I don't have much time today as I am travelling a lot in the next…

Some myths about modern monetary theory and its developers

Today’s economics blog is about some reactions I have to the many pieces of correspondence I get each week about my work via E-mails, letters, telephone calls. It seems that there is a lot of misinformation out there and a reluctance by many to engage in ideas that they find contrary to their current understandings (or more likely prejudices). It always puzzles me how vehement some people get about an idea. A different idea seems to be the most threatening thing … forget about rising unemployment and poverty – just kill the idea!. So here are a few thoughts on that sort of theme.

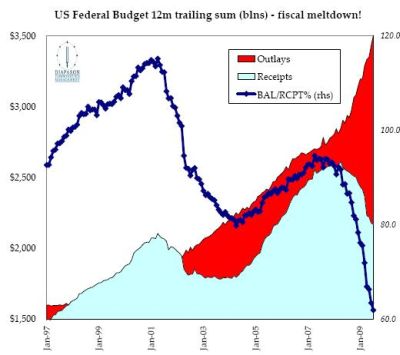

To set the scene consider this graph which was published by the Financial Times in June which is meant to show why US voters should be scared of what the US Government is doing with respect to its budget. It was sent to me by someone who says I should learn from it and “wake up to myself and stop advocating socialism … that he didn’t want to work in one of my crummy public sector jobs”. Okay, I hope he has a job elsewhere.

You will note that the time period begins in 1997 which I think is good (although the article fails to appreciate the significance of that). In fact, the short sample is deliberately intended to deceive and bias the conclusion. As you can see it shows a big splash of red (outlays) currently and a corresponding rapid decline in receipts. Horror story really! Don’t you agree?

Anyone who isn’t quaking in their boots upon seeing this graph is evidently a “delusional or was it fanciful left wing nutter” who “wants to impose socialism on everyone” by forcing “everyone to work for the government”. More about which later.

The first thing to note from the graph is the Clinton surpluses in fiscal years 1998, 1999 and 2000 (increasing each year). And you can guess what happened? The private sector became more heavily indebted than before as the fiscal drag squeezed liquidity. Further, it set up the conditions for a major recession in 2001-02 with unemployment rising sharply and the automatic stabilisers pushing the budget back into deficit. So the stupid graph serves to illustrate some of that which was not mentioned at all in the article.

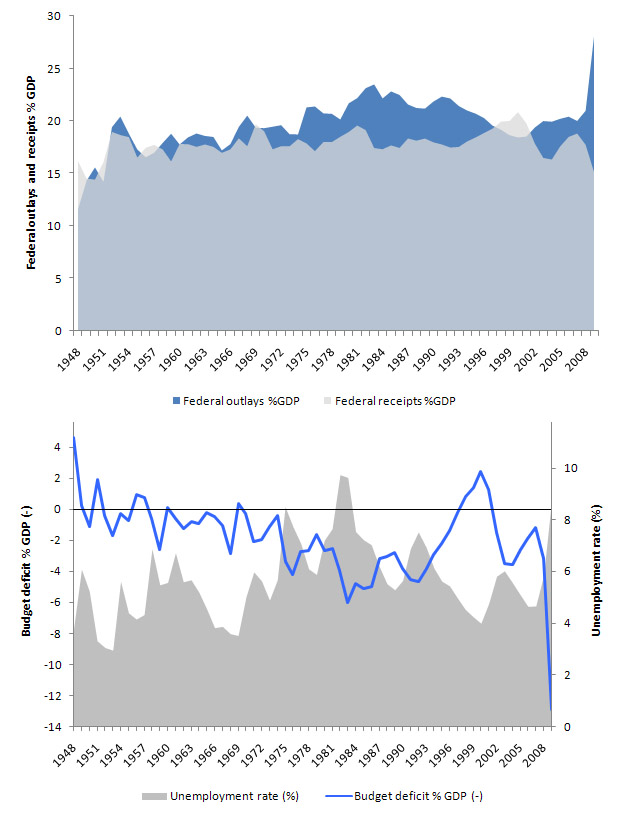

But consider my version of the graph which follows and begins in 1948 not 1997. It also scales everything to GDP and includes a lower panel showing the evolution of the federal budget balance over time alongside the unemployment rate. All data is available at US Office of Management and Budget (budget statistics) and the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (unemployment data).

Now that should set things in a totally different context. The things to note are obvious. First, Federal deficits have been the norm in the US since 1948. Everytime the federal government has tried to achieve a budget surplus (or succeeded in doing so) the economy has faltered and unemployment has risen. The deficits that followed were driven by the automatic stabilisers – falling revenue and rising welfare outlays.

Second, the Clinton surpluses only endured for as long as they did without unemployment rising significant immediately because spending in the US economy was driven by the credit-binge. This unwound for consumers around the end of 2001 and as noted above the flight back to saving resulted in a serious recession – the one before this one. This is a very similar tale to the surplus period in Australia where the conservatives were only able to maintain them for a decade because the household sector went increasingly into debt. In both countries this was an unsustainable growth strategy. We are now living through the damaging aftermath of the folly – some are more damaged than others.

Third, the deficits in the past have been inversely related to the unemployment dynamics and during the 1982 recession were large (around 6 per cent of GDP) and persisted at those levels for as long as spending had to be supported. Even so, a case can be made that Reagan should have pushed the deficits much higher given the huge jump (and persistence) in the unemployment rate. If the US Government had have been serious about maintaining full employment (US style!) then the deficits would have been much higher than 6 per cent in 1983.

Fourth, the current deficits are the highest as a percentage of GDP but include extraordinary measures to stabilise the financial system which the neo-liberal deregulation had allowed to take the world economic system to the brink. You don’t nationalise (or do the same thing and not call it that) major banks and insurance companies and help underwrite a great proportion of minor banks, without some serious outlays. (Scott: care to comment on what is included in the outlays figure which is atypical and push the deficit/GDP figure up?).

You can also see the depth of the crisis by noting the fall in revenue relative to movements in the past. The current decline in revenue is very large (as a % of GDP) and so the unusually high automatic stabilisers are driving much of the budget dynamics in the US at present.

All that makes sense to me and doesn’t scare me for a moment. The lower panel of the chart – the grey shaded part – the dynamics of the unemployment rate is what scares me. With a federal government that is not revenue-constrained the budget deficit should be even higher than it is now given the rapid deterioration in the US labour market.

Which brings me to the point of the blog? I get sent a lot of E-mails every day – many are complimentary or inquisitive and some are hostile and vindictive (more than I care think about). I also get snail mail hate letters from punters who hear me on radio or read my Op Eds and now my blog. I also get sent messages telling me that other blogs allow commentary that significantly criticises my viewpoint in a fairly personal way (that is waxing lyrical about my sanity and political ambitions).

This has been going on for years and I am used to it. If you have a public profile that is what you might expect. Water off a duck’s back!

But the hostility reflects a real ignorance and fear of new ideas and that is the worrying aspect of all the communications. It means that the levels of comprehension about how the economy actually works among the lay persons and many mainstream economists is very low. In seems that the best defence of that ignorance, is to launch a personal attack on anyone who dares to think differently (and might just know what they are talking about). The hallmark of these attacks are that all sorts of economic concepts and technical terms that sound authoritative but are not are mashed into the one incoherent wall of words.

So here are some of the more obvious elements that are used by those who are struggling to understand what is going on to discredit modern monetary theory. They will be familiar themes to regular readers but some of them still amaze me – if only for the breathtaking audacity of the vehemence that is displayed given the level of ignorance that is endemic. They are only a slice of the sort of things that are out there.

