I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Its a hard road

As one dead-end traps the mainstream deficit terrorists’ relentless “hyperinflation is coming”, “the deficits are large and unsustainable” campaign another road is opened. New ways are found of pushing the same boring message. I read several papers and article today that all try to come up with a new tack – a new way of scaring the bjesus out of us and steer our minds towards what they assert is misguided government policy. They actually just don’t like any government claim on real resources because they think there is less for them then. Even when they don’t want to create jobs for the unemployed they resent government employing these people because it would just be a “waste of resources”. Its got worse as I read on. I tell you keeping up with all this stuff is surely going to be “a hard road till I die”.

Musical title credit for today comes from the great John Mayall and the Bluesbreakers song A Hard Road (second album in the table shown). This was recorded on epoymous album from 1967 and featured the great Peter Green on guitar, who left the Bluesbreakers soon after to start Fleetwood Mac (bass player on the Hard Road album was John McVie who eventually also left Mayall’s band to play in Fleetwood Mac. The verse where the title credit appears goes:

I been tryin’ to tell you people

That the blues hit me in my life

You know I was born for trouble

And it’s a hard road till I die

I just thought you might like a bit of a musical diversion before we start today because it is going to be a very hard road until we finish.

Now first of all a legal matter.

In Australia, it is an offence to deface or mutilate the fiat currency instrument (notes and coins) in any way. So I had assumed it was the same for the US. I did some research. According to the statute Title 18 United States Code, Section 331 which covers the Mutilation, diminution, and falsification of coins:

Whoever fraudulently alters, defaces, mutilates, impairs, diminishes, falsifies, scales or lightens any of the coins coined at the mints of the United States, or any foreign coins which are by law made current or are in actual use or circulation as money within the United States; or whoever fraudulently possesses, passes, utters, publishes, or sells, or attempts to pass, utter, publish, or sell, or brings into the United States, any such coin, knowing the same to be altered, defaced, mutilated, impaired, diminished, falsified, scaled or lightened – shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than five years, or both.

That seems pretty straightforward and similar to Australian law and I expect every other nation’s law. So who is going to investigate the circumstances that led to the dollar bill below being mutilated?

The graphic appeared in an article this article which was published by the American Enterprise Institute. We are lucky to have organisations like this in the world defending free enterprise and all the benefits that go with it!

Anyway, according to the article the image was “by Darren Wamboldt/Bergman Group”. Here are his details and he can be interviewed at 4880 Sadler Road, Suite 220, Glen Allen, VA 23060.

Its probably a case for the FBI so I hope they appreciate my detective work, which will allow them to spend more time tracking down the corporate criminals on Wall Street who helped create this mess.

I guess they will claim photoshop did it!

So what did the article “How Likely Is Hyperinflation?” written by Peter Bernholz (December 15, 2009) say? Well I told you it was going to be a hard road. This is written by an emeritus professor (meaning he’s retired) from Basel University, Switzerland. The bio attached to the article says his work focuses among other things on monetary economics yet if you read the article he hasn’t yet learned to differentiate convertible from non-convertible currency systems as a first step.

Bernholz confronts us with a supposedly deep and meaningful question from the outset: “Have central bank and government reactions to the crisis created a large danger for the future?”

Then he gets down to business:

During the past several months, concerns have risen that the expansionary policies of the U.S. government and the Federal Reserve System to counter the present crisis are creating the danger of a substantial future inflation. Some speak even of a hyperinflation, that is, of a rate of inflation exceeding 50 percent per month. People believing in the latter scenario base their concerns on results I presented in Monetary Regimes and Inflation: History, Economic and Political Relationships, which shows that all hyperinflations were caused by huge government deficits.

Yes and in the well-known cases in the last 100 years by prior and massive contractions in the supply capacity of the economy. Any spending growth would have created hyperinflation in that context.

But where is the massive supply collapse in productive capacity in the US at present? There are certainly many idle resources and despite some lost manufacturing capacity that will probably not see the light of day again I don’t sense that potential GDP has fallen by any dramatic amount.

Bernholtz certainly provides no intelligence to suggest that it has. Nor in his work does he acknowledge that.

Anyway he thinks there is a hyperinflation coming. He says:

… let me state two facts which in my view cannot be denied: First, that the present crisis has been initiated by the Federal Reserve’s too expansionary monetary policies after the bursting of the New Economy Bubble. Second, that the Fed and the U.S. government embarked on even more expansionary policies to fight the present crisis; indeed, their policies constitute an experiment on a scale which has never been seen before in the history of fighting crises.

