The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) increased the policy rate by 0.25 points on Tuesday…

Investigation into BBC bias misses the point really

This week, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) released the results of an independent review into its coverage of economic matters – Review of the impartiality of BBC coverage of taxation, public spending, government borrowing and debt – which was completed in November 2022. The problem is that the Investigation conducted by this Review, while interesting and providing some good analysis, misses the overall source of the bias that our public broadcasters have fallen into. The problem is not that they might be favouring political positions of one party or another. Rather, the implicit framing and language they use to discuss economic matters is largely flawed itself. And the journalists who uncritically use these concepts and terms just perpetuate the fiction and mislead their audiences.

The Review was commissioned by the broadcaster in April 2022 and was conducted by Michael Blastland, who is a writer and former BBC current affairs presenter and Andrew Dilnot, who is an economist and was formerly the Director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies and the UK Statistics Authority.

So mainstream economics voices conducting a review into mainstream coverage, which I don’t think is a good start.

In context, the BBC is like a lot of public broadcasters, and the ABC is an exemplar in this regard.

An exemplar of bias in the coverage of economic matters and particularly in terms of the way understandings (or fictions) relating to the capacities of currency-issuing governments are transmitted to their readership, watchers and listeners.

The way in which these public broadcasters have bowed to neoliberal political pressure and constrained the platform they give to so-called experts, while excluding others who actually know things about these matters has become very notable over the last few decades.

There is massive political interference at the top level of these institutions which rely, largely on public funding either directly (in the case of the ABC, or indirectly via the license fee in the case of BBC) for their on-going operations.

I have first-hand experience of this.

Previously, for example, the ABC would get independent academic researchers to provide commentary on economic matters.

Then, around the 2000s, that changed and progressively commercial bank economists would be wheeled in for daily financial updates, replete with their company logos in the background.

The ABC didn’t tell their audience that these ‘experts’ had vested interests in the sorts of things they were commenting about – for example, interest rate speculation.

So the commercial banks were given the platform to push their profit ambitions masquerading as informed reporting.

A senior ABC official told me once that the reason they made this shift was because it was hard getting into contact with academics and the bank economists were always there and willing.

Of course they were.

But the rationale also paled thin given that in the time I am talking about we all have had mobile phones and can be contacted 24/7 basically.

I know that various government officials at various times have pressured various broadcasters who invite me to comment occassionally (less than they used to) to stop having my voice heard.

So it was interesting to read the ‘independent report’ into the BBC.

They enquiry concluded that:

… significant interests and perspectives on tax, public spending, government borrowing and debt could be better served by BBC output and were not protected by a simpler model of political impartiality. We would not call this bias … We did not find evidence of wilful bias …

If it is not bias then what is it?

For a person locked into a particular paradigm in economics, like the mainstream New Keynesian macro approach, it would be difficult for them to detect bias anyway.

The Review was seeing bias in terms of whether it supported Conservative or Labour viewpoints – that is there send of ‘impartiality’ – “to favour particular political positions” – whereas I adopt a much broader concept of bias.

In my reckoning, economics itself, the theoretical and empirical frameworks used etc, is a contested field.

Using terms such as ‘budget’ in reference to government fiscal positions is biased.

How?

While in general usage (from the Oxford Dictionary), the term ‘budget’ refers to some “estimate of income and expenditure for a set period of time”, if you consult the Dictionary you will see the qualify that definition with an example: “keep within the household budget” (Source).

Why is that problematic?

It is because the focus of understanding shifts to our experiences in running our own financial affairs, which provide no knowledge that would allow us to understand the fiscal capacities of the currency-issuing government.

We are financially constrained in our spending choices.

The currency-issuing government is not.

So the bias enters not because commentary favours some political position – Conservative or Labour or whatever – but is intrinsically built into the concepts deployed in the commentary, the tools used to assembling reports, and the language used in those reports.

There is also clear political bias that is possible.

But the bias I am referring to goes much deeper than that.

It is related to the uncritical acceptance of metaphors, language, concepts etc that are in themselves loaded in an ideological sense.

Marxists used to complain about the ‘bias’ in national accounting structures.

Why?

Because the way in which national statisticians assembled the National Income and Product Accounts under international conventions exclude statistical estimates of ‘surplus value’ for example, which is a central concept in Marxian analysis.

That is an example of the hidden or unstated bias in the way we report things which transcends merely supporting one political party more than another.

