Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

Saturday Quiz – December 25, 2010 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for yesterday’s quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of modern monetary theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

If there is more “money” in the economy its value declines.

The answer is Maybe.

The question is mostly false but there are situations (rare) where it could be true – so maybe.

The question requires you to: (a) understand the difference between bank reserves and the money supply; and (b) understand the Quantity Theory of Money.

The mainstream macroeconomics text book argument that increasing the money supply will cause inflation is based on the Quatity Theory of Money. First, expanding bank reserves will put more base money into the economy but not increase the aggregates that drive the alleged causality in the Quantity Theory of Money – that is, the various estimates of the “money supply”.

Second, even if the money supply is increasing, the economy may still adjust to that via output and income increases up to full capacity. Over time, as investment expands the productive capacity of the economy, aggregate demand growth can support the utilisation of that increased capacity without there being inflation.

In this situation, an increasing money supply (which is really not a very useful aggregate at all) which signals expanding credit will not be inflationary.

So the Maybe relates to the situation that might arise if nominal demand kept increasing beyond the capacity of the real economy to absorb it via increased production. Then you would get inflation and the “value” of the dollar would start to decline.

The Quantity Theory of Money which in symbols is MV = PQ but means that the money stock times the turnover per period (V) is equal to the price level (P) times real output (Q). The mainstream assume that V is fixed (despite empirically it moving all over the place) and Q is always at full employment as a result of market adjustments.

In applying this theory the mainstream deny the existence of unemployment. The more reasonable mainstream economists admit that short-run deviations in the predictions of the Quantity Theory of Money can occur but in the long-run all the frictions causing unemployment will disappear and the theory will apply.

In general, the Monetarists (the most recent group to revive the Quantity Theory of Money) claim that with V and Q fixed, then changes in M cause changes in P – which is the basic Monetarist claim that expanding the money supply is inflationary. They say that excess monetary growth creates a situation where too much money is chasing too few goods and the only adjustment that is possible is nominal (that is, inflation).

One of the contributions of Keynes was to show the Quantity Theory of Money could not be correct. He observed price level changes independent of monetary supply movements (and vice versa) which changed his own perception of the way the monetary system operated.

Further, with high rates of capacity and labour underutilisation at various times (including now) one can hardly seriously maintain the view that Q is fixed. There is always scope for real adjustments (that is, increasing output) to match nominal growth in aggregate demand. So if increased credit became available and borrowers used the deposits that were created by the loans to purchase goods and services, it is likely that firms with excess capacity will react to the increased nominal demand by increasing output.

The mainstream have related the current non-standard monetary policy efforts – the so-called quantitative easing – to the Quantity Theory of Money and predicted hyperinflation will arise.

So it is the modern belief in the Quantity Theory of Money is behind the hysteria about the level of bank reserves at present – it has to be inflationary they say because there is all this money lying around and it will flood the economy.

Textbook like that of Mankiw mislead their students into thinking that there is a direct relationship between the monetary base and the money supply. They claim that the central bank “controls the money supply by buying and selling government bonds in open-market operations” and that the private banks then create multiples of the base via credit-creation.

Students are familiar with the pages of textbook space wasted on explaining the erroneous concept of the money multiplier where a banks are alleged to “loan out some of its reserves and create money”. As I have indicated several times the depiction of the fractional reserve-money multiplier process in textbooks like Mankiw exemplifies the mainstream misunderstanding of banking operations. Please read my blog – Money multiplier and other myths – for more discussion on this point.

The idea that the monetary base (the sum of bank reserves and currency) leads to a change in the money supply via some multiple is not a valid representation of the way the monetary system operates even though it appears in all mainstream macroeconomics textbooks and is relentlessly rammed down the throats of unsuspecting economic students.

The money multiplier myth leads students to think that as the central bank can control the monetary base then it can control the money supply. Further, given that inflation is allegedly the result of the money supply growing too fast then the blame is sheeted home to the “government” (the central bank in this case).

The reality is that the central bank does not have the capacity to control the money supply. We have regularly traversed this point. In the world we live in, bank loans create deposits and are made without reference to the reserve positions of the banks. The bank then ensures its reserve positions are legally compliant as a separate process knowing that it can always get the reserves from the central bank.

