I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

They have been smoking some doobies

I suddenly realised what has been going on all this time. They have been smoking some doobies – some real strong doobies and their heads are not what they used to be. How cool is that conclusion? It explains everything – why they typically miss the point of everything; why they say really dumb things most of the time; why they usually look half asleep; why they think down is up or up is down; why they continually think that what is good for them is bad for them and vice versa and all of that funk. I am so relaxed now – I actually thought there was a problem. But a bit of weed is doing it. I guess it is time for them to ease up on their intake though or their lack of concentration and awareness of reality will become entrenched. We need all the citizens we have thinking clearly and working together.

In relation to the rally in Washington, staged by the Daily Show’s Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert, it was reported in the Sydney Morning Herald that “fiery conservative commentator Rush Limbaugh mocked the Saturday event” saying that:

… it will give the tea party and other conservatives a chance to build voter turnout for Tuesday while Democrats go to Washington to “smoke some doobies” and listen to a “couple of half-baked comedians”.

He got it wrong though. I think he meant the deficit terrorists who attended Glen Beck’s (smaller function recently) were on the weed. The funniest thing I heard about Rush Limbaugh who raves about family values as part of his conservative agenda was “that he knows plenty about family values – given he has had so many”. Maybe he is smoking the doobies.

Maybe suggesting that the mainstream macroeconomists are smoked out dope-fiends is being too tough on them. Maybe they are just dumb. Joseph Stiglitz hints at that diagnosis.

On October 20, 2100, Joseph Stiglitz gave an interesting interview – Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz: Foreclosure Moratorium, Government Stimulus Needed to Revive US Economy – where he speculated on the skills possessed by those advocating austerity.

In that interview, which offered interesting ideas about the foreclosure problems now emerging, Stiglitz was asked whether deficits mattered. Here is the exchange:

AMY GOODMAN: Joe Stiglitz, the deficit, the battle cry of the Tea Party movement, of the Republicans, as well. Robert Rubin has weighed in, says any new stimulus plan is highly likely to be counterproductive. What do you think has to happen? Does the deficit matter? And how do you think it should be dealt with?

JOSEPH STIGLITZ: My view is we cannot afford not to stimulate the economy. So, you know, anybody that says we should go back to austerity or we should not have a second-round stimulus just doesn’t understand economics. And let me be very clear about this. If we don’t stimulate the economy, the economy is going to get weaker. When the economy gets weaker, tax revenues go down and expenditures go up. Already, more than 40 million Americans are on food stamps. Number of people on Medicaid is reaching record levels. So, revenues go down, expenditures go up, deficits get worse. If you stimulate the economy, then people get jobs, they spend money, tax revenues go up. Now, if we spend the money on investments-investments in education, technology, infrastructure-you grow the economy in the short run from the stimulus, you grow the economy in the long term because of the returns that you get on these investments.

It is like the ABC is to a little kid – one things follows another. All the smokescreens that have been put up by the mainstream conservatives never resonate like these basics:

1. The budget deficit is largely endogenous – that is, is driven largely by private spending decisions which impact on the budget outcome via the automatic stabilisers (changes in tax revenue and payments linked to economic activity levels).

2. Spending – both private and public – together creates aggregate demand which firms react to by increasing output and hiring people if there is idle capacity/resources.

3. Firms will not increase output and employment if they do not think they can sell the extra output. They form expectations of what they can sell by the direction of aggregate demand.

4. Cutting public spending (net) when private spending is not capable of taking up the slack will damage output and employment growth because it sends a signal to firms that there is not going to be growth in sales.

5. When output and employment growth stall, tax revenue falls and welfare payments rise quite apart from anything else the government might do. The budget deficit rises but with nothing good to show for it (like higher economic activity and employment levels).

6. When there are huge pools of idle capacity (machinery, office equipment etc and labour), then even if private spending is growing you still need further fiscal stimulus.

7. Households and firms are not Ricardian in the sense that they think ahead and calculate that every dollar of public net spending is a dollar they have to save so they can pay the budget deficits back later. No empirical evidence supports that crack-pot (doobie-driven) theory. It only gained credence because by then my profession was so lost in the smoke haze (and hatred of anything public) that anything that helped them make the case got a jersey!

8. If you want private firms to reduce their debt overall (that is, save overall) and if you also want the government to run a budget surplus then you better show how you will get an external (net exports) surplus big enough to “fund” both surpluses. Normally, that will not be case and the only way you can ensure the private sector can save overall is to run a budget deficit.

All of this is basic macroeconomics. So if you are inclined to advocate austerity right now rather than support further fiscal stimulus given the current state of national accounts (spending and output aggregates) the you:

just don’t understand basic economics.

… or you have been smoking the doobies too much! Simple as that. So either you are smoked out or dumb! Take your pick. The first used to be cooler but I doubt whether it is these days. Both explanations lead to the same end – stupidity!

As an aside, in the interview, Stiglitz then offered an analogy between the government borrowing (at low rates) and a private firm in the same position saying that if you had profitable investment opportunities “you would be irresponsible, you would be foolish, not to undertake those investments”.

At that point I would say the Nobel Prize winner is struggling with an understanding of the what opportunities a fiat currency presents. He chooses to perpetuate the false analogy between the government’s budget decisions and those pertaining to a private firm. There is no analogy. The bond yields paid by the government are irrelevant when it comes to determining whether some net spending will deliver net social benefits.

The costs to the government are the real resources used in the program not the $s that are created and spent. The private firm however has to bear in mind the cost of its financing as part of the private profit calculus it uses to determine whether a project is worthy of investment. The national government does not have to do this because it is not revenue-constrained – it issues the currency.

The hoopla by which it “borrows” and spends is just an ideological ploy in the fiat currency era. In the convertible currency systems the government had to finance its net spending but now it “borrows” unnecessarily.

Please read my blogs – Gold standard and fixed exchange rates – myths that still prevail and On voluntary constraints that undermine public purpose – for more discussion on this point.

All of this resonated with me when the US Bureau of Economic Analysis released the third-quarter National Account preview on October , 2010. The bottom line is that the US economy is not growing fast enough to make any inroads into the unemployment situation and is being saved from a worsening unemployment crisis by very low or zero labour force growth.

