I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Why we should abandon mainstream monetary textbooks

I have noticed some discussions abroad that criticise Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) on the basis that none of the main proponents have ever actually worked on the operations desk of a central bank. This sort of criticism is in the realm of “you cannot know anything unless you do it” which if true would mean almost all of the knowledge base shared by humanity would be deemed meaningless jabber. It is clearly possible to form a very accurate view of the way the monetary system operates (including the way central banks and the commercial banks) interact without ever having worked in either. However, today, I review a publication from the Bank of International Settlements which dovetails perfectly with the understandings that MMT has provided. It provides a case for why we should abandon mainstream monetary textbooks from the perspective of those who work inside the central banking system.

I would not want it thought that I think that practical experience isn’t valuable. Clearly a mix of research and analysis and practical experience is useful in developing an understanding of how things operate in the real world. MMT has, in fact, evolved via the interaction of academic and financial market players and is quite unlike most academic theoretical development in economics.

Sometimes we have to look beyond the superficial relations that confront us in a practical manner though. For example, while the arrangements of government that the legislature has put into place may require from an accounting sense that funds taken from the private sector go into a specific central bank or treasury account prior to funds from the government sector being withdrawn from that account and spent into the non-government sector this doesn’t mean that governments require in any operational sense the private funds before it can spend.

Intrinsically, a sovereign government issues the currency so it is never revenue constrained. MMT brings that sort of duality into relief. While the mainstream leave the impression that the private sector funds the government and then spins a number of related stories about that which make it difficult for people to accept that government spending is useful, it would be a different narrative if we all knew that the institutional arrangements surrounding debt-issuance (for example) were just voluntarily-imposed structures that were ideologically based on the presumption that government deficits were inherently bad.

So if we knew that the analysis that declares government deficits bad was actually based on an assumption that it was bad rather than any intrinsic financial constraint then the debate would be different.

MMT aims, in part, to expose these faux starting points so we can differentiate between a financial constraint and a political/ideological constraint more clearly.

But it is also useful when a central banking institution publishes material that is consistent with the core tenets of MMT. It is hard to then label the views as emanating from a small clique.

In February 2010, the Bank of International Settlements published Working Paper No 297 – The bank lending channel revisited (thanks Luigi).

The paper challenged the “central proposition” of mainstream “research”:

… that monetary policy imparts a direct impact on deposits and that deposits, insofar as they constitute the supply of loanable funds, act as the driving force of bank lending. These ideas are manifested most clearly in conceptualizations of the bank lending channel of monetary transmission, as first expounded by Bernanke and Blinder (1988). Under this view, tight monetary policy is assumed to drain deposits from the system and will reduce lending if banks face frictions in issuing uninsured liabilities to replace the shortfall in deposits. Essentially, much of the driving force behind bank lending is attributed to policy-induced quantitative changes on the liability structure of bank balance sheets.

If you read almost any university-level macroeconomics or monetary economics textbook you will find narrative along these lines. The story is that the central bank controls the money supply via open market operations (buying and selling bonds) and that bank lending is reserve (deposit) constrained.

This narrative employs “either on the concept of the money multiplier or a portfolio-rebalancing view of households’ assets”.

To see the MMT view of the money multiplier – please read my blogs – Money multiplier and other myths and Money multiplier – missing feared dead.

The BIS paper notes that the mainstream believe that “changes in the stance of monetary policy are implemented through changes in reserves which, in turn, mechanically determine the amount of deposits through the reserve requirement”.

Alternatively, the mainstream “portfolio-rebalancing” approach posits that “monetary policy actions alters the relative yields of deposits (money) and other assets, thus influencing the amount of deposit households wish to hold”.

Whichever approach is adopted, the narrative says that monetary policy tightening reduces the deposits in the system, which means that banks have to rely on more expensive wholesale funding, and as a result the supply of credit declines.

In other words, “changes in deposits are seen to drive bank loans”.

MMT has provided a comprehensive challenge to that view of banking based upon a thorough analysis of how banks actually operate and practical experience of banking which reinforces the conceptual development.