The only way that the central bank can influence credit creation in this setting is via the price of the reserves it provides on demand to the commercial banks.

So when we talk about quantitative easing, we must first understand that it requires the short-term interest rate to be at zero or close to it. Otherwise, the central bank would not be able to maintain control of a positive interest rate target because the excess reserves would invoke a competitive process in the interbank market which would effectively drive the interest rate down.

Quantitative easing then involves the central bank buying assets from the private sector – government bonds and high quality corporate debt. So what the central bank is doing is swapping financial assets with the banks – they sell their financial assets and receive back in return extra reserves. So the central bank is buying one type of financial asset (private holdings of bonds, company paper) and exchanging it for another (reserve balances at the central bank). The net financial assets in the private sector are in fact unchanged although the portfolio composition of those assets is altered (maturity substitution) which changes yields and returns.

In terms of changing portfolio compositions, quantitative easing increases central bank demand for “long maturity” assets held in the private sector which reduces interest rates at the longer end of the yield curve. These are traditionally thought of as the investment rates. This might increase aggregate demand given the cost of investment funds is likely to drop. But on the other hand, the lower rates reduce the interest-income of savers who will reduce consumption (demand) accordingly.

How these opposing effects balance out is unclear but the evidence suggests there is not very much impact at all.

For the monetary aggregates (outside of base money) to increase, the banks would then have to increase their lending and create deposits. This is at the heart of the mainstream belief is that quantitative easing will stimulate the economy sufficiently to put a brake on the downward spiral of lost production and the increasing unemployment. The recent experience (and that of Japan in 2001) showed that quantitative easing does not succeed in doing this.

This should come as no surprise at all if you understand Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

The mainstream view is based on the erroneous belief that the banks need reserves before they can lend and that quantitative easing provides those reserves. That is a major misrepresentation of the way the banking system actually operates. But the mainstream position asserts (wrongly) that banks only lend if they have prior reserves.

The illusion is that a bank is an institution that accepts deposits to build up reserves and then on-lends them at a margin to make money. The conceptualisation suggests that if it doesn’t have adequate reserves then it cannot lend. So the presupposition is that by adding to bank reserves, quantitative easing will help lending.

But banks do not operate like this. Bank lending is not “reserve constrained”. Banks lend to any credit worthy customer they can find and then worry about their reserve positions afterwards. If they are short of reserves (their reserve accounts have to be in positive balance each day and in some countries central banks require certain ratios to be maintained) then they borrow from each other in the interbank market or, ultimately, they will borrow from the central bank through the so-called discount window. They are reluctant to use the latter facility because it carries a penalty (higher interest cost).

The point is that building bank reserves will not increase the bank’s capacity to lend. Loans create deposits which generate reserves.

The reason that the commercial banks are currently not lending much is because they are not convinced there are credit worthy customers on their doorstep. In the current climate the assessment of what is credit worthy has become very strict compared to the lax days as the top of the boom approached.

Those that claim that quantitative easing will expose the economy to uncontrollable inflation are just harking back to the old and flawed Quantity Theory of Money. This theory has no application in a modern monetary economy and proponents of it have to explain why economies with huge excess capacity to produce (idle capital and high proportions of unused labour) cannot expand production when the orders for goods and services increase. Should quantitative easing actually stimulate spending then the depressed economies will likely respond by increasing output not prices.

So the fact that large scale quantitative easing conducted by central banks in Japan in 2001 and now in the UK and the USA has not caused inflation does not provide a strong refutation of the mainstream Quantity Theory of Money because it has not impacted on the monetary aggregates.

The fact that is hasn’t is not surprising if you understand how the monetary system operates but it has certainly bedazzled the (easily dazzled) mainstream economists.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Money multiplier and other myths

- Islands in the sun

- Operation twist – then and now

- Quantitative easing 101

- Building bank reserves will not expand credit

- Building bank reserves is not inflationary

Question 2:

A public works program that digs holes and fills them in again has exactly the same impact on current economic growth ($-for-$) as a private investment plan which constructs a new factory.

