I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

The vandals are gathering

Yesterday, the British government announced that they had actually recorded a deficit in January which is rare given they normally get a big revenue boost in that month. The reaction to the news has been hysterical and calls to invoke fiscal austerity measures in the lead up to their national election are gathering pace. You can imagine that these calls are suggesting exactly the opposite of what I think the British government should be doing. Given that they risk locking a generation of their youth into a lifetime of disadvantage, job creation programs are required now which will require further stimulus. That is the only responsible course of action. The bond markets disagree. But if the governments around the world really represented the interests of their citizens they would use their capacities to render all these vandals irrelevant. Most people, however, do not understand what that capacity is and how the government could use it. Anyway, now to the news …

The news that has set all the conservatives off overnight and today is that the British government tax revenue in January dropped (when they normally rise) and spending has risen again. So the government normally runs a surplus in January because of timing issues but this January is the first since 1993 (when records began) that they have borrowed.

So what – is all I said to myself when I read the report.

Things are worse than they expected. The last quarter GDP growth results were barely positive and they followed 6 quarters of negative growth – the longest recession in modern British history. What would you expect to happen?

All I see in the data is that the budget is slightly bigger than everyone thought – which just means the UK economy is in worse shape than they thought. That is the real problem but isn’t mentioned in the flurry of financial data about gilt yields and rating agency threats that has dominated the media reaction to the news.

The graphic below captures the headline in today’s (February 19, 2010) UK Times newspaper, purportedly a quality newspaper that appeals to thinking Britains. It shows how foolish we humans have become in this time of economic crisis.

I read it … re-read it, wondered whether I would see something other that utmost folly in the headline if I stood on my head and read it again then decided that the world is going mad!

The headline has everything – hasn’t it? A terrible budget – and they just can’t help dropping the Greek word, can they?

They fail to mention that they are conflating two incommensurate monetary systems (UK and EMU). That would be too much to ask of them.

Then the sub-heading tells us that the amorphous markets are upset – among them those idiots who waved ten pound notes out of their air-conditioned offices at the demonstrators last year! They are upset. Why should anyone be worried about that.

Then to cap it off – really hitting home (sorry about the pun) – we see a story about why the household budget is even worse than the governments

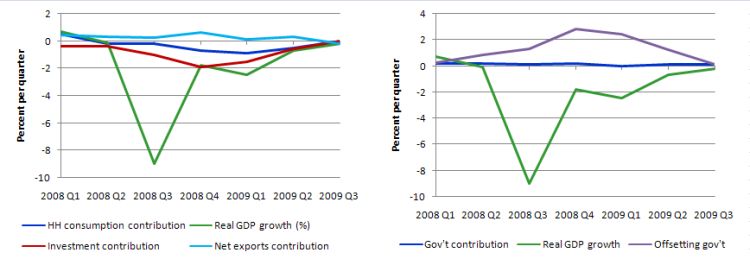

To put this call for austerity into perspective, I had a look at the components of spending in the UK recently. The following graph shows UK real GDP growth on a quarter-to-quarter basis (%) from March 2008 to September 2009 (most recent data). You can get the data from the UK Office of National Statistics.

The other series in the left-panel are the quarterly contributions to growth – household consumption, gross fixed capital formation (investment) and net exports.

You can clearly see that consumption and investment fell in a heap in June 2008 as the financial crisis became a real crisis. The positive contribution shown for net exports is because the decline in imports outweighed the decline in exports and given imports are a leakage from the expenditure stream a contraction is considered “good” for growth.

But the reality is the contraction is consistent with export income falling and domestic growth so low that import spending collapses. Given imports provide benefits the contraction signals a further deterioration in the material living standards of the British people.

The right-panel shows the real GDP growth again but the blue line is the contribution of government consumption spending to real GDP growth over the same period. It has been mildly stimulative throughout the period except for the first quarter 2009 when it made no contribution. So the automatic stabiliser impact on the deficit has been dramatic but the discretionary aspects have provided positive support from output growth.

The purple line (offsetting government) is the contribution that government spending would have had to have made to offset the negative impacts of the contraction in consumption and investment. Even at that level, GDP growth would have been near zero. To have supported GDP growth more fully the discretionary rise in the UK budget deficit needed to be several percentage points of GDP higher than it was.

The actual policy position taken by the UK government has helped but barely.

And now the cretins are thinking that something good will come from a cutback in this support with GDP growth now just above the zero.

Economists disagree

Within this context, there is a battle of economists going on in the UK at present. Last Sunday, a bunch of conservative British economics came out claiming in a grandstanding manner that while they were “non-partisan” [yeh, right!] the “Conservatives’ position” on the need for budget austerity was correct. They said without a plan:

… there is a risk that a loss of confidence in the UK’s economic policy framework will contribute to higher long-term interest rates and/or currency instability, which could undermine the recovery.

Their full letter is HERE. You won’t see any reference to unemployment in their letter. It is all about appeasing the amorphous financial markets as above.

Clearly, I totally disagree with their recommendations and as a test of their sincerity, I suggest they offer to resign their own positions (or if retired, hand back their superannuation entitlements) if the unemployment rate rises as a result of their recommendations which are almost assuredly going to be introduced (in some form) by the spineless British government.

I wonder if they would be so forthright with their arrogance if their jobs were on the line.

Yesterday, not wanting to miss out on the limelight, another group of economists – 50 no less – said the first group was nuts all with that English-type of politeness which I found at when I lived and studied there was actually not very polite at all. The story is HERE.