Which means that the unemployment crisis is being attenuated or masked by a hidden unemployment crisis (given participation rates have been falling in recent months).

I will come back to the BEA release soon. But this article caught my eye in the New York Times (October 27, 2010) – Tax Shortfalls Spur New Fear on Europe’s Recovery Bid.

You should read this in the context of the latest Eurostat data released on October 28, 2010 which showed that:

The euro area (EA16) seasonally-adjusted unemployment rate was 10.1% in September 2010, compared with 10.0% in August4. It was 9.8% in September 2009 … Among the Member States, the lowest unemployment rates were recorded in the Netherlands (4.4%) and Austria (4.5%) and the highest in Spain (20.8%), Latvia (19.4% in the second quarter of 2010), Estonia (18.6% in the second quarter of 2010) and Lithuania (18.2% in the second quarter of 2010). Compared with a year ago, the unemployment rate fell in seven Member States, remained stable in one and increased in nineteen.

Unemployment rates in the euro area have been consistently rising since early 2008. The monetary system has failed. It is only being propped up courtesy of the “fiscal interventions” of the ECB in contradiction to the Lisbon Treaty rules. They should scrap the system and reintroduce national currencies and/or create a single fiscal authority and allow it to pick up the demand slack.

You might like to see this NYT multimedia coverage of the The Austerity Zone: Life in the New Europe and related article – In Europe, a Mood of Austerity and Anxiety. They fail to trace the source of the problem to the basic design flaw in the monetary system underpinning the Euro and the ideologically-motivated recalcitrance of the Euro bosses.

Anyway, the aforementioned NYT artcle – Tax Shortfalls Spur New Fear on Europe’s Recovery Bid – notes that the “mathematics of austerity are getting harder” and argues that:

With economic conditions weaker than expected, tax revenue is coming up short of projections in parts of Europe. As a result, countries struggling with high deficits are now confronting the prospect that they will miss the budget deficit targets forced upon them this year by impatient bond investors.

To which one might say Duh!

The article notes that Greece is now likely to miss its target which was agreed as a part of its IMF intervention and that this “has spurred investor fears that the Greek government will be unable to close the gap and that Greece may ultimately be forced to restructure its mountain of debt with foreign investors.”

Investors are either smoking too many doobies or dumb if they ever thought otherwise. It is basic macroeconomics. We have to get used to that and construct our policy decisions accordingly.

It is sheer stupidity to invent a non-existent world (with Ricardians running everywhere) and then get surprised when your policy changes make the real world worse.

The article says that:

But it does highlight just how difficult it is for stagnating economies with rising unemployment rates to make fiscal adjustments exceeding 10 percent of their economic output in just a couple of years.

It is not difficult – it is virtually impossible. It was never a good bet – my understanding of basic macroeconomics told me that these countries were always going to encounter rising deficits.

There is simply no case for fiscal austerity in these nations. Some sector has to spend for there to be growth. With the non-government sector not meeting the challenge there is only one other show left in town. It is just basic macroeconomics – there are two sectors – government and non-government.

Now we can talk a bit about the latest National Income and Product Accounts, 3rd quarter 2010 (advance estimate) published by the US Bureau of Economic Analysis (October 29, 2010). You can also study the full publication release if you are interested in more detail.

The latest data shows that:

Real gross domestic product — the output of goods and services produced by labor and property located in the United States — increased at an annual rate of 2.0 percent in the third quarter of 2010 … In the second quarter, real GDP increased 1.7 percent … The increase in real GDP in the third quarter primarily reflected positive contributions from personal consumption expenditures … private inventory investment, nonresidential fixed investment, federal government spending, and exports that were partly offset by a negative contribution from residential fixed investment. Imports, which are a subtraction in the calculation of GDP, increased.

Closer scrutiny shows that while consumer spending is increasing it still remains fairly modest. The results also show that construction has falling back severely and investment in equipment and software is slowing. The data suggests that the early spurt in growth (early in 2010) stimulated some capital replacement (hence the realtively strong growth in investment in equipment in the second quarter) but that the rebuilding is over for now.

The data also shows that a major contributor to economic growth remans the fiscal stimulus spending from the federal government (it rose by 8.8 per cent in the September quarter).

There is no growth coming from the external sector as American continue to enjoy real terms of trade that deliver them benefits from imports outstripping exports.

Some commentators think the answer is to shift consumption away from imports to domestically produced goods but in a market system how are you going to achieve that?

In addition to the continued support from federal spending growth, US real output growth was heavily dependent on firms rebuilding their inventories which means that once they are replenished to levels considered normal output growth from this source will die again. The problem is rather dire.

The BEA says:

Real final sales of domestic product — GDP less change in private inventories — increased 0.6 percent in the third quarter, compared with an increase of 0.9 percent in the second.

So the 2.0 per cent headline figure looks very wan indeed when you subtract out the inventory cycle effect.

Should anyone be happy about these results? I wouldn’t be if I was a US citizen. When economic growth is insufficient to stop unemployment from rising you have a severe problem, especially when the growth in the labour force is around zero and has been consistently negative in recent quarters.

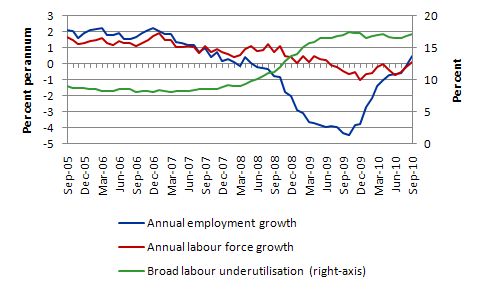

The following graph uses US Labour Force data available from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics and shows the evolution of labour force and employment growth and the broad labour underutilisation measure (green line) since September 2005.

This is a picture of a major collapse in employment growth which then induced a further reduction in labour force growth as unemployed workers (and new entrants) gave up looking – the so-called discouraged workers. The rise in unemployment would have been much worse had these workers remained in the labour force and kept looking for the non-existent jobs.

At present, annual employment growth is now close to zero (0.45 per cent in September 2010) and is just matching the labour force growth which is a sluggish 0.15 per cent (virtually static). This is an appalling state of affairs and shows how much fiscal intervention will be required.