Please read (among other blogs) – The role of bank deposits in Modern Monetary Theory and Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion.

Banks do not need reserves to lend? The mainstream view is that reserves are deposits that haven’t been lend yet. Banks do not lend reserves!

The commercial banks are required to keep reserve accounts at the central bank. These reserves are liabilities of the central bank and function to ensure the payments (or settlements) system functions smoothly. That system relates to the millions of transactions that occur daily between banks as cheques are tendered by citizens and firms and more. Without a coherent system of reserves, banks could easily find themselves unable to fund another bank’s demands relating to cheques drawn on customer accounts for example.

Depending on the insitutional arrangements (which relate to timing), all central banks stand by to provide any reserves that are required by the system to ensure that all the payments settle. The central bank charges a rate on their lending in this case which may penalise banks that continually draw on the so-called “discount window”.

Banks thus maintain reserve management units to daily monitor their status and to seek ways to minimise the costs of maintaining the reserves that are necessary to ensure a smooth payments system.

Banks may trade reserves between themselves on a commercial basis but in doing so cannot increase or reduce the volume of reserves in the system. Only government-non-government transactions (which in MMT are termed vertical transactions) can change the net reserve position. All transactions between non-government entities net to zero (and so cannot alter the volume of overall reserves). I explain that in more detail including the implications of that point in the trilogy of blogs – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3. The blogs helps to explain why budget deficits place downward pressure on interest rates – which is contrary to the mainstream macroeconomics textbook depiction captured by “crowding out”.

The important point is that when a bank originates a loan to a firm or a household it is not lending reserves. Bank lending is not easier if there are more reserves just as it is not harder if there are less. Bank reserves do not fund money creation in the way that the money multiplier and fractional-reserve deposit story has it.

Bank loans create deposits not the other way around. These loans are made independent of their reserve positions. Adequately capitalised banks lend to any credit-worthy customers.

At the individual bank level, certainly the “price of reserves” will play some role in the credit department’s decision to loan funds. But the reserve position per se will not matter. So as long as the margin between the return on the loan and the rate they would have to borrow from the central bank through the discount window (the worst case scenario) is sufficient, the bank will lend.

So the idea that reserve balances are required initially to “finance” bank balance sheet expansion via rising excess reserves does not capture the way the banking system operates. A bank’s ability to expand its balance sheet is not constrained by the quantity of reserves it holds or any fractional reserve requirements. The bank expands its balance sheet by lending. Loans create deposits which are then backed by reserves after the fact. The process of extending loans (credit) which creates new bank liabilities is unrelated to the reserve position of the bank.

The major insight is that any balance sheet expansion which leaves a bank short of the required reserves may affect the return it can expect on the loan as a consequence of the “penalty” rate the central bank might exact through the discount window. But it will never impede the bank’s capacity to effect the loan in the first place.

So it is quite wrong to assume that the central bank can influence the capacity of banks to expand credit by adding more reserves into the system. If “economic activity is too slow” then the central bank can do very little to expand private credit other than to cut interest rates. The availability of reserves will not increase bank lending. This is the old fashioned money multiplier version of banking where there the “money supply” is some multiple of the monetary base (provided by the central bank).

The BIS paper agrees with this assessment. It says:

… the emphasis on policy-induced changes in deposits is misplaced. If anything, the process actually works in reverse, with loans driving deposits. In particular, it is argued that the concept of the money multiplier is flawed and uninformative in terms of analyzing the dynamics of bank lending. Under a fiat money standard and liberalized financial system, there is no exogenous constraint on the supply of credit except through regulatory capital requirements. An adequately capitalized banking system can always fulfill the demand for loans if it wishes to.

Note the reference to an “adequately capitalized banking system”. I covered that topic in this blog – Lending is capital- not reserve-constrained.

In terms of the money multiplier, the BIS paper goes on to say that:

Inherent in this view, which has a long heritage in monetary economics, is that policy changes are implemented via open market operations that change the amount of bank reserves. Binding reserve requirements, in turn, limit the issuance of bank deposits to the availability of reserves. As a result, there is a

tight, mechanical, link between policy actions and the level of deposits.

