I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Michal Kalecki – The Political Aspects of Full Employment

I have been in Sydney today for meetings. I caught an early train and then back again in the afternoon. Trains journeys are great times to read and write and this blog has been written while crossing the countryside (Sydney is nearly 3 hours south of Newcastle by train). The trip is slower than car because the route is still largely based on the first path they devised through the mountains and waterways that lie between the two cities. The curves in places do not permit the train to go faster. The government is promising however a fast train with a much more direct path (up the F3 freeway I guess). Anyway, several readers have asked me whether I am familiar with the 1943 article by Polish economist Michal Kalecki – The Political Aspects of Full Employment. The answer is that I am very familiar with the article and have written about it in my academic work in years past. So I thought I might write a blog about what I think of Kalecki’s argument given that it is often raised by progressives as a case against effective fiscal intervention.

I dealt with Kalecki’s arguments extensively in one of the chapters of my PhD. Also in 1999, I specifically published a peer-reviewed article arguing that the concerns raised by Kalecki about the opposition that the captains of industry would raise if any government tried to maintain full employment are not binding on a modern Job Guarantee scheme. You can read a working paper version of that article for free – The Job Guarantee and inflation control.

The Job Guarantee

To refresh your memories or introduce you as a new reader to the work I have done on the Job Guarantee concept here is a brief summary of its features. Hardened billy blog-types can skip to the next section (as long as you are sure you know all the ins and outs).

The Job Guarantee that I have advocated for many years now is based on a fundamental understanding of the way the modern monetary system operates. While it may be construed as a job creation scheme it is actually a macroeconomic policy device to ensure full employment and price stability is maintained over the private sector business cycle.

Full Employment:

The Government operates a buffer stock of jobs to absorb workers who are unable to find employment in the private sector. The pool expands (declines) when private sector activity declines (expands). The Job Guarantee fulfills this absorption function to minimise the costs associated with the flux of the economy. So the government continuously absorbs into employment, workers displaced from the private sector.

The “buffer stock” employees would be paid the minimum wage, which defines a wage floor for the economy. Government employment and spending automatically increases (decreases) as jobs are lost (gained) in the private sector.

So the Job Guarantee works on the “buffer stock” principle. I first thought of this idea during my fourth year as a student at the University of Melbourne (in the late 1970s). The basis of the policy came to me during a series of lectures on the Wool Floor Price Scheme introduced by the Commonwealth Government of Australia in November 1970.

The scheme was relatively simple and worked by the Government establishing a floor price for wool after hearing submissions from the Wool Council of Australia and the Australian Wool Corporation (AWC). The Government then guaranteed that the price would not fall below that level by using the AWC to purchase stocks of wool in the auction markets if demand was low and selling it if demand was high. So by being prepared to hold “buffer wool stocks” in low demand and release it again in times of high demand the government was able to guarantee incomes for the farmers.

However, with some lateral thinking you can easily see that what the Wool Floor Price Scheme generated was “full employment” for wool! If the Government fixed the price that it was prepared to pay and then was willing to buy all the wool up to that price then you have an equivalent scheme.

This works just the same for labour resources – just unconditionally offer to buy all labour at a stated fixed wage and you create full employment. What should that wage be?

Job Guarantee Wage:

To avoid disturbing private sector wage structure and to ensure the Job Guarantee is consistent with stable inflation, the Job Guarantee wage rate is best set at the minimum wage level. The Job Guarantee wage may be set higher to facilitate an industry policy function. The minimum wage should not be determined by the capacity to pay of the private sector. It should be an expression of the aspiration of the society of the lowest acceptable standard of living. Any private operators who cannot “afford” to pay the minimum should exit the economy.

Social Wage:

The Government would supplements the Job Guarantee earnings with a wide range of social wage expenditures, including adequate levels of public education, health, child care, and access to legal aid. Further, the Job Guarantee policy does not replace conventional use of fiscal policy to achieve social and economic outcomes. In general, the Job Guarantee would be accompanied by higher levels of public sector spending on public goods and infrastructure.

Family Income Supplements:

The Job Guarantee is not based on family-units. Anyone above the legal working age is entitled to receive the benefits of the scheme. I would supplement the Job Guarantee wage with benefits reflecting family structure. In contrast to workfare there will not be pressure applied to single parents to seek employment.

Funding:

The Job Guarantee would be funded by the sovereign government which faces no financial constraints in its own currency. In the context of the current outlays that are being thrown around in national economies, the investment that would be required to introduce a full blown would be rather trivial. It would be operated locally though.

Inflation control:

The Job Guarantee maintains full employment with inflation control. When the level of private sector activity is such that wage-price pressures forms as the precursor to an inflationary episode, the government manipulates fiscal and monetary policy settings (preferably fiscal policy) to reduce the level of private sector demand.

This would see labour being transferred from the inflating sector to the “fixed wage” sector and eventually this would resolve the inflation pressures. Clearly, when unemployment is high this situation will not arise.

But in general, there cannot be inflationary pressures arising from a policy that sees the Government offering a fixed wage to any labour that is unwanted by other employers.

The Job Guarantee involves the Government “buying labour off the bottom” rather than competing in the market for labour. By definition, the unemployed have no market price because there is no market demand for their services. So the Job Guarantee just offers a wage to anyone who wants it.

NAIBER:

In contradistinction with the NAIRU approach to price control which uses unemployed buffer stocks to discipline wage demands by workers and hence maintain inflation stability, the Job Guarantee approach uses the ratio of Job Guarantee employment to total employment which is called the Buffer Employment Ratio (BER) to maintain price stability.

The ratio that results in stable inflation via the redistribution of workers from the inflating private sector to the fixed price Job Guarantee sector is called the Non-Accelerating-Inflation-Buffer Employment Ratio (NAIBER). It is a full employment steady state Job Guarantee level, which is dependent on a range of factors including the path of the economy. Its microeconomic foundations bear no resemblance to those underpinning the neoclassical NAIRU.

It also wouldn’t be worth estimating or targetting. It would be whatever was required to fully employ labour and maintain price stability.

Workfare or Work-for-the-Dole:

Many people think that the Job Guarantee is just Work-for-the-Dole in another guise. The Job Guarantee is, categorically, not a more elaborate form of Workfare. Workfare does not provide secure employment with conditions consistent with norms established in the community with respect to non-wage benefits and the like.

Workfare does not ensure stable living incomes are provided to the workers. Workfare is a program, where the State extracts a contribution from the unemployed for their welfare payments. The State, however, takes no responsibility for the failure of the economy to generate enough jobs. In the Job Guarantee, the state assumes this responsibility and pays workers award conditions for their work. Under the Job Guarantee workers could remain employed for as long as they wanted the work. There would be no compulsion on them to seek private work. They could also choose full-time hours or any fraction thereof.

Training

The Job Guarantee would be integrated into a coherent training framework to allow workers (by their own volition) to choose a variety of training paths while still working in the Job Guarantee. However, if they chose not to undertake further training no pressure would be placed upon them.

Unemployment benefits:

I would abandon the unemployment benefits scheme and free the associated administrative infrastructure for Job Guarantee operations. The concept of mutual obligation from the workers’ side would become straightforward because the receipt of income by the unemployed worker would be conditional on taking a Job Guarantee job.

I would start paying a Job Guarantee wage to anyone who turned up at some designated Government Job Guarantee office even if the office had not organised work for that person yet.

Administration:

For financial reasons explained below, the Job Guarantee would be financed federally with the operational focus being local. Local Government would be an important administrative sphere for the actual operation of the scheme. Local administration and coordination would ensure meaningful, value-adding work was a feature of the Job Guarantee activities.

