I don't have much time today as I am travelling a lot in the next…

How to discuss Modern Monetary Theory

I have been travelling a lot today (nearly 6 hours starting early) and so haven’t much time for blog writing. I am working on a paper at present on the use of metaphors in economics and how Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) might usefully frame its offering to overcome some of the obvious prejudices that prevent, what are basic concepts, penetrating the public psyche. Here are some notes on that theme. The blog is just a rough sketch and will be refined over the coming weeks. There is a section at the end that encourages reader feedback – lets see what you think.

Framing

Macroeconomics is an area of study that is fraught with controversy. Macroeconomics is seen as being of significant national importance but the concepts that are involved in understanding macroeconomic functions are difficult to understand well.

For example, what is an aggregate price level? How do we understand a budget deficit or a budget surplus? And are all budget deficits the same?

Macroeconomic concepts are discussed in the media on a daily basis, such as, the real GDP growth rate, the inflation rate, the unemployment rate, the budget deficit, and the interest rate.

Finance segments on national news broadcasts, introduced over the last three decades or so, increasingly expose the public (and journalists) to macroeconomic terminology, without a commensurate increase in the degree of education associated with the terminology or concepts.

Further, the advent of social media has made it possible for anyone to become a macroeconomic commentator: the so-called blogosphere is replete with self-styled macroeconomic experts who make claims about the state of the federal budget, often relying on “common sense” logic to make their cases.

The problem is that common sense is a dangerous guide to reality and not all opinion should be given equal privilege in public discourse. Our propensity to generalise from personal experience, as if the experience constitutes general knowledge, dominates the public debate – and the area of macroeconomics is a major arena for this sort of false reasoning.

The surge in public interest in matters macroeconomic has been channelled by the dominant neo-classical paradigm in economics. As a consequence, the public understanding becomes straitjacketed by orthodox concepts and conclusions that, in themselves, are erroneous, but also lead to policy outcomes that undermine prosperity and subvert public purpose.

The abandonment of full employment in the 1980s and the willingness to tolerate mass unemployment is a manifestation of this syndrome.

The dominant macroeconomics paradigm, which prior to the global financial crisis had pronounced that the business cycle was largely dead and that we had entered a period of “great moderation”, categorically failed to foresee the consequences of the labour market and financial deregulation that it had promoted.

We would argue that its lack of empirical content and its demonstrated failure to predict novel facts (the GFC) renders the mainstream macroeconomics a pseudo-scientific, degenerative research program following the classification scheme proposed by Imre Lakatos in 1970.

However, any sense that the crisis would lead to a major examination of the role of mainstream economics and action to change the curricula taught and research agendas pursued were short-lived. Mainstream economists exercised their anti-government free-market biases and effectively reconstructed what was a private debt crisis into a sovereign debt crisis. The dynamics that created the crisis (deregulation, reduced financial oversight) continue to be advocated by the mainstream as solutions.

The public debate is dominated by claims that fiscal austerity is the only viable path to recovery and leading multilateral agencies such as the IMF and the OECD have produced glowing forecasts, which denied that major fiscal retrenchments would damage growth.

This view was unchallenged by media commentators. Subsequently, the IMF has been forced to admit its calculations were in error (IMF apology article) although this admission, stunning for what it represents, has had little impact on the dominant discourse.

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is a coherent, internally consistent and well-developed macroeconomics framework, which is ground in the operational reality of the capitalist monetary economy.

Its track record in explaining major events over the last two decades (including the global financial crisis and its aftermath) suggests that it is a progressive research program (in the Lakatosian sense) capable of predicting novel facts, which are confirmed by subsequent events.

In this regard, MMT is a superior basis for macroeconomic reasoning relative to the dominant neo-classical approach.

But the problem is dealing with the way the dominant macroeconomics paradigm frames its argument. Why does the emerging MMT approach, which though superior in the ways noted above, fail to resonate with the wider public.

Framing refers to the way an argument is mounted or pursued in the public debate. Cognitive linguists have shown that the way we understand complex issues is via metaphors and neo-classical macroeconomics has been extremely successful in its use of common metaphors to advance their ideological interests (the work of George Lakoff is prominent).

It is apparent that we end up believing things and supporting policies that actually undermine our own best interests because of the way the arguments are presented to us. In other words, we accept falsehoods as truth and ideology triumphs over evidence.

Recent psychological studies have highlighted the extent to which pre-existing biases influence the way in which individuals interpret factual information, including straightforward statistical data.

This presents a problem for the communication by researchers to the public of research outcomes that bear on public policy design, particularly where findings may be counter-intuitive, or may challenge a dominant or controversial discourse, as in the case of economic austerity or climate change.

The aim of the paper we are working on at present – with some notes presented below – is that we consider the evolution of MMT as a viable consistent alternative but recognise that the language deployed by progressives and conservatives in communication about key macroeconomic concepts undermines the successful communication of insights arising from MMT.

We aim to provide a conceptual basis for understanding how language matters (the contribution of my co-author who knows about these things) and examine some of the key metaphors used to reinforce what the flawed message of orthodox economics and examine key ideas of modern monetary theory and propose effective ways of expressing those key ideas.

Fellow MMT colleague Randy Wray and others have explored the metaphors that underpin the language that is commonly used to describe macroeconomic operations and outcomes.

There has, however, been limited work in the linking of metaphorical language to values and the way language reinforces or undermines a particular value or set of values. That is our aim.

The economy is Us

People created the economy. There is nothing natural about it. Concepts such as the “natural rate of unemployment”, which imply that the economy is a natural system, which should be left to its own equilibrating forces to reach its natural state, like any living system.

But when we use terms like natural we have to ask – natural in relation to what? The mainstream define the problem away rather than address the ideological benchmark that the term “natural” disguises.

The reality is that human interaction and choices, initially simple and localised, and later, significantly more complex and spatially distributed (globalised), creates what we call the economy. We are in charge here.

At some point, we realised that we needed an agent to do things that we could not do ourselves – either easily or at all. We formed governments. We also came to understand that our creation – the economy – would only serve our common purposes if it was subject to oversight and control by our agent.

We had operated under the mistaken view that this agency role was unnecessary because our spontaneous interactions would sort things out in our favour. It didn’t happen and when the consequences of this failure became so obvious – during the Great Depression – we accepted the agency role as being fundamental to ensuring that the capitalist monetary system behaved itself.

We learned then that capitalism which had developed into a broad system of wage labour was subject to basic tensions between labour and capital. We also learned that the so-called “market” signals (prices that brought demand and supply together) would not deliver employment outcomes that satisfied the desires of labour for work.

We learned that this system could easily equilibrate (a state where there was no further dynamic for change) in a state of mass unemployment. The Great Depression taught us that our agent (the government) could ensure that the system did not get stuck in this state because it had the spending capacity to ensure that total spending in the economy generated enough output that would fully employ all those who wanted work.

The simple understanding of that period was that the economy was a construct we could control in order to create desirable collective outcomes such as improved living standards – better housing for all, improved public education and health standards etc. All outcomes that required real resources to be brokered by the public sector in cooperation with the private firms and workers.

While there was a strong conservative element that resisted the Post-World War 2 consensus, the government mediated the class conflict to ensure the system did deliver social as well as private returns. We understood that if employment fell it was because there wasn’t sufficient demand and because the economy was us, we knew what to do about it – spend more. The question was how would this be accomplished.

Economists certainly understood that private spending could become stuck – while the unemployed certainly had a demand for goods and services, they only sent a notional signal to the firms of that desire. The private market only works on effective demand and supply signals – that is, demand intentions backed by cash and the unemployed didn’t have any cash because they had lost their job and employment provides income which funds spending.