This sort of implicit bias manifests in who the broadcasters give the platform to, how they express the information, and more.

The term ‘wilful’ is interesting.

I thought about my readings of John Locke when I studied philosophy, in particular his treatment of consent.

Accordingly, we are considered to become part of some society with attendant obligations not usually by directly stating so but by our tacit actions.

He considered the fact that an individual walks along a road provided by the government means they are consenting to the legitimacy of that government and all that goes with that.

‘Wilful’ usually means some deliberate or intentional act.

But if a person is using the national broadscasting platform and the coverage that provides to report on particular specialist topics such as fiscal or economic matters, then they are intentionally holding themselves out as qualified to do so and they present to their audiences in that way.

If, in fact, they are not qualified to do so, or are using the language and constructs of only one economics paradigm, without acknowledging the contested nature of the topic within the academy, then in my view they are wilful, even if only tacitly (through ignorance).

The BBC Report found that:

… too many journalists lack understanding of basic economics or lack confidence reporting it.

I have identified the trend where reporters or presenters, presumably pressured by deadlines and the need to get stuff out every day, take a press release from some institution (think tank, etc) and essentially summarise/paraphrase it as if it is knowledge.

The lack of critical scrutiny of the information and the willingness to merely ‘disseminate’ it further is wilful in my view.

The BBC Report acknowledges this sort of problem:

In the period of this review, it particularly affected debt. Some journalists seem to feel instinctively that debt is simply bad, full stop, and don’t appear to realise this can be contested and contestable.

I would broaden that critique to encompass almost all commentary that we see on our public broadcasters.

Sensationalising headlines and claims such as:

1. The deficit black hole.

2. Maxing out credit cards.

3. eye watering government debt.

and all the loaded language that regularly is broadcast in one way or another by our national broadcasting institutions.

The BBC Report noted the “temptation to hype” to keep the BBC audience from boredom is an example of impartiality.

But it is again also implicitly accepting a particularly paradigmic construction which is also the problem.

The ‘black hole’ terminology and its ilk is explicitly designed by mainstream economists to elicit a sense of stress, of panic, or urgency.

Black holes are dangerous, right!

When journalists then adopt this terminology – and they do it regularly in their written and oral reporting – then they become part of the ideological agenda set by the mainstream economics academy, which then serves particular ideological agendas over others.

The BBC Report also notes that:

Too often, it’s not clear from a report that fiscal policy decisions are also political choices; they’re not inevitable, it’s just that governments like to present them that way. The language of necessity takes subtle forms; if the BBC adopts it, it can sound perilously close to policy endorsement.

How often have you heard (or read) a journalist reporting that the ‘government must now focus on budget repair’?

The language and construction has two problems:

1. The problem identified by the BBC report in the previous quote.

2. The problem with the concept of ‘budget repair’, which is a nonsensical term that implies that any deficit is problematic and ‘repair’ means heading back to surplus, without any additional context being provided (such as the spending and saving decisions of the non-government sector).

Again, the problem I identify is broader than the one the BBC report focuses on.

The BBC Report also highlights the state of ignorance among the BBC audience:

We were disturbed by how many people said they didn’t understand the coverage. In our audience research, most had no comment about impartiality on fiscal policy because they didn’t know what the stories meant …

So the issue is accessibility as well as message.

Having a reporter who doesn’t understand the issue themselves attempt to interview some ‘expert’ is usually a train wreck.

I have watched countless interviews, where the journalist (some very highly regarded ones) repeatedly question a politician, thinking they are building to the ‘gotcha’ moment which will bring them celebrity, when all they are doing is perpetuating the fiction.

Questions like ‘you are going to have increase taxes aren’t you to pay for that?’ repeated ad nausea during an interview with a politician who doesn’t want to talk about taxes at all, just leave the audience with a simple message – government spending uses our taxes and we resent it.

It might appear to be ‘hard hitting’ and all the other terms used to describe these combative style interchanges but from my perspective all that is achieved is that audience has the fictional world of mainstream macroeconomics reinforced.

The BBC Report was trying to find “evidence that BBC coverage of fiscal policy is overall too left or right” when the real bias is the presumption that a currency-issuing government such as the British government is financially constrained and all the fictional logic than then flows from that.