These are not facts and there are no one who actually understands what went on would agree with his first “fact”. I explain that in detail in the blog – Monetary policy was not to blame.

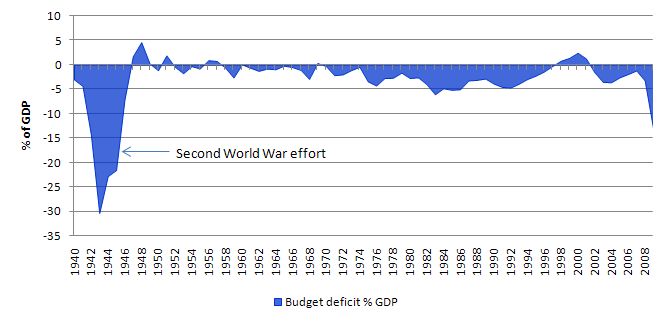

The second “fact” is also untrue. Just the most simple graph from 1940 until the end of 2009 for the US will tell you that the current deficit to GDP ratio (as if it matters anyway) has been “bettered”. The current situation is tame relative to the government net spending as a proportion of GDP during the war years. Further, during those years productive capacity shrank as efforts were diverted to prosecute the war.

In terms of monetary policy, while the Federal Reserve funds rate is currently at at the lowest rates since data is available (1954) there have been several times since then that the rate has gone below 1 per cent (Source). But with demand for credit now very low it is hard to make a case that the interest rates are driving any large move in aggregate demand.

I suppose he will say bank reserves are also at historical highs. That is true but so what? I wrote several thousand words about that yesterday – The complacent students sit and listen to some of that. Banks don’t lend reserves.

Anyway, one of the hallmarks of conservative (free enterprise) attacks on government policy intervention is that they try to seduce the reader/viewer/listener with alleged facts that turn out to be lies. But the uninformed recipient of the information is easily lulled and that is what these characters prey on.

Let me turn to the first point. In a mistaken fear of deflation, the Fed lowered its interest rate to 1 percent and increased the monetary base by about 39 percent from 2000 to 2006 after the bursting of the New Economy Bubble. In doing so it encouraged an incredible credit expansion by the financial sector and thus allowed the subsequent asset bubble. Later, it helped to pierce the bubble by raising its interest rate step by step above 5 percent and by strongly reducing the growth of the monetary base. Though the Fed thus initiated the crisis, we should not forget that it would never have taken such a dramatic course, which hurt the real economy, were there not other well-known defects in the financial system such as:

Interestingly he then lists a number of “market failures” where private enterprise institutions (for example, banks, rating agencies etc), seeking to escape the yolk of government control gamed the system for their own short-term advantage. He doesn’t say it but we know a significant part of this gaming was also criminal.

He also notes that the regulative structure was compromised. Yes, and the American Enterprise Institute gave the neo-liberals succour to demolish state oversight of the market system.

He then says that:

… crises cannot be prevented in a decentralized and innovative market economy. It may be possible to mitigate them by adequate reforms or even to prevent one or the other. But that is the best result one can hope for.

I largely agree with that statement in the sense that private spending is fluky and driven by sentiment in a highly uncertain world. Notwithstanding the perverse incentives that were operating in the financial markets as a result of lax regulative oversight – and it was this that allowed widespread criminal behaviour to run riot – private spending does fluctuate and that is why we should always have in place public policies that can take up the spending slack very quickly.

Using employment buffers (that is, a Job Guarantee) is one example of an automatic stabiliser that would immediately soak up unemployment arising private spending failure from should the unemployed desire a job. There are other policies that can more or less turn on public spending immediately if government cares to have foresight.

But this particular crisis began in the financial markets and then spread into the real economy. With appropriate design of the banking system and the banning of many types of financial transactions the prospect of damaging financial instability can be virtually eliminated which means any crisis would have to originate within the real sector and they are easier to deal with in a policy sense. For Please read my blogs – Operational design arising from modern monetary theory and Asset bubbles and the conduct of banks – for more discussion on this point.

Bernholz then cites evidence spanning the period 1720 to 1975 to prove crises occur regularly. This period of-course spans different monetary systems (convertible and non-convertible) and as such does not comprise a continuous history. We will return to this.