Their simple refutation of the money multiplier as a valid description of monetary policy is that central banks express monetary policy through “a target for a short term interest rate”.

In relation to our discussion above about the motives for holding reserves, the BIS paper says that there are two reasons: (a) “to meet any reserve requirement”; and (b) “to provide a cushion against uncertainty related to payments flows.”

In many countries the first motive is redundant because there are no formal reserve requirements. The second motive relates to our discussion above about the integrity of the payments (cheque clearing) system.

The BIS paper concludes that:

The quantity of reserves demanded is then typically interest-inelastic, dictated largely by structural characteristics of the payments system and the monetary operating framework, particularly the reserve requirement. When reserves are remunerated at a rate below the market rate, as is generally the case, achieving the desired interest rate target entails that the central bank supply reserves as demanded by the system. In the case where reserves are remunerated at the market rate, they become a close substitute for other short-term liquid assets and the amount of reserves in the system is a choice of the central bank. In either case, the interest rate can be set quite independently of the amount of reserves in the system and changes in the stance of policy need not involve any change in this amount.

Which means that banks normally desire to hold a certain quantity of reserves as per their expectations of the claims that will be made on it via the daily clearing house.

Further, unless the central bank pays a market return (short-term interest rate target) on overnight reserves, it has to be ready to supply whatever reserves are required to match the desired demand by banks or else lose control of the target rate.

One example that MMT provides is a version of this and also serves to demonstrate how budget deficits put downward pressure on interest rates, is that when a government is running a deficit, it involves a net add to bank reserves (after all the transactions which arise from the deficit spending are conducted by consumers/firms etc). If the resulting quantity of reserves is in excess of the quantity that the banks perceive will satisfy their payments needs (plus reserve requirements if relevant), then the banks will try to loan those reserves out in the interbank market.

But as noted above, the banks together can only shuffle the excess reserves. The act of each individual bank trying to pass on the excess reserves that it holds (noting some banks might still have reserve deficiencies even when the overall system is in excess because of the nuances of the pattern of cheques drawn and presented) manifests as an excess supply of funds which drives the overnight interest rate down. It will fall to zero if there is no central bank return on reserves paid or to the support rate (the return on reserves offered by the central bank). But the interbank competition under these circumstances compromises the central bank’s target interest rate.

Finally, when the central bank pays a return on reserves held with it equivalent to the target rate of interest then the maintenance of that target is independent of the quantity of reserves in the system. That situation describes the current state in many nations.

The upshot is (according to the BIS paper) that:

The same amount of reserves can coexist with very different levels of interest rates; conversely, the same interest rate can coexist with different amounts of reserves. There is thus no direct link between monetary policy and the level of reserves, and hence no causal relationship from reserves to bank lending …

The absence of a link between reserves and bank lending implies that the money multiplier is an uninformative construct.