The answer is True.

This question allows us to go back into J.M. Keynes’ The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. Many mainstream economics characterise the Keynesian position on the use of public works as an expansionary employment measure as advocating useless work – digging holes and filling them up again. The critics focus on the seeming futility of that work to denigrate it and rarely examine the flow of funds and impacts on aggregate demand. They know that people will instinctively recoil from the idea if the nonsensical nature of the work is emphasised.

The critics actually fail in their stylisations of what Keynes actually said. They also fail to understand the nature of the policy recommendations that Keynes was advocating.

What Keynes demonstrated was that when private demand fails during a recession and the private sector will not buy any more goods and services, then government spending interventions were necessary. He said that while hiring people to dig holes only to fill them up again would work to stimulate demand, there were much more creative and useful things that the government could do.

Keynes maintained that in a crisis caused by inadequate private willingness or ability to buy goods and services, it was the role of government to generate demand. But, he argued, merely hiring people to dig holes, while better than nothing, is not a reasonable way to do it.

In Chapter 16 of The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, Keynes wrote, in the book’s typically impenetrable style:

If – for whatever reason – the rate of interest cannot fall as fast as the marginal efficiency of capital would fall with a rate of accumulation corresponding to what the community would choose to save at a rate of interest equal to the marginal efficiency of capital in conditions of full employment, then even a diversion of the desire to hold wealth towards assets, which will in fact yield no economic fruits whatever, will increase economic well-being. In so far as millionaires find their satisfaction in building mighty mansions to contain their bodies when alive and pyramids to shelter them after death, or, repenting of their sins, erect cathedrals and endow monasteries or foreign missions, the day when abundance of capital will interfere with abundance of output may be postponed. “To dig holes in the ground,” paid for out of savings, will increase, not only employment, but the real national dividend of useful goods and services. It is not reasonable, however, that a sensible community should be content to remain dependent on such fortuitous and often wasteful mitigations when once we understand the influences upon which effective demand depends.

So while the narrative style is typical Keynes (I actually think the General Theory is a poorly written book) the message is clear. Keynes clearly understands that digging holes will stimulate aggregate demand when private investment has fallen but not increase “the real national dividend of useful goods and services”.

He also notes that once the public realise how employment is determined and the role that government can play in times of crisis they would expect government to use their net spending wisely to create useful outcomes.

Earlier, in Chapter 10 of the General Theory you read the following:

If the Treasury were to fill old bottles with banknotes, bury them at suitable depths in disused coalmines which are then filled up to the surface with town rubbish, and leave it to private enterprise on well-tried principles of laissez-faire to dig the notes up again (the right to do so being obtained, of course, by tendering for leases of the note-bearing territory), there need be no more unemployment and, with the help of the repercussions, the real income of the community, and its capital wealth also, would probably become a good deal greater than it actually is. It would, indeed, be more sensible to build houses and the like; but if there are political and practical difficulties in the way of this, the above would be better than nothing.

Again a similar theme. The government can stimulate demand in a number of ways when private spending collapses. But they should choose ways that will yield more “sensible” products such as housing. He notes too that politics might intervene in doing what is best. When that happens the sub-optimal but effective outcome would be suitable.

But the answer is true because as long as the hole-digging operation is paying on-going wages to the workers who spend them then this will add to aggregate demand and hence income (economic) growth in the current period. The workers employed will spend a proportion of their weekly incomes on other goods and services which, in turn, provides wages to workers providing those outputs. They spend a proportion of this income and the “induced consumption” (induced from the initial spending on the road) multiplies throughout the economy.

This is the idea behind the expenditure multiplier. A private investment in the construction of a factory will have an identical effect. Over time, clearly building productive capacity is an important determinant of future economic growth. But if private spending is lagging then a public works scheme like that proposed is better than nothing.

The economy may not get much useful output from such a policy but aggregate demand would be stronger and employment higher as a consequence.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

Question 3:

Economists note that the automatic stabilisers in the government’s budget increase deficits (or reduce surpluses) in times of slack aggregate demand. This sensitivity of the budget outcome to the business cycle could be eliminated if the government followed a fiscal rule such that it had to balance its budget at all times.

