Today (January 22, 2026), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the latest labour force…

More calls for job creation … but then

In the last few days I have seen more calls from commentators for policy makers to take new initiatives to generate jobs and growth. Some of these calls have come from commentators and research centres that sit on the “progressive” side of the macroeconomic debate. Unfortunately, their proposals are always compromised by their demonstrated lack of understanding of how the monetary system operates. In my view these proposals actually undermine the need to advance an understanding that sovereign governments can create true full employment and should do so as a matter of urgency. By playing ball with the conservatives and choosing to focus on deficit outcomes these progressives divert the policy focus away from the real issues. In short, the federal budget deficit outcome should never be the focus of policy.

For example, William Pesek’s Bloomberg column (November 30, 2009) tackling the deflationary situation emerging in Japan as the Yen appreciates (in the face of a falling US dollar) was interesting. He notes that even though Japan is growing again (4.8 per cent in the September quarter), the economy shrank on an annualised basis by 4.5 per cent with exports plummeting by 23.3 per cent in October alone.

He notes that the Japanese government is in somewhat of a position as to what to do next given the deflationary forces that are building up. The standard fiscal response has been to “pour untold trillions of yen into public works projects that produced an army of white elephants. Other than unneeded dams, bridges and a public debt nearly twice the size of its $4.9 trillion economy, Japan has little to show for it.”

While we can debate the veracity of that claim his next statement is what interested me.

He said:

It’s time for the government to meet the BOJ halfway. The key isn’t just being bold, but trying something different. Yukio Hatoyama’s Democratic Party of Japan, in power since September, is tweaking policies to give more financial support to households …

… A look in the mirror would help. It’s bizarre, for example, that Japanese officialdom is focused on raising consumption taxes to pay off debt. The reason for all that debt is a lack of consumer demand. In what alternative universe do they think higher taxes will reverse things?

Let’s try lower taxes instead. Supply-side economics is a dubious thing, but it’s time Japan encouraged small businesses to create new jobs, boost productivity and raise incomes.

Why do the same things over and over again when they aren’t working? Here … [local banker] … suggests a money-funded tax cut. The government would send households a check, issue debt to fund it and ask the BOJ to buy it and hold it in perpetuity.

That might be too radical for some in Tokyo. Yet we need a clean break with the discredited policies of the past. All the concrete Japan pours into rural areas is merely a Band Aid at a time when competitiveness is hemorrhaging amid China’s rise.

So he is suggesting that link between net government spending and public debt issuance be broken. I think that should have been done a long time ago. Given that the Japanese government is not revenue constrained there is no need for it to issue debt especially when it is running a zero interest rate policy and can leave the deficits sitting in commercial bank reserves.

What form the increased net spending takes (whether it be increased infrastructure spending, tax cuts or whatever) is then debatable. Japan needs a national superannuation scheme in my view to reduce the need for individual saving. That would be a good place to start.

The other good place to start would be an employment guarantee although I suspect this would be a difficult cultural ask for the Japanese. More work is needed on that.

You also see this call for something different in Paul Krugman’s November 29, 2009 column – The Jobs Imperative.

He is now advocating that job creation should become the focus of US fiscal policy. What took him so long?

Krugman says that:

If you’re looking for a job right now, your prospects are terrible. There are six times as many Americans seeking work as there are job openings, and the average duration of unemployment – the time the average job-seeker has spent looking for work – is more than six months, the highest level since the 1930s.

These average durations are actually modest compared to those in Australia and Europe but that doesn’t detract from the gravity of the situation in the US.

I agree with Krugman that with the financial system now unlikely to collapse (compared to 18 months ago) the major debate is focusing on cutting back the stimulus packages and even pushing interest rates up – note that the central bank in Australia once again hiked rates – its third increase in as many months even though we have 13 per cent labour underutilisation rates.

