In my commissioned research activities, which are separate from the basic academic research that occupies…

Rates go up again down here

This time last month I was trying out the mobile office concept up the coast (see blog). The experiment was a success but the blog I wrote that day coincided with the decision of the Reserve Bank (RBA) to hike short-term interest rates again, which I considered to be a mistake. Exactly, one month later, the RBA is at it again however I am in Newcastle and there is no surf! The RBA announced today, quite predictably, that the policy rate will rise by 0.25 per cent which will push mortgage rates above 7 per cent. Our greedy private banks get another free ride out of this and the decision confirms that the crisis has not really changed the neo-liberal economic policy dominance. Inflation targeting which uses labour underutilisation as a policy weapon and fiscal surpluses which further drag the economy down – are well and truly entrenched. Spare the thought.

In the statement from the RBA Governor we read that:

The global economy is growing … [but growth] … is still hesitant in the major countries … [with] … ongoing excess capacity. In Asia, where financial sectors are not impaired, growth has continued to be quite strong, contributing to pressure on prices for raw materials …

Australia’s terms of trade are rising … [and] … output growth over the year ahead is likely to exceed that seen last year, even though the effects of earlier expansionary policy measures will be diminishing. The rate of unemployment appears to have peaked at a much lower level than earlier expected. The process of business sector de-leveraging is moderating, with the pace of the decline in business credit lessening and indications that lenders are starting to become more willing to lend to some borrowers. Credit for housing has been expanding at a solid pace. New loan approvals for housing have moderated over recent months as interest rates have risen and the impact of large grants to first-home buyers has tailed off. Nonetheless, at this point the market for established dwellings is still characterised by considerable buoyancy, with prices continuing to increase in the early part of 2010.

… Interest rates to most borrowers nonetheless have been somewhat lower than average. The Board judges that with growth likely to be around trend and inflation close to target over the coming year, it is appropriate for interest rates to be closer to average. Today’s decision is a further step in that process.

So no mention of the true degree of labour market slack (more about this later).

I am always in two minds when it comes to thinking about these decisions. On the one hand, monetary policy is a very ineffective means of managing aggregate demand. It is subject to complex distributional impacts (for example, creditors and those on fixed incomes gain while debtors lose) which no-one is really sure about. It cannot be regionally targeted. It cannot be enriched with offsets to suit equity goals.

So, fiscal policy (when properly designed and implemented) is a much better vehicle for counter-stabilisation. However, the impact of monetary policy also has to be considered in relation to the levels of debt that households are currently holding. Australian households have record levels of debt and in the financial crisis lost a large slab of their nominal wealth. The RBA has always claimed that the debt was manageable because asset values were rising at a faster rate.

I always found the argument to be dubious given that a rising proportion of the “assets” being purchased with the increased debt were subject to significant private volatility (for example, margin loans to buy shares). But even more troublesome was the direct link between the debt-binge and the real estate booms which have pushed “investment” funds into unproductive areas at the expense of other areas of economic activity which would have generated more employment.

Part of the genesis of the financial – then real – crisis has been the skewing of economic activity towards “financialisation” and away from productive enterprise. So I found the RBA’s line unsatisfactory in that respect. Moreover, now that the household sector has responded to that sort of encouragement, the RBA thinks it is reasonable to punish the most marginal of this group with higher interest rates. Some people will default on their housing mortgages as a result of today’s decision.

The other reality is that the recession was not deep enough in Australia to really force a significant de-leveraging within the private sector. There is still considerable vulnerability there despite the rising household saving ratio.

Measures of inflation

The RBA’s formal inflation targeting rule aims to keep annual inflation rate (measured by the consumer price index) between 2 and 3 per cent over the medium term. So they have a forward-looking agenda and use underlying measures of inflation to assess the likely direction of the actual inflation rate that is published by the ABS.

The March 2010 RBA Bulletin contains an interesting article – Measures of Underlying Inflation – which explains the different inflation measures they consider and the logic behind them.

The concept of underlying inflation is an attempt to separate the trend (“the persistent component of inflation) from the short-term fluctuations in prices. The main source of short-term “noise” comes from “fluctuations in commodity markets and agricultural conditions, policy changes, or seasonal or infrequent price resetting”.

The RBA uses several different measures of underlying inflation which are generally categorised as “exclusion-based measures” and “trimmed-mean measures”.

So, you can exclude “a particular set of volatile items – namely fruit, vegetables and automotive fuel” to get a better picture of the “persistent inflation pressures in the economy”. The main weaknesses with this method is that there can be “large temporary movements in components of the CPI that are not excluded” and volatile components can still be trending up (as in energy prices) or down.

The alternative trimmed-mean measures are popular among central bankers. The authors say:

The trimmed-mean rate of inflation is defined as the average rate of inflation after “trimming” away a certain percentage of the distribution of price changes at both ends of that distribution. These measures are calculated by ordering the seasonally adjusted price changes for all CPI components in any period from lowest to highest, trimming away those that lie at the two outer edges of the distribution of price changes for that period, and then calculating an average inflation rate from the remaining set of price changes.