So then we get to the nub – the “Danger of Hyperinflation”.

He asks:

But were these measures not justified because of the dramatic situation and the dangers threatening in the crisis? It is difficult to form a judgement because of the extraordinary extent of the measures and because we do not know the further course of the crisis … But even if all the measures may help mitigate and shorten the crisis, which is probable, it has to be asked whether lowering interest rates and expanding the monetary base – measures similar to those which have already initiated the present crisis – will not bring about even worse developments in the future.

We know that the policy expansion in the almost every country has, in fact, been less than was required to meet the plunge in private spending. How? Because unemployment has risen dramatically.

So while the future course in yet to be seen, we can be sure that the situation would have been significantly worse than it already is if the interventions had not occured. The Great Depression lasted a decade after all because the authorities failed to take the sort of action that we have seen in the recent period.

While I defend the policy interventions I would agree with those who argue that the design (composition) of spending and the over-emphasis on quantitative easing was less than satisfactory.

But in saying that I am not suggesting that the residual of the errant components of the interventions are “dangerous”.

Even Bernholz acknowledges that central bankers around the world are not concerned that bank reserves have expanded so significantly. But his claim is that the central bankers will be coerced by “political and psychological pressures” not to fight the inflation that will emerge from the excessive reserve build up because “unemployment may still be rising” and it wouldn’t look good.

The missing link in his story is an explanation of what will drive this demand-pull inflation (as opposed to a cost-push inflation origin where stagflation can easily occur if policy settings are poorly handled).

If, as he notes, unemployment is rising then we know that output growth is insufficient to soak up the new entrants into the labour market and the existing pool of jobless.

Wages growth will remain flat. Mark-up push will be discouraged by the very soft product markets. So where are the inflationary impulses going to come from?

In this regard, there was a very interesting article in this week’s Economist Magazine (January 14, 2010) – entitled The trap: The curse of long-term unemployment will bedevil the economy – which considered the fact that the US labour market is now in a “dismal” state.

The Article said:

THE 2000s … turned out to be jobless. Only about 400,000 more Americans were employed in December 2009 than in December 1999, while the population grew by nearly 30m. This dismal rate of job creation raises the distinct possibility that America’s recovery from the latest recession may also be jobless. The economy almost certainly expanded during the second half of 2009, but 800,000 additional jobs were lost all the same.

They note that after the 2001 US recession, “wages stagnated even as the cost of living rose, forcing households to borrow to maintain their standard of living.”

So far from it being a monetary policy issue, this account places the origins of the crisis squarely in the distributional system. But we also have to step back and understand that the 2001 US recession was a direct product of the Clinton surpluses which dragged the economy down and promoted the incentives for workers to increase their borrowing to maintain their consumption levels.

At the same time the neo-liberal onslaught in the US saw Clinton then Bush relax oversight in the financial markets and unleash the financial engineers onto the population – that debt spiral followed. I cover that issue in these blogs – Some myths about modern monetary theory and its developers – The origins of the economic crisis.

The Economist says that:

Of paramount concern is the growth in long-term unemployment … [which is at] … the highest rate since this particular record began, in 1948 … Just as troubling is a drop of 1.5m in the civilian labour force (which excludes unemployed workers who have stopped looking for work). That is unprecedented in the post-war period. If those who have stopped looking were counted, the unemployment rate would be much higher. These discouraged workers represent a reservoir of labour-market slack that will dry up only with strong economic growth.

Are you getting the impression that this is an economy that has run out of resources and any extra demand will hyperinflate the place?

They also suggest that where employment growth did occur in the last decade (retail and in entertainment) it was “largely supported by household borrowing”. On this they conclude that:

Not only is a new wave of borrowing unlikely to develop after the recession, but household deleveraging is nowhere near complete, according to a new McKinsey study (see article). Having spent beyond their means in the previous decade, Americans will now need to spend beneath their means in order to reduce their debt burdens. That will place a strong constraint on job growth in those cyclical sectors.

They also realise that with these substantial deflationary forces prominent “the weak labour market will continue to keep wage levels in check”.

There are more than six unemployed Americans for every job opening, and competition for job openings is getting more intense, not less, despite the resumption of growth … [this will] … allow companies to underpay well-qualified workers. Real earnings declined last year and are unlikely to experience rapid growth soon … Without job growth, household indebtedness will linger as a problem, depressing spending and hiring. Joblessness is a trap the American labour force may not soon escape.