Even if the coverage is neutral to ‘left or right’, the damage is done by what is implicit – it impacts on the type of questions asked in interviews, in the words and metaphors that are used in the reporting and more.

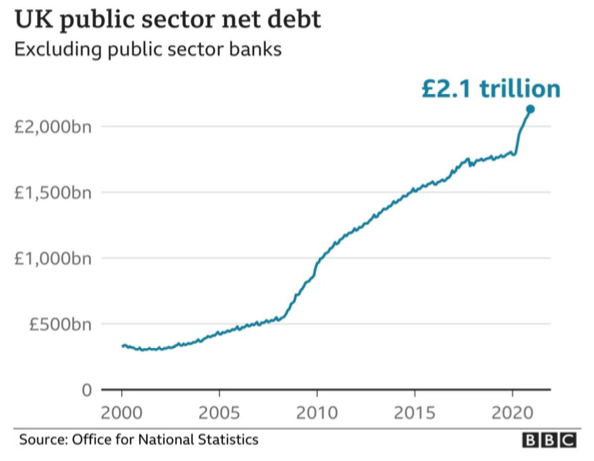

The BBC Report presents an example derived from ONS data on public sector net debt (I republish their graph (from page 7)).

They note that the graph is just factual – so what is the problem? Their reply to that question is:

The problem is there are different ways of framing them.

Yes, but the BBC Report misses the essential point in questioning various aspects of the graph because their framing just reinforces the neoliberal bias:

1. Is the graph “adjusted for inflation” – without relating it to real resource availability.

2. “£s alone don’t tell you how serious a debt is unless you also know about the resources to finance it” – implying that the debt might be serious under some ‘financing’ options.

3. “If national income grows, which it usually does, the same sum of debt will become a smaller percentage of it and generally less worrying” – implying that as some level is it worrying.

4. “the state can usually cope with more debt as it grows richer, just like you” – the household budget analogy, flawed at the most elemental level.

They go on to reinforce the household budget analogy (for example, why is 100 per cent public debt ratio a problem when “many of us could borrow from a bank or building society for a house” 4.5 times that much).

Again, debt “can be ruinous for countries as for people”.

The real problem as I see it is that no reporter ever points out that the national debt is just past fiscal deficits that have not yet been fully taxed away – leaving net financial assets in the non-government sector, which provides the wherewithal for that sector to buy public bonds as a way of diversifying their wealth portfolio.

So the funds to buy the debt come from government.

Have you ever heard anyone on the BBC explain that reality?

That is where the biased framing comes from.

We are trained to think of public debt in the same way we think of our own mortgage or credit card.

And the BBC perpetuate that flawed reasoning.

The BBC Report does have a not on “household analogies” and states:

That states don’t tend to retire or die, or pay off their debts entirely, is one way national debt is not like household or personal debt, not like a credit card for example …

Which misses the point really.

The state is the currency issuer, the household the currency user.

One has a financial constraint, the other can never be so constrained.

Once you understand that then the questions you ask and the answers you accept become vastly different.

It is not that the states “don’t tend to retire or die, or pay off their debts entirely”.

That is true but not the fundamental point of difference.

Conclusion

There is a lot more in the BBC Report that is very interesting but I have written enough today.

My overall reaction is that the Investigators themselves cannot really see through the mainstream smog – they nearly do – but leave the reader uneducated as to the real source of bias in our public reporting.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2023 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

The media is big business.

Forget about journalism. There is no such thing.

If a “journalist” wants to thrive, it has to push someone’s agenda to the fore – if someone is paying for it.

If a “journalist” gives you political party propaganda, without even exposing the contradictions, he’s beeing paid by the donors of such party. It happens every day.

If a “journalist” tries to expose some other political party contradictions, he’s beeing paid by donors of other parties.

If a “journalist” tries to give you comercial marketing, disguised as news, he’s beeing paid by the company he’s “reporting” about.

I know people who are heading the news department of main PUBLIC tv channels for more than 10 years. I believe that’s the road to sleaze.

And these people are imune to scrutiny and investigation: they are untouchables.

What about real JOURNALISM?

Just ask Julian Assange!

The economic debate that has been silenced!

The aim of classical economics was to tax unearned income, not wages and profits. The tax burden was to fall on the landlord class first and foremost, then on monopolists and bankers. The result was to be a circular flow in which taxes would be paid mainly out of rent and other unearned income. The government would spend this revenue on infrastructure, schools and other productive investment to help make the economy more competitive. Socialism was seen as a program to create a more efficient capitalist economy along these lines.

