I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Budget deficits do not cause higher interest rates

I have always been antagonistic to the mainstream economic theory. I came into economics from mathematics and the mainstream neoclassical lectures were so mindless (using very simple mathematical models poorly) that I had plenty of time to read other literature which took me far and wide into all sorts of interesting areas (anthropology, sociology, philosophy, history, politics, radical political economy etc). I also realised that the development of very high level skills in empirical research (econometrics and statistics) was essential for a young radical economist. Most radicals fail in this regard and hide their inability to engage in technical debates with the mainstream by claiming that formalism is flawed. It might be but to successfully take on the mainstream you have to be able to cut through all their technical nonsense that they use as authority to support their ridiculous policy conclusions. That is why I studied econometrics and use it in my own work. It was strange being a graduate student. The left called be a technocrat (a put-down in their circles) while the right called me a pop-sociologist (a put down in their circles). I just knew I was on the right track when I had all the defenders of unsupportable positions off-side. But an appreciation of the empirical side of debates is very important if a credible challenge to the dominant paradigm is to be made. That has motivated me in my career.

The Australian Treasury released a paper last week – Reconsidering the Link between Fiscal Policy and Interest Rates in Australia – which “examines the empirical relationship between government debt and the real interest margin between Australian and US 10 year government bond yields”.

In English, that means they were seeking to examine whether increasing budget deficits pushed up interest rates which is one of the conservative claims to butress their case against the use of fiscal policy as a counter-stabilisation tool (that is, to correct aggregate demand failures).

An often-cited paper outlining the ways in which budget deficits allegedly push up interest rates is – Government Debt – by Elmendorf and Mankiw (1998 – subsequently published in a book in 1999). This paper was somewhat influential in perpetuating the mainstream myths about government debt and interest rates. Clearly Mankiw still believes in the logic given it occupies a central part of his macroeconomics textbook.

Elmendorf at the time was on the US Federal Reserve Board. It is a pity for the American people that he is now the director of the US Congressional Budget Office.

If you read the paper (and frankly it will waste your precious time to do so), you will note that the paper’s motivation was the rise in public debt between 1980 and 1997. The same sort of rhetoric was being used then as now – spiralling (out of control) public debt. Did the sky fall in then? Answer: No! The rise in the debt presented no problems – interest rates didn’t balloon and inflation didn’t become accelerate out of control.

Elmendorf and Mankiw state that the “conventional” view, which is “held by most economists and almost all policymakers”, considers that:

… the issuance of government debt stimulates aggregate demand and economic growth in the short run but crowds out capital and reduces national income in the long run.

Their depiction of the alternative to the convention view is – Ricardian equivalence – which alleges that:

… the choice between debt and tax finance of government expenditure is irrelevant … [because] … a budget deficit today … [requires] … higher taxes in the future. Thus, the issuing of government debt to finance a tax cut … [or any net spending increase] … represents not a reduction in the tax burden but merely a postponement of it. If consumers are sufficiently forward looking, they will look ahead to the future taxes implied by government debt. Understanding that their total tax burden is unchanged, they will not respond to the tax cut by increasing consumption. Instead, they will save the entire tax cut to meet the upcoming tax liability; as a result, the decrease in public saving (the budget deficit) will coincide with an increase in private saving of precisely the same size. National saving will stay the same, as will all other macroeconomic variables.

I have dealt with this view extensively in a number of blogs – Pushing the fantasy barrow – Even the most simple facts contradict the neo-liberal arguments – Deficits should be cut in a recession and We are sorry – for more detailed discussion on the folly of Ricardian equivalence

Ignoring the fact that the description of a government raising taxes to pay back a deficit is nonsensical when applied to a fiat currency issuing government, the Ricardian Equivalence models rest of several key and extreme assumptions about behaviour and knowledge. Should any of these assumptions fail to hold (at any point in time), then the predictions of the models are meaningless.

The other point is that the models have failed badly to predict or explain key policy changes in the past. That is no surprise given the assumptions they make about human behaviour.

There are no Ricardian economies. It was always an intellectual ploy without any credibility to bolster the anti-government case that was being fought then (late 1970s, early 1980s) just as hard as it is being fought now. Stacks of doctoral theses were written about it – justifying it, etc. None should have passed because they had no knowledge value at all. PhDs are meant to be awarded for advances in knowledge.

Everytime you read an article or chapter or whatever that invokes Ricardian Equivalence to justify its thesis – stop reading immediately and finds something better to do.

In terms of the “conventional” analysis, Elmendorf and Mankiw state that in the short-run an increase in the budget deficit (say via a tax cut with spending constant):

… raises households’ current disposable income and, perhaps, their lifetime wealth as well. Conventional analysis presumes that the increases in income and wealth boost household spending on consumption goods and, thus, the aggregate demand for goods and services … This Keynesian analysis provides a common justification for the policy of cutting taxes or increasing government spending (and thereby running budget deficits) when the economy is faced with a possible recession.

So far so good. This account is not at odds with Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) except that the decision to run budget deficits does not turn on the state of the business cycle. It depends on the state of non-government spending and saving decisions. The aim of the budget deficit is to ensure aggregate demand gaps do not occur which would undermine output and employment growth.

The prior choice that the government has to make is the mix of public and private activity at full capacity. How much public output is required to advance the socio-economic mandate that the political process has bestowed on the government? That is the question that has to be considered initially.

The answer sets the full-employment size of government. Then the government has to manage fluctuations in that size when private spending fluctuates. If private spending increases above this implied “size” then the government would tax the private purchasing power away. If the non-government spending fell below the necessary level (or rate of growth) then the budget deficit has to rise temporarily to fill the gap and maintain growth.

This is the way in which counter-stabilisation policy is conducted. But it may be appropriate (and typically will be) within this process for the government to continuously run budget deficits to ensure the non-government is continuously net saving in the currency of issue. So deficits are not just about bailing out recessions.

But then the wheels fall off in the Elmendorf and Mankiw paper. They say:

Conventional analysis also posits, however, that the economy is classical in the long run. The sticky wages, sticky prices, or temporary misperceptions that make aggregate demand matter in the short run are less important in the long run. As a result, fiscal policy affects national income only by changing the supply of the factors of production. The mechanism through which this occurs is our next topic.

This is the crucial point. The analysis belongs to the class of models that consider that business cycle fluctuations occur because the supplies of input vary as their owners (including workers) make optimising adjustments to the quantities they are prepared to supply. These fluctuations occur around the “natural rate of output” or “natural rate of unemployment” (the two concepts are linked via technology).

Only technology and population matter in the long-run and government spending cannot alter short-run variations in output. Ultimately, the economy sits on its long-run growth path which is invariant to government policy.

Elmendorf and Mankiw us the standard national accounting identities to make their case. So they say that national income (Y) is from the perspective of the households either consumed (C), saved (S) or taxed (T):

Y = C + S + T .

National income (output) is equal to aggregate demand (expenditure):

Y = C + I + G + NX

where I is domestic investment, G is government purchases of goods and services, and NX is net exports of goods and services.

Combining these accounting identities and re-arranging them, provides us with the familiar sectoral balances:

S + (T-G) = I + NX .

Which says that private saving (S) plus the government surplus (T-G) equals investment plus net exports.

Elmendorf and Mankiw call (T-G) public saving but that is an erroneous description of the monetary implications of a sovereign government running a budget surplus.

When individuals (households) save they postpone current consumption because they want to have higher future consumption. Saving is a time machine for non-government entities to allow them to transfer consumption across time. The obvious motivation is that they face a budget constraint – as users of the currency – and have to forgoe consumption now if they want to save.