Modern Money Theorists are fanciful left-wing nutters

There is a view among the deficit terrorists that the fiscal situation for the current period depicted in the graphs above is unsustainable and that rising interest rates will choke of the capacity of the US Government to spend.

In my blog – Twisted logic and just plain misinformation I said:

… this analysis does not apply to a sovereign government. Its capacity to spend in the future is not reduced if it holds debt no matter if the economy is growing or in decline. It can never be insolvent even if its tax revenue declines signficantly. Its balance sheet can never become precarious in the same way that a household balance sheet can.

You might also like to go back to first principles – Deficit spending 101 – Part 3

So my judgement is an economic one not a political one. We had a very interesting discussion recently about the importance of that distinction in the blog – Debates in modern monetary macro … – which might be considered a useful companion to this blog.

The voters might get scared and push the US Government into cutting back spending much earlier than they should – when assessed from a modern monetary perspective which says that if the non-government sector desires to net save then aggregate demand must be supported by the government sector for output and employment levels to remain high. All throughout the period shown in my graph above – those deficits were supporting a solid private saving ratio. And it is typical for the private sector to save a proportion of their income (in aggregate).

So if the political reality sees the US Government start contracting before the non-government sector spending has risen again then they will simply worsen their already parlous situation. A fair proportion of the deficits will be wiped away as the automatic stabilisers go into reverse on the back of economic growth. The best thing the US Government can be doing is supporting spending and inspiring confidence among private investors to get capacity building spending back on track and start employing people again.

Now the recognition of the national accounting relationships which underpin modern monetary theory are not matters of opinion. These include (but the list is not exhaustive):

- That a government deficit (surplus ) will be exactly equal ($-for-$) to a non-government surplus (deficit).

- That a deficiency of spending overall relative to full capacity output will cause output to contract and employment to fall.

- That government net spending funds the private desire to save while at the same ensuring output levels are high.

- That a national government which issues its own currency is not revenue-constrained in its own spending, irrespective of the voluntary (political) arrangements it puts in place which may constrain it in spending in any number of ways.

- That public debt issuance of a sovereign government is about interest-rate maintenance and has nothing to do with “funding” net government spending.

- That a sovereign government can buy whatever is for sale at any time but should only net spend up to the desire by the non-government sector to save otherwise nominal spending will outstrip the real capacity of the economy to respond in quantity terms and inflation will result.

These concepts and understandings of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) don’t impose any political opinion at all about how the state might use these opportunities. There is nothing intrinsically left-wing or right-wing or any wing, for that matter, about these statements.

There is certainly nothing that hints of socialism or dare I mutter these words in public space – …. communism – embedded in these concepts.

The concepts are technical understandings of how a fiat monetary system – of the sort we have – operates. Modern monetary theory is different from Keynesian macroeconomics and neo-classical macroeconomics in the sense that it begins at the operational level. The knowledge framework that has been built up by modern monetary theorists did not start with some (untestable) a priori assumptions – that is, the deductive approach that exemplifies the neo-liberal text book macro.

Modern monetary theory starts with how the system works not how we assume or want it to work. On top of that a some basic insights from Kalecki, Keynes and others relating to uncertainty, investment dynamics and aggregate spending are added to the operational insights to form a coherent macroeconomics. It is a macroeconomic theory that is complete and holds up very well in explaining the revealed dynamics of fiat monetary economies.

You should always ask a neo-liberal to provide a coherent explanation of the evolution of the Japanese economy since 1990 using the principles laid out in their macroeconomic text books. So ask them to explain the years of high deficits, high public debt issuance, zero interest rates and deflation. They cannot!

So in that context, you have to separate the operational understanding that is only provided by modern monetary theorists – no other body of macroeconomics get this side of the economy remotely correct – from political statements that, say, I might make.

One could acknowledge the veracity of modern monetary theory yet still say that the government should run a surplus because they thought unemployment was a more functional way to ensure high profits (via wage discipline) than full employment. So the person would understand what will happen if the government uses contractionary fiscal policy but has a political preference for that state of affairs.

Whereas I say that I value people having work with an environmentally sustainable world above most other things and so my understanding of how the economy works tells me that the only way I can achieve those political (or ideological) aspirations (full employment) is for the government to run deficits up to the level justified by non-government saving.

You get the point – the ideological statement are entirely separable from the operational insights that modern monetary theory provides.

You might call me a left-winger because I value full employment but you would be totally ignorant if you said it because of the operational knowledge I seek to disseminate as a professor of economics.

Wanting everyone to have a job amounts to socialism

It is clear that I advocate full employment. It is also clear that one of the obvious insights that comes from modern monetary theory is that inflation can result if nominal spending chases goods and services offered at market prices.

So in that context I have for many years advocated the introduction of a Job Guarantee where the government offers a job at a minimum wage to anybody who wants one. By definition, unemployment reflects a lack of demand by the private sector for this labour. The only other sector than can provide employment with decent conditions and a living wage is the government sector.

There are many advantages arising from keeping people in employment. I have written extensively about these advantages – see this sample of my blogs and follow the pages if you want to refresh your memories.

So advocating this simple change in policy where the sovereign government uses its obvious fiscal capacity to prevent unemployment doesn’t seem to be remotely like socialism. The latter requires a major change in the ownership of the means of production in the economy to take place at the outset.

How does offering a job to anyone who wants one create large scale institutional changes in the ownership of capital? Especially when the overwhelming proportion of persons who would benefit from this approach to counter-stabilisation would be the most disadvantaged workers in our communities. How do they have any correspondence with capital at all – even in the best of times?

I might be a supporter of socialism as a political system. Then again I might not. But you won’t find anything in my publication list over many years – journal articles, books or even this blog – that will articulate that position. Nor in the writings of any modern monetary theorist that I know.

In fact, without disclosing names, some Modern Monetary Theorists would be hostile to the urging for an overthrow of the capitalist system.

Deficits are unsustainable and just cause inflation

Well we have dealt with this myth many times but it still dominates the attacks that modern monetary. Supposedly, deficits cause inflation.

I also advocate abandoning all the voluntary constraints that governments have instituted (either by law or regulation) whereby they act as if they are still in a gold standard monetary system. So I would not issue any public debt when the government is net spending (running deficits). Why would we be providing the private sector with a guaranteed welfare annuity? Especially, when the segments of the private sector that have the most to gain from using the public debt as a risk free benchmark for their profit seeking seem to hate any other form of government welfare – that is, any support for the poor or regulations to protect workers? You might like to read this blog – The problem of being a macro economist where I discuss this issue.

So in that case, I would just have the central bank “funding” the net spending – which according the deficit terrorists will be instantly inflationary.

Again you might like to refresh the statements I have made by reviewing this sample of my blogs.

It should be clear that if the economy can respond to nominal spending in real terms then most firms will behave in this way. That is, they will desire to increase real output rather than put up prices. Why? Well if they didn’t some other firm would and they would lose market share. That is one reason. There are many others.

So if there is idle capacity and idle resources that can be brought into the process of production to increase the supply of goods and services then firms will increase their deployment of those resources if they can see a realistic possibility that they can sell the goods and services. That is, they sense there is adequate aggregate demand (spending).

Fiscal deficits add to aggregate demand and provide the underpinning for firms to increase output (and employment).

At some point, nominal spending growth can clearly come up against the real capacity of the economy to expand production. That is, firms can no longer expand production because there are no idle resources or capacity left to bring back into production. At that point, the economy hits the inflationary gap – a term which simply means that the firms will start hiking prices to ration the increasing nominal spending. That is, inflation is the result.

The other way of thinking about this is that the budget deficits are too large relative to the desire of the non-government sector to save. How would we know that was the case? Well very high levels of employment (zero underemployment) and very low unemployment would tell us that we were around that point in the business cycle.

