I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Some movement at the station

Today I reflect on my weekend of media reading. Within the never ending media assault on budget deficits which is now being regularly elevated to “the fiscal crisis of the state” I read a few stories which actually took a different tack. One said that several national leaders were going to prioritise jobs over the wishes of the financial markets while the other said that the so-called “debt moralists” (aka deficit terrorists) are not on sound economic grounds. Amidst the continual conservative onslaught at present, both articles reflect some movement at the station!

Today’s title is borrowed from the classic Australian poem by Andrew “Banjo” Paterson The Man from Snowy River. We learned it word perfect when we were at school and it still resonates beautifully. In common parlance, the expression is now used to mean a shift in sentiment.

Anyway, while the poem is beautiful … today we are talking bond markets and ugly stuff like that.

As an aside, last week I noted that US government bond yields haven’t budged.

On Friday (February 19, 2010), the US Bureau of Labor Statistics released the latest US inflation data showing an easing in consumer prices. What inflation there is reflects energy price movements which can hardly be considered a consequence of the fiscal stimulus measures.

So what will the gloom merchants be looking for next to provide succour to their ill-informed fears? Tax rises I guess. We should all start laughing now!

Anyway, over the weekend, I thought two articles in the UK Guardian provided welcome relief from the torrid neo-liberal media onslaught of late.

The first article – Britain, Greece, Spain and Norway tell markets: growth, not cuts (February 19, 2010) – reported that the “Centre-left leaders defy mutinous global investors”. The story said that:

The prime ministers of Britain, Greece, Spain and Norway have warned the financial community that they will prioritise growth over deficit cuts, and have asked speculators to change their short-term view for one that is more favourable to society as a whole.

Well Greece and Spain are not in a position, as they stand, to do much about it (unless they take the wise choice and dump the Euro in favour of sovereignty). However, as I explained in this blog – Who is in charge? – the governments of Britain and Norway are 100 per cent sovereign and can resist the machinations of the so-called “investors” if they choose.

As an aside, it is really annoying when economists blur language and call financial market speculators “investors”. In economics, investment is defined as spending with augments productive capacity. Financial market speculation is nothing remotely like that and should not be called investment behaviour. Small point though!

The Guardian quoted the Spanish leader:

We won’t fall in the trap of those who provoked the credit crunch … We will cut the deficit when economic recovery is active, but not at the expense of social cohesion.

This is in relation to the speculative push on bond yields in several countries in the last month or so which have raised the cost of borrowing for the governments in question. Then, of-course, the deficit terrorists turn around demand even more austerity.

The speculators have also pushed up the credit default insurance premia and the corrupt ratings agencies have sought to stay relevant by issuing threats to the sovereign debt ratings.

But the reality is that despite the tough talk by the leaders they are still signalling their compliance to the “markets”. Greece has already begun implementing its plan to get the budget deficit down to 3 per cent of GDP (from 12) by 2013. That will require massive cuts which I consider will cause major social instability in that country.

The UK is also talking tough on fiscal austerity which will cause significant damage at a time that they should be providing further net spending support for aggregate demand.

The Spanish leader was quoted as saying:

We have to tell the markets that they should have a more medium and long-term perspective … It’s a paradox that the markets that we saved are now demanding and putting difficulties, as those budget deficits are those that we incurred to save those who now demand budget cuts. What a paradox.

The Guardian quoted some character from “the markets” who said “The market is now only interested in liquidity. We have to be focused on the short term: if you’re concerned about funding, you have to look short-term”.

Well if I was the running these legislatures I would in the case of UK dramatically reduce the scope of “the markets” to engage in speculation. Please read my blogs – Operational design arising from modern monetary theory – Asset bubbles and the conduct of banks – Breaking up the banks – for my sketch of the necessary financial market reform.

I would also instruct the central bank to manage the public yield curve to shut out the speculators. This blog – The vandals are gathering – explains how that could occur.

If the citizens really understood that sovereign governments do not need to be “funded” and therefore submitting themselves as be victims of the short-term greed machines (bond traders) is totally unnecessary then I think the public debate would change.

We would more often hear politicians being asked to explain why they are destroying jobs and increasing poverty rates and using the weak claim that the bond markets require exit plans. The bond markets might require exit plans but their motives are to advance their own narrow sectional interest and this definitely does not coincide with the attainment of national welfare and public purpose.