So you get some measure of central tendency not by exclusion but by giving lower weighting to volatile elements. Two trimmed measures are used by the RBA: (a) “the 15 per cent trimmed mean (which trims away the 15 per cent of items with both the smallest and largest price changes)”; and (b) “the weighted median (which is the price change at the 50th percentile by weight of the distribution of price changes)”.

While the literature suggests that trimmed-mean estimates have “a higher signal-to-noise ratio than the CPI or some exclusion-based measures” they also “can be affected by the presence of expenditure items with very large weights in the CPI basket”.

The authors say that in the RBA’s forecasting models used “to explain inflation use some measure of underlying inflation (often 15 per cent trimmed-mean inflation) as the dependent variable”.

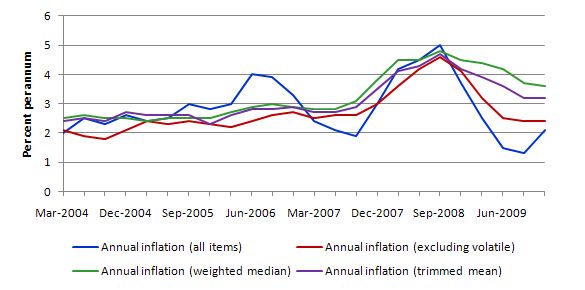

So what has been happening with these different measures? The following graph shows the four (data) that are published by the ABS – the annual percentage change in the all items CPI (blue line); the same change in the CPI excluding volatile items (red line); and the annual changes in the weighted median (green line) and the trimmed mean (purple line).

Remember the trimmed measures (weighted median and trimmed mean) are designed to depict tendency or trend and attempt to overcome misleading interpretations of trend derived from the actual series.

My interpretation is that trend inflation is heading lower although it is still above the 3 per cent upper-band. The other measures are in the lower half of the RBA inflation target band.

Commodity prices

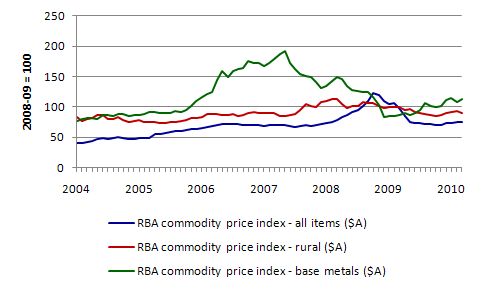

The following graph shows the movement in the RBA Commodity Price Index (data) from January 2004 to March 2010. The index is averaged to 100 for 2008-09.

The resources boom which began in late 2005 and peaked just before the crisis really took hold is evident in the base metals series. The data shows that the overall commodity prices is not heading upwards at any alarming rate. Base metals have recovered somewhat but it is too early to say whether they will reach the heights of early 2007.

However, in the context of the Governor’s statement which implies that the terms of trade are accelerating quickly the commodity price rises are modest. It is true that the exchange rate has appreciated but this is in part due to the interest rate spreads that the RBA has engineered (given policy rates in other major nations are around zero). Further the exchange rate is reducing the inflation rate and dragging the economy down via the reduction in overall trade competitiveness.

Are these rates rising because of the federal budget deficit?

We are starting to hear from the Opposition party (the conservatives) that the deficits are “crowding out” private investment as a result of the interest rate hikes. They clearly have been studying macroeconomics from Mankiw or some other fraudulent account of the way the macroeconomy works to be thinking this.

So we get these hacked versions of supply and demand whereby the government is sucking scarce capital out of the hands of the private sector to “fund” its deficits (which are wasteful anyway) and the strain on available funds pushes up interest rates. The rising rates are then alleged to crowd out marginal investment projects.

This logic commands a powerful place in the public debate but is plain wrong.

First, the federal government doesn’t need to “fund” its net spending because it is the monopoly issuer of the currency. It just “pretends” to “fund” itself by issuing debt $-for-$ to match its net spending. This practice was necessary during the gold standard and convertible currency era but after 1971 has no relevance.

As I have explained many times, the fact that this practice continued is due to the policy dominance of the neo-liberal ideology. They knew that after 1971, fiat currency systems meant that fiscal policy was no longer revenue-constrained. But their main agenda was not to operate the monetary system to its potential but rather to hamstring fiscal policy to give more space for the private profiteering.

So they needed to mount two attacks. The first on the wages system to ensure more of the real product was available to the profit share. They have been very successful in this quest – pressuring governments to bring in anti-union legislation and diminished safety net procedures (that is, minimum wage adjustments). The second attack was on the use of fiscal policy and the promotion of monetary policy as the primary counter-stabilisation tool.

Further, the concept of counter-stabilisation now focuses on inflation rather than income and employment. This is a reflection of the NAIRU belief that if an economy achieves price stability it will enjoy maximum growth potential and full employment. There is no hard research evidence to support this belief.