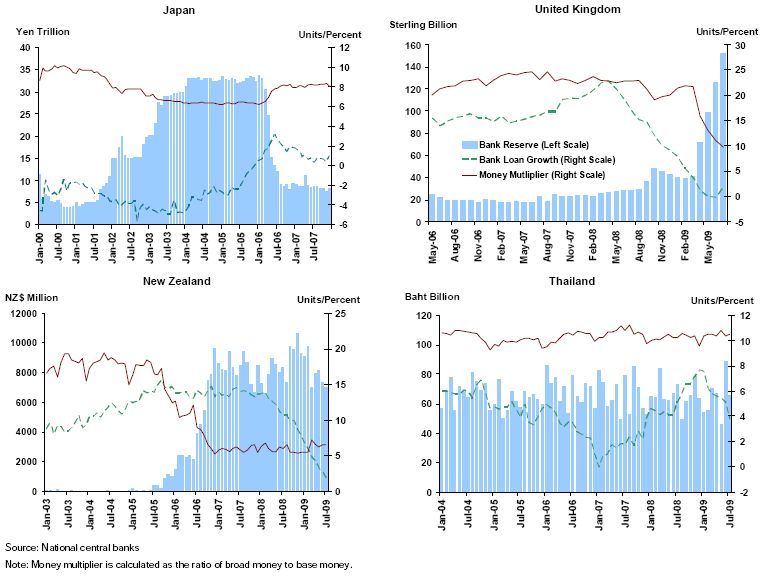

To reinforce this conceptual conclusion the BIS paper offer the following graph (their Figure 1 Money Multiplier and Credit Growth). The red-line is an expression of the money multiplier (calculated as the ratio of broad money to base money). They conclude that the “movements in the money multiplier largely reflects changes in reserves, with the latter showing no perceptible link to the dynamics of bank lending”.

They also note that in “the case of Japan and the United Kingdom, the abrupt change in reserves was the result of each central bank’s quantitative easing policy”.

The conclusion is that “the amount of reserves in the banking system, which as noted above, is determined predominantly by exogenous structural factors. When

those factors change, central banks simply accommodate whatever new level of reserves is required by the system”.

So “standard macroeconomic textbooks” still in wide use like Mankiw, Abel and Bernanke, Mishkin and Walsh (2003) which continue to perpetuate the money multiplier myth are deceptive at best and students are being poorly treated by lecturers who use them.

The BIS paper then considers the “alternative …[mainstream] … way of motivating the link between monetary policy and deposits, consider the mechanics of household portfolio rebalancing”:

Here, the presumption is that policy actions that change the opportunity cost of holding deposits act as a catalyst for portfolio rebalancing that affects the level of deposits. This view essentially rests on the conventional interest elasticity of money demand as applied to deposits.

So monetary policy is meant to be able to influence bank lending by reducing the amount of deposits in the system. It is claimed that open market operations change the “relative yields of deposits (money) and other assets” which can discourage deposits.

The BIS paper outlines several reasons why this is unlikely to occur (apart from the obvious fact that bank lending is not restricted by deposits) which you can read about if you are interested.

The basic conclusion is that:

… quantitative constraints on bank lending should be de-emphasized. Even if one accepts the notion that deposits fall in response to tight policy, banks nowadays are able to easily access wholesale money markets to meet their funding liquidity needs … Importantly, since banks are able to create deposits that are the means by which the non-bank private sector achieves final settlement of transactions, the system as a whole can never be short of funds to finance additional loans.

If you think about this statement for a moment you will see that it is impossible for budget deficits to financially crowd out other expenditure. Components of aggregate demand can crowd each other out in a real sense if there is not sufficient real resources available to respond to the increased spending. But that is not the mainstream emphasis.

So we can conclude:

1. Budget deficits now will not cause interest rates to rise and thus damage interest-rate sensitive components of private spending. There is nothing in a valid depiction of banking operations to justify that central mainstream macroeconomics view.

2. The central bank does not (and cannot) control the money supply. So theories of the price level that are based on that presumption (such as the Quantity Theory) are erroneous.

The BIS paper also acknowledges that bank “loans drive deposits rather than the other way around”:

Bank lending … involves the creation of bank deposits that are themselves the means of payment. A bank can issue credit up to a certain multiple of its own capital, which is dictated either by regulation or market discipline. Within this constraint, the growth of bank lending is determined by the demand for and willingness of banks to extend loans. More generally, all that is required for new loans is that banks are able to obtain extra funding in the market. There is no quantitative constraint as such. Confusion sometimes arises when the flow of credit is tied to the stock of savings (wealth) when the appropriate focus should in fact be on the flow.

Again, no crowding out and only capital constraints on bank lending (that is, the asset side of the balance sheet) are binding.

Conclusion

The BIS could hardly be criticised for not have direct experience with central banking – being the central bank of the central bank. The paper reinforces some central tenets of MMT – regarding the role of bank reserves, the way in which budget deficits impact on the cash system and drive down interest rates, the impossibility of financial crowding out and the lack of control central banks have on the expansion of the money supply.