And what the bond markets require should be irrelevant to a sovereign government. Japan has shown that it can ignore the ideology sliming its way out of the bond markets and the ratings agencies and suit themselves.

As a professional observer of these machinations for a few decades now, it never ceases to amaze me how the citizenry is effectively rendered ignorant and therefore denied their rights to vote on the basis of informed choice by the duplicitous smokescreen that the elites have erected to hide the true nature of the monetary system.

The so-called land of the free (US) has refined this duplicity to a fine art form.

The second Guardian article came from long-time journalist Will Hutton (February 21, 2010) – To thrive we need to distinguish between morality and economics and it argues that the “current battle between the economists may seem to be about economics. It is not. It is about the morality of debt”.

Hutton claims that “(n)othing is more certain to arouse the armchair moralist than too much debt” and “(i)f private debt arouses these sentiments, fast-growing public debt is even more provocative”>

But he then says:

… debt morality should never be confused with good economics. Good economics attempts to deliver a functioning economic system that works for all its members. Necessarily, credit and debt play crucial economic functions, allowing the system to manage the inevitable mismatches between flows of revenue and costs over time. Changes in public debt are a vital instrument to manage the economy efficiently and, crucially, morally and fairly.

So you see that while he is a social “progressive” he still is perpetuating the idea that the UK government has to borrow to spend. It clearly does not and chooses this unnecessary strategy because it is under the neo-liberal spell.

Hutton then talks about the “battle between 60 economists who signed letters to the Financial Times repudiating the 20 who earlier signed a letter to the Sunday Times urging that Britain’s public deficit to be eliminated” and says it is not a matter of economics:

Economics is on the side of the 60. The gulf is about the morality of debt. The Sunday Times 20 are less economists and more, like the Tories, debt moralists. Underneath their unsubstantiated claim that currency and interest rate crises are inevitably associated with high public debt, so that recovery will be menaced, lay the scarcely concealed language of morality. By saying that the deficit was the largest in peacetime history, without placing it in the context of the largest-ever recession, the inference was clear. A government that needed to regain trust was immorally taking debt to exceptional levels without good reason. Budgetary propriety had to be restored fast.

More of this sort of writing should hit the media. It is clear that those who are pushing for fiscal austerity right now haven’t a clue or don’t care about the economic consequences should their wacko suggestions actually be followed (which unfortunately they are).

The damage to economic growth and jobs which will accompany these austerity packages cannot be sound economics. It is all about ideology or in Hutton’s words morality. A sickeningly dishonest morality at that given that the ones who are emerging as most vocal all had their hands out at the onset of the crisis to get their share of public bailout money.

Hutton provides ample evidence to support his view that fiscal policy has been effective in shoring up demand and stopping the world falling into a depression. He shows that private saving is now rising as households try to bring down their debt levels.

He rightly concludes that:

It is plain that if public spending fell any faster than the government plans, ie if there is an attempt to more than halve the deficit over four years, then growth would be even lower. But as the forecasters say … whatever the credit-rating agencies may say, Britain has not defaulted on its debt since the 14th century. There is zero risk today.

So in terms of the “economics” there is no case for fiscal austerity and “policy driven by debt moralism is not credible”. He concludes that the credible option is to “deliver ongoing growth within which the structural deficit can be attacked”. I wouldn’t use the term attacked. Adjusted as appropriate is more what is required. Appropriate relates to the state of overall aggregate demand.

After reading these articles, I was sent another article today which also suggests that the media is not exclusively pushing the debt moralists line.

The normally ultra-conservative Business Spectator in Australia had this to say about one of the News Limited rants at the weekend:

Which is one reason why this column is growing frustrated with US deficit hawks. Today, it’s Max Walsh charging in for The Australian. “America’s public debt to GDP ratio has soared from 37 per cent in 2007 to what is expected to be 60 per cent this year … To put that figure in perspective, it is the highest ratio ever recorded except for a World War II peak … higher than World War I or the Great Depression … According to Spyros Andreopoulos of Morgan Stanley’s London office: ‘From a fiscal point of view, it’s as if the economy has gone through World War III.’ … His US colleagues expect the ratio to hit 87 per cent by 2020…Rapidly rising public debt ratios of these dimensions can undermine market confidence because they are historically associated with slowing growth, rising inflation, exchange rate deterioration and, in a worst-case scenario, default on public debt.”

