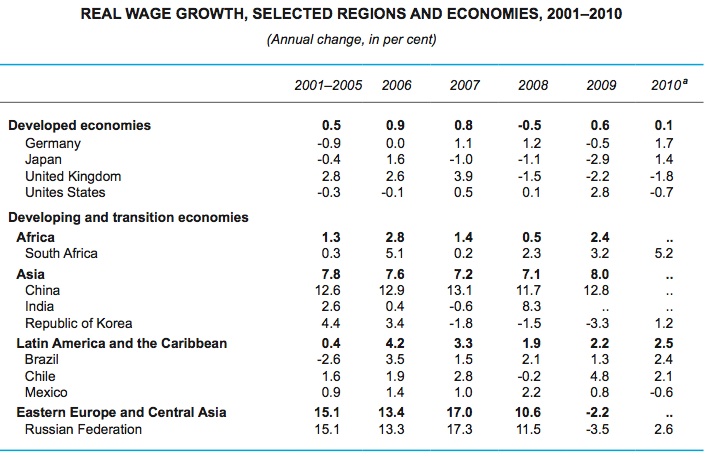

The following table is taken from Table 1.4 in the UNCTAD 2011 Trade and Development Report and is self-explanatory.

At present, the persistently high unemployment in many nations (coupled with the rising underemployment) is deflationary and providing a curb on consumption growth. Then there are those who advocate further cuts in real wages to stimulate employment. On top of that, the overriding agenda of the IMF and OECD is to impose “structural reform” onto nations which really is about redistributing bargaining power further to the employers.

These trends and proposals are the anathema of what is required to stimulate growth.

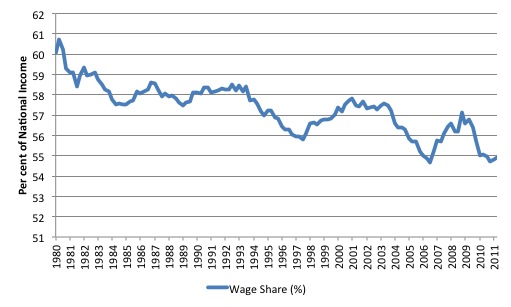

The following graph shows the evolution of the US wage share since March quarter 1980 (to June quarter 2011).

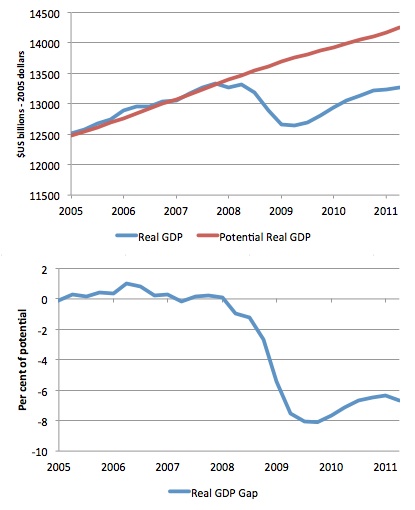

Then consider that there is a vast output gap at present in the US which is depicted in the following graph. The data is taken from the St. Louis Federal Reserve FRED repository, which is an excellent portal for graphing and examining data “on-the-fly” prior to downloading.

The top panel is the comparison of Real GDP ($US billions in 2005 dollars) and Potential Real GDP from March quarter 1980 to the June quarter 2011. The bottom panel is the difference between the potential and actual real GDP in percentage terms (expressed as a proportion of the potential).

A comparison with previous US recessions would show that this gap is quite exceptional in size and duration. The other point that is the potential growth path will eventually be impacted (negatively) by the stagnant actual growth. Firms are currently refraining from investing because of a lack of demand and this will eventually lower the potential real GDP.

But we should never be in any doubt as to what this output gap represents. It signifies lost real income opportunities. These losses are foregone forever. The longer the output gap persists the larger are the costs of the recession (in narrow income terms).

This is perhaps why Martin Wolf in his recent Financial Times article (September 29, 2011) – Time to think the unthinkable and start printing again – says that:

It is the policy that dare not speak its name: the printing press. The time has come to employ this nuclear option on a grand scale. The alternative is likely to be a lost decade. The waste is more than unnecessary; it is cruel. Sadists seem to revel in that cruelty. Sane people should reject it. It is wrong, intellectually and morally.

Apparently, Martin Wolf has finally realised that the fiscal austerity is actually damaging the world economy and there is an urgent need for a renewed fiscal stimulus. It was obvious that the stimulus packages that were applied in 2008-09 were insufficient and should never have been withdrawn. It takes some people longer to realise that – but better late than never.

