I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

We are in trouble – squirrels are falling down holes

Today we explore the problem of squirrels falling down holes. The exact number and size of the holes is to be determined – there is some disagreement. Who the squirrels are is also somewhat confused. But some thorough analysis should get us through this difficult task. Suffice to say, I have been reading the World financial press again … as I do against my own better judgement on a daily basis … and have done for the last too many years.

A lead article in the New York Times – Wave of Debt Payments Facing U.S. Government on November 23, 2009 quoted one William H. Gross who thinks he has pearls of wisdom that he wants us to share:

What a good country or a good squirrel should be doing is stashing away nuts for the winter. The United States is not only not saving nuts, it’s eating the ones left over from the last winter.

After that, I conclude that perhaps Gross should stick to stamp collecting rather than to engage in furthering the public ignorance about how the monetary system operates. Being successful in managing financial assets does not mean that a person understands the operational dimensions of the monetary system and the way fiscal policy operates.

Last time I looked the US Budget balance (12 months to September 2009) was -10.0 per cent of GDP, the Current Account Balance was -3.8 per cent of GDP, which means the domestic private sector must be saving at a rate of 6.3 per cent of GDP over the last 12 months.

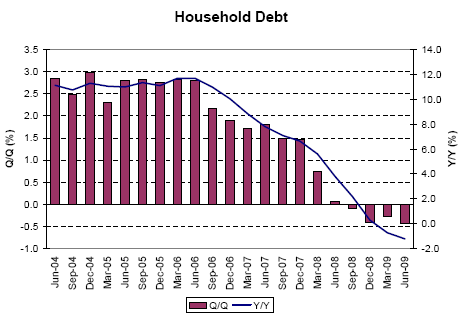

The following graph is taken from the excellent Valance Chart pack and shows quarterly (purple bars) and annual changes (blue line) in US Household debt. Clearly the payback has started.

So the squirrels who have to save are doing that and also paying back past excesses although the hangover will be profound. Given that the US Current Account is not heading into surplus anytime soon, the only way the squirrels can achieve their aims of building up some “nuts” for the future is if the big nut provider pumps more into circulation than they take out.

So net public spending is required to “finance” the household saving and debt reduction process that is now on-going and essential for recovery. Modern monetary theory (MMT) uses the term “finance” in the sense that private (and hence national) saving is a function of aggregate income growth (GDP growth).

Income growth, in turn, is dependent on aggregate demand (spending) growth. If spending growth falters, then output and income growth falters and the capacity to save by the private sector is compromised.

So the budget deficits (net public spending) are maintaining growth in demand to keep income growing and hence support private saving. That is the way the real squirrel world operates.

In the case of the UK, which still hasn’t seen the light of positive GDP growth (after 6 consecutive quarters) it is clear that the budget deficit is not large enough and is failing to offset the contractions in aggregate demand. That is very clear and is never addressed by the budget terrorists who never connect things up in a consistent way.

Any notion that the big nut provider will ever run out of nuts is ludicrous and incorrect.

I was talking to one of my PhD students today and the conversation – initially was about whether the student should get involved with continental philosophers (Foucault, Derrider etc). My advice was that is a hole that any unwary student can fall down and get lost down, almost forever.

But then we talked about how the deficit terrorists talk in slogans (for example, “debt is socialism”; “drowning in debt”; “not saving enough nuts”) but exploit the ignorance of the populace (and probably their own) in failing to connect all their claims into a stock-flow consistent, accounting framework.

When challenged to do so they baulk and chant even more virulent slogans – but by this time they are usually personal – and will almost inevitably include a reference to a “person’s obvious communist leanings” and the like.

For example, they say they want private sector debt to fall and the private sector to increase their savings. Okay, so do I. Then they say they want public debt to fall as well. But of-course they would never broach a change in legislation or custom that voluntarily constrains governments to issue debt to match $-for-$ their net spending.

After all, they claim that imposes a fiscal discipline on dangerous inflationary public spending. Debt is bad so governments will try to avoid the public ignomy associated with it.

So what they must be saying and they do is that they also want the government budget to be in surplus.

But if there is a current account deficit running (whether you like that or not is not the point) – then their demands are mutually inconsistent.

If the private sector was to increase saving (with a CAD running) and nothing else accompanied that change then aggregate demand would fall, output and employment would fall, unemployment would rise, and the budget would be pushed via the automatic stabilisers into deficit. The income decline would stop when the deficit matched the desired private saving plus the CAD.