The question that all macroeconomists should ask is why they still teach the mainstream theories which clearly do not apply to the real world banking system.

That is enough for today!

Hi Bill,

the BIS paper is valid also for EMU?

“More generally, all that is required for new loans is that banks are able to obtain extra funding in the market. There is no quantitative constraint as such.”

and

“Further, unless the central bank pays a market return (short-term interest rate target) on overnight reserves, it has to be ready to supply whatever reserves are required to match the desired demand by banks or else lose control of the target rate.”

are valid also for Europe? I mean, ECB (or the agents, for example Bank of Italy) has to supply reserves always to match the demand by banks?

Excellent work Bill. As best as I can tell, today’s post addresses every critique of MMT I have read in the past few days.

You need to get teh Facebook share application on your blog. I have been quoting it for some time now and it would be much easier just to link the entire article. It would also help to get this to spread more!

Great stuff !

You are correct in arguing that credit expansion is not tied to reserves but to capital or as you put it: “Lending is capital — not reserve-constrained.” But neither is lending constrained by ‘deposits’ if you mean the deposits of savers. I assume that ‘deposits,’ as used here, means deposits at the central bank otherwise known as ‘reserves.’ You quote with approval the BIS statement that: “… the emphasis on policy-induced changes in deposits is misplaced. If anything, the process actually works in reverse, with loans driving deposits.” And the BIS goes on to add: “In particular, it is argued that the concept of the money multiplier is flawed and uninformative in terms of analyzing the dynamics of bank lending. Under a fiat money standard and liberalized financial system, there is no exogenous constraint on the supply of credit except through regulatory capital requirements. An adequately capitalized banking system can always fulfill the demand for loans if it wishes to.”

I am left wondering what ‘deposits’ (however you define them) have to do with bank capital. And the suggestion that bank loans increase bank capital leaves me somewhat bewildered. Correct me if I am wrong, but it seems to me that a bank loan constitutes a reduction in a bank’s capital and that this deficit is made good by the fact that a lending bank takes back an IOU or promissory note from the borrower and counts this as an asset or as capital. One asset is exchanged for another and the exchange (leaving aside the interest payments) is pretty much a wash.

In my view, a credit expansion occurs when the bank sells its promissory notes (typically packaged as bonds and labelled as ‘Collateralized Debt Obligations’) and counts these borrowings or debts as assets or capital. It is this wonderful alchemical transformation of a liability (lead) into an asset or capital (gold) which created the sea of liquidity floating the ill-fated housing boom. What occurs here is that the original loan — on the house, car, home appliance, etc. — is is doubled. Twice the credit is generated from the same asset. Or put the other way, the house, car, etc. collateralized both the loan to the house buyer or car buyer and a further loan (of ‘capital’) to the bank which made the primary loan.

You maintain that: “More generally, all that is required for new loans is that banks are able to obtain extra funding in the market. There is no quantitative constraint as such.”

Absolutely the case. Derivatives proved the means, and we witnessed the consequences when, “There is no quantitative constraint as such.”

Does the MMT have an answer for why in the UK, the velocity of broad money (Nominal GDP over M4 ex OFCs, to be precise) started rising for the first time in a decade, in exactly the same quarter that the QE program started? Was this just coincidence?

Here is a graph of both – M4 ex OFCs is the Bank of England’s preferred measure of broad money, FYI:

http://timetric.com/overlay/PF4-iys7SjivQ5-D-prL5w,XFJ9Cfs1R8CefQHUj534wQ/

“Intrinsically, a sovereign government issues the currency so it is never revenue constrained.”

As a new, interested subscriber I want to ask you about this point. I understand the notion of a sovereign, fiat currency. But it appears that any sovereign government *may be* revenue constrained if imports form a meaningful part of domestic expenditure. If your sovereign currency is exchangeable, then whether or not the issuers of other sovereign currencies believe you can pay for everything you consume will determine its exchange rate. In an extreme case, you won’t be able to purchase what you want from other countries since they can devalue your currency as fast as you print it.

