The Australian Bureau of Statistics released the latest - Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure…

Shifts in societal attitudes towards well-being mean that a degrowth strategy does not necessarily have to be political suicide

At the end of World War 2, the Western nations were beset with paranoia about what the USSR might be planning. The West had essentially relied on the Soviet armed forces to defeat the Nazis through their efforts on the Eastern front, after Hitler had launched – Operation Barbarossa – which effectively ended the – Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact – signed in 1939 between Germany and the USSR. Following the War, the ‘spectre of Communism’ drove the Western political leaders to embrace social democracy and introduce policies that created the mass-consuming middle class in most countries, which was seen as a bulwark against the development of a revolutionary working class movement and any further spread of Communism. While the interests of capital hated the welfare state and the rise of trade unions, they saw these developments as a means to protect their hegemony in the new world and the uncertainty that the – Cold War – engendered. Mass consumption was akin to Marx’s claims about religion being the ‘opium of the people’ and it has been a dominant part of life in advanced nations in the Post War period. It is one of the reasons that people think a degrowth strategy can never be embraced by the political class because it would confront a population besotted with material accumulation and consumption. However, research from Japan suggests that a strategy designed to reduce material consumption will not “reduce individual happiness and collective wellbeing” (Source) and a decoupling between growth and human happiness is indeed possible, which means the political class, if they are courageous enough, can introduce policies that promote degrowth.

I am also researching the link between growth and human happiness.

The article I cited in the Introduction – Is happiness possible in a degrowth society? – was published in the Futures journal in December 2022 (Volume 144) and was written by three researchers – Hikaru Komatsu (National Taiwan University), Jeremy Rappleye (Kyoto University), and Yukiko Uchida (Kyoto University).

The Japanese Cabinet Office has conducted an annual survey – 社会意識に関する世論調査 (Public opinion survey on social consciousness) – since 1948, which provides a very rich data source for researchers.

I have been working with this data for some time now, untangling the complexity of the information that spans such a long period of time within which the Japanese nation has evolved from a defeated, occupied country with widespread poverty into one of the rich, advanced nations of the world.

The survey interviews produce around 6,000 ‘valid sample’ each year from 10,000 interviewees, which is means it is a great source of data for researchers like me.

Survey officers conduct these face-to-face interviews of Japanese nationals over 18 years of age in locations throughout Japan.

There are other surveys that supplement this data:

1. 日本人の意識」調査 (Survey of Japanese Attitudes) – which is conducted by NHK’s Broadcasting Cultural Research Institute.

2. 日本人の国民性調査とは (Japanese National Character Survey) – which is conducted by the – 統計数理研究所 (Institute of Statistical Mathematics) – Japan’s national research institute for statistical sciences located in Tokyo.

The results of these surveys allow questions pertaining to the link between material growth (GDP growth) and happiness to be interrogated, which helps determine whether there is any political chance that a degrowth strategy could succeed.

Most progressively-minded commentators, who accept that climate change is now threatening human existence, advocate a ‘green growth’ strategy, which entails reducing the fossil-fuel component of growth to help moderate the damage that extensive use of carbon-based resources are doing.

It is a sort of have it both ways strategy and is motivated by the belief that politically it is simply not possible to significantly reduce the material prosperity of populations in the advanced nations through political interventions.

The ‘green growthers’ consider the mass consumption ethos to be so ingrained that it would be political suicide for a political party to advocate retrenching that aspect of our behaviour.

They believe that happiness comes from material growth and so the only political option is to redirect from ‘brown’ to ‘green’, while essentially maintaining material consumption levels.

I recall in my student days, people telling me that capitalism was a natural fit for humanity because we are all self-interested and greedy when push-comes-to-shove.

I wrote about that idea in this blog post – Humans are intrinsically anti neo-liberal (May 22, 2017).

The ‘green growth’ assumption that growth makes us happy is a replay of that claim.

