I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Signs of recovery prompt cries for surpluses

This week’s Economist Magazine (print edition) is running a story Making fiscal policy credible – Bind games, continues the mounting conservative push for governments to return fiscal conduct back to the days before the crisis. The conservatives (except the really loopy ones) are begrudgingly being forced to recognise that the fiscal stimulus packages have saved the World economy from a total disaster. But after taking a deep breath they get back on track with the “debt is bad” “surplus is good” mantra that got us into this mess in the first place.

The article comes with the sub-heading “Can governments bolster confidence that they will act to prevent a debt spiral?” which tells you immediately, by construction, that the article has nothing to disseminate but misunderstandings and worse about the way the fiat monetary system operates.

We can see this article in the context of the latest news from the OECD. They have just released their latest Composite Leading Indicators, upon which they conclude the following:

OECD composite leading indicators (CLIs) for July 2009 show stronger signs of recovery in most of the OECD economies. Clear signals of recovery are now visible in all major seven economies, in particular in France and Italy, as well as in China, India and Russia. The signs from Brazil, where a trough is emerging, are also more encouraging than in last month’s assessment.

The CLI attempts “to indicate turning points in economic activity approximately six months in advance”. The OECD say that the “OECD CLIs are constructed from economic time series that have similar cyclical fluctuations to those of the business cycle but which precede those of the business cycle. Typically movements in GDP are used as a proxy for the business cycle but, because they are available on a more timely and monthly basis, the OECD CLI system uses instead indices of industrial production (IIP) as proxy reference series. Moreover despite their tendency towards higher volatility historical turning points of IIPs coincide well with those of GDP for most OECD countries.”

You can read more about how the CLI is constructed via this Methodology paper.

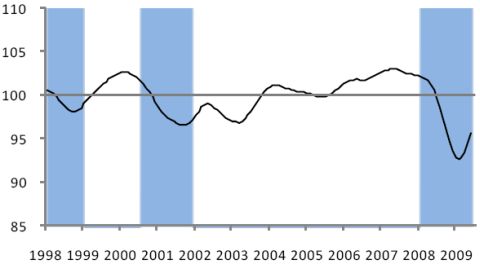

The following graph is taken from the latest OECD Composite Leading Indicators and is for the overall OECD block of countries. The shaded areas are observed growth cycle downswings (measured from peak to trough) in economic activity.

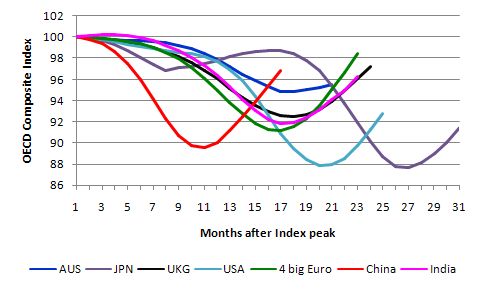

To provide some comparative analysis I assembled the following graph from the CLI. I took the peak index value prior to the current recession for the representative countries shown and made that the base value (= 100) of a new index and then constructed it to July 2009 (the latest observation). The peaks are: Australia (Nov 2007); Japan (Jan 2007); United Kingdom (August 2007); USA (July 2007); The four big European economies (Sep 2007); China (Mar 2008), and India (Dec 2007).

Apart from being nice to look at, you can see the vastly different response to the downturn across the countries shown. China showed signs that it was coming out of the crisis very quickly whereas the trough for the European-Big-4, India, the UK, and Australia more or less coincide about 6 months after China was turning. The US economy then turned according to this in Month 20 of its downturn, 9 months after China turned (relative to the respective starting points). Japan bottomed out in Month 26 of its downturn. So all of the major economies shown are not indicating that GDP will be growing over the next 6 months.

What I concluded from this graph is that it is clear that the automatic stabilisers and the discretionary stimulii interrupted a very serious event. The size and targetting of the stimulus packages (a separate blog is coming on this issue) are highly related to the shape of the recession trajectories shown by the CLI.