The result is essentially that foreseen by Malthus — that the consumption of every country may, in principle, be constrained by the size of its population, the limits of its natural resources, and extent of its technological development. This is not a refutation specifically of MMT, but of any economic theory that posits unlimited growth of social welfare. And of course, it does not bear upon the more important question of how existing resources are distributed.

What do you think? Have you read Malthus’ Principles of Political Economy with a View Toward Considering their Practical Application (2nd ed. 1836)? (No reason you would, it’s quite obscure.) Still, perusing PPE, Part 2 (especially) might start some further wheels turning in your critique of conventional economic theory, and change your view of Malthus (assuming you have one). Good luck, in any case.

On the topic of textbooks, I’m an Irish economics student who will be starting a Master’s in September and I’m wondering if you could say a bit about the scope of the textbook that you are writing with L. Randall Wray and when it might be available? I asked Randall when he was here but there were a lot of questions and the discussion didn’t get round to it.

A simple explanation of how deficit spending results in more reserves in the system would be great, if you get the time. I get the general concept: net deficit spending is a vertical transaction and shows up as an increase in reserves, but what are the intermediate steps, as per our actual institutional arrangements (this is not stealth version of a complaint confusing operational and political constraints – I just want to understand the details a bit better).

Thanks.

I agree with Bill that loans create deposits and that additional reserves do not encourage banks to lend. But it strikes me that central banks COULD CONTROL commercial banks with the reserve rule if they chose to. Of course central banks would have to let interest rates rise when commercial banks were up against their reserve limit and irrational exuberance reared its ugly head.

So why don’t central bankers do this? It wouldn’t be a bad way of choking off excess demand when needed. I suspect central bankers don’t adopt the latter policy because they like to think they are in charge and that their favourite weapon, interest rates, actually works. It wouldn’t do their egos any good if it appeared they were being pushed around by market forces and/or that their favourite weapon was ineffective.

can we help those who will not help themselves?

http://www.calpers.ca.gov/index.jsp?bc=/about/press/pr-2011/july/public-pension-funds.xml

This post is destined to become a classic, Bill. Great work.

“2. The central bank does not (and cannot) control the money supply. So theories of the price level that are based on that presumption (such as the Quantity Theory) are erroneous.”

Most of the time, I suggest dumping the word “money” because you are going to run into definition problems.

I think scott sumner would say the central bank can control the money supply because he defines it as the monetary base (currency plus central bank reserves).

Here is what needs to be answered.

1) Can the central bank increase the amount of currency?

2) Can the central bank increase the amount of central bank reserves?

3) Can the central bank increase the amount of demand deposits?

“The commercial banks are required to keep reserve accounts at the central bank. These reserves are liabilities of the central bank and function to ensure the payments (or settlements) system functions smoothly. That system relates to the millions of transactions that occur daily between banks as cheques are tendered by citizens and firms and more. Without a coherent system of reserves, banks could easily find themselves unable to fund another bank’s demands relating to cheques drawn on customer accounts for example.”

So is it accurate to say central bank reserves are liabilities of the central bank and assets for the commercial banks that circulate as a type of medium of exchange within the banking system covered by the central bank (its member banks)?

“Banks may trade reserves between themselves on a commercial basis but in doing so cannot increase or reduce the volume of reserves in the system. Only government-non-government transactions (which in MMT are termed vertical transactions) can change the net reserve position.”

But, what about changes to the reserve requirement?

“Bank loans create deposits not the other way around. These loans are made independent of their reserve positions. Adequately capitalised banks lend to any credit-worthy customers.

At the individual bank level, certainly the “price of reserves” will play some role in the credit department’s decision to loan funds. But the reserve position per se will not matter. So as long as the margin between the return on the loan and the rate they would have to borrow from the central bank through the discount window (the worst case scenario) is sufficient, the bank will lend.

So the idea that reserve balances are required initially to “finance” bank balance sheet expansion via rising excess reserves does not capture the way the banking system operates. A bank’s ability to expand its balance sheet is not constrained by the quantity of reserves it holds or any fractional reserve requirements. The bank expands its balance sheet by lending. Loans create deposits which are then backed by reserves after the fact. The process of extending loans (credit) which creates new bank liabilities is unrelated to the reserve position of the bank.”