So the terrorists ambitions would be foiled.

Alternatively, the government might realise that they do not want to end up with a bad deficit (with rising unemployment and stagnation) and so they match the desired leakages (private saving intentions) with an increasing budget deficit. Again, the budget ends up matching the desired private saving plus the CAD but the economy is in good shape.

But if you confronted the anti-deficit crew with this totally comprehensible and consistent understanding of the way the national accounts work together and the economic adjustments (income) that ensure the stock-flow consistency they would just shriek some more slogans.

Anyway, talking off holes … We read often about there being a “hole in the fiscal bucket” despite the fact that modern monetary theory allows us to understand that there is no bucket!

In the November 19th edction of the The Economist, Jon Berkeley writes about Dealing with America’s fiscal hole.

The Economist article says:

FOR years America’s fiscal problems had a surreal quality. No one disputed that an ageing population and health-care inflation could bust the budget, but that prospect was decades away and procrastination seemed painless. No longer. A giant hole has opened in the budget because of stimulus, bail-outs and a recession that has savaged economic growth and tax revenue. On current policies the publicly held federal debt, 41% of GDP last year, will double in the next decade … Total government debt will move well above the G20 average. In a few years the AAA rating of Treasury bonds, the world’s most important security, could be in jeopardy.

No-one? Not a single person? All those who understand MMT never considered the issue of the ageing population to be financial. So there were at least 18 of us! (what is the latest count anyway?). We conduct a head count at next week’s CofFEE Conference. I jest. Sorry. I know the ageing population is a serious issue.

But the serious issues are political in nature because I cannot foresee us running out of titanium for the hip replacements. The younger generations might all instruct their governments not to make the outlays necessary to provide first-class health care. Certainly in the US, the political system already ensures the most disadvantaged Americans miss out of the health care that other richer citizens have access to.

So in liueu of the nation (World) running out of real health care resources, all the allocation issues will be political. The US or any sovereign government will be able to afford whatever there is for sale at any point in the future.

Further, the AAA rating of US Government debt is irrelevant. Japan proved that when the ratings agencies played their games on them some years ago and significantly “downgraded” their public debt. It didn’t stop Japan running huge deficits, selling huge amounts of debt into the markets and keeping interest rates at zero and inflation negative or zero.

The ratings agencies should be legislated out of business which would force private firms to better appraise the debt that is available in the private capital markets. I cover that issue in this blog – Ratings agencies and higher interest rates

Anyway, now we have this giant hole. I was curious. I consulted the definition.

A hole is:

* an opening into or through something

* one playing period (from tee to green) on a golf course; “he played 18 holes”

* an unoccupied space

* a depression hollowed out of solid matter

* a fault; “he shot holes in my argument”

Hmmm, tricky. What exactly is a budget deficit first?

Every day the government is crediting private bank accounts (directly or via cheque issuance) to pursue its socio-economic program. Each day also, they collect tax revenue by debiting private bank accounts (or writing receipts over counters to payees). The tax revenue is accounted for but “doesn’t go anywhere” in a physical sense.

A deficit arises when the spending exceeds the revenue and the net result is an addition of net financial assets (bank reserves). In achieving this outcome, the government hopes that its spending will boost aggregate demand (“finance” the leakages from the income-expenditure system), and, hence maintain high levels of employment and material prosperity.

The only hole I can see is one that needs to be filled. That is the spending gap – the leakages from the income-expenditure system – that are created when there is a CAD and/or a desire by the private sector to save.

Budget deficits should aim to fill that hole in and not allow aggregate demand to “fall through it”, which would lead to income and employment collapses.

If budget deficits are underwriting income growth, then workers can enjoying secure employment and achieve their saving desires – which will enable them, should they wish to use purchase some golf clubs and play a few “holes” in their leisure moments. Sounds good.

I won’t go on except to say that MMT shoots “holes” in the mainstream economic theory because the latter is not stock-flow consistent.

The Economist article then says:

Uncertainty over how taxes may be raised to shrink deficits may already be weighing on business confidence. Worries about inflation or default could start to push up interest rates. Eventually, private investment will be crowded out.

So you note that the crowding out argument is not the typical textbook ploy based on either loanable funds theory (finite savings being eaten up by government debt issuance) or liquidity preference arguments (money demanders need higher rates to hold more money). Both of these textbook arguments are plainly false and reflect an ignorance of the operational reality of the monetary system.

