I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

The US is living below its "means"

The US press was awash with claims over the weekend that the US was “living beyond” its “means” and that “will not be viable for a whole lot longer”. One senior US central banker claimed that the way to resolve the sluggish growth was to increase interest rates to ensure people would save. Funny, the same person also wants fiscal policy to contract. Another fiscal contraction expansion zealot. Pity it only kills growth. Another commentator – chose, lazily – to be the mouthpiece for the conservative lobby and wrote a book review that focused on the scary and exploding public debt levels. Apparently, this public debt tells us that the US is living beyond its means. Well, when I look at the data I see around 16 per cent of available labour idle in the US and capacity utilisation rates that are still very low. That tells me that there is a lot of “means” available to be called into production to generate incomes and prosperity. A national government doesn’t really have any “means”. It needs to spend to get hold off the means (production resources). Given the idle labour and low capacity utilisation rates the government in the US is clearly not spending enough. The US is currently living well below its means. But the US government can always buy any “means” that are available for sale in US dollars and if there is insufficient demand for these resources emanating from the non-government sector then the US government can bring those idle “means” into productive use any time it chooses.

Spending equals income. Someone has to spend for incomes to exist. For incomes to grow there has to be growth in spending. There are three sources of spending growth in a macroeconomy – the external sector (if net exports are positive); the private domestic sector; and the government sector (if the budget is in deficit).

That is indisputable. Economic growth is defined in terms of production and production only occurs if there are goods and services being purchased. Firms do not produce to hold inventory. Firms may invest in response to their guesses about future sales. These guesses will be heavily influenced by current consumer actions.

So when you get commentators and high-level monetary officials arguing that growth comes from not spending you have to ask why anyone would listen to their views and why they are paid to express them. I don’t mind bloggers who do it for free saying what they like but when highly-paid and highly-visible express views that are not grounded in any economic theory that is comprehensible but nonetheless seek to influence the policy debate then I get angry.

First up today is the Bloomberg report (May 29, 2011) – Hoenig Seeks Higher U.S. Interest Rates to Boost Saving, Avoid New Bubbles – which suggests that in the wake of a very subdued recovery accompanying very little credit growth to speak off and persistently high unemployment, monetary policy should tighten.

Why? To encourage personal saving (that is, anti-spending).

The boss of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Thomas Hoenig told CNN that:

… the U.S. needs to raise interest rates to encourage individuals to save and avoid future asset bubbles.

In the same interview he said:

If we want to be a great nation, continue to be a great nation, then we do have to address our fiscal challenges …

Which when you put the two statements together (even without examining the logic) tells us he wants the US economy to go back into recession.

He thinks that US monetary policy is too “slack” and that there is a “very easy credit environment” which “encourages consumers to spend at a time when the U.S. needs higher savings rates to ensure long-term prosperity”.

The US Bureau of Economic Analysis report that in April 2011 the personal saving as a percent of disposable income was 4.9 per cent and this is up on the low points prior to the crisis (it reached 0.8 per cent in 2005).

Demand for credit is low as is growth in consumer spending and private investment. Net exports are also draining economic growth. It is clear that if you also cut public net spending (“address our fiscal challenges”) and “encourage” private saving (with private investment growth stalled) then you will see production decline and unemployment will rise.

Further, US households are still carrying large debt burdens (see analysis next) and are being cautious at present although the severe and entrenched unemployment is not conducive to strong credit growth anyway.

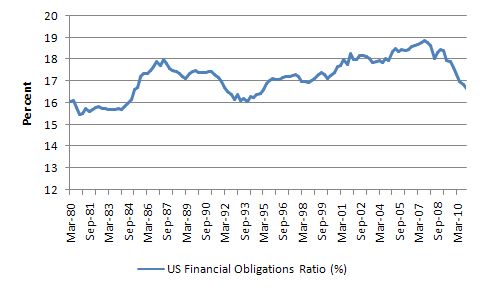

The following graph is taken from data provided by the US Federal Reserve and shows its Financial Obligations Ratio (FOR) (quarterly from March 1980 to December 2010). The US Federal Reserve describe the FOR as an “estimate of the ratio of debt payments to disposable personal income” where “Debt payments consist of the estimated required payments on outstanding mortgage and consumer debt” plus “automobile lease payments, rental payments on tenant-occupied property, homeowners’ insurance, and property tax payments”.