Martin Wolf’s about face is being hailed as a breakthrough by some – at last. I just think it is sad that someone with so much influence could have ever argued anything different in the face of overwhelming evidence that is seemingly now being (finally) accepted.

Anyway, now we read from Martin Wolf that he:

… would favour the “helicopter money”, recommended by that radical economist, Milton Friedman. This would be a quasi-fiscal operation. Central bank money could pass via the government to the public at large. Alternatively, the government could fund itself from the central bank, directly. Better still, the government could increase its deficits, perhaps by slashing taxes, and taking needed funds from the central bank. Under any of these alternatives, the central bank would be behaving like any other bank, creating money in the act of lending.

There is a lot of mis-information about what “helicopter” drops are about. Milton Friedman thought they were a monetary policy initiative -“printing money” whereas they are really fiscal operations because unlike standard monetary operations (such as open market operations) they change the net worth of the non-government sector which is exactly what a fiscal operation (spending and/or taxation does).

Friedman conceived the central bank dropping money from a helicopter to the awaiting hands of consumers etc as a means of stimulating aggregate demand (spending). The initiative would be equivalent to the central bank (or treasury instructing the central bank) to credit private bank accounts to the tune of $X.

Both policies would increase the stock of net financial assets in the non-government sector and bost its net worth. They also pose an issue for the central bank in its monetary policy settings.

Briefly, should the central bank be targetting a positive short-term interest rate, then it would have to either pay a return on excess bank reserves or sell government bonds to drain the excess reserves after it had engaged in a helicopter drop (or its equivalent). This is because the policy intervention will result in an increase in bank reserves which will stimulate competition in the interbank market and push the overnight rate down to zero.

How does that work? After the helicopter has passed over, people will take the funds to their banks and deposit them. Alternatively, they might spend the funds and the shops will deposit the funds with their banks. Either way, the banks will have more reserves than they require for clearing purposes. Banks can sell currency to the central bank in return for reserve balances. The competition between banks to rid themselves of these reserves drives the interest towards zero.

There is an interesting and short note from Scott Fullwiler on this topic – Helicopter Drops are FISCAL Operations – which goes into more detail on this point.

The other aspect of the immoral nature of the current situation is that these output gaps are being largely borne by workers. Please read my blog – The top-end-of-town have captured the growth – for more discussion on this point.

I did some digging to provide some recent evidence to further underpin that claim. It is not hard to find it.

You can get data from the St. Louis Federal Reserve FRED facility, which is an excellent portal for graphing and examining data “on-the-fly” prior to downloading.

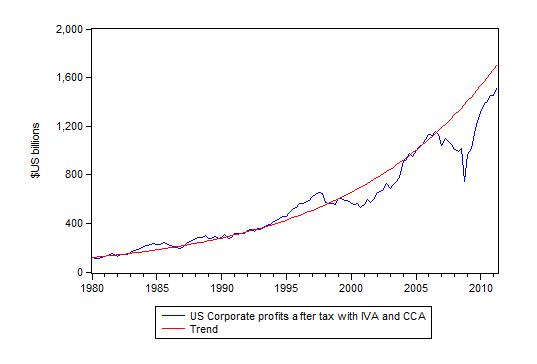

The following graph shows Corporate profits after tax with the IVA and CC adjustment series (CAPATAX) compared to its longer-term trend growth. The data is taken from the US National Accounts published by the US Bureau of Economic Analysis.

We learn that “Inventory Value Adjustment (IVA) and Capital Consumption Adjustment (CCA) are corrections for changes in the value of proprietor’s inventory (goods that may be sold within one year) and capital (goods like machines and buildings that are not expected to be sold within one year) under rules set by the U.S. Internal Revenue Service (IRS).”

On an annual basis this series has grown on average at 7.5 per cent. Starting at the March quarter 1980, I created a trend growth series (red line) and graphed it against the adjusted corporate profits series.

What you learn from this is that in the early stages of the crisis corporate profits slumped as growth came to a halt and you can see the impact of that in both the following graph and also in the rise in the wage share in the graph presented earlier. But as growth has resumed, the corporate profits series has nearly returned to trend while the wage share continues to fall.

In other words, what growth there has been since the downturn has been largely captured by capital. Workers have not shared in that growth much at all which explains why consumption is so subdued. The subdued consumption, in turn, reduces the incentive by firms to invest and so they are “cashed up” more than usual at present.