This time the crowding out is based on a fear of inflation (so long debt rates rise to reflect the risk of holding for long periods) or default.

When has the US Government ever defaulted? Never.

What is the rate of capacity utilisation in the US at present? Answer: around 70 per cent if lucky.

What is the broad labour underutilisation rate in the US at present? Answer: around 17.2 per cent.

Does this sound like the US is going to be short of real resources and productive capacity any time soon? Not to me. And by the time the economy is growing fast again and private spending returns the deficit will be coming down via the automatic stabilisers.

So this commentary from The Economist is just fuelling mindless paranoia.

The Economist then gets wise:

Barack Obama and Congress can pre-empt such corrosive uncertainty with a plan to reduce the deficit now … America’s deficit problem is in essence a spending problem, so spending must bear the brunt of adjustment.

Yes, it is like those squirrels again. The deficit is a spending problem. But it is the failure of private spending that has demanded such large fiscal responses (and you have to ignore the TARP component which the deficit terrorists like to add into the conventional fiscal measure to make it look worse).

Spending has to bear the brunt of adjustment. Private investment has to increase before any realistic reduction in the deficit will be possible.

Anyway, The Economist article just got more puerile as it went on and I decided to seek solace in the New York Times. Big mistake.

A lead article in the November 23, 2009 edition (the one with the squirrel’s quote) said that:

The United States government is financing its more than trillion-dollar-a-year borrowing with i.o.u.’s on terms that seem too good to be true.

But that happy situation, aided by ultralow interest rates, may not last much longer.

Treasury officials now face a trifecta of headaches: a mountain of new debt, a balloon of short-term borrowings that come due in the months ahead, and interest rates that are sure to climb back to normal as soon as the Federal Reserve decides that the emergency has passed.

Even as Treasury officials are racing to lock in today’s low rates by exchanging short-term borrowings for long-term bonds, the government faces a payment shock similar to those that sent legions of overstretched homeowners into default on their mortgages.

But, sir, the US government, which issues the currency, is not remotely like a household, which uses the currency of issue. The US government faces no payment shock at all, unless of-course the keyboard operators employed by the Treasury Department have RSI or something that gives them pain when they are typing (very big) dollar numbers into spreadsheets and bank account ledgers.

And note that our giant hole is now also a mountain. I guess in a stock-flow sense, if there is a hole the dirt has to have been accumulated somewhere.

The NYT writer continued:

The potential for rapidly escalating interest payouts is just one of the wrenching challenges facing the United States after decades of living beyond its means … But there is little doubt that the United States’ long-term budget crisis is becoming too big to postpone.

Americans now have to climb out of two deep holes: as debt-loaded consumers, whose personal wealth sank along with housing and stock prices; and as taxpayers, whose government debt has almost doubled in the last two years alone, just as costs tied to benefits for retiring baby boomers are set to explode.

Just when we were thinking there was one giant hole that the US was falling through, we now learn there are actually “two deep holes”. I suppose deep and giant are similar and the NYT just likes to run with a bit of modest understatement compared to the very English Economist Magazine.

To get matters into perspective – the US government will make the interest payments in exactly the same way it spends generally. Some electronic entries will appear in the banking system somewhere. There is no special onerous process called interest payments unless the keyboard operators have some kinky customs and self-flagellate to reflect their guilt on behalf of the government as they make their keyboard entries making the interest payments. Last time I heard they do not do that.

Certainly, the US private sector (consumers and households) have to sort out their balance sheets. That is clear and necessary. But as taxpayers all they have to do is ensure they pay on time.

They are not responsible for the public debt. They will never have to “pay it back” in the form of higher taxes. As the economy grows as the stimulus packages restore some demand growth and confidence to the US economy, tax revenue will rise. That is because the more people will be employed and earnings will be up.

It might be (as occurred in the 1990s) that tax revenue will outstrip the debt servicing payments, especially if the Fed keeps rates low for longer than they will, and the debt will also fall, without any necessary cut-backs in discretionary spending.

That is not to say I support the composition of the spending side of the US budget. Clearly I do not. There is a totally insufficient spending focus on creating jobs, especially for the unemployed and too much emphasis on helping the top-end-of-town stay there.

Anyway, the NYT articles rambles on like that. Intergenerational disasters in health and aged care. Yawn. Blowouts when the Federal Reserves restores interest rates to normal. Yawn. What is normal anyway? No-one to buy the debt despite all the bond auctions being “solid”. Yawn.