It is their most comprehensive measure of the burden of personal debt in the US. As household saving has increased a little since it hit rock bottom just before the crisis the FOR has fallen. The lower interest rate environment is also helping.

But the point that is lost in Hoenig’s call is that the fastest way for households overall to save is to grow the economy. Household saving is a positive function of national income which means that the stronger is the growth in income the stronger (other things equal) the growth in saving.

Like all these ratios that are income sensitive (saving ratio, budget deficit to GDP, public debt ratio) the way to reduce them is to push growth. Trying to engineer an increase in personal saving at this time while also reducing the budget deficit is the best way to reduce the saving ratio.

The other point is that with net exports draining demand (and growth) in the US, the modest rise in the personal saving ratio since the crisis (which is allowing some highly exposed households to reduce their balance sheet risk – that is, pay down debts) was only possible because the budget deficit rose. The budget deficit has been supporting demand (spending) and hence growth in the US economy.

You cannot have overall saving in the private domestic sector and an external deficit and economic growth without a rising budget deficit. That is not a personal opinion but rather a fact that comes from understanding the way in which the macroeconomy works and the relationships between the three spending sectors noted above.

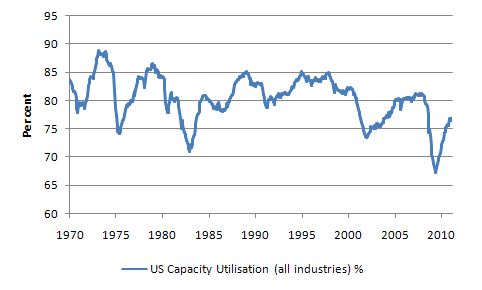

The glaring issue that is facing the US economy at present can be summarised by this graph which shows the Industrial Production and Capacity Utilization – G.17 series available from the US Federal Reserve (monthly data from January 1970 to April 2011).

The utilisation rates – which tells you how intensively productive capacity is being used – fell to its lowest level in more than 40 years during the crisis. It is still hovering at relatively low levels and there is plenty of productive slack available. This graph tells us why there is high and entrenched unemployment in the US for the first time in decades. Long-term unemployment is now a US problem whereas in previous recessions the US has rebounded more quickly.

This is the issue that should be “front and centre”!

If the US government followed Hoenig’s line, growth would collapse, personal saving would fall overall (as unemployment and lost income rose) and the budget deficit would rise (as the automatic stabilisers drove increased spending with falling revenue).

It is a good thing that he is retiring this year from his central bank position. He will probably turn up at the Peter G. Peterson foundation.

Which brings me to the second abomination of the weekend.

Saturday’s New York Times (May 28, 2011) carried an article – U.S. Has Binged. Soon It’ll Be Time to Pay the Tab – by one Gretchen Morgenson, who appears to have started life as a women’s fashion writer and now proclaims to know something about macroeconomics.

The NYT could have saved the ink and paper.

Her article is really an advertisement for a book written by some characters from the Peterson Institute for International Economics

Question: How many PGP institutes/foundations are there? If anyone has done some analysis of the variety of propaganda machines that enjoy his financial support I would be interested in the list.

I loved the preface in the Peterson “book” (link later) which claimed that:

The Institute undertook this project at the request of the Peter G. Peterson Foundatino, which is a completely separate entity. The Foundation focuses much of its attention on the fiscal prospects and problems of the United States, and it asked the Institute to imbed those national issues in the global context to assess how that broader perspective might affect the outlook and especially the need for early policy action by the United States.

Left toe to right toe, wiggle! Okay!

Gretchen Morgenson says that:

… at least people are talking openly about our nation’s growing debt load. This $14.3 trillion issue is front and center – exactly where it should be.

Milton Friedman once said that if the US government stopped publishing Balance of Payments data then the issue would go away. Same goes for the public debt data. Who would know or care about it if there wasn’t a relentless stream of “debt clocks” (which I prefer to call private wealth accumulation clocks) based on official debt data? Answer: no-one? Why? Because the public debt and its relation to GDP is largely an irrelevant statistic the doesn’t tell us much of interest.

But Gretchen Morgenson thinks otherwise and decides to promote the Peterson book – The Global Outlook for Government Debt over the Next 25 Years: Implications for the Economy and Public Policy. It is in fact a very short book – 94 pages and only 49 of those are text. Gretchen Morgenson calls it a “thoughtful new paper”. It could have been about one paragraph or perhaps one sentence “government debt is about to explode, we hate it, we want government spending cut unless it benefits the elites”. The End.