For the monopoly issuer of the currency – the sovereign government – there is no such financial constraint on spending. It does not have to forgoe spending now to spend in the future. It can always spend what it desires at any point in time irrespective of what it did last period or any previous periods.

Further, when the government runs a budget surplus the purchasing power it extracts from the non-government sector doesn’t go anywhere – it is not stored in any account to use for later purposes. Just as a budget deficit (excess of spending over tax revenue) creates net financial assets (in the currency of issue) a budget surplus destroys net financial assets.

There is no store of purchasing power when the government runs a surplus nor does it make any sense for a government to think in those terms. It can always spend what it likes.

So it is nonsensical to characterise a budget surplus as being “saving”. It is more correctly described as the destruction of non-government purchasing power the non-government net financial assets.

But the sectoral flow equation is sound as written.

Elmendorf and Mankiw then correctly point out that:

… a nation’s current account balance must equal the negative of its capital account balance.

So net exports equals net foreign investment, or NFI, “which is investment by domestic residents in other countries less domestic investment undertaken by foreign residents”:

NX = NFI

This just means that the “international flows of goods and services must be matched by international flows of funds”. This equality is however subject to interpretation and the mainstream paradigm constructs it as meaning that nations with current account deficits (CAD) are living beyond their means and are being bailed out by foreign savings.

From an MMT perspective, a CAD can only occur if the foreign sector desires to accumulate financial (or other) assets denominated in the currency of issue of the country with the CAD.

This desire leads the foreign country (whichever it is) to deprive their own citizens of the use of their own resources (goods and services) and net ship them to the country that has the CAD, which, in turn, enjoys a net benefit (imports greater than exports). A CAD means that real benefits (imports) exceed real costs (exports) for the nation in question.

So the CAD signifies the willingness of the citizens to “finance” the local currency saving desires of the foreign sector. MMT thus turns the mainstream logic (foreigners finance our CAD) on its head in recognition of the true nature of exports and imports.

Subsequently, a CAD will persist (expand and contract) as long as the foreign sector desires to accumulate local currency-denominated assets. When they lose that desire, the CAD gets squeezed down to zero. This might be painful to a nation that has grown accustomed to enjoying the excess of imports over exports. It might also happen relatively quickly. But while the situation lasts the importing nation is getting real benefits and should enjoy them.

Please read my blog – Modern monetary theory in an open economy – for more discussion on this point.

The standard procedure is then to substitute the NX = NFI into the previous sectoral balance expression S + (T-G) = I + NX to get:

S + (T-G) = I + NFI

which they say:

… shows national saving as the sum of private and public saving, and the right side shows the uses of these saved funds for investment at home and abroad. This identity can be viewed as describing the two sides in the market for loanable funds.

Note the comments above about the erroneous contruction of public saving.

MMT constructs this version of the sectoral balances as saying for national income to be unchanged the leakages from the spending system [left-hand side => S + (T-G)] have to be equal to the injections [right-hand side => I + NFI]. If the actual leakages in any period exceed the injections then income will fall to bring the relationship back into equality. I could go on about this at length but haven’t the time today.

But more importantly, once Elmendorf and Mankiw introduce the loanable funds model to explain why budget deficits drive up interest rates you know they are entering the land of myths.

They motivate their discussion of the previous identity in this way:

Now suppose that the government holds spending constant and reduces tax revenue, thereby creating a budget deficit and decreasing public saving. This identity may continue to be satisfied in several complementary ways: Private saving may rise, domestic investment may decline, and net foreign investment may decline.

They claim that “private saving rises by less than public saving falls” which means that “total investment–at home and abroad–must decline as well”.

The fall in investment reduces the capital stock (reducing income and output) and increasing the interest rate. Why? Answer: according to the marginal productivity theory (MPT) the lower capital stock means the smaller stock of capital is now more productive and so the rate of return rises which forces all interest rates up as well as pushing real wages down.

Further, because they claim there is a “decline in net foreign investment” this requires a “decline in net exports” and a rising budget current account deficit – and so they think they substantiate the “twin deficits” argument. Please read my blog – Twin deficits – another mainstream myth – for more discussion on this point.

None of this is remotely what happens.

In terms of the above model [S + (T-G) = I + NFI], MMT suggests that as (T-G) falls (net public spending rises), national income rises which also stimulates saving (S). Further, it may increase imports which may reduce NX but in that situation the exchange rate pressure will increase international competitiveness and stimulate exports (X) and attract foreign investors (NFI).

The rising activity will also stimulate investment (I) as firms sense improved opportunities to realise profits by expanding capacity (this is known as the accelerator effect in the literature). With the central bank in charge of interest rates, the budget deficit “crowds-in” private spending.

So where do the mainstream economists go wrong? At the heart of this conception is the theory of loanable funds, which is a aggregate construction of the way financial markets are meant to work in mainstream macroeconomic thinking. The original conception was designed to explain how aggregate demand could never fall short of aggregate supply because interest rate adjustments would always bring investment and saving into equality.

In Mankiw’s macroeconomics textbook, which is representative, we are taken back in time, to the theories that were prevalent before being destroyed by the intellectual advances provided in Keynes’ General Theory.

Mankiw assumes that it is reasonable to represent the financial system as the “market for loanable funds” where “all savers go to this market to deposit their savings, and all borrowers go to this market to get their loans. In this market, there is one interest rate, which is both the return to saving and the cost of borrowing.”

This is back in the pre-Keynesian world of the loanable funds doctrine (first developed by Wicksell).

This doctrine was a central part of the so-called classical model where perfectly flexible prices delivered self-adjusting, market-clearing aggregate markets at all times. If consumption fell, then saving would rise and this would not lead to an oversupply of goods because investment (capital goods production) would rise in proportion with saving.

So while the composition of output might change (workers would be shifted between the consumption goods sector to the capital goods sector), a full employment equilibrium was always maintained as long as price flexibility was not impeded. The interest rate became the vehicle to mediate saving and investment to ensure that there was never any gluts.

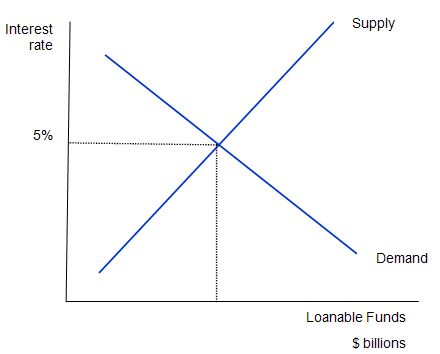

The following diagram shows the market for loanable funds. The current real interest rate that balances supply (saving) and demand (investment) is 5 per cent (the equilibrium rate). The supply of funds comes from those people who have some extra income they want to save and lend out. The demand for funds comes from households and firms who wish to borrow to invest (houses, factories, equipment etc). The interest rate is the price of the loan and the return on savings and thus the supply and demand curves (lines) take the shape they do.

Note that the entire analysis is in real terms with the real interest rate equal to the nominal rate minus the inflation rate. This is because inflation “erodes the value of money” which has different consequences for savers and investors.

Mankiw claims that this “market works much like other markets in the economy” and thus argues that (p. 551):

The adjustment of the interest rate to the equilibrium occurs for the usual reasons. If the interest rate were lower than the equilibrium level, the quantity of loanable funds supplied would be less than the quantity of loanable funds demanded. The resulting shortage … would encourage lenders to raise the interest rate they charge.

The converse then follows if the interest rate is above the equilibrium.