“all that new government debt is likely to put more upward pressure on interest rates”. Yawn.

“Inflation, higher interest rate and rollover risk should be the primary concerns”. Yawn.

And so it went.

I had more fun today while I was looking for some data. I stumbled across one of the more hysterical sites out there and I noted a link Example of Socialism. I won’t link to the site itself because I don’t feel like making them feel like they are popular. That fact that I was duped into visiting the site in search of some information is enough.

But an “example of socialism” – that would be scary. Was this a www-site that pretended to be promoting deficit terrorism but was really a socialist front to beguile us into clicking on the link and risking falling prey to their evil mantra? These questions rushed through my mind. But I clicked. I couldn’t help it.

Anyway, if you are curious about what might be the steps to socialism then you will learn that the “example” is in fact the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Lifeline Program to help guarantee Universal Service in the US to low-income families who qualify under Federal poverty guidelines. Think about how useful a telephone is to you. Well it is probably that useful to everyone to help keep tabs on family and friends.

Socialism requires at the very least the nationalisation of all means of production. A modest program that allows kids to telephone their parents in time of emergency etc is a way removed from that socio-economic change.

I wonder why Americans are so hung up about socialism anyway. In all the places I have travelled it is the US that is the most fearful. Perhaps they don’t trust their so-called system of “wealth generation”, which by any measure has left a signficant proportion of the population behind.

Here is an essay question I have created based upon another quote on the site with the link to “example of socialism”.

Critically analyse the following statement which circulates throughout the Internet.

…all dollars come from the people. Where do … [you] … think Coca-Cola gets the money to pay its taxes, Exxon gets its money to pay the Exxon Valdez fines, Denny’s gets the money to pay its Justice Department fines, or even Microsoft gets the money to defend itself? It all ultimately can come from only one place, and that’s from individuals.

For full marks, make sure you discuss in your answer how inflationary budget deficits are and how they also push up interest rates and destroy the entrepreneurial ambitions of good people all over the world. Ensure you introduce some animals into the analysis (perhaps a few squirrels) and provide exact engineering specifications for the diabolical holes that our national governments are about to fall down.

Also include a thorough analysis of how net public spending is equivalent to socialism and an invasion of our basic freedoms. Integrate terminology such as “public debt is cancer” and “public debt is communism” into your answers.

I urge you to use Mankiw’s Principle of Economics as your primary and sole source and plagiarism is encouraged.

Good luck!

Conclusion

I think that is enough for now.

It is time to have some food … I think I am becoming weak.

Youtube

If you want smaller snippets (question by question) of the modern monetary interviews I posted yesterday, they are now available (first 10 questions) on Youtube.

Just type in Modern Monetary Theory and you should find them. We are working to refine the quality in the coming weeks and will post the rest of the material once that is accomplished.

We will also have a lot of videos from next week’s CofFEE conference.

Hi Bill

You sure know a lot about squirrels for a guy from Australia! Sorry I can’t be part of your headcount next week.

Thought I’d reprint what I circulated in a private email yesterday regarding the NYT article’s warnings that interest on the debt could rise to $700B.

If nominal GDP grows from 14trillion now by 6% each year (the post war trend), total GDP in 2019=25.1T

If debt service is 700B in 2019 as the article “warns,” then this is 700/25100 = 2.8% of GDP, which is less than during the Reagan years through the mid-1990s. And btw, if GDP grows 5%, then we’re at 3.1% debt service.

Also, CBO estimates assume the Fed will put short-term rates up to nominal GDP growth, even a bit higher, which is driving this estimate of debt service. They will find that they won’t be able to sustain rates that high unless household debt falls significantly to avoid a large increase in their debt service [which likely requires more govt debt in order to reduce household debt].

Haven’t looked to see if they are using the right measure of debt service (that is, whether part of the 700B is for the trust funds). But the 202B for current is correct . . . though again, it was 250B in 2007.

Best,

Scott

Great title! There are two questions I’ve been meaning to ask…

“Income growth, in turn, is dependent on aggregate demand (spending) growth. If spending growth falters, then output and income growth falters and the capacity to save by the private sector is compromised.”

First, do you know whether there is any lag in the statistics (either due to the way things are measured or due to possible real-life lag effects) between an increase in the non-government sector’s attempted savings rate and the resulting fall in income as reflected in GDP?