The answer is False.

The final budget outcome is the difference between total federal revenue and total federal outlays. So if total revenue is greater than outlays, the budget is in surplus and vice versa. It is a simple matter of accounting with no theory involved. However, the budget balance is used by all and sundry to indicate the fiscal stance of the government.

So if the budget is in surplus it is often concluded that the fiscal impact of government is contractionary (withdrawing net spending) and if the budget is in deficit we say the fiscal impact expansionary (adding net spending).

Further, a rising deficit (falling surplus) is often considered to be reflecting an expansionary policy stance and vice versa. What we know is that a rising deficit may, in fact, indicate a contractionary fiscal stance – which, in turn, creates such income losses that the automatic stabilisers start driving the budget back towards (or into) deficit.

So the complication is that we cannot conclude that changes in the fiscal impact reflect discretionary policy changes. The reason for this uncertainty clearly relates to the operation of the automatic stabilisers.

To see this, the most simple model of the budget balance we might think of can be written as:

Budget Balance = Revenue – Spending = (Tax Revenue + Other Revenue) – (Welfare Payments + Other Spending)

We know that Tax Revenue and Welfare Payments move inversely with respect to each other, with the latter rising when GDP growth falls and the former rises with GDP growth. These components of the budget balance are the so-called automatic stabilisers.

In other words, without any discretionary policy changes, the budget balance will vary over the course of the business cycle. When the economy is weak – tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise and so the budget balance moves towards deficit (or an increasing deficit). When the economy is stronger – tax revenue rises and welfare payments fall and the budget balance becomes increasingly positive. Automatic stabilisers attenuate the amplitude in the business cycle by expanding the budget in a recession and contracting it in a boom.

So just because the budget goes into deficit doesn’t allow us to conclude that the Government has suddenly become of an expansionary mind. In other words, the presence of automatic stabilisers make it hard to discern whether the fiscal policy stance (chosen by the government) is contractionary or expansionary at any particular point in time.

The first point to always be clear about then is that the budget balance is not determined by the government. Its discretionary policy stance certainly is an influence but the final outcome will reflect non-government spending decisions. In other words, the concept of a fiscal rule – where the government can set a desired balance (in the case of the question – zero) and achieve that at all times is fraught.

It is likely that in attempting to achieve a balanced budget the government will set its discretionary policy settings counter to the best interests of the economy – either too contractionary or too expansionary.

If there was a balanced budget fiscal rule and private spending fell dramatically then the automatic stabilisers would push the budget into the direction of deficit. The final outcome would depend on net exports and whether the private sector was saving overall or not. Assume, that net exports were in deficit (typical case) and private saving overall was positive. Then private spending declines.

In this case, the actual budget outcome would be a deficit equal to the sum of the other two balances.

Then in attempting to apply the fiscal rule, the discretionary component of the budget would have to contract. This contraction would further reduce aggregate demand and the automatic stabilisers (loss of tax revenue and increased welfare payments) would be working against the discretionary policy choice.

In that case, the application of the fiscal rule would be undermining production and employment and probably not succeeding in getting the budget into balance.

But every time a discretionary policy change was made the impact on aggregate demand and hence production would then trigger the automatic stabilisers via the income changes to work in the opposite direction to the discretionary policy shift.

You might like to read these blogs for further information:

Question 4:

The private and public sectors cannot both reduce their levels of indebtedness if there is an external deficit.

The answer is True.

This is a question about the sectoral balances – the government budget balance, the external balance and the private domestic balance – that have to always add to zero because they are derived as an accounting identity from the national accounts. The balances reflect the underlying economic behaviour in each sector which is interdependent – given this is a macroeconomic system we are considering.

To refresh your memory the balances are derived as follows. The basic income-expenditure model in macroeconomics can be viewed in (at least) two ways: (a) from the perspective of the sources of spending; and (b) from the perspective of the uses of the income produced. Bringing these two perspectives (of the same thing) together generates the sectoral balances.