Right-wing so-called experts like ANU professor of economics Warwick McKibbin (who is also a RBA board member) said that interest rates across the world have to rise because we are on the precipice of a renewed price bubble. I am not sure where he has been looking but in a way his reactions are puppet-like whenever the press put a microphone in front of him. Too much public debt – too bigger deficits, too lower interest rates … straight from some second-year macroeconomics text book that totally misrepresents the operations of the monetary system

I see Dubai collapsing, Japan deflating, the UK still mired in recession, stagnant growth everywhere, and high rates of labour underutilisation everywhere.

The point Krugam makes is sound:

… all the urgency seems to have vanished from policy discussion, replaced by a strange passivity. There’s a pervasive sense in Washington that nothing more can or should be done, that we should just wait for the economic recovery to trickle down to workers. This is wrong and unacceptable.

You don’t hear that from the McKibbon’s of this world. But then they have safe and very well-paid jobs and are largely immune from the negative impacts of the recession.

Is it harder to get a job in the US than to lose one?

This question can be answered fairly clearly by examining the Gross labour flows that are available from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

To fully understand the way gross flows are assembled and the transition probabilities calculated you might like to read this blog – What can the gross flows tell us?..

As a refresher, gross flows analysis allows us to trace flows of workers between different labour market states (employment; unemployment; and non-participation) between months. So we can see the size of the flows in and out of the labour force more easily and into the respective labour force states (employment and unemployment).

The various inflows and outflows between the labour force categories are expressed in terms of numbers of persons. But a useful alternative presentation is to compute transition probabilities, which are the probabilities that transitions (changes of state) occur. For example, what is the probability that a person who is unemployed now will enter employment next period.

So if a transition probability for the shift between employment to unemployment is 0.05, we say that a worker who is currently employed has a 5 per cent chance of becoming unemployed in the next month. If this probability fell to 0.01 then we would say that the labour market is improving (only a 1 per cent chance of making this transition).

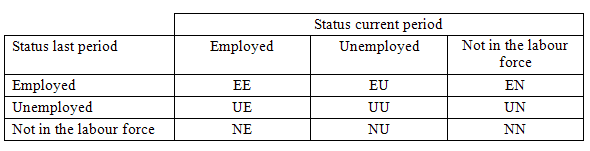

The following table shows the schematic way in which gross flows data is arranged each month – sometimes called a Gross Flows Matrix. For example, the element EE tells you how many people who were in employment in the previous month remain in employment in the current month. Similarly the element EU tells you how many people who were in employment in the previous month are now unemployed in the current month. And so on. This allows you to trace all inflows and outflows from a given state during the month in question.

The transition probabilities are computed by dividing the flow element in the matrix by the initial state. For example, if you want the probability of a worker remaining unemployed between the two months you would divide the flow (U to U) by the initial stock of unemployment. If you wanted to compute the probability that a worker would make the transition from employment to unemployment you would divide the flow (EU) by the initial stock of employment. And so on. So for the 3 Labour Force states we can compute 9 transition probabilities reflecting the inflows and outflows from each of the combinations.

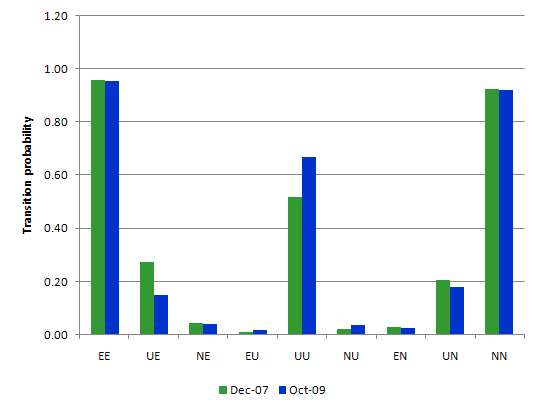

The first graph compares the US transition probabilities as at December 2007 with October 2009 (see the accompanying Table for values). The data is from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

There has been only a slight decline in EE over the downturn. The UE probability, however has dramatically shrunk reflecting the drying up of vacancies. The EU probability has increased but the EN has decreased which means that workers who lose their jobs are more likely to remain unemployed than leave the labour force.