For example, does the recent peak in the US personal savings rate of around 6% reflect the desired savings rate or simply what was achieved as a function of the size of the government deficit (and CAD)? I’d guess the latter more likely (fitting MMT theory) and that the fall in GDP was a function of the extra attempted savings, but wanted to check regarding measurement or economic lags.

“So net public spending is required to “finance” the household saving and debt reduction process that is now on-going and essential for recovery. Modern monetary theory (MMT) uses the term “finance” in the sense that private (and hence national) saving is a function of aggregate income growth (GDP growth).”

Second, to what extent have MMT folks measured or modeled the dynamic feedback *effects* of government financing of the debt reduction process? Specifically, I have in the past (when worrying about Irving Fisher-style debt deflation dynamics) assumed that the end of credit bubbles (e.g., in housing) would reveal them for the unsustainable foolishness that they were, leading to a change in psychology to pay down credit cards, loans, etc, and that any extra income given to debtors by government would simply be used to accelerate debt repayment rather than adding to their spending. (Though of course giving money to *unemployed* debtors would still support their core spending, which I know is crucial!)

I do understand that a fall in discretionary spending (cutting back on non-necessities) as folks paid down debt faster could still be offset at an aggregate level by additional government-funding spending, so I’m not making a case against MMT prescriptions. But I am curious whether you look at network feedback style effects that result from government actions (e.g., in Japan)… i.e., in effect, might not the private sector escalate its savings target as a RESULT of the government sector accommodating the desire, and what are the impacts if so?

Such escalation might not matter much in reality… but taken to an implausible extreme (but for the sake of illustration), the government might effectively pay off all private debt via transfers to debtors. I guess then you just have a lot of private debt (bank loans, bonds, etc) replaced with government liabilities (right?)… and you’ve eliminated many private debt service obligations. This may be inflationary but MMT says if so you raise taxes or reduce government spending… It’s potentially politically inflammatory for private balance sheets to change in this way, but the theory (as I work through it, and ignoring questions about practical limitations for now) seems solid and gives me increasing cause for optimism! (Still curious regarding MMT studies of dynamic feedback effect, though).

Bill – am wondering if there is a short sharp point form ‘frameworks’ or skeleton statement of MMT somewheres? I.e. no explanations or justifications, just sharp facts covering as many aspects of MMT as possible. Am currently trawling through the blogs creating my own, but why re-invent the wheel? Having no problem with the logic of the message so far, would like to start at the end and work my way back if possible? Like seeing the jigsaw puzzle whole first – for me! Thanks …

jrbarch

JR Barch

I was wondering if you had seen this simplified, stylised version of MMT https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=1075

Thanks Sennex – I had read that blog: am wishing for a complete frameworks that extends to most aspects of the economy if possible? Somewhere between an index and a broad synopsis – even a bridge can be described in a few well chosen formulae – so am wishing for a list of short, sharp concepts that depict MMT. e.g. These are my first few entries for the concept of Government:

Government Sector –

1) A sovereign government spends first, so that the non-government sector can pay its taxes and net-save;

2) It credits balance sheets with a stroke of the pen, and does not need to steal, beg, borrow, or work to do so;

3) Its economic constraint is that it can only purchase what is available for sale – further constraints are ideological, environmental, or resource based;

4) It spends by crediting balance sheets and taxes by debiting balance sheets – governments do not spend by ‘printing money’;

5) Physical money is a separate system to the actual monetary system which is entirely balance sheet entries;

6) Govt. creates money out of nowhere and destroys it through taxation or bond sales – sending it to nowhere!

7) The idea that a sovereign government needs to ‘finance’ itself through speculation, borrowing or enterprise, is like a “fish in the ocean getting thirsty and begging for water from others” (Kabir) – it is completely nonsensical, systemically painful, mocks human ingenuity and is ultimately, comical! “Every time I hear that it makes me laugh” (Kabir).

Idea is to build up the picture with very brief, sometimes personalised statements, easily digestible – that help me to understand.

Cheers…

jrbarch

Dear jrbarch

I am very short of time at present but will catch up on all comments soon.

best wishes

bill

Nice job summing it up with humor, Bill. Here are a couple of political observations.

