I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Unemployment is about a lack of jobs

Today I have reading a swag of literature which attempts to explain cross-country differences in change in unemployment and average duration of unemployment in the current recession. This issue has been topical in the US recently as the US Senate debates whether to extend unemployment benefits. The mainstream economics view is that the previous assistance caused the unemployment problem and a decision to extend the assistance will worsen it. However, you have to wonder what planet the proponents of these views are on. The overwhelming evidence is that the longer the recession the higher average duration of unemployment becomes and the larger the pool of long-term unemployed. The solution is always to stimulate employment growth. That simple truth is always lost on the mainstream. As you will see, among the proponents of the erroneous view that benefit provision has caused the worsening of the unemployment situation are researchers at JP Morgans. I would like to think that if the US government hadn’t bailed those bums out then these researchers might have been unemployed themselves. They could certainly use a dose of harsh reality.

In today’s financial news, one reads that “JPMorgan Earnings Increase 55%” ((Source).

If we go back a year or so we will recall that JP Morgan Chase was instrumental in the collapse of Lehman Brothers. The link will remind you of how they froze “$17 billion (£9.6 billion) of cash and securities belonging to Lehman on the Friday night before its failure” which is “what precipitated the liquidity crisis that embroiled the firm, forcing it into Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection on the morning of Monday, September 15”. This matter is still to go through the courts.

The collapse of Lehmans was the beginning of the credit crunch and the point at which the financial crisis became a real crisis which has led to massive unemployment.

JPMorgan was then a significant beneficiary of the US government bailout receiving $US25 billion. They have since repaid the loan.

In releasing the latest financial results, the CEO of Morgans was critical of the US government’s “proposed regulatory reforms” saying that “plans to bring trading of the instruments known as over-the-counter derivatives onto exchanges … could hit the bank’s revenue”.He also opposed the “proposed bailout fee on big banks” which he claimed was “a punitive bank tax”.

His pay last year? About $US16 million down from $US30 million in 2007 (poor lad!) (Source).

So it is a firm that has played a central role in creating the crisis which they have left far behind in their wake it seems, given their latest financial performance. I wonder how the unemployed in the US are feeling about JP Morgan and their ilk. For they are locked into extended periods of punishing unemployment with some living on no income and others (a minority) able to access the pitiful extended benefits provided by the US government.

Many of the unemployed will have run down their life savings keeping their families afloat which they will never restore while others had no savings in the first place and, for them, unemployment means poverty.

So in a moral sense one might ask what right does anyone within the JP Morgan institution have to make any statements about unemployment. In terms of my value system, the US government should never have bailed the banks out. Instead, they should have been wholly nationalised and major retrenchments of senior executives should have been made.

The fact that these characters blithely received public assistance at their time of need, which saved most of their jobs, when it was their decision-making incompetence that created the crisis, is an outrage.

I hope my words convey to you my anger about this sort of hypocrisy.

Now it is back to the blog!

In the WSJ last week (April 8, 2010) one Daniel Henniger wrote about – Joblessness: The Kids Are Not Alright and asked whether the US was prepared to “accept youth unemployment levels like Europe’s?”

He argued that unemployment duration (average weeks unemployed) in the US had risen sharply in the recent experience unlike any period previously. Long-term unemployment (defined in the US as jobless spells in excess of 27 weeks) represented “44% of all people unemployed in February. A year ago that number was 24.6%”. Note: in most nations long-term unemployment is defined as jobless spells in excess of 52 weeks.

Henniger’s main concern in this article is youth unemployment which is about 20 per cent for workers under 25 years of age. His point is that the US has never had this sort of problem before unlike Europe (and Australia and Britain to name some English-speaking nations) and risked locking in high rates of long-term unemployment because the strong employment growth, characteristic of past recoveries may not return this time. His argument is not germane to today’s blog.

But the point he is making is that whenever employment growth has been strong enough in the US, unemployment and the duration of unemployment has fallen fairly quickly.

