These notes will serve as part of a briefing document that I will send off…

Japan’s Government Pension Investment Fund and the yen – mainstream macro myths driving bad policy

With an national election approaching in Japan (February 8, 2026), there has been a lot of discussion about the so-called ‘weak yen’ and whether the Bank of Japan should be intervening to manage the value of the currency on international markets. PM Takaichi has been quoted as saying that the weak yen is good for Japanese exports and has offset some of the negative impacts on key sectors in Japan, including the automobile industry. She also said that the government would aim to encourage an economic structure that could withstand shifts in the currency’s value, largely by encouraging domestic investment. The yen depreciation is another example of the way mainstream economists distort the debate. They argue that the Bank of Japan should be increasing interest rates further to shore up the yen. Previously, they pressured the government into creating a pension fund investment vehicle to speculate in financial markets to ensure the basic pension system doesn’t run out of money. These two things are linked but not in ways that the mainstream public debate construes. It turns out that pension myths, are directly responsible for the evolution of the yen. This blog post explains why.

Yen depreciation

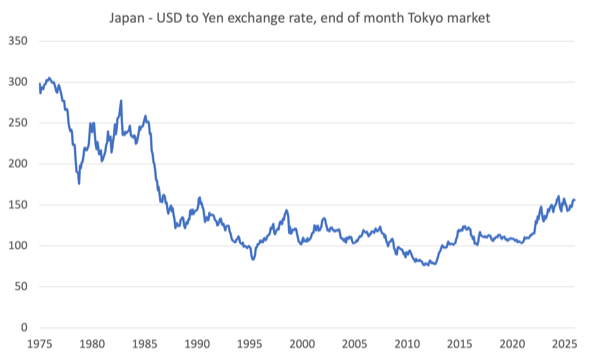

In January 2012, the USD/yen parity stood at 76.3 and by December 2025, the value was 155.9, a depreciation of 104 per cent.

The depreciation in the yen against the US dollar since the early aftermath of the GFC has come in two stages.

First, between January 2012 and July 2015, the yen depreciated by 62.8 per cent.

It then firmed a little (gaining 14.2 per cent in value) before resuming its downward path.

Second, since April 2020, the yen has depreciated by 46.3 per cent.

The following graphic shows the history of this parity since January 1975.

There are winners and losers from the yen’s movements.

Clearly, the exporters (including the tourism industry) gets a boost because all goods and services quoted in yen become cheaper for buyers using foreign currency.

For example, the rising cost-of-living for Japanese households when they go to local supermarkets is not felt as much by tourists who have increased yen purchasing power as a result of the yen depreciation.

That was very apparent when I was working in Japan again last year – it was clear that prices of all food items had risen in our local supermarket but when I did the conversion back into Australian dollars, the shift in purchasing power was hardly noticeable to me.

The Japanese consumers are the losers – all imported goods and services quoted in foreign currencies become more expensive when expressed in yen as a result of the depreciation.

The import price rises have been feeding (somewhat) into the domestic CPI rate of growth and the mainstream obsession with rising interest rates has been stimulated as a result.

The Ministry of Finance has also been telling us that they will ensure that the yen doesn’t depreciate too much – which is code for the Bank of Japan intervening in foreign exchange markets by buying up yen and selling foreign currency holdings.

Mainstream economists and observers have once again seen blue and called it red.

They are interpreting the rising yields on long-term Japanese government bonds and the depreciation in the yen as being evidence that the ‘markets’ (that amorphous collective used in scaremongering narratives) have cast a negative judgement on the fiscal position of the government.

As I noted in my recent blog post – Japan goes to an election accompanied by a very confused economic debate (January 29, 2026) – the rising bond yields have little to do with fiscal policy settings and everything to do with the so-called ‘normalisation’ of monetary policy being conducted by the Bank of Japan at the moment.

It is also apparent that one of the reasons the yen has been depreciating since 2012 has everything to do with confused thinking among fiscal authorities.

Which is what this blog post is about.

The stupidity of neoliberalism

There are countless examples of poor decisions resulting from poor starting assumptions.

For example, think about outsourcing of government services.

1. Government adopts the assumption (driven by massive pressure from vested interests in the private sector) that it can no longer afford to provide delivery of key services within house.