I have also noted before that humanity is currently plundering nature 1.7 times faster than our planet’s ecosystems can regenerate

Please read my blog post – We are 1.7 times over regenerative capacity and the world’s population control must be reduced (August 21, 2024) – for more discussion on this point.

On average, nations reached – Earth Overshoot day – last year on August 1, 2024, which means that we should have all stopped producing and consuming then.

The situation varies greatly across different countries.

What this means is that the strategy to bring resource demand back into the realms where regeneration is possible cannot include on-going growth, ‘green’ or otherwise.

That observation is the basis for moving our focus to a degrowth strategy, whatever that entails.

The question is whether it runs against our desire for happiness, which ‘green growthers’ assume is correlated (at least) with material aspirations.

Commentators point to surveys taken during recessions that show people are more likely to be depressed when they face job loss.

They use that cyclical response as a justification for their assertion that material growth is necessary for underlying happiness.

Of course, it is a poor example, because in a recession, the lower income cohorts suffer disproportionately, while the upper income group tend to prosper – adding wealth (for example, via forced sale of real estate by workers rendered unemployed).

A careful degrowth strategy would not impose these sorts of disproportionate costs on the poorest cohort.

There is a growing body of research that indicates that there is no necessary link between those aspirations and outcomes and our sense of well-being.

The article I cited above is one of several in that category and takes an interesting long-term view by tracing shifts in social attitudes in Japan over the last several decades which the mainstream commentariate initially referred to as the ‘lost decade’ (when the slowdown after the 1991 property market collapse was 10 years in).

The researchers found that:

When economic standards started declining, the level of subjective wellbeing did, in fact, decline during the first five years. However, the level of subjective wellbeing subsequently stopped declining and even started improving, despite no apparent recovery in economic standards.

To establish this finding, they used survey data I mentioned above.

A question in the survey that gave the researchers vital information: How satisfied are you with your current life? – “Respondents were required to choose one among the following five options: (1) satisfied, (2) somewhat satisfied, (3) can’t say either way, (4) somewhat dissatisfied, and (5) dissatisfied.”

From the answers, a “mean level of subjective wellbeing” was constructed.

The results were supplemented by similar answers in the NHK and the ISM surveys.

The interesting outcome of the research and of the survey evidence (the latter which is motivating my own work at present) was the shift over time in the way Japanese people evaluated their sense of well-being.

The early surveys were found to irrelevant in the modern era because of these shifts, which influenced the survey design as time passed.

The cited research noted that:

Japan previously emphasized individual achievement and status, the dominant form of wellbeing underpinning modernity. Yet, there has been a shift in understanding of happiness and wellbeing: away from individual achievements towards harmonious relationships. This shift in the concept of wellbeing might have occurred in accordance with the decline in economic standards. Individual achievements would require an abundance of resources, opportunities, and thus greater materialistic consumption, a difficult set of conditions to maintain in a society with declining economic standards.

That shift is demonstrated in a number of research papers and is very interesting because it suggests that societies adapt to changing circumstances and shift away from dominant ideologies more than we might think.