This resonates with a lovely quote from Michael Piore (1979: 10):

Presumably, there is an irreducible residual level of unemployment composed of people who don’t want to work, who are moving between jobs, or who are unqualified. If there is in fact some such residual level of unemployment, it is not one we have encountered in the United States. Never in the post war period has the government been unsuccessful when it has made a sustained effort to reduce unemployment. (emphasis in original) [Unemployment and Inflation, Institutionalist and Structuralist Views, M.E. Sharpe, Inc., White Plains]

Contrary to this view is the mainstream economics view. For example, on April 13, 2010, the WSJ ran this story – Incentives Not to Work. The journalist quoted Larry Summers:

The second way government assistance programs contribute to long-term unemployment is by providing an incentive, and the means, not to work. Each unemployed person has a ‘reservation wage’ – the minimum wage he or she insists on getting before accepting a job. Unemployment insurance and other social assistance programs increase [the] reservation wage, causing an unemployed person to remain unemployed longer.

The aim of the article was to provide ammunition for the conservatives in the US Senate which are currently “debating whether to extend unemployment benefits for the fourth time since the recession began in early 2008”. If they decide to do that then the journalist claims “rarely has there been a clearer case of false policy compassion”.

Please read my blog – Extending unemployment benefits – an omen – for more discussion on this debate to disabuse yourselves of the nonsensical line that the provision of benefits causes unemployment.

Now we go back to JP Morgan. On March 17, 2010, the Economic Research Unit of JP Morgan put out this document – US: jobless benefits leaving a big mark on the macro data. The main contentions are:

While emergency benefits have been made available in all recent recessions, the terms of the current emergency benefits program have by far been the most generous, and have most likely had the largest impact on the macroeconomy.

In particular, the availability of these benefits has almost certainly played a significant role in the record rise in the average duration of unemployment. Consequently, they have also had a role in the stunning rise in the unemployment rate over the last two years.

Now you will see the context in which my introduction today was framed. JP Morgan’s lecturing us about unemployment.

They then rehearse the usual trite and unsubstantiated arguments about the provision of benefits. They claim that:

Jobless benefits have the potential to increase the unemployment rate through two channels. First, by softening the blow of losing a job, they allow unemployed persons to become more selective in what job offer they accept, thereby raising the average duration of unemployment and increasing the unemployment rate. Second, they may encourage people who would otherwise drop out of the labor force to be counted as jobseekers and therefore in the labor force.

This line is trotted out regularly by the mainstream economists who cannot face the fact that aggregate demand drives employment growth which mostly accounts for the dynamics of unemployment. A bevy of econometric attempts have been made (and I am very familiar with the literature and the complicated statistical techniques used) to “prove this claim”. The studies are always flawed, mostly in elemental ways and should be disregarded.

A rising unemployment rate can reflect a dynamic economy in its early stages of growth where lots of workers are churning in and out of employment. So the duration of jobless spells are short and endured by many in the workforce. The point here is that the churning is also seen on the demand side with lots of jobs being created and destroyed each month.

But in a major cyclical episode job destruction rates rise and job creation rates fall – very significantly. I did a three-year research project studying these labour market dynamics and the results are very consistent across economies and time.

When a major and protracted recession hits the labour market becomes stagnant and there is little job turnover and very little hiring. In this situation, the rising unemployment is always associated with longer durations as the waves of workers transit through the duration categories defined by the statisticians.

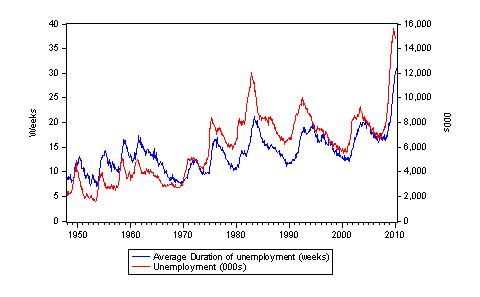

The following graph shows the average duration of US unemployment (weeks, left-axis) and total US unemployment (000s, right-axis) using monthly seasonally-adjusted data from January 1949 to March 2010. The data is from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

If you need help working out the relationship then here is a simple primer: when one goes up so does the other and when the other goes down so does the other one!

The JP Morgan researchers are claiming that the recent rises in unemployment and unemployment duration are benefit-driven.