The major redistribution of national income over the neo-liberal period has been the source of funding for the dramatic expansion of the now (over-sized) financial sector. The reality is that much of the redistributed real income did not return as investment spending but was rather used to buy the gambling chips that the financial sector gambled with.

There will be massive resistance from that sector to government attempts at re-regulation and redistribution of national income back to workers.

The UNCTAD Trade and Development Report is also insightful when it comes to dealing with the financial markets:

Those who support fiscal tightening argue that it is indispensable for restoring the confidence of financial markets, which is perceived as key to economic recovery. This is despite the almost universal recognition that the crisis was the result of financial market failure in the first place. It suggests that little has been learned about placing too much confidence in the judgement of financial market participants, including rating agencies, concerning the macroeconomic situation and the appropriateness of macroeconomic policies. In light of the irresponsible behaviour of many private financial market actors in the run-up to the crisis, and costly government intervention to prevent the collapse of the financial system, it is surprising that a large segment of public opinion and many policymakers are once again putting their trust in those same institutions to judge what constitutes correct macroeconomic management and sound public finances.

And on the need for fiscal policy to support a process of national income redistribution back to workers, the UNCTAD report also has sound advice:

… there is a widespread perception that the space for continued fiscal stimulus is already – or will soon be – exhausted … There is also a perception that in a number of countries debt ratios have reached, or are approaching, a level beyond which fiscal solvency is at risk.

However, fiscal space is a largely endogenous variable. A proactive fiscal policy will affect the fiscal balance by altering the macroeconomic situation through its impact on private sector incomes and the taxes perceived from those incomes. From a dynamic macroeconomic perspective, an appropriate expansionary fiscal policy can boost demand when private demand has been paralysed due to uncertainty about future income prospects and an unwillingness or inability on the part of private consumers and investors to incur debt.

In such a situation, a restrictive fiscal policy aimed at budget consolidation or reducing the public debt is unlikely to succeed, because a national economy does not function in the same way as an individual firm or household. The latter may be able to increase savings by cutting back spending because such a cutback does not affect its revenues. However, fiscal retrenchment, owing to its negative impact on aggregate demand and the tax base, will lead to lower fiscal revenues and therefore hamper fiscal consolidation … Moreover, making balanced budgets or low public debt an end in itself can be detrimental to achieving other goals of economic policy, namely high employment and socially acceptable income distribution.

These are all words that can speak for themselves with no further prompting or intervention from yours truly.

UNCTAD also show that where fiscal tightening was implemented (especially under the auspices of the IMF) during the 1990s and 2000s the budget “deficit actually became worse, often sizeably, due to falling GDP”.

Conclusion

The point here is all the aspects of the neo-liberal era have to be addressed by governments if sustainable growth is to return. The banks have to be fixed. Excessive reliance on monetary policy has to be overcome in favour of more systematic use of counter-stabilisation fiscal policy.

But also work has to be done on the distributional frontier and profits have to be cut and real income redistributed back to workers so that real wages grow more or less in line with productivity growth.

The UNCTAD Report also provides sound advice on the ways in which governments have to re-regulate the financial sector to ensure that they work for the real economy and not the other way around. I will consider those proposals in another blog.

And seeing as though it is a holiday …

That is enough for today.

Well that was what I thought too. For about 10 years I was wondering what was going wrong, a gnawing discomfort in my gut.

It shouldn’t be so, but I’m quite surprised an article by an esteemed international organization agrees with Bill (or should it be the other way around). What does UNCTAD do to keep the neoliberals at bay….strings of Garlic?

Please define “sustainable growth”.

It should be obvious that,in a finite system,which is our spaceship Earth,growth can’t be infinite as the Growth At Any Cost Crowd are so fond of imagining and also of inflicting their vanities on the Earth and its passengers.

In the same finite world most of what is imagined to be sustainable growth is no such thing no matter what sort of technocopian delusions are indulged in by the proponents.

This would seem to me te be the crux of our problems and no amount of fiddling around the edges will achieve anything except kick the can a bit further down the road.This will result in even more grief down the road.

Agree with your post, but I have a question relating to your second graph, on U.S. actual and potential GDP.

You write:

“But we should never be in any doubt as to what this output gap represents. It signifies lost real income opportunities. These losses are foregone forever. The longer the output gap persists the larger are the costs of the recession (in narrow income terms).”

No one would take a line drawn through the peak of U.S. output in 1929 — the beginning of the Great Depression — and say that output has lagged ever since then because it never recovered its pre-1929 “trend” line. Why should such a line be drawn at the peak of the 2008 bubble as a measure of “potential” GDP?