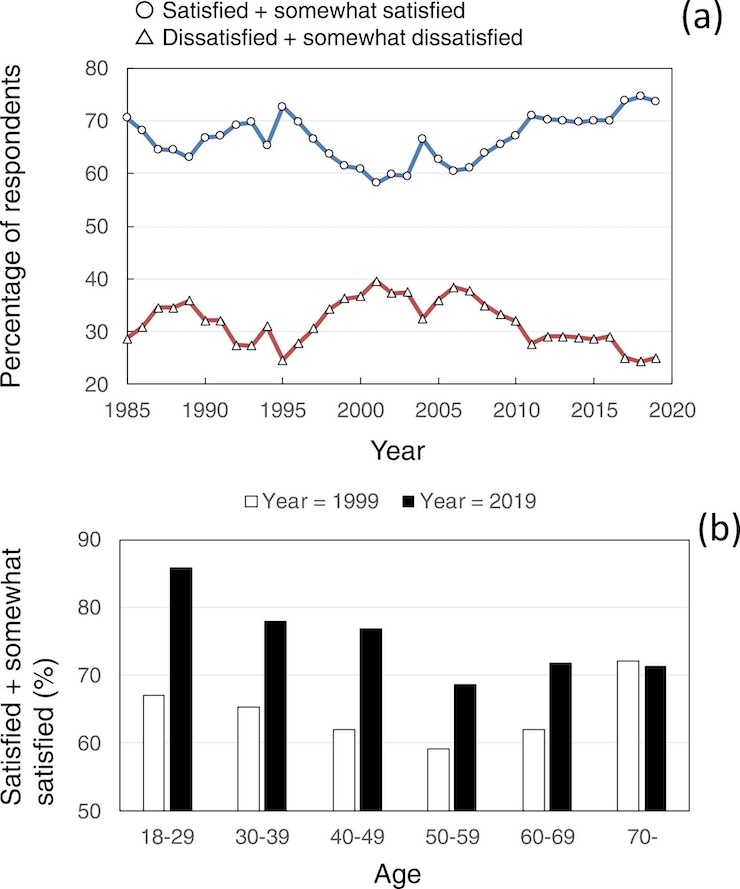

The following graph shows the responses to satisfied and dissatisfied questions from 1995 to 2019 with the lower panel breaking down the responses into age cohorts.

Clearly, in the aftermath of the bubble crash in the early 1990s and the sales tax hike in 1997, people expressed rising dissatisfaction and declining satisfaction.

But after 2000, that pattern reversed.

And as the authors note: “The gradual recovery of wellbeing over the past two decades was greatest among younger age cohorts”.

Further, the responses that supported:

… individual achievement (“do what they want” and “think about themselves”) … decreased, while those who chose the options emphasizing harmonious relationships (i.e., “do something for others” and “help others”) increased over the same two decade span … these tendencies were more pronounced for younger age cohorts …

The conjecture is that the younger cohorts never experienced the rapid growth era in the 1960s and 1970s and so formed different views of well-being.

Other responses in all three surveys reinforced the notion that “harmonious relationships (‘spend time harmoniously with others around me’) were more important to people than “individual achievement”.

The evidence in this study, supported by other psychological studies suggests that:

… reducing an excessive focus on the individual self is one effective way to achieve happiness within material constraints …

Other studies have demonstrated that survey responses that suggest climate denial are highly correlated with respondents who are motivated by a sense of individualism.

Conversely, those who express a deep concern for the climate issue tend to be focused on community and family rather than the individual.

In Japan, there is a growing awareness of the attitudes held by the so-called – Satori generation (さとり世代) – “young Japanese who have seemingly achieved the Buddhist enlightened state free from material desires but who have in reality given up ambition and hope due to macro-economic trends.”

All the ambitions that capital has engendered to render us compliant, mass consumers are absent in the satori generation.

The members eschew: “earning money, career advancement, and conspicuous consumption, or even travel, hobbies and romantic relationships; their alcohol consumption is far lower than Japanese of earlier generations”.

In South Korea the same attitudes are held by the – N-po generation.

When I gave a presentation recently at the Rising Tide Coal Port Blockade in Newcastle I observed many young people who were dedicated to fighting against climate change and ending coal exports and who were seemingly of the ‘sartori generation’.

It gave me great hope.

The researchers say that being sartori is not because of ‘low income’ status but rather, “signifies a shift in mindset”.

What is the relevance of this type of research for articulating a degrowth strategy?

Quite clearly if there is a growing shift away from mass consumption and material aspiration (especially among the young) then the assumptions of the ‘green growthers’ fail.

If a growing number of people are being motivated to live “happy lives with less” material acquisitions and individual achievements then a viable political degrowth strategy is possible.

Conclusion

The next question that needs further work is whether this type of shift in attitude towards well-being is a Japanese (or Asian) phenomenon that is not evident in the advanced western nations.