The “institute” has the audacity to be charging $U10.95 for it although it has recently been discounted to $US8.76. But you can download what they claim is the preview version for free – which is one of those times when a zero price is excessive.

She quotes from the book:

That government debt will grow to dangerous and unsustainable levels in most advanced and many emerging economies over the next 25 years – if there are no changes in current tax rates or government benefit programs in retirement and health care – is virtually beyond dispute.

That quote is from the preface. Unfortunately I read on!

The “book” acknowledges that “in the major advanced economies, investors have bought up the new debt avidly, keeping the rates of interest on government bonds near 50-year lows”, yet Gretchen Morgenson claims that markets need to be reassured by a program of fiscal retrenchment being announced although not necessarily implemented immediately.

Markets are buying what debt is issued and queing up for it. They would scramble over each other to get it if the bond tenders were thrown out on “sale table” like sale items in shops are at different times of the year. The markets are scared argument carries no weight.

The “book” notes that “investors have been much less keen to buy the rising debts of some peripheral members of the euro area” which is clearly true and tells us that bond markets can tell the difference between a monetary system where the national government (and bond issuer) carries no solvency risk (for example, the US) and a monetary system like the Euro, where the national governments are effectively issuing debt in a foreign currency and can easily default on financial grounds.

That is obvious and tells us two things: (a) those government that face no solvency risk are providing the private sector with a risk-free haven to store their saving (the bonds) while at the same time guaranteeing the private bond investors a safe income for the time over which they hold the bonds; and (b) the national governments in the Eurozone should exit and restore their currency sovereignty and not be held to ransom by private bond markets.

In any case, the issuance of government bonds for a sovereign nation (that is, a government that issues its own currency and floats it on foreign exchange markets) is entirely voluntary and should only be the result of a thorough analysis as to whether providing corporate-style welfare (selling risk free income streams to the wealthy) is advancing public purpose. My view is that it does not advance broad concepts of social welfare and should be discontinued.

Please read my blogs – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3 – for more discussion on this point.

Gretchen Morgenson quotes the author of “book” who claims the “simultaneous buildup of very large public deficits and debt positions in virtually all of the advanced high-income countries”:

… is a new element at work in the global economy … It is unique in peacetime for so many countries to have so much debt …

Whether this is “peacetime” is questionable (given the “war on terror and everything else”) but it is also the first time in 80 years that private spending has collapsed so comprehensively across the globe and the entrenched nature of this collapse is being ensured by the excessively moderate fiscal support that governments are providing their ailing economies.

If governments around the world had have quickly ensured aggregate demand was maintained the decline would have been much shallower and shorter and the public debt ratios would have not been nearly as high as they are now – not that the rise in the debt ratios per se is where we should be focusing our attention.

As a matter of fact, I did a string search on the “book” for the word “unemployment”. Frequency: 0. Conclusion: the “book” focuses on a non-issue as does Gretchen Morgenson.

She quotes the authors who claim that the fiscal austerity programs in Europe are reducing the severity of the long-run debt issue there relative to the US which is dragging its chain on cutting “long-run pensions” and other “spending cuts and tax increases”. This is presented to her readers without any scrutiny at all.

There is no mention that budget deficits are actually rising in Europe in the worst hit countries as they slash welfare and worker entitlements because they are also undermining growth and losing revenue. Britain is now following suit. The conservatives would see the same path being followed in the US.

They are in denial of the reality that you spend your way to growth. Fiscal contraction expansion is a nasty ideological lie. They should stop perpetuating it. Journalists like Gretchen Morgenson who clearly do not understand monetary economics and macroeconomics in general should stop acting as their mouthpieces.

She finishes the article with the standard beat up of the US health system. She asks us to “sit down” because the numbers are so bad. My view is that more Americans should stand up, put some running shoes on or get on a bike and lose some weight and lower the real burden on the health system in that way.

There is no question that the US government can “afford” to maintain a first-class health care system. Gretchen Morgenson fails to understand what a “cost” is.

She says:

Under a best-case outlook, according to the authors, the nation’s net federal debt will rise to 155 percent of gross domestic product in 2035, more than double the current levels. (Net debt is defined as the government’s financial liabilities minus its financial assets.)