2. Action – outsource to a private contractor.

3. The private contractor needs to make a profit (that the government delivery didn’t need to make) and as a result looks at ways of reducing the scope and quality of the service and/or hiking the price to the end user.

4. Result – quality of service declines, employment is lost, and prices rise.

5. Sometimes – the decline is so catastrophic that the government has to take back control of the delivery.

There are so many examples of this type of sequence since the neoliberal privatisation-oursourcing-userpays madness began in the 1980s.

In the context of this blog post think about government delivery of aged pensions to its population.

As the neoliberal fictions about government financial capacity became dominant, one of the focal points in the policy space became the viability of government pension systems.

The mainstream claim was that governments would not be able to afford to pay pensions as populations age because they would ‘run out of money’.

In 2001, the Japanese government created the – 年金積立金管理運用独立行政法人 (Government Pension Investment Fund) – but it wasn’t until 2006 that its organisation was consolidated into a functioning entity.

It is the ‘largest pool of retirement savings in the world’ (Source) and involves the government as a speculator in financial markets.

Over time it has diversified its investment portfolio through the use of so-called ‘external asset management institutions’ – which are just all the usual suspects (major investment banks and hedge funds).

So some of the investment returns are hived off by these parasitic institutions courtesy of the government.

The GPIF says (translated) it:

… shall manage and invest the Reserve Funds of the Government Pension Plans entrusted by the Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare, in accordance with the provisions of the Employees’ Pension Insurance Act (Law No.115 of 1954) and the National Pension Act (Law No.141 of 1959), and shall contribute to the financial stability of both Plans by remitting profits of investment to the Special Accounts for the Government Pension Plans.

Which means that it buys and sells financial products in order to build its asset structure to provide surety for pension recipients in Japan.

Its portfolio is roughly divided between bonds and shares (equities):

1. Bonds account for 50.2 per cent of total assets.

2. Shares account for 49.8 per cent of total assets.

It makes profits and losses as do all speculative ventures in financial markets.

The Japanese – National Pension System – is a three-tier system – and I wrote a detailed analysis of it in this blog post – The intersection of neoliberalism and fictional mainstream economics is damaging a generation of Japanese workers (May 8, 2025).

The welfare state in Japan is is not particularly generous and it is assumed that much of the old age support will be provided by families.

While the government welfare support is increasing in scope and magnitude, it remains that Japan is in the lower end of OECD countries in terms of welfare spending.

The system has three levels – supported by government and corporations.

1. Basic pension or Kokumin Nenkin (国民年金, 老齢基礎年金) – which provides “minimal benefits” to all citizens.

To be eligible for the full pension payment, a worker has to contribute currently ¥17,510 per month for 480 months during their working life (40 years x 12 months).

The full annual basic pension is currently ¥779,300, which is very low, especially when the recipient may not own their own housing.

A pro-rata pension can be paid if the contribution has been for at least 120 months.

2. Top-up or Fuka nenkin (付加年金) pension component – income based as a percentage.

3. Employees’ Pension or Kōsei Nenkin (厚生年金) – company pensions varying in coverage and generosity based on salary and contributions.

Many Japanese retirees are dependent on the Basic government pension.

The impact of the mainstream economic fictions on the operation of the pension system has been significant.

The government sought ways to cut the amount of benefits paid and squeeze eligibility criteria (pro-rate rules etc).

The argument was that with the ageing society (especially since increased participation of women of working age has reduced the birth rate), the Japanese government would not be able to afford to cover the pension entitlements as the proportion of workers dependent on it rose relative to those contributing to it (a rising dependency ratio).

It was decided that to ensure there was enough ‘yen’ available to provide pension benefits over the long-term that the reserves in the system (via the contributory scheme) should be invested in ‘diversified markets’.

The option was to just keep them in ‘government accounts’, which were considered to be offering inferior returns.

The logic was that the GPIF would have to generate financial returns in order to remain solvent in the long-term.

So think about the sequence:

1. Workers have to sacrifice some of their income – over a period where wages growth has been very low and real wages have been eroded to contribute to a ‘fund’.

2. The ‘fund’ then uses the workers’ contributions to speculate in financial markets.

3. And, along the way enriches the coffers of various global hedge funds and investment banks.

All because the myth that the Japanese government, which issues the currency, would run out of that currency and the aged pension system would collapse.