What might have driven the unemployment movements? Think back to Piore’s quote above – “Never in the post war period has the government been unsuccessful when it has made a sustained effort to reduce unemployment.”

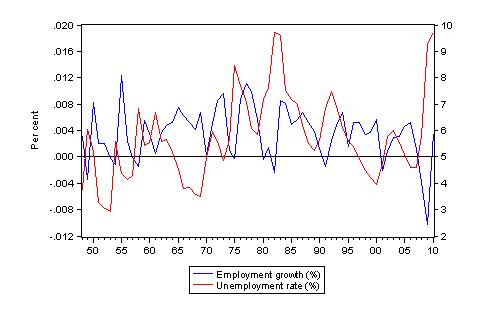

The following graph shows US employment growth (per cent – left axis) and the US unemployment rate (per cent – right axis) from 1948 to 2010. It demonstrates the close inverse relationship between jobs growth and the evolution of the unemployment rate, which is consistent with Piore’s observation. This inverse relationship is categorical and applies in all economies. The data is from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Now is there anything special about the current recession relative to past recessions? You can see an interesting History of US Recessions to check out the full duration of the various episodes. The data is mostly based on NBER analysis of recession dating.

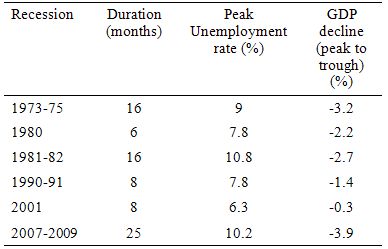

The following table summarises some of the characteristics of recent US recessions. It is clear that the current episode is by far the most severe both in amplitude and length. So given the relative severity of this downturn, it is no surprise that the rise in unemployment has been sharp and significant.

Further, given the unusually long period the US economy has been in recession this time, it is then a matter of accounting that unemployment duration will rise accordingly. The longer you hold aggregate demand at recessed levels, the longer is the period of stagnant labour demand, and the longer the period that people are unemployed. No surprise at all. The proportion of long-term unemployment is positively related to the length and breadth of the output gap.

In this context, it is a blessing that the US government has actually provided extended and emergency benefits. The demand collapse would have been greater had they not done this. The JP Morgan researchers at least realise that by “increasing the funds available to be spent by the unemployed, higher benefits should stimulate aggregate demand”.

But it is a disgrace that this sort of analysis is being pushed out into the markets by one of the largest and most unproductive institutions in the World (JP Morgan) and idiot journalists at the WSJ then think it is their job to propagate the indecency via the popular press.

In Chapter 3 of the recent IMF World Economic Outlook – entitled Unemployment dynamics during recessions and recoveries: okun’s law and beyond – a fairly detailed analysis of unemployment is provided. I will write about this document in more detail another time.

But in terms of the topic today the IMF note that:

For many advanced economies – where the financial crisis was centered – recovery is expected to be slow. In this context, persisting high unemployment may be the key policy challenge facing these economies as recovery gains traction …

Overall, the analysis presages sluggish employment growth during the recovery. Beyond the potentially slow recovery in output, the nature of the recent recession – financial crises combined with house price busts – in several advanced economies weigh against unemployment moderating any time soon. Indeed, based on the current path of policies, the forecasts presented suggest that although employment growth will turn positive in many advanced economies in 2010, the unemployment rate will remain high through 2011.

You won’t find reference to the provision of emergency unemployment relief causing the US unemployment to rise as much as it did. The analysis suggests that it was the multiplicative interaction between the financial damage (credit crunch and housing collapse) and the resulting contraction in aggregate demand that cause the real crisis to be more severe this time.

Underlying the JP Morgan approach is the claim that long-term unemployment displays strong irreversibility properties? That is, long-term unemployment will not fall when growth resumes and thus constitutes a constraint on growth that has to be tackled via supply-side remedies (for example, cutting benefits).

The JP Morgan approach is consistent with the mainstream view that the dynamics of unemployment are driven by supply side events. The orthodox approach, however, has been to consider long-term unemployment to be a (linear) constraint on a person’s chances of getting a job. The so-called negative duration effects are meant to play out through loss of search effectiveness or demand side stigmatisation of the long-term unemployed. That is, they become lazy and stop trying to find work and employers know that and decline to hire them. Over this period, skill atrophy is also claimed to occur.