While the way the macroeconomists spoke of such things was reserved for the academy (full of jargon etc), the concepts were also broadly understood by the public and we knew that a government budget deficit was required to ensure that total spending was sufficient (for full employment) when the rest of us (the non-government sector) were not recycling all our current income back into the spending stream (that is, saving).

The period of neo-liberal smugness

In the 1980s and beyond, the mainstream revision of the past gathered pace.

Weber (1997: 71) wrote that the rise of the “New Economics”, characterised by the:

… globalization of production, changes in finance, the nature of employment, government policy, emerging markets, and information technology, had contributed] … to the dampening of the business cycle.

[Reference: Weber, S. (1997) ‘The End of the Business Cycle?’, Foreign Affairs, 76(4), 65-82]

The “facets” which had smoothed out growth and supply shocks would now be:

… less important in a more flexible and adaptive economy that adjusts to shocks more easily and with less propensity for sparking a new cycle (Weber, 1997: 71).

Weber also implicated the decline in union strength, more flexible labour markets, and the rapid growth of the financial sector as contributing to the end of the business cycle.

He said that the “enormous growth” in derivatives trading was beneficial because “(t)hese new financial products spread and diversify risk” and that the new class of funds managers were “better at using these new tools to stabilize financial flows and protect themselves against shocks” (1997: 74). The financial sector was seen as lubricating “increasingly efficient” global capital markets and had created an array of “shock absorbers that cushion economic fluctuations” (1997: 75).

He also said (1997: 80) that the “current consensus on inflation among central bankers” will “also constrain states’ fiscal policies” and that the “inherently cyclical nature of government spending will decline as business cycles dampen”.

Weber (1997: 75) concluded that “doomsday” arguments “that complex markets might act in synergy and come crashing down together is simply not supported by a compelling theoretical logic or empirical evidence.” Such views were increasingly common among mainstream economists as the new century approached.

In 2002, Harvard economists James Stock and Mark Watson captured this sentiment and noted that the US economy was “quiescence” which reflected “a trend over the past two decades towards moderation of the business cycle and, more generally, reduced volatility in the growth rate of GDP” (Stock and Watson, 2002). They termed this trend the “great moderation” (2002: 162).

[Reference: Stock, J.H. and Watson, M.W. (2002) ‘Has the Business Cycle Changed and Why?, in Gertler, M. and Rogoff, K. (eds.), NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2002, Volume 17, MIT Press, 159-218]

On February 20, 2004 the current US Federal Reserve Board Governor Ben S. Bernanke presented a paper in Washington entitled “The Great Moderation” (Bernanke, 2004), which summarised the views held by the vast majority of economists that the business cycle was dead!

[Reference: Bernanke, B.S. (2004) ‘The Great Moderation’, paper presented to the the Eastern Economic Association, Washington, DC, February 20, 2004, available at: http://www.federalreserve.gov/BOARDDOCS/SPEECHES/2004/20040220/default.htm]

The celebratory, smug confidence of the mainstream economists is best summarised by Robert Lucas Jnr. in his presidential address to the American Economics Association (2003: 1):

Macroeconomics was born as a distinct field in the 1940’s, as a part of the intellectual response to the Great Depression. The term then referred to the body of knowledge and expertise that we hoped would prevent the recurrence of that economic disaster. My thesis in this lecture is that macroeconomics in this original sense has succeeded: Its central problem of depression prevention has been solved, for all practical purposes, and has in fact been solved for many decades. There remain important gains in welfare from better fiscal policies, but I argue that these are gains from providing people with better incentives to work and to save, not from better fine-tuning of spending flows. Taking U.S. performance over the past 50 years as a benchmark, the potential for welfare gains from better long-run, supply-side policies exceeds by far the potential from further improvements in short-run demand management.

The message was simple. The mainstream economists had triumphed over the interventionists who had over-regulated the economy, undermined the incentive from private enterprise, allowed trade unions to become too powerful, and bred generations of indolent and unmotivated individuals who only aspired to live on welfare support payments.

This triumph manifested at the policy level by the primacy of monetary policy in counter-stabilisation, where the primary policy target became inflation stability. Fiscal policy was rendered a passive subordinate and governments abandoned their responsibilities to maintain full employment.

We considered these arguments in detail in our 2008 book – Full Employment abandoned.

The sentiments expressed by Lucas coincided with the major shift in policy direction towards so-called microeconomic reform, which resulted in extensive financial and labour market reform. The pre-conditions for what was to become the global financial crisis were set in place during this period.

Real wages growth started to lag behind productivity growth as a result of attacks on unions and the rising precariousness of work (increased casualisation and rising underemployment), which undermined the capacity of workers to pursue adequate recompense.

The loss of capacity to maintain consumption growth was overcome by the burgeoning financial sector, which grew rapidly on the back of a massive increase in private sector debt, increasingly provided to more and more marginal borrowers then packaged up into complex derivatives and on-sold to the next sucker.

The official narrative was that of Lucas – the business cycle was largely dead.

This view of the world was buttressed with a vehement political campaign which sought to dispose of the binding concepts such as collective will etc in favour of promoting the view of the economy as a natural system delivering outcomes to individuals in accordance to their contributions.

They promoted the economy as a self-regulating system.

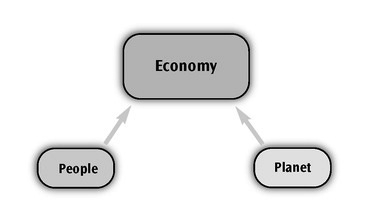

In her book, Don’t Buy It, Anat Shankar-Osorio juxtaposes two models of the economy. The first depicted in the following graphic which she considers represents the conservative view (although there are progressives that would be lumped into this category).

Accordingly, the driving image is that “people and nature exist primarily to serve the economy” (Location 439). The economy is removed from us and is a moral arbiter, which recognises our endeavour and rewards us accordingly. Those who do not work hard and sacrifice for the “economy” are deprived of such rewards.

But if the “government” intervenes in the competitive process and provides an avenue where the undeserving (lazy, etc) still receive rewards then the system malfunctions and becomes “sick” (a metaphor that the economy is a living thing) and the solution is to restore its natural processes (aka getting rid of government intervention such as minimum wages, job protection, income support etc).

So “self-governing and natural” are the messages we receive, which leads to the obvious conclusion that “government ‘intrusion’ does more harm than good, and we just have to accept current economic hardship” (Location 386).

Our success then is somehow independent of the success of the economy. The hallmarks of a successful country are whether real GDP growth is strong irrespective of whether “this comes at the expense of air quality, leisure time, life expectancy, or happiness … all of these are secondary”.

If poverty rates are rising, the construction is that the person is just not doing enough for the economy rather than the economy failing, in its current operations, to do enough for us. We are to blame for our own failures. They arise because we don’t contribute enough. How can we expect to be rewarded for a sub-standard contribution to the success of the economy?

Progressives get sucked into this narrative and offer up “fairer” alternatives within, for example, the austerity debate. Take the current debates in the advanced nations.

None of the major (progressive) political parties are challenging the austerity dogma. You will often read a progressive commentator writing something like … “we know the deficit is a problem and public debt has to be reduced, but we think this should be done more gradually”.

At that point, both sides of the debate are effectively singing off the same hymn sheet and the public discretion gets lost in the fog. The basic propositions are root-and-branch wrong but the solutions seem obvious and the different value-systems (conservative and progressive) are left to argue about matters of degree.