Mankiw also says that the “supply of loanable funds comes from national saving including both private saving and public saving.” Think about that for a moment. Clearly private saving is stockpiled in financial assets somewhere in the system – maybe it remains in bank deposits maybe not. But it can be drawn down at some future point for consumption purposes.

Mankiw thinks that budget surpluses are akin to this. As noted above – budget surpluses are not even remotely like private saving. You should clearly understand by now that budget surpluses destroy liquidity in the non-government sector (by destroying net financial assets held by that sector). They squeeze the capacity of the non-government sector to spend and save. If there are no other behavioural changes in the economy to accompany the pursuit of budget surpluses, then as we will explain soon, income adjustments (as aggregate demand falls) wipe out non-government saving.

So this conception of a loanable funds market bears no relation to “any other market in the economy” despite the myths that Mankiw uses to brainwash the students who use the book and sit in the lectures.

Also reflect on the way the banking system operates. The idea that banks sit there waiting for savers and then once they have their savings as deposits they then lend to investors is not even remotely like the way the banking system works.

Please read the following blogs – Money multiplier and other myths – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for further discussion.

This framework is then used to analyse fiscal policy impacts and the alleged negative consquences of budget deficits – the so-called financial crowding out – is derived.

In relation to the diagram above, Mankiw asks: “which curve shifts when the budget deficit rises?”

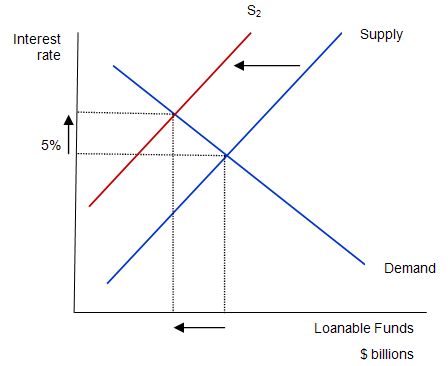

Consider the next diagram, which is used to answer this question. The mainstream paradigm argue that the supply curve shifts to S2.

Why does that happen? The twisted logic is as follows: national saving is the source of loanable funds and is composed (allegedly) of the sum of private and public saving. A rising budget deficit reduces public saving and available national saving. The budget deficit doesn’t influence the demand for funds (allegedly) so that line remains unchanged.

The claimed impacts are: (a) “A budget deficit decreases the supply of loanable funds”; (b) “… which raises the interest rate”; (c) “… and reduces the equilibrium quantity of loanable funds”.

Mankiw says that:

The fall in investment because of the government borrowing is called crowding out …That is, when the government borrows to finance its budget deficit, it crowds out private borrowers who are trying to finance investment. Thus, the most basic lesson about budget deficits … When the government reduces national saving by running a budget deficit, the interest rate rises, and investment falls. Because investment is important for long-run economic growth, government budget deficits reduce the economy’s growth rate.

The analysis relies on layers of myths which have permeated the public space to become almost “self-evident truths”. Obviously, national governments are not revenue-constrained so their borrowing is for other reasons – we have discussed this at length. This trilogy of blogs will help you understand this if you are new to my blog – Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 | Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 | Deficit spending 101 – Part 3.

But governments do borrow – for stupid ideological reasons and to facilitate central bank operations – so doesn’t this increase the claim on saving and reduce the “loanable funds” available for investors? Does the competition for saving push up the interest rates?

Answer: No and no!

But we need to be careful. MMT does not claim that central bank interest rate hikes are not possible. It is possible that a poorly managed central bank will interpret a rising budget deficit as being inflationary and push up interest rates. There is also the possibility that rising interest rates reduce aggregate demand via the balance between expectations of future returns on investments and the cost of implementing the projects being changed by the rising interest rates.

MMT proposes that the demand impact of interest rate rises are unclear and may not even be negative depending on rather complex distributional factors. Remember that rising interest rates represent both a cost and a benefit depending on which side of the equation you are on. Interest rate changes also influence aggregate demand – if at all – in an indirect fashion whereas government spending injects spending immediately into the economy.

But having said that, the Classical claims about crowding out are not based on any of these mechanisms. In fact, they assume that savings are finite and the government spending is financially constrained which means it has to seek “funding” in order to progress their fiscal plans. The result competition for the “finite” saving pool drives interest rates up and damages private spending. This is what is taught under the heading “financial crowding out”.

A related theory which is taught under the banner of IS-LM theory (in macroeconomic textbooks) assumes that the central bank can exogenously set the money supply. Then the rising income from the deficit spending pushes up money demand and this squeezes interest rates up to clear the money market. This is the Bastard Keynesian approach to financial crowding out. Please read my blog – Those bad Keynesians are to blame – for more discussion on this point.

Neither theory is remotely correct and is not related to the fact that central banks push up interest rates up because they believe they should be fighting inflation and interest rate rises stifle aggregate demand.

So the Elmendorf and Mankiw claim is summarised like this (from the Australian Treasury paper):

… a budget deficit reduces national saving, which implies a shortage of funds to finance investment. This would place upward pressure on interest rates as firms compete to finance their investments from the existing pool of domestic saving.

But from a macroeconomic flow of funds perspective, the funds (net financial assets in the form of reserves) that are the source of the capacity to purchase the public debt in the first place come from net government spending. Its what astute financial market players call “a wash”. The funds used to buy the government bonds come from the government!

There is also no finite pool of saving that is competed for. Loans create deposits so any credit-worthy customer can typically get funds. Reserves to support these loans are added later – that is, loans are never constrained in an aggregate sense by a “lack of reserves”. The funds to buy government bonds come from government spending! There is just an exchange of bank reserves for bonds – no net change in financial assets involved. Saving grows with income.

But importantly, deficit spending generates income growth which generates higher saving. It is this way that MMT shows that deficit spending supports or “finances” private saving not the other way around.

The Australian Treasury paper also notes that “a budget deficit may not reduce the domestic capital stock as the adjustment can occur through higher capital inflows – which may not necessarily change interest rates”. Pretty basic really even without the extra MMT insights in the preceding paragraphs.

In discussing the conventional view, Elmendorf and Mankiw offer the parable of the debt fairy to compute the “crowding out of capital” effects? They ask us to:

Imagine that one night a debt fairy (a cousin of the celebrated tooth fairy) were to travel around the economy and replaced every government bond with a piece of capital of equivalent value. How different would the economy be the next morning when everyone woke up?

How cute! A debt fairy who can just alter the maximising decisions of the private sector overnight and force portfolio choices upon that same sector that presumably do not correspond with the profit-seeking circumstances that prevailed when the investors eschewed the decision to accumulate physical capital and invested in bonds instead.

The debt fairy in fact has no application to the modern monetary system. The

Had they invested in physical capital the public deficit would have been lower anyway and the debt-issued lower.

But even they have to admit that this construction is erroneous (you can read why if you are interested).

The Australian Treasury paper acknowledges that the state of mainstream theory is such that:

the theoretical ambiguities about the connection between debt and interest rates … [provide no robust conclusions].

That is, the mainstream theoretical literature is so dependent on extreme assumptions and total falsehoods about the way the real world monetary system operates that the major conclusions are without theoretical authority

Most of the results in the mainstream literature require extreme assumptions to derive the main conclusions. Even within the logic of their own flawed models if you relax one of these key assumptions the whole analytical edifice collapses and the conclusions are no longer supported by the theory.

Virtually none of the assumptions that underpin the key mainstream models relating to the conduct of government and the monetary system hold in the real world. This means that the mainstream macroeconomic conclusions cannot be typically based on the theoretical models. At that point they become ideological.

In terms of the New Keynesian models which drive the Elmendorf and Mankiw reasoning and now represent the “conventional” view of monetary systems, the claimed theoretical robustness of their models always give way to empirical fixes in response to anomalies.

