Well my holiday is over. Not that I had one! This morning we submitted the…

Some discussion about taxation

Over the weekend, I was a presenter at a Fabian’s Society meeting which sought input on ‘alternative taxation policies’ under the general tenet of the need for the Australian government to raise revenue to ensure a socially just society. The other presenter was John Quiggin and I think we provided a good complementarity for the relatively large audience (for a Saturday afternoon – with football finals in progress!). Of course, my opening salvo was to reject the fundamental premise of the workshop – which is a premise that progressive commentators and activists seem unable to shed to the detriment of their argument. I indicated to the audience at the outset that the aim of taxation is generally not to raise more revenue for government, but, instead, to ensure the non-government sector has less spending capacity. More is not less. That is a fundamentally different frame in which to discuss the topic and I closed the workshop by suggesting that one of the single most important things that progressives can learn is to stop using terms like ‘taxpayers’ money’ when discussing fiscal policy. Using those type of terms immediately frames the discussion against progressive goals.

The ‘taxpayers’ funds framing error

Regular readers will know that I oppose the ‘tax the rich to pay for better services’ narrative that progressive commentators seem to be obsessed with promoting.

Here are a few of my blog posts covering different aspects of that mania:

1. The tax extreme wealth to increase funds for government spending narrative just reinforces neoliberal framing (September 23, 2023).

2. Tax reform in Australia is needed but not because the government needs more of its own currency to spend (September 26, 2022).

3. Tax the rich to counter carbon emissions not to get their money (January 22, 2020).

4. The ‘tax the rich’ call bestows unwarranted importance on them (February 21, 2018).

5. Governments do not need the savings of the rich, nor their taxes! (August 17, 2015).

6. Progressives should move on from a reliance on ‘Robin Hood’ taxes (September 4, 2017).

The Australian government issues the Australian dollar as a monopolist – which means it is the only body that issues the currency.

That means it has infinity minus 1 cent dollars available for spending whenever it wants.

While infinity exists as a defined mathematical concept – boundlessness – it does not have a physical reality, which is why the government’s spending capacity is infinity minus 1 cent.

That capacity means that taxation is never required to raise funds that can then be channelled back into the economy via fiscal spending policies.

The federal government therefore is never spending ‘taxpayers’ funds’.

Taxpayers do pay taxes which involve monetary transfers from the non-government sector to the government sector.

But those transfers provide the government with no extra financial capacity, given that its capacity is infinity minus a cent dollars.

If progressives could just start with those simple propositions before they start framing policy in terms of taxes to spend, they would be in a much stronger position with respect to the debates.

I often hear progressives say that Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is all very well, but given the real politic, within which these debates are contested, it is better to rely on mainstream understandings to make the case for more government spending on progressive goals.

I remind these economists of the way that John Maynard Keynes used the (erroneous) neoclassical concept of marginal productivity theory for labour demand in The General Theory, to allow him to concentrate on the supply side, where he believed the differences between his approach and the orthodoxy could best be highlighted.

It was a decision that he regretted when it became obvious that the orthodoxy manipulated the debate to categorise Keynes’ quibbles as the special rather than the general case.

And the result was the neoclassical synthesis which dominated macroeconomics for the next several decades and allowed Monetarism an easier path and then the current New Keynesian paradigm to emerge.

The essential message of Keynes was quickly lost because he made that sort of strategic error – using neoclassical framing.

Keynes’ position (which he later acknowledged was a tactical mistake) was contested by – Roy Harrod – who was also an antagonist of neoclassical theory and a close colleague of Keynes (although Harrod was at Oxford rather than Cambridge).

Prior to the publication of Keynes’ General Theory, Roy Harrod wrote to him – Harrod to J. M. Keynes , 1 August 1935 (The letter was reprinted in Keynes, Collected Writings, vol. XIII, pp. 533-34):

as from Christ Church

1 August 1935

Dear Maynard

You may wonder why I lay such stress on a point that merely concerns formal proof rather than the conclusions reached. I am thinking of the effectiveness of your work. Its effectiveness is diminished if you try to eradicate very deep-rooted habits of thought, unnecessarily. One of these is the supply and demand analysis. I am not merely thinking of the aged and fossilized, but of the younger generation who have been thinking perhaps only for a few years but very hard about these topics. It is doing great violence to their fundamental groundwork of thought, if you tell them that two independent demand and supply functions wont jointly determine price and quantity . Tell them that there may be more than one solution. Tell them that we don’t know the supply function. Tell them that the ceteris paribus clause is inadmissible and that [b] we can discover more important functional relationships governing price & quantity in this case which render the s. and d. analysis nugatory. But dont impugn that analysis itself.