As I explained in this blog – The Great Moderation – the costs of this policy approach in terms of permanent real output losses and persistently high labour underutilisation rates belie the rhetoric. The so-called “natural rate” story is just blind ideology that comes from those who have an intrinsic loathing of government activity – unless of-course it is benefiting them directly!

I should add that the government would be hawking the same nonsensical line of argument (I won’t call it reasoning) if it was in opposition. That is just a reflection of how bad the state of politics is in Australia.

Second, the government just borrows back what it spent anyway (in a macroeconomic sense). There is no scarcity of funds. The government provided the funds by its prior spending. Some will argue that while this might be so, those funds could be better used by private investors and that preference is reflected in rising yields on public bond issues.

It is clear that the public debt auctions are starting to generate rising yields as private investors gain a renewed appetite for risk and are again diversifying their portfolios. From a private sector perspective that is a good thing. It also means that the income flow coming from the holdings of public debt will be higher (slightly) which is also a good thing. It makes very little difference to the government who just credit bank accounts anyway when they repay or service their debt.

And while the economies are well below full capacity there is no urgency about the composition of public spending and the danger that the interest servicing payments might squeeze out other desired government spending or force a rise in taxes to reduce the capacity of the private sector to spend and thus keep aggregate demand below the inflation barrier.

Further, the need for debt issuance declines because the renewed private spending reduces the public deficit via the reversal of the automatic stabilisers. Remember always that the fiscal balance is endogenous and driven by non-government spending decisions. The non-government sector can always drive the budget into surplus if they spend enough.

But the rising yields do reflect the mindless practice of issuing debt in the first place. They could avoid all this political angst by just net spending and leaving the added reserves in the banking system. Sure there would be an outcry that hyperinflation was coming. But in a year or more when inflation behaved no differently to what it does now – more or less stable with spikes reflecting supply rather than demand shocks – the cacophony of angst would subside. Then it would only be the Austrian fanatics who would be shouting and who would be listening?

Finally, the budget deficits by stimulating national income growth provide increased capacity for the private sector to save which means that there are more funds available for borrowers anyway.

The reality is that in our ridiculous system of “central bank independence” (another ideological construct from the neo-liberals to reduce democracy in the policy setting process) – the interest rate rises are the sole prerogative of the RBA board. Their logic is very simple and transparent – and erroneous.

They are single-mindedly focusing on the inflation rate and aiming to keep it within 2 to 3 per cent. So anything that pushes their estimate of the inflation rate above their threshold will bring interest rate rises – an export boom; a private investment boom; a private consumption binge; and a government stimulus. Further, the inflation might not even be driven by demand-pull factors. A supply shock (in some imported raw material; or profit push from the corporate sector) will elicit the same response.

So the mechanism via which the RBA’s logic works has nothing to do with “strains on funding” or “crowding out in financial markets”. Their model is Pavlovian – you think there is an inflation threat so hike!

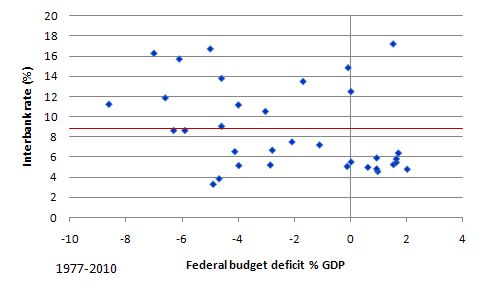

To give you some idea of the relationship between interest rates (measured as the interbank rate – because the available consistent series is longer than the policy rate) and the federal budget deficit as a percentage of GDP (annual data from 1977 to 2010 – the latter being to March and/or estimated). The horizontal red line is the average interbank rate over the period (8.7 per cent).

Now I wouldn’t read anything into this graph and I provide it only for interest. The causality can be working both ways. So a period of very high interest rates in the late 1980s (above 17 per cent in 1989) preceded the very harsh contraction in the early 1990s. In 1988 and 1989, the federal budget was in surplus as the self-styled “best Treasurer in the World” Paul Keating wanted to demonstrate how neo-liberal he was – for a Labor man it was disgusting. But during this period there was a positive relationship between budget surpluses and rising interest rates. But this was just correlation not causation – but should not be forgotten because it shows how mindless the conservative crowding out claims are.

As soon as the economy contracted, the budget went into deficit and this was maintained over the period of declining interest rates. But you will get some observations where high deficits are associated with high rates and of-course the causality does not go from deficits to rates.

But, in general, there is no coherent relationship between the two. As long as the federal deficits are non-inflationary they will not be associated with rising interest rates. Once the RBA gets the level of rates back to what it calls “average” or “neutral”, and that will be before the federal government eliminates its deficit – rates will stabilise again. Then there won’t even be correlations to look at, which is mostly the case shown by the graph.

So what is wrong with putting up rates?