The Economist article also thinks that at the anniversary of the Lehman Brothers collapse:

… the world economy is turning the corner … [but] … Policymakers are cautious and in no hurry to withdraw stimulus.

But with the worst behind us, the Economist claims that:

… officials are under increasing pressure to explain how they will reverse course when the time comes. That task is particularly hard when it comes to the public finances. Fragile economies need support from fiscal policy, but it is harder for finance ministries than central bankers to promise credibly to be strict in future when they are so liberal today.

So you get the drift.

First, the severity of the crisis is measured in this construction by the output cycle rather than the labour market cycle. It is the latter which affects real people and takes longer to resolve. But the mainstream economic emphasis is always on the GDP cycle. Once it has turned and output resumes growth it is time to batten down the policy hatches and get the public budgets back in surplus as soon as possible.

Second, the notion of “policy credibility” is often used by the mainstream as the benchmark but rarely is this notion given any credibility itself. Who are th judges? Well, you can guess. It is the financial markets that matter because apparently they can force higher interest rates on the economy and push a double-dip recession onto all of us. More on that later.

The Economist article then makes the astounding claim that:

Scarcely any rich country has stable public finances. America’s public debt is expected to double as a fraction of GDP by 2018. Britain faces many years of budget deficits and a rising debt burden. There is no end in sight for deficits in the rest of Europe either. An obvious danger of large and persistent deficits is a loss of faith in governments’ ability to cap the rise in debt. If bond markets become concerned that governments could default or inflate away their debts, interest rates would jump, choking off recovery.

There are those amorphous bond markets that have to be satisfied!

What do they mean by stable? The inference is that there is a solvency risk attached to the public debt which regular readers will understand is impossible from a technical sense. A specific government may default voluntarily for political reasons but that has nothing to do with their capacity to service and repay any level of public debt.

Further, there is the imagery that persistent deficits are unstable and will undermine the credibility of the governments in question. We have a recent demonstration that this is nonsensical – Japan. You may also like to read the blog – Japan – up against the neo-liberal machine. Both of these blogs provide modern testimony that persistent deficits are in fact necessary as long as the non-government sector are intent on net saving in the currency of issue.

But taking a longer view of history you may want to read this blog – Some myths about modern monetary theory and its developers, which shows how long-term deficits in the US were never unstable. In Australia, the federal deficits persisted right through the high growth period which supported positive private sector saving ratios. Conversely, the period of budget surpluses was accompanied by increasing private sector indebtedness and dis-saving. The latter period set up the conditions for the current crisis around the world.

What the Economist article fails to acknowledge in its mainstream ranting is that if the non-government sector is to save then the government sector has to run fiscal deficits to finance that saving and maintain high levels of output and employment.

Trying to assess the sustainability of a fiscal position without any reference to the saving intentions of the non-government sector nor the capacity utilisation rate and its impact on the labour market shows how narrow and misguided their analysis is. You might like to read the following blogs to gain a better understanding of how to assess fiscal sustainability – Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 1, Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 2 and Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 3.

In the last of that trilogy I concluded that:

But in defining a working conceptualisation of fiscal sustainability I have avoided … very much analysis of debt, intergenerational tax burdens and other debt-hysteria concepts used by the deficit … [terrorists] … They are largely irrelevant concepts and divert our attention from the essential nature of fiscal policy practice which is to pursue public purpose and the first place to start is to achieve and sustain full employment.

The other question that the Economist article author and all the mainstream analysts have to answer is why didn’t the “bond markets” lose faith in Japan as it was issuing massive amounts of Yen-denominated debt each day to match the huge daily injections of net financial assets (Yen-denominated) via the national budget deficit?

Why didn’t bond markets consider that eventually the deficits would have to be inflated away to overcome solvency issues and why didn’t interest rates junpt as a consequence choking recovery? There was a double-dip late in the 1990s in Japan because the deficit-terrorists forced the government (via political pressure) to cut the fiscal stimulus back. Once the government realised their error, the stimulus was expanded and growth returned. Interest rates stayed zero (overnight) and low (investment instruments) and inflation continued to deflate.

The only danger for countries at present is that they will choke off their recovery by withdrawing the fiscal stimulus packages before the labour market has recovered.