At which point I yawned.

So what? That is a lot of private wealth being stored in a risk free asset with a guaranteed income flow that has been voluntarily purchased by non-government wealth holders.

Oh to be so fortunate!

What the hell does she think will happen? Quoting a staggering array of ratios and numbers (which she does) means nothing – other than mislead the misinformed (which includes herself).

What does she think will happen? Silence.

Why is a rising debt ratio a problem? Silence.

She finishes with what she calls “straight talk on a vital topic” by quoting the Peterson rag:

There may never be a single defining moment of crisis … but rather a drift into ever-higher inflation and interest rates, ever-lower growth or deeper recession, and eventually hyperinflation along with rapid currency depreciation. Most economists would view such a prospect as a progressive strangulation of a nation’s well-being.

As usual, the standard neo-liberal scare scenarios:

Higher interest rates – please read my blog – Will we really pay higher interest rates? – for more discussion on this point.

Higher taxes – please read my blog – Will we really pay higher taxes? – for more discussion on this point.

Hyperinflation – please read my blogs – Modern monetary theory and inflation – Part 1 and Modern monetary theory and inflation – Part 2 and Zimbabwe for hyperventilators 101 – for more discussion on this point.

Rapid currency depreciation – please read my blog – Modern monetary theory in an open economy – for more discussion on this point.

Unsustainable fiscal position – please read my blogs – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 1 – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 2 – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 3 – for more discussion on this point.

Deeper recession – please read my blogs – Fiscal austerity – the newest fallacy of composition and Back to basics – aggregate demand drives output and Beyond austerity – for more discussion on this point.

Deficits are bad – please read my blog – The full employment budget deficit condition – for more discussion on this point.

Conclusion

Gretchen Morgenson claims that she hopes the US leaders “understand that living beyond our means will not be viable for a whole lot longer”. Well she should learn what these “means” are.

With around 16 per cent of available labour idle in the US and capacity utilisation rates still very low there is a lot of “means” available to be called into production to generate incomes and prosperity.

A national government doesn’t really have any “means”. It needs to spend to get hold off the means (production resources). Given the idle labour and low capacity utilisation rates the government in the US is clearly not spending enough. The US is currently living well below its means.

But the US government can always buy any “means” that are available for sale in US dollars and if there is insufficient demand for these resources emanating from the non-government sector then the US government can bring those idle “means” into productive use any time it chooses.

The national level of unemployment is largely a matter of choice of the national government.

That is enough for today!

]]>

I would have thought the best way to challenge the ‘cut spending’ lobby is to require them to wheel out pledges from the private sector to replace the spending that they are proposing to eliminate from the government sector. A bit like a charity event if you like.

I see nobody from the private sector saying “I will put a million dollars into the economy if the government cuts a million dollars”. All I see is “please eliminate my competition and reduce my labour costs so I can extract more profit”.

Why aren’t we requiring these mystical private sector entities to put their money where their mouth(piece) is?

Dear Bill

The US economy is running below its capacity, for sure, but the Americans are collectively indeed living above their means because they are spending more than they are producing. Any country that runs persistent trade deficits, as the US has been doing, is living beyond its means. It may be able to do that for a long time, but not forever.

I keep reading that the Chinese save about 40% of their income. Yet China is growing at a very fast rate. How do they do it? Every Asian tiger has had extremely high savings rates.

The relation between household savings and investment is mysterious. On the one hand, household savings reduce demand for the goods and services of firms, thereby making firms less inclined to invest, but on the other hand, high investment requires lower consumption, that is, more household savings.

It is easy to conceptualize the relation between savings and investment for a single household. For instance, if Robinson Crusoe lives by fishing and if he wants to increase his productivity, then he has to invest some time to building fishing equipment, which means either yo eat less fish for a while or else to enjoy less leisure. In an anonymous market it is much harder to conceptualize.

Regards. James

“the issuance of government bonds for a sovereign nation … is entirely voluntary”

Has anybody ever questioned why they issue tradeable bonds? I would have thought that if the idea was to guarantee that money was put ‘out of use’ for a period of time they should be offering term deposits with the central bank with no early withdrawal option.

Neil, isn’t it simply because they believe it funds government expenditure?