Type of Jobs:

Surveys of local governments that we have done reveal a myriad of community- and environmentally-based projects that could be completed if Federal funds were forthcoming.

The Job Guarantee workers would contribute in many socially useful activities including urban renewal projects and other environmental and construction schemes (reforestation, sand dune stabilisation, river valley erosion control, and the like), personal assistance to pensioners, and other community schemes.

For example, creative artists could contribute to public education as peripatetic performers. The buffer stock of labour would however be a fluctuating work force (as private sector activity ebbed and flowed). The design of the jobs and functions would have to reflect this. Projects or functions requiring critical mass might face difficulties as the private sector expanded, and it would not be sensible to use only Job Guarantee employees in functions considered essential.

Thus in the creation of Job Guarantee employment, it can be expected that the stock of standard public sector jobs, which is identified with conventional Keynesian fiscal policy, would expand, reflecting the political decision that these were essential activities.

Open Economy Impacts:

The Job Guarantee requires a flexible exchange rate to be effective. A once-off increase in import spending is likely to occur as Job Guarantee workers have higher disposable incomes. The impact would be modest. We would expect any modest depreciation in the exchange rate to improve the contribution of net exports to local employment, given estimates of import and export elasticities found in the literature.

I will come back to open economy issues in a later blog seeing as there has been some consternation from some commentators recently.

Environmental benefits:

The Job Guarantee proposal will assist in changing the composition of final output towards environmentally sustainable activities. These are unlikely to be produced by traditional private sector firms because they have heavy public good components. They are ideal targets for public sector initiative. Future labour market policy must consider the environmental risk-factors associated with economic growth.

Possible threshold effects and imprecise data covering the life-cycle characteristics of natural capital suggest a risk-averse attitude is wise. Indiscriminate (Keynesian) expansion fails in this regard because it does not address the requirements for risk aversion. It is not increased demand per se that is necessary but increased demand in certain areas of activity.

Summing up

The Job Guarantee can provide a government with a policy framework to maintain continuous full employment without putting pressure on the inflation rate.

Does it solve all problems? Answer: Definitely not. It is a safety net buffer stock system only.

The maintenance of full employment – Kalecki and the Captains of Industry

It is easy to show that the introduction of the Job Guarantee and compared the outcomes to a NAIRU economy. However, there are further issues that arise when we consider the maintenance of full employment using the Job Guarantee policy.

While orthodox economists typically attack the Job Guarantee policy for fiscal reasons, economists on the left also challenge its validity and effectiveness. In 1943, Michal Kalecki published the Political Aspects of Full Employment, in the Political Quarterly, which laid out the blueprint for socialist opposition to Keynesian-style employment policy. The criticisms would be equally applicable to a Job Guarantee policy.

Note the references to Kalecki’s 1943 article come from the collection published in 1971 – Michal Kalecki “Political Aspects of Full Employment”, Selected Essays on the Dynamics of the Capitalist Economy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 138-145.

Kalecki’s article begins by defining what he calls the economics of full employment and it is very interesting to re-read it in the light of the present crisis. He adopts what was then the emerging Keynesian position that:

… even in a capitalist system, full employment may be secured by a government spending programme, provided there is in existence adequate plan to employ all existing labour power, and provided adequate supplies of necessary foreign raw-materials may be obtained in exchange for exports.

He says that “(i)f the government undertakes public investment (e.g. builds schools, hospitals, and highways) or subsidizes mass consumption (by family allowances, reduction of indirect taxation, or subsidies to keep down the prices of necessities), and if, moreover, this expenditure is financed by borrowing and not by taxation (which could affect adversely private investment and consumption), the effective demand for goods and services may be increased up to a point where full employment is achieved. Such government expenditure increases employment, be it noted, not only directly but indirectly as well, since the higher incomes caused by it result in a secondary increase in demand for consumer and investment goods.”

Remember he was writing in 1942 and while governments had gone off the gold standard the convertible currency mentality was still firmly in place waiting to be restored in the Post War period by the Bretton Woods agreement.

In a fiat monetary system such as most nations operate within today the reference to government expenditure being “financed” by taxes or debt-issuance is redundant. A sovereign government is never revenue constrained because it is the monopoly issuer of the currency. But Kalecki’s point is that the stimulus works by increasing effective demand (purchasing intentions backed by cash) and so the more public demand can be created the more stimulatory it will be.

He further notes that the expenditure multiplier will magnify that initial spending injection. So pretty straight Keynesian macroeconomics being outlined.

He then goes on to describe how the government gets the funds:

It may be asked where the public will get the money to lend to the government if they do not curtail their investment and consumption. To understand this process it is best, I think, to imagine for a moment that the government pays its suppliers in government securities. The suppliers will, in general, not retain these securities but put them into circulation while buying other goods and services, and so on, until finally these securities will reach persons or firms which retain them as interest-yielding assets. In any period of time the total increase in government securities in the possession (transitory or final) of persons and firms will be equal to the goods and services sold to the government. Thus what the economy lends to the government are goods and services whose production is ‘financed’ by government securities. In reality the government pays for the services, not in securities, but in cash, but it simultaneously issues securities and so drains the cash off; and this is equivalent to the imaginary process described above.

In the language of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), the government just credits bank accounts when it spends (or posts a cheque) and debits them when it taxes. The funds that it borrows (that is, the funds the private sector use to purchase the public debt instruments) come from the government spending. It is a wash. The government spends and then drains the reserves by selling bonds. The private sector do not have to “use up” any holdings of prior savings to purchase the debt.

Of-course, the government spending creates demand which leads to an expansion of output and income. The income growth, in turn, generates extra saving in the economy. In this way, spending brings forth saving.

Kalecki’s imaginary process is totally unnecessary in a modern monetary economy operating a fiat currency system. There is no necessity to drain the reserves that are created by the deficit spending. The government is in fact doing the private sector a favour by issuing debt because it is providing the bond holders with a risk-free (guaranteed) annuity (income stream) which it can always fall back on when speculation in other financial assets is subject to excessive uncertainty about price movements.

The government could just as easily pay the same return on bank reserves held at the central bank if it wanted to provide a reward to the private sector. The point is that a reserve balance is equivalent to a 1-day government bond with zero return (unless there is a support rate paid). Draining the reserves by issuing a government bond merely alters the duration composition of the outstanding government securities.

Kalecki then showed why the central bank can always maintain “the rate of interest at a certain level … however large the amount of government borrowing.” He said that:

In spite of astronomical budget deficits, the rate of interest has shown no rise since the beginning of 1940.

As is the case in the current period. The central bank sets the interest rate and it can control longer-term interest rates if it so chooses. There is a question as to whether it can control all rates. It can but that would require it to offer an infinite fixed-price offer for all securities, which is not practical. But by controlling key rates (for example, longer term bonds) the central bank can condition the other rates via shifts in portfolio compositions.

Finally, to complete his story on what a Keynesian expansion involves he said:

It may be objected that government expenditure financed by borrowing will cause inflation. To this it may be replied that the effective demand created by the government acts like any other increase in demand. If labour, plants, and foreign raw materials are in ample supply, the increase in demand is met by an increase in production. But if the point of full employment of resources is reached and effective demand continues to increase, prices will rise so as to equilibrate the demand for and the supply of goods and services … It follows that if the government intervention aims at achieving full employment but stops short of increasing effective demand over the full employment mark, there is no need to be afraid of inflation.