The Economist article then offers some suggestions as to how governments should maintain credibility. They say:

One way to bolster trust would be to put fiscal policy on the same footing as monetary policy, by outsourcing budgetary decisions to independent councils with a mandate to preserve fiscal solvency.

So the maintream economists now want to usurp democracy even further – they the “defenders of freedom” – and place both arms of aggregate policy into the hands of unelected and unnaccountable officials.

You might like to read my blog – Fiscal rules going mad – to see what a disaster this would be.

Further, if you think about this suggestion, it is not just the assault on our democracies that is of concern. It also makes no sense at all. What does “a mandate to preserve fiscal solvency” mean?

An understanding of the fiat monetary system will immediately tell you that this requirement would not define any feasible situation where the deficit should be limited. Why? Because the national government, which issues the currency, is always solvent!

So by failing to recognise that the commentary is meaningless. In reality, the conduct of fiscal policy has some strict limitations for sustainability which I outline in detail in the trilogy of articles linked above.

In short, fiscal policy has to aim to achieve public purpose – full employment – and in doing so, maintain nominal spending growth in the economy in line with the growth in the real capacity of the economy to absorb that expenditure. Otherwise, inflation becomes the problem once employment is maximised.

If the mainstream understood that the debate would become more productive. We would not be calling for cut-backs in government spending unless we were convinced that the spending gap left by non-government saving was approaching a state we might call “over-filled” by public net spending. One way to quickly assess that state is to estimate the extent of labour underutilisation.

Labour underutilisation is high in all countries at present which means there is more room for fiscal expansion not less. Once the private sector spending resumes the automatic stabilisers will reduce the fiscal position anyway.

To see that these processes are already in train, a report in yesterday’s Sydney Morning Herald told us about the Budget windfall from economy. The article by Josh Gordon said:

Australia’s recession-defying economy looks set to deliver the budget a massive $17 billion annual cash windfall, slashing the likely size of the deficit and level of public debt by up to a third … Amid growing optimism about the outlook for the economy, private sector economists predict the Federal Treasury will be forced to sharply upgrade its budget forecasts when it releases updated figures this year.

As if anyone who understands what is going would be surprised by this. The Economist commentator, however, understands very little about these things.

They suggest that if governments do not want to go the sensible path of adopting fiscal rules or hiving off fiscal policy “to technocrats” they could adopt a ” fiscal council … [to] … monitor compliance with a budget-balance target” (such as in Chile, Hungary, and Sweden).

For Chile they “pledge to run a budget surplus of 1% of GDP over the business cycle”, which means that they pledge to drive the non-government sector into deficit of 1 per cent of GDP over the business cycle. This is not a sustainable position to adopt and will soon see the public budget balance back into deficit with rising unemployment to support.

The Economist article then suggests that:

.. procedural rules, such as a cap on public-sector pay growth … or a “pay-go” rule that says new spending schemes have to be funded by tax increases or cuts in other programmes … [are sensible options]

They are in fact nonsensical voluntary contraints imposed by the national governments on their ability to achieve full employment and price stability. These rules bear no relation to the net spending levels that would be required to support non-government saving at high pressure levels.

The Economist article then quotes some mainstream economist who says that “America needs is fiscal projections that say something about how and when deficits will be tamed … That sort of detail would help taxpayers and bondholders to form views about future policy. As with monetary policy, fiscal policy works more effectively when people know what to expect …”

This assessment then leads the Economist to conclude that:

Devising sound rules is tricky. There is no good theory on what is the right level of public debt. Then again, there is no robust research that says a 2% inflation rate is better than 4%, even if that is what many central banks aim for. Overly rigid rules may spur tighter policy in a slump, but allowing for the cycle can leave too much wriggle room, as Britain’s fiscal mess shows. But even imperfect rules, if monitored well, are better than none at all.

There is no credible mainstream macroeconomic theory per se nor credible mainstream macro research that can guide us at all.

The only position that is credible and sustainable in the long-term is that public deficits have to provide the “finance” for non-government saving desires. By doing that government net spending underpins full utilisation of the available real resources subject to private sector spending wishes (claims over resource allocation).