These important concepts that have been abandoned on purpose and how is this deception accomplished?

The first and most brutal way was simply to stop teaching the history of economic thought.

I don’t give up hope that the public have the capacity to understand economics as I think I (thoughtful but not particularly sharp) have managed to a limited degree. After all, we get much more complicated media explanations on other subjects, wildlife, archeology, climate, and indeed are often reminded that scientific understanding is subject to change. There doesn’t seem to be anything too complicated in what Bill can explain in one sentence; ‘…no reporter ever points out that the national debt is just past fiscal deficits that have not yet been fully taxed away – leaving net financial assets in the non-government sector, which provides the wherewithal for that sector to buy public bonds as a way of diversifying their wealth portfolio.’ Perhaps the biggest problem is the ingrained language. Immediately the reporter uses the terms debt and deficit, the listener personalises the government’s position. But there is no deficit, it’s net government spending to allow, in conjunction with bank loans, for economic growth in that year. There needn’t be ‘debt’, because we know that a government doesn’t need to issue Treasury Bonds, but if it does, they are a risk free investment opportunity (an alternative for the corporate world including pension funds, to moving money from a bank current account to a fixed term account). There should be no such thing as a Public Sector Borrowing Requirement. It isn’t borrowing and it isn’t a requirement. I could go on.

Bill. I think a stronger way to have framed this article would have been to compare and contrast hiring 2 mainstream economists to look at economic news with hiring 2 climate change deniers to look at climate news. If the 2nd is terrible why isn’t the 1st at least bad?

In fact there is a 90% probability that the choice 2 MS economists was intentional. If that is true, then that is the point and your audience isn’t the leaders at the BBC, it is the viewers of the BBC coverage.

In fact, they needed 3 guys and 1 of them had to be a non-MS economist, like Steve Keen if not an MMTer. Just like using 2 climate scientists and 1 climate denier. Leaving out one side completely is never a good idea. Except when it is. Like my idea that after the US has suffered over 100K combat deaths to snuff out an idea, that idea should not be allowed any more in the US. So, nobody should call for a return to Black slavery or any slavery.

Bill, I do not understand your aversion to the word budget.

Look at the other meanings of the word:

“B2. the amount of money you have available to spend. Example: an annual budget of $40 million”

“B3. an amount of something such as time or effort that you have allowed for something in your plans. Examples: Find a vacation to suit your time budget; The app sets a budget for your calorie intake”

The government budget fits exactly those meanings. It’s the amount of money that Congress approved and allowed for a given year according to its plan, so it’s the amount of money that government has available to spend. It is also the amount of resources that government is allowed to spend.

Also, “government budget” is something really easy to understand, while “government position” is something that I have no clue what means. Position in relation to what?

@André I think we (especially the accountants amongst us) are all familiar with ‘budget’. The problem with it is that it implies a physical restriction, not just self-imposed, with some penalty for overspending in the period, no matter the good reason e.g. a drugs overspend which has saved lives has to be made up for in restriction of some other health care in the same or a following year. But for a government, there isn’t this same consequence unless it is self-imposed. Of course one should have an initial spending position and approve changes in order that resources are used efficiently, and even try to ensure that the initial spending position isn’t exceeded if it would mean depriving other spending needs of resources, but it’s not the same restriction facing the private sector or non-currency issuing local government. It’s simply doesn’t work to use the same terms while expecting every spokesman and listener to remind that it is different for government.

Patrick, I’m not so sure it implies physical restriction.

For example, when someone is trying to find a house to purchase, and she says “this house is over my budget” it doesn’t mean that she lack the money. Maybe she has the money. What it means is that she did some sort of financial planning and decided that she would allow only a certain monetary amount for buying a house, and the price of house in question is beyond that amount. Maybe she has a lot of money but reserved a big chunk to other stuff (vacations, child care, leasure etc).

That’s why I believe it fits perfectly with MMT. It doesn’t mean the money is physically lacking, just that the government choose not to spend more according to its plan.

The BBC’s economics editor (Faisal Islam) is paid more than £300,000 a year, which puts him in the top 1% of UK taxpayers.

No wonder he doesn’t question the establishment narrative, regardless of the damage caused to British society.

Spot on! Let me tell a little personal anecdote.