This column has news for Mssrs Walsh and Andreopoulos. The US is fighting the economic version of World War III. Walsh prattles about “damage to market confidence” without mentioning that it was the government bailout of the excesses of that confidence that got it into this mess in the first place. Without the dramatic nationalisations of the GSEs and AIG, the TARP and the stimulus spending, the US economy would have entered a debt-deflation black hole. Moreover, as this column has previously pointed out, with over-capacity and debt deflation in full roar, the US has about as much chance of generating internal inflation as this column has of being satisfied with commentary every morning.

It speaks for itself. But don’t get the impression that a groundswell is emerging.

Back at News Limited there was the usual mindless sensationalism coming out from its Economic editor at the weekend. Michael Stutchbury wrote on February 20, 2010 in the national daily – The Australian that – A quick return to surplus could show the world the way

Yes, it would show the world how to slow down recovery and entrench joblessness.

Stutchbury is one of the vocal deficit terrorists who just writes what he thinks the conservatives like to read. In this appalling article, Stutchbury pushes the same stories he gets from other conservatives – nothing original here. So we get Greece … then Dubai … then:

… last year’s huge budget stimulus packages, bank bailouts and recessions are transforming the global financial crisis into the fiscal crisis of the state.

Really. What exactly is a fiscal crisis of the state?

Greece has one because it is the EMU. It could ditch that and it would regain sovereignty and then the only crisis it would have would be a real one – getting its real output growth going and unemployment down.

Dubai has no fiscal crisis of the state. It can pay all its outstanding financial obligations which is not to say that private businesses in Dubai can.

Anyway, Stutchbury then drops Niall Ferguson’s stupidity into the mix the “no such thing as a Keynesian free lunch”. I wrote about that last week in this blog – Person the lifeboats!.

So how do we get a fiscal crisis of the state in Australia?

Stutchbury blurs the issue and starts talking about “our high foreign debt and household debt” and some need “to finance our balance of payments deficit”. He notes some financial market character he has been talking to “calculates that, despite negligible government debt, Australia’s overall debt amounts to just under 300 per cent of gross domestic product: a little less than Italy and a touch above the US.”

So what has that got to do with a fiscal crisis of the state?

There is clearly massive debt holdings in the private sector mainly in the household sector. The private debt build-up occurred during the period that the federal government ran increasing budget surpluses. In fact, growth was only possible between 1996 and 2007, given the massive fiscal drag because of the debt-fuelled consumption binge. In the later years of this period it was also helped by the commodity price boom.

If the private sector had have avoided the pressure put on them by the “financial engineers” who were intent on loading the private sector up with as much debt as they could during this period, then the federal government would not have been able to have run the surpluses for very long.

The fall in aggregate demand would have driven the budget back into deficit very quickly. So the surplus squeeze on private liquidity was only possible because the latter binged on debt. It was always an unsustainable growth strategy.

So it is clear that the private sector has to reduce its debt exposure – which is a common requirement across the globe – if stable growth is to return.

But that process has to be supported. How? Well it depends on the external sector. For Australia and the US and most nearly everywhere else, external deficits are the norm. That is, they are net leakages from the expenditure stream.

So if the private domestic sector is to enjoy sustained overall saving then with external deficits in place, the public sector has to run budget deficits.

That is the only way that we will have stable growth with the private sector not spending more than its income.

Further, the need to “to finance our balance of payments deficit” is a misnomer. Our negative net exports position actually “finances” the desire of the foreigner to accumulate financial assets in our currency. They need us! To claim we need to “finance” it is mis-representing the way these monetary operations work. Please read this blog – Modern monetary theory in an open economy – for further discussion of this point.

Anyway, then we get to the nub of his article.

From a modern monetary theory (MMT) perspective, the Australian government is stupidly planning to reduce its deficit to 1.1 per cent of GDP by 2012-13 and then “return to surplus by 2015-16”. The public deficit is currently around 4.5 per cent of GDP.