And the provision of benefits exacerbate these negative factors.

So it has been common for mainstream economists and policy makers to postulate that there is a formal link between unemployment persistence, on one hand and so-called “negative dependence duration” and long-term unemployment, on the other hand. Although negative dependence duration (which suggests that the long-term unemployed exhibit a lower re-employment probability than short-term jobless) is frequently asserted as an explanation for persistently high levels of unemployment, no formal link that is credible has ever been established.

However, despite the lack of evidence, the entire logic of the 1994 OECD Jobs Study which marked the beginning of the so-called supply-side agenda defined by active labour market programs was based on this idea.

This agenda has seen the privatisation of the Commonwealth Employment Service, the obsession with training programs divorced from a paid-work context and the raft of pernicious welfare-to-work regulations. All have largely failed to achieve their aims.

Once you examine the dynamics of the data you quickly realise that short-term unemployment rates do not behave differently to long-term unemployment rates. The irreversibility hypothesis is unfounded.

The relationship between long-term unemployment and the unemployment rate is very close. As unemployment rises (falls), the proportion of long-term unemployment in total unemployment rises (falls) with a lag. Several studies have formally examined this relationship. My earlier work has found that a rising proportion of long-term unemployed is not a separate problem from that of the general rise in unemployment. This casts doubt on the supply-side policy emphasis that OECD governments have adopted over the last two decades. So while the mainstream economics profession may claim search effectiveness declines and this contributes to rising unemployment rates, the overwhelming evidence is that both are caused by insufficient demand. The policy response then is entirely different.

To argue that long-term unemployment is a constraint on growth and therefore needs supply-side programs rather than direct job creation, you would have to find that even during growth periods, long-term unemployment was resistant to decline.

Long-term unemployment declines as employment growth strengthens. There is no evidence available to support the irreversibility hypothesis?

The evidence very strongly supports the view that long-term unemployment rises and falls with net job creation. The stronger is employment growth the lower long-term unemployment is and vice-versa.

Please read my blog – Long-term unemployment – stats and myths – for more analysis of these issues.

The overwhelming evidence shows that unemployment is caused by a lack of jobs. And further that the unemployed cannot search for jobs that are not there. Please read my blogs – What causes mass unemployment? and – The unemployed cannot find jobs that are not there! – for more analysis of these issues.

Modern monetary theory (MMT) is clear – mass unemployment arises when the budget deficit is too low. To reduce unemployment you have to increase aggregate demand. If private spending growth declines then net public spending has to fill the gap. In engaging this debate, we also have to be careful about using experience in one sector to make generalisations about the overall macroeconomic outcomes that might accompany a policy change.

MMT tells us that state money introduces the possibility of unemployment. There is no unemployment in non-monetary economies. Repeating a familiar theme, it is clear that the government does not have to raise taxes or issue a financial asset (bond) in order to spend. So the government in a fiat monetary system is not “revenue-constrained”.

Intuitively this is hard to accept because we are so wedded to the idea that nothing is certain but death and taxes and that the latter is to raise money for governments to spend. The issue of taxation is also very emotional – as we see in some comments on my blog – taxation is linked by conservatives to concepts of slavery; loss of freedom; etc.

So the idea of a government that is not revenue-constrained is hard to grasp at the emotional level.

What this all means is that we have to analyse the functions of taxation in a different light. As a background to this discussion you might like to read this blog – Functional finance and modern monetary theory.

MMT shows that taxation functions to promote offers from private individuals to government of goods and services in return for the necessary funds to extinguish the tax liabilities.

So taxation is a way that the government can elicit resources from the non-government sector because the latter have to get $s to pay their tax bills. Where else can they get the $s unless the government spends them on goods and services provided by the non-government sector?

The mainstream economists conceive of taxation as providing revenue to the government which it requires in order to spend. In fact, the reverse is the truth.

Government spending provides revenue to the non-government sector which then allows them to extinguish their taxation liabilities. So the funds necessary to pay the tax liabilities are provided to the non-government sector by government spending.