If GDP is the result of consumption and investment, and both are fed not solely by “income” and “profits” but by debt, in what sense is it “potential”? Presently, that debt must (largely) be repaid — unless the public sector is going to make up the difference and effectively re-inflate the bubble. I suppose in theory the public sector could repay everyone’s debts, but how realistic is it to imagine any government (no matter what its external balance) doing so? Could housing really have continued to expand at the same rate, given absolute demand from this presently sized population? Supply must have *some* relationship to real demand.

The same graph is often used by Krugman and Delong to demonstrate a point about cyclical vs. structural unemployment. I have no doubt that fiscal policy (or helicopter drops) could mitigate unemployment. But I don’t understand how, even if wages had kept up with productivity, the price levels of the bubble (which measure GDP) should necessarily have conformed to some historical trend line that included so much debt.

To put it a different way, there is no guarantee that any divergence from the historical trend does not reflect a real structural change in any economy.

Someone, please clarify.

Here’s a brain teaser. The structural deficit is that part of the deficit which is not designed to bring stimulus. Or as the Wiki definition puts it, the structural deficit “exists even when the economy is at its potential”.

Therefor to the extent that “consolidation” consists of disposing of the structural deficit, there would not be a deflationary effect (contrary to the claims of UNCTAD). Where’s the flaw in that argument?

@Joel: I think a good way to interpret the graph is to think of it as representative of lag w.r.t. where the economy could have been during the interpolated divergent period. It’s actually very similar to a velocity over time graph, where the area under the graph is equivalent to the distance covered. The real vs potential GDP graphs are akin to two cars that start off accelerating at the same rate, but then one trails off. Even if the one behind recovers after some time and begins accelerating at the same rate and even attains the same speed, it will not have covered the same distance for any given time. That difference in distance is “permanently” lost. Not sure if that helps, and I will of course defer to Bill, but that’s my take on it (sans great depression as a frame of reference).

There is a lot of mis-information about what “helicopter” drops are about.

Indeed. Bill, I would love to see you devote a post to the “market monetarists” and some of their blogospheric monetarist fans, who sometimes seem very confused about this and other real-world central bank mechanisms, and go on about rational expectations, inflation targeting, NAIRU, Phillips curves, etc.

Ralph,

“Therefor to the extent that “consolidation” consists of disposing of the structural deficit, there would not be a deflationary effect (contrary to the claims of UNCTAD). Where’s the flaw in that argument?”

I think we have spoken about this before, and it was you and Bill that made me understand: the flaw is not in the argument, but in the assumption that the structural deficit actually exists, given its entirely theoretical construction – for all anyone knows it may be (and probably is) a structural surplus.

My own point of view is that, providing the government spends enough to lower unemployment and generate growth, without causing accelerating inflation, then that spending is appropriate. Any academic assessment beyond this is irrelevant.

Thanks, Marley.

As it happens, someone else’s comment on Brad Delong’s blog made me reformulate my question about potential GDP trend lines. I hope this second attempt isn’t beating a dead horse.

“TC said…

Note that even if we use credit to purchase these goods, the real economy still produced them. It means that the real economy can afford to produce them. In aggregate, We can’t produce more than the real economy can afford.

We might be producing the wrong things, but that doesn’t mean we can’t afford this level of production.”

“jcb said in reply to TC…

Thanks. Your post helps me clarify why I don’t understand that debt-fueled measurement of GDP should be included as a realistic social measure of “potential” output.

It is true that the real economy did “afford to produce” these goods. And it is true that “we can’t produce more than the real economy can afford.” But we also can’t necessarily consume everything that the real economy can afford to produce. In theory, we could afford to produce houses at the rate they were being produced during the bubble. And this would include all the housing produced in anticipation of demand that never did (and never could, at this population size and wealth structure) materialize.

For this rate of production to continue, the public sector would have to 1. assume or pay off the accumulated debt of the private sector, 2. supply the demand previously supplied by private credit.

The result would be a lot of empty houses — as is reportedly the case in China, where the government has supported private debt:

http://www.nytimes.com/slideshow/2010/10/19/business/global/20101019-ghost-slideshow.html

Considered as a solution to the unemployment problem, supply without demand would certainly work. Strictly from a resource conservation standpoint, however, it probably would not — that is, the resources might be exhausted in the future when an appropriately sized population (with an appropriately sized income) could afford to purchase them.”