Towards an alternative

In the early 1990s, as the neo-liberal credit binge was beginning, the early proponents of what is now broadly known as Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) – this was a small group (Mosler, Mitchell, Wray, Forstater, Fullwiler, Tcherneva then Bell/Kelton) – drew on earlier heterodox theory (functional finance etc) and added particular operational insights about the monetary system – to develop an alternative narrative about the way the monetary capitalist system operated.

They used this narrative to expose what they saw was an unsustainable dynamic fostered by the mainstream belief that self regulating markets would deliver maximum wealth to all.

Even in those early stages of the private debt build-up it was clear that a major crisis was approaching, given the ill-considered financial practices that were emerging.

Other progressive economists, however, were not so engaged. They were mostly intent on focusing on issues such as gender, sexuality, method and, as such, provided a fragmented, and easily dismissed critique of the mainstream economics narrative.

There was also hostility with progressive ranks to the growing literature being produced by the proponents of MMT.

The Great Moderation was brought to a stark halt by the global financial crisis, which began in early August 2007 when the French bank BNP Paribus stopped withdrawals from three investment funds in response to the growing concern about the viability of the sub-prime loan portfolios. Later in the same month, there was a run on the British bank Northrock.

As the wealth that had been built up during the Great Moderation started to prove illusory, with housing and share prices falling sharply, the crisis escalated. In September 2008, Lehmans collapsed.

At that point, the myth of self-regulating markets was exposed and the entire edifice of mainstream economic theory lost creditability – none of the dominant Neo-Keynesian models taught in universities or used by academics in scholarly articles was equipped to predict the crisis or offer viable solutions to the crisis.

Finally, it was clear to all that the emperor had no clothes.

The initial response to the crisis of the mainstream economists was silence although there were notable exceptions.

On October 23, 2008 as the crisis was escalating, the former US Federal Reserve Chairman appeared before the US House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, which was investigating the “The Financial Crisis and the Role of Federal Regulators”.

The Chairman of the Committee, Henry Waxman asked Greenspan whether his free market ideology that pushed him to make regrettable decisions. He replied (US House of Representatives, 2008, page 36-37):

Mr. GREENSPAN. Well, remember, though, whether or not ideology is, is a conceptual- framework with the way people deal with reality. Everyone has one. You have to. To exist, you need an ideology.

The question is, whether it exists is accurate or not. What I am saying to you is, yes, I found a f1aw, I don’t know how significant or permanent it is, but I have been very distressed by that fact …

Chairman WAXMAN. You found a flaw?

Mr. GREENSPAN. I found a flaw in the model that I perceived is the critical functioning structure that defines how the world works, so to speak.

Chairman WAXMAN. In other words, you found that your view of the world, your ideology, was not right, it was not working.

Mr. GREENSPAN. Precisely. That’s precisely the reason I was shocked, because I had been going for 40 years or more with very considerable evidence that it was working exceptionally well.

However, any sense that the crisis would lead to a major examination of the role of mainstream economics and action to change the curricula taught and research agendas pursued were short-lived.

The mainstream profession began to reconstruct what was a private debt crisis into a sovereign debt crisis, which suited their anti-government, free market biases.

The dynamics that had created the crisis (deregulation, reduced oversight) were advocated as solutions. The public debate was flooded with claims about that fiscal austerity was the only viable path to take and leading multilateral agencies such as the IMF and the OECD produced glowing forecasts, which denied that major fiscal retrenchments would damage growth.

Subsequently, the IMF has been forced to admit its calculations were in error (IMF apology ARTICLE).

So while the MMT narrative has had a high predictive value its capacity in influencing the public debate has been close to zero.

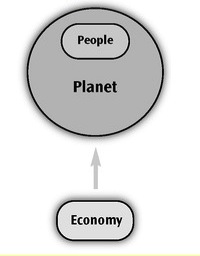

Shenker-Osorio (2012) provides this alternative conception of the economy, which is consistent with the view that it is our construct and not something separate from us.

She writes (Location 1037):

This image depicts the notion that we, in close connection with and reliance upon our natural environment, are what really matters. The economy should be working on our behalf. Judgments about whether a suggested policy is positive or not should be considered in light of how that policy will promote our well-being, now how much it will increase the size of the economy.

Or we might add – how much it adds to the budget deficit or public debt.

Her suggestions sits squarely with the principles of functional finance – that we see the economy as a “constructed object” – and policy interventions should be appraised only in terms of how functional they in relation to our broad goals.

We thus need to elaborate more fully what the goals that we seek to achieve are. A particular budget deficit, for example, is a meaningless goal.

The budget balance will be whatever it is – in relation to our goals and the functional relationship that net public spending has in relation to those goals.

The government is not a moral enforcer and the economy is not a morality play.

Metaphors and Values

There is a progressive literature (for example, the Common Values Handbook) which attempt to articulate the values considered to be “our guiding principles” which influence “the attitudes we hold and how we act”. Extensive research has “identified a number of consistently-occurring human values” (Common Values Handbook, 2012: 8).

This research that is drawn upon largely centres around the work of Schwartz and his value circumplex. He identified 10 basic and universal human values which frame the way we think.

Our view – which will be elaborated in the paper – is that this discussion is somewhat of a side-show. The values are so general that any idea can be consistent with them.

We prefer to concentrate on developing some broad principles and working on a language to support them.

Broad principles and terminology

Some broad principles to develop might be:

1. The Government is Us!

2. The government is our agent and like all agents we cede resources and discretion to it because we trust that it can create benefits for all of us that each on of us individually cannot achieve. We understand scale.

3. Governments invest in our immediate well-being by providing essential services without the need for profit.

4. Governments invest in the next generation’s well-being through building productive infrastructure that delvers services for decades.

5. We empower governments with unique characteristics so that it can pursue our interests without the constraints we face ourselves.

6. We understand that a deficit for us means we have to find funds to cover it, whereas a deficit for our agent, the currency-issuing government means it is funding our spending and saving choices.

7. A government deficit enhances our freedom because it boosts our income and allows us more options.

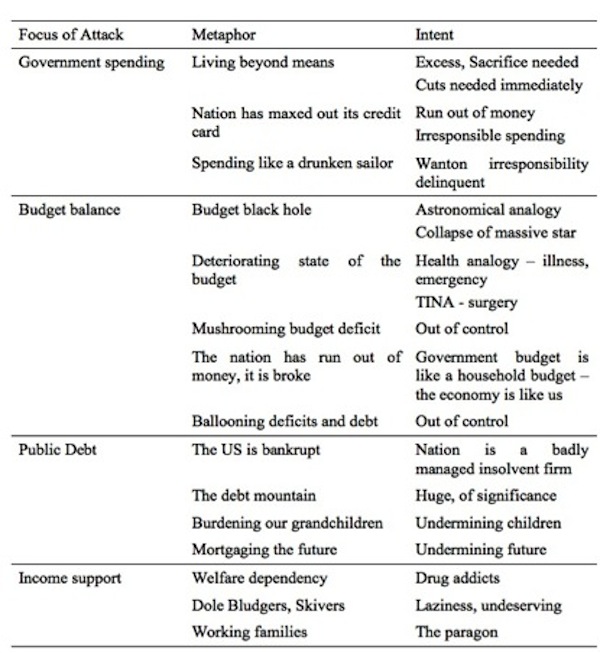

Face to Face – Mainstream and MMT

The following Table presents the mainstream propositions that are used by economists and commentators to focus their attack on government spending, deficits, public debt and income support payments for the most disadvantaged workers.

In the paper we will show that example reinforces several of the main core values that the mainstream paradigm seeks to promote, such as, self-discipline; independence; ambition; wealth and sacrifice.