High levels of unemployment tell us that there is significant idle capacity in the economy. It cannot be inflationary for the government to use its fiscal power to provide a job to this labour – which has no private sector demand by definition. The government would not be competing for any resources at market prices.

That is another reason why I advocate the Job Guarantee as a first step because it creates enough jobs for all but at the same times introduces a nominal anchor that disciplines inflation. Once you have this “loose” full employment (see these blogs for more on this) the government can then start thinking about other expansionary policies that would improve the quality of employment and/or infrastructure provision. But the first step should be to underwrite full employment with the smallest net spending stimulus that is required to do so.

So none of that says we ignore inflation. A concern for inflation is at the heart of modern monetary theory and the policies that most of the adherents of that theoretical structure advocate.

Modern Monetary Theory is just academic

Better get a real job, son (you better get a real good one – borrowing from that fantastic song by The Cruel Sea!)

Yes, a lot of correspondence tells me that I know nothing about the real world because I just sit in a university with my hand on my …… etc (and worse). Presumably the real world is somewhere else and evades my gaze.

This is a recurring theme. As a logical construct it always amuses me. It is always mouthed by those who feel content to mindlessly reiterate the stuff they get from neo-liberal text books or to rehearse what they have read or heard others say who themselves have accessed the nonsense from the same textbooks. Where do the mainstream text book writers work? Mostly universities!

I received a particularly nasty E-mail not that long ago from a character who started by saying that he was important because he “worked behind a major bank bond trading desk” (that is, how the E-mail began). Good I thought, he/she has a job and is contributing to aggregate demand.

But one of the hallmarks of the development of Modern Monetary Theory is that the academics involved work closely with some major players in banking and the bond markets. One of the leading modern monetary theorists is on record as having created some of the largest “trades” in history.

Refer back to my earlier point – the roots of Modern Monetary Theory is at the operational level. How banks work. How central banks work. How the treasury works. The mechanisms and operations that define daily life in a fiat monetary system. The academics have achieved this understanding by working closely with our financial market friends.

You also see that some of the main commentators here work in financial markets. They understand on a daily basis how the system operates.

The collaboration between the academic and financial market modern monetary theorists has produced this body of theory. No other body of economic theory comes from that sort of collaboration.

Ideological persuasions

To make sure you characterise my political positions correctly please consult my political compass result. And if you do some exploration you will find that I am in very good company out there in the lower left-hand quadrant – along with Nelson Mandela, The Dalai Lama, Ghandi and regular commentator here Sean Carmody.

Conclusion

By the way, the overwhelming proportion of correspondence I receive is constructive and generally supportive. But a significant minority is not!

Postscript:

Blogs that seem to be interesting and those that attract less attention – I will write about this another day. Seems to be the conceptual blogs attract marginally more interest, if my statistics are accurate, than those which focus on data analysis. The differences appear to be not so much in the traffic that each page attracts but in the number of comments.

The data blogs attract less interaction. One of the reasons I presume is that the data analysis is mostly Australian and I get thousands of overseas hits each day. Anyway, I am thinking about this at present. Not that popularity is the number one aim!

After all, devoting your career to the development of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is not a sure fire way to becoming particularly popular!

Note that wrt: “High levels of unemployment tell us that there is significant idle capacity in the economy. It cannot be inflationary for the government to use its fiscal power to provide a job to this labour – which has no private sector demand by definition. The government would not be competing for any resources at market prices.”

It could be if the provision of that job competes for OTHER resources that are more scare than labour. This is one reason why a system of bids to participate as JG programs from outside the JG authority should have on-costs provided by the bidder, to bias the programs in favour of activities that are labour intensive and equipment and natural resource extensive.

Bill,

The vehemence of some of the criticism is somewhat mystifying to me, but I have been observing a similar phenomenon elsewhere in discussions on topics such as whether or not there is a bubble about to burst in Australian property prices or whether or not anthropogenic global warming is occurring or not. As in the case of monetary theory, it would seem that the core of the discussion is to get at matters of fact (whatever the degree of difficulty may be). Armed with those facts, there may be politically-inspired courses of action, but that is the second step. You would almost think that we were talking about religion!

So, it is a subject that I have been giving a fair bit of thought to of late and I am sure that there is something about the relative anonymity and lack of face to face contact in online forums that allows discussions to become more heated than would otherwise be the case. We have had flame wars as long as we have had the internet and on even less charged topics (one would have thought). For that reason, if clear messages are to be communicated, I think that tone and language are quite important. While the emails you receive may be excessively emotional, by and large cooler tempers tend to prevail here on the blog (perhaps courtesy of judicious comment moderation) and I think that this is a good thing for furthering the understanding of anyone who visits.

There is one thing I have begun to notice only in recent months and that relates to a point of language. You have often commented on the inflammatory language often used by neo-liberal critics of monetary policy: “printing money”, “monetisation”, even “Zimbabwe”. When used in this way, language can certainly distract from the central issues under discussion by means of emotional short-circuits. What I have noticed of late is your use of the terms deficit “terrorists” and deficit “nazis”. Quite apart from the fact that I tend to appeal to Hanlon’s Razor and attribute most misunderstandings of economics to cock-up rather than conspiracy, surely here you are doing exactly what you criticize others for? Just a thought.

Regards,

Sean.

Dear Sean

Good points. I would say the following.

First, if my language is immoderate then I will be more careful.

Second, I don’t attack anyone personally but always engage with the ideas that are presented. So the term deficit terrorist is generic and never said without giving a comprehensive critique of the position being presented. The criticism is only ever aimed at the ideas not the person. I never say someone is a f….n goose or whatever just because they dare to say something different. That is not similar at all to the issues I was raising in the blog where it is quite clear that the critics neither engage with the alternative ideas being presented nor understand the paradigm they are promoting sufficiently to be called informed. I also never dismiss a class of people out of hand just because they have a particular occupation.

best wishes

bill

Dear Sean

Two other thoughts to add:

(a) None of the vehement ones ever own up to who they are. I always take responsibility for my public position.

(b) Terrorism is actually an appropriate descriptor – Noam Chomsky’s definition (from the US Army Manual) of a terrorist act is “the calculated use of violence or threat of violence to attain goals that are political, religious, or ideological in nature. This is done through intimidation, coercion, or instilling fear.” The deliberate creation of unemployment is in my view a violent act against a person’s human rights. The arguments used to support the deliberate creation of unemployment (via lower deficits than are necessary) are all based on fear. Further, the government and its allies uses intimidation and coercion to deal with the unemployed. And more.

So while I will withdraw the deficit nazi terminology because that does have other connotations that I don’t want to push ever I think in this battle of ideas – that deficit terrorist is a reasonable summary of politically/ideologically assaults on human rights.

best wishes

bill

Bill,

Thanks for giving it some thought. You make good points in response and there can be no doubt at all that you are in an entirely different league from the cowards who indulge in (usually anonymous) ad hominem attacks. There is also no doubt that, in making the comments I did, I was holding you to a far higher standard. I did that because in my by now extensive reading of your blog I have come to appreciate the integrity and discipline of your writing and thought and so I know that is the right level to put the bar for you.

Regards,

Sean.

Sean,

I am with you to attribute misunderstanding of Economics by economists to cockup rather than conspiracy! Maybe Bill is attributing conspiracy because, if (lets say) a government expands its Employment Guarantee Scheme, people revolt without doing any analysis which is what terrorists do – become insecure and show some territorial behaviour?

Ramanan,

I was thinking more broadly of misunderstandings among the general public and even politicians. It does seem harder to excuse economists.