From the sources perspective we write:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that total national income (GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

From the uses perspective, national income (GDP) can be used for:

GDP = C + S + T

which says that GDP (income) ultimately comes back to households who consume (C), save (S) or pay taxes (T) with it once all the distributions are made.

Equating these two perspectives we get:

C + S + T = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

So after simplification (but obeying the equation) we get the sectoral balances view of the national accounts.

(I – S) + (G – T) + (X – M) = 0

That is the three balances have to sum to zero. The sectoral balances derived are:

- The private domestic balance (I – S) – positive if in deficit, negative if in surplus.

- The Budget Deficit (G – T) – negative if in surplus, positive if in deficit.

- The Current Account balance (X – M) – positive if in surplus, negative if in deficit.

These balances are usually expressed as a per cent of GDP but that doesn’t alter the accounting rules that they sum to zero, it just means the balance to GDP ratios sum to zero.

A simplification is to add (I – S) + (X – M) and call it the non-government sector. Then you get the basic result that the government balance equals exactly $-for-$ (absolutely or as a per cent of GDP) the non-government balance (the sum of the private domestic and external balances).

This is also a basic rule derived from the national accounts and has to apply at all times.

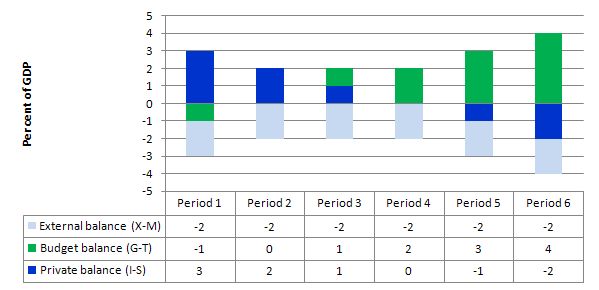

The following graph with accompanying data table lets you see the evolution of the balances expressed in terms of percent of GDP. I have held the external deficit constant at 2 per cent of GDP (which is artificial because as economic activity changes imports also rise and fall).

To aid interpretation remember that (I-S) > 0 means that the private domestic sector is spending more than they are earning; that (G-T) < 0 means that the government is running a surplus because T > G; and (X-M) < 0 means the external position is in deficit because imports are greater than exports.

If we assume these Periods are average positions over the course of each business cycle (that is, Period 1 is a separate business cycle to Period 2 etc).

In Period 1, there is an external deficit (2 per cent of GDP), a budget surplus of 1 per cent of GDP and the private sector is in deficit (I > S) to the tune of 3 per cent of GDP.

In Period 2, as the government budget enters balance (presumably the government increased spending or cut taxes or the automatic stabilisers were working), the private domestic deficit narrows and now equals the external deficit. This is the case that the question is referring to.

This provides another important rule with the deficit terorists typically overlook – that if a nation records an average external deficit over the course of the business cycle (peak to peak) and you succeed in balancing the public budget then the private domestic sector will be in deficit equal to the external deficit. That means, the private sector is increasingly building debt to fund its “excess expenditure”. That conclusion is inevitable when you balance a budget with an external deficit. It could never be a viable fiscal rule.

With an external deficit, it is impossible for both the government and the private domestic sector to reduce their overall debt levels by spending less than they earn.

In Periods 3 and 4, the budget deficit rises from balance to 1 to 2 per cent of GDP and the private domestic balance moves towards surplus. At the end of Period 4, the private sector is spending as much as they earning.

Periods 5 and 6 show the benefits of budget deficits when there is an external deficit. The private sector now is able to generate surpluses overall (that is, save as a sector) as a result of the public deficit.

So what is the economics that underpin these different situations?

If the nation is running an external deficit it means that the contribution to aggregate demand from the external sector is negative – that is net drain of spending – dragging output down.

The external deficit also means that foreigners are increasing financial claims denominated in the local currency. Given that exports represent a real cost and imports a real benefit, the motivation for a nation running a net exports surplus (the exporting nation in this case) must be to accumulate financial claims (assets) denominated in the currency of the nation running the external deficit.