Trade deficits matter, indeed cut oil imports on USA and you will see fast how it’s living beyond its means. USA is highly inefficient and dissipates way more energy than it creates. Yeah sure, foreigners can exchange USD for goods which they will have to use at some point in USA, but that’s not the real deal, the real deal is that at some point they will realize they don’t have any real place where to spend them as USA loses competitive advantage on the different ‘industries’ (including finance, due to the capital account position the status quo is maintained in big part).

The problem is as long as this continues the capital structure of the nation is distorted and dependence on external inputs compared to exports increases. You see where this leads eventually: a collapse of real economy or war and imperialism just to keep the level of external goods consumption. The longer the USD is the reserve currency the worse for USA and for the rest of the world, because the demand shock will be bigger when adjusted and the pain for the population higher. At some point people outside of USA will drain more of these resources for their-shelves, and then there will be trouble with an high trade account deficit.

Add to that, that to archive full capacity utilization, you will need MORE imports, which means higher demand for goods and higher inflation, while having stagnant wages and a bigger, even, trade deficit.

Huge investment is needed for replacement of imports and lower consumption of energy. A lower dollar would help, but then you have costs inflation rise and this means trouble. Less consumption and growth in jobs that need less imports is what is needed.

We are getting there, the era of degrowth is coming soon and is unavoidable, and increasing trade deficits is not of any help to fix the capital structure.

James,

But what if instead of fishing, Robbie just would want to live off of picked coconuts? 😉

“Any country that runs persistent trade deficits”: There are many US domestic producers and laborers that together would like to put an end to this too believe me, but meanwhile they are unwilling to lower their standard of living to compete against the pegged exchange rates…. so-called “free trade”.

Look at the graph that Bill posted above on the long term US capacity utilization, that is in an overall 40 year downtrend as we outsource production to the external sector, and our US morons in charge of fiscal policy make no fiscal adjustments in response to this…. We need tariffs and/or tax cuts and/or direct govt job guarantees to counteract the real effects of these chaotic import policies.

Resp,

Mr. Schipper;

Foreign banks, including foreign central banks, accumulate dollar reserves for self-interested reasons – see James K. Galbraith’s “The Predator State” for full details. The U.S. trade deficit stems largely from this. For an excellent primer on MMT, please visit moslereconomics.com and download the free pdf version of “The Seven Deadly Innocent Frauds.”

You are obviously a thoughtful guy. We need more people like you to get on board.

Cheers

James Schipper:

Given that we live in a globalized world and capital moves to the highest return, even if we did accept that savings drives investment why would we expect that US consumer savings would drive investment in the US?

Nothing necessarily keeps US savings from being invested in the US.

I think another way to look at this is that consumption is also a function of relative wage rates and that lower relative consumption (e.g., higher “savings” rates) equate to lower relative wages.

So you might expect investment to be driven to those areas with lower wage rates, which would have lower relative consumption, reflected as higher savings rates. Particularly in countries with relatively small middle classes (e.g., China).

Neil:

Isn’t a term deposit with the central bank with no early withdrawal option exactly what a government bond is? I think the point is to keep the money out of the consumption stream and convert it into a tradeable (leveragable) financial asset.

I think the whole savings/investment dichotomy is a neoliberal canard. Isn’t it all based on the loanable funds fallacy? Doesn’t it depend on the notion that money has to be saved up before it can be fractionally lent out? Loans create deposits. Money is mainly borrowed by people seeking to invest. Private savings are leakages from the cycle of payments that need to be made up for by government spending. Otherwise, growth will decline, investment will be unprofitable and the economy slide toward recession.

The point of today’s blog is that the U.S. could and would be much more prosperous if our leaders understood how the economy actually works. Instead, they are all singing from the Peterson hymnal about impending debt-doom. The trade deficit just shows that people and countries all over the world are happy to accumulate dollar-dnomiated financial assets while we Americans accumulate automobiles, furniture, appliances, etc. that we don’t collectively have to pay for. We could consume all of this, and much, much more, if the idle capacity of the U.S. economy was employed. And since the private sector won’t employ it, the public sector should.

Warren Mosler for President.

James Galbraith for Treasury Secretary.

Randall Wray for Labor Secretary.

Bill Black for Attorney General (while we’re at it).

And Bill Mitchell to head the (reformed) IMF or the (reformed) World Bank.

Or both.