Some research is emerging to suggest that the shift is generalising.

The clue is for the education system to change attitudes early.

I will write more on that issue later.

Correction – Episode 10 of the Smith Family Manga

Episode 10 will be published on Friday, January 17, 2025 rather than tomorrow.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Conscription and a few wars will be all the elites require to bring the satori, n-po and other like minded types into line.

There was a John Harris article in the G recently suggesting that the UK government was failing, not just by not delivering social democratic policies (ones far short of the necessary degrowth strategy) but by not transmitting a progressive (even if disingenious) message. One can hardly disagree, when Starmer’s vacuous new year resolution is to restore the UK to being “a nation that gets things done” (but only if the bond markets allow it). It was an article that allowed for comments, so I filled a few idle minutes with the following observation: ‘The ‘story’ that Starmer should tell: if we want a decent society, we have to employ more people in social jobs, and those jobs have to be regular and decently paid, and can’t be delivered for profit. That means a bigger rather than a smaller state sector, and it means the private sector investing in technology and innovation rather than in low paid jobs to make profit out of questionable advertising driven consumption and out of state subsidies. It means restricting the choices of the wealthy to consume what they want, be it education, private health care, or environmentally destructive lifestyle choices, which distort the market and government action to the detriment of everyone else and future generations. Will he tell that honest story? I don’t hold my breath.’ The two replies I received, ‘that sounds like a tyranny’ and, to precis, ‘you’d have to abandon democracy and that has always led to Stalin type inhumanity’ no doubt represent a view held not just by progressive G readers (haha) but a much wider number. Is there any hope for the candle flame that Bill (and Japanese youth) keep alive? Well, yes, I think so, as it’s better than complete despair. We shouldn’t forget the reengagement with politics, particularly among young people, that Corbyn brought about, nor indeed the reengagement effect of the EU referendum (though sadly young people were conned on that one). That groundswell is still there, as it is in other western countries, and will only grow, no matter the fierce put-down by the Establishment.

Somewhat strange wording by Bill at the start of his blog: ‘The West had essentially relied on the Soviet armed forces to defeat the Nazis through their efforts on the Eastern front.’ We know that the Nazi Germany Eastern front defeat was key and at the cost of collosal numbers of Soviet Union soldiers and civilians, and that the USSR (was forced to) joined the war on the Allied side before the USA joined. But let’s not forget the USA’s role not only in defeating Nazi Germany, but also in defeating Japan, while the Soviet Union and Mao’s communists stood largely idle. (If the Soviet Union had engaged fully with the western allies in fighting on more than one front, long before the end days, would the USA have dropped the atomic bombs? We’ll never know). And let’s not forget that until June 1941 the Soviet Union not only supported Nazi Germany economically but joined the Nazi’s in invasion of Poland and Finland.

Every country that goes into public debt as a way to supposedly finance public spending, needs economic growth to pay for the interest on that debt.

It’s an ever increasing account, so you need to work harder and harder to pay for it.

If the lent money was badly spent, growth will be even necessary to repay the principal.

MMT can tell you a few things about debt, like it’s mainly corporate wellfare.

I could add: elite’s wellfare too.

So degrowth will be impossible in today’s status quo.

We need a new economic model, but the world is so full of stupid people, telling you lies, that you can only see the morbid symptoms Gramsci talked about.

One of those lies is about the eastern threaths.

One minute, they tell you that nato is there to defend us all from the Russians – who are vicciously seeking to invade europe; the next minute they are telling you that Russia is weak and can be easily defeated (I might add: as long as they deplet their nuclear stockpiles, so that nato begins the bombing of Moskow). How stupid can you get, right?

Can’t anyone see the contradiction?

They are weak, but they want to invade the EU?

Who’s telling you that?

The same ones who went to Afganisthan and lost the war against the taliban.

They can’t even win a war against cavemen, but are very strong at bombing civilians – just look at the middle east or Belgrad a few ago.