First, while some of the shortcomings in current economic orthodoxy may be genuinely due to ignorance of stock-flow consistent macro models, there is also a strong incentive not to find out, and I find it hard to believe that others are not being disingenuous. I may be cynical, but it doesn’t seem possible that some people aren’t well aware of national accounting principles, for example, those directly involved in Treasury and Fed operations. The playing in the US is tilted so that income and wealth rise to the top, and the current economic universe of discourse supports this, especially in relation to its use in politics. The right has been working since FDR to rescind the New Deal and subsequent “big government” social spending programs. So whether in genuine ignorance or not, these fundamental errors are being used to tilt the playing field, and otherpolicy solutions are marginalized.

Secondly, many Americans are brainwashed with the idea that the US “free market” economy defeated Communism, which is equated with socialism, and is largely responsible for American “exceptionalism.” There is also significant bias against the economic policies of European countries, especially Scandinavia. The people in charge know how to push these buttons to get ordinary folks to vote against their own interests.

A corollary to this is the fact that there is a lot of bias in the US that is socially and racially based. “Socialism” and “redistribution” are code words for don’t tax me to keep “them” on the dole.

As a result the cry against “spending” is always against social spending, except from the left, which is marginalized as unpatriotic. Military spending is sacrosanct, and the financial oligarchy has a key to the treasury. holding the country hostage when they get into trouble.

Unfortunately, there are as yet no vocal proponents of MMT solutions with a soap box, let alone a bully pulpit, although Warren Mosler is courageously running for president. It’s a start, but, so far I haven’t seen a blip about it. I’ve been writing recently on a few progressive blogs, but have been pretty much dissed as ill-informed or unrealistic by progressive that have been brainwashed into mouthing neoliberal slogans, blithely unaware that they are stumbling into the trap set for them.

Tom: Which blogs? Maybe some BillyBloggers can help out.

I comment on Ian Welch, Open Left (Paul Rosenberg),and Washington’s Blog. ( I also use “tjfxh” as a monicker.) These are political blogs further to the left than most liberal (establishment) and other progressive (grassroots) blogs. The moderators are interested in the political import of economic issues and they are somewhat conversant in basic economics as it relates to policy. Paul Rosenberg basically agrees with the fundamentals of MMT, but I don’t think that he really gets it in terms of stock-flow consistent macro models. I had a go around with Ian Welch a few weeks ago on MMT, and he said he’d check it out and get back, but he hasn’t yet. Washington is sympathetic, but unfortunately he often seems to get stuck needlessly in orthodox memes that are counter-productive for progressives. While these blogs are not widely read, they are somewhat influential on the left. Washington’s blog is syndicated pretty widely though, e.g., on Seeking Alpha and Zero Hedge, so the comments could be read through these venues if readers are motivated to go to Washington’s blog.

I also occasionally comment on Paul Krugman’s Conscience of a Liberal, Mark Thoma’s Economist’s View and Zero Hedge. There are one or two people who apparently know something about MMT and have been encouraging on Mark Thoma’s blog, but they generally don’t post on MMT. and ZH are widely read and influential. Whether many people read the comments is a question though. I have noticed that Krugman will occasionally do a follow-up blog that could have been influenced to something I brought up, but that’s hard to tell. Plus, he says a lot of stuff that indicates that he’s not yet a “convert.”

This is an important “mission,” in my opinion, given the state of the nation and world, and where things seem to be heading a handbasket. I found out about MMT through a comment of Ramanan only a few months ago (where I can’t recall). When I first read his comment, I thought it sounded a bit far-fetched, but he provided references and I followed up. To say that I was astounded is to put it mildly. With MMT everything that you intuitively surmise is weird in mainstream economics suddenly falls into place. I was delighted to find a wealth of information online, but I may never have stumbled on it. For example, Bill’s Stock-flow consistent macro models sums it up, and Wray’s Understanding Modern Money gives the blow by blow, both in terms that virtually anyone should be able to understand.

Kudos to Scott, JKH, winterspeak and others for schooling or at least trying to school dyed-in-the-wool Nick Rowe. And a big salute to Warren Mosler for intrepidly taking on the teabaggers, most of whom are Austrians and ill-disposed to anything but “sound money.” Keep up the good work. But admittedly, it’s a slog. Nick drove JKH to profanity in a recent thread. Yet, JKH gallantly stuck it out.

Of course, RSS feeds are often the only thing that people read so a great number of folks never even see the comments. That’s a big reason to educate the bloggers themselves, so that the good news may eventually get moved up above the fold. The more people that get involved the better. There is only so much time, and lots of places to try to get a foot in the door where an understanding of MMT could do some good. More fingers on the keyboard are needed.