This general ad hoc approach to empirical anomaly cripples the mainstream macroeconomic models and strains their credibility. When confronted with increasing empirical failures, the mainstream economists introduce these ad hoc amendments to the specifications to make them more realistic. I could provide countless examples which include studies of habit formation in consumption behaviour; contrived variations to investment behaviour such as time-to-build , capital adjustment costs or credit rationing.

Further, the New Keynesian authors (like Mankiw et al) appear unable to grasp is that these ad hoc additions, which aim to fill the gaping empirical cracks in their models, also compromise the underlying rigour provided by the assumptions of intertemporal optimisation and rational expectations. At least, they never admit to this and leave the unsuspecting (usually uncritical) reader thinking that the conclusions are valid.

Please read my blog – Mainstream macroeconomic fads – just a waste of time – for more discussion on this point.

Next time you hear a politician or some conservative start raving about crowding out ask them a few questions:

1. Why are you assuming the pool of domestic saving and/or foreign saving is finite?

2. Don’t banks lend to credit-worthy customers?

3. Where did the funds the government borrows come from?

4. Why have interest rates been around zero and long-term yields not much higher in Japan for two decades despite rising budget deficits?

See their eyes roll and enjoy the moment?

Australian Treasury Paper results

Anyway, the Australian Treasury Paper cites a number of empirical studies that “find” that rising deficits drive up interest rates. I know all of the papers cited well and each one is deeply flawed in both conception or empirical application. None of them hold water.

I won’t describe the econometric method the Paper employs but it is standard and the results are not biased one way or another by the choice of estimation technique. We could quibble about some technical matters but it would be “chess playing” rather than a constituting a substantive attack on the results.

The Australian Treasury Paper concludes that:

… in the long run, the real interest margin rises by around three basis points in response to a one percentage point of GDP increase in the stock of Australian general government net debt … In the short run, however, Australian fiscal variables do not have a statistically significant impact on the interest margin. Importantly, the results indicate that a number of US economic variables, namely inflation and the current account, exert the most powerful influence on the real interest margin.

So domestic budget deficits do not drive up interest rates. The long-run effect (a stylised econometric state!) is virtually zero. The short-run effect is zero!

Zero means nothing – no relationship – go away!

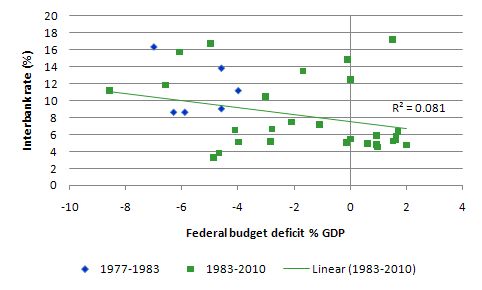

I posted the following graph in an earlier blog – Twin deficits – another mainstream myth – but it is worth repeating. It is based on Reserve Bank of Australia data and shows the relationship between the federal budget deficit and the overnight interest rate from 1977 to now. The different colours indicate the period before (blue) and after (green) the exchange rate was floated.

You will appreciate clearly – there is no relationship. This graph could be reproduced for the advanced world and you wouldn’t find a robust relationship. So that avenue for the TDH is missing.

The Australian Treasury Paper used advanced econometric analysis to find the same thing. Good on them but they could have just looked at this graph and reflected on the way the monetary system operates to reach the same conclusion. I am happy though that they have jobs and are free from the ravages of unemployment!

In his Melbourne Age article last week (September 18, 2010) – Treasury backflip on deficit link – economic correspondent Tim Colebatch describes the Australian Treasury Paper as providing:

… a stunning backflip from Treasury’s earlier views … [which] … challenges a large body of work by other economists that find a strong link between fiscal policy and interest rates.

Conclusion

Lets hope that within Australian macroeconomic policy circles, at least, this insight becomes the norm.

Also all you macroeconomics teachers and lecturers out there – toss out your Mankiw textbooks and start teaching your students something that is closer to the truth. Otherwise, you should resign.

That is enough for today!

I have made the same arguments against crowding out arguments made at the State government level.

The logic used by Mankiw is very twisted indeed.

I have seen other public finance textbooks that describe public sector borrowing as increasing the demand for funds (private savings), and thereby increasing interest rates, but not reducing the quantity of “loanable funds”. Basically the x axis in these models is “quantity of funds” rather than ‘loanable funds”- which does not imply a finite supply of savings like Mankiw does.

Of course these arguments make assumptions about the elasticity of supply of loanable funds. If suply is highly elastic (i.e. you are an open economy, and there are lots of Chinese/ Germans willing to make you loans for worthwhile projects at the prevailing interest rate) you should also expect no crowding out from increased government debt.

This is picked up by your points that:

“1. Why are you assuming the pool of domestic saving and/or foreign saving is finite?

2. Don’t banks lend to credit-worthy customers?

3. Where did the funds the government borrows come from?

4. Why have interest rates been around zero and long-term yields not much higher in Japan for two decades despite rising budget deficits?”

So my conclusion is that MMT type views about public debt and deficits are becoming more widely held in Australian policy circles at both a state and Federal level- and the paper cited proves this.

it seems pretty self evident to me that the move to a budget deficit causes interest rates to fall, not rise. the private sector have more money in their hands, so less demand for and greater supply of loanable funds – thereby putting downward pressure on interest rates. conversely, by stripping money from the private sector, budget surpluses cause greater private sector demand for debt to satisfy aggregate demand – so pushing up interest rates.

in the case of a budget deficit, a government might feel the need to offset falling interest rates by issuing debt – so debt issuance intentionally tries to raise interest rates. it seems strange to me that the mainstream autistics argue the opposite of this position when it fits so neatly with their silly demand and supply pictures.

but it also occurs to me that the recent popularity of sovereign wealth funds as dumping grounds for surpluses, like the future fund, suggest that budget “surpluses” don’t kill private sector purchasing power, they just shift purchasing power from those most in need of government services (eg the unemployed) to the bankers and other benefactors of public investment in domestic and foreign equity markets… budget surpluses and the whole neoliberal paradigm just smacks of institutional corruption.

It is quite possible for households to using their saving to pay down gross debt (there are numerous ways to accommodate this in sector balances terms), just as is possible for governments to use their saving to pay down gross debt. In both cases it is saving and it is a surplus. In neither of these cases is saving stored – in both cases it goes “nowhere”. Households can also spend whatever they like within their assigned bank credit limits – and they spend by crediting bank accounts as well.

The difference between government and household finance is not one of substance (in the nature of saving or spending), but of degree. Households have credit limits imposed by others. Governments have credit limits that are either self-imposed or effectively non-existent.

As you describe it, the mistake made by Mankiw in his interpretation of the Sectoral Balance equation seems to hinge on treating a dynamic relationship in a static manner. That is, he lowers (T-G) but holds S constant, whereas MMT claims that T-G going negative would necessarily produce a positive change in S. Have I got that right?

I am very interested in the sectoral balances issue and basically understand it, for someone who is math-and-equation-challenged. I don’t always understand which way the various sectors have to go, positive or negative, to balance the others. Assume a situation where , as now in the U.S., we have, and will continue to have for a while, a current account deficit and a yearly fiscal deficit. If the deficit hawks had their way and we moved somehow to a balanced budget, assuming the CAD stayed the same, how would domestic savings/investment have to change to support that?