Sean.

Dear Bill and Sean,

my interpretation of the word “violent” used to be physical violence whereby one person actively hits, injures or kills someone else. So I was quite taken by surprise when the German Constitution Law Court, back in the 1970s ruled that sitting on the tram lines thereby blocking the traffic during a demonstration was an act of violence (Gewalt) even though this to me was a passive action. But as I recall the judgement the point was based on the causing of harm to others and harm was then interpreted in a broad way, eg tram and car passengers being hindered in their right to get to work on time or whatever.

Cheers

Graham

Dear Graham

My version of this is that losing ones job is a violent act – very harmful, very confronting and very shocking with often long-lived consequences (especially in a downturn). If unemployment arises from systemic failure (deficient spatially distributed aggregate demand) which I consider it does, then those who have the capacity to address that failure are guilty of inflicting this violence onto society and the individuals who make up that society. While clearly capital can alter things by investing they are not a united entity (despite conspiracy theories which suggest they act as one). But the government always has the capacity to employ anyone who hasn’t got a job. The fact they allow fear and harm to prevail by not reducing unemployment to its irreducible minimum (people moving between jobs on survey day) is an act of terrorism sourced in politics and ideology.

best wishes

bill

Dear Bill,

yes, I fully agree.

The German experience was a learning experience for me at the time and caused me to reflect quite broadly on issues of justice, fairness and a decent society. The word “Gewalt” had of course a special significance for the Germans because of the Nazi period but the lesson for me was to learn to attempt to recognise the less directly observable results of our active and PASSIVE behaviour – even if well-intentioned.

BTW, I just heard a claim (don’t know to what extent it is true although I have met 2 people who claim they have done this) that unemployed people have been moving to a country town which is more than a certain distance from the next Centrelink office because this means they don’t have to conform to the requirements. It is not that they don’t want to work but that they have given up trying to find a job and the Centrelink requirements are just too painful and cost far too much in terms of time and money. For example there is only one bus per day from this town to the town with the next Centrelink and one return bus. So the round trip takes all day. They know their chances of getting a job are nil anyway even if they lived in the town with Centrelink.

Cheers

Graham

Dear Sean,

Great post about Hanlons Razor. The victims families of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings will be very relieved when they find out it was all just a cock-up rather than a calculated act of mass murder.

And while we are at it lets assure the victims of the stolen generation that it was all just a simple cockup…or that the White Australia policy was just a simple cock-up rather than a blatant ploy to wipe out the Aborignial culture.

Well done Sean – great post I’m so glad you cleared it all up for us.

I know this is a very old post of Bill’s but I’m always accused on here of having a very basic underlying misunderstanding of MMT and so I thought I needed to revisit the groundwork. Two things are made very clear – the desired end result Bill suports “I value people having work with an environmentally sustainable world above most other things” is the same as mine (and most peoples) and as Bill points out MMT is just a framework to understand how that aim (or any others) might be attained. Then Bill says “and so my understanding of how the economy works tells me that the only way I can achieve those political (or ideological) aspirations (full employment) is for the government to run deficits up to the level justified by non-government saving.”- This is where I feel my understanding dissolves. It is left entirely open whether “the level justified by non-government saving” is zero (if a wealth tax were to keep the amount of accumulated savings constant over time) or whether savings are to be allowed to accumulate indefinately. To me the practical consequences of having accumulating savings appear overwhelming and certain to thwart any positive efforts made by the government spending. Is it an MMT position that enlarging the global pot of savings from say £1T to say £100T will not necessarily increase the size and political influence of the FIRE sector and oligarchy and otherwise distort the economy and society? If such an increase in the global pot of savings is predicted to have no influence, am I uniquely stupid in falling into the misconception that it does and is that why MMTers do not feel the need to explain how it has no influence? If MMTers do also recognize the importance of having a limit to the global pot of savings then I don’t understand why MMTers don’t say deficit spending has dual constraints- not inducing consumer price inflation by overwhelming capacity and also not creating an undue burden of savings. I know I have asked this before and many people have made an effort to answer but the answers have all totally contradicted each other to the extent that I get the impression that the issue is the “emperors new clothes” of MMT.

People have said- the size of the financial services sector and the power of the oligarchy is entirely uninfluenced by the scale of the wealth it has under management- I say that if true then that is one of the most amazing and counterintuative results I have ever come across in any field and deserves much more exposure.

People have said- limiting savings is a purely political not economic issue- I say if the consequence is economic catastrophe then it is just as much an economic issue as hyperinflation is an economic issue.

People have said- when the time comes MMTers will come up with adequate measures to constrain the financial services sector such that a small benign financial services sector will handle an ever increasing mountain of wealth and keep it from distorting the economy- I say that how can such a vague claim to be able to hold back the tide be the basis of advocating a course of action.

People have said- when the time comes MMTers will come up with adequate measures to constrain the financial services sector such that a small benign financial services sector will handle an ever increasing mountain of wealth and keep it from distorting the economy- I say that how can such a vague claim to be able to hold back the tide be the basis of advocating a course of action.

stone, see Warren Mosler’s proposals for reforming the system. Also check out Michael Hudson’s extensive work on taxing economic rent, and the work of William K. Black, former federal regulator and forsenic expert on financial fraud and predation. Both Hudson and Black are professors in the economics department of the University of Missouri at Kansas City and blog at New Economic Perspectives at Kansas City. The economics department of UMKC is MMT-oriented and it represents itself as the Kansas City School, with the blog offering economic analysis and policy advice based on the operational realties of the modern fiat system.

Marshal Auerback, who blogs at New Deal 2.0, also writes about this issue from a variety of angles. See, for instance, The Wasteful War Machine, Where Have All the Investigators Gone?, Will We Have to Blow Up a Continent (Again) Before We Stop Wall Street?, Attack the Disease, Not the Symptoms, and In the Age of Systemic Risk-A Proposal for Genuine Financial Reform.

So I think that as you broaden your acquaintance with MMT, you will find that MMT and its close allies not only have these issues adequately covered but also are in the forefront of financial reform and operationally-based economic policy-making in the US. Their recommendations also apply generally in monetarily sovereign countries operating with modern fiat (nonconvertible floating rate) currencies.

It appears to me that you are confusing savings in the economic sense of income not taxed or consumed with economic rent in the sense of revenue from non-productive sources, i.e., land rent, monopoly rent, and financial rent. Consumer savings are not the problem, economic rent is. As Michael Hudson notes, it must be disincentivized through appropriate legislated policy and strict regulation, oversight, and accountability.

The political objectives of many MMT’ers that are writing on the blogs is optimal capacity utilization, full employment and price stability, distributed income, and sustainable productive investment sufficient to grow the economy proportional to population, in an environment where government allocates a portion of national resources to advancing public purpose. This involves removing inefficiencies resulting from non-productive activity that is essentially rent-seeking. Excessive executive compensation would fall into this category, for instance, as well as money shuffling instead of production. MMT’ers also take on issues like central bank independence and institutionalizing consumer debt, thereby creating what Hudson calls “debt peonage” as the driver of the economy.

Tom Hickey, I was referring to the sites etc you mention when I said “People have said- when the time comes MMTers will come up with adequate measures to constrain the financial services sector such that a small benign financial services sector will handle an ever increasing mountain of wealth and keep it from distorting the economy- I say that how can such a vague claim to be able to hold back the tide be the basis of advocating a course of action.” -the tide is a totally uneccessary consequence of the expanding currency mindset that comes about from being entirely subservient to the idea that the global pool of savings has to increase year on year, decade on decade. How and who can distiguish consumer savings from “economic rent”? Basically if a friend of MMTers accumulates wealth it is worthy whilst if someone else does it it is “economic rent”.