The truth is that Russia has a vast territory and a small population, RELATIVE to that territory.

Russia doesn’t have enough people to take over Ukraine.

How do you reckon they could take over europe?

In 1945, those countries that fell under the soviet boot, were destroyed by the nazis and needed help to recover (another thing that never gets mentioned, right?).

So, we’ll have to endure this stupid system until it bursts, or maybe there will be the nuclear war we all fear.

The elites got their bunkers all set.

Maybe israel will not be bombed (after all, both the US and Russia are full of zionists) and maybe there’s a chance that the survivors in the bunkers will end up in greater israel.

As for the other survivors, you should read what the anti-zombie laws say about them.

Degrowth strategies can progress as long as the consumer society is replaced by a true welfare society, if degrowth means stagnation or regression, people will revolt.

For example, I don’t own or want a car, but I think high quality public transportation is extremely important.

Degrowth proponents need to convince people how scientific and technological advancements can occur without the market. Like it or not, people have been led to believe that innovation can only happen through the market and the mass consumption of products.

Strange world we live in, both humorous and sad, when we feel compelled to do exhaustive social surveys and studies in order to determine that most people are made happier by healthy relationships with loved ones than by buying things.

@Paulo Rodrigues Hi Paulo. I think we agree on much, including that the EU is an awful neo-liberal, anti-democratic and interferingly expansionist enterprise. However, I don’t know who you are listening to and believing who say that ‘Russia can be easily defeated’. It clearly can’t, not least with the limit of Ukrainian troops and limited arms supply by the EU/USA, which has been consistently inadequate (compare it to support for Israel) since Russia’s invasion. And ‘Russia wants to invade the EU’ – there’s a reason to be edgy if you live in a Baltic State or Poland i.e. your territory was part of the Russian Empire in the good old days, and very real reason to be edgy if you are Ukrainian of course, but little reason if you live in Portugal. ‘Russia doesn’t have enough people to take over Ukraine.’ True it hasn’t antagonised the people of Belarusia to quite the extent it has Ukrainians, and the population of Belarusia (and the Baltic states) is smaller than Ukraine, but a puppet despot with an army/police is very hard to dislodge.

‘In 1945, those countries that fell under the soviet boot, were destroyed by the nazis and needed help to recover (another thing that never gets mentioned, right?)’. What is your point? If it’s at all relevant, the point might be that the western allies, unlike after WW1, did a hell of a better job of putting western Europe back on its feet, while the Soviet Union concentrated on treating the defeated east as a control zone and stripping it of its industrial infrastructure.

While I wouldn’t trust Trump as far as I could throw him, up till now, the only nuclear threats in recent years have been made by Putin and Kim Jong Un.

Watching Japanese NHK programmes I get the sense that in Japan there is a great appetite for simple, organic, sustainable lifestyles. Nuns on mountain tops living in harmony with the seasons etc. I find the programmes very calming and I aspire to sort of live like that.

Perhaps I am making a virtue out of economic necessity, but I am much happier focusing on things other than consumption.

Paulo Rodrigues: You say: “Every country that goes into public debt as a way to supposedly finance public spending, needs economic growth to pay for the interest on that debt.”

That is plain wrong! Do you not read Bill’s posts? With monetary sovereignty, a currency-issuing central government (CICG) can pay for anything for sale in the currency it issues (in this modern age, with computer keystrokes), including any interest payments on the bonds it issues. Whether there is real stuff for sale in the currency it issues should be the concern of a CICG, which means it should be concerned with the nation’s sustainable productive capacity and, if some of the labour force is unemployed, hiring it and putting it to good use.

Thanks Bill, for revealing how Japan offers some hope. A social laboratory in more ways than one.