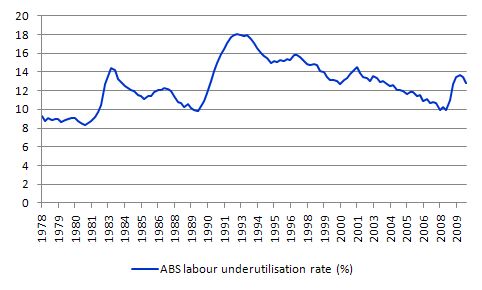

The next graph shows the ABS broad labour underutilisation from March 1978 to March 2010. This measure adds official unemployment to underemployment but ignores hidden unemployment (arising from participation rate changes during recessions). So in that sense, it is a better indicator of the state of the labour market than the narrow official unemployment rate but still underestimates the degree of slack (hidden unemployment is currently around 2.5 per cent).

The point is obvious. The NAIRU approach to price stability uses labour market slack as a policy tool and relies on maintaining a pool of wasted labour resources for its effectiveness. You can clearly discipline the price inflation process by inducing enough labour market slack. That is a no-brainer. But the cost of this slack is enormous. The mainstream economists justify this approach by claiming (as noted above) that the sacrifice ratios (the real output losses of disinflation policies) are low and transitory.

However, this is just a blind ideological statement and the overwhelming body of research on the topic including my own indicates these real losses are large and permanent. In my recent book with Joan Muysken – Full Employment abandoned we consider these issues in detail.

But while the permanent income losses are bad enough the personal and social costs that are borne by the unemployed and underemployed and their families (especially their children) are large and long-lasting. The research evidence is very clear – children who grow up in jobless households encounter considerable labour market disadvantage themselves once they become adults – and pass it onto their children in turn.

So there is a moral outrage here as well as an economic issue. I don’t support explicit government policy that deliberately and systematically imposes costs on a disadvantaged segment of the population. I also don’t support policies that deliberately and systematically force the economy to operate below its potential.

You will note from the graph that in the so-called long boom between 1992 and 2008, the Australian economy failed to get labour underutilisation back to its previous low-point (in 1989 of 9.9 per cent). So after 16 years of continuous economic growth (barring one negative quarter in December 2000) – we could still not get our wasted labour rate below 9.9 per cent of the available and willing labour force.

And just think about it for a second: we congratulate ourselves (or the politicians do) when we have nearly 10 per cent of our willing labour resources idle year-to-year. What sort of screwed priorities does that reflect? This is what the NAIRU constraints on policy lead to. While that is bad enough, the devious way the mainstream economists then try to cover their tracks and claim the true labour wastage is low etc (there are many spurious arguments used) is a disgrace. My profession is a total disgrace!

The persistence of high rates of labour underutilisation – the wasted people potential – alone indicts the policy framework in place which was a combination of the current monetary policy (inflation targeting began formally in 1994) and a bias towards fiscal surpluses (10 out of 11 between 1996 and 2007).

Conclusion

So what I take out of today is that the mainstream economic policy agenda that took us into the crisis is still alive in Australia. We have been lucky this time courtesy of our association with China (an unfortunate one should I add given the human rights abuses there) and the significant and early fiscal intervention by the federal government.

But we still have very high rates of labour underutilisation and given the only durable investment we can make in the future is in our people – I think the fact that this is no longer a policy target reflects the poverty of our era.

And may I just note it here – as I am doing a lot of background research at present on this question – the real danger for global inflation in the coming years will not be the budget deficits. The susceptibility will come from the energy sector as more and more people who used to be poor but now command incomes (for example, China and India) will drive energy prices upwards. I am noting it so I can claim “that I saw it coming” (-:

I covered some of these thoughts in this blog some time ago – Be careful what we wish for …. But now I am looking into it more deeply.

That is enough for today!

Several points.

1. It is correct to say that labor underutilization has social costs in addition to output costs and is important that economists admitt this serious externality. Especially when inflation is not caused by employment growth.

2. The relationship between public deficit spending and interest rates is not consistent and is irrelevant. As I have mentioned in previous comments rising interest rates from rising risks of default and risk aversion in periods of recession and crisis can coexist with deficit spending forthcoming in response to the shortfall of demand. Looking at the coincident data could lead to the erroneous view that a crowding out effect is taking place.

3. CPI increases when firms of consumer goods have market power can be related to upgrades of mark ups which can be caused by rising interest costs. Again, if this corresponds to a recession situation that brings public deficit spending, it can lead to the erroneous interpretation that deficit spending is bringing rising consumer prices.

4. I disagree that long term interest rates can be controlled(strong) instead of inlfuenced(weak) by CB policy. Long term rates can be shown as I have shown in previous comments in this blog to be dependent on a number of factors that CB policy is not easy to control.

There are a number of COAG targets relating to increasing qualifications and increasing the ability of people to be engaged in the workplace, from the National Agreement for Skills and Workforce Development:

Halve the proportion of people 20-64 without qualifications at Certificate III or above by 2020

Double the number of Diploma and Advanced Diploma completions by 2020

As well as Commonwealth Government policies to:

Raise the proportion of people 25-35 with a Bachelor Degree form 32% to 40% by 2025.