Once again, a very similar story to that offered by MMT. In this paragraph it is clear that unless inflation is sourced from a cost shock (like an energy price hike), then expanding nominal aggregate demand will only come up against what Keynesians used to call the “inflation barrier” if there is no capacity of the real economy to respond to that demand impulse.

I have often indicated that my economic roots come from Marx through Kalecki. Kalecki was a Marxist economist. Marx was the first to really get to grips with the idea of effective demand – that is, spending backed by cash. Kalecki understood this intrinsically.

There has been a debate which fascinated me as a graduate student as to whether Keynes was influenced by Kalecki’s work as he wrote the General Theory which was published in 1936. Keynes had published the Treatise on Money in December 1930. At this stage Keynes, influenced by his mentor Alfred Marshall was still operating in the Quantity Theory of Money paradigm. However the Treatise demonstrates that Keynes was starting to have doubts about the mainstream macroeconomics that he was operating within.

For a start he observed changes in monetary aggregates that were not associated with changes in the price level and vice versa. That possibility had to that date been denied by economists working in this tradition. He started to look for alternative explanations for inflation and focused on the relationship between investment and saving. He noted that if investment was greater than saving then inflation will result and vice versa. He realised then that when the economy is recessed (saving draining demand more than investment is injecting demand) then spending had to be stimulated and saving discouraged.

At the time, the then orthodoxy claimed that thrift was needed when there was recession. Keynes said of this “For the engine which drives Enterprise is not Thrift, but Profit.”

So there was some hint that he was moving away from the “classical” tradition and moving along a path that would realise the General Theory some six years later. But it remains that the Treatise was still very much a work within the Quantity Theory of Money tradition.

Kalecki, however, never worked in that tradition. He clearly understood what Marx had been writing in the Theory of Surplus Value about effective demand and in 1933 published (via the Research Institute of Business Cycle and Prices in Poland) a famous piece in Policy Proba teorii koniunktury, which broadly translates to a Search for a Theory of Demand and outlined his very comprehensive understanding of business cycle dynamics. It is a very rich model of the macroeconomy and how aggregate demand interacts with the aggregate supply capacity of the economy.

He presented his theory in 1933 to the International Econometrics Association, which was a prestigious body. He subsequently published the paper in English in 1935 (in Econometrica). So a much richer version of the General Theory was in the public arena some 3 years before Macmillan published Keynes’ tome.

Joan Robinson, who was a Cambridge academic at the time, wrote later in her Collected economics papers that:

Michal Kalecki’s claim to priority of publication is indisputable. With proper scholarly dignity (which, however, is unfortunately rather rare among scholars) he never mentioned this fact. And, indeed, except for the authors concerned, it is not particularly interesting to know who first got into print. The interesting thing is that two thinkers, from completely different political and intellectual starting points, should come to the same conclusion. For us in Cambridge it was a great comfort.

Kalecki did not meet Keynes (at Cambridge) until 1937 and the latter was fairly dismissive. The issue of whether Keynes had been influenced by Kalecki’s earlier work remains unresolved. Staunch followers of Keynes say no, whereas those scholars who do not see Keynes as being the central figure in the development of the theory of effective demand, such as me, lean to the view that the transition from the Treatise (1930) to the General Theory (1936) was so great that it is likely that Keynes knew what Kalecki had written and published and was influenced by it.

The 1943 article that I have been discussing in this blog – The Political Aspects of Full Employment – extended Kalecki’s business cycle model to include political considerations.

Anyway, all that was a digression.

After outlining the economics of effective demand and showing that technically full employment was the logical consequence of a government permitted to use its fiscal capacity to manage total spending, Kalecki then introduced what he called the political aspects.

Accordingly, Kalecki (1971: 138) said:

… the assumption that a Government will maintain full employment in a capitalist economy if it knows how to do it is fallacious. In this connection the misgivings of big business about maintenance of full employment by Government spending are of paramount importance.

The alleged opposition by big business to full employment mystified Kalecki because the higher output and employment would seemingly be of benefit to workers and capital alike.

Kalecki (1971: 139) lists three reasons why the industrial leaders would be opposed to full employment “achieved by Government spending.”

- The first is an assertion that the private sector opposes government employment per se.

- The second is an assertion that the private sector does not like public sector infrastructure development or any subsidy of consumption.

- The third is more general and involves a dislike by the private sector “of the social and political changes resulting from the maintenance of full employment” (emphasis in original).

One is tempted to respond to Kalecki with the reference to the long period of growth and full employment from the end of WWII up until the first oil shock (excluding the Korean War). During that period, most economies experienced strong employment growth, full employment and price stability, and strong private sector investment over that period under the guidance of interventionist government fiscal and monetary policy.

This period of relative stability was only broken by a massive supply shock (OPEC petrol price hike), which then led to ill advised policy changes that provoked the beginning of the malaise we are still facing after 25 years.

In Kalecki’s defence, it might be argued in reply that it took 30 odd years of the Welfare State to generate the inflationary biases that were observed in the 1970s. This is a popular view to explain why it took so long for the Keynesian consensus to break down.

Kalecki (1971: 139-140) explains how the dislike by business leaders of government spending:

… grows even more acute when they come to consider the objects on which the money would be spent: public investment and subsidising mass consumption.

So he is asserting that the private sector is just anti-government if the public activities do not favour their narrow sectoral interests. However, there was never a convincing argument presented then or by the progressives who still use the 1943 argument by Kalecki to justify their own scepticism about full employment policy approaches such as the Job Guarantee.

If public spending overlaps with private spending (the classic example is toothpaste) then according to Kalecki, 1971: 140):

… the profitability of private investment might be impaired and the positive effect of public investment upon employment offset by the negative effect of the decline in private investment.

So business leaders will be very well suited according to Kalecki if there is no such overlap. But ultimately the government will want to move towards nationalisation of industries to broaden the scope for investment. This criticism is inapplicable to a buffer stock route to full employment. Job Guarantee jobs are most needed in areas that have been neglected or harmed by capitalist growth. The chance of overlap and therefore substitution is minimal.

Of-course, I am not arguing that the government might use the Job Guarantee as an industry policy and may deliberately target an overlap to drive inefficient private capital out of the economy. That would be beneficial but would probably engender resistance from private capital of the type Kalecki noted in this article.

Kalecki (1971: 140) acknowledges that the “pressure of the masses” in democratic systems may thwart the capitalists and allow the government to engage in job creation. It is clear that one of the features of the neo-liberal era has been the vehemence in which they have pursued public indoctrination aimed at changing our attitudes to full employment and the jobless. In Australia, a vile nomenclature was developed in the 1980s and refined since then to vilify the unemployed and to imprint in the public mind that unemployment was voluntary and due to laziness, poor attitudes or inability to apply oneself to personal skill development.

The idea that mass unemployment was an outcome of systemic failure at the macroeconomic level was actively eschewed by the plethora of right-wing think tanks that emerged during this modern era to disabuse us of our previously held views about solidarity and collective action. Please read my blog – What causes mass unemployment? – for more discussion on this point.

With that in mind, Kalecki’s principle objection then seemed to be that “the maintenance of full employment would cause social and political changes which would give a new impetus to the opposition of the business leaders.” The issue at stake is the relationship between the threat of dismissal and the level of employment.

In this regard, Kalecki (1971: 140-41) says:

Indeed, under a regime of permanent full employment, ‘the sack’ would cease to play its role as a disciplinary measure. The social position of the boss would be undermined and the self assurance and class consciousness of the working class would grow.