I sometimes end up sharing emails in an email group, which includes people interested in degrowth. Here’s what I recently said about degrowth and changing values/way of life. I hope it complements Bill’s post:

There is the ‘normative’ (what ought to be) and the ‘positive’ (what is) aspect to economics, although mainstream economists claim that economics is purely positive and avoids the normative. As we know, you cannot avoid the normative – nothing is ‘value free’, especially economics. The shift to a steady-state economy (SSE) requires a change in values. Without being critical, I see what Spash and others have said in recent times about a change in values as a rehash of many things said in the past. It is nothing new to say that we need to change our value systems to transition to a SSE or whatever is deemed necessary to achieve sustainable prosperity for all.

We can look to many things for inspiration, but I think it is important that we establish what Walter Weisskopf described in 1964 as a “new science of human well-being”, which is not about what we need to do to achieve a high level of well-being and thus enjoy a healthy existential balance of physiological and psychological need satisfaction. What we need to do is of course important, but it comes later, since it’s pointless searching for ways to achieve goals (Intermediate Ends) if we don’t know what the goals are and/or can’t agree on them (appropriately ranked Intermediate Ends). For all its creature comforts, I believe there are very few people in modern society fortunate enough to ‘live the good life’. On the other hand, for all its crudeness and frequent discomforts, I believe most people in hunter-gatherer societies ‘lived the good life’ because their value systems were based on satisfying the full range of human needs, including the need for self-transcendence. There is no reason why we can’t experience some of the creature comforts of the modern world while enjoying the good life (in the broadest sense).

I believe Maslow’s needs hierarchy (NH) is an ideal starting point for a science of human well-being. We begin with lower-order physiological needs and, once satisfied, move on to higher-order psychological needs. Maslow’s NH (1954) culminated with the ‘need for self-actualisation’. However, Maslow believed there was an even higher need – the need for self-transcendence – which involves going beyond personal welfare-increasing goals in search of a higher purpose, which may entail individual sacrifice. Maslow died before publishing his final thoughts on human needs.

If achieving ‘the good life’ implies satisfying the full range of human needs, we would aim to move on to higher-order needs once our lower-order needs have been satisfied. Satisfying lower-order physiological needs involves the production and consumption of only so much real stuff (satisficing). There is no need to produce and consume a lot more real stuff to satisfy our higher-order psychological needs. In fact, the growth obsession results in the production of a lot more stuff than is needed to satisfy lower-order needs and consequently the devotion of insufficient thought, time, and effort to meeting higher-order needs. In the modern world, most people experience an unhealthy existential imbalance. What’s more, the failure of most people to satisfy their higher-order needs, and worse still, the difficulty they have as captives of a socio-economic system programmed to ‘produce and consume more real stuff’, often leads to activities and endeavours that offer little more than a temporary reprieve. Hence, the origins of the modern terms ‘retail therapy’ and ‘consumerism’. At best, both offer short-term relief to a glaring existential imbalance. The relief usually evaporates by the next morning and needs to be repeated – the driving force behind the treadmill of production and consumption. For those who can’t afford to engage in retail therapy, they relieve themselves with a body/mind-altering drug (many people do this even when they can afford a regular shopping spree). Retail therapy and consumerism are addictions no different to an addiction to alcohol, nicotine, or other substance.

We’ve all heard the phrase, “You can’t have everything”. How true. Notwithstanding over-population, it should be possible for everyone to experience the ‘good life’ in relative comfort, but not if most people are devoting their life to the production and consumption of increasing quantities of real stuff. Furthermore, as people get swept up and participate in the treadmill of production and consumption, they contribute to the destruction of the planet. A lose-lose situation. It seems to me that we won’t make the transition to SSE unless we establish an evidence-based science of human well-being, and we are prepared to organise our socio-economic systems around something like Maslow’s NH.

As a goal, I believe degrowth is as meaningless as growth. When should a nation degrow its economy? How much? When should it stop degrowing its economy? Degrowth describes a process – the shrinking of something. Processes are not goals. Herman Daly talked about an optimal scale of the economy – the ideal physical scale of a SSE. He has been heavily criticised in recent times, most notably since his passing, because optimality is non-existent and supposedly a neoclassical concept.