As in the 9/18 quiz:

“When an external deficit and public deficit coincide, there must be a private sector deficit. This suggests that governments can only run budget deficits safely to support a private sector surplus, when net exports are strong.” ANS: “So the answer is false because the coexistence of a budget deficit (adding to aggregate demand) and an external deficit (draining aggregate demand) does have to lead to the private domestic sector being in deficit.” AND ” With the external balance set at a 2 per cent of GDP, as the budget moves into larger deficit, the private domestic balance approaches balance (Case B). Then once the budget deficit is large enough (3 per cent of GDP) to offset the demand-draining external deficit (2 per cent of GDP) the private domestic sector can save overall (Case C).”

Hmm, I am understanding it more just typing this, but I am having trouble distinguishing between savings and investment: “The budget deficits are underpinning spending and allowing income growth to be sufficient to generate savings greater than investment in the private domestic sector….” Why is it seemingly that domestic savings and investment offset each other where to me it would seem they would add to the domestic sectoral balance.

This phrase the “private domestic sector being in deficit” means people saving? Like a savings rate of 3%, or by “deficit” is it meant people spending more than they earn?

It is possible that a poorly managed central bank will interpret a rising budget deficit as being inflationary and push up interest rates.

Unfortunately calling it possible is a huge understatement. Budget deficits do cause inflation (and hence interest rates) to be higher than they would otherwise be.

Unless you think that any central bank with an inflation targetting policy is by definition poorly managed, it is also probable that a well managed central bank would come to that conclusion. There may be an exception during a recession, but the Australian economy’s well past that stage now. And the effect is likely to be confined to the short term, but that doesn’t mean it can be ignored.

Is economics the only “science” that doesn’t care about empirical results? Actually, they care in that they can reinterpret results to fit which ever model they happen to be interested in.

The RBA paper “examines the empirical relationship between government debt and the real interest margin between Australian and US 10-year government bond yields.”

The fact that they found no relationship between between REAL interest rates and deficits does not mean there is no relationship between NOMINAL interest rates and deficits.

Most savers and borrowers face NOMINAL interest rates.

As Aidan mentioned above, persistent budget deficits can cause inflation, which leads to higher nominal interest rates.

If interest rates went up to 15% I don’t think many people would gain much comfort if you told them: “Don’t worry mate, inflation is running at 13%, you’re still only paying 2% real interest on your mortgage.”

anon – if you think that something being self-imposed vs. externally-imposed is not a difference of substance, then I believe you are on the wrong blog.

“As Aidan mentioned above, persistent budget deficits can cause inflation, which leads to higher nominal interest rates.”

Surely only if interest rates are used to deal with inflation.

Persistent budget deficits are there to deal with persistent surpluses elsewhere in the identity. Once those surpluses stop being persistent then the deficit needs to stop as well.

The challenge is to design a counter cyclical policy structure that the politicians can operate without subverting it. One of the beauties of Job Guarantee vs. Warren’s tax cut proposal is that the cost of the Job Guarantee is determined by private sector activity. The only political involvement is to set the level of the minimum wage.

Tax cuts however have to become tax rises at some point if they are to behave counter cyclically. That is politically difficult to do.

Anon – How can a federal government who issues its own currency save in that same currency?

It cannot. It can only spend.

pebird,

I fully agree with anon.

anon,

“. . . and they spend by crediting bank accounts as well.”

Remember about the discussion about Gold Standard and crediting bank accounts? Now one more: the People’s Bank of China has an account at the Fed and let us say that it needs to make some payment. It also spends by crediting bank accounts – just like the US Treasury.

Excellent, Ramanan.

The dynamics whereby a household spends using its commercial bank are not essentially different than the dynamics whereby a government spends using its central bank. Both types of spending result in the crediting of bank accounts. As noted, the difference is one of degree in the level of credit limits or borrowing limits in each case.

The ironic thing is that households are less constrained using commercial bank credit to spend (e.g. credit card limits) than governments are in using central bank credit to spend (only in the MMT counterfactual of no bonds).

And more ironic for pebird – the difference between the actual bank credit arrangements for households and the self-imposed bond borrowing requirements for governments is a difference of substance when it comes to characterizing the actual availability of the bank credit channel for these different borrowers.

Making progress.

Ramanan,

It’s a hell of a thing spending by crediting bank accounts …

… we all spend by crediting bank accounts …

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3zKCIf-vfbc

Does the loanable funds doctrine assume a 100% capital requirement?

“… we all spend by crediting bank accounts …”

Does that make people vulnerable to a “currency tax”?

Bill,

Do you know this book:

E. J. Nell, and M. Forstater, Reinventing Functional Finance: Transformational Growth and Full Employment, Edward Elgar, Northampton, Mass., Cheltenham, 2003.

Any thoughts on it? Do you agree with its version of MMT?

Regards

Frank,

Glad to see you here. You will get more precise answers and less disruption here than at the other forum.

I can answer this question:

“This phrase the “private domestic sector being in deficit” means people saving? Like a savings rate of 3%, or by “deficit” is it meant people spending more than they earn?”

This means the latter: people spending more than their income.

I can’t spend by crediting my bank account. I have to make a deposit and then the bank credits my account in that amount and only in that amount. If the deposit is a check drawn on another bank, it may take the bank some days to get around to crediting my account, during which time I do not have access to the funds. What on earth are you talking about?

anon says:

Wednesday, September 22, 2010 at 22:05

I think the contention to your comment comes from definition of government saving in the sentence. “just as is possible for governments to use their saving to pay down gross debt.” Do you mean Bill’s or Mankiw’s definition?

Aidan says:

Wednesday, September 22, 2010 at 23:30

“Unfortunately calling it possible is a huge understatement. Budget deficits do cause inflation (and hence interest rates) to be higher than they would otherwise be.”

There are different types of inflationary inbalance (e.g. supply shock/ excess wage inflation). Wouldn’t a targetted response be required depending on the root cause? I think issues arise from the blunt instrument of interest rates and misintepretation of the signals.

The only fact I am sure about. The application of current economic theory is wrong. Either the theories are wrong or it is being twisted for erroneous purpose.

Why can we NOT have a stable predictable economy. When companies analyse WW demand for commonly used MNC products. At an aggregate level, demand is relatively stable. Changes in aggregate demand are small and take a long time to materialise. Well managed companies are rarely surprised and have plenty of time to respond to changes in economic trajectory. Capital investments and factory size are regularly reviewed and tweaked to manage excess capacity. It is not difficult science and it is generally managed efficiently.

I refuse to believe the whole economy is uncontrollable and unstable when aggregate human behaviour is so predictable and consistent.

My No1 suspect: The science of economic measurement and control is fundamentally flawed.

Tom Hickey:

“I can’t spend by crediting my bank account.”

“Yes, you can !”

Everyone spends by crediting one’s bank account — there is no other way to spend.

Dear Andrew (at 2010/09/23 at 11:36)

You will discover that I have a chapter in that book on the open economy. I agree with most but not all the contributions that are in that book of readings.

best wishes

bill

“Crediting bank accounts” as I understand the way that MMT’ers use the phase implies increasing financial assets. Only the government and banks as public/private partnerships can do this, and only government can increase net financial assets. Only they have access to the spreadsheets that do the markup. My keyboard is not hooked into that loop (FRS). Is yours? If it is, please tell me how to do it.

Bill,

I’ll give it a look one day.

First, I have to check if my budget is constrained. 😉

Gamma: If not, then there would be nothing preventing a government from funding all spending through currency issuance and not levying any taxes. This would obviously produce rampant inflation. I am not saying MMT is advocating this, but what would prevent this from happening?