I think it’s important to note that health care in the US is not so much more expensive than it is in other industrialized countries because Americans are so much more unhealthy than their foreign counterparts. And it’s not as if real health care costs are that much greater either, medical equipment, medicine and doctor and nurse wages pretty much cost the same here as in Europe. Rather, it’s due almost entirely to the perverse system of financing health care the US uses. Private insurance companies appear to have the same effect in the health care market that commodities speculators do in the commodities markets, but since insurance companies are largely shielded from directly competing with each other thanks to various laws and regulations that grant them regional monopolies, unlike with commodities speculation, we don’t see price volatility so much as high price inflation.

While only peripherally related, I thought some might find the memoir of Peter G Peterson of some interest:

Blackstone’s Peterson Flopped at MIT, Rose on Dumb Luck: Books

Review by James Pressley – June 11, 2009 19:00 EDT

http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=newsarchive&sid=aqIjW8VZrFFg

While he is no academician, he surely has some important political friends/associates.

“The US is living below its “means””

With debt (private or public) or without?

“Spending equals income. Someone has to spend for incomes to exist. For incomes to grow there has to be growth in spending. There are three sources of spending growth in a macroeconomy – the external sector (if net exports are positive); the private domestic sector; and the government sector (if the budget is in deficit).”

“Spending equals income.”

But, does spending in the present equal income in the present?

“There are three sources of spending growth in a macroeconomy – the external sector (if net exports are positive); the private domestic sector; and the government sector (if the budget is in deficit).”

But can debt (whether private or public) “infect” any of those three or better yet all 3 so that there are time differences between spending and income (earning)?

“You cannot have overall saving in the private domestic sector and an external deficit and economic growth without a rising budget deficit.”

I disagree with that. The currency printing entity can run a deficit of currency with no bond attached.

savings of the lower and middle class plus savings of the rich = dissavings of the currency printing entity with currency and no bond attached plus the balanced budget(s) of the various levels of gov’t. That would give the best chance of productivity gains and other things being evenly distributed between the major economic entities and evenly distributed in time.

“The boss of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Thomas Hoenig told CNN that:

… the U.S. needs to raise interest rates to encourage individuals to save and avoid future asset bubbles.

In the same interview he said:

If we want to be a great nation, continue to be a great nation, then we do have to address our fiscal challenges …

Which when you put the two statements together (even without examining the logic) tells us he wants the US economy to go back into recession.

He thinks that US monetary policy is too “slack” and that there is a “very easy credit environment” which “encourages consumers to spend at a time when the U.S. needs higher savings rates to ensure long-term prosperity”.”

Is it a sign of wealth/income inequality when a higher fed funds rate is needed to prevent asset bubbles from financial asset speculation mostly with debt and another, lower one for other things?

Is there actually a shortage of medium of exchange in the present (as in currency with no bond attached)?

“Gretchen Morgenson says that:

… at least people are talking openly about our nation’s growing debt load. This $14.3 trillion issue is front and center – exactly where it should be.

Milton Friedman once said that if the US government stopped publishing Balance of Payments data then the issue would go away. Same goes for the public debt data. Who would know or care about it if there wasn’t a relentless stream of “debt clocks” (which I prefer to call private wealth accumulation clocks) based on official debt data? Answer: no-one? Why? Because the public debt and its relation to GDP is largely an irrelevant statistic the doesn’t tell us much of interest.”

What about the rollover risk? It seems to me that could be a problem because the gov’t budget is not usually set up to pay back both principal and interest.

James Schipper.

The US trade deficit is 3.6% and reflects it’s trading partners wish to save/hold US currency, compared to capacity underutilisation of 16% 3.6% is much less. Surely the 16% undemployment gap is more serious than the 3.6% trade gap?

Investment decisions depend on ‘confidence’ but this is basically a code word for profitability which depends on demand and income levels, when these are cool/weak investment is lower.

Similarly bank lending depends on this mysterious thing called ‘confidence’ but again this is merely code for good credit risk and depends on the level of economic activity.

You seem to be recommending the Chinese Communist model for the US, I’m intrigued?! 😉

The Asian economies have employed catchup and export lead growth but the there are diminishing returns to this especially when China does it.

Dear Bill,

I am learning a lot as you share your interesting MMT perspective. You say that Greece can’t use QE to foster growth because it doesn’t have its own sovereign currency. What about the sovereign bonds? Is it crazy to use them as a proxy for Greece’s own currency? The government issues new Euro bonds at a discount matching how the market is pricing the Greek bonds. The government then allows China and other buyers of the bonds to purchase assets in Greece using the bonds, or to pay for Greek exports to China. Am I making sense at all?