Firstly, Daly used the optimal scale concept as a way of estimating what would be a desirable scale of the economy. He never assumed that it was exact, non-changing, and could be achieved with precision. We know that the marginal benefits of growth decline and the marginal costs of growth increase, even if we can’t measure them precisely. Hence, we know that a point comes when MB MC (when growth is ‘economic’ and desirable) and when MB is clearly < MC (when growth is ‘uneconomic’ and undesirable).

An optimal scale must be an ecologically sustainable scale. If we impose throughput caps, as Daly recommended, we can ensure the Ecological Footprint is no greater than Biocapacity. Hence, we can ensure the physical scale of the economy is no greater than the maximum sustainable scale. Having sorted out the sustainability problem, we should then strive to settle on a physical scale (SSE) somewhere within the fuzzy optimal scale zone and making adjustments, whenever there are unforeseen shocks to the system, which we can do by altering the magnitude of the caps. This is not the same as neoclassical economics. NCE aims to achieve a so-called optimum first, believing that an optimal (efficient outcome) will automatically be ecologically sustainable and distributionally equitable. Daly showed that this is wrong. Technically speaking, an efficient outcome can be achieved regardless of the initial set of circumstances. However, the initial set of circumstances matter. The optimal outcome only makes sense if a sustainable and equitable set of circumstances are in place first. Only then can we make the best of an ideal set of circumstances and achieve sustainable prosperity for all. Making the best of an unsustainable and inequitable set of circumstances is pointless. Would you have preferred to have been experiencing an inefficient allocation of blankets on a lifeboat or an efficient allocation of prawns and champagne on the deck of a sinking Titanic?

Finally, if the transition to a fuzzy optimal scale (SSE) requires the shrinking of a national economy, that is a degrowth process. Most nations will need to engage in a degrowth process prior to stabilising at a SSE. However, there are some poor nations with ecological space which, in order to satisfy the unmet lower-order needs of many citizens, will need to grow their economies prior to stabilising at a SSE. That is a growth process. In both cases, the macroeconomic goal is to eventually operate in the fuzzy optimal scale zone – one that is sustainable, equitable (including full employment), and efficient. Neither growth nor degrowth are goals. They are terms to describe the processes that countries, depending on where they currently are with respect to the optimal scale, need to engage in to achieve sustainable prosperity for all.

One more thing. Mainstream economics fails miserably, not only because it deals inadequately with normative issues, but because it fails with respect to 'what is'. Ecological Economics, MMT, and other heterodox schools of economics highlight how mainstream economics fails to accurately describe the relationship between economy and ecosphere, the monetary system, and the laws governing physical transformation process (production and consumption), just to name a few. Mainstream economics isn’t remotely an accurate description of the economy, its workings, and its place as a dependent subsystem of a larger parent system – the ecosphere. Mind you, individually, the various heterodox schools of thought fail in relation to at least one of these areas (most Ecological Economists don’t understand modern money and virtually all other heterodox schools don’t understand ecological constraints and biophysical realities), and almost all fail in relation to a 'science of human well-being' (most heterodox schools posit GDP growth as the summon bonum of the economic process), as do other disciplines in the social sciences.

I only have second-hand knowledge of the situation in Japan (through family and friends), but comparing what you wrote to this understanding I think you have captured the situation pretty well, apart from one aspect. Japan is no more immune than the rest of the developed world from the change in social relationships, especially amongst the young, so that all relationships, harmonious or otherwise, are conducted far more through social media or other forms of remote communication. I find it difficult to believe that this has not had a profound effect on some aspects of subjective well-being, for better or worse. For example, you mention romantic relationships, and this is just one of the reasons why the birth rate is so low.

@CS

Right, but don’t believe everything you believe on NHK, which is heavily conditioned by the needs and requirements of the government.

Anything with the word ‘degrowth’ in is political suicide.