‘”The tax revenue is accounted for but ‘doesn’t go anywhere’ in a physical sense.”

We should perhaps clarify that something important (call it “money” or whatever) is in fact “going somewhere” when the government collects taxes and makes expenditures. In the U.S., the conservative iconography asserts that taxes are collected from the “productive” (i.e., wealthy) people and expended (“distributed”) to the “unproductive” (i.e., poor) people. Liberals like me assert that taxes are collected from anyone without a good tax lawyer and then expended on the military-industrial complex, drug companies and rich financiers. From either perspective, the real function of taxing/expending has nothing whatever to do with balancing the national accounts books or supporting aggregate demand or underwriting private saving. These are strictly economic concepts, much argued over within the field, and different economists’ interpretations are then exploited by politicians as supposed justifications for their actual use of taxing/spending to accomplish their specific socio-political agendas (whether conservative or liberal).

Within the political process, deficits or surpluses are effects, not causes – they are the “leftovers” from the use of tax/expend to move money from one set of pockets to another. Deficits have predominated for the last 40 years in the U.S. simply because it buys you more favors and gets you more votes to expend than to tax, The cyclical attacks and counter-attacks over gov’t deficits and debts (the group out of power attacks the group in power over their “tax and spend” or “borrow and spend” behavior) are Machiavellian politics and nothing else. The media fools you correctly chastise don’t (or pretend they don’t) understand either the economics or the politics involved and they egg on the politicians to duke it out over deficits and debt because it (sometimes) makes good press. In my opinion, this is the reason MTM doesn’t get a place at the mainstream discussion table when we’re supposed to be analyzing, choosing and acting on real economic problems: You guys are actually serious about the intentional manipulation of taxation/expenditure to promote private saving and full employment while everybody else is playing Gimme the Money and Death Struggele for Power. Good Luck!

Actually, Michael, I don’t think that “productive” and “wealthy” are equated in the popular mindset, which is why the “tax and spend” meme works for well for conservatives. Most people in the US think that a portion of their taxes, however little they may pay, goes toward supporting “those people.” The loudest voices protesting this are being raised by ordinary people who are unwittingly opposing their own interests in thinking that cutting social programs will mean lower taxes for them.

This is going to take some explaining, and that means stepping it down to a level that ordinary people can understand. The problem is that most people’s understanding of economics and accounting is limited to balancing their check books, if they even do that. Therefore, they think of the government as a big household. It’s an erroneous analogy that conservatives have no trouble exploiting to their advantage with slogans like “fiscal responsibility,” sound money,” “pay as you go,” and “tax and spend liberals.” Countering this with a simple, clear, and emotionally grabbing alternative is definitely a challenge. Warren Mosler is actually pretty good at rising to this challenge, and he seems to be motivated to go for it in campaigning for president. It will be interesting to see what he comes up with. He’s already come up with a few simple examples that just about anyone can relate to.

Tom Hickey: “…or at least trying to school dyed-in-the-wool Nick Rowe.”

Nobody can be *just* “dyed-in-the-wool”. I have to be “dyed-in-the-wool *something*”. What’s that something? 😉

Hi Nick,

What I meant was that people who see things (data) from a particular point of view often resist seeing the same data from a different perspective. For example, the Copernican/Newton way of viewing the astronomical data and the Ptolemaic are alternative viewpoints. The motion of the heavens can be seen (modeled) in both ways, but the former is preferred because it is a lot more elegant and has much more explanatory power. Cognitive science has shown that certain pathways open through use, while others potential one may not have been opened yet. This is the problem with an established narrative and its attendant norms and memes. It become s conceptual framework that tends to get equated with reality. The teether to reality is evidence, and debate brings out shortcomings of particular views as ways of structuring reality.

While I admire your willingnes to listen to people like JKH, Scott Fulwiler, and Winterspeak, and often respond, I often get the impression that what you are doing in your head is trying to translate what they are saying in terms of MMT into neoclassical-speak, while what they are asking you to do is shift your stance and see what they are saying in terms of MMT. Given their reactions, they may be thinking this, too. To return to the astronomical analogy, sometimes it seems to me that you are trying to translate elliptical orbits into epicycles.