I thought the comparisons provided by Dean Baker in his UK Guardian article (October 29, 2010) – Why growth still feels like recession were interesting. He said:

It may not be immediately obvious quite how weakly the economy is growing. First, we need a reference point. When an economy gets out of a step recession, it should be soaring, not just scraping into positive territory. In the first four quarters following the end of the 1974-75 recession, growth averaged 6.1%. In the four quarters following the end of the 1981-92 recession, growth averaged 7.8%. The growth rate averaged just 3.0% in the four quarters following the end of this recession.

And now the current growth is falling below that average and the main drivers of growth at present are in retreat.

There has to be another fiscal stimulus or else unemployment will continue to creep up and persist at the outrageously wasteful levels for years to come. The US is now going to experience long-term unemployment of the dimensions that Europe has endured for decades courteously of their irresponsible fiscal strategies (the strait-jackets imposed on them by the Maastricht rules).

Even though the fiscal rules categorically failed to work when it came to the crunch because of the strength of the automatic stabilisers in the face of the major private spending collapse the Maastricht treaty imposed a mentality that led to a suppression of aggregate demand over the last two decades. It also led to a host of supply-side policies (under the aegis of the OECD Jobs Study) being imposed which just worsened the problem. I cover this policy folly in detail in my 2008 book with Joan Muysken – Full Employment abandoned.

Stiglitz in the interview mentioned above was asked how much fiscal stimulus was needed at present and he replied:

Well, I think we really need $400, $500 billion a year. Part of the reason why we should try to keep those kinds of numbers in mind is to realize that we have a federal system, about a third of all spending is at the state and local level, and the states have balanced budget frameworks, which mean when the revenues go down, they have to cut back spending or raise taxes, which is very difficult in the current environment. And their revenues are going down. They depend very heavily on property taxes. Values of real estate have gone down 30, 40 percent, in some places 50 percent. And the result of this is that we’re laying off teachers. We’re laying off basic-those who provide basic services. So, while the government is coming to the end-the federal government is coming to the end of the stimulus, the states are retracting. We saw that in the September numbers on jobs. Sixty-seven thousand private-sector jobs were created-not enough for the new entrants in the labor force, less than half the amount we needed. But we lost, in total, 95,000 jobs …

I would suggest that is a conservative estimate of the required fiscal support that is needed just to keep things as they are.

While a major fiscal stimulus is needed, the politicians in the US are (as they butt their roaches or wonder which day it is) debating how large the cuts in social security payments (which feed almost $-for-$ into the spending stream) should be. With spending growth not robust enough to even create enough jobs for those who want them this is crazy stuff.

The stuff that emerges from a smoke haze.

Basic macroeconomics again – increase spending and employment will grow as long as the spending is targetted at creating jobs and not going into the bottom line of some corporation which little intention of spreading the largesse.

The sad news is that the only real policy response being broached is a renewed round of quantitative easing from the central bank. That will do virtually nothing to help the situation.

All it shows is that the government can produce liquidity without issuing debt. It would be far better spending to create jobs without issuing debt.

The bottom line is that (Source):

The fiscal stimulus is waning, the boost from inventories is fading, pent up investment demand is slowing …

You can get an idea of what advice the US government is getting with respect to dealing with this on-going crisis by examining the reports and input from the US Congressional Budget Office.

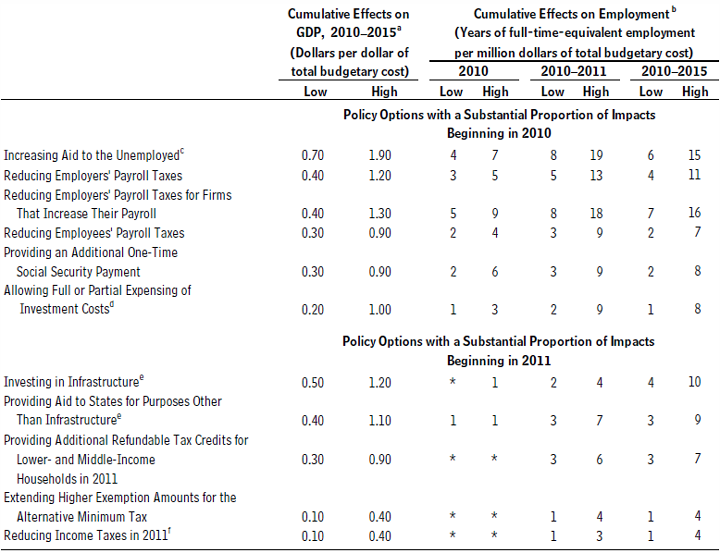

On February 23, 2010, the CBO Director made a Statement to the Joint Economic Committee, US Congress outlining Policies for Increasing Economic Growth and Employment in the Short Term.

If you read the statement and related research in detail you will see how biased these options are towards private market solutions and holding patterns.

The following Table is taken from that testimony (CBO Figure 1) and shows the policies considered and the estimated temporal impact. While some of these policies might be beneficial they all avoid the elephant in the room. Which is? Answer: the government can actually employ people directly – permanently – without much delay – and get those wages flowing into the spending stream.

They could get the greatest employment dividend by offering a Job Guarantee immediately. They will not because they are ideologically entrenched in their neo-liberal bunker. So the range of policy options being considered are heavily constrained by that way of thinking.

I know my friend Warren Mosler advocates a cut in the payroll tax and in the US setting that will help stimulate consumption. I have no problem with that but a much stronger employment response – albeit driven by the public sector – would be to make an unconditional job offer at a decent minimum wage to anyone who wanted them. The lessons from the work programs in the FDR period are still redolent – although in the smoke haze – only the clear-minded can see them.

To see why the GDP growth is insufficient in the US we can invoke Okun’s Law – arithmetic derived from aggregate macroeconomic relationships. This rule of thumb was named after the doyen of applied economics, US economist, the late Arthur Okun.

Accordingly, there is a link between the real GDP growth, labour productivity growth, and labour-force growth that feeds into movements in the unemployment rate. Thus, if GDP growth (increasing demand for labour) is greater than the sum of labour productivity (reducing labour requirements) and labour-force growth (with participation rates constant), the unemployment rate falls. However, if the sum of labour-force growth and labour productivity growth outstrips GDP growth, then the unemployment rate rises.