Kalecki is really considering a fully employed private sector that is prone to inflation rather than a mixed private-Job Guarantee economy. The Job Guarantee creates loose full employment rather than tight full employment because the buffer stock wage is fixed (growing with national productivity). The government never competes against the market for resources in demand when it offers an unconditional job to any unemployed workers under a Job Guarantee. By definition, any worker who takes a Job Guarantee job has zero bid in the private market (that is, no private firm is prepared to pay for their labour at the prevailing wages and prices).

The issue comes down to whether the Job Guarantee pool is a greater or lesser threat to those in employment than the unemployed when wage bargaining is underway. This is particularly relevant when we consider the significance of the long-term unemployed in total unemployment. It can be argued that the long-term unemployed exert very little downward pressure on wages growth because they are not a credible substitute.

The Job Guarantee workers, however, do comprise a credible threat to the current private sector employees for several reasons:

- The buffer stock employees are more attractive than when they were unemployed, not the least because they will have basic work skills, like punctuality, intact.

- This reduces the hiring costs for firms in tight labour markets who previously would have lowered hiring standards and provided on-the-job training. Firms can thus pay higher wages to attract workers or accept the lower costs that would ease the wage-price pressures.

- The Job Guarantee policy thus reduces the “hysteretic inertia” embodied in the long-term unemployed and allows for a smoother private sector expansion because growth bottlenecks are reduced.

The Job Guarantee pool provides business with a fixed-price stock of skilled labour to recruit from. In an inflationary episode, business is more likely to resist wage demands from its existing workforce because it can achieve cost control. In this way, longer term planning with cost control is achievable.

So in this sense, the inflation restraint exerted via the fluctuating employment buffer stock under the Job Guarantee is likely to be more effective than using a fluctuating unemployment buffer stock under the mainstream NAIRU strategy.

The International Labour Organisation (1996/97) says, “prolonged mass unemployment transforms a proportion of the unemployed into a permanently excluded class.” As these people lose their skills, warns the ILO, they are no longer considered as candidates for employment and “cease to exert any pressure on wage negotiations and real wages.” The result is that “the competitive functioning of the labour market is eroded and the influence of unemployment on real wages is reduced.”

In what form does Kalecki see the opposition by capitalists coming? I am leaving aside the political rationale where presumably funds directed to sympathetic political parties and control of the media could all be effective means to oppose an incumbent government. He is very vague about what might transpire.

Kalecki (1971: 142-143) outlines that counter-stabilisation policy is not a concern of business as long as the “businessman remains the medium through which the intervention is conducted.” Such intervention should aim to stimulate private investment and should not “involve the Government either in … (public) investment or … subsiding consumption.”

Kalecki (1971: 144) says if attempts are made to

… maintain the high level of employment reached in the subsequent boom a strong opposition of ‘business leaders’ is likely to be encountered. As has already been argued, lasting full employment is not at all to their liking. The workers would ‘get out of hand’ and the ‘captains of industry’ would be anxious to teach them a lesson.

But how would they do this? Kalecki seems to imply that the reaction would work via business and rentier interests pressuring the government to cut its budget deficit. Presumably, corporate investors could threaten to withdraw investment. An examination of the investment to income ratio in Australia over the period since the 1960s is instructive.

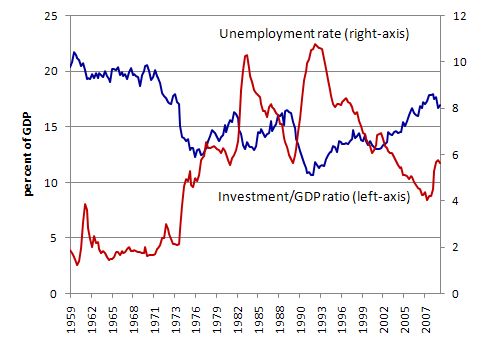

The following graph shows shows the investment ratio and the unemployment rate for Australia from 1959 to 2009 using labour force and national accounts data available from the Australian Bureau of Statistics).

The investment ratio moves as a mirror image to the unemployment rate, which reinforces the demand deficiency explanation for the swings in unemployment. The rapid rise in the unemployment rate in the early 1970s followed a significant decline in the investment ratio. The mirrored relationship between the two resumed albeit the unemployment rate never returned to its 1960s levels.

Far from being a reason to avoid active government intervention, the Job Guarantee is needed to insulate the economy from these investment swings, whether they are motivated by political factors or technical profit-oriented factors.

Another factor bearing on the way we might view Kalecki’s analysis is the move to increasingly deregulated and globalised systems. Many countries have dismantled their welfare states and enacted harsh labour legislation aimed at controlling trade union bargaining power.

Trade union membership has declined substantially in many countries as the traditional manufacturing sector has declined and the service sector has grown. Trade unions have traditionally found it hard to organise or cover the service sector due to its heavy reliance on casual work and gender bias towards women.

It is now much harder for trade unions to impose costs on the employer. Far from being a threat to employers, the Job Guarantee policy becomes essential for restoring some security in the system for workers.

There have been major reductions in barriers to international trade and global investment over the last 20 years. While globalisation may still not have as large an impact on depressing wages as say the effects of declining union membership, anti-labour legislation and corporate restructuring, there is still concern about the destruction of jobs in manufacturing and the downward pressure on wages.

Richard Du Boff wrote in his 1997 article – Globalization and Wages, The Down Escalator – published in Dollars and Sense:

As international trade wipes out jobs in manufacturing, the displaced workers seek jobs somewhere in the service sector, exerting downward pressure on the wages of maintenance and custodial workers, taxi drivers, fast food cooks, and others who hold similar positions. Even if the displaced workers can be absorbed easily, their new service jobs will usually pay less than their old jobs, pulling down average low-skill wages. And the effects will not be restricted to low-skilled labor. A worldwide labor supply network is now extending to middle-range skills. India has a large pool of English-speaking engineers and technicians who make roughly the same wages as low-skilled workers in the United States.

Finally, but looking to the future, those who criticise the Job Guarantee from a Kaleckian viewpoint have to address the issue of binding constraints. Kalecki comes from a traditional Marxian framework where industrial capital and labour face each other in conflict. The goals of capital are antithetical to those of labour.

In this environment, the relative bargaining power of the two sides determines the distribution of income and the rate of accumulation. Industrial capital protects its powerful position by balancing the high profits that come from strong growth with the need to keep labour weak through unemployment.

However, the swings in bargaining power that have marked this conflict over many years have no natural limits. But the concept of natural capital, ignored by Kalecki and other Marxians, is now becoming the binding constraint on the functionality and longevity of the system.

It doesn’t really matter what the state of distributional conflict is if the biosystem fails to support the continued levels of production. The research agenda for Marxians has to embrace this additional factor – natural capital.

The concept of natural capitalism developed by Paul Hawken and others provides a path for full employment and environmental sustainability within a capitalist system.

So who are the deficit terrorists?

My argument here does not seek to disabuse anyone of the notion that there is no political lobby that is well organised and against the fiscal intervention by government – that is, when the benefits do not flow to some narrow wealthy sectoral interest group (like Wall Street bankers).

Quite clearly we are witnessing an obscene campaign that is successfully opposing the use of fiscal stimulus and undermining the well-being of a great many people. But it is also undermining the core industrial sectors like manufacturing and construction where the old “captains of industry” were prominent.

This blog is now having to conclude (my train journey is nearly over and it is too long anyway). So I will address this issue again another day. One of my PhD students (our guest blogger Victor) is nearly ready to submit his thesis and he will write more for us on the political constraints to full employment.