MMT (functional finance aspect) does recommend funding all spending through currency issuance and not levying taxes to close an output gap through fiscal policy should a very severe gap develop (like now in the US and UK). Then as the gap closes, as indicated by approaching full employment, taxes would be reinstated and spending reduced in order so as to establish full employment/optimal utilization along with price stability. That is the basic idea of functional finance.

Inflation (general price increase over time) only occurs when effective demand outpaces the capacity of the economy to meet demand with supply. Before this occurs, taxes are applied to withdraw nongovernment net financial assets to quell demand and reduce the inflationary pressure.

The government requires the services of a bank in order to participate in the payments system. The government’s payments do not clear against a cookie jar sitting next to the Speaker of the House.

The government’s bank is the central bank.

When the government “spends by crediting bank accounts”, it means that its payments will clear back to its account at the central bank. The government is using the services of the central bank in doing so. That is operational reality, not cookie jar fantasy.

Households also spend by crediting bank accounts. One example is credit card spending. I use my commercial bank in the same way the government uses its central bank. My expenditure by credit card is effectively an instruction to credit the bank account of the expenditure recipient. The spending clears back to my credit card balance with my bank.

Another example is preauthorized debit. My expenditure again is an instruction to credit the bank account of the expenditure recipient. The spending clears back as a debit to my deposit balance with my bank.

And so on. The analogy is clear. Both the government and I require the services of a bank to participate in the payments system. We both spend by crediting bank accounts, using our respective banks in the process of clearing those payments.

The analogy has nothing whatsoever to do with the subject of net financial assets per se. But that subject can be analogized as well. When I spend, I create net financial assets for the rest of the world, where the rest of the world is defined as all balance sheets except mine. Work it through. When I spend by using my credit card limit, that’s exactly what I’m doing. I’m increasing my own net financial liabilities, while increasing net financial assets for the rest of the world. So that analogy works as well.

Again, the difference between governments and households is one of degree, not of substance, insofar as the payments process and balance sheets and constraints are concerned, and the way these things are usually discussed in MMT. The degree reflects the difference in the operation of credit limits, as noted above.

In the prevailing system, there IS a substantial difference between the availability of bank credit to a household and the restriction on governments to borrowing bonds. But that difference is in the reverse orientation to what is usually presumed in MMT. That difference is more constraining on governments than it is on households. It can be neutralized by invoking no bonds.

anon:

“When I spend, I create net financial assets for the rest of the world, where the rest of the world is defined as all balance sheets except mine”

But your balance sheet can run out because you cannot “print” money. The government always has this option – it’s asset column is infinity. That’s the substantial difference.

The central bank, as Bill often states, is part of the government. It’s not a private corporation – it’s administered by government appointed officials. It’s independence is a smokescreen.

The fact that you can make tortured analogies between governments and households do not make them equivalent.

anon, when households spend by creating credit in sellers bank account they also create an equivalent (or larger) debt in their own account. Because the central bank is part of government and fiat money production is a government monopoly, the government is under no obligation to create an equivalent debt to its spending. Currently they do, out of fear of inflation; but this is a self-imposed policy, not an external imposition as is the demand that households pay their credit card bills. Governments can’t be forclosed upon or faced with debt collectors if they fail to act on the debt the way households can. I think that’s the difference between chartalist (MMT) and circuitist ideas that you aren’t grasping.

I was just doing a 5 min bit of research on Argentina.

From the data in Wikipedia. The last few years they have been having inflation % in the mid teens with interest rates in the mid to high teens. Official unemployment % is in high single digits. I believe (but did not confirm) that they run a persistent spending deficit.

While I fully applaud their increases in employment and per capita income. Personally I find it difficult to envisage persistent (stable?) inflation of 15% per anum. Can anyone tell me what is going on. Is this MMT at work? I understand Warren Mosler and Bill have done work in South America.

If MMT is implemented today in say Australia or UK, would we expect to see persistant inflation as high as 15%. Frankly, that frightens me and would not be an obvious vote winner. Using Argentina as a selling point would be a hard sell to any layman.

A bit more lazy research and maybe I can answer my own question.

http://en.mercopress.com/2010/08/19/argentine-economic-activity-expands-11.1-in-june-over-a-year-ago

So Argentina also enjoys stellar growth. High inflation is a respectable trade off. It must be hard to manage pay administration.

Mrs. Kirchner is right up there with Christine O’Donell too. That’s some Country!

Ok folks- with this whole ‘deficits cause inflation’ non-sense, MMT, as far as I can see, never said that deficits can’t cause inflation. In fact, it specifically states REAL RESOURCES is what matters i.e. nominal demand exceeding available supply. The issue is not a FINANCIAL issue at all. The issue here is shifting our language away from the latter, and toward the former. It also takes the view deficits, although not always, for the most part are endogenous driven.

By this measure, we aren’t headed with an inflationary orgy. Contrast the 1970s with today:

* 1970s private debt was no where near as high as it is today; any deficit spending today will probably go toward paying off private sector debt and thus inflation would hardly be an issue – this is partly what explains why the hell happened in Japan.

* Capacity utilisation in the 1970s was far higher (in fact, shortly before the 1973 and 82 recession it hit 91% and 83%); not an issue today (capacity utilisation is far lower)

* no oil shocks or huge supply side shocks as of yet

* transfer payments as a % increase were far more rapid

It is true deficits may lead to NOMINAL increases in interest rates (as they did in the 1973 period as transfer payments exploded), but probably put downward pressure on real interest rates – in any event, businesses/households still accure the cashflows needed to valdiate business debt and as far as I can see as the 1975 budget deficit exploded interest rates were going down…

So the issue in Argentina is this: are there enough REAL resources to go around? They have had quick alot of chronic failures on the supply-side to my understanding.

Tom: I agree with your description of functional finance, but I think you’ve put it in too extreme language, as MMTers often do.

You talk about “funding all spending through currency issuance and not levying taxes….”. Assume for the sake of argument ALL the additional currency issuance is fed straight into the pockets of employees. In a country where government takes about 40% of GDP, the result would be a near doubling of employees’ take home pay. That strikes me as a recipe for chaos.

I’d be comfortable with boosting employees take home pay by 5% or 10%, but not anything approaching 100%.

Anon, Ramanan

when you spend you spend with commercial bank money which is the creature of commercial banks. They create it with their keyboards and full point. Nothing needs to happen elsewhere apart from your expenditure popping up on some other account in the banking system.

When government spends it creates money in the settlement system via crediting account with central bank money (reserves). The expenditure process is accompanied by the conversion of central bank reserves into commercial bank money at the exchange rate 1:1.

It is an enormous difference in substance which money you actually have and spend: private sector liabilities or government liabilities.

“you cannot “print” money”

When I spend by credit card, I am crediting the bank accounts of others by instructing my bank to do so. Using my credit line increases banking system deposits as a result. It is analogous to the effect of government spending on banking system deposits. Both actions have “printed” money in the form of new bank deposits.

“it’s asset column is infinity”

You’re not so bad at tortured descriptions yourself.

“Governments can’t be forclosed upon or faced with debt collectors if they fail to act on the debt the way households can”

Right – I agree with what you’ve said, and nothing there contradicts my main point on operational similiarity.

“When you spend you spend with commercial bank money which is the creature of commercial banks. They create it with their keyboards and full point. Nothing needs to happen elsewhere apart from your expenditure popping up on some other account in the banking system… When government spends it creates money in the settlement system via crediting account with central bank money (reserves). The expenditure process is accompanied by the conversion of central bank reserves into commercial bank money at the exchange rate 1:1.”