However, I certainly don’t think that you are as dyed-in-the-wool orthodox as Mark Thoma apparently is, given his refusal even to consider the merits of MMT as put forward by a full professor of economics who is widely published, counsels to governments, and is well respected among his peers. This is comparable to a classical physicist refusing to consider quantum mechanics in 1900, or even entertain a model in which discontinuity of motion plays a fundamental role, since “everyone knows motion is continuous.”

BTW, since Professor Thoma has refused to participate in a debate with Bill on neoclassical monetarism vs MMT, perhaps you would consent. After all, debate is of the essence of the shared process of inquiry that we call science. If we can’t get down to measurable evidence that makes a real difference, i.e., that can be checked, then all this is just more baseless ideology. The crucial importance of this isn’t just winning an argument, or even discovering some abstract truth. What we are talking about makes a policy difference that affects people’s lives.

I’m here not as an economist, but as a concerned citizen interested in policy alternatives, and economic policy is foundational to national and global welfare. What many of us are seeking here is explanatory and predictive power that can be put to use policy-wise to address pressing challenges. Down here in the US, we don’t seem to be doing too good at this right now using Bernanke’s monetarism as a policy tool and putting unemployment on the back burner of fiscal policy.

I do want to commend you on your willingness to engage on your blog, where I am learning a lot from everyone. Thanks for hosting the discussions and contributing to them.

Best regards,

tom

Hi Tom. I get what you are saying about different perspectives. And thanks for your thanks, and commendation.

Getting into a debate with MMTers would be worthwhile, for both sides. And I have done it a bit. But the problem is this: there are just loads of other people I want to get into worthwhile debates with as well, to try to understand what they are saying. And I’ve only got one brain, and only so many hours in the day. There’s just so much intellectually engaging stuff out there, and I don’t have any chance of handling it all. I am already spreading myself far too thinly over too many areas. (As a career-move, my own policy has been unwise; even though I can’t stand the thought of doing what I ought do career-wise, which is to narrow down to one petty little specialty.) There are just so many different competing perspectives out there, all demanding our attention. MMT is just one.

And I really sympathise with Mark Thoma. I am amazed he is able to get his head around as much stuff as he does. God only knows how he finds the time to sleep.

By the way, I’m much more monetarist than Mark.

Thanks for getting back, Nick. I well know about falling into the speciality hole. It’s difficult to be a generalist in this information age and also stay on the cutting edge of one’s own speciality. My field is philosophy, which, properly conceived, studies the whole, so I have to be a generalist that considers the key fundamentals of just about everything relevant to life, while also pushing out the envelope in my specialty, which is the philosophy of spirituality (as distinct from religion).

My interest in economics is in terms of political and social philosophy, which is another reason I am chiefly interested in economics as it relates to policy. My approach to philosophy is historical because I believe that human thought is dialectical. The dialectical moment in political economy at the moment is the conflict between neoliberal monetarism, which emphasizes monetary policy over fiscal policy, and what I would call “soft Keynesianism,” which finds a role for both, but emphasizes fiscal policy in a liquidity trap. Given my understanding of MMT, both fail to address the problem at its root, hence, do not resolve the real issue, which is permanently achieving full employment with price stability, a necessary condition for the general welfare. Therefore, I am interested in hearing from proponents of all sides on this issue, and the best way to get the cards on the table in my view is through open and informed debate which is based on evidence, instead of just pitting ideology against ideology, which only leads to disagreement over presuppositions and norms.

I agree with you about Mark Thoma, by the way, which is why I was flabbergasted at this response to an invitation to debate. The classy what would have been to say, “Sorry, time does not permit.” But his response smacks of avoidance. I found that uncharacteristic.

Tim Hickey: Two good political points in your first post above. Plus carry on posting at Washington’s Blog: I nearly always agree with you.

Jrbarch: You’ll have problems finding a “short, sharp skeleton framework” explanation of MMT. Or at least for every “framework” you find, you’ll find a dozen economists disagreeing with some aspects of it.

E.g. take me. I basically agree with Bill Mitchell, Warren Mosler and Tim Hickey about what needs to be done to get out of the recession. But I don’t agree with them that it is tax and tax alone that gives money its value. Plus I don’t agree with them on how money evolved from gold and silver coins to what we have today. I’ve set out my reasons here: http://chartal.blogspot.com

And finally, how about you change your name to jsbach (Johann Sebastian Bach). It would sound very classy. I call myself jpsartre on one blog (Jean Paul Sartre, the philosopher).