The point I would make is that the major political blockages are no longer those that Kalecki foresaw. The opponents of fiscal activism are a different elite and work against the “captains of industry” just as much as they work against the broader working class.

The growth of the financial sector and global derivatives trading and the substantial deregulation of labour markets and retrenchment of welfare states has altered things considerably since Kalecki wrote his brilliant article in 1943.

Saturday Quiz

Back tomorrow. If you are sick of it have a day or two off. If not have a go and see how much progress you are making (notwithstanding the dilemmas that emerge when my questions suck!)

And so ends my train blogging – and that is enough for today!

“The chance of overlap and therefore substitution is minimal.”

That I disagree with. Outsourcing is a perfect example of where the private sector gets involved in public services. And there are plenty of examples I can think of where the public sector elephant tramples inadvertently on private sector small businesses – the provision of training and business services for example, or particularly elderly care. I’ve seen people bankrupted by public subsidy, or ‘competitive nationalisation’ as it is probably better described as.

For me the overlap must be dealt with as a matter of design, and not require the Solomon like decision of some public official. The simplest way to do that is to effectively nationalise the minimum wage and subsidise all ‘work’ (including normal jobs, JG jobs, volunteer positions and ‘domestic caring’ – young or elderly). Then balance with taxation if required. The debate then is whether the balancing taxation should be on profit, assets or transactions.

This then makes the overlap argument redundant.

Bill ~

Sorry to toss another article at you so soon, but a Bloomberg article by BU econ Prof Laurence Kotlikoff, “U.S. Is Bankrupt and We Don’t Even Know It”, is getting major attention here (blogs, talk radio, etc.) in the US, and is scaring the crap out of people with nonsense (and HUGE numbers) dressed up in a PhD. I frankly think Bloomberg was a little irresponsible featuring an article with such outlandish claims that was clearly designed more to shock than to inform, but I do think that because of this, an appeal might reasonably be made to Bloomberg to equally highlight an article disputing Kotlikoff’s claims (which of course would have to be authored by someone of credentials similar to Kotlikoff’s). Maybe you heavyweights might flip a coin for the honors? People really need to be disabused of Larry’s ideas, and Larry needs to be put out of his misery before he does anymore damage. (His students might also consider asking for a refund.) Thanks.

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2010-08-11/u-s-is-bankrupt-and-we-don-t-even-know-commentary-by-laurence-kotlikoff.html

Dear Benedict@Large

It is on my list for next week. I have several articles to clarify that are similarly misguided. I had a big reading day on the train today!

best wishes

bill

“One is tempted to respond to Kalecki with the reference to the long period of growth and full employment from the end of WWII up until the first oil shock (excluding the Korean War). During that period, most economies experienced strong employment growth, full employment and price stability, and strong private sector investment over that period under the guidance of interventionist government fiscal and monetary policy.”

The so called ‘Golden Age’.

I don’t know if you have seen this?

There is an interesting book on UK postwar economic policy at

http://www.press3.co.uk/publications/to_full_employment/chapters/

Incomplete sentence or paragraph:

“Remember he was writing in 1942 and while governments had gone off the gold standard there was still the…”

I also spotted that Kotlikoff article yesterday and wasn’t impressed.

I agree with Bill that Kalecki’s objections to full employment (at least as set out by Bill) are weak. But I disagree with several of Bill’s other points, as follows.

Bill says “Any private operators who cannot “afford” to pay the minimum should exit the economy.” Why then is it justified to set up public sector “job guarantee” jobs which cannot afford to pay the minimum (without the help of what is in effect a subsidy)? Put another way, if we are going to have temporary subsided public sector jobs (i.e. JG), why not also have temporary subsidised private sector jobs, particularly as the private sector is much better at employing unskilled labour than the public sector?

Bill also says “This would see labour being transferred from the inflating sector to the “fixed wage” sector…”. My answer: it is totally misleading to describe the private sector as “inflating” and the public sector as “not inflating”. Reason is thus. If JG schemes are to be reasonably efficient, they have to employ permanent skilled labour, capital equipment, materials, etc, i.e. factors of production other than temporary JG employees. And these factors of production cannot just be withdrawn from the existing economy or ordered up from the existing economy, because the latter, as Bill concedes, is at the level of employment at which inflation is a threat. In short, I suggest that setting up a public sector operation that employs a given set of factors of production has exactly the same inflationary effect as setting up a private sector operation employing the same set. I go into this point in more detail here: http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/19094/

Kotlikoff has been described as the “guru of the Governor of the Bank of England”. See:

http://business.timesonline.co.uk/tol/business/industry_sectors/banking_and_finance/article7005471.ece

On the strength of that I’m reading Kotlikoff’s book on limited purpose banking, “Jimmy Stewart is Dead”. But I think his ideas involve too much bureaucracy. Can we have Bill’s thoughts on this?

I really enjoyed the digression on Marx, Kalecki and Keynes. It’s Friday night, I’m listening to the footy, reading about all my favourite economists. Very pleasant. More digressions in the future, please. 🙂

You write: “Marx was the first to really get to grips with the idea of effective demand.” You are wrong. Malthus beat him to it, as did Sismondi, both writing about effective demand in the 1820s. But it was the Earl of Lauderdale who, having broken with, as he said, ‘the superstitious worship of Adam Smith’s name’, warned Parliament in 1804 that when the Napoleonic War was finally over, care should be taken to ensure an ‘abstraction of demand’ did not precipitate a collapse of prices of such proportion ‘as to discourage reproduction’. He added prophetically: ‘they must be cautious not to mistake, for the effects of abundance, that which in reality may be the effect of failure of demand.’ The economic depression which followed Waterloo lasted a full decade and nearly precipitated a bloody revlution..

Dear Bill,

After reading your article I started digging deeper about Michal Kalecki. My mom was right (she remembered the events of 1968 very well) and I was completely wrong in thinking that Kalecki had had anything to do with the sins of the communist regime in Poland.

Kalecki was never a Stalinist communist but belonged to the progressive socialist tradition. He never compromised his personal integrity and was persecuted in 1968. He actually anticipated the serious economic problems facing Poland in the late 1960-ties which led to the riots and shooting of shipyard workers in 1970.

It is sad to read that the memory of Michal Kalecki has been erased in Poland after 1989 again. Only a few of people who belong to his school of thought are still active however they have been marginalised as everyone who is not a neoliberal or Catholic nationalist.

Sometimes it takes years to get un-brainwashed. I am so happy that I left that dysfunctional society and my kids do not have to grow up listening to hate speech against anyone who dares to think differently.

That’s why I don’t want to see the same social processes occurring here in Australia…

REFERENCE_IN_POLISH_http://www.sgh.waw.pl/ogolnouczelniane/100lat/Sylwetki/kalecki

Hi Bill,

you are constantly highlighting (and I totally agree with you) the importance of the biosystems carrying capacity and the availability of real resources as the key question for the future.

In this respect I’d like to ask you (and everybody who is posting here) how familiar you are with the work of Lester Brown (Plan B 3.0 available here: http://www.earth-policy.org/images/uploads/book_files/pb3book.pdf – I haven’t read it so far) and/or Herman Daly (Beyond Growth) and what you think about it; and if there are any other people that have done any reasonable work on environmental sustainability.

Have a good weekend

Tomme

As a Polish guy let me just mention that Kalecki’s article “Proba teorii koniunktury” best translates as “Attempt at Business Cycle Theory”.