Each of these false propositions is backed up by a series of metaphors that disguise the myth.

The operational reality that MMT offers for each proposition is in column two. The issue is – how to communicate the ideas in the MMT column to the wider public.

| Mainstream macroeconomics | Modern Monetary Theory |

|---|---|

| Budget deficits are bad | Budget deficits are neither good nor bad and are required where the spending intentions of the non-government sector are insufficient to ensure full utilisation of available productive resources. |

| Budget surpluses are good | Budget surpluses are neither good nor bad and may be harmful in some circumstances if they involve a drag on growth in situations where there are idle resources. |

| Budget surpluses contribute to national saving | There is no sense to the concept that a currency-issuing government saves in its own currency. Saving is an act of foregoing current spending to enhance future spending possibilities and applies to a financially-constrained non-government entity. The government never needs prior funds in order to spend and thus never needs to “save”. |

| Budget should be balanced over the business cycle | Budget should be allowed to adjust to the level of net spending required to achieve and sustain full employment given the spending decisions of the non-government sector, irrespective of the state of the business cycle. |

| Budget deficits drive up interest rates because they compete for scarce private saving | Private saving is not finite and is related to income. Spending always brings forth its own saving because saving rises and falls with income movements, which are directly related to movements in spending. |

| Bond markets determine funding costs of government | Central bank sets interest rate and can control any segment of the yield curve it chooses. The costs of government spending are the real resources that are utilised in any particular public program. |

| Budget deficits mean higher taxes in the future | Budget deficits never need to be paid back. Every generation can freely choose the level of taxation it pays. |

| The government will out of fiscal space (money) | Fiscal space is more accurately defined as the available real goods and services available for sale in the currency of issue. The currency-issuing government can always purchase whatever is for sale in its own currency. Such a government can never run out of its own currency. |

| Budget deficits equals big government | Budget deficits may reflect large or small government. Even small governments will need to run continuous deficits if there is a desire of the non-government sector to save overall and the policy aim is to maintain full employment levels of national income. |

| Government spending is inflationary | All spending (private or public) carries an inflation risk. Government spending is not inflationary while ever real resources are idle (ie. There is unemployment). All spending is inflationary if it drives nominal aggregate demand faster than the real capacity of the economy to absorb it. |

| Issuing bonds to the private sector reduces the inflation risk of deficits | There is no difference in the inflation risk attached to a particular level of net public spending when the government matches its deficit $-for-$ with bond issuance relative to a situation where it issues no debt. The inflation risk is embodied in the spending rather than the monetary arrangements that are associated with it (bond-issuance or not). |

| Intergenerational burdens are linked to inherited budget deficits in the form of debt that have to be paid back. | Intergenerational burdens are linked to the availability of real resources. For example, a generation that exhausts a non-renewable resource imposes a burden on the next generation. A future generation cannot transfer real resources back in time. |

| Unemployment is used to control inflation rate | Employment is used to control inflation rate |

| Sovereign issuer of currency is at risk of default | Sovereign issuer of currency is never at risk of default. The issuer of a currency can always meet any liabilities it incurs in that currency. |

| Taxpayer money | Public currency. The taxpayer does not fund anything. Taxes are a device to free up real resources so our agent, the government can instigate a socio-economy program for our collective benefit. |

| Humans make rational decisions based on self-interest | Humans are complex and rarely predictable, reason and emotion are inseparable. |

The following graphic captures some examples of mainstream neo-classical macroeconomic metaphors which are used to reinforce the erroneous propositions summarised in column one of the above Table.

Terminology

There is a broad current of opinion that MMT has to avoid so-called loaded terms. Here are two examples.

Statement 1: Mass unemployment is a sign that the budget deficit is too small

This is a correct conclusion.

There are two problems with using the term budget deficit. First, the term has a negative connotation because a deficit signifies a shortfall.

In an accounting sense, a deficit is a shortfall of revenue given spending.

Second, movements in the budget balance are ambiguous and cannot be assessed in a qualitative manner without further, detailed and technical scrutiny.

A given budget outcome can be signal that the deficit is “good”, if it has arisen as a result of discretionary fiscal policy decisions by government to maintain full employment given the spending and saving decisions of the non-government sector; or “bad”, if it has arisen because non-government spending has fallen and the automatic stabilisers have led to a decline in tax revenue and an increase in unemployment.

The focus also leads us to conclude that the government, in fact, controls the budget outcome. The reality is that the final outcome reflects discretionary decisions made by government and spending and saving decisions by the non-government sector.

So the terminology is problematic and the reality quite complex.

There are those who suggest we stop using the term “deficit” and “surplus” to denote the state of the public balance. All sorts of suggestions come up.

While I am sympathetic to the argument that we need a separate and effective language I also consider that communication is, in part, made effective by education.

I think we can lose the plot completely if we start inventing new terms for, say, the “deficit”, which will not communicate anything meaningful.

In those sort of cases, I think it is better to provide better education and better tools for comprehension rather than invent a new language for the sake of it.

Statement 2 Government spending adds to net financial assets in the non-government sector

Again a correct conclusion.

A common metaphor – the government is spending like a drunken sailor in port – is used all the time in the media and introduces anxiety into the public debate.

It allows those who have an ideological objection to government intervention to justify fiscal austerity programs that drive up unemployment and reduce our real incomes.

We support policies that make us worse off because the debate obscures the truth.

Some of the literature points to the fact that the term – spending – invokes the perception that something is spent or gone.

Government spending is, in fact, a flow of funds (net financial assets) to the non-government sector, which increases our incomes and saving, increases employment and increases the capacity of the non-government sector to risk manage the future (by increasing our saving).

In this case, a change in language might be helpful and still retain meaning.

We might use the term recurrent investment for government consumption spending and long-term investment instead of government capital spending.

But then again, using the term investment, might confuse the debate, given that investment has two meanings: (a) economists use it to describe productive capacity building; (b) the layperson thinks of it as the purchase of a financial asset.

But it is possible that the positive connotation that “investment” promotes would be useful.

Conclusion

A work in progress.

We will be interested in seeing whether you think terminology matters and what alternative terminology you might consider appropriate for the following concepts:

1. Budget balance

2. Budget deficit

3. Budget surplus

4. Public debt

5. Government spending

6. Government taxation

7. National income

8. Income support payments

9. Full employment

That should get things rolling ….

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2013 Bill Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Bill,

If you want to “penetrate the public psyche” you’ll have to keep it VASTLY shorter and simpler than the above article. The above is near 6,000 words. No member of the “public” will read anything that long. Chris Dillow actually criticised you (and Frances Coppola) recently for excess verbosity. Word search for “bill” here:

http://stumblingandmumbling.typepad.com/stumbling_and_mumbling/2013/10/what-i-learned-at-oxford.html

Your articles do contain plenty of interesting stuff, but the number of words per unit of interesting stuff is excessive, I think. Anyway, I’ve cut your 6,000 words down to just under 300 (which is probably TOO brief). Here goes…

The conventional wisdom is that there is a limit to the amount of stimulus government can implement when an economy is in recession. The reason, according to the conventional wisdom, is that governments have to go into debt to fund stimulus, and governments cannot go too far into debt.

That is actually nonsense in the case of a country that issues its own currency, because such a country can simply print money instead of borrow it. Indeed Keynes made the latter point about printing 80 years ago. And given the nonsense we get from advocates of the conventional wisdom, it’s no surprise they haven’t read or understood Keynes.