They said that:

… that the increase in the deficit in the last two years was unavoidable, given that the UK has just experienced the most severe recession since the second world war and GDP has plunged by 6%, forcing emergency government action to prevent the economy “falling off a cliff”.

That point is clear. The deficit would have been much larger and the national debt correspondingly higher if the British government hadn’t have taken some discretionary measures. As I show below the discretionary measures they took were inadequate as a consequence of being spooked by their poor polling in the lead up to the election this year and because they are largely conservative themselves.

One of the second group, David Blanchflower was quoted quoting Keynes (from 1932):

The voices which, in such a conjuncture, tell us that the path of escape is to be found in strict economy and in refraining, wherever possible, from utilising the world’s potential production, are the voices of fools and madmen.

All these discussions about financial markets, yields, ratings and the rest of divert our attention away from the real purpose of the economy – to make things, provide services and provide incomes and dignity to workers. That is the message of this quote.

The financial markets add very little value to our lives. Employment and outputs add significantly. As a sense of priorities, it is madness for us to allow pir politicians to allow concern about these amorphous financial markets (who caused the meltdown in the first place) to usurp our need for employment and income growth.

As I argued in this blog – Who is in charge? – a sovereign government always has the power over the markets!

I note that Paul Krugman is weighing in on his side of the Atlantic in favour of the second group of economists. He said:

I fully agree with the writers’ position. The crucial thing to understand is that fiscal contraction of an additional one or two percent of GDP in the near future has essentially no significance for the sustainability of government finances, either in Britain or here. The only reason to do it is to impress markets – to convince them of your willingness to bear pain. And absent structural reform – which is the real need – how much good does that do?

So let’s not impose useless punishment, there or here.

I agree with those sentiments even though I know Krugman doesn’t really understand how the monetary system operates.

Households and government budgets

In Times story by Ian King – Worried about national debt? Things are worse for Mr and Mrs Average – the author just revealed why he should join the unemployment queue himself. He certainly should not be allowed to write for the public except under the heading of Science Fiction.

King obviously downloaded some data into a spreadsheet and decided it was sensible to pose the question:

The latest figures for the public finances are appalling – or are they? Well, it depends on how you look at them. On a crude comparison with the typical British household, they may not be so bad.

Why? Consider this. According to the Halifax, the average mortgage outstanding on a UK home is £112,000. According to figures published by the Office for National Statistics on Wednesday, average regular pay now stands at £425 per week, or £22,100 per year.

In other words, a typical UK household containing one wage earner on average pay has outstanding long-term debts equal to 507 per cent of annual income. By comparison, the Government’s income for 2009-10 is expected to be £498.1 billion, against the current national debt of £848.5 billion. So the Government, with a debt of 170 per cent of its expected income this year, is comparatively better off. The comparison is slightly spurious: the homeowner owes money to his mortgage lender, while Britain largely owes money to itself, largely in the form of pension funds.

Don’t you just love it … “the comparison is slightly spurious”. Sorry, the comparison is totally spurious and has no foundation in any knowledge system that is reasonable.

The homeowner is financially constrained and will have to sacrifice spending or sell assets to repay the debts. They use the Sterling! The British government is not remotely in this situation and never has to sacrifice other spending to repay its debts. It issues the Sterling!

If we can just get that message out today then there will be progress in the public debate.

Repeat: a budget of a sovereign government is never similar to that of a household. They can never be compared and the principles and behaviours that restrict the latter have no application to the former.

King though was intent, and after noting that households who can pay their debts will not be foreclosed (duh!), he says:

… And that’s the point. A debt only becomes an issue when you can no longer meet the payments on it. This, unfortunately, is why many global investors are now raising the alarm over the UK’s finances. The national debt may be under control for now, but the budget deficit – the shortfall between what the Government spends and what it rakes in – is adding to it all the time, potentially pushing up the cost of servicing the nation’s debts in future to perilously high levels.

What exactly are perilously high levels of national debt? How does King define that? In relation to what? How worried are these unnamed investors?

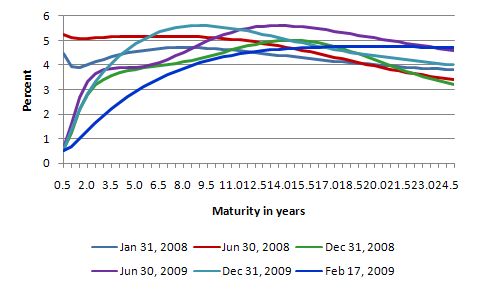

The other day in this blog – A modern monetary theory lullaby – I showed that the US yield curve (for government debt) was not budging despite all the hysterics that bond dealers are worried and about to close the US government down.

So what is going on with the UK yield curve?

You can get a huge amount of yield curve data from the Bank of England and this resource base is one of my favourite haunts. You can also learn about yield curve terminology HERE.

The BoE compiles the yield curve data on a daily basis and you can get the yields for UK government bonds (gilts) and the “sterling interbank rates (LIBOR) and on yields on instruments linked to LIBOR, short sterling futures, forward rate agreements and LIBOR-based interest rate swaps”.

From the UK Debt Management Office we read:

A gilt is a UK Government liability in sterling, issued by HM Treasury and listed on the London Stock Exchange. The term “gilt” or “gilt-edged security” is a reference to the primary characteristic of gilts as an investment: their security. This is a reflection of the fact that the British Government has never failed to make interest or principal payments on gilts as they fall due.

Repeat: “never failed to make interest or principal payments on gilts as they fall due”. End of story.