Nice point on reserves, but it’s really irrelevant to my point. Both the government and I spend by crediting commercial bank accounts. The fact that the government’s initial liability is the medium of exchange (reserves) and mine is a credit card balance or a mortgage or a consumer loan is not the issue. Moreover, that initial government liability is replaced by a bond unless you’re operating in the counterfactual world, but that’s not relevant here either. The point is that both governments and households spend by crediting bank accounts. Both depend on banking functions and bank payment systems to do so. There is no fundamental operational difference here. Both are capable of creating net financial assets for the rest of the world relative to their own balance sheets in that world. This is operational. And both are currency issuers to the degree that they instruct the crediting of commercial bank deposit accounts using their own banks to do so. Both increase commercial bank deposits, which are effectively the same as the medium of exchange, or currency. The initial intermediating role of reserves and the subsequent role of bonds in the case of the government are analogous to the household liability created when the crediting of bank accounts was instructed.

anon, no, government can spend with freshly printed cash. It does not need banking system to spend. You can not. So you can drop banking system from the economy and it will not change the accounting or operational realities of the private sector.

“government can spend with freshly printed cash”

Here we go again – more MMT argument by counterfactual fantasy.

OK. Let’s suppose the government spends entirely by distributing currency (which right away contradicts the MMT mantra that government spends by crediting bank accounts – but let’s adopt your new rules here).

So the government now spends by distributing currency. If I’ve provided the service to the government, I redeem the currency I’ve received at my commercial bank, for a bank deposit. My bank redeems the currency at the CB for reserves.

Same difference.

The government requires the banking system to the degree I use the banking system.

But now you’re probably going to come back and say that neither of us requires the banking system or its commercial bank deposits – i.e. another step up the counterfactual fantasy ladder.

Tom:

“”Crediting bank accounts” as I understand the way that MMT’ers use the phase implies increasing financial assets. ”

X spends by paying to Y through bank B.

X credits X’s cash account on X’s books.

Y debits Y’s cash account on Y’s books.

B intermediates by debiting X’s account and crediting Y’s account on B’s books.

One spends by crediting and ‘saves’ by debiting one’s cash account (plus Dr/Cr some other account) — bookkeeping 101.

Ralph: I agree with your description of functional finance, but I think you’ve put it in too extreme language, as MMTers often do.

I was just stating the principles, Ralph. Practice would turn out to be different relative to circumstances; fiscal policy can be tightly targeted to incentivizing and disincentivizing flows to accomplish specific goals. But in general, to address inflation FF says to decrease spending and raise taxes, and vice versa for disinflation. Really, in a deflationary environment there is no reason to tax other than to incentivize/disincentivize specific flows. For example, even in a deflationary environment, taxes that disincentivize negative externality would be not repealed under FF.

One spends by crediting and ‘saves’ by debiting one’s cash account (plus Dr/Cr some other account) – bookkeeping 101.

I’m not sure that the MMT economists are using the phrase this way, but I will leave it to them to clarify, since they are the ones using it. But that is not my understanding of what they mean.

Anon, methinks what you are saying boils down to Mitchell-Innes’ insight that the State Theory of Money (Knapp, tax-driven money) can be understood by the Credit Theory of Money. His articles and the book Wray edited on them are great.

Of course, Anon-money is usually good, but unless you are a TBTF Wall Street bankster, you trillion dollar check is worth a little less – to Some Guy like me – than Tim Geithner’s. So Geithner-geld – USGov $ liabilities – is a bit more important in the economy.

That governments are constrained compared to households in “borrowing” – actually asset swapping for the gov – seems either insufficiently described or wrong. What governments are theoretically, initially, solely constrained in is spending, like any check-kiter. They get around it by the power of taxation (forging checks with your signature 😉 ).

I’m not sure that the MMT economists are using the phrase this way, but I will leave it to them to clarify, since they are the ones using it. But that is not my understanding of what they mean.

That would be odd because, as I understand, one of MMT’s claims to glory is consistent accounting. Consistent accounting terminology would be the first step in the right direction one would imagine.

In the above example, substitute the treasury for X, Boeing selling stuff for Y, the feds for B, and you will get the same flow as in household spending. Households are less restricted in ‘crediting’, as anon noticed, because usually they can obtain an automatic loan (overdraft allowance) that the treasury cannot — the treasury balance at the feds has to be such as to make payment settlement possible at all times. According to the current law, the treasury account does no have any overdraft allowance with the Feds.

Currency issuance is a constitutional prerogative of Congress. Congress delegates this to its agencies, the Treasury and Fed. Dollars are created either by printing currency/minting coin or by the Fed creating bank reserves by marking up spread sheets. All dollars come back to this process. Only the Fed has the password that gives access to its spreadsheet. Banks can neither create reserves by marking up spreadsheets nor create physical currency, and neither can the public.

The Treasury credits bank accounts using the reserves the Fed creates for settlement. The Fed can just credit bank accounts and supply the needed reserves for OMO (lending against collateral) and QE (purchases of assets). All other transactions have to clear using existing reserves, since neither banks nor the public have the Fed’s password to its spreadsheet, or if they do, they are in trouble since they are not authorized to use it.

As I understand it, this is what MMT’ers are referring to.

Tom,

I think you will find that MMT, in saying that the government spends by crediting bank accounts, means nearly always that the bank accounts of bank customers are credited.

True, such a credit results in a matching reserve credit as a bank asset, unless/until drained by bond issuance. But the reserve effect is quite secondary to the primary issue of spending by crediting bank accounts. Only a tiny proportion of government spending would be directed to the banks themselves as recipients, in which case the reserve credit is the exclusive credit. But almost all government spending is directed toward crediting non-bank customer accounts first – i.e. increasing commercial bank deposit liabilities.

It is the crediting of commercial bank deposit liabilities that finds its direct analogy in the case of a household who draws on a credit line such as a credit card facility in order to credit the commercial bank account of the non bank expenditure recipient.

Tom,

Perhaps you may think of this as Part II of the “Marshall’s longest” discussion.

My impression is that the discussion there may have served to help consolidate your own thinking re the most constructive role for the “no bonds” idea in the conceptual paradigm for MMT. Perhaps I’m wrong. But if not, there may be other possibilities for further clarification.

Tom Hickey @ Thursday, September 23, 2010 at 13:55

“Inflation (general price increase over time) only occurs when effective demand outpaces the capacity of the economy to meet demand with supply. Before this occurs, taxes are applied to withdraw nongovernment net financial assets to quell demand and reduce the inflationary pressure.”

So how do you measure the “capacity of the economy to meet demand with supply”? Unemployment? Obviously not because virtually all economies experience inflation and unemployment simultaneously. Right now there is high unemployment in many parts of the world, but almost all countries are experiencing positive inflation (apart from a couple of notable exceptions such as Ireland and Japan).

In Australia, unemployment is 5% and inflation is 3%.

So at what level of unemployment or inflation do you re-instate taxation? Or do you have some other measure in mind?

So how do you measure the “capacity of the economy to meet demand with supply”? Unemployment?

As I understand it, this is Bill’s measure. Bill emphasizes that inflation is a general price rise and that is only possible with effective demand in excess of the ability of supply to meet it. Unemployment indicates underutilization of capacity, so the economy can still expand to meet demand. There may be imbalances in various sectors of the economy responsible for price rises in those sectors, but that does not constitute general price elevation. Prices can go up on some things even in a depression due to supply shortages.

Anon: Perhaps you may think of this as Part II of the “Marshall’s longest” discussion.

My impression is that the discussion there may have served to help consolidate your own thinking re the most constructive role for the “no bonds” idea in the conceptual paradigm for MMT. Perhaps I’m wrong. But if not, there may be other possibilities for further clarification.