Does that sound like an economy that is in need of less spending rather than more? Does that sound like an economy that is entering an inflation gap (where nominal demand outstrips real supply capacity)?

And if it sounds like an economy that desperately needs more nominal spending growth and the private sector prospects are so anaemic then where else is the demand support going to come from? You guessed – on-going budget deficits.

But Bernholz seems to think otherwise. But if you read his argument you will start to relate to the title of the blog.

He says that we are about to pay the price for the current expansionary policies:

To understand the underlying problems we have to remember a mostly forgotten important function of financial institutions in a decentralized market economy. In such a system it is one of their tasks to coordinate the savings of consumers (including obligatory ones for health and unemployment insurance) with the net investment of non-financial business firms and governments. In real terms this corresponds to a reallocation of factors of production from producing consumer goods to the production of means of production with the consequence that more and new goods can be produced in the future. Savings by consumers transferred as additional means to producers lead to a reduction in the demand for consumption goods and allow productive firms to increase their investments.

It amazes me that when these characters get stuck – amidst all the empirical rejection of their notions (as above) – they resort back to their old discredited theories for comfort – this time it is back to loanable funds doctrine.

The idea that investment is in some way contained by the amount of savings available in the economy at any point in time and that the interest rate mediates the demand for funds (investment) and the supply of funds (saving) is not descriptive of our monetary system.

Credit is endogenously created by banks as they make loans (and deposits) as credit-worthy customers make applications. Loans create deposits in a modern monetary economy. Investment is not constrained by the saving patterns of consumers in this sense.

As investment spending occurs national income increases and generates extra saving (if households desire to consume less than they earn overall). So investment brings forth its own saving – not the other way around. Please read my blog – Studying macroeconomics – an exercise in deception – for more discussion on this point.

If that wasn’t enough, Bernolz then continues with the old line:

In this process the real interest rate is determined by the impatience to consume and the greater productivity of more roundabout production processes (or expressed otherwise, the marginal productivity of real capital).

Sorry, the real interest rate is determined by the nominal interest which is set by the central bank and the current inflation rate which depends on a lot of factors.

At the macroeconomic level (which is the level of analysis he is conducting), interest rates are not determined by the interplay of saving (the residual after consumption decisions have been made) and investment. Interest rates are a nominal aggregate in the sense that Keynes described them.

Further, and this is not a topic I will expand on is this blog – the concept of a “marginal productivity of real capital” is fundamentally flawed and was fatally discredited during the famous capital debates (Cambridge controversies) in the 1960s (but in reality the insights trace back to 1926 when Pierro Sraffa released is beautiful attack on mainstream price theory. I will write a separate blog on this topic one day but the “take away” at this point is that there is no marginal product of capital that can be defined prior to knowing the rate of profit (interest) and so the former cannot generate the latter – which is a major violation of the theory Bernolz is rattling out at this point of his argument.

As an aside, the mainstream economists chose to stay silent after these debates (Samuelson famously conceded defeat on behalf of the orthodoxy) and after some time went on preaching marginal productivity theory and its distributional implications as if nothing had happened.

That is the method they always use – ignore the evidence, the logical inconsistencies, the anomalies – and continue as before – after all the students will hardly ever know any better.

So in similar (dishonest) mode, Bernholz continues, as if there never had been debates like this:

The resulting “natural” real rate of interest can change to a minor degree, but should, judging from the non-inflationary environment of the gold standard in developed countries before 1914, be around 3 to 4 percent. This means that if central banks lower the nominal rate of interest below the natural rate, they send the wrong signal to producers, including builders and purchasers of houses. They are motivated to indebt themselves to initiate additional investments and to enter production processes which would be unprofitable at interest rates from 3 to 4 percent. Consequently, not all of these investment decisions can be executed since not enough real factors of production are put at their disposal by the real savings of households.

The natural rate of interest has always been an ideological construct that has defied measurement. Please read my blog – The natural rate of interest is zero! – for more discussion on this point.

So we are making assessments about the situation today – in a fiat monetary system with non-convertible currencies and flexible exchange rates with the situation that may have occurred during a gold standard? Its a hard road.