I agree with Adam above, most economists in Poland are of neoliberal persuasion. Poland was very opened for a communist country, people were allowed to go to US on various stipends to study economics, most of them ended up embracing the market-uber-alles ideology. Kalecki’s works were published again after 1989, but he is treated as a historic curiosity.

Another aside: if you want to pronounce “Kalecki” correctly, say “Kaletski”; a word pronounced “kalecky” in Polish means “crippled”, “lame”, “disabled” and Kalecki is not that 🙂

Regarding Kotlikoff, my paper, “interest rates and fiscal sustainability” at cfeps rebuts in detail his fiscal gap measure, for those interested.

I believe that the political constraints are fundamental and make it difficult to imagine very pragmatic programs (such as the JG) being implemented in the current environment. These political constraints are based on economics, but are not material in nature. This economic factor is time – and the political objective is to limit the time available for change activities. This is the point of labour time – and why exchange value can only be extracted from living labour.

Any program that has a possibility of providing additional time (more free time) to those with interests opposed to those in power will be thwarted. In the US we have seen this in health care, education, transportation, public pensions, industrial policy, and now with the net neutrality controversy, to reduce the time-providing benefits of the internet.

I have not read Kalecki to understand the basis his criticisms – but it seems that the way ‘captains of industry’ (more accurately, the political leadership of those with power) are doing this is to actively cripple the efficiency of an incredibly powerful global economy. We are seeing more and more irrational economic distortions being implemented consciously (well, perhaps blinded slightly by ideology) by policy leaders. This is not because more rational policies would damage the private economy, but that just the possibility of losing political control is too great of a risk to consider even trying to allow decent policies to gain a foothold in the public mind.

The fight for a JG should never be abandoned – in some ways it is a fight to educate those that would benefit – if it cannot be practically implemented given current political conditions, I hope this reveals to the public that our politics need to be fundamentally altered.

Bill,

I sent Kalecki’s article to Mark Thoma a few weeks back. It got some attention. I’m glad to see you re-read it.

Kalecki didn’t care much about capitalism, and his arguments in favor of eliminating unemployment follow from his preferences and values. If, however, one prefers capitalism to market socialism than one must accept some form of unemployment as a necessary buffer. Corporations simply cannot pay workers a LOW enough wage to justify the complete reduction of unemployment in a modern capitalist state. Just as Disneyland could not abolish lines at its popular rides without Raising the price of each ride. See Romer’s 1987 article on Ski-Lift Pricing. Auctioning rides and ending unemployment are great in theory yet are incompatible with market based economies. If you are indifferent between capitalism and market socialism (or prefer socialism) than, well, more power to ya mate.

This is not just a statement of belief. Abba Lerner admitted as much in his 1943 piece on Functional Finance. He just didn’t care too much about capitalism. And Oscar Lange, the forefather of market socialism, ended up running State Planning Boards in Poland. That didn’t exactly work too well last time around. Kalecki was as hostile as any to Big Business.

If, on the other hand, you believes that economic dynamism, technological innovation, and creative destruction are important and desired social goods, then one must allow for some buffer of unemployment. A market system brings new technolgical goods and services about. Socialism (with a small “s” or large) has not exactly succeeded in this respect.

MMT adherents who value capitalism are in a bind. You can’t have no unemployment without a weakened role for the private sector in periods of secular stagnation (like Japan). Kalecki liked this….How about you?

respectfully,

Nick R.

Kyoto

“The Political Aspects of Full Employment”

What about the political aspects of full retirement?

If 3 billion people can produce enough for 6 billion people but 4 billion need jobs, what should happen?

“U.S. Is Bankrupt and We Don’t Even Know It”

Let’s bring this to the present in the USA. If loan losses are 2 trillion to 4 trillion and there is only a little less than 1 trillion in currency, does that define bankruptcy?

“So who are the deficit terrorists?”

I am one of the people against the debt deficit. Both gov’t debt and private debt have at least one similar property. That is both can cause differences between spending and earning that can cause “budget” (whether gov’t or private) problems in the future.

Nick R said: “If, however, one prefers capitalism to market socialism than one must accept some form of unemployment as a necessary buffer.”

A necessary buffer against what? Wage inflation?

And, “Corporations simply cannot pay workers a LOW enough wage to justify the complete reduction of unemployment in a modern capitalist state.”

What about reducing the number of workers?

And, “If, on the other hand, you believes that economic dynamism, technological innovation, and creative destruction are important and desired social goods, then one must allow for some buffer of unemployment. A market system brings new technolgical goods and services about.”

Let the new technological goods and services compete over few workers. This should keep wages high enough that the chances of the new goods and services becoming asset bubbles is reduced. It seems to me that the internet bubble and housing bubble are good examples.

bill said: “The Job Guarantee would be funded by the sovereign government which faces no financial constraints in its own currency. In the context of the current outlays that are being thrown around in national economies, the investment that would be required to introduce a full blown would be rather trivial. It would be operated locally though.”

Can you make that simpler? Do you mean currency or debt? If you say credit an account somewhere, are you going to guarantee 1 to 1 convertibility into currency?

bill said: “The point is that a reserve balance is equivalent to a 1-day government bond with zero return (unless there is a support rate paid).”

Yes! This needs to be pointed out over and over again until even kudlow understands it.

The other thing to note is that I don’t believe central bank reserves can directly leave the banking system.

It is as simple as this. If the fed is “printing” excess central bank reserves, it is trying to price inflate with debt. However, the fed and almost all economists can’t understand that the solution to too much debt is NOT more debt whether gov’t or private.

Nick R.

1. Stalinist communism was introduced to Poland by the Soviet Army and NKVD in 1944 It did not evolve from the system proposed by Oskar Lange. The statement you made that “Oscar Lange, the forefather of market socialism, ended up running State Planning Boards in Poland. ” doesn’t prove that there are any risks of introducing a totalitarian system when we violate the axioms of the current neoliberal system.

2. In Australia a single unemployed person receives $462.80 fortnightly and has to spend their time looking for often non-existing job or attending often useless programs. So if these people are paid $500 fortnightly (I’d obviously pay them more) and for example work on removal of invasive species (virtually nobody does it now so they keep overgrowing native vegetation) the capitalist model will be replaced by market socialism. Could you please explain referring to the example provided above how this will happen?

3. So you reckon that “a weakened role for the private sector in the periods of secular stagnation” is worse than the following British / Polish implementation of the “buffer”:

REFERENCE_http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2010/aug/12/homeless-poles-rough-sleepers

Even if you are right (I am not convinced) about the alternative (or rather “TINA”) presented in the comment, I disagree with the choice you would make.

N.B. The Guardian’s article itself may not be correct.

“Many EU rough sleepers stay in London because they think – often incorrectly – there is a only a limited safety net in their own country.”

I am afraid these people who move back to Poland will simply be homeless again there because there is a very limited safety net in Poland. About 300 homeless died this winter despite a dramatic improvement in the GDP and wealth of some social groups over the last decade.

Do you want to hear more stories about the Great Neoliberal Experiment from Central Europe? Should I find some photos?

I believe that we remove the TINA argument, neoliberalism is intellectually dead.

1. I am glad to see the work of Kalecki being discussed in Billyblog, a thinker hidden in the shadow of Keynes but of equal importance to me as an economist. I am indebted to my former teacher and great economist Tom Asimakopulos who introduced Kalecki to me and to many other PostKeynesian economists. He was one of the first that analyzed Kalecki’s work and the importance of the profit reduced form( multiplier) equation which is more relevant for a capitalist economy than the income multiplier equation as well as his work with the business cycle.