It follows that the imposition of the taxation liability creates a demand for the government currency in the non-government sector which allows the government to pursue its economic and social policy program.

The government is able to purchase labour from the non-government person as long as the tax regime is legally enforceable. The non-government person will also accept the government money because it is the means to get the $s necessary to pay the taxes due.

This insight allows us to see another dimension of taxation which is lost in mainstream economic analysis. Given that the non-government sector requires fiat currency to pay its taxation liabilities, in the first instance, the imposition of taxes (without a concomitant injection of spending) by design creates unemployment (people seeking paid work) in the non-government sector.

The unemployed or idle non-government resources can then be utilised through demand injections via government spending which amounts to a transfer of real goods and services from the non-government to the government sector.

In turn, this transfer facilitates the government’s socio-economics program. While real resources are transferred from the non-government sector in the form of goods and services that are purchased by government, the motivation to supply these resources is sourced back to the need to acquire fiat currency to extinguish the tax liabilities.

Further, while real resources are transferred, the taxation provides no additional financial capacity to the government of issue.

Conceptualising the relationship between the government and non-government sectors in this way makes it clear that it is government spending that provides the paid work which eliminates the unemployment created by the taxes.

So it is now possible to see why mass unemployment arises. It is the introduction of State Money (defined as government taxing and spending) into a non-monetary economy that raises the spectre of involuntary unemployment.

As a matter of accounting, for aggregate output to be sold, total spending must equal the total income generated in production (whether actual income generated in production is fully spent or not in each period).

Involuntary unemployment is idle labour offered for sale with no buyers at current prices (wages). Unemployment occurs when the private sector, in aggregate, desires to earn the monetary unit of account through the offer of labour but doesn’t desire to spend all it earns, other things equal.

As a result, involuntary inventory accumulation among sellers of goods and services translates into decreased output and employment.

In this situation, nominal (or real) wage cuts per se nor cutting unemployment benefits will not clear the labour market, unless those cuts somehow eliminate the private sector desire to net save, and thereby increase spending. This is not likely.

So we are now seeing that at a macroeconomic level, manipulating wage levels (or rates of growth) would not seem to be an effective strategy to solve mass unemployment.

MMT then concludes that mass unemployment occurs when net government spending is too low.

To recap: The purpose of State Money is to facilitate the movement of real goods and services from the non-government (largely private) sector to the government (public) domain.

Government achieves this transfer by first levying a tax, which creates a notional demand for its currency of issue.

To obtain funds needed to pay taxes and net save, non-government agents offer real goods and services for sale in exchange for the needed units of the currency. This includes, of-course, the offer of labour by the unemployed.

The obvious conclusion is that unemployment occurs when net government spending is too low to accommodate the need to pay taxes and the desire to net save.

This analysis also sets the limits on government spending. It is clear that government spending has to be sufficient to allow taxes to be paid. In addition, net government spending is required to meet the private desire to save (accumulate net financial assets).

It is also clear that if the Government doesn’t spend enough to cover taxes and the non-government sector’s desire to save the manifestation of this deficiency will be unemployment.

Keynesians have used the term demand-deficient unemployment. In MMT, the basis of this deficiency is at all times inadequate net government spending, given the private spending (saving) decisions in force at any particular time.

Shift in private spending certainly lead to job losses but the persistent of these job losses is all down to inadequate net government spending.

So we can finish by reflecting on the quote from Michael Piore “Never in the post war period has the government been unsuccessful when it has made a sustained effort to reduce unemployment”.

Conclusion

I am calm again!

That is enough for today.

“Unemployment is about a lack of jobs”

Are you sure it is not about a lack of retirees?

“I wonder how the unemployed in the US are feeling about JP Morgan and their ilk.”

Is he** too good a place for them?

“MMT tells us that state money introduces the possibility of unemployment.”

One way to put this is that there is no unemployment over at Meerkat manor. Everyone works there!