The fact that saving is only another aspect of investment makes it worse not better. If there were two separate things, saving & investment, then it is clear that the two equations will not determine both. But with one thing, then if you allowed the cet. par. clause which you rightly do not, it would be quite logical and sensible to approach it in the classical way.

Yours

Roy.

The point of the letter was to try to convince Keynes to abandon his approach that would emerge in Chapter 2 of the General Theory when he assumed a simple Classical marginal productivity theory to explain labour demand.

In adopting this assumption, which he later realised was unnecessary and empirically unjustified, Keynes opened the door for subsequent developments which perverted his message.

Ultimately, we could argue that the neo-liberal dominance now is, in part, due to that strategic error made by Keynes.

I covered that sort of problem somewhat in this blog post – On strategy and compromise (July 3, 2012).

I provide a detailed historical discussion in that blog post which I won’t repeat here.

The point is that once we start our argument with the frames and language that is used by those we are seeking to debunk, the argument is effectively lost.

I consider framing and language in a number of blog posts but this one provides a good summary – How to discuss Modern Monetary Theory (November 5, 2013).

So progressives might think they are being clever by using frames that allow them (in their own minds) to be ‘inside the tent’ and that makes them feel important – but all they are doing is reinforcing the case against them.

The ‘taxpayers funding socially progressive policies’ is a classic misstep in this regard and should never be used to advance progressive arguments.

Regressivity and progressivity

In fiscal policy, the terms regressivity and progressivity are used to describe essential features of taxation and spending decisions.

Usually those terms are applied to the taxation side – which is a huge mistake.

From the tax perspective, progressivity describes a system where the average tax rate (percentage of income paid) increases as income increases.

Conversely, regressivity is where the average tax rate decreases as income increases, which means that low-income earners endure a higher proportional burden.

Progressives regularly fall into the trap of focusing on a single element in the fiscal system – for example, a broad-based consumption tax – and then eschewing it because it is a regressive tax.

They then push for progressive taxes – such a income taxes with increasing marginal tax rates – because they think that is fairer.

The problem is that we want the tax system to be efficient and consume as few real resources as possible in terms of administration.

Income taxes, for example are much easier to evade and more costly to administer than broad-based taxes.

The point I made at the workshop on Saturday was that it is an error to just focus on individual components of the fiscal system and evaluate the desirability in terms of the regressivity or progressivity of those components.

The correct approach is to consider the overall progressivity or otherwise of the totality of spending and taxing decisions in place.

So the best tax system might be regressive overall but very efficient and the regressivity can be easily offset by highly progressive spending policies.

Tailor policies to meet the challenges

The other problem of the ‘raise revenue to spend’ fallacy is that it concentrates our attention on money amounts rather than tailoring our fiscal interventions to meet the actual real challenges before us.

I mentioned some of those challenges – inequality, degraded public infrastructure, climate change, housing crisis, excessive political influence of the rich, and more.

This then motivates us to think of why we are taxing.

Aside from tax initiatives that seek to change resource allocation – like tobacco and alcohol taxes, for example, the major reason that national governments have to tax is not to raise funds but to ensure the non-government sector has less funds.

MMT defines fiscal space not in financial terms (as in the orthodox approach) but in real resource terms.

I discussed this idea in many blog posts but this one covers the basics – Taxation is an indispensable anti-inflation policy tool in Modern Monetary Theory (June 23, 2022).

The imposition of a tax liability on the non-government sector by the government frees up real resources that would otherwise have been utilised through non-government spending.

The unemployed or idle non-government resources can then be brought back into productive use via government spending which amounts to a transfer of real goods and services from the non-government to the government sector.

In turn, this transfer facilitates the government’s socio-economic program.