The other interesting result is the significant rise in NU and the fall in NE. Together they mean that new entrants to the labour force are now increasingly likely to become unemployed than employed. Similarly, less unemployed workers are now leaving the labour force.

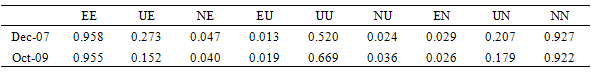

The next graph shows time series of the various probabilities since December 2007 to October 2009. We have already seen it is now harder to get a job in the US for the unemployed and new entrants.

The 4 time-series graphs tracks the downturn period. The top left-hand graph shows the same state transitions (EE, UU, NN) and while the EE and NN transitions are fairly steady, the UU (the probability of remaining unemployed) has risen substantially.

Further, the bottom left-hand graph shows the transitions between employment and unemployment. UE continues to decline while there is some evidence that EU (probability of a loss of job into unemployment) is levelling-out. The top right-hand graph shows the transitions between Non-participation and unemployment and confirms our earlier point that new entrents are more likely to enter the labour force as unemployed rather than employed (see NE on lower right-hand graph).

So it is clear that it is now signicantly harder to get a job in the US even with modest growth returning.

Need for a jobs plan

Within this context, Krugman is now arguing that while:

… the recession is probably over in a technical sense, but that doesn’t mean that full employment is just around the corner … it’s usually years before unemployment declines to anything like normal levels.

And the damage from sustained high unemployment will last much longer. The long-term unemployed can lose their skills, and even when the economy recovers they tend to have difficulty finding a job, because they’re regarded as poor risks by potential employers. Meanwhile, students who graduate into a poor labor market start their careers at a huge disadvantage – and pay a price in lower earnings for their whole working lives. Failure to act on unemployment isn’t just cruel, it’s short-sighted.

So it’s time for an emergency jobs program.

Hallelujah! This is the point that the so-called experts who are calling for cut-backs always ignore. The huge costs of the aftermath of a recession. It beggars belief really. The daily loss of GDP and the permanently damaged lives that arise from leaving unemployed (and underemployment) at high levels for very long periods of time are huge and dwarf all other economic costs (arising from so-called microeconomic inefficiencies).

The problem is that Krugman is also not fully confident in his own logic. He prefers to advocate academic matters in terms of what he calls “a matter of political reality” which translates into conceding that the deficit-terrorists are winning the battle and so a “somewhat cheaper program that generates more jobs for the buck” is needed.

The point I am making here is that I think the role of the academic is not to play politically cute games. There are enough politicians who are doing that. Academics have to outline proposals that arise from a thorough understanding of the way the monetary system operates and then push those ideas into the policy realm.

After all, we are not standing for office and most politicians are not qualified to really understand the research.

Krugman rejects indirect measures to create jobs – like tax cuts. I do too.

He is correct in saying:

Meanwhile, the federal government could provide jobs by … providing jobs. It’s time for at least a small-scale version of the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration, one that would offer relatively low-paying (but much better than nothing) public-service employment. There would be accusations that the government was creating make-work jobs, but the W.P.A. left many solid achievements in its wake. And the key point is that direct public employment can create a lot of jobs at relatively low cost.

I agree but would argue that the US and most other economies need a full blown version of the WPA. A good place to start would be a Job Guarantee which would be an unconditional job offer to anyone who wanted to work at the federal minimum wage (properly determined to be a living wage).

I do not support partial schemes that are driven by fear that the deficit-terrorists will baulk.

In this context, I was interested in yesterday’s release of a jobs plan by the Washington-based (progressive) Economic Policy Institute.

As an aside, I am always bemused when some “progessive” or otherwise so-called think tank comes up with a “bold new plan” that is modest in its reach and fails entirely to recognise that there has been substantial research and policy design by modern monetary theorists on the design and operation of employment creation plans.