How and who can distiguish consumer savings from “economic rent”?

Defining economic rent is really pretty simple in terms of productive and non-productive. Most consumers, “the little people” in neoliberal terms, would not be involved in economic rent-seeking, and they would only be taxed on land rent if subject to it. Most “consumers” would benefit because taxing economic rent would eliminate the need for much other taxation, and they would be left with more discretionary income for consumption and saving for a rainy day, retirement, anticipated expenses like their children’s education. The problem with “savings” is not consumers savings which are eventually consumed. It is funds gained from economic rent that go toward more rent-seeking. That is the province of the “the big guys,” not “the little people.” The “big guys” are what P. K. Sarker and Ravi Batra calle “the acquisitors.” Their primary motivator is wealth solely for the sake of acquiring more wealth. The “little people” would simply like to live a more commodious life and look forward to a better life (standard of living) for their children.

I have one major problem with MMT.

MMTers condemn mainstream economists for relying upon monetary policy as the principle means of managing the economy by maintaining an unnecessarily high level of unemployment, whilst on the fiscal side aiming to “balance the budget” over the economic cycle. They base their critique upon moral grounds:- anything less than full employment, they say, offends against social justice and equality, benefits the rich at the expense of the poorest, and gives rise to a whole train of side-effects which damage society. They ascribe not just what they regard as stupidity to the mainstream, but deliberate inhumanity. One way and another they work up quite a head of moralistic steam.

Well and good, so far as polemics goes – and some at least of the strictures may well be justified. But how comes it that MMTers are totally silent in regard to the fact that the private banks are permitted to create nearly all of our money, as debt, on which they collect the interest? This is a completely unjustified public subsidy which amounts, In UK for example, to some £100 billion per year added directly to the banks’ profits. Like any subsidy it is redistributive, and this particular one is from the less well-off to the most well-off. Yet we hear absolutely no discussion let alone condemnation of this within the MMT community.

A movement is slowly gathering pace in favour of radical monetary reform, aimed at putting an end to this unwarrantable subsidy to the richest corporations in our society, as well as to its many grossly distorting effects (such as fuelling credit bubbles and speculation, particularly in the property market). But MMTers appear to have chosen to shut their eyes and ears to it. How is it possible to inveigh against the moral unacceptability of causing people willing and able to work to be denied jobs whilst at the same kind apparently finding it entirely acceptable (as not even being worth a comment) that private corporations should enjoy the privilege of creating our money, in the form of interest-bearing debt?

The (deliberate?) blindness is all the more incongruous in light of MMT’s continually emphasizing that the sovereignty of the state is a defining feature of MMT doctrine. Yet in an allegedly sovereign state such as Britain the state in actuality creates and issues less than 3% of the country’s money, having surrendered to the banks the power to create and to profit from all the rest. And how does MMT reconcile these glaring contradictions? Simple:- by ignoring them.

Isn’t it time MMT’s exponents started showing some interest, at least, in this crucial question? Until they do MMT will remain, for me at least, just a mildly-diverting cockshy. As a non-economist its technical aspects hold little interest for me, no more than do constant sectarian squabbles over the relative merits of rival economic dogmas. The same, I’d suggest, goes for a large majority of the informed public. Time to wake up?

Robert, I discovered MMT around 2003 while looking for counterarguments to “inflationista” white papers that friends were

sending me. Let me say that you are categorically wrong in your statement MMT theorists do not recognize and have not called out the evils of rentier income, the banking sector, wall street, etc. Dr. Randal Wray has railed against it on neweconomicperspectives.blogspot.com. Warren Mosler has talked about how the financial sector needs to return to the model used in the 1970’s and I quote him “The financial sector is a brain drain.” He’s been saying this for years. Also, Warren was in favor of letting all of the banks fail during the crisis but with 100% government insured deposits.

Robert, historically there were two models of banking. The one that you cite is the Anglo-Saxon one which relies on short-term interest gains. There is also another model of banking which has been traditionally used in continental Europe and Japan. Well, not any more but only because Wall-Street has taken over at this point in history. This second model of banking has completely different groundings and it is enough to say here that it is based on equity cross-holdings (instead of loans) with strong participation and role of government.

“Like any subsidy it is redistributive, and this particular one is from the less well-off to the most well-off.”

Really. Who owns most of the bank shares and what do they do with the dividends?

Plus with CGT at 18% (unless you live in Monaco when its 0%) and Income Tax marginal rates over 90%, I think we have a far more pressing issue of redistribution built right into the entire UK tax system.

I’m afraid that you’ve listened to too much of the 100% reserve propaganda people and not got enough perspective on the real issues.

Now if you were arguing, as some do here, that 100% reserve is a better way of regulating the banks because it is simplifies their operation and makes them easier to liquidate when they burn up their capital, then I could go with that.

Robert and Neil Wilson, I very much think that 100% reserve banking is an essential reform.

In answer to Neils “Really. Who owns most of the bank shares and what do they do with the dividends?” – as far as I can see pension funds hold much of the bank shares, the profits are mostly retained by the banks with only a token fraction paid out as dividends. The profits not paid out as dividends are creamed off by high frequency trading conducted by investment banks and hedge funds aka the oligarchy. Also many top bankers get pay of a level so excessive that most of it goes straight into savings (eg >£4B in city bonuses in London this year).

Tom Hickey-“Defining economic rent is really pretty simple in terms of productive and non-productive.”

I really can not get my head around how you would do this in practice. Would a group of MMT officials sit in an office and vet every item of investment and make a pronouncement as to whether they considered it Kosher? How much work would that entail? Wouldn’t that give extraordinary power to that group of MMT officials? To me they would be assuming the role of soviet central planners but with the extra spin that people were making and loosing billions of dollars on the basis of the decisions they made as well as “merely” the whole functioning of the real economy resting on their decisions.

@stone

Saving is the same as voluntary reversible taxation. It means that general taxation can be lower for the rest of society in normal times.

It’s spending that causes problems.

Neil Wilson: Saving in a giro bank might be similar to voluntary reversible taxation. Saving in a normal bank account most certainly is not. The money that caused the 2008 crisis was fed into by the Yen carry trade that utilized savings in normal bank accounts. Anyway by “leakage to savings” I was including all of the wealth that had slipped from the pool used for consumption into the pool used purely for “building wealth”. It is that latter pool of money that whilst necessary for the economy also needs to be kept from expanding in order to retain the scarcity value of money for investment so that wise investments are made that allocate resources in the best way for the real economy. If the government ensures that the pool of savings constantly increases then that leads to an economy wide ponzi effect for asset prices and that results in a deranged economy.

stone,

No it doesn’t and you’ve no evidence it does.

Bill’s written on 100% reserve banking and we’ve had a few discussions here as well. Can’t recall exactly when, but maybe someone can find it. Suffice it to say–and the details are provided in those discussions–that 100% reserve banking changes virtually nothing. It’s regulation and oversight that are the most important. And as Tom noted above, MMT’ers are at the forefront of research in this regard. Anyone who isn’t familiar with this literature isn’t really familiar with MMT.

Neil Wilson “No it doesn’t and you’ve no evidence it does.” -which bit is this about? Are you saying that in the absence of expanding currencies there could be asset price inflation or are you saying that asset price inflation does not equate to ponzi finance or are you saying that ponzi finance does not harm the working of the economy?

stone: I really can not get my head around how you would do this in practice. Would a group of MMT officials sit in an office and vet every item of investment and make a pronouncement as to whether they considered it Kosher? How much work would that entail? Wouldn’t that give extraordinary power to that group of MMT officials?