I donno much about economics, but I do notice the long-term trend in that capacity utilization graph. Any explanation for that? Lazy shiftless workers perhaps? Or lazy shiftless rentiers?

Neil: Has anybody ever questioned why they issue tradeable bonds? Lerner suggested that a function of (tradeable) bonds under functional finance is to decrease private investment (of the hare-brained scheme type, e.g. marginal mining operations), so giving more non-inflationary “room” for government expenditures which would have higher social benefit. Of course this was only at full employment.

Pebird: Isn’t a term deposit with the central bank with no early withdrawal option exactly what a government bond is? No – the tradeability (or collateralizableness) makes a bond essentially another form of money, unlikely to materially change consumption, contrary to mainstream views. War Bonds/Savings Bonds are more like the no early withdrawal deposit. They were quite important and heavily advertised in WWII USA & were not tradeable or usable as collateral. They were consciously designed as and successful as consumption-deferring anti-inflationary devices.

“The boss of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Thomas Hoenig told CNN that:

… the U.S. needs to raise interest rates to encourage individuals to save and avoid future asset bubbles. ”

Hasn’t Hoenig got a point about asset bubbles. The prevailing view seems to be that the Feds ZIRP has encouraged speculation in commodities and other risky assets. If that view is wrong why is it wrong?

thanks

Mike

Dear Mike (at 2011/05/31 at 10:41)

You may like to read this blog which might help you sort out this argument.

Monetary policy was not to blame

best wishes

bill

bill “At the same time, several countries, such as Germany, Switzerland, and Japan, experienced little to no increase in house prices, or even saw declines, notwithstanding persistently low interest rates in some cases.”

What that argument of yours always skirts around is that a whole industry was devoted to borrowing in Japan etc in order to lend in USA, Ireland, Spain, UK etc. That carry trade was huge and so saying that where the interest rates were low did not coincide with where the bubbles were seems desperately misleading.

Hi Bill,

thanks for the link but I don’t think that it addresses my question. I have heard Hoenig interviewed and his current concerns about bubbles have been to do with equities and commodities post GFC (during the Feds ZIRP period). Unless I am mistaken each bubble has its own pathology so it does not follow — to me at least — that if near zero rates were not responsible for the US housing bubble they are not, and will not, be responsible for a commodities and/or equities bubble.

Why isn’t it possible that ZIRP can fund speculation now (or over the last 2 years) in commodities and equities? Isn’t ZIRP funding — by means of low borrowing cost — speculation in food commodities that you blogged about the other day? “We should ban financial speculation on food prices”

thanks

Mike

Mike “near zero rates were not responsible for the US housing bubble”- I’d add that JAPANESE near zero rates WERE responsible for the US housing bubble and that the current Australian housing bubble could be being fed by near zero rates in USA etc.

> “please eliminate my competition and reduce my labour costs so I can extract more profit

From a dying horse? Why not have a stone-soup party and put the revived horse back to work, and breeding too? Do banksters really bite their own nose off and call it profit? Do they pass around a yearly trophy for bagging their own foot?

@Stone

The US housing bubble has had so much written about it and there appears to be enough to show that low rates on their own did not cause it — e.g. a multitude of things were involved including poor lending practices (a major reason). I agree with you about the carry trade: borrow US dollars, sell dollars and buy e.g. aussie dollars, invest in high yielding aussie instruments. The added advantage is the selling pressure on the US dollar means you make money on the currency fall as well (if you get out before the music stops).

I’d like to know why ZIRP isn’t contributing to the frothy (if to bubbly) commodities.

Just want to say thanks for a VERY educational blog, it has helped my economic understanding immensely.

A true internet gem!

Mike “I’d like to know why ZIRP isn’t contributing to the frothy (if to bubbly) commodities.”

-It really looks as though the MMTers are just turning a blind eye to this and pretending that the problem isn’t there. I guess if put in a corner, the MMT argument is that targeted regulations and taxes can extinguish any bubble. I guess MMTers realize they have an uphill struggle to convince people that they would be able to identify and deal with bubbles in that way. It is such a shame that rather than focusing on where MMT has holes that need urgent attention, MMTers instead sweep such problems under the carpet.