If the national government tries to push against the non-government sector’s desire to save by pursuing surpluses (withdrawing aggregate demand), then the downward income adjustments that will follow will bring private saving in line with planned private spending at increased levels of unemployment. Further, the government sector will be forced into deficit anyway.

The mainstream just don’t get this and impose their foolish ideas on the public debate. Fools never learn though.

The best place to start in this quest is for the national government to immediately soak up all unutilised labour resources (persons and desired hours unsatisfied) by introducing a Job Guarantee. The guarantee would unconditionally offer a public sector job to anyone who could not find one at the minimum wage (and satisfactory working conditions etc). This policy ensures that the government does not compete for resources that the private sector is currently demanding.

Once everyone who wanted to work had a job, the national government could then further expand aggregate demand in whatever ways they had sought a political mandate up to the point of full capacity utilisation.

It is clear that the mainstream has no conception of the appropriate role of government in the fiat monetary system.

From a modern monetary perspective, we should just keep arguing the point that the recession ain’t over until the labour market is back to full employment. Given the past 30 years or so, and the persistent rates of high labour underutilisatin that have been witnessed, it is clear that the neo-liberals have kept most economies in a state of sustained aggregate demand shortage.

This demand-deficiency has morphed from high unemployment into both high unemployment and high underemployment. But whether it is persons-employed or working hours that are in excess supply – it still remains that the conduct of fiscal policy over this period has been anything but sustainable.

The pursuit of budget surpluses have committed a significant number of workers to a live of diminished opportunities just to satisfy the mindless ideologically-driven demands of mainstream economists.

Eventually repeated episodes of budget-surplus induced downturns will teach us what the role of government should always be. But the losses through unemployment and underemployment and lost opportunities are a high price to pay to teach us that the mainstream ideas are inapplicable to the fiat monetary system that we work within.

a logically written piece. the indian government has introduced a job guarantee scheme for rural households which has become handy in times of distress especially during the current drought conditions.

On this issue, the psephologist Possum commitatus has concluded from the latest AC Nielsen poll that a huge 76% of Australians surveyed currently approve of the government’s deficit and stimulus spending, with 59% believing that the govt had it about right while another 17% believed that it should have gone further.

Far from gaining any significant public traction with their huge fear campaign, the oppositions “deficit will eat your grandchildren” truck is starting to look like a write-off.

There appears to have been a significant shift in the public’s attitude to government deficit spending.

Bill,

This doesn’t directly relate but couldn’t a Job Guarantee invite people that do not wish to work at all back into the workforce just because they’ll get paid min. wage (getting them off the dole, currently less than half the wage) thus forcing (pricing?) the genuinely unemployed that really do want to work out of the market?

Regards,

Senex

Dear Senex

There are no shortage of things for all to do for a wage. If some people are out of the labour force because they couldn’t get a job then offering them a job and inducing them back into work is good for everyone.

No-one gets crowded out of a job under the Job Guarantee by definition. An unconditional wage offer to all. There is plenty of work just someone needs to offer the wage.

best wishes

bill

Senex, if a person truly does not wish to engage in paid work at all, then invitation would not be enough. They would have to be forced.

If for whatever reason(s) a person does not desire to be in the labour force ie their partner earns enough to support them both at their desired material standard of living etc, then the offer of a minimum wage job would be unllikely to entice them.

Living through the long boom here in this resource town, I could at any stage in the past have gained much more highly paid work but I declined because I value the amount of family time afforded by a regular, stable 38hr working week and also doing a modestly renumerated job that I really enjoy much more than I value the income boost I would have gained by trading these things off to become a well-paid shift worker who can’t even remember what day of the week it is lucky to see their kids more than half the time.

Long story short – if a person doesn’t want to trade things that they value for more money, they won’t actively pursue it.

I still think there is a chance prolonged deficits could eat our grandchildren given the fact that in another 10-20 years when the entire boomer generation is in retirement, the effect of that is quite likely net private dis-saving of quite considerable amounts.