Poor starting assumptions leading to worse outcomes.

But the relevance of all this to the depreciating yen story is as follows.

Most commentators think that it is the responsibility of the Bank of Japan to do something about the yen depreciation.

It was argued that the Bank should increase its interest rate more quickly to attract funds into Japan and stabilise and strengthen the yen.

This approach just reflects the obsession with monetary policy that the mainstream economists have.

They think adjustments in interest rates can deal with many macroeconomic issues, including exchange rate depreciation.

Of course, when they make this recommendation in that context, they never mention the negative consequences of the interest rate rises – for example, further straining low-paid Japanese mortgage holders.

They also don’t mention that the private bank shareholders get a bonus as bank profits rise as interest rates rise.

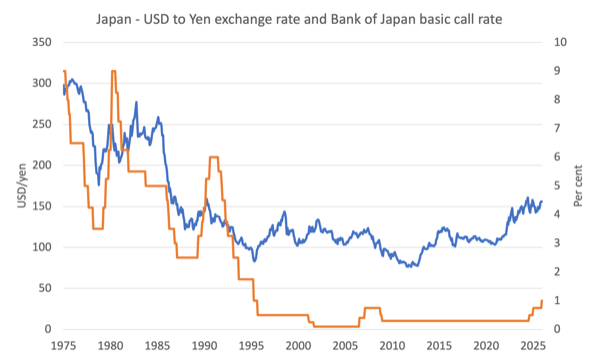

The problem for this claim is that there is very little correspondence between the interest rates that the Bank of Japan sets and exchange rate movements.

The following graph shows the USD/yen parity (as above) and on the right-hand axis is the Bank of Japan’s basic call rate over the same period.

There is no clear (mainstream alleged) relationship.

Indeed, the yen has depreciated even though the Bank of Japan has increased its policy rate.

A significant factor driving the depreciation since 2012 has been the investment behaviour of the GPIF.

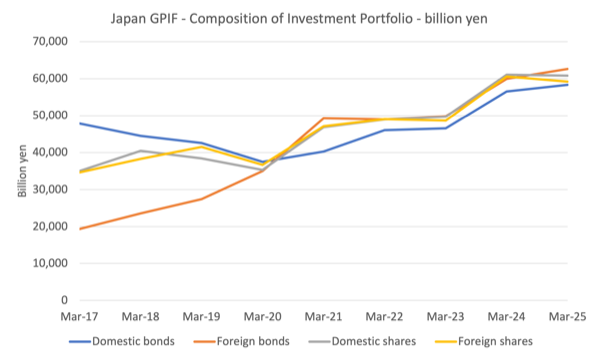

The following graph shows the evolution of the asset portfolio (investments) of the GPIF (in billions of yen) at the end of each fiscal year (end of March) from 2017.

The GPIF has shifted its investment portfolio significantly towards foreign bonds and shares over this time (the trend started post 2010).

1. In 2015, domestic bonds accounted for 41.7 per cent of total portfolio assets, foreign bonds 13.3 per cent, domestic shares 23.1 per cent, and foreign shares 21.9 per cent.

2. In 2025, the proportions were domestic bonds 24.2 per cent, foreign bonds 26 per cent, domestic shares 25.2 per cent, and foreign shares 24.6 per cent.

Question: what has this to do with the yen?

Answer: the shift to foreign investments in pursuit of higher returns has led to a significant selling of yen by the GPIF to purchase the foreign assets.

Result: yen depreciates.

So if the government was really concerned with the yen depreciation it could instruct (require) the GPIF to shift its investment portfolio back towards domestic assets.

It could also argue (unnecessarily) that the returns on domestic assets were now higher as a result of the recent Bank of Japan interest rate hikes.

But the point is that the starting point – government will run out of money myth – has led to significant institutional machinery being established (GPIF) that, in turn, then does things that have consequences elsewhere in the economy (exchange rate depreciation), that, in turn, then leads mainstream economists to demand further (unnecessary) policy changes (interest rate rises).

It is a sequence of poor assumptions leading to poor policy choices.

And all of it is unnecessary.

Conclusion

Another example of the tortured world that mainstream macroeconomics delivers.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2026 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

This Post Has 0 Comments