A fiscal surplus also means the government is spending less than it is “earning” and that puts a drag on aggregate demand and constrains the ability of the economy to grow.

In these circumstances, for income to be stable, the private domestic sector has to spend more than they earn.

You can see this by going back to the aggregate demand relations above. For those who like simple algebra we can manipulate the aggregate demand model to see this more clearly.

Y = GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)

which says that the total national income (Y or GDP) is the sum of total final consumption spending (C), total private investment (I), total government spending (G) and net exports (X – M).

So if the G is spending less than it is “earning” and the external sector is adding less income (X) than it is absorbing spending (M), then the other spending components must be greater than total income.

Only when the government budget deficit supports aggregate demand at income levels which permit the private sector to save out of that income will the latter achieve its desired outcome. At this point, income and employment growth are maximised and private debt levels will be stable.

The following blogs may be of further interest to you:

- Barnaby, better to walk before we run

- Stock-flow consistent macro models

- Norway and sectoral balances

- The OECD is at it again!

Question 5 – Premium question:

It is clear that the central bank can use balance sheet management techniques to control yields on public debt at certain targetted maturities. However, this capacity to control the term structure of interest rates is diminished during periods of high inflation.

The answer is True.

I was going to use the term “economic impact” but decided against that because it might be misleading given that it would require a discussion of what an economic impact actually is. I consider an economic impact has to involve a discussion of the real economy rather than just the financial dimensions.

In that context you would then have had to consider two things: (a) the impact on private interest rates; and (b) whether interest rates matter for aggregate demand. And in a simple dichotomous choice (true/false) that becomes somewhat problematic.

I chose the alternative “impact on the term structure” because it didn’t require any consideration of the real economy but only the impact on private interest rates.

The “term structure” of interest rates, in general, refers to the relationship between fixed-income securities (public and private) of different maturities. Sometimes commentators will confine the concept to public bonds but that would be apparent from the context. Usually, the term structure takes into account public and private bonds/paper.

The yield curve is a graphical depiction of the term structure – so that the interest rates on bonds are graphed against their maturities (or terms).

The term structure of interest rates provides financial markets with a indication of likely movements in interest rates and expectations of the state of the economy.

If the term structure is normal such that short-term rates are lower than long-term rates fixed-income investors form the view that economic growth will be normal. Given this is associated with an expectation of some stable inflation over the medium- to longer-term, long maturity assets have higher yields to compensate for the risk.

Short-term assets are less prone to inflation risk because holders are repaid sooner.

When the term structure starts to flatten, fixed-income markets consider this to be a transition phase with short-term rates on the rise and long-term rates falling or stable. This usually occurs late in a growth cycle and accompanies the tightening of monetary policy as the central bank seeks to reduce inflationary expectations.

Finally, if a flat terms structure inverts, the short-rates are higher than the long-rates. This results after a period of central bank tightening which leads the financial markets to form the view that interest rates will decline in the future with longer-term yields being lower. When interest rates decrease, bond prices rise and yields fall.

The investment mentality is tricky in these situations because even though yields on long-term bonds are expected to fall investors will still purchase assets at those maturities because they anticipate a major slowdown (following the central bank tightening) and so want to get what yields they can in an environment of overall declining yields and sluggish economic growth.

So the term structure is conditioned in part by the inflationary expectations that are held in the private sector.

It is without doubt that the central bank can manipulate the yield curve at all maturities to determine yields on public bonds. If they want to guarantee a particular yield on say a 30-year government bond then all they have to do is stand ready to purchase (or sell) the volume that is required to stabilise the price of the bond consistent with that yield.

Remember bond prices and yields are inverse. A person who buys a fixed-income bond for $100 with a coupon (return) of 10 per cent will expect $10 per year while they hold the bond. If demand rises for this bond in secondary markets and pushes the price up to say $120, then the fixed coupon (10 per cent on $100 = $10) delivers a lower yield.

Now it is possible that a strategy to fix yields on public bonds at all maturities would require the central bank to own all the debt (or most of it). This would occur if the targeted yields were not consistent with the private market expectations about future values of the short-term interest rate.