While real resources are transferred from the non-government sector in the form of goods and services that are purchased by government, the motivation to supply these resources is sourced back to the need to acquire fiat currency to extinguish the tax liabilities.

Further, while real resources are transferred, the taxation provides no additional financial capacity to the government of issue.

Conceptualising the relationship between the government and non-government sectors in this way makes it clear that it is government spending that provides the paid work which eliminates the unemployment created by the taxes.

And the scale of this relationship – or, in other words, the size of government – then dictates the scale of the (initial) unemployment created by the tax liability.

Relatively large governments require large tax revenues, while smaller footprint governments require smaller tax takes.

But note that scaling relationship is not about ‘funding’.

It is about creating the non-inflationary real resource space to absorb the scale of government spending desired.

The policy design must ensure that the tax revenue is sufficient – and depriving the non-government sector of resource usage – to accommodate the scale of spending desired.

While the orthodox conception is that taxation provides revenue to the government which it requires in order to spend, the MMT conception is that the tax revenue is an indispensable policy requirement in order to ensure the government can operate at its desired scale, without pushing the economy into an inflationary episode.

Some suggested tax innovations

I will write more about this topic in subsequent posts but for now this is what I discussed at the workshop on Saturday.

John preferred to raise the marginal tax rate for high income earners to 60 per cent from the current rate of 45 cents in the dollar for incomes $A190,001 and over.

I am not sure whether he wanted to raise the next tax rate band – marginal rate 37 cents in the dollar between $A135,001 and $A190,000.

I have no issue with that proposal but I would not prioritise it given the difficulties in collection and the capacity for high-income earners to tax evade.

I went through a number of alternatives – abandon the tax concessions on investment properties which basically deliver massive bonuses to those with multiple properties (given the capital gains tax is inadequate) and those bonuses are biased towards the top end of the income and wealth distribution.

I said I preferred the government to abandon the very generous concessions to superannuants – which has become a major way that income inequality is increased.

Those with very high pensions can essentially get tax free income.

I preferred though to concentrate on the introduction of a wealth tax and death duties (inheritance taxes).

There is no wealth tax in Australia.

We used to have death duties levied at the state/territory level but the Queensland government became infested with the ‘Abolition of Death Duties’ movement which emerged in the late 1960s.

In 1977, the Queensland state government abolished all death duties.

The other states then were forced to follow suit for fear of losing their tax bases as a result of a ‘flight of capital’ to the sunny climes of Queensland.

By 1982, all the states and territories had abandoned the tax.

At the federal level, Estate Duties as they were known were abandoned in 1979.

We should definitely consider reintroducing Estate Duties at the federal level – which would stop all the ‘smokestack chasing’ (competition between the states and territories for capital) that would arise if one state tried to introduce death duties alone.

But the real action should be in the area of a wealth tax.

In Australia, like most countries, there is a high degree of wealth inequality.

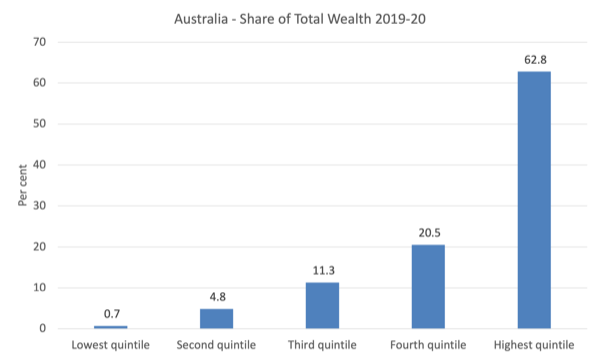

The following graph shows the shares of total wealth by quintile for 2019-20 (latest data).

60 per cent of the households in Australia have just 16.8 per cent of the total wealth.

The top quintile comprises around 2,030 households with a net worth range of $A1,400,000 to over $A10 million.

The top decile comprises around 1,180 households with a net worth range exceeding $A2 million.

The distribution will not have changed much since 2020 although the nominal net worth amounts will have increased substantially as a result of the latest real estate bubble.

A wealth tax would address the problem of increasing net worth inequality (the Gini coefficient has risen from 0.602 in 2009-10 to 0.611 in 2019-20).