The reaction of conventional folk to the idea that government can print an economy out of a recession produces a response which is predictable to the point of tedium: they chant the words “inflation”, “Weimar”, “Mugabwe” and so on. Well the answer to that is that as long as the AMOUNT OF MONEY PRINTED AND SPENT is no so much as to cause excess demand then there won’t be any excess inflation. QED.

Another nonsensical element in the above conventional worry about government debt is that there is actually no sharp distinction between government debt and money (monetary base to be exact). That’s particularly true for debt that is near maturity and pays a near zero rate of interest. To illustrate, a chunk of government debt worth $X and which matures in a month’s time is simply a promise by government to pay the owner of the debt $X in a month’s time. Now what’s the difference between that “$X promise” and $X? Not much.

I’ve been trying phrases out in an attempt to come up with new metaphors and meanings on the various comment sections I argue on.

A few stand out.

(i) £100 of government spending always creates £100 of taxation for any positive tax rate. Each time, every time.

That is a very simple mathematic progression that is definitely true. You’ll note that I don’t say over what time frame. Inevitably that invites the retort of ‘why is there a deficit then’, to which you can respond ‘because somebody didn’t spend all their income in the budget period – in other words they saved some. Are you against saving?’.

The general trick here is to always start with government spending, and linearise the spending cycle based on that starting point. Because when you do that, you always end the linearisation at saving or taxation.

(ii) I’ve started calling the ‘Job Guarantee’ the ‘Job Alternative Guarantee’ – primarily to differentiate it from the aberration that UK’s Labour has in its proposed manifesto. The Job Alternative Guarantee is a permanent job offer to everybody, by the state, at the living wage, working for the public good.

‘Everybody should have a JAG’ is the tag line, which works here in the UK because a Jag is also a desirable car.

(iii) when anybody asks how you are going to ‘afford it’, respond by saying ‘by spending the money. Government spending funds itself.’

But you’ll note from the table above that our opponents have the pithy and succinct strap lines. It is those we need more than anything. Simple phrases that can be repeated that get the message across.

– Government spending always pays for itself.

– Everybody deserves a JAG

The other trick I’ve used to great effect is to reframe the question away from money completely and start talking in terms of stuff and people.

You’ll notice that any neo-liberal discussion always talks in terms of some currency symbol. As we know from the government’s point of view that is utterly irrelevant. What matters is how many tons of potential concrete there is spare in the economy and how to get it into a useful configuration given the spare labour on offer.

Forcing the debate into real terms is the ultimate re-framing trick IMV. Once you do that its very difficult to deny that we have a significant under-utilised surplus of capacity.

Dear Ralph (at 2013/11/05 at 19:53)

This is not a public marketing document – none of my blogs are. I am not a marketer or salesman.

These notes are aimed at organising my thoughts and presenting a body of work that academically-minded people will be able to learn from. Academically-minded doesn’t mean being an academic. It means that you are prepared to embrace detail as you acquire knowledge.

best wishes

bill

@Ralph Musgrave

Granted that Dr. Mitchell’s posts are more involved than the vast majority of reader’s are willing to accommodate but I’ve always thought that communicating these concepts to laymen were primarily our responsibility, those of us that blog and comment and submit op-eds to our local newspapers. In this sense the good doctor conducts primary research and then communicates that to us, which has we then transmit to the broader public as we can. A division of labor sort of thing.

Dear Bill

I agree that there is no intergenerational debt burden in a closed economy or in the world as a whole because every debt is also an asset to somebody else, but if a country has an open economy and keeps running current account deficits, then it will create a burden for posterity. One reason why a country runs current account deficits may be that its government continually has large budget deficits.

Regards. James

“but if a country has an open economy and keeps running current account deficits, then it will create a burden for posterity.”

How? The only promise in currency is that it is accepted as a tax credit in the state of issue.

There is no more promise to anybody holding a state’s financial assets than there is that gold will be worth something in the future, or for that matter tulip bulbs.

Which means that you need another motive as to why anybody would hold excessive foreign financial assets.

Neil,

Re your point (iii), you propose saying “Government spending funds itself” to anyone asking how we can afford JG. I think that’s too glib an answer, and I wouldn’t blame opponents of JG for not accepting that.

A better answer is to say that the wage costs of JG are pretty much already covered in that what people get on JG will in most cases not be much different to what they were getting on unemployment benefit. That would be particularly true if JG was part time, and there is a good case for making it part time: it leaves time during working hours to search for regular work.

As to the non-wage costs of JG (materials, equipment and permanent skilled labour) I think it’s best to admit that there is a cost there in the sense that the equipment and materials has to be knicked from the regular economy. However, since total numbers employed rises, then GDP ought to rise as well, unless JG jobs are disastrously unproductive. So in the latter sense, there is no “cost”.

Ben Johannson,

On the subject of op-eds submitted to local newspapers, I want to know why no MMTers get articles in the Financial Times and Wall Street Journal. Kenneth Rogoff, the world’s leading economic illiterate or should I say “advocate of austerity” regularly has articles in the FT.

Dear Neil

Let’s say that Ruritania has been running current account deficits for 40 years at the rate of 20 billion ruris per year and that before this 40-year period Ruritania had no foreign assets and that foreigners had no assets in Ruritania, then at the end of this 40-year period, Ruritanians owe 800 billion ruris to foreigners. If foreigners insist on getting repaid, then Ruritania will have to start running current account surpluses, that is, live below its means. If a country lives above its means in the present, as Ruritania did for 40 years, then it must live below its means some time in the future unless it will default.

You are really suggesting that a country with a large negative international investment position can default.

Regards. James

Following on from Neil Wilson’s comment, I think a missing category in your list is the role of taxation and its relationship to public funding. Virtually every journalist I have read gets this wrong. When discussing public finding, they invariably bring up the taxpayer and his/her relationship to the issue. It was most recently done in an interview in the Observer with Michael Manson, who does some excellent pro bono work but who is closing his office due to the government cuts to legal aid. Both he and the interviewer, Decca Aitkenhead, referred to the taxpayer. This irrelevant reference both waylaid and confused the argument regarding the public finding of legal aid to no one’s benefit.

While Aitkenhead has no economic training that I know of, she is not the only one to make this egregious error. Others are Heather Stewart, who supposedly knows some economics, Andrew Rawnsley, Polly Toynbee (whom you have mentioned previously), Nick Cohen, Stephanie Flanders (who has recently moved to JP Morgan from the BBC), and a number of others. This appears to be an almost insuperable hurdle. In discussions, I invariably get asked this question all the time – who is going to pay for it?.

One approach could involve introducing the concept of the collective character of society, something Thatcher denied existed. government can then be characterized as being collectively legitimated whereby the government carries out actions in “our name” and with our consent, such as it is, that is, with the consent of the collective. So, in a sense, government is “our” government and, therefore, the money it spends is “our” money. But it doesn’t follow from this that this money is that of the taxpayer. Rather, the relationship is more indirect and abstract. It is the collective’s money and the government its representative who acts in the name of the collective, for instance, by creating necessary monies for public programs.

Use of the term “collective” makes it sound like a hive with the inevitable pejorative consequences, but I don’t mean it that way. I have also, of necessity, simplified the issue. But I can’t write a treatise here.

@James Schipper

“… Ruritanians owe 800 billion ruris to foreigners. If foreigners insist on getting repaid …”

IIUC, this is where you go wrong. In what sense can any foreigner insist on being repaid anything? They have 800 billion ruris. That is their asset. If they want to be “repaid”, then they can spend them.

Ask the Chinese, they have a few trillion dollars in T-bills. I don’t think they are under any illusion that they can ask for them to “repaid”. But they can exchange them for other assets – physical or financial.

ideas in the MMT column

Sovereign issuer of currency is never at risk of default. The issuer of a currency cannot always meet any liabilities it incurs in that currency. ???