If the private markets considered that the central bank would stark hiking rates then they would decline to buy at the fixed (controlled) yield because they would expect long-term bond prices to fall overall and yields to rise.

So given the current monetary policy emphasis on controlling inflation, in a period of high inflation, private markets would hold the view that the yields on fixed income assets would rise and so the central bank would have to purchase all the issue to hit its targeted yield.

In this case, while the central bank could via large-scale purchases control the yield on the particular asset, it is likely that the yield on that asset would become dislocated from the term structure (if they were only controlling one maturity) and private rates or private rates (if they were controlling all public bond yields).

So the private and public interest rate structure could become separated. While some would say this would mean that the central bank loses the ability to influence private spending via monetary policy changes, the reality is that the economic consequences of such a situation would be unclear and depend on other factors such as expectations of future movements in aggregate demand, to name one important influence.

Bonus Question 6:

The population of the North Pole is:

(a) 2,226 being the population of North Pole, Alaska, United States.

(b) Zero – No-one lives on the North Pole. The North Pole sits on a floating ice shelf, and cannot support any life.

(c) Bit hard to tell but Santa Claus, his partner and a few elves live there.

The answer is Option (c). Of-course!

the wording of question 4 is sloppy. both the domestic private and public sectors could reduce their indebtedness if the external deficit falls from it’s previous point but does not balance or go to surplus.

Dear Nathan Tankus (at 2010/12/26 at 5:30)

You asserted:

The wording is fine. If the public deficit is in surplus (of whatever magnitude), as long as the external deficit is positive (that is, in deficit of some magnitude), the private domestic sector overall is unable to record a surplus. So as a sector is must remain in deficit (and be accumulating debt).

Sorry.

best wishes

bill

“MV = PQ but means that the money stock”

So does the money stock mean medium of exchange supply, which would be currency plus demand deposits?

Bill –

You claimed

Aside from the dodgy premise, that statement is wrong because the country running the surplus doesn’t have to be accumulating assets at all – it could just be raising the value of its own currency. And even if it is, there’s no reason why they have to be denominated in the currency of the country running the deficit has to be directly involved at all. it could all be in a third currency – for instance, a lot of oil transactions are in US Dollars even though they don’t involve the USA.

As for question 6, the correct answer should be none of the above. North Pole isn’t the North Pole, there’s life under the ice, and the North Pole is only reputed to be where Santa Claus lives, while the mention of elves is evidence this reputation is undeserved.

Bill

Two of your questions have relevance to automatic stabilisers to some extent, but I am wondering about our future:-

In the UK at present, there seems to me to be a phoney feel to our current economic position and the buoyancy of some of the performance numbers. The cuts in the public sector budgets have been announced, but as yet, in many instances we do not yet know how they will be implemented. There is a little time yet for each department to determine its strategy about this before the new financial year starts in April. Most of the redundancies will have to happen in the New Year. We will then see the balance of job losses between those who are directly employed and count as public sector employees, and those who work on contract. I don’t remember any previous recession when the public sector has been reduced so much. In most past recessions, the public sector has been comparatively unscathed. The automatic stabilisers have then worked and the deficit has increased.

This time, I suggest it is different. Both groups of employees are effectively paid for from the public purse. As they move onto benefits, another department will pick up the cost of their support. However, their salaries will have ceased and net expenditure by the government will have been reduced as for each person, their salary is greater than their benefits and both are public expenditure.

The main effect which will bring the stabilisers into operation will be the extent to which the private sector is hit due to the decrease in demand resulting from the public sector job losses.

Is there any information that can be used to estimate the likely extent of these job losses?

The UK seems to me to be going into a region economically from which there is no recovery due to the automatic stabilisers. Am I correct in this assessment?

The Bonus Question ruined my day. I always thought Santa Claus is a seasonal worker living in Norway and working for an US beverage company.

Q2: A public works program that digs holes and fills them in again has exactly the same impact on current economic growth ($-for-$) as a private investment plan which constructs a new factory.

A2: But the answer is true because as long as the hole-digging operation is paying on-going wages to the workers … The workers employed will spend a proportion of their weekly incomes on other goods and services which, in turn, provides wages to workers providing those outputs. They spend a proportion of this income and the “induced consumption” (induced from the initial spending on the road) multiplies throughout the economy.