This is clearly too small at present given that GDP growth is flat and total labour underutilisation is around 13.5 per cent.

But not to be concerned with facts, Stutchbury wants the government to get back into surplus 2 years ahead of the current plan. He claims that unlike the UK and the US which are going to have to inflate “their way out of their sovereign debt crises”:

… a committed budget surplus would be a powerful assertion of Australia’s economic resilience and Asian-flavoured prospects.

Then we are taken back to Greece; Portugal, Spain and Italy, and threats that Britain and the US were about to lose their AAA credit rating – and you just have to wonder how frenzied this journalist’s mind is when he writes. It is if he has to string all the “Glenn Beck” moments together into one article – in no particular order – and with no logical context.

Anyway, Stutchbury thinks this plan would “offer multiple economic and political benefits”:

First, as global bond yields rise, the markets will reward economies with strong public balance sheets and credible debt repayment policies …

Second, the budget tightening required by a four-year surplus target would take some of the pressure off the Reserve Bank to lift official interest rates as it eases inflation back to target.

So we are back to the hegemony of the bond markets and inflation targetting. The crisis has not purged us of these neo-liberal mantras.

The question is whether he has any idea of what will support aggregate demand and therefore economic growth if the government cuts net spending so hard as to engineer a surplus.

Net exports is not about to turn positive. The private sector is highly geared and is now showing that it wants to net save. So where is the growth going to come from?

Stutchbury was not alone. I won’t link to the article but the self-serving Business Council of Australia were calling for the same thing.

And the reference to Glenn Beck relates to his speech at the Conservative Party of America conference at the weekend – here is a review – where he labelled the true enemy of the world as “progressives” and linked them to communism and all manner of pestilence.

But when I watch nonsense like that I realise why some of the commentators in our midst jump from public sector job creation to draconian communist dictatorships without taking a breath in between. Absolutely anti-intellectual and mindless stuff.

Stutchbury would have been at home in the audience.

Which brings me to something that should be the real focus in the media debate but which is typically ignored by the deficit terrorists.

Unemployment – a very long tail

There was an interesting story in the NYT on February 20, 2010 entitled – The New Poor Millions of Unemployed Face Years Without Jobs.

The main argument of the article is that while:

the American economy shows tentative signs of a rebound, the human toll of the recession continues to mount, with millions of Americans remaining out of work, out of savings and nearing the end of their unemployment benefits.

The journalist provides a lot of case material of interviews with unemployed workers in the US which spells out a very gloomy future for many Americans.

The interesting twist in this downturn is that there is now a “new poor” emerging in the US:

… people long accustomed to the comforts of middle-class life who are now relying on public assistance for the first time in their lives – potentially for years to come.

I have done some work last year with my colleague Scott Baum about the emergence of new areas of disadvantage in Australia – that is, areas which we never considered to be disadvantaged in the past. That tag was usually reserved for old decaying industrial areas which are suffering the decline in manufacturing.

But the new areas of emerging disadvantage are the mortgage belts where young householders are carrying massive debts – the hangover from the last housing boom.

We are doing more work on this at present. But it is interesting that the phenomena is also being observed in the US.

The article says that there are now:

… 6.3 million Americans who have been unemployed for six months or longer, the largest number since the government began keeping track in 1948. That is more than double the toll in the next-worst period, in the early 1980s.

Men have suffered the largest numbers of job losses in this recession. But … women from 45 to 64 years of age … [their] … long-term unemployment rate has grown rapidly.

In 1983, after a deep recession, women in that range made up only 7 percent of those who had been out of work for six months or longer, according to the Labor Department. Last year, they made up 14 percent.

Long-term unemployment not only brings joblessness. The loss of income then starts to erode the capacity of the person (and their family) to maintain adequate housing. Health care suffers and family breakdown rises.

The societal costs of not intervening to prevent long-term unemployment from becoming entrenched are enormous and span generations. I find comments from people that we should care about these costs and let the markets sort it out to be nonsensical from all perspectives. Even a hard-line mainstream economist should realise that entrenched unemployment is not easily solved and that supply-side solutions (lower wages; more onerous work tests; cutting benefits; etc) do not work!