Have you ever seen the IRS book of regulations? It is thick and detailed, and it takes a CPA to understand and interpret it. The tax authorities have no trouble defining what is taxable and what they say goes. All Congress has to do say, productive and non-productive with a few guidelines, and IRS will take care of the rest, just as they do now. Right now, the tax code is loaded in favor of privileging economic rent and taxing incomes, because the wealthy get the economic rent that is not taxed or taxed lightly, and workers get wage and salaries that get taxed heavily. This is the way the wealthy get around the progressive income tax.

Tom Hickey-So you are wanting the congress to rise above the current lobbying and instead base their decisions on their ability to forecast what amounts to economic rent? I just personally think a wealth tax would leave a lot less wriggle room and be a lot less likely to distort against beneficial investments that were not recognized as such due to prejudice or a like of foresight.

Neil Wilson “No it doesn’t and you’ve no evidence it does.” -which bit is this about? Are you saying that in the absence of expanding currencies there could be asset price inflation or are you saying that asset price inflation does not equate to ponzi finance or are you saying that ponzi finance does not harm the working of the economy?

stone, the problem is not asset prices per se, it is leverage. Ponzi finance is not based on asset prices being “too high” but rather on the debt service supporting the prices being unsustainable. Prices that are “too high” eventually correct, and people who invested unwisely loose money. That doesn’t affect the economy if they are 100% invested. This happens all the time in various markets without undue disruption. But when people who are highly leveraged drive up asset prices, then the house of cards collapses and debt-deflation takes hold. If there are lot of such people, then there is a real problem.

Tom Hickey “the problem is not asset prices per se, it is leverage. Ponzi finance is not based on asset prices being “too high” but rather on the debt service supporting the prices being unsustainable.”- I agree that leverage makes the situation worse but I disagree about the situation being OK were it not for leverage. If it were not for currency expansion, there would not be asset price inflation- asset price inflation means that even those making entirely random investments which do not yield real returns nevertheless gain due to the ponzi process. The price corrections you talk about would bring their gains back down to zero in the long run were it not for asset price inflation. If asset price inflation is greater than consumer price inflation (and that is the way things are set up) then those who start off with the most assets get a proportional transfer of wealth courtesy of the government and at the expense of everyone else. That is the ultimate form of “economic rent” if you ask me.

stone: So you are wanting the congress to rise above the current lobbying and instead base their decisions on their ability to forecast what amounts to economic rent? I just personally think a wealth tax would leave a lot less wriggle room and be a lot less likely to distort against beneficial investments that were not recognized as such due to prejudice or a like of foresight.

We are discussing optimal policy based on operational principles. Politically, there is virtually no practical possibility of either taxing economic rent or”wealth” given the present system, unless the legislature would pass effective campaign finance/lobbying reform and locking the revolving door, and even then the US Supreme Court has limited what Congress can do in this regard, so it would take a constitutional amendment. Neither taxing economic rent nor a wealth tax are going to be enacted while the wealthy retain control. And if they should lose control, then MMT’ers should be ready with a comprehensive proposal for optimal economic policy.

The advantage of taxing economic rent rather than “wealth” is that productive investment is not taxed under this proposal, but non-productive extraction is. Presuming a capitalistic system such as the present one, then this is a reasonable solution. The objection to a wealth tax consistently is that it stifles incentive for productive investment. A proposal to tax economic rent avoids that objection, which is a reasonable one. Productive investment is necessary for incomes/employment/demand. What I am arguing is that eliminating parasitism is an ingredient of an MMT-based proposal for reform.

That is the ultimate form of “economic rent” if you ask me.

I would agree that a great deal of asset appreciation falls under economic rent, since it is non-productive. That should be taxed away under this proposal. In a system that controlled leverage abuse, a lot of asset price run up would not occur. Most of the gains from leverage abuse are non-productive and would be taxed away, and this would disincentivize abusing leverage. Those who did continue to abuse it would suffer the tax consequences. Ponzi finance is an abuse of leverage by definition.

But asset markets are not a problem in themselves and they perform useful functions when they operate to determine spot and forward prices and provide liquidity, instead of being used for wealth extraction through parasitism. Leverage is also an economic benefit when used reasonably to draw demand forward. There would not be much of a housing market without mortgages, for example.

Tom Hickey “The objection to a wealth tax consistently is that it stifles incentive for productive investment”- The last thing I would want would be to stifle productive investment. To my mind the true measure of whether an investment is productive is whether it pays a return. A wealth tax (ie a tax on the value of any asset such as stocks, real estate, cash etc) would mean that people would vue the value of the asset as a cost and the return it paid out as the benefit when deciding whether to buy it. To my mind that would incentivise productive rather than ponzi finance in contrast to the current system. If I think of a local example of productive investment, I think it would have been encouraged by a wealth tax system- a local start up got £1M per year for nine years to convert an invention into a £100M profitable business that was sold on to a larger company. Under a wealth tax the venture capitalist invenstors would only have had to pay tax on the value of the start up which was pretty minimal before about the 7th year of its life. When they sold it on for £100M they would have had no capital gains tax to pay. My understanding is that a wealth tax would reduce asset prices and greatly increase the yield from productive assets. It would decimate the price of non-productive assets such as gold.

100-percent reserve banking and state banks

See the comments, too. JKH weighs in extensively. This post is a gem.

Scott Fullwiler Suffice it to say-and the details are provided in those discussions-that 100% reserve banking changes virtually nothing.

Well done. You just confirmed all my worst suspicions about MMTers. You’re living in cloud-cuckoo land.

Joseph Schumpeter (is that a swear-word here btw?) among others was of the opinion that it was the single feature of modern capitalism that most clearly distinguishes it from its predecessors or any other system. If you honestly believe that the power to create money “changes virtually nothing” I really can’t begin to imagine what sort of world you’re living in.

bubbleRefuge Let me say that you are categorically wrong in your statement MMT theorists do not recognize and have not called out the evils of rentier income, the banking sector, wall street, etc.

I made no such statement. Nor so far as I’m aware (but please correct me if I’m wrong) has Dr. Randall Wray been anything other than silent in regard to fractional reserve banking. Warren Mosler (as I know at first hand) has no interest in the matter – he refuses to see it as a problem.

As I think do you, since you haven’t connected my description with what my description was actually about.

I accuse MMTers – all of them, I’m beginning to think – of consciously shutting their eyes to a flagrant abuse. Worse than that, your writings sanction it (see Scott Fullwiler’s comment).

So much the worse for MMT.

The last thing I would want would be to stifle productive investment.

Then we likely on the same page and the kerfuffle is semantic.

I would prefer to see an economy in which minimal consumer saving is required because social programs provide the necessities of life, including education, health care, pension, etc., and fiscal policy incentivizes productive investment and income from productive contribution, in which I would include everything related to primary use in production. Secondary use (speculation) I would tax as essentially non-productive although not all of this is necessarily parasitic. I would tax away the parasitic in order to completely disincentivize it. Most of this would apply only to the top tier. I would also use taxation/fees/fines to eliminate negative externalities and reduce negative behaviors.

If we want to create a vibrant capitalistic economy, they we need to incentivize both productive investment/supply and productive employment/income/demand and disincentivize the non-productive. Presently, a great many if not most of the incentives are reversed, leading to chronic imbalances distributional problems, and unnecessary shocks that create disruption and make life worse for a lot innocent people, while the perps go unaccountable. This is not all that difficult to understand and change.