Decades ago, while I was struggling to attend uni, I used to work as a proofreader for a big newspaper. The main business/finance reporter at the time (he died yonks ago, btw) had long covered those stories and everybody and their dog knew him. Over the years, he had established a friendship network with people in big companies, business associations, think tanks.

His mates used to pass him in exclusivity documents in paper form. Personal computers, at the time, were only for aficionados and nerds. To write his stories, that bloke would literally cut and paste paragraphs (I repeat: literally) from those documents to assemble his stories.

The joke among proofreaders was that he was the only writer in the world who did not need a typewriter. Scissors and glue was all he needed.

Reply to @André

You missed the point about using the word “budget”. It is not that there aren’t dictionary uses that are consistent with MMT (such as energy and other real resource budgeting) but rather the common mental associations attached to the word.

If you have to spell out which semantic meaning you are employing in the media all the time it becomes only partially better, Ben cause the psychology of the language still dominates your nuance. Nerds and pedants are not helping much here.

It is far better to employ entirely different paradigm changing language, so for government fiscal policy it should be something like “investment schedule” not “budget”. The government policies in any case currently always have a “budget” for employment as some sort of NAIRU as well as some sort of debt limit. These common “budgetary” associations are fraudulent, so we aught not use them. This suggests avoiding the word “budget” entirely and instead saying exactly what you mean, so spelling it out in full. When you do that the word “budget” in relation to fiscal policy disappears.

If the government is targeting some emissions limits, say, that is a physical “budget”, but why not provoke the correct mental framing? Which is “emissions target”. There is no need to be cute and use the word “budget” here, which fires brain neurons for thinking in terms of monetary resources, which would be false. You never budget for a certain number of earthquakes each year. If you do you are going to kill people.

You instead simply have disaster relief planning. There is no budget to that, unless you are neoliberal. But even a neoliberal will fail to “stick to their budget” if a magnitude 8 earthquake hits a city.

There is a spectrum here, but the word “budget” is definitely at the strong constraint end of the spectrum.

“Allowance” is a synonym at the weak constraint end of the spectrum.

For many appropriation bills, “affordance” may also be a useful word.

MMT suffers from the (widespread) bias against the abstract. Fiat money is the critical abstraction in MMT that many people have difficulty educing.

This difficulty in forming an abstract conception of (soft, fiat) money manifests itself in the framework and language, and appears as “bias,” as “uncritical” thinking. But the underlying cause of adoption of the framework and language is the inability to educe the abstraction of fiat money (e.g., the household analogy).

Bijou,

Yes, you have a point.

Maybe in my own mind I associate the word “budget” with a soft limit, but it seems that the majority of people don’t (although I’m not sure). If that’s the case, the word should be avoided.

However, “financial position” or “financial statement” are much more obscure and hard to understand terms. They make it even more difficult to understand what’s going on, which is the kind of environment that ideological manipulators love.

I don’t know, in my view there doesn’t seem to exist a good solution for this riddle.

reading some of the journalistic and opinion responses to the Jim Chalmers pseudo-manifesto in the Monthly was a case in point of what Bill Mitchell is arguing here.

furious consensus in the TABS and “need for balance budgets” framing of the entire discussion and critique responses from everyone. be it senior political journalist Michele Grattan (who went down that path harder than most, save maybe we’ll loved public intellectual Piers Ackerman) or ex-Treasury offical (not meant as a slur) and academic Steve Hamilton (a visiting fellow at the Australian National University’s Tax and Transfer Policy Institute) to idiot-level-hypocrite news corp columnists invoking communism to PR-consultant-cum-opinions-for-a-price Parnell Palme McGuiness mocking the essay for being vacuous (pot-kettle-black, madame?).

not one single one of them them questioned the centuries old neoclassicism and decades old neoliberalism as the appropriate frame to assess his piece in. nobody questioned the hopelessly disproven Phillips Curve methodology or mis-supposed linkages between unemployment and inflation. etc etc.

nobody has ever questioned the (galling) duplicity that’s central to Chalmers’ rhetorical set piece arguments since before the election for “budgetary reform” on the one hand (read “balancing the budget” rather than “balancing the economy”) while cribbing lines from MMT aware economists such as “non-inflationary spending”. except maybe Guy Rundle who is awake to Chalmers the Rhetorician.

i’m yet to read his 6000 word essay, and The Monthly made it annoyingly difficult to create an account to read it under the free one article per month limit (each time i logged in and then clicked on the article it asked me to log in again, and accidentally after three failed attempts i clicked on the Hillsong article by mistake (bad layout/UI in the article listings at fault) and so i got to read that for free instead. gréât. so i’ll be waiting till next month if i bother at all, given the echo chamber of irrelevance it dropped into i’m not sure it’s worth the energy.