“Potential” ought to mean that, under some reasonable set of assumptions about the current economy (population size, resource availability, income level), demand would (roughly) equilibrate with supply.

“The household sector, already squeezed for liquidity by the move to build increasing federal surpluses were enticed by the lower interest rates and the vehement marketing strategies of the financial engineers.”

How about price and wage expectations from the 1970’s instead of from the 1930’s?

“Redistribution of national income to wages is essential”

So why not put some more people into retirement to tighten up the labor market?

“Firms are currently refraining from investing because of a lack of demand and this will eventually lower the potential real GDP.”

It seems to me they are still investing a little to attempt to increases sales and some to increase productivity (meaning even fewer workers are needed). They aren’t investing to increase capacity.

“It signifies lost real income opportunities.”

Or lost retirement?

“Under any of these alternatives, the central bank would be behaving like any other bank, creating money in the act of lending.”

savings of the rich = dissavings of the gov’t (preferably with debt) plus dissavings of the lower and middle class (preferably with debt)

The solution to too much lower and middle class debt owed to the rich is not more gov’t debt owed to the rich and not more lower and middle class debt owed to the rich.

Moreover, making balanced budgets or low public debt an end in itself can be detrimental to achieving other goals of economic policy, namely high employment and socially acceptable income distribution.”

Not if medium of exchange is looked at like this:

savings of the rich plus savings of the lower and middle class = the balanced budget(s) of the various level(s) of gov’t plus the dissavings of the currency printing entity with currency and no bond/loan attached.

Where does this idea come from that all NEW medium of exchange has to be the demand deposits created from debt whether private debt or gov’t debt?

While I agree that in Western nations the wage share has been going down while the profit share has been going up, I don’t see that the former necessarily follows from the latter. What about the tax share?

“Where’s the flaw in that argument?”

You can’t measure the structural deficit.

Structural Deficit is up there with NAIRU. Concepts designed to frame debates and control thoughts but of no use at all in designing a system because they cannot be measured directly.

The ‘estimates’ given for these fictitious concepts are based upon religious belief rather than hard science and are used to reinforce the ideology.

All government spending pays for itself for any positive tax rate where there are free real resources to service the transaction sequence – you either get the tax back or you get savings. There can be no ‘structural deficit’ until real resources become scarce enough to require a constraint of spending.

Hi Bill,

which data series did you use to calculate the wage share of national income (first graph of this blog). Tried to replicate it on the St Louis Fed site…and failed….

Thanks and best wishes

Tomme

@FedUp: It seems to me they are still investing a little to attempt to increases sales and some to increase productivity (meaning even fewer workers are needed). They aren’t investing to increase capacity.

That is my impression also. How much of a factor do you think health care costs are playing?

Charles J and Neil, Re the idea that structural deficits don’t exist, you are saying in effect that it is a physical impossibility for a government to fund its spending from borrowing INSTEAD OF from tax (i.e. with no intention to provide stimulus ). All I can say is that if there are any politicians out there who don’t know how to do the latter, I’ll explain how (in exchange for 1% of the total amount involved). But the reality is that politicians are all too adept at failing to collect enough tax.

For example in the US between about 1985 and 95 (Bush/Regan) the national debt rose sharply despite unemployment being on the low side compared to now. So stimulus cannot have been the motive or main motive for those deficits. The actual motive I suggest was that Bush and Regan were ingratiating themselves with the electorate by collecting insufficient tax, and borrowing instead.

As for the idea that trying to estimate the size of the structural deficit is not important, what if a country is at full employment and has a rapidly expanding national debt? In that scenario, the responsible reaction would be “the deficit is largely structural, so we’d better rein it in, cut borrowing and raise taxes”.

“what if a country is at full employment and has a rapidly expanding national debt?”

And what if it doesn’t?

As I said above: “There can be no ‘structural deficit’ until real resources become scarce enough to require a constraint of spending.”. Either public or private.

Absolutely!

The way things are at present, if we mechanised all production there would be no-one with any money to buy anything. Crazy.

It seems so obvious to me that we need share work out……and the benefits, of course. What happened to the promise of mechanisation? Stolen, by those at the top.

Dan Kervick said: “That is my impression also. How much of a factor do you think health care costs are playing?”

For rich people and rich businesses, it seems there has been very little effect.

For small businesses, there probably has been some, but low demand seems to be a bigger problem.

For the lower and middle class, that is where the biggest effect probably is. It is affecting their budgets and demand too.

last_name_left, exactly.