Your Q2 answer is wrong. Digging holes and filling them up is not economic growth. Consumption out of income is economic growth. But this consumption is not $-for-$ if compared to “private investment plan which constructs a new factory”. Savings leak.

“In this situation, an increasing money supply (which is really not a very useful aggregate at all) which signals expanding credit will not be inflationary.”

It seems to me that the money supply / medium of exchange supply (currency plus demand deposits) is extremely important. What would an economy look like if supply and demand were roughly in balance but the money supply / medium of exchange supply is incorrect?

Hopefully, this isn’t too off-topic for this particular post, but I just watched Steve Keen’s presentation on “Why Credit Money Fails,” and it struck me that he may have pointed toward a problem with MMT’s claim that only the government can create net financial assets sufficient to meet the private sector’s desire to save. Maybe. I’m new to MMT, so I’m struggling to think this through.

Specifically, he was taking issue with the theory that aggregate private profits are impossible. The familiar argument is that banks create money when they make loans, but they do not create the interest needed to pay back the loans, so unless the government creates that money, there won’t be enough money for all the debt to be paid back. Keen said that argument mistakes a stock for a flow. Money is a stock, but income is a flow, and a stock can revolve many times over in a flow, so, yes, in time, new income can be created sufficient to pay off nominal debts.

Keen didn’t say anything about MMT, so the rest of this is me groping about. I asked myself, could similar logic be applied to MMT such that after an initial “seed” of high-powered money, the private sector could create desired savings on its own? At first, I thought the answer obviously is no because for every private sector asset there is a corresponding liability. But not everything on the right side of a balance sheet is DEBT – equity also is on the right side. So if the private sector can create income sufficient to pay back the interest on private debt, it also can create income sufficient to convert all debt to equity. That may not be “net financial assets” as MMTers define the term, but it does seem to suggest that the private sector’s ability to generate savings is (theoretically) as great as its ability to generate money. Therefore new injections of high-powered money are necessary not so much because the private sector CAN’T generate its own savings as because, if history is any guide, it likely WON’T.

Bill,

Re #4.

Might this answer not always be true?

On the basis that MMT works on the denial of the existing national self-imposed constraints (of the government-budget-restraint), that is to say “there is no operational reason for…….” – thus that e self-imposed disability of the government to issue debt-free money to reduce its indebtedness, “irregardless” of what happens in the private sector, can be readily dismantled and undone via legislation that ends the private-credit, fractional reserve banking system of money creation, and restores the Constitutional(U.S.) right of the people to manage their monetary system.

Like here in Congressman Kucinich’s bill.

http://kucinich.house.gov/UploadedFiles/NEED_ACT.pdf

I know I could be wrong but it seems that under such a system, United States Money could be used to reduce government debt, even when the private sector was reducing its debt, for the simple reason that we would have a permanent money system of government issuance, rather than the pro-cyclical debt-money system, where money is created and destroyed in the so-called business cycle.

In proposing the 1939 Program for Monetary Reform, Douglas, Graham, Fisher et al stated the purpose of the reforms as being “It is intended to eliminate one recognized cause of great depressions, the lawless variability in our supply of circulating medium.”

This is accomplished in the Kucinich proposal.

Thanks.

I have a question for Q2 – digging holes and filling them in again vs construction of a new factory – investment in both of these would have the same impact on current economic growth. I wonder about the implications of the linkages that are associated with a particular activity in a particular sector? Such as labour intensive road construction which stimulates the gravel and bitumen suppliers verses flood irrigation – both in rural areas. Both activities involve lots of digging and lots of jobs can be created and both are good for the economy in the longer term – the road investment allows better access to markets and services, while the irrigation investment may improve the sustainability of farming. The jobs created will typically have low wages and therefore attract the vulnerable, which are likely to spend their wages rather than save and therefore the investment would also have a good induced effect. However, the intra-account affect of the different activities is slightly different. In the longer term the impact is also different..

thanks for the clarification!