I like to think of it this way.

All new medium of exchange has to be the demand deposit(s) from a loan/bond/IOU (making it debt). The demand deposit gets a reserve requirement, and the loan/bond/IOU gets a capital requirement. The bank capital can come from someone who decides to save in the medium of exchange of demand deposits (or currency).

Ralph Musgrave said: “I agree with Bill that loans create deposits and that additional reserves do not encourage banks to lend. But it strikes me that central banks COULD CONTROL commercial banks with the reserve rule if they chose to. Of course central banks would have to let interest rates rise when commercial banks were up against their reserve limit and irrational exuberance reared its ugly head.

So why don’t central bankers do this?”

If I’m reading that correctly, you mean raise the reserve requirement so the commercial banks have to hold more required reserves. If so, I believe that would lower the commercial banks’ profitability.

Now you wouldn’t want banker bonuses to go down. They might become “unmotivated” and stop producing debt. That means the sun might not rise the next day. ~sarcasm intended~

Plus, jamie dimon might have to ask ben bernanke if that was too much regulation at the next fed news conference just to prove how connected he is.

RK, I’ll try based on what I have been told here (simple version).

If the gov’t gives you a tax cut, they markup your demand deposit account (checking account). They also markup your bank’s reserve account 1 to 1. That reserve account markup (excess reserves now) would probably drive the fed funds rate to zero(0). To keep that from happening, the gov’t can sell a bond. If a person buys the bond, their demand deposit account is marked down by the same amount, and the bank’s reserve account is marked down 1 to 1. The reserves transactions cancel out. You get a demand deposit, and the other person gets a bond (savings vehicle).

Fed up, Re you second last comment above, I wasn’t suggesting that central banks should RAISE reserve requirements. I suggested they could leave reserves at a their existing level during a boom, and that would force interest rates up. That is, central banks could control demand by controlling reserves rather than deliberately adjust interest rates. I think China’s central bank does this. But in the West it seems not to be common practice.

You asked whether “central bank reserves are liabilities of the central bank”. My answer is that they are NOMINALLY a liability. E.g. in the UK, £10 notes say “I promise to pay the bearer the sum of ten pounds” (in gold presumably, ho ho). But in reality, reserves (i.e. monetary base), are to use Warren Mosler’s phraseology, like points dished out in a tennis match. They are just units distributed in order to enable us to play a game called “economic activity”.

As to whether reserves are an asset for commercial banks, it strikes me they may be and may not. E.g. if the central bank is doing some QE and I sell them my holding of government debt, I then become the owner of some monetary base, or “reserve”. My commercial bank is just an intermediary between me and the central bank. On the other hand a commercial bank can be a holder of monetary base in its own right.

“But it strikes me that central banks COULD CONTROL commercial banks with the reserve rule if they chose to. ”

The central bank simply isn’t required. It’s just an accounting convenience. It’s an intermediation between the private banks because they either don’t trust each others deposits or there is regulation in place requiring the clearing to go through the centre.

So if Bank A owes Bank B when all the cheques have gone through then Bank B could just charge Bank A directly for running an overdraft.

If capital constraints are in place and enforceable this overdraft would become part of that amount. The fiat power of government then manifests as the ability to instruct the banks to add and remove amounts from any account in their systems.

So yes you can control the system with reserves – 100% reserve being the full manifestation of that control, but ISTM that you can only control an individual bank with capital requirements.

Ned, you left a few things hanging there and none of the guns have bought in, so I’ll chuck in my 2 cents:

You said:

“I am left wondering what ‘deposits’ (however you define them) have to do with bank capital.”

As I understand things Ned, deposits have nothing to do with capital. Capital is, at its simplest, the equity of the shareholders, common stock. After that, there are other “lesser” measures of capital (like sub-ordinated debt, preference shares etc) that are called up in the Tier 1 and Tier 2 rules of the Basel Accord.