The Okun framework allows us to make predictions about changes in the unemployment rate given the rate of growth of GDP. Simply stated, labour productivity growth reduces the amount of labour required for each unit of output, while labour-force growth increases the number of jobs that have to be created if unemployment is to remain unchanged. So both growth rates place upward pressure on the unemployment rate.

If GDP growth is strong enough, the economy can absorb the labour supply and labour productivity growth. For the unemployment rate to be constant, real GDP growth has to equal the sum of labour-force growth and labour productivity growth. We can call this the required rate of GDP growth. Any better will lead to a falling unemployment rate, while any deficiencies in the required rate will see the unemployment rate rising.

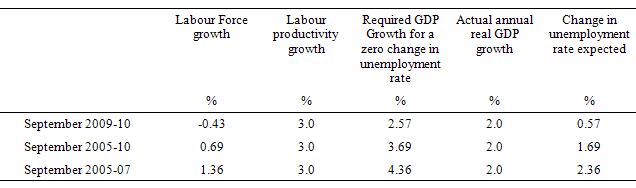

The US Bureau of Labor Statistics data (from graph above) shows that labour force growth in the last 12 months has been very low (-0.43 per cent). For the period since September 2005 it has averaged 0.69 per cent and for the growth period September 2005-07 it averaged a more normal 1.36 per cent per annum.

If the US economy grows more robustly then the labour force will start expanding towards that higher figure. The Table just simulates the three rates of growth mentioned for interest.

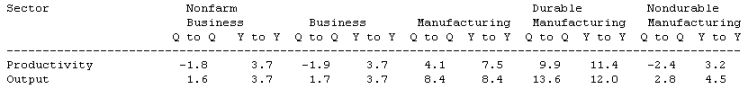

The US Bureau of Labor Statistics publishes productivity estimates for the US economy. The following table snippet is taken from their Table A September 2010 release.

So labour productivity is growing quite quickly. So what if annual growth in labour productivity continues at 3 per cent?

The following Table gives the rough rule of thumb for the likely direction in the US unemployment rate derived from Okun’s arithmetic. You can see that the required real GDP growth for a zero change in unemployment rate is the sum of the labour force and productivity growth rates. So it gets higher the higher is the labour force growth. As the economy expands, the hidden unemployed start coming back into the labour force and it makes it that much harder to put a dent in the unemployment pool.

With the actual real GDP growth rate of 2 per cent, the final column estimates what will happen over the next 12 months if these aggregates are maintained. You can see that unemployment rises regardless but the rise is suppressed by the pitifully negative labour force growth rate. That will not persist as GDP growth remains positive (albeit low).

The middle row assumption is more realistic (labour force growth of 0.69 per cent) which means that at the current real GDP growth rate the unemployment rate will rise above 10 per cent again over the next 12 months.

Baker (in his UK Guardian piece) agrees and says:

Just to add enough jobs to keep the unemployment rate constant, the economy has to grow at a 2.5% rate. In the absence of some unexpected change in policy, we will not see the economy growing at this pace any time soon, which means that the unemployment rate will be rising. We can expect it to cross 10% in the not-distant future and likely to remain in double-digit levels through most of 2010.

He says that the “outrageous part of this story is that the pain is completely preventable. We know how to create jobs. It is really simple; we just have to spend money – people work for it. Unfortunately, the fiscal scolds, the people who were too lost to see the largest financial bubble in the history of the world, are telling us that we have to cut our deficits and tighten out belts.”

With the mid-term elections tomorrow in the US and all the debate pointing in exactly the opposite direction I would be bunkering down if I was an employed American and saving like hell. The trouble with that reasonable private response is that it will worsen things.

The US is really caught in a smoke haze or the ignorance of their policy makers aided and abetted by those who have benefitted from the fiscal stimulus to date and don’t want anyone else to get a share.

Digression: Still searching for our bursting economy

In my search for the alleged bursting at the seams Australian economy – that is, what the bank economists are always telling us – I eagerly consulted the latest ABS House Price Indexes: Eight Capital Cities data for September 2010, which was released today.

If inflation is about to explode and labour market costs are subdued then perhaps it is going to come from a housing bubble.

Answer: no bubble. The data shows that capital city house prices are virtually unchanged over the September quarter. Flat = flat!

Conclusion

A basic understanding of macroeconomics tells us that further fiscal stimulus is required in the US. The same can be said for the UK and they are providing us all with the 1937-laboratory. To think that fiscal austerity will save the say is to misunderstand the basics of macroeconomics. Only a fool or a dope-crazed head would advocate such demolition in this day under these circumstances.

That is enough for today!

Hi Bill.

People seemed to at least enjoy themselves a bit at those “restore sanity” rallies. I suppose some doobage might have been smoked, but it seems that the left in the U.S. has been reduced to self-deprecating irony these days. One of the signs at the Washington rally read “Make awkward sexual advances, not war.”

I kind of wish I had gotten out to one of the local versions of the rally and brought a sign that said “We Need a Bigger Deficit” and also brought along a few copies of the article William Vickrey wrote in the ’90s with that title. I don’t suppose it would shock you to learn that a sizable proportion of our supposedly liberal commentators like to extol the wonderful virtues of Clinton’s balanced budgets which he achieved by gutting public spending in his second term in office and seem to think that is part of the formula for “getting back to sanity.”

We are so… well, rudely rebuffed.

Dear Bill

I wonder if you can help me unravel some confusion around the concept of bond sales as a “reserve drain” concept?

Deficit spending of 100 equates to an increase in reserves of 100, most of which will be excess, but not all – the US will want to increase reserves by 10 (and the UK and Canada by say 2-3). So surely bond sales equal to the full quantum of the deficit would ‘over-drain’ reserves, leading banks to have to borrow 10 from the CB? If this is right, it seems that whilst the first 90 (or 97-98) of bond sales will see ‘automatic’ demand from banks who are trying to jettison their excess reserves, a govt which (ignoring MMT) feels it needs to borrow to ‘finance’ the whole deficit, will need to ‘compete’ for the last 10 (or 2-3) of these bond sales in the marketplace, which may increase the marginal funding cost. Is this confused? Not sure I’ve seen a blog discussing this detail.

Many thanks for your continued prolific posting.