@James Schipper

“If foreigners insist on getting repaid, then Ruritania will have to start running current account surpluses, that is, live below its means.”

Why? They never had to run current account surpluses before, why at this time? Seems like it would be fairly straight forward to issue 800 billion in ruris in place of the 800 billion in ruris denominated securities if this is really necessary though probably this would be un-necessary as the foreigners probably don’t want the ruris to look at, they will probably want to buy goods manufactured by the Ruritanians economy.

You are right to think about how the use of language shapes our conceptions of how things work in an economy. For example, your use of the word ‘agent’ attached to government brought me up short, as I associate the word ‘agent’ with neoclassical theorizing. I had to stop and adjust for contextual meaning.

I am not trained in economic theory and I came to MMT via a winding road that included a cartoon on how banks work, and a campaign group advocating that governments spend via direct money creation rather than borrowing from the private sector. However, I was powerfully motivated to understand these topics because the crash in 2008 (lay people’s timing) came as complete and utter shock. It shocked me out of my complacency. So today, around 5 years later, when I read the terms above rather than thinking of deficits and surplus, and budget balances, I think of money flowing around a system. I have ceased to think of money, at a macroeconomic level, as having any intrinsic value beyond the role it plays in shaping the use of resources. Before I thought of money as something very concrete, as a stock, something you should collect or share out. I had absolutely no conception of money as ‘flow’. I think this switch – from only conceiving money as stock, to allowing for the conception of money as flow, or money as an ‘economic lubricant’ might be a key metaphorical shift. If you think of money as flow, rather than stock, inflation becomes a lot less scary, the notion of an economy running out of money becomes ludicrous, and where (or how) money originates within an economy becomes more pertinent.

But I am not sure how to use language to support this shift in conceptualization. Money as stock powerfully resonates with everyday usage of money.

Living in the US, I was always remined by my parents of the saying “only two things in life are certain, death and taxes” attributed to Benjamin Franklin. Growing up it was drilled into me government equaled taxes which were inescapable and oppresive, much like death. Even the J.M. Keynes saying “The avoidance of taxes is the only intellectual pursuit that carries any reward” or something to that effect was heard, which implies it is our duty and everyone cheats, some just do it better. To extricate cheating death and taxes from a psyche and maturing to the point of acceptance will be hard, indeed.

Bill;

You are going in exactly the right direction. There’s no good-magic spell that will break the bad-magic spell of neoliberal ideology with a single invocation. But we have to learn a lot more about framing and messaging to have any hope of getting through to people. And don’t worry about being too wordy. Please continue to emphasize being as thorough and comprehensive as you have time to be. Your job is to get it nailed down as tight as possible. It’s everyone’s job to make it flow.

I would rearrange the frame this way:

1. Budget balance

2. Budget deficit

3. Budget surplus

4. Public debt (“National Debt”)

All subsumed under a new primary category of “National Balance Sheet”, and a secondary, steering category I call “Budget Efficiency”. As in “what does each budget try to *accomplish*, and does it?” If it does, it’s efficient.

As for

5. Government spending

6. Government taxation

How about combining them as “Public Financial Engineering”?

7. National income = “The Pie We All Worked to Bake”

8. Income support payments = “Taking Care of Our Own” (via R Wray)

9. Full employment = “All Who Want to Contribute Should Have a Right To”.

You need something to counter “printing money.”

Professor Mitchell,

Based on own experience as a layman trying to gain an understanding of how our economic system really works vs the propaganda put forth by the ideologues on both sides in the US, I would be very cautious about creating another vocabulary to “frame” the discussion. I found the key concepts about the differences between a currency issuer and a currency user and the sector balance equations to be so strongly counter-intuitive that I suspect new terminology might make a challenging topic even more confusing.

If you have not already seen it, i found the presentation by Stephanie Kelton particularly clear.

http://www.fields.utoronto.ca/video-archive/static/2013/11/221-2524/mergedvideo.ogv

Best Regards,

Will Kanaley

The reason MMT is having such a tough time getting understood by the layperson is that most lay people never really understood economics in the first place. They have neither the time nor the inclination to learn because the subject is probably as difficult as they come. Learning requires major brain pain, and the fact that there are competing theories requiring philosophical analysis to divine their likelihood of becoming future knowledge just gives a sense that it’s too much effort until the academics are settled.

Changing the established formal terminology will only confuse laypeople further and they may actually begin to suspect deception, especially if ideologues with mainstream influences ‘help’ by pointing out the newly developing discrepancies in the language MMT uses.

While there is no hope of the masses ever attaining a first class detailed understanding of modern monetary theory, in my opinion, dispelling the most harmful public myths that mainstream and neoliberal thinking have nurtured is an attainable goal. Mainstream adherents can’t support any of these myths when directly questioned about their validity by someone who has even once heard the truth regardless of the forum.

A person doesn’t need a detailed understanding of MMT itself to ‘get’ the benefits of it’s wisdom. While the academic discourse should be left in the hands of the professionals, it is perfectly acceptable and healthy for laypeople armed with the salient facts to propagate them and demand their elected government representatives act in a manner consistent with them.

I have no formal education in economics and I’m certain this comes through in my comments; however as a layperson in relation to this field, I can tell you I could smell all of the neoliberal and mainstream BS as far back as it goes. Without the economics background it was difficult to put into words for much of a discussion over pints on Friday with my buds but I can assure you most had the same sense that we were being spun on major life altering points. It was only the types who studied commerce at university who suspiciously assured us of the validity of the mainstream mantras using the eloquent language they had learned.

The instant I heard the MMT take on where all the money comes from and how government can’t run out, I read the article several times just to be sure I didn’t misread anything; I recognized MMT as likely representing a more accurate perspective than we were hearing daily on the news. This inspired me to learn all I could about MMT with the time I have available.

While I have found your blog and the UMKC one most helpful Bill, I can’t say it’s been easy and I don’t think many people would pursue this because of the time involved and because most still don’t see how they may make a difference in the long run through their collective voice that politicians must eventually heed.

Perhaps MMT mantras paralleling and countering the myth mantras can be developed and every now and then a post can be dedicated to them. I’m sure they will conquer eventually!

Without a 1-page preceding synopsis, this isn’t going anywhere with most of our thousands of distinct audiences.

Already, various national “industry code” classification systems all list over 2000 distinct professions that citizens can be narrowly trained in. For good or bad, those are the audiences we must deal with.

http://www.census.gov/eos/www/naics/history/history.html

To speak to all those audiences at once, requires a level of summary not even approached here yet, Bill.

When you’re done, please consider this progression.

1) A one sentence summary. (of the Desired Outcome; e.g., an electorate able to explore a growing Policy Space with adequately growing Policy Agility?)

2) A one paragraph summary, of context. (e.g. no one could steer a Model-T with reins or a lever, so they all quit arguing against the novel “steering wheel”)

3) A one page summary of policy formation methods, in response to changing context. (describe MMT as a “steering wheel” mechanism; it works; leave it at that)

4) A long blog, with many of the known, context-specific, details.

(to borrow from racing; all the details about choosing & executing “lines” through new obstacle courses; once we have a steering wheel)

Why? That’s how to accelerate recruitment of unpredictably diverse audiences – to a neglected topic they must nevertheless come to understand. Step by step.

e.g., http://voices.washingtonpost.com/class-struggle/2010/04/unlike_many_escalante_believed.html

It’s hard to find, but somewhere in Escalante’s writing is his own statement, about teaching awareness, context, application and THEN methods & tactics (similar to the above, 4 steps; he’d have his classes skim their entire book in one day – just to orient [1st point is that calculus is a steering tool, for doing all kinds of awesome things]; then they’d read all the chapter summaries the next day [how the tool was conceptually used, on different, awesome challenges], THEN they’d skim one chapter, to understand example challenges. And only THEN would they actually study that chapter, and go through the exercises – actually practicing use of the “steering wheel”; & so one, for each chapter).