The following graph shows the instantaneous normal forward curve (nominal) for UK gilts for selected month-ends and yesterday since early 2008. We see a bit of movement at the short-end as the BoE cut rates and some movement at the long end as it’s QE program boosted the demand for long-term gilts (driving the price up and yields down). There has been some slight upward movement in recent months at the long end but nothing to signal an immediate end to the world as we know it.

But it remains that the UK is being forced to pay higher yields than even some EMU nations. This demonstrates the irrationality of the bond markets. Yesterday the German 10-year bond was offering lower yields (by about a percentage point) than the UK. The former as part of the EMU is exposed to insolvency and that risk has risen in recent weeks, while the latter (the UK) can never be insolvent and as they say above has never defaulted on a gilt.

Further, Portugal’s 10-year bond yield is less than 500 basis points above the UK’s. The former is very exposed to insolvency. So go figure. These markets get things wrong all the time – witness the global meltdown – it was all their own work!

In closing this section on households and governments, I note that the deficit terrorists in the US – via the Peter Peterson Foundation – are promoting Budget Ball which they describe as “a new sport developed to raise fiscal awareness, will debut on college campuses this spring starting with the University of Miami and Philander Smith College in Little Rock, Arkansas”.

It is a concocted way of brainwashing US university students into believing their personal finances are the same as the US governments. It is just sinister the lengths the conservatives will go to to reinforce their elite position. I am sure none of the Wall Street bankers who had their hands out would have gone to a budget ball game at the time.

I advise all students to boycott those tertiary institutions if you value your intellectual development and have any semblance of self-respect left.

The word from the BIS

In relation to the bond markets, I thought a paper that I read the other week from the BIS was salient.

In a speech last December – Unwinding public interventions after the crisis – a senior official at the Bank of International Settlements (the central bankers bank) told the gathering (of IMF officials) that:

The leverage-led growth model – a combination of excessive leverage in the financial system, overindebtedness of households, low interest rates and global imbalances – was at the heart of the crisis.

But the paradox is that the policies that have been adopted to remedy the crisis consist, all in all, of even more of the same: borrowing, debt, leverage.

Of-course, he didn’t make the distinction between private and public debt. It was as if the two are identical. They are not. Please read my blog – Debt is not debt – for more discussion on this point.

The BIS speaker went on to argue that we might be at risk because the output gaps may be less than we think. This is one of those debates that emerged in the 1970s where the conservatives claimed that things were not as bad in real terms during the stagflationary period. At present, the best measure of the real damage of the crisis is the labour market – that is the people-measure.

And unless the BLS and other national agencies around the World are lying (and I know there are lots of conspiracy theorists out there who think the national agencies do lie – they don’t!) then things are very bad at present.

But the BIS claim that upon this basis:

The dominant view (“it is too soon to tighten”) is highly questionable. Postponing the fiscal adjustment to a time when the recovery has consolidated may not be sustainable. Inaction and postponement could prove a risky policy.

Simply communicating on the design of future medium-term frameworks for consolidation may calm the rating agencies for a while but does not address the mounting concerns in the bond markets about fiscal solvency in the medium to long term.

There is a need to be mindful of where we are in the business cycle and to think ahead as to which aspects of the stimulus can be withdrawn and when. But we are so far from being close to an inflationary breakout that there is no upside risk at present.

The fact is that the fiscal support was too conservative anyway by several percentage points of GDP – so there was already a “withdrawal” from the outset compared to what should have been.

And as Japan showed in the 1990s, the ratings agencies are irrelevant to sovereign governments. I would outlaw them.

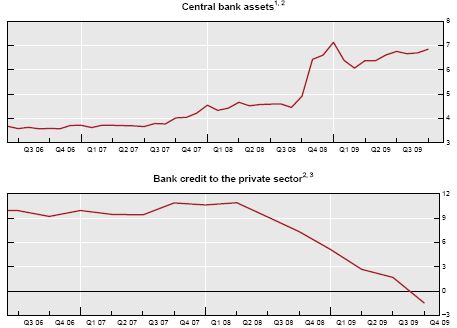

But the interesting point of the paper (which is why I am referring to it here at all) relates to the following comments on “central banks’ unconventional balance sheet policies”. In other words, the paper is addressing the aspects of monetary policy that go beyond setting the short-term interest rate which have emerged in the currenc crisis.

The BIS said:

Exiting from the outright asset purchases will be more challenging. Given the potential impact on asset prices, central banks may be tempted not to sell but to adopt a “buy and hold” stance. However, the key issue here relates to the potential role of central banks in directly influencing long-term bond yields and credit spreads: market participants should be under no illusion that we are entering into a new permanent accommodative monetary policy regime in which central banks would be able and willing to control the entire length of yield curves as well as credit spreads and mortgage rates. The unconventional measures should not be seen as an additional set of tools that central banks would use in their normal day-to-day conduct of policy.

In normal times, central banks will need to go back to their usual approach of controlling only the short end of the yield curve and of refraining from interventions with potential distorting effects on relative asset prices. Exiting from unconventional monetary policy is necessary to make clear that the unconventional will not become the new normal. The sooner the exit, the better.

This is an important issue that needs to be debated. What they are saying is the central bank can control the entire yield curve – as I explained in the blog – Who is in charge?.

In other words, all the angst about bond markets rehearsed by the commentators above is unnecessary. If the British government or any government is paying yields on their debt higher than they think is desirable then they can simply instruct the central bank (or change legislation to allow them to do so) to manage the yield curve.

The fact that central banks do not do this reflects the ideological position that monetary policy should be targeted at fighting inflation (with no particular regard for the real consequences – given they believe in the NAIRU myth) and that fiscal policy should be a passive partner in this unemployment-creating folly.