Do these people reject our broader employment guarantee proposals? If so, why don’t they at least engage with them rather than holding out that they are proposing something that hasn’t been really examined in any detail before?

These “new bold plans” are in fact pale attempts at addressing the problem. For example, I consider that the EPI’s American Jobs Plan, which aims to create at least 4.6 million jobs in one year, fits into the league – no recognition of past work by progressive economists who have been pushing these issues for years.

Anyway, who would get the 4.6 million jobs?

On page 15, the EPI say that:

Jobs would be made available broadly to the unemployed, but local governments would be permitted to target the program to those most in need, such as those unemployed for more than six months or people residing in a high poverty community.

The US Bureau of Labor Statistics provides the following breakdown of unemployment (thousands) by duration for October 2009:

- Less than 5 weeks – 3,147

- 5 to 14 weeks – 3,717

- 15 weeks and over – 8,834

- 15 to 26 weeks – 3,240

- 27 weeks and over – 5,594

So the scheme will not even provide enough jobs for those who have currently been unemployed for 27 weeks or over and the flows into that pool will expand over the course of the program.

If you read the EPI report you understand how costly and damaging unemployment is. If that is so, then why – especially if you claim to be a progressive think tank (to quote Krugman) – limit your policy response to 4.6 million jobs when you have 24.5 million unemployed?

Krugman wants us to get back to full employment. Then why advocate partial plans like this.

So why? Well you can guess why. They are scared to bejesus of the deficit impact.

On page 18 of the EPI report where they examine “how the US would pay for the scheme” we read that:

When unemployment moderates and the economy has rebounded, it will be appropriate to address the federal budget deficit. The spending required by the American Jobs Plan would occur within the first two years after its enactment; in years three through 10, all of this spending could be recouped through a financial transactions tax.

The terminology – “appropriate to address the federal budget deficit” – gives the game away. As if it is a policy target in itself. MMT tells you that the dollar deficit outcome or the deficit as a percentage of GDP or as some index relative to Mount Everest – whatever – these calibrations should never be a focus of macroeconmic policy.

What the government has to focus on and measure accurately is the real state of the economy and the rate of growth of nominal demand relative to real capacity.

The progressive goal should be always to advocate and create full employment. That is the position that maximises material welfare. Whatever deficit that is associated with that level of output is what it will take. That deficit outcome is neither big nor small – it is the appropriate fiscal injection.

Under some circumstances that “appropriate” budget outcome could be a surplus (for example, when there is a strong net export contribution to GDP growth). But these situations will be rare.

Further, why is the EPI advocating budget neutral outcomes for the scheme between years 3 and 10? What is the basis for that suggestion? I suspect it just reflects fiscal conservation which is just another own-goal for the progressives. In doing so, they become part of the problem.

The EPI is also advocating a tax credit along the lines proposed by the CEPR – Please read my blog – The enemies from within – for a critique of this idea.

You might also want to read the ILO Jobs Pact which is largely sound but doesn’t emphasise direct job creation enough and when it does suggests they should be temporary schemes only. I fundamentally disagree with that because I know from dealing with the ILO directly that it is based largely on a deficit-dove view of the world. They also struggle with an appreciation of MMT.

Conclusion

In the blog – The enemies from within – I argued that progressive positions that accept the constraints put on policy by the fiscal conservatives, who fail to understand how the modern monetary system operates are doing that side of the debate a dis-service and really undermining the prospects for the supposed target groups (the most disadvantaged citizens among us).