Not to add fuel to the flames but here is Kevin Drum commenting on a Fortune Magazine article:

“So corporate profits tripled during a recession year in which sales fell 8.7%. Has that ever happened before? The key to this, of course, was layoffs: “In 2009, the Fortune 500 shed 821,000 jobs, the biggest loss in its history – almost 3.2% of its payroll.” In other words, we have now been through a recession in which, essentially, nobody has really suffered except for all the workers who have been let go. Wall Street is doing great. Corporate profits are doing great. The stock market is recovering. Is it any wonder that Republicans don’t really care about any further fiscal stimulus? Their constituency is doing fine, thankyouverymuch.”

Bill,

you have competition!

Hurry up with the MMT Sims!

Obama administration requests federal deficit game:

“The Obama administration in the U.S. has apparently requested that Microsoft create a “deficit-reduction video game”, according to a report by newspaper USA Today.

http://www.usatoday.com/news/washington/2010-04-12-deficit_N.htm?csp=hf

In a wider article on the US federal deficit, the article claims that fiscal commission co-chair Erskine Bowles has “been in touch” with Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer about creating the game.

Although no other details of the proposed title are given, Democratic senator Bob Kerrey is quoted as suggesting that the game could “go viral”.

The U.S. national debt is currently put at $12.8 trillion and the game is intended to help illustrate the difficulty, and necessity, of reducing the figure.”

I am a 3D artist/animator if you need help! (I do game design too)

Professor or anyone else:

This is slightly off topic (not much). One the biggest challenges, IMO, that US and other countries face is extremely high income inequality. Income inequality not only threatens economic stability but it also threatens democracy. How would MMT, if it does at all, address income inequality?

MMT posits that the government can maintain employment through spending when the private sector is unable to provide sufficient opportunities, and that this spending is not inflationary provided that real resources are available for the population. One way to do accomplish this employment is through a job guarantee.

A job guarantee at a livable wage (with health care benefits) places a floor on wages while providing maintenance of skills (not just technical skills, but also reinforcing work habits and keeping workers engaged in the labor marketplace. This addresses income inequality in a number of ways: 1) reduces household asset loss through spend down after losing a job, 2) by sustaining aggregate demand, the probability of private employment growth is increased, 3) improves inter-generational income growth by reducing childhood trauma/dislocation thereby increasing education effectiveness, 4) and so on and so forth.

The benefits are so numerous, and given the costs of unemployment benefits (a majority of which would be shifted to the job guarantee) that the incremental cost is not what you might expect, especially after seeing the impact of financial institution bailouts.

The funny thing is, if there was a job guarantee then it would be much easier to just go ahead and let financial institutions fail and have them work out their deleveraging problems on their own schedule – households would still have to share in the loss of higher income private sector jobs, but the impact would be lessened significantly. Letting the banks fail (or taking them over temporarily) would also reduce the incomes of those most responsible for the crisis – which would have additional income equalization benefits.

pebird:

Thank you. I understand and agree with what you are saying but my concern is whether that is enough to address the level of inequality. Some economists have suggested using tax policy to address income inequality but my understanding of MMT is that tax policy should be used to effect aggregate demand.

IMO, fiscal policy has been used to exacerbate the level of inequality. Is it a matter of reversing policy?

I find it interesting that those whose ideas CAUSED this unemployment now tell us that unless we listen to and follow their even more radical ideas, the same unemployment they caused will become permanent.

I read yesterday that science is now telling us that each black hole is actually the entry way to an alternate universe. No doubt we have a black hole very close to us then, and that it’s alternate universe has an over abundance of very smart economists. How else to explain the very short supply of them we have here?

Recent data from New Zealand shows that while their government received only $6 million from mining revenue, the companies mining their country received $6 BILLION (and no I’m not having a Barnaby moment). If these figures are anything to go by then if we nationalised Australia’s mining industry we could reduce our mining by over 50% and strictly regulate its impact, reducing our carbon footprint phenomenally and at the same time earning 500% more in income for our country. Any displaced mine workers could be redeployed in an expanded public service sector as could all those on the dole queue, funded by Australia’s vastly increased mining earnings. Think better roads, health, education, public facilities and culture not to mention full employment, regaining our national sovereignty and reducing greenhouse emissions. Come back Nugget Coombs…all is forgiven!