Best wishes

MMTP

I’ve been delving into the UK National Accounts stats for Q2 2010 – prompted by the latest data that shows that the outstanding debt in the household sector is still £1455 million as it has been for two years. That surprised me as I expected the Household sector to be repairing its balance sheet if we are to resume a genuine growth.

Now if MMT is correct in its predictions then that means there is a load of net add financial assets gone missing somewhere and I wanted to find out where it has gone.

When you look at the accounts you find that the majority of the money the government is ‘borrowing’ comes from the ‘Private Non-Financial Corporations’ sector. And then you look for the reason for the increase and you find: “This increase in net lending in the latest quarter was driven by increased net property income.”. Property I presume here is property in its widest sense – rather than just buildings.

And it looks like these organisations are paying out less in interest and dividends to their creditors yet continuing to gather rents from other sectors at the same or increasing level. I presume that differential has to come from government spending.

Perhaps I’m reading these things wrong, but it looks like it is companies rather than households that are getting the benefit of deficit spending at the moment (at least in the UK).

How does that get us out of this balance sheet crunch?

I think you might be onto something there Bill. Whether it’s caused by doobies, horse tranquilizers or full frontal lobotomies the results are starting to become comical. MMT quietly and efficiently determines the economic outcome of a particular policy action. We then pull up a deck chair and watch the comedy unfold.

It’s like one of those early B&W picture shows. The neo-libs are the villains with moustaches who have tied us all to the train tracks. Politicians and economists are a Laurel and Hardy double act, while the Federal Bank and IMF scream about in all directions like the bloody Keystone cops.

At the core of it all, it’s driven by rich elites manipulating the jealous instincts of the masses. I accidentally switched to the evil Glenn Beck on Fox the other day, I was rooted to my seat as he explained some fantasy economics on a blackboard. He rounded off his monstrous theories with a monologue appealing to irrational paranoia and jealousy. The gist of it was “Do you want all your hard work negated by some lazy assed union type down the corridor doing bugger all? … I certainly don’t! …. that’s why we must do this…. blah, blah blah!”

When I first visited the States in the 80’s, I was surprised by the number of mentally ill roaming freely on the sidewalks. In the UK, (those times) they would have been kept in public institutions. During a more recent visit I didn’t see so many nutters. Seems like the “free market” via Fox news has taken up the slack.

Neil – I have been doing the same thing and yes PNFC have grown their surpluses whilst HH are barely chipping away at their debt.

I’ve captured all the key data since 1987 in excel – let me know if you’d like me to email it.

Best

MMTP

“Real final sales of domestic product – GDP less change in private inventories – increased 0.6 percent in the third quarter, compared with an increase of 0.9 percent in the second.”

Thank you for explaining that Bill.

“Answer: no bubble. The data shows that capital city house prices are virtually unchanged over the September quarter. Flat = flat!”

What do we call it though when the value of my house increases more than 125% over about seven years? And various estimates put the average price somewhere from five to seven times average household income? I think we’ve definately HAD a bubble, one which is not growing at present. Or in the early stages of deflating?

Really only knowable in hindsight I suppose.

Outstanding post as always!

Elizabeth and I spent two full days with Stiglitz a couple of years ago. He definitely got it. There’s no explanation for his subsequent refusal to fully embrace mmt, apart from intellectual dishonesty and/or poor scholarship of one form or another. Same with Krugman, but the way. Dean Baker has been a lot better lately, but also fully understands mmt and could be a powerful influence that could take it mainstream, but hasn’t yet. Particularly on the social security issue, where he continues to see the war being lost but hasn’t yet taken out the mmt nuclear option to win the day.

Also, my 3 lead proposals do include the $8 federally funded job for anyone willing and able to work, as well as federal distributions to the state govts on a per capita basis.

http://www.moslerforsenate.com

best!

warren

MMT Proselyte,

Somewhat simplified:

The government controls its own cash position at the central bank very tightly, on a daily basis. That includes the net effect of flows in both directions – drains on its account from spending, and adds to its account from taxes and bond issuance.

The net result is that increases to both reserves and aggregate deposits that otherwise might have remained in the system due to net government spending are effectively reversed by the end of the day.

So, on a net basis, government spending per se produces no additional reserve requirement over time. So there is no requirement to take such a factor into account when draining reserves by bond issuance.

Increases in required reserves tend to follow the endogenous money creation trend of the commercial banking system.

JKH – really appreciate the reply. If I follow, changes in required reserves relate to horizontal money creation, not the vertical processes. I haven’t quite got my head around why this is – it feels as if you are begging the question. Surely if deficit spending is not ‘financed’ by bond issuance, it would result in an increase in deposits and therefore a (smaller) increase in desired reserves; so why would the G/CB feel the need to fully reverse deficit spending?

Is this discussed anywhere in slightly more detail? Perhaps I need to delve into Randall Wray’s book..

Granted that in practice the position management happens on an intraday basis; I still would have thought the OMO and longer-term sterilisation activity would be in the nature of a ‘drain’ on the excess reserves?

Best

MMTP

In the United States, banks purchase very little government bonds. So all deposits created by the government spending will be eliminated.

Some countries do have the banking system holding a large amount of government bonds, unlike the US. So if the government runs a deficit DEF in a period, and banks purchase a fraction f of the bonds issued, the extra deposits created would be (1-f)DEF. On this the reserve requirement (amount) would increase.

If one makes distinction between “asset-based” monetary system and “overdraft” type, the former will have the central bank purchasing some government bonds outright to help banks satisfy the reserve requirements. In the latter, banks’ indebtedness to the central bank will increase.

I’ve heard of supply-side economics.

I didn’t realize there was doobie-driven economics.

It all makes sense now.

MMTP,

Not sure quite how to get at your question, except by an additional example:

Think of a marginal transaction in deficit spending, say $ 100.

Suppose the reserve requirement is 10 per cent, or $ 10.

Consider two systems – one where the government issues bonds 1:1 against deficit spending (the self-imposed constraint); the other where it runs a “no bonds” system.

In the bond issuing system, the government spends $ 100, which if left alone, would increase bank deposits by $ 100 and reserves by $ 100. And the government would be overdraft $ 100 in its reserve account.

But it doesn’t leave it there. It issues $ 100 in bonds, which drains both bank deposits and reserve accounts and restores its own account to flat. It’s that last part which is the requirement under the self-imposed constraint of no overdrafts in that account.