According to MMT, A monetarily sovereign government as monopoly currency issuer has the sole prerogative and corresponding sole responsibility to provide the correct amount of currency to balance spending power (nominal aggregate demand) and goods for sale (real output capacity). If the government issues currency as nongovernment net financial assets in an amount that results in effective demand in excess of capacity, demand will rise relative to the goods and services that the economy can supply, and inflation will occur due to excess demand relative to supply. If the government falls short in maintaining this balance, recession and unemployment result, due to insufficient demand relative to supply. The government attempts to achieve balance through fiscal policy (currency issuance and taxation) and monetary policy (interest rates), based on analysis of data in terms of sectoral balances. Part of this involves making sure that productive investment is growing the economy proportional to population growth and distributing it demographically. Government also has to oversee banking, shadow banking, and other aspects of the financial sector in order to prevent imbalances from occurring. Congress needs to provide tools for this, and make sure they are being used properly.

I would revisit the indexing of inflation and look at including asset inflation in addition to CPI and PPI. The GFC developed in part because the Fed under Alan Greenspan missed this, and the Fed under Ben Bernanke is trying to stoke asset prices again, prolonging the unwinding of the financial cycle at the risk of more debt bombs exploding.

Sergei Robert, historically there were two models of banking. The one that you cite is the Anglo-Saxon one which relies on short-term interest gains. There is also another model of banking which has been traditionally used in continental Europe and Japan.

Thanks for that comment, and I find it interesting that you term it “the Anglo-Saxon model of banking”. That lends a bit of healthy perspective.

But the Anglo-Saxon model was not predetermined to become what it did: there were in earlier times instances of honest models of banking before inordinate greed took over. The turning-point was the chartering of the Bank of England in 1694, for the express purpose of printing what were for all practical purposes counterfeit banknotes bearing the fraudulent words: “The Bank… promises to pay the bearer on demand the sum of —“, in the full knowledge that the promise could not be honoured if more than a certain proportion of the notes were presented for redemption at any one time. Whenever this threatened to happen the Bank suspended its promise, and was never taken to court for doing so. Maybe people were less litigious in those rumbustious times and so long as you were brazen enough you could get away with pretty-well anything – so long as you were a gentleman of course (if you were a villager you were hanged for stealing a sheep).

Robert,

That was then, this is now.

What is promised to the bearer of a government note now? The answer is : nothing other than the use of it to extinguish a tax liability.

Fractional Reserve Banking is a canard of the recent Austrian School Renaissance. It may have had a little relevance when notes could be redeemed, but it has zero relevance now.

The answer to the entire problem is to take bread and butter banking and turn it into something like a public utility through regulation.

Robert,

Please prove via appropriate balance sheet manipulations that 100% reserves stops anything. Good luck.

Robert @7:19: To state it a bit differently, the point is that 100% reserves doesn’t alter whatsoever “the power to create money.” Sure, the power to create money is about as important as it gets, but it existed long before capitalism did. And I’m a big fan of Schumpeter, by the way.

Tom Hickey “I would revisit the indexing of inflation and look at including asset inflation in addition to CPI and PPI.”-Our objectives may be the same but there is an overwhelming difference between our positions because you (and all MMTers) want currency to expand and I am saying that for capitalism to meet your objectives it is vital that there is no expansion of the currency. If as you say, you were to adequately include asset inflation in your indexing and aimed for a zero rate of all inflation, then we would be in aggrement as that would equate to a trend towards balanced budgets followed by balanced budgets from then on.

You say that the currency has to expand due to population growth. The population growth in the UK and USA is due to migrants forced to migrate due to the distortions caused by the expanding currency system. If it were not for expanding currencies it would not be possible to trade USD for real goods on a long term basis with the USD being hoarded by the elite. That would mean that money from international trade would have to be spent (eg by paying for higher wages, education etc). That would reduce both the economic migrations to places such as the USA and UK and also the poverty that leads to rapid population growth in impoverished nations.

You say that adequate fiscal stimulus is dependent on having an expanding currency. I totally contest that. Current government spending is about 80% covered by taxation. If that taxation was shifted from the many different forms it is in now to a wealth tax (a tax on asset value applied equally to all assets eg stocks, real estate, cash etc), there was a modest pay cut for the highest paid public sector workers and a citizen’s dividend was paid to everyone, then a balanced budget with no increase in the burden of taxation might give a level of fiscal stimulus that filled the capacity of the economy.

Jeff65 “The answer to the entire problem is to take bread and butter banking and turn it into something like a public utility through regulation.”

What does that vague phrase actually mean? Does it, for instance, mean that private corporations would no longer be legally permitted to create money in the form of debt? Does there exist somewhere in MMT-land a fully worked-out proposal for how that aim might be accomplished? If so, I’d be genuinely interested in knowing where I can read it.

As you may or may not know, such fully worked-out proposals do exist in the outside world – several of them.

Scott Fullwiler “Robert @7:19: To state it a bit differently, the point is that 100% reserves doesn’t alter whatsoever “the power to create money.” Sure, the power to create money is about as important as it gets, but it existed long before capitalism did. And I’m a big fan of Schumpeter, by the way.”

You seem not to have taken on board that the issue here is not the power to create money (which, of course, has existed since human societies started using cowrie-shells or whatever as money). The issue is who ought to have it – elected governments or privately-owned profit-seeking corporations, drawing interest from every cent of it?

MMTers inveigh passionately against the iniquities of so-called neo-liberal (ie conservative, right-wing) governments. Yet at the same time you view with complete equanimity the privatisation of our money-supply for private profit. Beats me!

!00% reserves mean that deposits remain the property of the depositors and are not legally permitted to be taken onto a bank’s balance-sheet and thereby be taken into and treated as part of the bank’s capital. So balance-sheets, for your information, don’t come into the argument. It also means that no loan (a credit) may be made without being balanced by an exactly equal debit elsewhere – in other words, a bank can only loan money it already has or is able to borrow. The bank is thereby deprived of the power to create one single cent out of thin air.

And btw your characterization of FRB as a canard of the Austrian School merely confirms my suspicion that you MMters have blinded yourselves to reality. Offhand I find it difficult to think of any group more viscerally hostile to the Austrian School than the American Monetary Institute; they are in the forefront in the US of the campaign for monetary reform through abolition of FRB.

More and more MMT seems to assume aspects of a monkish cult, to my mind.

Jeff65 “The answer to the entire problem is to take bread and butter banking and turn it into something like a public utility through regulation.”

On the face of it this sounds as if it has some very serious implications. If publicly owned banks had unlimited funding and could decide who and what to fund, then what is the conceptual difference between that and a Soviet central planning set up. The problem with giving “public utilities” the power to decide what should and should not be funded is that they always seem to choose grand “best of the best” projects rather than meeting everyday needs. Think of the Concord supersonic passenger plane project we had in the UK thanks to such a system of funding, also the Appolo Moon landings and basically the whole Soviet Empire- nuclear bombs, helicopter gun ships, space exploration but a fairly crappy existence for most of the “little people”.

Robert . . . just as I suspected, you have no clue how deposits or banking works. Go see JKH’s comments in the link Tom provided. He demonstrates rather clearly my point.

stone: Our objectives may be the same but there is an overwhelming difference between our positions because you (and all MMTers) want currency to expand and I am saying that for capitalism to meet your objectives it is vital that there is no expansion of the currency.

Agreed. As has been explained, your approach is through the quantity (stock) of money and the MMT approach is through sectoral balances of GDP (flow). What you are arguing essentially is a fixed rate monetary system and MMT is arguing a flexible rate system. The MMT literature shows amply how adhering to the former hobbles the ability of economic policy to deal with domestic problems like unemployment since it is keyed to inflation. MMT claims to be able to generate an economic policy that results in full employment (less frictional) at optimal capacity utilization, along with price stability.