“And the suggestion that bank loans increase bank capital leaves me somewhat bewildered.”

I don’t think Bill actually said that. I think you might’ve confused “capital” with “assets” (as seems the case from your following remarks):

“Correct me if I am wrong, but it seems to me that a bank loan constitutes a reduction in a bank’s capital and that this deficit is made good by the fact that a lending bank takes back an IOU or promissory note from the borrower and counts this as an asset or as capital.”

Loans are certainly booked as assets from the bank’s perspective, but assets are not capital. I think this is a common misunderstanding. I’m always amused when economic journalists, seeking to apologise for the profits of our big banks in Australia, tell us the banks are only making 2% on their assets (our loans, our collateral !)

For the record, the Basel Accord allows banks to leverage their capital base by a factor of around 15 times. That’s what I would call “credit expansion”. Banks create money (“bank money”, as opposed to “base money”) pretty much out of thin air. But they scratch it when the loans are paid off.

I think your comments about derivatives would be better addressed from the perspective of a lack of regulatory restraint rather any quantitative restraint.

John

Am I right in thinking that the part of banks capital represents the difference between reserves held at the central bank (assets) and deposits (liabilities) which i would imagine, more often than not, means reduced capital?

“I am left wondering what ‘deposits’ (however you define them) have to do with bank capital.”

From JKH at:

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=15038

“Fed Up,

I assumed 10 in central bank reserves as a corrective modification to your starting balance sheet, as I already explained. It’s got nothing to do with a reserve “requirement”.

Let’s start over.

Suppose you create a new bank.

You issue 10 in capital (shares).

New investors pay for their shares that by writing cheques on their deposits at other banks.

That brings central bank reserves into your bank (as settlement for the cheques). The role of reserves in this case is their use as settlement balances, not because of a “reserve requirement”.

Your starting balance sheet is:

Assets:

10 central bank reserves

Capital:

10 capital

At that point, you have no loans and no deposits.”

I believe the same scenario applies to an existing bank selling new shares. What I believe happens is someone decides to save in the medium of exchange of demand deposits. That someone then decides to purchase a financial asset that is new bank stock. That new bank stock is bank capital (see balance sheet transactions above).

Firstly, while it was published by the BIS it should be noted that there is a disclaimer stating that the article does not necessarily represent the views of the BIS. Given that many references are to leading endogenous money proponents such as Wray it appears to more of a rehash than a groundbreaking statement from the BIS.

There is one thing I have not seen satisfactorily answers regarding endogenous money theory. The theory is that banks make loans first and later seek reserves. So it is not saying that banks are not reserve constrained merely the order they do things and that they seek reserves last of all. If reserves cannot be sought through interbank borrowing lending then the central banks will lend the money – in fact they have to ensure stability. Therefore as banks must ensure they have required reserves (either voluntary or regulated depending on the country) by their reporting period and reporting periods are frequent, then the endogenous theory of money would show that in periods of credit expansion, the monetary base (I.e. Reserves) would be pulled up with little lag. There must be a pull effect.

But the empirical evidence does not show this – during the credit explosion for the early 2000s the average annual growth in the monetary base was the lowest since WW2. How is this possible with endogenous money – surely this should be the smoking gun that proves the theory – but it doesn’t.

What seems to be a more logical explanation, is that the system is reserve constrained but in a voluntary system a combination f increased propensity to borrow by individuals and businesses combined with an opening of risk appetite from banks, leads them to reduce their voluntary reserve and increase the lending capacity in the system to satisfy demand. This would allow a credit expansion to occur without the need for increased reserves – a drop in reserves from 10% to 5% allows a 100% expansion in credit with no new reserves.

Not only is this what the empirical evidence fits but also takes into account the FED is not completely submissive when faced with requests for funds and that banks employ large treasury departments to manage liquidity and ensure they do not have to go cap in hand to the FED for injections of reserves for long periods or outside of ordinary short term FED facilities that are primarily used to balance liquidity needs based on in and outflows from government accounts.