Two assumptions there – I’m assuming the bonds are purchased by non-banks who pay for them from their deposits with banks. This is a fair assumption for the long run, because domestic commercial banks only hold a small fraction of issued bonds. And I’m assuming that the deposits that were drained by bond issuance, while not being the exact same deposits that were created by deficit spending, were of the same reservable type, so that the net change in reservable deposits through the cycle is zero. And that’s a fair assumption for illustration purposes.

With respect to the vertical impact of net deficit spending, the bonds are the primary form of vertical financial assets in the bond issuing system. The exceptions to this are the reserves that must be added to meet any increase in reserve requirements generated by the endogenous activity of the commercial banking system, any reserve adjustments that might otherwise be required for monetary policy at the margin, and any increases in the demand for currency issuance. But generally speaking, these are small relative to the size of the cumulative government budget deficit that is otherwise offset with bond issuance. And these adjustments are easy enough to do operationally through central bank purchases and sales of bonds.

Now assume a “no bonds” system. Then the government deficit spends and leaves the $100 deposit and the $ 100 reserves alone. Then the addition to required reserves is $ 10, which will already be available to the banking system as a whole since it can be part of the $ 100 of reserves created in the net spending process. So $ 10 of reserves becomes required and $ 90 of reserves becomes excess. That’s assuming the required reserve ratio remains the same under a “no bonds” system, an assumption that itself could be subject to speculative questioning.

In the no bonds system, you can think of the result for the government’s account at the central bank as just being left to accumulate an overdraft, or you can think of the consolidated government/central bank balance sheet in which the effect, because it is internal, is eliminated on consolidation – with reserves and currency as the remaining liability mix for the consolidated state entity, constituting the final forms of vertical financial assets in the no bonds system.

Great post, Bill, but I take issue with both the doobie theory and the stupid theory. I think that Robert H. Nelson has established pretty well in Economics as Religion: From Samuelson to Chicago and Beyond (Penn State, 2001) that it’s ideological fixation as an outgrowth of Western culture which lies at the bottom of these perplexing phenomenon of continually shooting oneself in the foot. These folks are neither stupid nor stoners; they are true believers. Their ideological presumptions aren’t falsifiable, because there is always an alternative explanation to call up when things don’t turn out as expected. That’s religiosity instead of science. These folks are just plain old religious fanatics in different garb. Instead of traditional theology, they have substituted “the invisible hand” and they worship numbers as divine ideas. They are Platonists of a sort, who don’t understand what Plato was talking about any more than their theologian predecessors did.

What about the left? I think that most professionals (academics and financial types) on center-left are cowed by the prevailing cultural mindset and the norms of a corresponding universe of discourse that marginalize or exclude anyone questioning key fundamentals, one of which is “sound money.” As Nelson observes, this is a key element of the cultural mindset owing to the religious heritage of the West, and one that pushes economics toward “godless Calvinism.” For a government to create money out of nothing is black magic.

Thus, an implicit conspiracy arises to conceal the actual operations of the monetary system and their macro implications. Even those who know are not willing to say. Several big names have been edging toward the boundary, but few have been willing to cross it. (Hats off to Jamie Galbraith.)

There is going to be either a gradual pulling back of the veil, until a critical mass builds, or else a sudden ripping of the veil, Wizard of Oz style, perhaps with an “the emperor is naked” moment. Hopefully, the constant hammering of MMT that is going on at various mainstream blogs is making a difference, although as yet it is rather imperceptible. On the other hand, shock could rip the veil.

There are a number of shocks that could easily arise, and they are only the ones that are foreseeable. I think that it unlikely that the world will make it through this crisis without such a shock. With seemingly years of deleveraging to go, there will be ample opportunity for surprises.

I found Ravi Batra’s The New Golden Age: The Coming Revolution Against Political Corruption and Economic Chaos (Palgrave Macmillan, 2006) interesting in this regard, in that it makes much of the present craziness understandable. While he doesn’t seem to understand modern monetary operations, he is writing from a historical perspective of social cycles and sees this as the end of a cycle in which the system breaks down owing to corruption by the acquisitive class that rules during this period. I would say that it fits in with Minsky’s analysis of the long financial cycle ending in Ponzi finance, Michael Hudson’s analysis of financial capitalism quite well, and Bill Black’s analysis of control fraud emanating from the top. With money controlling politics and the revolving door filling top positions, this system is rotten to the core.

Batra observers that the other classes besides the acquisitors, namely the warriors, intelligentsia and laborers, are in the service of the acquisitors. Therefore, economic professionals in academia, government, and business, as well as the media, all serve the interests of the acquisitors, including doing their messaging in order to keep the laborers, the people who do the actual production, in line with the acquisitors agenda. This agenda is to dedicate rising productivity to profit while reducing the real wage, which has happened in the US over the past thirty years. This necessitates increasing private debt or accepting a declining living standard. The objective of financial capitalism is to increase debt peonage, as Michael Hudson has documented.

It is simple to see that his cannot work and the acquisitors have put themselves in a bind. Increasing productivity increases supply, while reducing the real wage reduces income, hence, effective demand, relative to increasing supply. The result is that the difference must be made up with private debt, which is unsustainable over time. That is where we are now. So something has to give, and the acquisitors are not budging.

Therefore, conditions are in place for a social revolution, of which the Tea Party in the US is a manifestation, although it is fundamentally misguided owing to the propaganda that the acquisitors have marshaled to co-opt it. It will be interesting to see where this goes as the warrior-like laborers fight against their own interests by demanding austerity and “sound money.” According to Batra, a conflagration lies ahead when the laborers finally realize, “It’s the corruption, stupid.” He thinks it could alter capitalism as we know it, projecting somewhat a Schumpterian view although Batra’s analysis has a somewhat different orientation. Anyway, I found Batra’s book a good read.

Bill: With the mid-term elections tomorrow in the US and all the debate pointing in exactly the opposite direction I would be bunkering down if I was an employed American and saving like hell. The trouble with that reasonable private response is that it will worsen things.

Agreed. Time to take risk off rather than put it on heading into a storm.