It would also help advance our goal of reducing the capacity of the wealthy in Australia to influence the political process through lobbying and media ownership etc.

Most opposition for a Wealth tax is based on the double taxation argument – the wealth is a stock that has been accumulated, so the argument goes, by being thrifty with income flows, which have already been taxed via the income tax system.

Does that argument stand up to scrutiny?

The National Accounts data allows us to interrogate the proposition.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics releases the – Australian National Accounts: Finance and Wealth – data (latest edition for March-quarter 2025 released on June 26, 2025).

It is always released after the main expenditure data which came out last week and applies to the June-quarter 2025.

The latest Finance and Wealth data shows that:

Household wealth grew 0.8% ($137.1b) to $17,309.7b by the end of the March quarter. The increase in net worth was driven by land and dwelling assets …

Non-financial assets owned by households increased by 1.2% ($151.8b). The value of residential land and dwellings increased $125.3b or 1.2 per cent, with both property prices and the number of dwellings increasing during the quarter.

The overwhelming gains in household net worth do not come from savings out of income earned through work but via capital gains (mostly on housing).

So the ‘double taxation’ argument, even on its own terms is specious when applied to Australia.

The Capital Gains taxation in Australia is also highly concessional with the so-called ’50 per cent discount’ being introduced in 1999, which means that the income flowing from these gains is taxed at half the usual rate of income tax.

I haven’t time today to write about a Wealth tax scenario that we have been developing at the Centre of Full Employment and Equity (CofFEE).

Suffice to say that there is massive scope to prune the wealth of the top end of the distribution and the rest of us wouldn’t notice a thing.

Conclusion

In a later blog post, when the new wealth data is available I will write up the model we have been developing.

Even a modest wealth tax would have an impact on the capacity of the top end to manipulate the political system.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“Suffice to say that there is massive scope to prune the wealth of the top end of the distribution and the rest of us wouldn’t notice a thing.”

That would assume legal tax incidence and economic tax incidence are the same, and they are not. The wealthy see tax as a cost and pass it on the same as any other cost. They retain the power to do that.

Which is why all taxation ends up increasing unemployment in the first instance. The powerful extract via increased cost. Particularly in any environment where ‘tax and spend’ still holds sway and the spend ends up validating the cost increases.

The empirical evidence seems to show that the most effective tax to collect is a PAYE tax, where the tax is collected on behalf of somebody else and paid over by a third party before the individual ever gets their income in the first place. Which is the same trick that makes consumption taxes collectable, but also impacts money that is earned but isn’t spent. Anti-avoidance is then about making income pass through this third party mechanism, no matter what its form.

Consumption taxes run into a wall once you get into the import and export arenas. They complicate matters immensely particularly if the consumption tax is a value add tax.

UK Tax gap analysis by HMRC suggests 1% for PAYE, and 5% for VAT. Property taxes are about 4%. Profit based taxes are worse than duty avoidance on tobacco and alcohol – up to 22%.

Once you run through the trade offs you end up with some sort of area/volume based property tax to provide the broad tax need to drive the currency, and some sort of employment tax calculated and paid over by employers to provide the specific tax needed to release resources. The salience and incidence of those appear to have the lowest leakage from the initial target from what little empirical data there is.

Still not sure if the transaction taxes impact the effectiveness of the Job Guarantee mechanism, or the stability of the currency (as they cause the base tax demand to change over the cycle).

Lots to do in this area.

Hi Bill,

OK, if I can simplify your argument and correct me if I am wrong:

1 – taxation is not a revenue creation tool, but rather a revenue destruction tool.

1a – Both descriptions conclude that the ultimate objective of taxation is the creation of economic space for government intervention in the market economy

1b – you suggest that your description of how we get there has consequences on the way government should tax and spend and also introduces an important side effect of taxation: significant influence on inflation.