If governments started to use the capacity of their central bank operations to control longer-term yields then the bond markets, the rating agencies and all the rest of these self-serving forces – become totally irrelevant.

But then monetary policy would have to cede authority to fiscal policy. Which from the modern monetary perspective is how it should be. We would then be able to target higher employment growth and use fiscal policy to contain inflation.

The next step would be for national governments to just stop issuing debt altogether.

As an aside, the paper produced this graph which should disabuse those who consider the build up of reserves will boost bank loans. Please read my blogs – Building bank reserves will not expand credit and Building bank reserves is not inflationary – for more discussion on this point.

Conclusion

It would be madness for the British government election notwithstanding to make any net budget cuts at all. Given the appalling state of their economy they actually need further government stimulus not less.

I will finish today with another of Keynes’ famous statements that Blanchflower could have easily quoted also:

The Conservative belief that there is some law of nature which prevents men from being employed, that it is ‘rash’ to employ men, and that it is financially ‘sound’ to maintain a tenth of the population in idleness is crazily improbable — the sort of thing which no man could believe who had not had his head fuddled with nonsense for years and years

Saturday Quiz

The Quiz will be back again tomorrow sometime – it will be only a few hundred words in length but torrid! 🙂

That is just enough for today.

Bill, you repeatedly fail to address several criticisms I have of you model. Inherent in your model is the concept of sticky prices and wages is not the natural order of economics. But as I agree with the accounting constructs within MMT I am also wary of it as an oversimplification of economics. More specifically, I see the massive flaw being the failure to discern between the real and the nominal economy.

Your goal as far as I can tell is to use MMT as a tool to explain how full employment (whatever that means) can be obtained while also maintaining nominal output. If that is in fact your goal I see no real flaw in your argument, at least in the medium term (at some point it seems mathematically possible that, as govts run deficits to make up for a continuously de-levering private sector, interest payments will eventually exceed output). But I think you fail to discern between the real, wealth generating economy and the nominal economy. Neither Keynsian not Monetarists really get this either. The failure is really a failure to understand that money is just a way for us to keep score relative to our peers and is really not a good absolute measure of anything. For if we hire unemployed workers to break down Detroit brick by brick and they rebuild it we may be nominally richer but we are poorer in reality. That is because the same miserable institutions will remain there ensuring that the return on that particular investment is very small or at least much smaller than it would have been had all the materials been used in an economic venture.

Obviously there are friction costs (people may have to relocate, retrain, or get creative to find or make work) but the market mechanism has repeatedly proven itself to be superior to central planing throughout history. Furthermore, price signals, in this case the falling price of labor, capital, and materials that would likely occur without govt deficit spending, would work to encourage innovation and re-application of the excess labor/goods/capital. Meanwhile, during the period of slack (excess labor/goods/resources) those in our society who use those resources will be able to either use more of them or maintain their previous use while having more to spend on new good and services. Maybe those who see their costs coming down will choose to “spend” more on leisure- wouldn’t that be more optimal than socialist work-week mandates?

I see this as a moral issue and I fear how the MMT will be co-opted by Collectivists everywhere.

“The next step would be for national governments to just stop issuing debt altogether.”

Would you just use fiscal policy to manage the quantity of money in the economy? Would this adequately deal with bank reserves? No need for ‘open market operations’?

Would just having a government bank work?

Yossarian,

One point I would make is that under a balance sheet recession when the private sector is paying down debt, if the government does not intervene with nominal spending then the private sector will strangle itself because it will be competing for a diminishing amount of “flowing” money. By this I mean that as private debt is repaid, this pulls nominal demand out of the system. The banks will try to relend what has been repaid but owing to the bad decisions made by the private sector previously the private sector will not borrow and spend any of this repaid cash as it is desperate to try and pay down more of the debt it mistakenly took on and previously invested in unproductive assets that have declined in value (this could be various things – in Japan’s case it was real estate).

So the this debt repayment is basically like nominal demand leaking out of the economy, which causes the private sector to try and extract money (profits might be a better term) from an increasingly small pie, while the debt repayments that are made just pile up in the banking system. Since the private sector as a whole is trying to pay down debt it will be self defeating. Nominal demand will continue to fall as each over indebted entity tries to extract some of its income to pay down debt leaving less circulating each time which reduces the income of the other entities who themselves try harder to extract some of their own income for debt repayment until eventually they all become so poor that they can’t afford to save any of their income for debt repayment. Of course nominally this will cause a fall in the price level, so that in real terms things are not quite as dire. This was the case in the great depression in the USA where between 1929 and 1933 prices fell around 30%. But output will always fall faster than prices in this case and since the price declines are being caused by a collapse in demand instead of an expansion in supply, it is not a situation to be desired.

You could argue that these businesses should go bankrupt if they cannot compete, but here it is not an issue of business being unprofitable. In Japan’s case most businesses that were paying down debt were still very profitable, efficient and providing useful services to their customers in the 1990s and early 2000s. However the mere fact that they were all trying to deleverage at the same time was causing these efficient and profitable (under normal steady demand conditions) enterprises to be of risk of bankruptcy because their nominal assets were less than liabilities.