I used to ask right-wingers who railed against my ideas to implement wide-scale public sector job creation why they thought home break-ins were rising in their area? And even if they hated the idea of some disadvantaged worker being given a little “leg up” in life at no-one elses’ expense, didn’t they care about their DVD players and plasma TVs and the rest of their material gadgets getting stolen?

An unemployed person produces nothing. Any production above nothing is am improvement in efficiency quite apart from the social benefits that accompany employment.

Further to understand why the problem is not just a matter of income support – please read my blog – Income or employment guarantees? . There I summarise the dominant research literature that finds the benefits of employment go well beyond the provision of income. Merely providing a person with a guaranteed income deny them of the social aspects of work which include self-esteem, social inclusion, integenerational benefits of children observing work habits; etc.

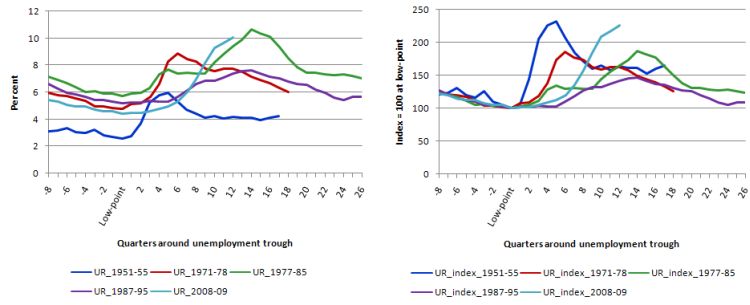

To see the time profile of unemployment I constructed the following graphs for the US. The data looks like this for all countries but since the story was about the US labour market I chose to highlight that. The unemployment rate data is from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

They are inverse butterfly plots. The left-hand panel shows the raw unemployment rates 8 quarters before the low-point in the respective cycles then to the peak (the labour market trough) then 12 quarters after the peak is reached. So the span varies by the different periods between the low-point and the peak. I chose recessions derived from US GDP growth data derived from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis.

The episodes graphed span the periods 1951-55; 1971-78; 1977-85; 1987-95; and the current period, 2008-09.

The right-hand panel just converts the raw data into indexes with the low-point unemployment rate = 100. This gives you a different perspective and allows you to see the rapidity of the deterioration in a comparable manner.

The three points that stand out are:

- Prior to the end of the cycle the reduction in unemployment rates is very slow (flat section before the low-points).

- Once the labour market deteriorates the rise in unemployment rates is short and sharp;

- The decline in unemployment rates once GDP and employment growth resumes is very drawn out and takes years to make any significant dent in the peak reached at the height of the downturn.

While the rate of deterioration varies a bit, the long-tails are very similar. Having people idle like this for so long is a ridiculous waste of human potential. It is quite obvious that all these workers don’t suddenly get an attack of laziness and drop out of work. The system blasts them out of work as it reacts to a failure of aggregate demand.

In terms of the current cycle, you can see that it is likely to drag out for considerably longer than the preceding recessions in the US over the last 60 years.

The NYT article agrees:

Labor experts say the economy needs 100,000 new jobs a month just to absorb entrants to the labor force. With more than 15 million people officially jobless, even a vigorous recovery is likely to leave an enormous number out of work for years.

Conclusion

Joblessness is real. It damages people and their families for years. In the case of children who grow up in jobless households it can damage them permanently. Society pays a huge cost for leaving people idle in this way – they lose income and become socially excluded.

While the conservatives choose to blame the victims the research evidence is overwhelmingly of the view that system failures (not enough jobs) make it impossible for an individual to signficantly improve their outcomes. What is needed is major government intervention.

Conversely, the whims of the bond traders are just the demands that do not even have to be entertained by any sovereign government. The power that the “markets” exert over governments and the citiznes that elect these governments is beyond all proportion to their actual importance in production and distribution. Somehow, the bond markets have conned us all into believing that they are “important” – that they “add value” and that they “should not be ignored”.

Well the reality is they are unimportant – do not add value and should be definitely ignored. Lets hope there is some movement at the station and governments start standing up to these greedy blackmailers.

That is enough for today.

Here’s a nice easy way to drastically cut the national debt while maintaining demand: stop rolling over the national debt. Easy. Problem solved. The deficit terrorists would be happy (hopefully), as would the MMT lot.