Scepticus,

Government deficits = Private sector surpluses (savings).

Oh and the gold standard ended in 1983.

cheers.

scepticus,

what Alan said.

Plus, decades of permanent deficits did not eat anyone’s granchildren – because we all seem to be here.

I think you both missed my point. People in retirement don’t save – they spend their savings on consumption.

In 20 years we’ll have upwards of 30% of the population, probably still with the most net wealth in this mode.

Therefore I am positing that what has historically always been a large private sector net surplus, will be drastically reduced, if not entirely eliminated. I don’t feel this point can be ignored when disucssing public deficits decades hence (and we must of course take the long view here).

When did we have a large private sector net surplus of late? As far as I’m aware, the last decade has seen more private sector dis-saving than any other time in recent history.

Lefty, in the US and UK I think the private sector was still in surplus until about 2003. Not sure re the position in Oz.

Scepticus

In the US, the domestic private sector has been in net deficit since 1998 until 4th qtr 2008 or 1st qtr 2009, aside from a very brief, one-quarter positive balance somewhere around the recession of 2001-2. The trend from the early 1990s to 1998 was significantly downward, then negative thereafter. Again, the very brief positive balance in 2001 or 2002 (can’t recall exactly which) was quickly pushed aside by the acceleration of the housing bubble.

See the strategic reports at the Levy Institute for the data.

Best,

Scott

I’m not an economist scepticus, just an interested layperson, so perhaps I’m not fully understanding your argument.

I imagine the the overall effect of such a wave of deferred spending coming on line in the future from around 30% of the population will depend upon what the rest of the private sector and the government are doing at the time.

If Bill, Randy, Warren and others are correct, then we can not have had a large private sector net surplus for all these years that the federal government was in surplus. Individuals could still have saved – I did – but the savings of all these retirees would have been overwhelmed by the much larger dis-saving of everybody else.

I guess we will have to wait and see. Small towns in regional and remote Australia aren’t worried about retirees spending their savings, I can tell you. The “grey nomads” are the lifeblood of these places and without them, economic activity in these more out of the way places would shrivel and the urban drift would increase.

Another thing – retirees may not save but they aren’t carrying large debts either. I’m not sure what effect that might (or might not) have, but it’s a fact.

Thus, the money spent by retirees has arisen from savings, not from credit (generally).

scott+lefty – my understanding is that the US national debt is only 28% foreign owned, which implies to me that the US private sector – corporate and household must still be in surplus, unless that private sector has large foreign liabilities. I had a quick look at the levy but couldn’t find the relevant data to back up my suggestion here.

Just to be clear, in general I’m strongly sympathetic to the chartalist viewpoint but I do still have some questions that leave me undecided. Firstly, I’m in the UK, so I’m coming at all this from a UK/US viewpoint, and I’m not clear how much of the UK and US debt can be placed at the door of private sector saving.

Secondly, as you will have gathered from my posts my main concern (I am 33) is the future demographics, both from the point of view of the economy in general and my own retirement plans. It seems to me the issue of demographic aging, and subsequent to that, population decline is not addressed properly by any economic schools of thought. The outlook even from heterodox economists whether of the post-keynsian or austrian bent seems remarkably sanguine on this matter, and more concerned with debt levels (which after all is only a contract) than with things like the number of people available to work, and the number of peolpe requiring social support, which cannot be altered.

My point regarding retiree dis-saving can be simply stated that if the number of workers declines, and if the number of non-working people requiring support goes up, output will decline. That would be a long term secular decline, not a simply recession or even a depression, it represents a transition from recession being the exception to recession being the norm.

Scepticus,

I can see where you are coming from. I think you are leaving out one fact though. While the total workforce may shrink, with technological advancements (productivity growth) you will be able to produce the same amount of goods and services if not more.

I believe the problem you state here is Malthusian in nature. He forgot to think about technological progress. If the Government is able to employ surplus labour to improve our productive base (only one thing they could possibly do) then you will be able to produce the same amount of goods with less resources. The real problem would arise if there were not enough baby boomers to dis-save and buy all of these goods in the future (and the government continued to run surpluses).