JKH – thanks again. Your very clear exegesis presents bond issuance in an amount equalling the deficit spending simply as something that the G/CB does, stemming from the self-imposed constraints in place today. My problem I suppose is that I take on board the MMT tenet that “bond sales are simply a reserve drain” and try and overlay this with real world G/CB activity, asking the question: if the G/CB suddenly decided from now on only to issue that quantum of bonds which would drain reserves down to the desired amount, how much would they issue – and how would this quantum differ from the amount they actually issue in practice.

I suspected that the answer would be: under such a policy, the G/CB would issue slightly less in bonds. On reflection I think this approach would work mathematically, but another (obvious) approach is to issue for the full quantum of the deficit spending; both approaches would leave zero surplus reserves.

Intrigued as to what job you do that means you are so well-informed and yet have time for generous blog comments..

Best

MMTP

A few observations on the US election.

I recently watched a television debate between Rand Paul, the Republican (Tea Party) candidate for Senate in Kentucky, and the Democrat Jack Conway. Rand Paul argued from a household perspective regarding spending and taxes and was very convincing. I was in a crowd of Tea Party supporters watching the debate and tax reduction elicited great cheers as no other element of his platform did – not anti-abortion, anti-gun control nor anti-cap and trade. Interestingly most of the the supporters were young, under 30. Paul also states that decreased spending would accompany decreased taxes.

Conway was weak, agreeing with Paul on many issues and where he did not his arguments were hard to follow, at least compared to Paul’s simple straightforward explanations. He also misrepresented at least one of Paul’s positions.

Since the democrats have a hard time running on their uninspiring record (to put it mildly) they resorted to accusing Rand Paul of not being a real Christian because during college some 30 years ago he engaged in a hazing event that had a young woman pray to ”Aqua Buddha”. Pretty pathetic.

The view of many, many people in the US is that the stimulus failed since there is still 10% unemployment and that it has resulted in huge debt that endangers the future of the country. There is also tremendous anger at the bail-outs that are seen as give-aways to the elite. Lack of jobs remains by far the main issue.

Rand (Randal) Paul’s father, Ron Paul, a very conservative member of the House of Representatives from Texas who took a run at being the Republican candidate for President, is an in your face anti-imperialist, denouncing the US empire (his expression) and saying it causes resentment around the world and diverts money from pressing social needs in the US. Rand Paul, obviously familiar with his father`s views is at most a reluctant imperialist. He strongly opposes the military industrial complex (he directly quotes Eisenhower), and opposes the Iraq war as being unjustified and inflaming the Middle East against the US. He supports the Afghan invasion because there was evidence camps there were used to train people who attacked the US.

Clearly if the conservative household spending ideas of lower taxes associated with lower spending were put into effect the US would be plunged into a depression. Without doubt if the Obama administration had followed Warren’s remedy of reducing taxes or increasing spending to create employment and doing the bail-outs completely differently Obama would be wildly popular today. Unfortunately that was never to be. As clearly explained several years ago by John MacArthur, publisher of Harper’s Magazine, Obama was always the man of the financial industry and the like.

The US has its own peculiar mix of conservative ideas. On the economy confusion reigns and the household view of federal government finances completely dominates public discourse. In private top Republicans do seem to understand the deficit doesn’t necessarily matter much and use this knowledge to further their goals: low taxes for the well-to-do and expansion of the military. This then creates a very unequal society but with plenty of jobs and so is politically successful. Unfortunately almost all non-conservatives lack understanding of macro-economics and monetary operations and add to the confusion. Warren notes above that several prominent non-conservative economists are well aware of the macro realities but say nothing. Only Jamie Galbraith seems prepared to speak out. I think the others won’t say anything for fear of being excluded from the media and polite society because they would be seen as wing-nuts.

MMTP,

You’re asking some interesting questions in an interesting way, so let me try another perspective.

“If the G/CB suddenly decided from now on only to issue that quantum of bonds which would drain reserves down to the desired amount, how much would they issue – and how would this quantum differ from the amount they actually issue in practice.”

I see a couple of obstacles to actually doing this.

One is the existing institutional configuration, in which the central bank balance sheet is separate from the government balance sheet. What you have over time is the accumulation of bond liabilities on the government balance sheet. Over time as well, the central bank accumulates some of these bonds by purchasing them in the market. It does so in order to provide for the cumulative issuance of reserves and currency on its own balance sheet (commercial banks need reserves to “buy” currency from the central bank; central bank acquisition of assets creates those reserves, which are immediately “destroyed” when the banks “buy” the currency – the reserve liability is replaced by the currency liability.) So the total effect is gross bond issuance by the government, some of which is bought back, effectively in order to convert bond liabilities of the government to reserve and currency liabilities of the bank. This combination of activity effectively targets the liability mix of the total entity as between reserves, currency, and bonds.

Looking at the totality, this is an institutional arrangement with separate balance sheets working toward the desired liability mix. And given the balance sheet configuration, it is necessary for the government to issue more bonds than end up being floated net in the market place. At the same time, the bonds that end up being held on the central bank balance sheet become useful for the purpose of making reserve adjustments back and forth. That said, the margin of bonds required to make such adjustments typically is small relative to the size of the central bank balance sheet (e.g. bonds required to sell into the market when tightening up on reserve availability). However, the central bank bond portfolio did become practically useful in a larger way during the credit crisis, when the government sold government bills/bonds in order to take on private sector assets.

The second obstacle is that government bond issuance is a batch system rather than a continuous one. The government issues bonds and lets the market set the price for each batch. Because the reserve effect of each new batch would be disruptive if absorbed without further adjustment, it is necessary for the total entity to make some sort of adjustment around that process. In the existing system, it is left up to the central bank to go into the market and buy up previously issued bonds in order to offset the batch reserve drain that would arise otherwise from the government’s periodic issuance.

I think these two points – central bank reserve and asset management objectives and the discontinuity of bond issuance – go to the point of why it would be difficult to calibrate bond issuance alone precisely to the reserve target at any point in time. Central bank activity basically does that calibrating on a continuous basis once the government issues are released into the market place on a batch basis.

It might be possible to conceive of a different institutional arrangement whereby the central bank balance sheet and the government balance sheet are formally combined. However, this idea meshes more effectively with the “no bonds” proposal, I think. So long as the government continues to issue bonds priced in batch, some sort of market intervention capacity is probably desirable – which I think means some sort of inventory of bonds to work from, whether the balance sheets are separate or combined.