Increase the proportion of low-SES in undergraduate studies from 15% to 20%

What sort of national training policy would you like to see?

Dear Patrice

The supply side goals are fine. But they mean nothing without jobs.

I would like to see enough jobs created with integrated training capacity. Training is most effective in a paid-work environment.

I would also like to see a proper financial commitment to our universities as well instead of the race to the bottom our higher education system is now engaged in due to the need to “export” education to get funds.

best wishes

bill

If you think energy prices are going to drive inflation the Peak oil and in particular the Export Land model should be of interest to you:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Export_Land_Model

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peak_oil

In summary 10 oil exporting countries reduced production by over 9%, increased domestic consumption by 9% but reduced exports by 28% between 2002 and 2007.

I think you might be right!

Panayotis:

Points 1 – 3 agreed with the observation that post-recession pricing power also stabilizes due to industry consolidation – which I think is a much greater force that is sometimes noted. The firms that are left are able to match price increases as income rebounds. New firms / competition take time to form and grow. The interest rate hikes are associated with economic recovery – so the gains from pricing power increases are shared with financial rentiers.

Points 4 – not convinced – to the extent that the CB chooses interest rates to be influenced via market forces, they can decide not to implement policies that control rates over the entire yield curve. But the tools are still there. As a political point, yes I agree – but it is a choice of the CB (or the result of a political fight between CB and banks and govt), and not a structural limitation.

I was thinking about Kent H’s claim yesterday that the Fed has little power to increase lending, but may have some ability to decrease lending, and I have a question.

In “Money Multipliers and Other Myths,” Professor Mitchell does not write this exact phrase, but I have seen other advocates of modern monetary theory state that operationally reserves are not “loaned out.” Instead, the act of originating a loan creates new deposits. My understanding was that what this means is that the process of making a loan results in the creation of new “credit money.” This new credit money does not add to net-financial assets though because it is a “horizontal transaction.” That is, the asset created (the loan) has a corresponding liability (the deposit). Credit money can, however, be used to create real assets. For example, if you take out a loan to build a house, when the loan is paid back the loan and deposit disappear (although, the interest on the loan would still exist…I never really understood that part), but the house that was built with the loan remains.

So here’s my question: the fact that increasing or decreasing the federal funds rate (or whatever Australia’s equivalent is) can affect a bank’s decision to loan seems to me to contradict the above claim that, “reserves are not loaned out.” If reserves aren’t being loaned out why should the interest rate the banks pay for reserves (either the discount rate or the federal funds rate depending on where banks borrow from) have any affect at all? Also, in “Money Multipliers and Other Myths,” Professor Mitchell writes:

“…loans are made independent of their reserve positions. Depending on the way the central bank accounts for commercial bank reserves, the latter will then seek funds to ensure they have the required reserves in the relevant accounting period.”

But this seems to imply that reserves are indeed loaned out. Otherwise why would the bank have to seek funds to ensure they have the required reserves in the relevant accounting period? What am I missing?

“And just think about it for a second: we congratulate ourselves (or the politicians do) when we have nearly 10 per cent of our willing labour resources idle year-to-year. What sort of screwed priorities does that reflect? This is what the NAIRU constraints on policy lead to. While that is bad enough, the devious way the mainstream economists then try to cover their tracks and claim the true labour wastage is low etc (there are many spurious arguments used) is a disgrace. My profession is a total disgrace!”

You said it yourself, the whole post, to a casual observer, is filled with ‘conjecture’ (not by you but by those manning the levers and switches of our crippled and crazy financial system.)

I’m going to guess ‘official’ unemployment in Australia is similar to how it is ‘measured’ here in the US, so your 10% figure is a number derived from some nebulous ‘in the workforce’ designation.

Of an ‘unofficial’ 211 million person workforce, a full 80+ million are counted as ‘non-participants’. (Worse, 40% of participants only work part-time because that’s all there is!)

Bizarrely, the unemployment rate is dropping in the US, not because hiring is increasing but because people are exhausting their unemployment benefits.

How convenient is it for the cheerleaders of…(fill in your own blank) to have a ‘surrender’ feature that makes the ‘headline’ figures appear more acceptable?

Naturally, with the degree of ‘perception management’ going on, can any of us have any degree of confidence that the situation is even remotely ‘as advertised’?

Which brings us full circle to the real ‘rub’…”What are you gonna do about it?”

Short answer, nothing! The system doesn’t provide the tools necessary to repair the system.

Bill,

I have grave concerns about the Coag targets Patrice so kindly outlined for us.

If governments associate themselves with training organisations such as those doing Cert III and IV type qualifications then it would be in the best interest of the training organisations if jobs were scarce.

The less jobs available the more likely people would be to seek training. This would be especially so if the government forced the unemployed to participate in training programs or else lose their payment entitlements (Even though no Job would exist either during or after the training was completed).