His lesson about developing situational awareness first, as a prelude to institutional responsiveness – albeit in another setting – are useful. Seems attractive to consider that macro-economics to must examine how to get common sense currency operations more consistently appreciated by the thousands of professions making up a modern electorate.

http://reason.com/archives/2002/07/01/stand-and-deliver-revisited/print

Electorates have a macro-context to navigate. Educating the students is hard enough, but it’s just a start. The entire shaping process is easier if it is ALL coordinated, into a coherent campaign strategy for reaching a simple, consensus Desired Outcome … while leaving infinite room for local adjustments.

MMT has done a damn good job in Blogland over the past few years. Much of it due to Bill.

i would still like to see a joint attack by the all the modern money bloggers and the post Keynesians to move things forward from here.

Fat chance of an accommodation but that’s my opinion.

Neil, I very much agree with the concept of arguing based on the ‘real world’. That’s the answer to the ‘we don’t have the money’ refrain. Long ago my learning process started with the question: what exactly does that mean? Given that there are no money mines or money trees.

You can ask ‘Does it make sense to have huge numbers of people who want to work and produce something of value, sitting around doing nothing?’. That is a clear sign that your ‘system’ isn’t working. People need to realize that these things are not ordained by Heaven (or a lack of ‘money’), but are the result of choices we are making.

An example from another area in which I have an interest, nuclear power. Russia is currently offering complete financing for the construction, ownership and operation of nuclear power plants (Build-Own-Operate) abroad. People ask ‘how can they afford this’, ‘they are going into debt’, etc. But, since Russia has the complete supply chain within Russia, they can always generate whatever rubles are required. The only limitation are the real resources, steel, engineers, etc. What matters is whether this is a good investment in terms of the goods and services that the client will provide in return. They obviously have confidence that they will get something worth their investment of real resources, people, time, back from the Turks, Vietnamese, etc. ‘Money’ is not the issue.

The government is the people’s agent, and they have authorized it to issue money so they have a convenient way of buying things and paying their taxes. Taxes represent reimbursement for infrastructure, education, research, and defense projects government has undertaken on behalf of the people. If the economy is so weak that people cannot find employment or resources are being underutilized, the government either lowers taxes or issues more money. If the economy is so strong that production of goods and services cannot meet demand, the government increases taxes or stops issuing money. That’s how the economy is stabilized.

This admittedly oversimplified paragraph overlooks many salient points about the economy, but can be understood by almost anyone. It doesn’t contain the words debt, deficit, MMT, GDP, neoliberal, balance, trade, foreign, flows, stocks, etc. It doesn’t address the subtleties of the government vs. the Fed. It doesn’t address the fact that other entities can create money through issuing debt. It doesn’t address inequality. The “national debt” is not a debt to anyone. It is just an accounting of the net accumulation of money the government has issued over time. It may fluctuate up and down, but it is not something that needs to be paid off or compared to GDP. To think of it that way is to think that somehow football teams need to pay back the scores they have run up in a game. These are things that Joe and Jane voter don’t need to know. It’s for politicians, economists, bankers, and bloggers to argue about and formulate policies that work.

If the misinformation. propaganda and jargon that now fill the national conversation can be countered by simple concepts repeated over and over again, on the internet, on talk radio, and anywhere people gather it would eventually gain some traction among lay voters. As long as special interests can continue to muddy the waters there won’t be much progress. Economic ideology currently being practiced by many, without being backed by facts and truth, is a lot like religion. It will continue to propagate as long as it gives people the feeling that things are going to be okay. It’s all a fools errand. And it needs to be countered by simplified concepts that lay people can understand.

James Schipper,did you actually read this blog post? As you are a frequent commenter here have you actually read Bill’s other posts especially regarding the difference between an internal government deficit written in that governments currency and an external deficit written in a foreign currency?

You state that your Ruritania has a deficit written in ruris. They will have no problem funding that deficit regardless of who has a call on it.

If that deficit is written in a foreign currency then they may have a problem. Bill has made this point many times especially when referring to the EMU.

Sometimes you refer to the private sector as the” non-government sector”. ” Private sector” or “individuals and businesses” sounds better in my opinion. “Non-government sector” sounds like it lumps all the economic activities of individuals and businesses into a category somewhat inferior to the government sector to me.

Regarding the complaint that Bill’s posts are too long I suggest that the complainers develop the skills of scan/skip/reread(if necessary). This skill set is essential for a lot of written work,not just in economics.

I am no economist and I usually skip a lot of the technical stuff. Fortunately Bill avoids using the self conscious and self aggrandizing jargon that is so beloved by some economics writers.

I am simply grateful that we have in Australia somebody who is prepared to put in the time and effort to educate laymen/women on economic matters.

Some may have missed what is implicit in the simple paragraph I presented in the prior post and which is repeated below followed by some of the implicit assumptions.

“The government is the people’s agent, and they have authorized it to issue money so they have a convenient way of buying things and paying their taxes. Taxes represent reimbursement for infrastructure, education, research, and defense projects government has undertaken on behalf of the people. If the economy is so weak that people cannot find employment or resources are being underutilized, the government either lowers taxes or issues more money. If the economy is so strong that production of goods and services cannot meet demand, the government increases taxes or stops issuing money. That’s how the economy is stabilized.”

Implicit in the above description of the economy is the fact the government is the sole issuer of money, taxes are not collected and then used, but instead the government can spend for what has been legislated to be done and then collect taxes after the fact to reflect what goods and services the people have received. In times of a weak economy the government can reduce taxes and defer reimbursement, or in times of an overheating economy, the government can accumulate taxes it will need for future projects to take some steam out of the economy.

I suggest that we emphasize the savings side of the government debt and deficit. Treasury bonds are savings accounts. Cash and bank reserves are checking accounts. Always turn the discussion from the national debt to the corresponding private savings.

The best bet for MMT is to prepare the ground for the public outcry as the shortage of middle class savings becomes a major issue. Americans have bought into an ownership society based on volatile private savings held in stock market funds which have lost 50% of their value twice in the last 12 years. If (when, in my opinion) that happens again, the middle class will be very receptive to the idea of the government helping them get back their savings…

Political problems require a political solution. The only way MMT will gain acceptance is if it becomes part of a political movement. If you wish “language” to flourish and evolve, replace the ruling class.

I’ve become a big proponent of MMT since I retired 5 years ago and have even written a few things for a small group of friends. But like most other MMT’ers I run afoul of the usual intuitions that people have. A few months ago it occurred to me that those intuitions were mostly accurate when we were all on the gold standard, so I decided to create a narrative that started with the premise that we were still there. First I explored the problems that occurred under that system. Then I added a thought experiment: suppose the government discovered a virtually unlimited gold mine on its own land. I explored how that would change the scenario for the government. There are lots of details of course, but you quickly see that the debt is no longer an issue (although you wouldn’t necessarily want to just pay it all off with your new found gold for various reasons). Then I explored the different ways that we could put some of the unlimited supply of gold-backed money into circulation. That leads to discussions about spending versus transfer payments versus lending money into the economy. The last of these would in effect force the private sector to take on ever-increasing amounts of debt (in order to cover the interest charges); which is obviously crazy when there is an unlimited amount of gold available. And of course that is effectively what we do today without sufficiently sized government deficits. But you can’t just give it all away either because you would effectively remove any incentive for people to provide labor. The whole discussion gets too complicated to include here, but I think you get the idea. The final step is get to the realization that a fiat money system is largely equivalent to this situation because the government has an infinite supply of money at its disposal; at least many of the same policy decisions seem to apply. My paper keeps growing as I add more ideas, so it may be that there is no simple way to really make the case effectively, but I can’t shake the feeling that we need to start with a discussion that gets people nodding their heads up and down in agreement rather than shaking them back and forth in doubt and then lead them step by step to MMT.