2. Reagarding the Job Guarantee Proposal I should point out what I have said in previous comments on the topic. Public employment programs should be mainly a permanent job creation project that can reduce private employment instability and only as a last resort be used as a control instrument of buffer stocks. The idea is to promote jobs not for market services based on shelfish interest with competition that react with a work/reward feedback which is unstable as proprietary profit interests change, but jobs for community sevices based on social responsibilty with solidarity that react with a donation/grace feedback which produces stabilty, limiting buffer stocks application that have turnover costs. Full employment and economic stability is enhanced by sustaining a larger public sector offering employment that services social purpose with less net waste if we consider the hidden costs of (un/under)empoyment and the externalities upon the environment and society that the private sector imposes.

Adam (AK), to your 4 points…..

1.) It’s telling that Lange choose to run state planning boards. He didn’t invent Stalinism, he just signed up for it.

2.) The more business executives anticipate higher taxes or inflation at some future point, the less they are willing to spend on corporate capex today. The less businesses spend on new investments today the more the government has to fill in the gap. Ad infinitum.

3.) Thank you for recognizing that we are in fact making a choice. You can’t have free markets and MMT-like socialism.

4) That is the price to be paid for a capitalistic economy. Think about Poland circa 1950 when both Kalecki and Lange were running a parts of Communist Poland’s repressive and vile gov’t……would you prefer that? I think you can pay some insurance or welfare to citizens without giving them guaranteed jobs, and still preserve capitalism. Schumpeter said the same thing about the value of the dole in 1934. Doing more exacts a cost…..if you care about the value of private markets. Kalecki and Lange didn’t care — actually they hated capitalism.

—-

And “Fed Up” the buffer is to preserve a private market-based economy, not a market socialist — or worse — one.

Nick R.

Kyoto

Nick R,

1. Kalecki was working in New York for the UN in 1950 so blaming him for Stalinism is absolutely incorrect.

REFERENCE_http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Micha%C5%82_Kalecki

2.”The more business executives anticipate higher taxes or inflation at some future point, the less they are willing to spend on corporate capex today. The less businesses spend on new investments today the more the government has to fill in the gap. Ad infinitum.”

I believe Bill has already addressed this issue:

“In general, it is the outlook for profitability, rather than the price of credit, that influences investment.”

REFERENCE_https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=5402

3. To me reducing human life to the free market value has nothing to do with any moral values. Humans are not a fertiliser for the free market economy.

4. Comparing MMT or any kind of state intervention in the economy to Stalinism is a straw-man “TINA”-like argument. Can you prove that any state intervention / MMT is (or leads to) “Real Socialism” what is (or leads to) Stalinism?

Please be aware that I lived in a communist country (in the “Real Socialism” period) so I may know the difference.

Adam (ak),

1. I maintain that Kalecki was a Polish marxist economist who chose to move back to Poland in post-war ’40s in order to help the Revolution. I don’t “blame him for Stalinism”, I blame Iosif Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili for Stalinism.

3.Capitalism as human fertliser? I suppose your choice of human soil improver has its merits.

4. I don’t say that MMT leads inexorably to Stalinist Communism. I maintain that MMT’s governing philosophy is indifferent between marekt socialism and modern capitalism. And I believe that most MMT adherents are indifferent between market socialism and modern capitalism. Market socialism could very well lead to Communism, but that is my issue with it. It is problematic on its own merits.

Nick R.

Nick R says “Corporations simply cannot pay workers a LOW enough wage to justify the complete reduction of unemployment in a modern capitalist state.” I suggest there is no need to cut the wages of 90% of employees because 90% of employees are economically viable at their current wages.

It’s those who temporarily cannot find suitable work (i.e. the unemployed) who would find work if they were available to employers at say $1 an hour. So devise a system that distinguishes these people from the above 90%, 2, subsidise the “temporarily unsuitable”, and 3, hey presto, you have the advantages of capitalism plus full employment (or something nearer it than currently obtains).

The latter is what JG is, more or less. My main quarrel with JG is that JG (Bill Mitchell style) is confined to the public sector, whereas I think it can be extended to the private sector.

Also I don’t see any INHERENT characteristic of socialist economies that guarantees full employment. The old USSR undoubtedly had significant numbers of people who couldn’t find work: the USSR just denied that these people existed. Plus a wheeze they employed to minimise overt unemployment was restrictions placed on employers wanting to sack staff. In effect, individual employers subsidised their own “temporarily unsuitable” employees. The latter system is fairly similar to JG, the difference being that under JG the state does the subsidising, whereas in the USSR, individual employers did the subsidising.

Nick

“MMT adherents who value capitalism are in a bind. You can’t have no unemployment without a weakened role for the private sector in periods of secular stagnation (like Japan). Kalecki liked this….How about you?”

As far as I recall Bill doesn’t talk about no unemployment, he talks about full employment – which is defined as less that 2% unemployment, no underemployment or hidden underemployment. In other words all those that want a job can have one.

Ralph

“It’s those who temporarily cannot find suitable work (i.e. the unemployed) who would find work if they were available to employers at say $1 an hour. So devise a system that distinguishes these people from the above 90%, 2, subsidise the “temporarily unsuitable”, and 3, hey presto, you have the advantages of capitalism plus full employment (or something nearer it than currently obtains).”

More simply would be to nationalise the minimum wage, pay it to everbody engaged in ‘useful work’ and scrap other benefits. You then get the same advantage but with a lot less bureaucracy. All you have to do is identify if they are in ‘useful work’ or not. I believe you do that with things called timesheets 🙂

Then the JG buffer jobs are just the same as charity volunteer positions or ‘domestic caring’ and it all just works. No overlap, no socialism, just using the market to deliver outcomes.

PUBLIC VS PRIVATE ENGAGEMENT

Our capacity to engage has an orientation depending on the conditions of the regime (environment, society) set and its terms of a) symbiosis that determine common attributes/rights of a public domain and b) its terms of osmosis that determine proprietary attributes/rights of a privaet domain. The public domain is operated as civilization and behaved/adjusted as community while the private domain is operated as capital and behaved/adjusted as market.

The means of capital operation is production that converts nature into capital and humanity into labor. On the other hand, the means of civic operation is culture that cultivates nature into civilization and humanity into demos. Productive conversion is destroying natural resources into artificial materials and labor into productive skills in order to be reconstructed/reestimated or operated as material/human capital. On the other hand, cultivation is to encourage natural and human resources to flourish and enrich/advance with added quality yield in beauty and knowledge respectively in order to be renovated and glorified or operated aesthetically as civilization of art and science.

Orientation matters and its composition seperates reality from barbarism to hellenism, operational criteria of utility/physics from aesthetics and behavioral criteria of reason from ethics. The proper optimization is not extremum but the metric of sustenance which is ariston as it balances opposites, harmonizes criteria and internalizes collateral effects.

Ralph,

Point well taken. Why not simply halve the minimum wage? More unemployed workers will find jobs and the system will stay capitalist and dynamic.

I also agree with you that there in nothing inherent about soviet style socialism and full employment.

My main point is that if the state is allowed to run up endless debts then the private sector (rightly or wrongly) will incorporate the cost of paying down these debts in determining their expected long-run return on new capital expenditures. Under secular stagnation conditions (like Japan today, and maybe the rest of the developed world) this will cause the private sector to continually shrink relative to the public sector. Market socialism — or worse — will replace capitalism. And the cost is that the economy will become less dynamic, more rigid, and less innovative. See Japan circa 1990-2010.