I think that these responses are probably more damaging for the creation of the true full employment and equity than those which come from the so-called right. But then when it comes down to it, the deficit-dove progressives are hard to distinguish from the right.

hi bill,

rba raises interest rates by 25 basis points. westpac raises rates by 45 basis points

would like to get your take on this. have funding costs gone up , or is it pure greed

given the government deficit position ,as an interested amature i would like to get an understanding of the cost of funds for banks at the moment. and their pricing stratergy. does it have to do with ratio of borrowed and non borrowed reserves.

according to mmt deficits should put downward pressure on interest rates despite the arbitary nature of pricing by the rba. so why is westpac raising above the rba increase.

perhaps it might be worthy of a post by you on this,

Hi,

I have three comments/questions (for anyone, I know Bill is busier than usual):

1. This BIS working paper especially pages 16 onward (“Are bank reserves special?”) seems on my cursory reading to mostly reflect reality as described by a subset of MMT. I wonder if Mark Thoma (for example) would pay it more attention than he did Bill.

2. Bill said “Japan needs a national superannuation scheme in my view to reduce the need for individual saving.”

Isn’t the problem more with the high savings desire of businesses (i.e., the domestic private sector excluding households)? The household savings rate has been in a steady decline from 18% in 1981 to 2.2% in 2007 despite high government deficits. Perhaps it has risen in the crisis but unfortunately official data isn’t out yet (AFAIK).

3. Bill said “Under some circumstances that “appropriate” budget outcome could be a surplus (for example, when there is a strong net export contribution to GDP growth). But these situations will be rare.”

Could one such situation be when a country has a large retiree population relative to employed workers? (Japan is a candidate for this at some stage given demographic trends). This seems inherently inflationary (current demand exceeding capacity) but clearly Japan is not there yet (and maybe people will just keep working into their later years to compensate).

^^^^^

The gold standard ended in 1983.

Mahaish,

The RBA sets rates exogenously therefore there is little if any relationship between a governments bugetary position and the interest rate.

The Government / RBA can have any interest rate it chooses regardless of it’s budgetary position.

Dear Alan

The convertible currency system ended in 1971 but some countries including Australia took a little longer (as you note) to go free.

best wishes

bill

Dear Mahaish

The commercial banks are price takers in wholesale lending markets. At present, the margins required on new borrowing are much lower than they were in say January 2009 but they are still higher than the margins on the funds that are currently maturing (and need to be repaid).

But it is without question that the banks are making profits for themselves ahead of providing service to the public. The difference in wholesale margins is nowhere near that which would justify the Westpac move.

best wishes

bill

Dear HBL,

The BIS paper by Borio/Disyatat is pretty good, and particularly so in the areas you highlight. Disyatat did a paper this summer similarly dismissing the money multiplier model. Don’t know what Thoma’s reaction would be, but Borio is highly respected among neoclassical monetary economists as far as I know, so you might make some headway.

As an academic, though, while I am very happy when I see papers of this sort published by neoclassicals as it certainly gives me some hope, it’s always disappointing at the same time that attribution of these of ideas is not given to folks in the MMT, horizontalist, endogneous money, circulation, and other traditions that have been arguing and publishing refereed research for decades in some cases arguing much the same and providing a wealth of theoretical and empirical evidence. Some people call that plagiarism, in fact.

Best,

Scott

Hi Bill,

I’d love to get your take on this if you get a chance:

http://georgewashington2.blogspot.com/2009/12/keynesians-are-wrong-you-can-have.html

Dear Ian

I cover some of these issues in today’s blog. If you have any specific issues you want me to comment on then please let me know.

best wishes

bill

billy, i am going to take the liberty of posting a very long quote from your blog. if you object, please let me know and i will ask to have it removed. thanks for all your work.

selise

http://news.firedoglake.com/2009/12/04/unemployment-numbers-should-not-sap-momentum-for-new-job-creation-spending/

Hi Bill,

I have been attempting to recreate some of the results of your transitional probabilities table in order to give a dynamic view of the current Australian labour market, but I am having a lot of trouble coming to similar results as you mathematically.

For example if the employment flow goes up in this month, when you divide it by the previous month, you get a result such as 1.01 etc. Is there a template for which you used your methods? If so I would really appreciate if you could put me in the right direction.

Also are you planning to analyse the local Australian labour market soon using the transitional probabilities method? This is an extremely interesting topic.

Thanks for your insights!

Anders