The only way to facilitate the private sector’s desire to save is for the government to run big deficits to at least match the level of debt repayment of the private sector. The goal here is to help the private sector do what it wants to do, which is something that someone with such anti-collectivist views as you should be able to appreciate. The government is the entity that issues the currency so it is the only entity that can allow the private sector to repair its balance sheet in nominal terms. Again you could argue that demand collapse deflation would function as a price-signal to the private sector to invest etc., but the raw fact of the matter is that that theological efficient market theory does not reflect what happens in reality. No matter how low interest rates go, once the private sector as a whole gets into the balance sheet mindset it will continue to pay down debt and reduce expenditures until it has cleaned up its balance sheet. Richard Koo has empirically documented this is his book, The Holy Grail of Macroeconomics, which although it is not chartalist, I strongly recommend you read. It has clearly been shown in Japan that “price-signals” did not work to drive up private sector demand after Japan entered a balance sheet recession, in fact it was the private sector as a whole that caused these “price-signals” to manifest themselves because it was acting collectively in a self-defeating (as long as there is no government spending to spend at least as much as the private sector pays down in debt) fashion. In this case the private sector does not react to the signal, the signal is merely a reflection of the fact that the private sector is not acting as neo-classical theory says it always should. In a balance sheet recession (as empirically demonstrated in Japan and the great depression) the private sector will pay down debt even in the face of almost zero interest rates and other “price-signals”. It will no longer be in profit-maximization mode, but in debt reduction mode.

Your argument basically amounts to the liquidationist argument at the beginning of the great depression. That the excess would be purged and that as prices fell demand and investment would pick up. But you fail to understand that the private sector just doesn’t work like that in reality. It’s empirically false, as demonstrated in the great depression and in Japan’s long period of private sector balance sheet repair. I wish the private sector really did react as you and the liquidationists suggest, as it would save an awful lot of trouble and we would live in a world closer to an “efficient” textbook reality. But empirically and undeniably, we do not. Again if you do not take my claims at face value, then please read Mr. Koo’s book.

As for the issue of collectivism and individualism, I would point you to Japan, which has an extremely collectivist society and is quite frankly the most civilised society in the world. Murders are 7 times less than in the law of the jungle USA (though only sometime like 2 times less than the level of most European countries which are mostly mid-way in outlook between the individualism of the USA and the collectivism of Japan). Both unemployment and inflation have been consistently lower in Japan in the post-war period than in the USA. There are almost no strikes in Japan, because workers are loyal to their companies which provide them with long term employment and seniority based pay. The abuse of public property that takes place in the recklessly individualist western countries is almost non-existent in Japan, as Japanese are raised to put the needs of the group above their own selfishness. There is a deep sense of responsibility in Japanese for upholding the honour of the group(s) that they are members of and they emphasise extreme modesty and acceptance of shame upon failure to meet expected standard’s of conduct. This is a beautiful contrast to the egoism and endless selfishness that is promoted in the USA.

I would recommend you visit Japan should you wish to see the blatant triumph of collectivism over individualism. The contrast between the social collapse, inequality, crime rampant USA (the only developed country that doesn’t even provide health insurance for all its citisens) and Japan is shocking. In fact I don’t think the USA is really even a developed country, because it has failed to develop a civilised society. American’s are raised to be selfish and grab as much as they can, even taught that this is some sort of moral virtue. On top of that 25% of them that are Christian fanatics and a third of them are not just overweight but obese, actually eating themselves to death. This is what happens when you encourage humans to turn to their most base and animal instincts, and Japan is what happens when you encourage the human aspect of humans while resisting the animalistic tendencies.

Collectivism has empirically won.

Dear Yossarian

I have two arms, two legs and less than 24 hours in a day to attend to this task. I am also not a answer-on-demand service.

I have noted your concerns (expressed several times – once was enough) and will answer them when I have time.

best wishes

bill

-So we have uncovered the underlying subtext of the MMT theory: that Collectivism is necessary to be a developed, civilized nation. If that is your view, fine: but don’t impose it on a nation that has risen from a nation of paupers rejected by European aristocracy to become the most powerful and prosperous in the world DESPITE continuous and escalating efforts by the Collectivists to hold them back.

-If you want to make this a Nationalist debate I will play along, even though I have been to Japan several times and enjoyed it very much. If you look at suicide rates you will find many Collectivist nations on the top (a)- I believe it saps your humanity (b). Although it can be useful- it worked well for a while until WWII but we all know how that turned out. But back to the undeveloped, cruel nation that is the USA- we are the most charitable nation in the world when we’re not forced into govt-mandated charity (c). Through invention, production, and marketing The US has contributed more to human advancement in the last two centuries than any other nation. Certainly the great soil of individual liberty and personal responsibility that spawned this great nation is eroding; however we should not facilitate that erosion with Collectivism but rather infuse the soil with what made it great in the first place: Liberty. Oh, and the fattest nation in the world is now Australia but I hope The USA can retain the title soon. Although if you really examined how those studies are done you would laugh at them (just like WHO studies on healthcare).

(a) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_suicide_rate#cite_note-1

(b) http://www.atimes.com/atimes/Global_Economy/LA05Dj06.html

(c) http://www.cafonline.org/pdf/International%20%20Giving%20highlights.pdf

-I care not a whit about inequality unless it’s due to the institutional structures put in place by the collectivists. The beneficiaries of such institutional subsidies include lobbyists and their clients, 2BTF financial institutions, certain govt employees, lawyers, etc. The fact is, inequality is very mobile in a free society as people move up or down the income scale (unless they are bailed out and/or sheltered from competition). I can’t tell you how many RE brokers I know who went from very rich to poor (I mean no income) in one year’s time. The more flexible the economy, the more likely this is to be the case.