The way that MMT works is through adjusting flows through fiscal policy – currency issuance through targeted government disbursements and currency withdrawal through targeted taxation. There is also a coherent macro theory to back it up that is based on operational reality.

I don’t see any comparable economic theory on the table that compete with this credibly.

stone @ 19:42

Well, we agree on this anyway. As a libertarian of the left, the last thing I want is government controlling the economy top-down and that is what exclusive state banking would amount to. There needs to be a healthy balance of public and private to keep both in check.

Tom Hickey, I had to do a google search to try and work out what you meant by “What you are arguing essentially is a fixed rate monetary system and MMT is arguing a flexible rate system. The MMT literature shows amply how adhering to the former hobbles the ability of economic policy to deal with domestic problems like unemployment since it is keyed to inflation.”.-I really don’t know what you mean. I most certainly am not arguing for the exchange rates of different currencies not to be free floating if that is what you somehow thought. -All I am arguing for is for the MMT spending side of things with free floating currencies to be combined with a balancing wealth tax. As far as MMT claiming to be able to maintain price stability, it has been made very clear that you do not include asset price stability in that.

stone, you want to limit the quantity of money by some mechanism that establishes a standard. That is effectively a fixed rate system, since the “right” quantity is determined by an imposed standard. The domestic effect of this is comparable to a convertible fixed rate currency, where the government (consolidated treasury and cb) is constrained in issuance based on the fixed limit. This is what the balance budget advocates are advocating. The point of fixed rate systems is to control inflation ( in your case, specifically asset inflation).

The point of MMT’ers preference for a flexible system is that controlling inflation through arbitrary standards results in unemployment or unsustainable consumer debt for countries that are not net exporters and whose citizens desire to save a portion of their incomes. An imposed standard, either internationally through fixed rates or a domestic rule mimicking this, restricts a government’s inability to adequately address unemployment through fiscal policy by running deficits. Unemployment becomes a tool to control inflation. What MMT says is that government should target both employment and inflation through altering flows, which are controlled fiscally by issuance and withdrawal (taxation). These can be tightly targeted, so that funds are put in where they are needed and taken out where they are collecting and stagnating.

When firms take the stimulus funds to run up their income statements and balance sheets, they government has to step in and address that with, e.g., higher corporate taxes on money that is not productively invested (spent). Again, the banks were bailed out so they would start lending again, but instead, they took the money and ran off to leverage it, rebuilding their balance sheets for free and continuing to pay outsized compensation. That should also be taxed away to discourage such behavior. This is all about incentivizing productive investment, which is necessary for lifting income that generates consumer demand and permits delevering to stave of debt deflation, and disincentivizing economic rent, which is parasitical. As Bill’s post points out, business got a free lunch from the stimulus. That is basically monopoly capital resulting from earnings in excess of productive contribution.

You assume that by establishing the correct standard for controlling quantity, an economy will run eternally at a happy equilibrium. You would have to work out the numbers to show that and also defend the assumptions on which the model is based.

Tom and others,

Clarifying what I mean by “public utility”:

Currently the government grants permission for banks to create money when they make loans, making a private – public partnership. Because this is a government granted monopoly, it should be heavily regulated whether privately or publicly owned and should be about as interesting (in terms of complexity) as the Postal Service.

The banks’ duty is to make loans to creditworthy customers (loans that have a high likelihood of being repaid in full.) To ensure the banks fulfill their duty, the banks bear the full risk of loss on loans they make.

In exchange for this the banks receive the interest payment, which also serves as a brake on the demand for loans.

When viewed this way, it is easy to see where everything has run off the rails. Banks no longer bear the full risk of loss on loans they make and because of this the incentive to loan only to creditworthy customers has been lost. Enforce this one simple thing and the mess we find ourselves in now would not have happened.

Tom Hickey, I am disappointed that rather than facing up to the points I made you have found it more comforting to claim that I was advocating a fixed currency exchange rate and have argued against that. I agree that fixed currency exchange rates are not good and appreciate that it is very much in all of our comfort zones to argue against them.

If any relevance to anything I have ever said can be extracted from your @6:54 comment it is “controlling inflation through arbitrary standards results in unemployment or unsustainable consumer debt for countries that are not net exporters and whose citizens desire to save a portion of their incomes.”- as I have always maintained my whole point is that it is essential that the macroeconomic set up makes no provision for “citizens desire to save a portion of their incomes” on an aggregate basis. Obviously people and corporations need to save when they can so as to cover expenses they later need to cover for- BUT in a sane world, for every person or corporation saving there will be another drawing down on savings previously accumulated. Precisely what I am arguing against is the expansion of the currency to accommodate a decade on decade, generation on generation, build up of global savings that are never spent and yet cost us dearly to manage and distort the economy.

With regard to consumer debt- some (the wealthiest) have access to consumer debt. Unlike governments, consumer debt can not be rolled on from one generation to the next- so one set of wealthy US citizens may die off with debts BUT the level of consumer debt can not increase exponentially generation after generation. It is the long term exponential increase in savings which means that a crisis will inevitably be forced so long as the system attempts to cater for it by expanding the currency.

stone, savings typically come at pretty stable share of GDP. They have been stable over different time periods and in different countries. However the underlying dynamics of this process is way too complex in order to be able to say that savings should be equal to this percentage of income and nothing more. There are various factors like position in the business cycle, demographics, technological trends and fashion, etc. which can influence any particular outcome in savings. I am sorry that you do not understand this point and keep on pushing some type of fixed rule arguing that savings above this level are bad. The only result that your rule is going to achieve is to fight the private sector. It can be a viable approach but I am sure that all MMTers, despite their strong believe in the government, will stand behind private sector desires and freedom as primary sector fulfilling long-term economic growth. Government is only to support private sector and not to fight against it. If you have a believe that your approach is a better one there is no contradiction with MMT as long as you have broad consensus behind it and also make sure that you mitigate any adverse effects of such policy. Again, there is nothing that contradicts MMT here and you simply appeal to political views of different people. Political views can hardly be reconciled if they are way apart.

Scott Fullwiler: “Robert . . . just as I suspected, you have no clue how deposits or banking works. Go see JKH’s comments in the link Tom provided. He demonstrates rather clearly my point.”

We may as well face the fact that we’re never going to get to the nub of this. I’m not an economist and to me JKH’s comments in that link are more or less totally impenetrable.

However, in my trawling through some amongst Bill’s voluminous writings I did come across the following:-

“When a bank makes a $A-denominated loan it simultaneously creates an equal $A-denominated deposit. So it buys an asset (the borrower’s IOU) and creates a deposit (bank liability). For the borrower, the IOU is a liability and the deposit is an asset (money). The bank does this in the expectation that the borrower will demand HPM (withdraw the deposit) and spend it. The act of spending then shifts reserves between banks. These bank liabilities (deposits) become “money” within the non-government sector. But you can see that nothing net has been created.”

This is, frankly, twaddle. Or, to put it more politely, tautology.

Of course nothing net is created when it is a self-fulfilling outcome of double-entry bookkeeping (the conventions of which like all conventions are entirely synthetic, that is to say without independent veracity external to the particular system from the operation of which they derive their sole meaning) that all entries on one side of the ledger shall be balanced by equal entries on the other. That’s bookkeeping, but it isn’t logic.

If I take a loan from a bank to buy a car the amount of the loan is added to my current account. No other account is debited; instead (in accordance with bookkeeping conventions) the increase the bank makes in my current-account balance is booked as an added liability of the bank, while my IOU for the amount by which my current account has been increased is booked as an addition to the bank’s assets. Surprise, surprise – the two net out.