Bravo Prof. Mitchell , thanks for this post and your effort to make simple what itsn´t evident. MMT is to economics as quantum theory to physics. Meanwhile here in Spain people suffer the ludicrous economic policy implemented by conservatives ( now) and “socialists” (before) , both in love with austerity while unemployment is climbing to 26% . http://www.datosmacro.com/paro/espana

What about considering a much more condensed approach designed with a hook for Public consumption ?

For example, focus on say, only three of Professor Mitchel’s points.

1. Government spending

2. Full employment

3. Government taxation

The point that I am attempting to make is that the message needs to get out there using words, concepts etc. that are relative and familiar to the great unwashed masses maps of the world. Call it marketing or perhaps an advertising approach, regardless, the goal is to get the message out to the people. The academic argument is a distinctly different issue that can stand on it’s own.

I believe that George Lakoff has done some robust research in this area, which may well help?

Just getting the message out about the inherent characteristics of fiat currencies, which can lead to full employment, more public services and a tax reduction is something that is marketable. It may sound crass, however, I don’t think it’s possible to layout the whole argument and I don’t think it’s neccessary.

Acorn [Wednesday, November 6, 2013 at 0:4] pointed out a serious typo in the tabular presentation. Against the left-hand column’s statement “Sovereign issuer of currency is at risk of default”, the following is stated: “Sovereign issuer of currency is never at risk of default. The issuer of a currency CANNOT [ my caps] always meet any liabilities it incurs in that currency”.

Printing money makes about as much sense as printing every web page on the internet.

Much easier to just press a few keys on a keyboard and then look at the screen.

‘You need something to counter “printing money.”‘

Do you? Or do you just need to embrace it and turn it around as a positive thing.

“Yeah we create new money, because that way we don’t have to confiscate the old money from those who prefer to stick under their mattress or leave it to gather dust in bank vaults.”

“”Non-government sector” sounds like it lumps all the economic activities of individuals and businesses into a category somewhat inferior to the government sector to me.”

It also includes the external sector. Non-government sector generally refers to the domestic private sector plus the external sector (non-domestic private and public sectors).

Not mine at all but unfortunately don’t have appropriate attribution:

“Budget deficits create private wealth.”

“Budget surpluses destroy private wealth.”

“Budget deficits increase private savings.”

“Coca-Cola doesn’t run out of coke. The US Government doesn’t run out of dollars.”

With respect to “Broad principles and terminology” above, one criticism of progressives is “More government is their only solution.” The above does nothing to dispel that criticism. Furthermore, I take a bit of issue with the statement “Mass unemployment is a sign the budget deficit is too small.” Especially given the mantra that the budget deficit is exogenous. It may be just as likely that “Mass unemployment is a sign that government spending is misallocated.” You know as well as I that taking 300 Billion from making bombs to provide for a JG may result in a similar or equal budget deficit but provide for full employment. But it does no good to quibble. Thank you for everything you do.

@Neil at 22:20: one motive for holding excessive foreign financial assets may be to keep your own currency undervalued wrt to the foreign currency in order to enable a large manufacturing base of employment and elevate exports.

And while technically correct that a sovereign gov’t can never run out of its own currency it is true that a large percentage of savings in the currency of issue held by foreigners in domestic securities will enable a lack of savings among workers, create issues with velocity and exacerbate inequality. And if said foreign entities ever decided all of a sudden they had no further need to save in the foreign currency it can and has created problems for the domestic government, even if said problems could be solved thru greater awareness. That is, as this blog regularly demonstrates, a commodity in short supply.

Bill –

Your explanation of why the claim Budget deficits drive up interest rates because they compete for scarce private saving is false fails to mention that budget deficits drive up interest rates because the central bank sets interest rates to schieve a target objective. Whether that objective is based on inflation, employment or growth, the public sector is competing for resources with the private sector, so (except in deep recessions) the public sector using more resources means the private sector has to use less resources. Raising interest rates is the way to reduce the private sector’s resurce use.

And on your response to the government spending is inflationary claim, your first sentence All spending (private or public) carries an inflation risk is true. Your second sentence Government spending is not inflationary while ever real resources are idle (ie. There is unemployment) is false, as Australia proved in 2007. And indeed you went on to state the reason why it is false: All spending is inflationary if it drives nominal aggregate demand faster than the real capacity of the economy to absorb it.

“And if said foreign entities ever decided all of a sudden they had no further need to save in the foreign currency it can and has created problems for the domestic government,”

Not without creating problems for itself.

The reason that they are saving in a foreign currency is so that they can shift more exports than just real exchange would allow. That is the purpose of ‘liquidity measures’.

It is vitally important that we change the economic model and stop seeing the external sector as some sort of Deus Ex Machina. It is not. It is a collection of other economies with the same constraints and feedback loops as yours.

In fact I’d go as far as to say that we should stop using the ‘external sector’ and instead move to a ‘whole world’ model based on economy A, B and C all of which interact.

Then you can see that a policy response in C regarding A’s currency will have a feedback effect on C’s real economy via A’s real transactions with C.

There is only one planet undertaking human economic transactions.

There is a need to understand why there is a frantic fear of population about government deficits.

Yugoslavia was destroyed by government debt manipulation from the countries that wanted it destroyed/ changed from kommunist system into capitalist system. There are many examples in history how countries were manipulated and hurt by using government debt by outside agents. Greece and rest of the PIIGS is a clear example of outside players influencing whole country’s well being.

But that applys only to the non-sovereign currencies, even tough Yugoslavian currency was free floating but had debts in foreign currencies due to the need for oil and car imports.

Not to have large government debts in foreign currencies is very important in antagonistic environment which itself is created by imbalances of government debts. That is where frantic fears of population about government debts come from, even tough it applys to the debt in foreign currency.

Government spending= government issuing= government creation. It is using the values from the principles described by Bill.

I think also that it is important to develop narations that explains real situation on the ground, narations that will reeducate from mainstream naratives and also explains the need for money growth.

I use such naration as the starting point.

Imagine an economy with fixed money supply, fixed population and one corporation.

In such situation all income have to be spent in order for all production to be cleared /sold. Cost of production is total income and that income has to be again total cost of production. It is in equilibrium where everyone is employed and fed.

If owner of the corporation saves(capital accumulation) money after the goods are sold, there will be not enough to cover for all costs of production and there will be underproduction and unemployment.

If workers decide to save for later consumption, all products can not be sold and it will cause underproduction again and unemployment. Through multiple cycles it will come to reduction in employment, in incomes and savings. In fixed money supply, economy crashes if people decide to save.

In order to save and have full production at the same time, savings have to become credits to corporation/ corporate debt. And debt carries the interest rate which is also bringing reduced production through lack of spending on production costs.

But populations aren’t fixed in real world, where wil additional production that requiers additional costs come from in order to satisfy growing population? It can come only from additional money added to the economy. Credits/savings from other sources have to arrive, hence banks create credit to increase production for increased population.