That way the training organisations are given a consistent stream of business they would probably not otherwise have if the government adopted a full employment strategy.

Those in employment are far from safe either in being pawns used to fill the coffers of training organisations.

Government subsidies and tax concessions to organisations for otherwise worthless training come to mind. All this has led to is an industry of worthless certificate printing without any focus on jobs or training that in any way meets the economic needs of the nation (Full Employment that is environmentally sound and contributes to peoples quality of life).

Worse still is that some businesses are also becoming registered training organisations and effectively making more money now than they did previously through their core business activities (RSA and RSG certs and the like are one such scam making a lot of money and providing little if any public benefit.

Those with jobs are effectively being trained at what they were already competent in for many years. Where the training is tied to a job I know of many examples whereby an employees status has been changed to that of a Traineeship in something they are already competent in. The Business / training organisation cashes in, the government can say a new traineeship was created and the general public are none the wiser to what is really taking place.

The less said about JSA members and how they nominate skills in demand to the DEEWR the better other than they often nominate skill shortages in areas they have training courses in – how convenient.

Cheers, Alan.

Dear Pebird,

Regarding long term rates if you read my formulations in previous comments it can be derived that these rates depend on a number of factors that are not easily controlled and sustained by CB policy. In my mathematical models including stochastic versions long term rates are influenced by maturity/duration trade, probability of default whose calculation depends on a number of factors, probability distribution specification, stochastic/jump factors, etc., changes in inflation, changes in GNP growth, in addition to long term trends in real GNP growth and inflation. There are too many factors that influence expectations and the long outliers of the yield schedule.

Regarding points 2-3, I am trying to point out that interest cost cannot be sustained unless there is market power, which is a Minsky point, that raises mark ups and prices to receive the revenue to validate this cost obligation. In a recession this cannot be sustained and any rising prices amplifies the negative effect on income and it has nothing to do with deficit spending. So rising interest rates from factors such as risk aversion and uncertainty of default conditions and rising prices from any market power to cover interest costs are not caused by public deficit spending that responds to effective demand shortfall.

NKlien 1552: But this seems to imply that reserves are indeed loaned out. Otherwise why would the bank have to seek funds to ensure they have the required reserves in the relevant accounting period? What am I missing?

Reserves aren’t loaned out since reserves only exist in the interbank settlement system, in the US, the FRS. Under the gold standard, when reserves really were reserves under a convertible flexible rate monetary regime, one could demand the corresponding amount of a gold in exchange for a dollar. Now, a dollar Federal Reserve note will only get you another FRN. The FRN is actually a proxy for a reserve, since banks exchange reserves for notes depending on window demand.

Keeping the interbank settlement system separate in one’s mind from the nongovernment banking system and economy is essential for understanding the vertical-horizontal relationship in MMT, and how the accounting is done.

As a practical matter, regardless of whether there is any reserve requirement at all, banks have to settle their accounts in the interbank system, and for this they require reserves. If they have insufficient reserves to settle, they have to borrow them at a cost, namely, the going interbank rate, e.g., in the US, the fed funds rate and in the UK, LIBOR (London interbank overnight rate). The bank making a loan then figures this cost into the spread as one factor in determining what to charge for extending credit. So in this indirect way reserves affect the horizontal system by influencing the price of credit. But the reserves themselves stay in the interbank system. Therefore, it is not correct to say that banks loan reserves.

Gegner: Short answer, nothing! The system doesn’t provide the tools necessary to repair the system.

I would say rather that the present system subverts the tools necessary to repair the system, in the interest of those who profit from this subversion.

“Reserves aren’t loaned out since reserves only exist in the interbank settlement system…”

“If they (banks) have insufficient reserves to settle, they have to borrow them at a cost…”

But my question is if reserves are not “loaned out,” why would banks have insufficient reserves to settle? Where did those reserves go?

Agreed! Left to our imagination is whether or not this was an ‘oversight’ or (more likely) ‘intentional’. While we study the minutia, the few are dancing around in the cracks they control, manipulating both the meaning and the intent of the true heart of the matter, the law.

Which raises a more disturbing question, is it worthwhile to obsess over abstractions when their meaning is mutable?

Not to confuse anyone and to prove I’m not ‘talking in circles’ I present the ‘main conundrum’ for your consideration, if a pig is a pig and a duck is a duck, why isn’t a dollar a dollar?

NKlein:

Think of reserves as an asset transformation to a form that can only be used for certain purposes. Cash is a different asset transformation. Loans (if you are a bank) are another transformation of assets (the asset of collateral + an individual’s ability/promise to repay). It is providing motion to a stock, turning it into a flow. Each asset form can do different things.

One function these transformations provide is to summarize a bunch of detailed flows into a new form (according to certain rules), which can then be controlled by different mechanisms.