First, even those that believe in this sort of stuff acknowledge that structural changes can occur which changes the “neutral interest rate” which is the modern variant of the old natural rate idea. So in Australia at present the central bank has suggested its neutral rate is now much lower than it was because the commercial banks have broken out of the stable pattern of setting mortgage rates proportional with the policy rate.

Second, capital formation (investment) is driven by complex calculations that firms make about the returns on the capacity developed and the cost of developing it with some allowance for the future course of inflation. All this is very uncertain. It is possible that lower nominal interest rates encourage more people to borrow because the “costs” of the projects relative to their expected returns fall. But it is not straightforward.

Further extrapolating that to the macroeconomic level if fraught with fallacy of composition type problems. Not every “spender” is advantaged by reductions in nominal interest rates. Those on fixed incomes typically are disadvantaged. So the net spending effect is very uncertain at the macro level.

Third, once again he is trapped in his nonsensical loanable funds reasoning. Investment is not constrained by the nominal or real saving of households. Investment provides the income growth to help households save is the better way of thinking about it. Investment is contrained by expectations of future revenue flows and the costs of acquiring funds.

Of-course, to be non-inflationary, investment spending has to be able to expand productive capacity using available real resources – labour, materials etc. Clearly, in a closed economy, if consumers fully occupy all available resources then there can be no investment. A basic condition (that Marx identified) is that there has to be a surplus produced in the consumption (wage) goods sector – that is, workers who produce consumption goods like food etc cannot consume all those goods. Otherwise, there would be no consumption goods available for the workers in the capital goods sector.

But as soon as you open up the economy, these constraints become significantly different and more complex. Then investment can clearly be above saving by drawing on real resources from elsewhere.

Bernholz then demonstrates he doesn’t understand this logic:

In real terms, net investment must always equal savings. As a consequence, there remain only two ways to bring this equality about if nominal interest rates are too low and are disturbing this relationship. Either the central bank increases interest rates again – in this case, the net investments initiated are no longer profitable and have to be interrupted, as happened with the housing crisis in the United States – or the central bank leaves interest rates at their too low level, resulting in inflationary developments that cannot be avoided.

It is incorrect to say that “net investment must always equal savings”. That will only hold in a closed economy with no government sector. The true statement is that the following sectoral balance will always hold – leakages (Saving + Taxes + Imports) will equal injections (Investment + Government spending + exports). That is a fundamentally different proposition to that which Bernholz is propagating.

As a consequence the rest of his policy discussion is inapplicable.

He then claims that the build-up of bank reserves presents a huge dilemma for the central banks, which is also “increased by the fact that high budget deficits of governments have to be financed”.

So what is this dilemma?:

If expectations of households and firms become positive, another sizable asset bubble has to be expected because of the vast liquidity created. And inflation will follow the bubble if the Fed does not act speedily and strongly to reduce the monetary base and to increase the interest rate to normal levels. But such a policy may lead to another crisis and recession. On the other hand, if the Fed does act too late and not strongly enough, inflation cannot be prevented.

Please read yesterday’s blog – The complacent students sit and listen to some of that – for a very long discussion of why the “vast liquidity” hypothesis is fatally flawed.

There are no inflation threats from the current level of bank reserves. There may be inflationary fears if investors get very optimistic and banks start lending out willy nilly and nominal demand booms out of all proportion to real capacity in the economy. That might happen – but we are so far from that situation at present that it is not even worth considering.

Further, bubbles in specific asset classes (particularly housing) are always possible but they do not constitute what we call inflation (a generalised and continuous acceleration in all prices).

The large money base will not influence either possibilities. Banks have no greater or lesser capacity to lend as a consequence of the reserve buildup.

After leading us along to think of that hyperinflation might be lurking, Bernholz tells us in closing that he even though budget deficits are high in the US at present, the increased borrowing from capital markets is attenuating their impact on the monetary base.

What he is saying without saying it is that the debt-issuance associated with the deficits drains the bank reserves and reduces the monetary base by definition. That is a fundamental operation that central banks use to ensure their target interest rates are met.

But we always have to remember that this is all a “wash” – the government is just borrowing back the funds it created in the non-government sector anyway. Further, it is true that the non-government sector could spend more if they didn’t buy the bonds. But then the deficit would go down anyway.

But of-course, we are also warned in closing that the “incredibly huge holdings of dollar assets are owned especially by the central banks of China, India, and the Gulf States – may pose other and later dangers” … so don’t sleep soundly tonight folks the danger is still there.