-I have no desire to satisfy your wish to impose a “great moderation” on every aspect of our social and economic life. Getting paid to do something that you know isn’t adding value is bad for self-esteem- it’s akin to begging- it may sustain you but it’s unhealthy. I’ve been in a steady, safe job and felt that guilt- it was hard to take a risk and make a move but I did and I am much happier for it. Sometimes the market has to tell you that you aren’t adding value and should be looking harder for a way to do so.

-There is no such thing as this declining spiral of deflation into some black hole where nobody works or consumes, factories all close, and life stops. The fact is people consume goods because they utility from them, regardless of whether they will be 2-3% cheaper in one year’s time.

-My favorite Depression is the one that didn’t happen in 1920-21 when output dropped by up to 7%, consumer prices dropped by 18%, and wholesale prices dropped by 37%.

-We have been entrenched int he nonsense inflationary system and we must acknowledge it a failure. Our policies must involve facilitating the unwind without permanently increasing the role of the public sector in the capital allocation process. Perhaps the inherent inflation is so large that some sort of cushion must be put in place but I think most focus should be paid to reforming the institutional mechanisms that hinder private sector solutions (why can’t Bill Gates or anyone else buy a controlling interest in a bank?). Focus on streamlining the bankruptcy process.

Yossarian: I am also wary of it as an oversimplification of economics. I am also wary of it as an oversimplification of economics.

Uh, it is an oversimplification by design. Econ 101 is an oversimplification. Introductory macro is an oversimplification. All economists admit this. But you have to start with simple concepts and build on them. That is what Bill is doing regarding how a modern (post-1971) monetary system operates. The MMT approach to macro gets very complex very quickly. Go read some articles and books if you need convincing.

More specifically, I see the massive flaw being the failure to discern between the real and the nominal economy.

The basis of MMT is showing how the monetary system (“monetary economy”) and real economy relate to each other, and to policy. This is what accounting does for a real economy entity, whatever its nature, and it is what monetary-based macro does for the real economy as a whole. Take a look at how the model develops in Godley and Lavoie, Monetary Economics. They use successively complex models to illustrate modeling the changes in stocks and flows numerically to represent the changes in the real economy in terms of reported data.

Obviously, stock-flow consistent accounting is important for management of any economic entity, but it is not the sum total of management. As you point out, numbers don’t capture everything. They are good for reporting quantities but not so good for dealing with quality, for example.

There is also a gap between economics and the real economy because of imprecise data. All macroeconomic data are approximations. Collecting, processing and reporting data is time-consuming and expensive. The US government does a better job than most, but it is far from perfect.

I see this as a moral issue and I fear how the MMT will be co-opted by Collectivists everywhere.

Really? You mean that liberals and progressives, the public, and the media will discover the truth of how the monetary system works and use it to promote the general welfare? Well, that’s the plan some of us have anyway. I assume you want people left in the dark by the conservative misrepresentations that limit the role of government and put workers at a disadvantage due to public ignorance of complex subjects and the disingenuousness at the top of the food chain that promotes this ignorance actively through an ongoing propaganda campaign. How well has this all worked for the middle class and poor over the past several decades of predominantly conservative economic policy, in contrast to how the wealthy fared because of it?

Since I am new here and don’t want to cause any problems I will ignore Yossarian’s Randian rant and just ask a question:

If gov’t decided to NOT issue bonds would that deprive the economy of financial assets and a “risk free” rate for CAPM (too bad for those who still believe in that)?

If gov’t decided to NOT issue bonds would that deprive the economy of financial assets and a “risk free” rate for CAPM (too bad for those who still believe in that)?

1. It would not deprive non-government of NFA. NFA are created by currency issuance (less taxation) and would remain liquid or seek another haven instead of being transferred into Tsy’s.

2. You would hear a loud cry of protest from the wealthy, who are accustomed to a safe haven parking place that pays them to park there.

Tom –

Thank you for your response. Theoretically I agree that gov’t could stop issuing bonds but we are talking serious implications for interest rates which translates to cost of consumer credit for working class families. I am trying to think this through.

we are talking serious implications for interest rates which translates to cost of consumer credit for working class families.

The overnight rate is virtually zero and credit card rates are pushing 30% for consumers without excellent credit. Where’s the connection?

The Fed is also showing that it controls the yield curve also, keeping L-T rates under its control by expanding its balance sheet by buying securities, chiefly MBS.

Yossarian wrote:

MMT, in itself, is non-committal on ideological matters, as any legitimate economic theory should be. It does not follow from MMT that more government is better than less. It does not even follow that low unemployment is better than high unemployment. These are political choices. Once society determines the direction in which it wants to move, MMT indicates the options available under a modern monetary system.

If society wants an economy dominated by private-sector activity and a retention of business-cycle fluctuations on the grounds that it spurs innovation, structural adjustment, or whatever, that is an option. MMT indicates that this will create fairly regular periods of mass unemployment. If society wants to shield workers from the brunt of business-cycle effects, MMT shows that it can do so through a job guarantee. However, if society does not wish to shield workers from the brunt of business-cycle effects this is also an option. MMT does not cast judgment on that choice. It is a political matter up to the community to resolve.

Likewise, if society opts for a more substantial role for government, including business-cycle stabilisation, public-sector provision of some goods and services, or even a move toward socialism, MMT indicates the options available under the existing monetary system. But MMT is silent on whether these choices would be good or bad.

It is not the role of a legitimate economic theory to start from an ideological position, and then cast everything in terms of that ideological judgment. I realise this is what neoclassical macroeconomics does. It starts from the ideological position that there is no role for government unless it can be established that there is an externality or market failure that cannot be addressed through a market solution. The rationale for this decision rule is purely ideological, and not at all scientific. The theory’s ideological nature largely explains why it has remained dominant in academia and policy circles, despite having been thoroughly discredited on logical grounds. Like neoclassical economists, some appear to want a theory that favours their particular brand of “morals”. That is scientifically unacceptable. They should start a church if that’s the way they wish to proceed with their economic analysis.