P.S.

Thanks for the personal comment/question. Time is not a problem when motivated to want to say something. My experience includes some close in work relevant to this sort of subject matter, but I’d prefer to leave it at that. And thanks for your interest.

Tom,

This was the one that really set me off:

Paulson figured out a way to engineer an unjust outcome seemingly right within his own religion! The Epistle aside, letting Lehman go without govt resolution is of a ‘sound mind’??? This really p—-d me off when I read it…

I intend to check out that book by Nelson.

Resp,

You should consider pre-emptively rebutting “if that were true, then how do you explain Zimbabwe?”

JOSEPH STIGLITZ: If you stimulate the economy, then people get jobs, they spend money, tax revenues go up.

mmm, well they did and the results didn’t happen that way.

Is it possible the problem is that Governments don’t often spend well and there should have been legal reforms introduced during this period rather than afterwards?

Why would another round of spending have a different result?

Seems to me that (non-finanancial sector) Corporate America has done very nicely (looking at profits and solid balance sheets) at the expense of the little guy who is now out of work and without a home with the blame sitting squarely at the feet of the Government and its economic advisors.

Ray, check out Bill’s post about the specific topic that you bring up, it should answer your concerns:

Entitled: The Fiscal Stimulus worked but was captured by profits

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=11911

Re: Warren’s comments on Stigitz, Krugman, Baker (and possibly Galbraith)

Yes, I certainly see “signs” that the three (or four) “get it”, but also signs that they do not. (Krugman (e.g.) was just out with a blog post “Accounting Identities”, which showed he at least gets the framework within which MMT resides.)

Now none of these folks are stupid, and all make enough good noise to indicate they don’t spend (a lot of) time in the doobie cloud, so what other explanation could there be? My guess is that they see MMT as simply another set of tools to be worked in with their “greater” economics learnings, and not as a separate, self-contained macro-system which (largely, at least) rejects neoliberalism. If this is how they view MMT, then it is much more understandable when they mix it in/flip-flop with neoliberalism.

Of course, that would still leave the problem of what they were missing, but at least that is a simpler problem than the outright rejection offered by the high lamas of monetarism as they view the world through their holy smoke.

New Keynesianism is a compromise with New Classicalism/Monetarism in order to be considered “serious” enough to have a place at the table. To paraphrase Upton Sinclair, if a person’s stature depends on not understanding something, he or she is unlikely to understand it, or let on anyway. When one is heavily invested in something, it is difficult to admit that one is wrong. If these folks were to publicly espouse MMT, their macro world would crumble around them.

Matt, when a supposed expert admits having to pray for an outcome instead of knowing what to do and why, he has just exposed himself as a non-expert and should resign forthwith instead of guessing or resorting to magical thinking. This is on the level of Lloyd Blankfein saying he is “doing God’s work.” Self-justification by association.

Thanks for perpetuating the myth that all stoners are stupid. We really need more of that. Keep em coming!

Dear Dave (at 2010/11/02 at 14:47)

We can have a bit of fun occasionally can’t we? Lighten up or should I say light up!

best wishes

bill

think I’ll light up after that RBA statement!

that wasn’t just hawkish, it was downright fiery…..and this after the “free swing” offered to it in October and the docile statement. This one was completely different….but what has changed to make them do bad tempered?

Hearing the CBA additional rate rise now being retracted….

R,

“In the United States, banks purchase very little government bonds. So all deposits created by the government spending will be eliminated.”

Are you saying that

CB Treasury Assets + Bank Treasury Assets = Deposits

?

JKH – that detailed explanation is v helpful – batch issuance vs balancing adjustments is an important distinction to keep in mind.

I have to conclude that as I try to proselytize about MMT, I can’t quite claim “deficit spending ensures that there is ‘automatic’ demand for all govt bond issuance”; but the reserve drain concept is nonetheless very powerful.

Didn’t meant to be nosy, of course, just impressed..

Best wishes

MMTP

Another plausible motivation for government austerity plans is that they are truly Green. These people are not dope fiends but conservationists keeping oil consumption low, by putting people out of work.

I once asked Dean Baker, How do mainstream economists think about peak oil? All he said was “They don’t.” But in all likelihood they do, just not publicly. They know that if gov’t cuts spending then jobs will be eliminated, and that in turn will help limit increases in the price of energy.

If the price of gasoline were ever to reach $US8/gal for more than six months, massive debt repudiation and civil unrest would follow. I don’t know what the equivalent price would be for similar effects elsewhere, but there is one.

What else could the austarians be afraid of?

RSJ,

No didn’t say that.

If there is a deficit spending of $100 the required bond issuance will be $100 and deposits remain the same. This is because bond issuance and taxes reduce deposits and spending creates (more of) them.

Of course there are loans which are made creating deposits in the process … and that is different.

So didn’t mean the equation you wrote down.

Right, but you said that the number of treasuries bought by the banks makes a difference to the number of deposits — that’s what confuses me.

If a bank sells a treasury to a pension fund, then does the number of deposits change?

What if a bank buys a treasury from a pension fund?

Or are secondary market treasury sales not important, so that only the treasuries bought directly form the gov. matter. In that case, all treasuries are bought by primary dealers. If a bank buys a primary dealer or divests itself of a primary dealer, will the number of deposits increase or decrease?

It’s interesting, because GS made itself into a bank, (was it the last non-bank PD?) so did that decrease/increase the number of deposits?

8. If you want private firms to reduce their debt overall (that is, save overall) and if you also want the government to run a budget surplus then you better show how you will get an external (net exports) surplus big enough to “fund” both surpluses. Normally, that will not be case and the only way you can ensure the private sector can save overall is to run a budget deficit.

Bill or someone,

Is there a simple diagram that shows how these relationships work. I would like to use them to explain to my mates why we need the Gov to create demand as needed to maintain steady employment.

I saw the Doobie Brothers 40 years ago at Festival Hall in Brisbane Queensland Australia. A big band with the crowed going off on timber floors created quite a memory. Surf is up, nice head high session today.

Punchy:

Bill recently did a blog that summarized the relationships in some diagrams. I found it very helpful:

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=12022#more-12022

Good luck,

PE Bird

Thanks pebird, much appreciated!