And Neil, I didn’t realize that Bill believed in 2% NAIRU. Thanks for that. Some MMTers strangely think NAIRU is zero!

Nick R.

Kyoto

Bill: I would abandon the unemployment benefits scheme and free the associated administrative infrastructure for Job Guarantee operations.

In the US there are two separate programs, unemployment insurance that workers pay into and welfare (the dole) of people that don’t qualify for the former. The purpose of unemployment insurance is to prevent underemployment by giving those out of work a reasonable opportunity to find comparable employment. People on UI are quick to point out that they are not taking a handout; they paid for this insurance over the years and are entitled to it now.

One of the big problems that the US has been facing is the loss of “good jobs” that don’t come back and the substitution of “good jobs” with lower wage and lower skill jobs, as well as temporary work that lacks benefits. This is not only an economic problem, it is also becoming a political one as well.

A lot of middle class people who are out of work or find their jobs threatened would not be amenable to a minimum wage JG as a solution that meets their needs. These people have debts to service, maintenance bills to pay, educational expenses for their children, and retirement to plan for. Neither drastic cuts in pay nor underemployment work for them, and they will hold the party in power responsible for their situation. People get it that in a modern society, jobs are necessary, so it is the government’s responsibility to make sure that this is happening at a level that allows people to function in their accustomed social class instead of being crammed down to the bottom.

I don’t see the JG addressing this as you present it above, and it seems that a broader policy would also be required to meet present economic and political needs. Beowulf has an interesting automatic stabilization proposal regarding flexible taxation here. Another post at HuffPo here addresses this problem, observing that it stretches back to Reagan and Thatcher. This retired Silicon Valley exec holds that a comprehensive economic policy managed by the government is required instead of the current neoliberal approach that puts the free market in charge, which patently has not worked. He doesn’t offer any suggestions as to what a comprehensive economic policy would look like, however. So far, this is the question yet to be answered, not only for the US but also for the emerging global economy. One thing is sure, though. It has to be demand-based not asset-based, as is present policy.

Dear Takis,

I am in agreement with both of your comments above. The problem with mainstream economics is that it has no conception of polis (state with its institutions, rulers and “city people,” and demoi (“the small people” of the “country”) uniting in politeia, that is, what know today as constitutional democracy in which citizenship implies “civics.” These issues have been discussed in detail since ancient times, and they were already rather mature when Plato and Aristotle approached them in the 4th century BCE. But we are still grappling with them less than successfully.

The founders of modern political theory read Greek and Latin, and they were well acquainted with this debate. This US Constitution was composed on these ideas, which were prevalent among the educated of the 18th century. This is the basis of the ideal of the French Revolution, liberté, egalité, et fraternité, sums up this thinking about personal freedom as freedom from tyranny, equality as equal rights of persons before the law, and fraternity as what Europeans now call “solidarity,” that is, the mutual relationship of citizens in a community.

On the other hand, classical liberalism developed chiefly in England as a political theory that emphasized freedom of individuals from government constraint and social oppression by the landed upper class, as well as free market principles as a means to achieve maximum utility socially in the most efficient and effective way. Those familiar with ancient thought easily identify the philosophical under;inning of these ideas in anarchy (the antithesis of politeia) and hedonism (the antithesis of reason-based ethics). These “solutions” were criticized in ancient times and thereafter as focusing on individuality at the expense of relationship, when society is comprised of the relationship of individuals. As a result of the inadequate attention paid to relationship, solidarity was marginalized. Moreover, modern liberalism took market capitalism, operating under the supposed guidance of an “invisible hand,” as politically determinative. That view, built on flawed assumptions, led to disaster after disaster, including panics and wars.

Classical liberalism matured into neoliberalism, which attempts to preserve the philosophical foundations of liberalism by gussying them up in complex mathematics (but which is not complex enough to handle complexity). As result, we are still going from disaster to disaster, even though beguiled for awhile by “the Great Moderation.” The chief difference now is that the results are global.

If mainstream economists paid attention to longstanding debate of issues and research in other fields into relevant factors, they might realize that their assumptions are flawed and their models don’t fit reality, which should be obvious to anyone who considers the results of policy directed by this poverty of ideas, which is an affront to the very notion of polity and civics. For example, economics as a science of human behavior is chiefly concerned with choice. The idea of choice that mainstream economics uses is just made up, and it is contradicted by research on other social sciences, as well as cognitive science.

What we have instead is hedonistic anarchy. Plato thought that arising out this would be a new cycle in which the rule of the best qualified (aristoi) would replace the failed system that had been ruled by the venal who had aggregated power in their hands. Aristotle was less sanguine. He saw the inevitable failure as leading to the end of a civilization. History seems to be on the side of Aristotle.

Sorry. But I think this JG is on the long run a bad idea. I tried to accomodate to it but it doesn’t fit. Capitalism and technology work in the opposite direction. People will work less and have more and more leisure. And many people will have only leisure. So what? Beside the bible I know of no law which condemns people to work? The purpose of an economy is not to provide me with employment but the goods and services for a decent life. If these are provided mostly by machines and robots who cares?

Re: The purpose of an economy is not to provide me with employment but the goods and services for a decent life.

Maybe so, but we live in an industrial world, in which we trade comfort and progress for our soul, so it’s necessary to keep the ant heap humming! Industry (machines) + compound interest = our situation (benign -slavery).

The purpose of an economy is not to provide me with employment but the goods and services for a decent life. If these are provided mostly by machines and robots who cares?

Agreed. The history of human development has been a story of the increase in leisure and its extension to more and more people. Thorstein Veblen investigated the leisure as a social and economic phenomenon in The Theory of the Leisure Class, while Joseph Pieper wrote on leisure as the basis of culture in a book of that title.

Leisure is often misunderstood as unproductive. That is not the case at all. People of leisure tend to be highly creative, and their contributions have driven the development of civilization.

Contemporary society needs to rethink the work ethic. It’s becoming passé and is getting in the way of further progress. Of course, this would mean rethinking the basis of present-day capitalism and the type of society based on it.

Thanks, Tom. Humans have certainly advanced in technology and in a few other aspects, but as for “culture,” the great treasures all stem from the traditional past and not the profane present. That aside, I value this blog for the intellectual integrity and decency of its contributors, beginning with Bill Mitchell. Given our context de facto, I believe this economic orientation can give us a measure of equilibrium and justice–and preserve inner freedom, which is the essential

Bill: “My argument here does not seek to disabuse anyone of the notion that there is no political lobby that is well organised and against the fiscal intervention by government – that is, when the benefits do not flow to some narrow wealthy sectoral interest group (like Wall Street bankers). Quite clearly we are witnessing an obscene campaign that is successfully opposing the use of fiscal stimulus and undermining the well-being of a great many people. But it is also undermining the core industrial sectors like manufacturing and construction where the old ‘captains of industry’ were prominent.”

In the US there is presently an unwholesome dynamic where, on one hand, the GOP is traditionally committed to “hard core” neoliberalism and the defense of industrial capitalism against labor incursions. Moreover, “freshwater” academic and professional economists tend to be neoliberal, too. On the other hand, the Democratic Party, supposedly the party of ordinary working people, especially the middle class, is also faced with the need to raise funds for expensive political campaigns and this means going to the people that have the money, typically Wall Street. Of course, there is quid pro quo. As a result, it has diminished the influence of even New Keynesians in recent Democratic administrations. No sign of change in sight, either. If anything, things are getting worse in this regard, as the rise of economic Austrians and political libertarians are pushing the Overton window to the right as they gain influence in the GOP.