Although at my place … there will be plenty of easy sleeping going on!

Nice article Bill.

I’d like to see these Say’s Law worshiping bastards like Peter Bernholz hanging from their Adam Smith ties.

Why is it all of these “money supply” commentators continually fail to look at the destruction in private money supply? If the two are netted, we are experiencing a significant reduction in the money supply. The increased spending by the government does not offset the reduction in private spending.

The other point that these commentators fail to appreciate is the need to play hard ball with the financial interests to keep them in line. A government job guarantee is one of the best ways to insulate the public from private banker folly – yes, it is controversial for conventional thinkers but it is also playing hard ball.

The “hyperinflation” themes just play into the hands of financial interests they purport to criticize.

Considering we have very powerful interests that tend to get what they want, you have to wonder to what extent the current situation is satisfactory to them – they were responsible for the huge increase in financial speculation, now they want to design the restructuring taking place at the expense of those who had little control of the situation. At least their ethics are consistent.

Considering the widespread criminal activity that occurred during the crisis, it should be obvious how to characterize anyone advocating policies strengthening those players’ position.

Bernholz pretty clearly states that he doesn’t think it’s likely that hyperinflation is coming to the US –

Bernholz: “But does this mean that inflation may evolve into a hyperinflation in the United States? I believe not.”

“The missing link in his story is an explanation of what will drive this demand-pull inflation (as opposed to a cost-push inflation origin where stagflation can easily occur if policy settings are poorly handled).”

Just to check that I am understanding correctly… By this, you mean that there could plausibly be some inflation via something that pushes costs up (e.g. rising oil prices), but not because excess demand is pushing prices higher – something that should not happen when there is high unemployment and a massive shortfall of aggregate demand, such as we have now? Does this imply that cost-push stagflation is possible, but demand-push stagflation should generally be impossible?

On that note, could you do a “debriefing” some time on stagflation? That seems to be one of the neoliberal “trump cards,” where they can say “but how do you explain this?” I don’t think I really understand it from a MMT perspective.

Very informative blog.

“And it’s a hard road till I die”

Dear Bill – depends upon how determined we are to enjoy each day, regardless of ‘the world’.

Am not defending neoclassical concepts but I do believe it is always necessary to remember the true worth and dignity of each human being: just because I don’t know how to fly a 747 does not demean me in any way; just because neoclassical intellection does not know how to fly an economy does not demean people (under the illusion of these concepts) in any way that I know of. There are so many conceptual (human) worlds on this planet that defy gravity and common sense. Clarity is the hard road if there is one, broadening one’s view: – but then that is why a human being is made a door to fulfillment. Am sure that is why you play music and beat the drum of MMT! However greed certainly demeans a human being (all the way back to the animal core) – but then greed only occurs in the vacuum of honesty and generosity. Arrogance spirals into the vacuum of ignorance – what can you do but pay absolutely no attention!

I really do enjoy this blog!

Cheers …

Gamma,

The very fact that Bernholtz would even resort to mentioning hyper-inflation is proof enough the blokes a complete goose.

cheers.

@ Matta

Energy is the Achilles heel of the modern economy, being the sine qua non. The MMT of energy economics is ERoEI (energy returned on energy invested). Basically, the declining ratio is forcing out hand, and yet the US doesn’t have a coherent energy policy to address the developing challenge.

Increasing energy cost owing to externalities like pollution and climate change, as well as resource depletion and decline in resource quality, translates into increased cost of production, resulting in a broad price pressure. This can happen through physical constraints and also through markets, as in the early 70’s when the OPEC cartel raised petroleum prices (at the time when Bretton Woods II collapsed and the world was adopting a non-convertible flexible rate monetary regime). This resulted in an international oil shock (1973-1974), a “supply shock” whose consequence was economic contraction due to higher energy cost, along with broad cost-push price pressure. The US recently experienced a mini-oil shock when petroleum rose to $147 a barrel since it is a maintenance expenditure that cannot be foregone and is difficult to reduce substantially without disruption of the status quo. This was a factor in precipitating the present crisis.

Like money, energy is fundamental to developed economies. This is an emerging challenge that has been interrupted by the economic contraction. Stay tuned.

E R O E I …what does it mean?

A Net Energy Parable: Why is ERoEI Important?

An EROEI Review