The resulting big expansion in the monetary base MIGHT be inflationary. But in that case just raise taxes to whatever level brings demand back to right level.

In fact I’d go further than that. I think government debt is pretty well pointless. Indeed Milton Friedman said as much: see http://www.jstor.org/pss/1810624 (p.250). Plus Warren Mosler agrees, far as I can see. See http://www.huffingtonpost.com/warren-mosler/proposals-for-the-banking_b_432105.html See immediately under the heading “Proposals for the Treasury”.

Now that’s set the cat amongst the pigeons!

Nice article, but I think you are dead wrong. The bond market will set debt limits for sovereigns. The bond market will set national agenda for countries.

It is happening today in the PIIGS. It will soon happen in other countries in Europe. At some point in the next 24 months this will come to the US. And we will have to bow the “whims” of the bond market. I understand you do not believe this. Put on your seat belt and wait and watch.

Nice to see this post linked to on http://www.nakedcapitalism.com. Hopefully the word is spreading!

The insanity. It is absolutely frightening and frustrating the extent to which U.S. policy makers ignore the significant social costs related to long-term unemployment. The simple solution for them is just to extend unemployment compensation and then ‘hope’ things get better. The Obama Administration not only expects high unemployment for extended periods of time but they ACCEPT it – just take a look at OMB’s unemployment projections. Amazing.

Dear Bruce

I don’t think you have read my work carefully enough. Of-course, governments are at the behest of the bond markets – but only because they voluntarily allow themselves to be. The central bank could eliminate that influence any time the government chose to. The on-going influence reflects the dominant ideology that fiscal policy has to be “market disciplined” and has no basis in the financial characteristics of the monetary system.

Also if you read more carefully I always say that the PIIGS are stuck and are at the behest of the “markets” until they voluntarily exit the EMU and re-establish their sovereignty.

It is not a matter of “belief”. As noted above – until governments abandon the neo-liberal ideology and assert their sovereignty – the bond markets will always hold them to ransom.

The Japanese government effectively called the shots in the early 2000s when the “markets” were rebelling against them (rating agencies). The government then showed us all who had the “power”.

best wishes

bill

Ralph: The resulting big expansion in the monetary base MIGHT be inflationary.

See the debate at Nick Rowe’s place. The simple money supply multiplier model and simple keynesian multiplier model

Bruce: Put on your seat belt and wait and watch.

Bruce, are you planning on going short? Otherwise, you may not like what we are apparently about to witness.

Over-tightening at this point will tank the economy (forget “double-dip”), exacerbate the ongoing deleveraging, and possibly lead to GD II, which was narrowly was avoided by loosening, a money becomes more difficult for debtors to obtain to service their debts and debt-deflation spirals, asset values plunge, and inflation hedges unwind.

This is not only a US problem. It’s global. For example, the Australian housing bubble has yet to burst, and if it does due to tightening, then we’ll see deleveraging in Oz, too, as debt-deflation sets in with the realization that housing prices have peaked and turned down.

Tom: Thanks for the link to “Worthwhile Canadian Initiative”. Normally I find WCI debates reminiscent of theologians arguing about how many angels can dance on a pin head (or perhaps I’m too stupid to understand them). Winterspeak who takes part in the debate describes this particular debate as a “car crash” not worth “rubbernecking” for, i.e. not worth looking at.

See W’s 17th Feb post at: http://www.winterspeak.com/

Anyway if you’ve been thru this debate and found anything that you think I haven’t cottoned onto, can you let me have details? Thanks.

Ralph, I think that the MMT’ers there pretty well demolished the money multiplier, so I don’t know say you assert, “The resulting big expansion in the monetary base MIGHT be inflationary.” The size of base money is immaterial relative to inflation. The big expansion due to the Fed expanding its balance sheet by taking on a lot of bank toxic assets, much of it GSE’s which are now govt. liabilities anyway.

Tom,

Yes, it was a bit of a flurry at WCI stimulated by SRW’s surprising entry. Otherwise, from conversations elsewhere going on simultaneously, I think everyone would have stayed out. In private correspondence with SRW, I think he gets it by and large (that was my impression, anyway) and interested parties were mostly talking past each other. Happens a lot in cyberspace when you can’t just sit down and work it all out over a few beers, as we know.

To Ralph.