@John people can’t understand the high concept abstraction of fiat money that’s been around almost since money began but happily understand the abstractions of crypto and « invest » in crypto (possibly due to FOMO)?

in fact it’s the crypto-libertarian-austrian-school-conspiracists who are doing a great job of explaining the concept of fiat and their particular take on why fiat issued by any sovereign government is inherently such a bad thing. (we can have their god-given sovereignty as an individual with no dependence on anything other than their religion undermined by a system of collectivism that seeks to look after people and planet can we?!)

Hello

I found Bill’s website by accident, and, since I have never been able to see the point of “economists” or their predictions, which seem usually to fail (IMF, OBR, etc.), I read it’s contents at least once a week in the hope of learning something. The problem is that proponents of MMT use similar jargon to their mainstream opponents, which means that I and the other customers of the BBC remain in the dark. Apparently the famous J K Galbraith described economics’ chief quality as giving legitimacy to astrology….

CORRECTION: The BBC’s economics editor was paid between £240,000 and £245,000 in 2021-2022 – still an ungodly amount and still putting him in the top 1% of UK taxpayers. (Other journalists were paid more, some over £400,000, by the public service broadcaster).

@Stanley Beardshall,

If you want to lean about MMT and economics, I suggest that you google Randel Wray & primer.

The primer has many short posts online that explain things simply step by step.

@Steve_American

‘Randall Wray primer new economic perspectives’ :o)

A good source.

@John B.

Among the highly educated and prolific professionals in various fields of arts, humanities, sciences, including university teachers and journalists, I encounter frequently the vocal “no, economy is not for me” or the silent disbelief “are you kidding me?”. Both responses betray a degree of snootiness. Who represent the first think that the knowledge of economics is too tedious or ‘mathematical’, those who represent the second think that it’s too simple or materialistic to bother to think about.

To a certain degree, the educational system can be blamed for this kind of state of affairs. All the textbooks on economy that I had to read in school were wordy and dry, full of disconnected data that was hard to memorise, as if these were written by politicians who are good at putting their audience to sleep.

Textbooks of mathematics use frequently economic transactions and other processes to set up exercises to be solved. In mathematics, a particular case represents a general case. This kind of learning experience can create a cognitive dissonance where the empirical economic reality is perceived as a mathematical tautological reality.

@Paulo Rodrigues

Certainly, journalism exists. Journalism exists in two forms: publicly and privately owned. You’re describing private journalism that has to think all the time about how to earn money. A private company, a private media outlet cannot exist without making profit.

The expenses of public media, distinctly, are covered by government budget.

Salman Rushdie has written about how publishers tend to make editors redundant and hire marketing specialists instead. As a result, the books sell better, the profits rise, but the quality of books is in decline.

Governments can always spend as much money on public media quality as it takes. BBC journalists who keep supporting the orthodox financial theories perpetuate, this way, their own feeling of financial insecurity that has no grounds in a government owned media outlet.

A little pedantic perhaps, but I know Bill likes to be accurate. The BBC is the British Broadcasting Corporation, not Commission. They were kind enough to employ me for 21 years so I’d hate to see this error continued.

This week on air a BBC Economics Correspondent stated the G’ment isn’t like a household, can spend whatever it’s wants, and went on to imply inflation was the main threat. Regardless of interpretation re inflation risk, it’s wonderful to hear the actual facts reported. I think he’d been reading Bill or Bill’s MMT colleagues rather than the BBC review.

@Matt R, Sadly I doubt they’ve been reading any real MMT comment. This fact is quite widely accepted without a sign of any deeper understanding.

This is a tweet from Dan Neidle (Tax Policy Exchange who brought down Nadhim Zahawi) today in a thread where he had previously pronounced MMT as opaque:

“I do agree with them that the way journalists and politicians talk about govt finances as if they were household finances, govt ‘running out of money’, ‘going bust’ etc isn’t very helpful when govts (at least those issuing their own currency) are very different to households.”