2 – You seem to suggest that “taxation justice” is not as important as taxation efficiency because,

2.1 – taxation’s main objective is to destroy private revenue whatever its nature and

2.2 – any injustice in revenue destruction can be compensated later by government targeted (“just”) spending

Questions:

Question 1 : this point 2 is somewhat confusing, 2.2 appears to me as an inefficient way to obtain social justice, plus it risks inflation because you need more government spending to abate inequality than what you would otherwise spend if revenue destruction had been targeted in the first place

Question 2: if taxation is all about private sector revenue destruction and administration efficiency then does that not give credence to right wing initiatives to abolish corporate and income taxation or get rid of tax bands and just have a single universal band? doesn’t your argumentation suggests that a taxation system should only be targeted at “vices” (i.e. purchase/production of certain items we deem undesirable: alcohol, tobacco, CO2, sewage) + efficient destruction of revenue to the level necessary to achieve the government we want – what I mean is, are you not incurring in the risk of sounding a bit like F. Hayek?

Question 3: If government financial balances are not only an unnecessary myth but also incapable of determining the “economic space” (traditional economists’ would call it “fiscal space”) the government can safely occupy then what other tool do you propose to measure “space for government intervention”? how do you measure “economic space” for government intervention without regularly stumbling into significant inflationary episodes?

Thank you for your patience.

When you say “(…) the aim of taxation is generally not to raise more revenue for government, but, instead, to ensure the non-government sector has less spending capacity.”, it doesn’t apply to the dystopian eurozone.

In the eurozone, taxation is a tool for wealth transfer from one class to another.

Theoretically, taxation can go either way: transfer from the wealthy to the lower/middle classes (what F.D. Roosevelt did almost 100 years ago) or from the lower/middle classes to the wealthy.

In the last 50 years (I’m almost 58), it’s never been the former way.

When I was a teenager, there where millionaires; now, there are billionaires (and we are on the track to have trillionaires): just imagine how tax cuts work so well for them…

Instead of paying taxes to the state, the wealthy are lending the state the money they haven’t paid as taxes, overcharging the public finances with debt (hello Argentina).

The answer for all those troubles seems to be the election of buffoons.

Charlatans have only one answer to all our troubles: more neoliberal mantras.

Lowlander,

Point 2 in your comment misstates the case. It focuses on a side issue that bill (perhaps unwisely) has left open. The essential purpose of taxation is to give the government access to resources it needs to implement its policies, even if those resources are already in use by private actors.

Taxing very poor people would give the government access to the resources those poor people would have spent the money on if it hadn’t been taxed away. Most policies probably can’t be implemented using those things.

Back when, Steve American brought this issue up. Many many times economic issues are framed in financial terms (eg. destruction of revenue), and this makes calculation and theorizing simpler, but leaves out a big part of the world.. Economics deals with your question 3 with factor analysis, laying out and studying the way resources are combined to produce goods. Seems to me that factor analysis is hugely complicated, since it involves bringing in most of the real world. So we work with money numbers, an hope that that will sometimes be enough.

“In adopting this assumption, which he later realised was unnecessary and empirically unjustified, Keynes opened the door for subsequent developments which perverted his message.”

I would be interested in reading those later writings where Keynes expressed his regret with the way he had framed things in the GT. Can you cite some in particular? Thanks.

Regardless of other macroeconomic management intent, if a goal of taxation is to perform a left egalitarian political objective of reducing wealth differentials then there has to be a two pronged approach that separates taxing ‘flows’ from taxing ‘stocks’.

Taxing revenue and taxing capital for redistribution objectives requires different approaches and also different rationales.

I look forward to Bill taking up where he has left off, on wealth, other capital taxes and alternative redistributive policies.

The key objection to wealth taxes, even from left of centre commentators, is that they are too difficult to implement and too easy to evade.

On the left, we all know that there is an increasing mass of empirical evidence across a number of fields, not merely economic, that extreme concentrations of wealth are exceptionally socially and politically damaging and that a much smaller range in wealth distribution is highly desirable, and some would say an existential necessity. This is both a pragmatic and idealistic goal, as a stable society is in everyone’s interests.

Yet the case for both narrower earnings differentials, as well as wider distribution, is often assumed and not argued from first or second principles, or numbers applied.

For example, what would be an equable earnings differential within a work hierarchy? 10x, 25x, 50x, 500x?

We know CEO to shopfloor ‘earnings’ ratios have accelerated, especially since 1979, but what is an acceptable differential?

Would a comparison across nation states, say between the Scandi social democracies, SE Asian states, post-industrial EU and North American states be useful ?