I know its just me.

I’ve never gotten above a 4 on the Saturday quiz.

(Tho I thought I should have once).

“The resulting big expansion in the monetary base MIGHT be inflationary.”

Now let’s say the $13T US economy was growing at 2 percent (that is the “non-inflationary, non-deflationary” target after exhaustive metrix-mining by the federal monetary authority), and the GOVUS, acting out on its monetary power, decided to create the $260B via direct payments to banks for federal-budgeted betterments that included dollar for dollar of state-prioritized projects of economic development.

So the GOVUS has, via a method that is non-inflationary by definition, seen to its common-money task of creating money to support the growth in the economy.

THAT, rather than taxing the citizens or borrowing already existing money.

We have $260 B in economic growth and no debts.

Not bad.

Let’s say we had another $260 B in national government debts that were maturing during that year.

That $260 represents previously created monies deposited with the government for safekeeping – it is the bondholders savings.

All they want back is their $260B.

The government repays that $260 B by making a direct cash payment of the monies back to the holders of the debt-securities.

From their savings account at the Treasury-Fed to their checking account.

And we have a big debt-burning party on the capitol mall.

There is no increase or decrease in the money supply.

Just a change from a debt to a credit.

Seems to me Ralph.

How can that be inflationary?

Or am I missing something?

Thanks.

“And what the bond markets require should be irrelevant to a sovereign government. Japan has shown that it can ignore the ideology sliming its way out of the bond markets and the ratings agencies and suit themselves.”

Woah! You’re pretty tough on the bond markets there Bill.

A lot of traders lost a lot of money constantly betting against Japanese government bond yields in the 90s as they went relentlessly lower. I’m sure there was plenty of involuntary unemployment amongst that group.

Ultimately the bond markets will go where they want to go regardless of what a small group of traders think. Bond yields will eventually reflect the appetite that the private sector has for savings in the form of government assets.

Dear Gamma,

“I’m sure there was plenty of involuntary unemployment amongst that group.”

Why were they unemployed? I suspect the involuntariness became voluntary.

I’m sure they could have been immediately employed planting trees or caring for the sick and frail.

But I suppose they didn’t like the pay scale?

Best regards

Graham

Bruce Krasting: “Nice article, but I think you are dead wrong. The bond market will set debt limits for sovereigns. The bond market will set national agenda for countries.”

Not if Andrew Jackson were at the helm. 😉

Let’s look at 10 YR yields:

Japan 1.3%

U.S. 3.7%

U.K. 4.2%

Australia 5.6%

If you want to interpret that as the bond market sending a message about Debt to GDP, then go ahead.

Greece has high yields — 6.5% for 10 YR. But that’s not *that* high, given the fact that Greece is not sovereign in its currency and so the market is pricing in a probability of default on-top of what should be say a 3-4% yield, IMO. Don’t blame the market for adding in that premium — blame the EMU for adding risk where none needed to exist.

RSJ: Japan 1.3%

U.S. 3.7%

U.K. 4.2%

Australia 5.6%

“Oh, the horror of it. Just think what “could” happen once inflationary expectations heat up – which they will any day now with the risk of sovereign default rising so fast.”

Looks to me like the bond market is pretty complacent. No inflationary expectations around here.

Interesting to see Mr Krasting commenting over here. That means you are getting a wider interest and audience. MEEEE LIKEY!!!

Now if only he will stick around long enough to get schooled by you Bill.

Tom: I agree that the multiplier is nonsense. However there is another effect, as follows.

Interest is paid on Treasuries but not (normally) on monetary base. Thus where a chunk of the former is replaced with an equal sized (in dollar terms) chunk of the latter, households’ desired net financial assets will decline. That is, they will tend to spend the difference on consumption and other assets: possibly inflationary.

Or to put that in Warren Mosler “business card” phraseology, parents pay interest to their children in respect of some of the latter’s cards to stop the children spending them. Cease to pay the interest, and the cards will be spent.

A couple of years ago Galbraith at Levy Economics Institute had article on unsustainable surplus, there was these illustrative charts:

http://bayimg.com/image/dakfgaacn.jpg

http://bayimg.com/image/dakfjaacn.jpg

http://bayimg.com/image/hakfgaacn.jpg