Banks loan bank money – money they create (the liability) offset with an asset (loan). They are able to do this given certain rules of which include reserve rules. They can get reserves in a few ways: from public deposits, from other banks (those that have too much lend to those that need), selling assets or putting up collateral (like toxic securities) and borrow from the CB window (which is also paying interest on those excess reserves now, what a deal).

Note that not all deposits automatically become reserves, it depends on the activity of the bank, the deposits they can turn into “vault cash” (not needed for daily operations) as well as what they deposit at the Fed comprise their reserves. The Fed requires banks to maintain reserves of at least 10% (I think) of demand deposits. This requires a transformation (via a set of rules and regulations) that turns deposits into reserves. Zero reserve requirement countries still require that the banks have sufficient reserve balances to settle, but it is calculated differently and the link to customer deposits is severed.

Also note that just having the required reserve position doesn’t mean you can loan – there are other regulations that must be met.

You can say that reserves “back” lending – in that the bank has complied with all the regulations needed to generate their loan activity. But with regard to reserves, this is to ensure that the bank has sufficient liquidity to meet demands for settlement (either depositor or interbank), not to “loan” out the reserves. A bank can create much more bank money than they have reserve balances – so they would “run out” of reserves very quickly if they were loaning out reserves.

Gegner

I have heard you ask the question ” if a pig is a pig and a duck is a duck, why isn’t a dollar a dollar?” before and Im still not sure what sense you are referring to regarding the dollar.

Do you mean why doesnt a dollar buy the same amount of stuff everywhere? Are you referring to what a days labor earns you in China vs in the US?

Could you clarify please.

nklein:

a bank may have insufficient reserves to settle because it leant out money that was deposited in a different bank. Or someone wrote a big check from their bank to another bank. Or the bank bought lots of Treasury bills and is therefore short on reserves.

If reserves are not in one bank they are in another! But they must stay in system.

The exception is when you take out cash. Then reserves leave system as you debit reserve (asset) and deposit (liability) and cash currency is not connected to central bank.

Just one clarification (maybe just semantics) – when cash is removed then reserves are reduced – reserves are transformed into cash – reserves don’t actually leave per se – but because they are both denominated in the same currency unit then it looks like reserves leave the system. It’s like saying the electricity leaves the battery when the motor spins. Not really – the energy is transformed, the electricity is cycled into the ground – which is kind of like the Central Bank – the big black hole where reserves disappear and reappear as needed.

pebird: You can say that reserves “back” lending

I would not put it this way in order to avoid giving the impression that banks loan against reserves. Banks loan against capital. That is to say, it is the bank’s capital that is put at risk through credit extension, not bank reserves. A bank is penalized (a cost) if they fall short on reserves in a particular period. But should they fail to meet their capital requirement, they must either do so forthwith, or else face being put into resolution, in which case equity is charged first and then debt if there are losses.

Thanks pebird, Tom Hickey, and zanon. I think I understand now. I’m going to mull over this for a few days.

“Banks loan bank money – money they create (the liability) offset with an asset (loan).

What about the interest charged?

Does this come from the government’s deficit spending? If so, what do we need the banks for in the first place?

It seems to me that a sovereign nation needs just one national bank that works in the interests of its people without the need to make a profit.

Inflation and Interest Rates.

Inflation that matters in Australia right now is house price inflation. Houses are SHELTER not commodities for speculation. The baby boomers have turned housing into a speculation. The return on a house investment is less than the return on bank deposits even after adjusting for inflation. The only reason for someone to buy a house as an investment in Australia then is speculation.

Bill Said; But even more troublesome was the direct link between the debt-binge and the real estate booms which have pushed “investment” funds into unproductive areas at the expense of other areas of economic activity which would have generated more employment.

Part of the genesis of the financial – then real – crisis has been the skewing of economic activity towards “financialisation” and away from productive enterprise.

Some of you can spend your day pontificating about Bank reserves and impress us with your wordy arguments but can any of you suggest how to divert wasted resources from speculating in other peoples Shelter.

Better to have flexible tax policy to direct real Capital to areas of the economy where it can be put to use in creating real growth. We need to sort out shelter for our people before you fix the worlds financial system.

Land Bankers must be taxed in a way to force them to develop more blocks instead of the steady and controlled release of land from massive master planned communities. The manipulation of supply together with Shelter speculation has caused massive price increases that ultimately drain real demand and must eventually prove Minsky right.

Greg, sorry for the delayed reaction other matters pressed. I am indeed referring to the bizarre ‘floating’ aspect of what should be both a uniform and universal…er, ‘standard’.

If we take our pig then we must ask ourselves if pork shouldn’t cost the same wherever you find it? The ‘ original purpose’ of money was to ‘simplify’ barter and provide a better answer to the question of ‘how many ducks equal a pig?’ It was also intended to simplify the trading process. If you could trade your goods for money you didn’t need to find ‘exact matches’ for the other goods you desired to trade for.

Understand my problem. I spend every week on food what the average Chinese worker makes in an entire MONTH (makes me sound like a pig, doesn’t it?)