This is partially the case, I would agree. But I think that the major point needing clarification here is what MMT’ers actually mean by the phrase in question.

I have no doubt that “crediting bank accounts” means crediting deposit accounts in commercial banks. That’s what Treasury does when it disburses funds electronically, or sends checks that get deposited, and it is what happens when the Fed purchases securities for QE. This gets done by government marking up spreadsheets in the FRS for clearance.

All other crediting and debiting of bank accounts is just shuffling money around endogenously. Only government is exogenous, and it influences the endogenous system through its spreadsheet, to which it alone has authorized access. That is the basis of the horizontal-vertical relationship of government and nongovernment financially, and it is what make government the monopoly currency issuer and nongovernment the currency users.

wow, anon, is it really the basis of your argument?!

“Only a tiny proportion of government spending would be directed to the banks themselves as recipients, in which case the reserve credit is the exclusive credit. But almost all government spending is directed toward crediting non-bank customer accounts first – i.e. increasing commercial bank deposit liabilities.”

Be honest with yourself and everybody else here. What you are referring to is the function of the banking system, not government. At the current level of technology there is no reason as to why only banks are allowed to have accounts at the central bank and therefore have access to the payment system. It used to be a valid reason in the past but not any more. But even beyond purely theoretical arguments, local government are allowed to have account at the central bank. Or you consider this tiny?

Tom,

I am a currency issuer using my bank when I draw on my line of credit. I spend using my bank by crediting bank accounts. It’s the same mechanism as the government applies using the central bank.

I am exogenous relative to the rest of the world. I create net financial assets for the rest of the world when I spend using credit.

I have no problem per se with the MMT exo/endo paradigm. I understand it completely.

My point is that it is not the only possible use of such a paradigm. The MMT paradigm and its meaning for the terms exo and endo is strictly a function of choosing to split the world between government and non-government.

I can just as easily apply a split between households and non-households, using a comparable paradigm, as I have just done.

Sergei,

You appear not to understand what government spending means.

It means the government purchases services from non-government.

My point is that the dollar volume of services that government purchases from banks is very small in the context of total government spending. The former are executed by payments that affect only bank reserve accounts; the latter are executed by payments that affect non-bank deposit accounts with banks as well.

I have no doubt that “crediting bank accounts” means crediting deposit accounts in commercial banks.

The phrase is ambiguous without answering the question: crediting by whom ?

X has a cash account on X’s book which corresponds to X’s account at bank B. X may have a cash account under X’s mattress, but that’s irrelevant.

X spends by crediting the cash account on X’s book and instructing bank B to transfer X’s money from X’s account elsewhere. Bank B debits X’s account and credits an account elsewhere..

X receives money from elsewhere. Bank B debits an account elsewhere and credits X’s account. X debits X’s cash account on X’s books.

Rocket science it ain’t.

anon: The MMT paradigm and its meaning for the terms exo and endo is strictly a function of choosing to split the world between government and non-government.

I can just as easily apply a split between households and non-households, using a comparable paradigm, as I have just done.

anon, you lost me here. There is no essential difference between the monopoly currency issuer and currency users? Or am I failing to understand you point? This is the basis of MMT, after all.

VJK, my understanding of the way that MMT’er’s use “crediting banks accounts” implies “crediting bank accounts by marking up spreadsheets.” I have access to neither the FRS spreadsheet, nor to my bank’s spreadsheet. My bank account gets credited by my depositing funds, not by my marking up the spreadsheet myself. When government credits accounts, including its own (Treasury) account, it does so by marking up a spreadsheet at the FRS, excluding the fact that the CIA often uses suitcases full of $100 bills instead. My actions are in no way the same as the government’s. That, I think, is the MMT point in talking about “crediting bank accounts by marking up spreadsheets.”

Tom,

My very original point was – some things that are taken to be a question of substance are better defined as a question of degree.

I can create money in the endogenous system by using my bank to spend from credit. The government therefore is not a monopoly issuer of the currency in that sense. The money I create using my commercial bank is as good as the money that the government creates using the central bank. We both spend “from nothing”, operationally.

The real difference between us is something else.

First, the government is huge and I am small. That’s a big difference in natural spending capacity.

Second, the nature of any constraints on spending is quite different. But contrary to MMT, NEITHER of us is operationally constrained. The government is not unique in this regard. There is nothing operational that prevents me from creating money using my bank anymore than the government using its bank.

The question becomes, what sort of upper bound is otherwise imposed to spending in either case?

In my case, the upper bound is the limit set by my bank, based on credit analysis.

In the case of the government, the (correct) upper bound is the limit set/implied by MMT, based on real economy constraints.

But in neither case is there an operational upper bound. Credit analysis is no more an operational aspect than is the idea of real economy constraints. The upper bound is policy imposed in both cases.

Yes, the government is different. But let’s try and parse why it’s really different.

Tom:

“crediting bank accounts by marking up spreadsheets.” as stated does not make any accounting sense, operational or otherwise.

My bank account gets credited by my depositing funds on your bank books. On your imaginary/real household[quick]book the same cash account is debited (and your revenue account is credited) by your action although perhaps not recorded.

anon, it is different because it is the monopoly issuer of currency, per the US Constitution. It uses the central bank to do this. Banks can create deposits by making loans, they cannot issue currency in the sense of increase nongovernment net financial assets using the central bank. I simply use the currency. I cannot generate new financial assets by making a loan, since I do not have access to the FRS. The loan I make is not against my capital, it is my capital. When I borrow from the bank, I participate in their capacity to create deposits. I cannot create the deposit myself. I don’t have access to their spreadsheet. As VJK implies above, the transactions take place through banks as an intermediary. This is because non-banks like me cannot do this directly.

VJK, this all transpire through bank intermediation because non-banks do not have access to the settlement system where the spreadsheets are marked up.

Tom,

“Banks can create deposits by making loans, they cannot issue currency in the sense of increase nongovernment net financial assets using the central bank.”

Now you’re just pushing words around from MMT phrases.

The government/central bank is a monopoly issuer of its own liabilities.

It’s not a monopoly issuer of the stuff that’s used to credit bank accounts.

It’s not a monopoly issuer of the stuff that’s used to credit bank accounts.

That’s what banks would like to think, but they are public/private partnerships in which government allows them to quasi-create state money. A lot of people think that the state should not permit this fiction at all but rather create all the money itself, holding that money created from bank loans/deposits is just fictitious money and the basis of most financial problems, since they involve excessive leverage. I have not formeda n opinion on this yet, but it is a worthwhile viewpoint to consider.

“I cannot create the deposit myself.”

Neither does the government, without the use of the central bank. The credit that the government creates does not clear back to a cookie jar next to the Speaker of the House. The credit must clear back to the central bank for it to be accepted in the banking system at large.

There’s no difference in the sense that I require my commercial bank; the government requires its central bank.

If you then revert to the “no bonds” operational counterfactual, then the government essentially merges with the central bank. There’s still no difference. It’s the banking function that’s required for the government to spend by crediting bank accounts, the same as it is for me.

“A lot of people think that the state should not permit this fiction at all”

That’s fine if you like. Eliminate commercial banking, nationalize it all, and have everybody bank with the central bank.

That still doesn’t change my point; if anything it strengthens it. Both the government and I can issue currency using our bank – the central bank. I’m on par with the government as far as that’s concerned. We have different credit limits, as I discussed above. But it’s not the government that’s the monopoly issuer using the central bank, because I use the same facility to create money by spending from credit.

There’s no difference in the sense that I require my commercial bank; the government requires its central bank.