It is transparent why they prefer such a dishonest approach. They fear that if the system is presented as it is, without all the obfuscation, mystification, misinformation, etc., society as a whole might turn out to make different ideological judgments than they would like.

Tom: I want to thank you for taking the time to post so many great comments. They add substantial educational value to Bill’s already exceptional blog. I consider Bill’s posts and your comments to be must reading each day. Cheers.

Tom –

You are right about the current situation but I think that is more of a function of credit card companies showing the public “fine if you want regulation this is what it will cost you” type of thing – more bluster than anything else – once things ‘normalize’ rates go down a little (however this also could depend on securitization market).

The fed is controlling the yield curve but as Prof. Mitchell says the issue of whether this continues is an ideological one.

As for my concern, if we eliminate a huge portion from an asset class (fixed income), at the very least we are adding a significant cost to something like hedging risk for lenders which may add to cost of credit. Your thoughts?

Alienated: thx and I believe I understand MMT. However this is very much an ideological blog whereby MMT is the base with which to build a theoretical construct to advocate the role of govt in ensuring full employment and preventing price deflation and any decline in nominal output. I am arguing against the ideological agenda that is using MMT as their basis, admittedly on behalf of my own (in my view far superior) ideological agenda. So on behalf of my agenda here are my response:

-Really Tom Hickey, if the people understood MMT they would break off from the Conservative-imposed shackles of limited government and score one for the little guy? In what way has govt growth been limited? The total govt expenditures as a % of GDP has rising continuously in the US from about 5% in the early 1900’s to around 35% pre-crisis (I will ignore the latest explosion to 45%). This whole process has not been enabled by any conservative ideology. Less directly, the mainstream (from Krugman to Friedman) failure to tolerate any economic contraction (I say reorganization is a better term) and the belief that inflation is necessary for economic growth has caused both the unjust income disparities (note, I have no problem with the JUST income disparities as evidenced Steve Jobs, etc.) and the growth in the public role in the allocation of private resources. When you have inflation it is not the weak who benefit but the wealthy- those who own assets and have access to credit and the associated purchasing power before the value is eroded. Those who suffer are wage-earners and seniors on fixed-income as well as diligent savers of capital. The main beneficiaries of an inflationary environment are the financiers, governments (who realize increasing revenues), and those associated with them. It is my ideology, not your’s, which is in the interest of the (motivated) little guy.

-Furthermore, even when the cycle-smoothing solutions make sense in theory, the implementations render them deeply flawed and often wasteful. Before you say the unemployed are wasteful human capital I will say that you fail to understand the process- many can find work but are reluctant to acknowledge that their skill set is not worth quite as much as they once thought. Or they are waiting to re-apply their skill set to a new endeavour. Your Macro theories fail to understand the Micro.

“The curious task of economics is to demonstrate to men how little they really know about what they imagine they can design.”

“Before you say the unemployed are wasteful human capital I will say that you fail to understand the process- many can find work but are reluctant to acknowledge that their skill set is not worth quite as much as they once thought. ” – Yossarian

As one of those unemployed, I must say it’s not that my skill set isn’t worth as much as I once thought, it’s that I will have to start lying on my resume because I am considered “overqualified” for the jobs available in my area. Employers (those that are hiring, anyway) are looking for specific types of workers. My resumes get thrown out (or tossed to the bottom of the heap – I’ve done this myself when I was a manager) because they don’t want to take a chance on me. They naturally assume I will find another higher paying job when the opportunity arises. So here I sit in my forced wait; waiting to reapply my skill set to a new endeavor. Watching as my savings dwindles and hoping I don’t get sick because I have no health insurance.

Tell me, Yossarian, do you think it ethical that I start lying in order to get hired? Do you think I can migrate to other areas with little cost? Or do you not really understand the Micro as much as you think?

Here’s an idea Yossarian. Go back to school. Learn some economics. Only this time sprinkle in some human compassion.

As for my concern, if we eliminate a huge portion from an asset class (fixed income), at the very least we are adding a significant cost to something like hedging risk for lenders which may add to cost of credit. Your thoughts?

The cost of credit is the price of money. As far as I understand the MMT approach to macro, price determination takes place on the basis of supply and demand, except in cases in which the government intervenes, e..g, in fixing a target rate in the overnight interbank market for reserves, or by controlling the yield curve through market intervention. Some MMT’er anyway think that the government should use fiscal means instead and let the market established interest rates based on supply and demand.

BTW, a lot of consumers are now discovering that they can get a lot better deal as credit unions than big banks. This remains a competitive market.

Yossarian, we can argue about this ideologically all day, but that is independent of MMT. MMT is just an operational description and setting forth of options based on consequences. Bill has made clear that while the principles of MMT are value-free, his views about the options that MMT presents are not. I am in agreement with these views. You are not. Fine.

I’m here to try to understand MMT better from a person who is an expert. I make no pretense about knowing anything in depth about economics, finance, or this field. I do not. I’m really not interested in debating politics, ideology or values/norms here. There are other venues specifically devoted to that.

Right now, the conservatives hold sway in the US and have passed legislative constraints on fiscal policy that mimic a convertible fixed rate currency. Given your stance, you should be lobbying to keep those, while I lobby to have them removed, given mine. It is unlikely that you will convince me to convert to your policy position, or at least to modify it, as it is unlikely that I will convince you to convert to mine, or get you to change it.