Why doesn’t the Chinese worker starve to death? If I had o cope on the wages they’re paid, I certainly would.

Even more curious is the Chinese worker isn’t ‘destitute’ although they are paid a fraction of what we make here.

By all rights the ‘cheaper there’ cannot exist (without severe currency manipulation.)

jls:

“What about the interest charged?”

First of all, the bank pays salaries, expenses, interest to depositors. All of that feeds back into the economy.

Also, loans do get restructured (there is a hit on reserves, which shrinks liquidity). Finally, as the government spends, this high-powered money does not have a liability attached to it.

So, if you are thinking about the bank not creating the interest needed to service the entire loan, that is true but it is not as large as you might think and besides government spending has to be taken into account. Those calculations that you see on the internet that takes the amount of private debt and implies an average interest rate to show this huge number illustrating some kind of money gap aren’t accurate.

Tom:

You are right – after I posted that I realized it could be misconstrued. The “backing” reserves provide is liquidity, not funding. This is an old gold standard concept where reserve convertibility and money circulation were linked and liquidity/settlement were coincident with private solvency.

Backing is really the wrong word to use in regard to reserves – although I don’t know if in reality capital is backing loans either – this is a consequence of Waldman’s argument – if you can’t measure capital with accuracy – how can you definitively say a loan is backed by capital? Interesting problem. Waldman argues that public capital (the ability of the economy to produce real wealth) is backing private speculative behavior – and he says that isn’t necessarily a bad thing depending on how it is structured and controlled (currently structured very poorly).

pebird, the general idea of risk-taking in a market economy is that risk is “backed” by capital, in that it is capital (equity and debt) that is put at risk in expectation of return. This is what market capitalism is about. Capital is favored over other factors of production on the idea that capital will not be put at risk otherwise, in which case a free market economy is impossible, since capital is the driver.

What Waldman is saying is rather theoretical; however, everyone extending credit or funding an enterprise realizes that their prospect of realizing a loss is not at all theoretical. It is very real, and a number can be put on it in terms of capital at risk. Investing is supposed to be about estimating risk in relation to return as precisely as possible based on probability. Of course, the future is always uncertain – external shock, for instance; therefore, the disclaimer that past performance is not necessarily an indicator.

Capital requirements are designed to ensure that banks have sufficient capital to provide against losses. Banks also have their own departments that figure the amount of risk capital to commit to each loan based on probability of default given the circumstances. A prudent institution doesn’t try to sit precisely on its capital requirement to make the most profit, or fudge the accounting and engage in off-balance sheet maneuvers in order to make even more. If banks get caught short of capital, they are supposed to be put into resolution – unless there is a quick capital injection or “regulatory forbearance.” This is the story of the present crisis, and no one yet knows just what is going on, because the banks and regulators aren’t saying. But many opine that it is Enron writ large if the truth be known.

Conversely, the bank department that manages reserves has the responsibility for liquidity provision by ensuring that reserves are sufficient for settlement of interbank claims. If they goof up, it costs the bank a penalty fee that reduces profitability but it doesn’t put them under.

Gegner

While I admit that currency manipulation is part of the issue I dont think it “explains away” all of the conundrum you note above. Some of it is basic economics I think. China has lots of rice so it is cheap for them (almost free) and many Chines do not require or desire to live in framed house with metal roof and marble counter tops. Many Chinese may have even built their own houses from materials abundant on nearby land. The Chinese do not have to pay for as many thing as we do ( maybe we are the fools getting taken) so everything they make is saved.

Certainly this does not dismiss exploitation by foreign and Chinese business interests looking to profit form the difference in current preferences and needs. The rub will come when Chines workers wonder why they are working 8 of their 12 hours making stuff for someone else that they could keep for them selves. This of course will primarily be Chinas problem but given the interrelatedness of things we will be affected as well.

Tom:

I disagree that capital requirements function as loss provisions – during a crisis. During normal (whatever that means) periods – sure, the capital requirement gets rid of marginal players. During a crisis, there is little possibility to raise capital, so if you are hit by a unforeseen loss (not of your own making), like a counterparty settlement problem – you can hit capital limits and be insolvent. Just hope you are TBTF.

The solution is of course not to get into crisis in the first place, and among the reasons we got there include: 1) there was phantom capital on book and/or liabilities off book, 2) we can’t measure capital adequately even if it were legitimate.

Now, if you are saying what Waldman really means that the lack of capital meaningful measure is a symptom of the problem – that capital can be meaningfully measured, but the destruction of regulation rendered any measurement impossible – I can appreciate that perspective.

But I wonder if there is a velocity issue here. Assuming the old Marx declining rate of profit theory has some validity, one way to increase total amount of surplus is by increasing turn. I can make a lot of money on 0.01% margin if I flip a lot. So the entire elimination of system “friction” was driven not just by “evil speculators” but also a very real lack of profit potential at normal rates of turnover. As a result, regulations were put aside, speed increased, the ability to snapshot capital positions was lost and voila, crisis.