Scepticus

The identity we are talking about is the following (probably in a number of Bill’s posts):

Domestic Private Sector Surplus = Govt Sector Deficit + Current Account Surplus

The domestic private sector is the one I was referring to above. You appear to be referring to the following rearrangement:

Domestic Private SEctor Surplus + Current Account Deficit = Govt Sector Deficit

From this, yes, the fact that there is a govt deficit creates a positive number for the left hand side of the equation, but that doesn’t mean the domestic sector is in surplus. As I said before, until the recent crisis and ramped up deficits, the sector had been in almost constant deficit.

Best,

Scott

Bill and Scott,

Are you guys familiar with the literature on “The Fiscal Theory of the Price Level” (Sims, Woodford, Cochrane) and its critics (McCullum & Buiter)? Some of it seems to be groping towards a view of money and fiscal policy in your direction without quite getting there for various reasons (e.g. loanable funds premise). Ricardian Equivalence seems to be at the center of the discussion so I’m also wondering if there exists a definitive paper on RE within the PK literature.

Thanks , Knapp

Hi Knapp

I was working on an FTPL paper several years ago and presented a version at a PK conference in 2006. Yes, there are a number of similarities, but obviously important differences, too. See the Levy WP from last year by Pavlina Tcherneva on the relationship. Pavlina and I have meant to do something together on this for some time, but haven’t found the time yet. Got lots of notes, though!

Best,

Scott

Lefty: is is a chart of the household savings ratio for Australia. As you can see, households were “dis-saving” for a period of time this decade. To be precise, net saving was negative between June 2002 and September 2005.

Scepticus,

You may have to distinguish stocks and flows in your analysis when you look at the data. When you say the rest of the world holds x% of the debt and hence the private sector holds (1-x)% etc, you are talking of a stock. Equations such as (S-I) = … are flow equations.

So as Sean points out households were dissaving for a period of time this decade but you should not conclude the all Australian citizens are in debt or something like that. (I have added the emphasis in period of time in Sean’s comment). The graph shown by Sean implies the wealth level came down for a while and when saving was positive in some quarters, it did not increase high enough to the desired levels.

scott, thanks for clarifying that. Does this mean that nations like the UK with large current account deficits may have less freedom when it comes to deficit spending than ones in happier places regarding the current account, like Oz?

What I often have trouble in discerning in bills posts is when he is referring specifically to the Australian situation and when he’s making more general assertions.

And I’m, positing that technological progress will always result in growth is very much the kind of argument the Austrians make – that everything will turn out well in the end if things are left to themselves, If we rely on such arguments then we can justify whatever we like. The demographic situation, OTOH is written in stone in comparison – pretty much based on who’s alive today and at what age.

Ramanan, your point about flows is well taken. So for a given status quo, if the flow out of the private sector is decreasing (i.e. the private sector surplus is increasing, even if from a negative starting point), then that is supportive of an increased public deficit. That makes sense.

And like I said I wasn’t making any assumptions about Australia, since I am not Australian and know little about the details of oz finances.

Thanks for that Sean. That’s the chart I was digging around for early this morning (I have seen it before). The 2000’s combine dis-saving with a lower general level of household saving than has existed for at least 40 years, perhaps longer.

Hi scepticus.

Here in Australia, we run an almost permanent current account deficit. Not surpising really – we export food, fibre and rocks and import highly value added manufactured goods. We have scarcely had such a surplus for around 50 years. But this has no effect on the ability of government to deficit spend (as far as I am aware).

Hi Scepticus

Regarding the “freedom” to run deficits and current account balance, it’s the other way around if you are a sovereign currency issuer. That is, if your domestic private sector wants to run a 3% net surplus at full employment GDP, for instance, and your current account deficit is 3%, then the govt needs to run a 6% deficit. If the current account deficit is smaller, then a smaller deficit is called for. But sovereign currency issuer can run whatever size deficit is necessary to get to full employment; whether or not the govt is a sovereign currency issuer is the only concern regarding “freedom” to run deficits.

Best,

Scott