Learn some economics. Only this time sprinkle in some human compassion.

Interview with economist Jeremy Rifkin, author of The Empathic Civilization, in New Scientist speaks to this.

Yossarian, when you say “The total govt expenditures as a % of GDP has rising continuously in the US from about 5% in the early 1900’s to around 35% pre-crisis (I will ignore the latest explosion to 45%)” what can your government show for this money? Endless wars all over the world. Take any western European government where 45% is rather a norm than exception however any of them will be able to show much more for this money to its citizens. I am happy paying these taxes because I know what I get for it.

Then you say collectivism suffers from suicide rates and it might be true as a fact. However bad it might be but this violence does not violate freedom of other people as murders obviously do. A suicide for Japanese people is definitely a cultural thing which goes back in time when it was done for reasons other than collectivism, i.e. honour. Even more it is the culture of Japan which makes non-contractual law so binding and the punishment for any violation used to be self-imposed. Now compare this to Anglo-Saxon world where lying is normal and written contracts are subject to dispute in pursuit of simple profit. So while you might be right about pure statistics the reasons of it might be completely different.

OK, suicide=honor. Got it- this is apparently a cultural difference that can’t be bridged between us.

KT, I’m sorry you are out of a job- I was expecting the same and am oddly somewhat disappointed that I didn’t get let go along with the other half of my company last year. I have a comfortable job yet I am not happy because I know I am not adding value commensurate with my potential. I made the wise decision to save rather than partake in what I thought was an obvious real estate mania and by doing that I bought the ultimate: piece of mind and flexibility. Being 30 I thought I would go to China to teach English and learn Chinese, maybe take some computer programming courses and figure out my next step. But figuring out my next move is a much slower process and, in my view, being let go would be the best thing that could happen to me as I am reluctant to forgo a good salary in this economy.

But tell me, what is it that you do and what is your background that renders you so “over-qualified?” Have you thought of perhaps starting your own business? In BillyBlog utopia what kind of employment would the government (actually me, the taxpayer) be offering you? Would this be a permanent career or temporary? While I’m glad you can afford a computer and $100/month in internet access I would prefer you use that money to purchase health insurance which could be had for only a few hundred $$$ in states like Wisconsin. Maybe if you worked at WalMart instead of reading BillyBlog and watching Kieth Olbermann you would be able to purchase such a plan. Or perhaps you can even get the taxpayer to take care of you via Medicaid. You are strong and will figure out a way to survive- I believe in you!

And Sergei, I don’t wish to debate the foreign policy of the US as it is far too interventionist for my liking. I would though like to thank all the Euros and Canadians out there who continue to bash the US while piggybacking on the security the US provides. As a US taxpayer I must say I really enjoy sparing the Canadian and European taxpayer the burden of defending themselves as they are obviously far too weak and feeble to do the job themselves. At least the Japanese were appreciative for a while.

Yossarian, you need to read billyblog more closely and realize that you (the taxpayer) are not funding anything when government disburses funds, because government currency issuance in a fiat regime is neither funded by taxes not financed by debt. That is just an illusion in which you are still trapped due to your own (willful?) ignorance. You are just mouthing the conventional wisdom that happens to be nonsense economically. Get a grip.

Moreover, you have a bad attitude and need to work on it. It’s called mental hygiene. No one likes M.O. any more than they like B. O. Learn to speak the sweet truth, or your troll-like behavior is going to get you ignored here. We are trying to help each other. That was really rude the way you dissed KT, who is obviously hurting already. Who are you to sanctimoniously tell him what you prefer him to do? Play nice.

No, Tom, it is you who are willfully ignorant of what money is. There is a certain quantity of goods and services produced within an economy and money is a claim on that “stuff.” The government doesn’t create any stuff, despite the fact that they can issue claims on that stuff by fiat. Essentially they are counterfeiters. Although the productive citizens of this nation will tolerate such counterfeiting when they feel the end use is reasonable, in no way does that imply that it is costless. In essence what happens is that government is taking away (or diluting) Peter’s claim on an economy’s resources and giving the claim on those resources to Paul. Of course the govts ability to spend is limitless in a fiat money regime as long as you assume that this fiat power will be respected. But the problem is people can see that they are being robbed and are not happy about it. You, Tom, are the robber in many people’s eyes including myself.

Dear Yossarian (and Tom)

Please keep the interchanges civil.

As to Tom being a “robber” – he is a household in a macroeconomic sense and relies on the government to spend before he can pay his taxes (when you distil all the accounting down).

It is certainly true that sovereign governments use their currency to “take” real resources from the private sector and redistribute them to further their socio-economic policy. So what? They have economies of scale and positional advantages that allow them to deliver benefits to society that individuals could not achieve themselves.

As to whether the “fiat power is respected” – there are not many historical examples where a sovereign government has not been “respected” in the sense that people accept its spending to gain access to its currency. They are extremes and usually in the gold standard period.

Yossarian, I also recommend you have a bit of a holiday and travel to the Great Ocean Road in Victoria, Australia, which was cut out of the cliffs by government employment programs during the 1930s. The “private sector” would never have created this resource and it is now worth billions in revenue to the private economy via tourism. That should teach you that governments can create value. But then there are many examples in the US of this sort of initiative.

Anyway, we have heard your opinion – it does not reflect an understanding of the way the monetary system functions. So I suggest you read further and try to extend your understanding without jumping to conclusions and/or rehearsing the old political cliches that take us back to accusations of “dictators” etc.

best wishes

bill