Well my holiday is over. Not that I had one! This morning we submitted the…

A cynical fiscal statement from a crooked government

Last night (March 30, 2022), the Federal Treasurer released the annual ‘fiscal statement’ (aka ‘The Budget’), which revealed to everyone how cynical these exercises have become. The statement is normally released in May but the Federal government has to go to the polls then and they are so far behind the Opposition Labor Party in the opinion polling that they decided to bring forward the fiscal statement as a last ditch attempt to bribe the voters with pennies. I hope it doesn’t work. This is one of the most dishonest and incompetent governments we have ever had to deal with – and that is saying something given our history. While everyone is talking about the cash splash – it is offset by a range of cuts and dissipates in a few months anyway – just after the election. And the Government is once again revealing it has not foresight – to deal with the major challenges – climate, aged care, health care, higher education, social housing, etc. I can barely even write about the statement it is so bad.

Cynicism skyrockets

The federal government must go to the polls in May 2022.

It is deeply unpopular and the Prime Minister is now the most untrusted politician around. Even foreign leaders (Macron) call him a liar.

One of his own party came out yesterday and called him a bully, an autocrat and unfit for office (Source).

It will likely lose office at the May election.

So what does it do?

Push out a few dollars on ‘cost of living relief’ packages that end in a few months after the election and claim that they are responsible and looking to the future.

The only future they are looking to is their own grip on power.

There fiscal statement demonstrates the worst in political life where they use their currency capacity for personal ends and ignore the major challenges facing the nation.

Much of the cash splash is targetted at marginal seats that the Government fears they will lose or not gain.

Some of the so-called headline spending initiatives are then offset deep in the detail by cuts with the net figure being much lower.

They think a few hundred bucks giveaways will make us all forget how terrible they have been.

I hope we are not that stupid.

What happened in the statement?

First, things have turned out quite differently to the way the Government was thinking last year.

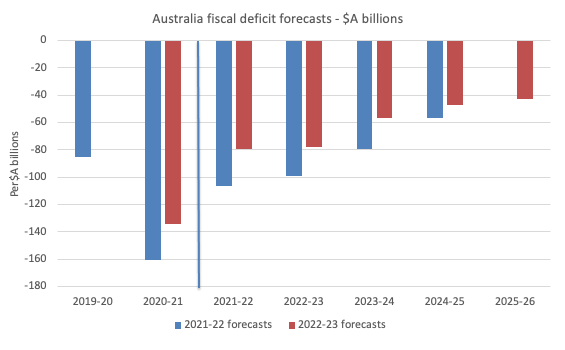

The following graph shows what they thought the deficit would be in the 2021-22 fiscal statement (published May 2021) compared to what they are thinking now.

The bars to the left of the vertical line (betweeen 2020-21 and 2021-22) are actual realised values, whereas the bars to the right are forecasts.

So last year, the Government thought the fiscal deficit in 2020-21 would be -$A161 billion (7.5 per cent of GDP) and it turns out that it was $A134 billion (6.5 per cent of GDP) a 16 per cent forecast error.

You can see out to the end of the forward estimates the deficit is forecast to shrink much more quickly than they expected it would.

Many commentators are now saying that the Federal government overstimulated the economy?

Why?

Because the real variables like GDP growth and employment growth are stronger than forecast and inflation is higher.

Yet, when I appraise the situation, inflation is higher for reasons largely beyond the control of the Australian government’s fiscal position and has little to do with excessive nominal spending.

And, in February 2022, the labour underutilisation rate was recorded at 10.6 per cent, with 4 per cent unemployment and 6.6 per cent underemployment.

With wages growth at record level lows, the economy is still a long way from full employment.

So there cannot be overstimulation with that much labour resource being wasted.

What has happened is that the unemployment rate has fallen well below the level it was forecast to decline (5.5 per cent compared to actual 5.1 for last financial year, and for this year 5 per cent compared to 4 per cent, the latter which will be closer to the actual).

More people are in jobs that they predicted.

Why?

Because the borders have been closed and labour supply flattened out as demand for labour rose with the end of the lockdowns.

I analysed that situation most recently in this blog post – Australian labour market rebounds from Omicron (perhaps) – but it is not as good as the media is claiming (March 17, 2022).

On the revenue side the forecasts were:

2021-22 statement: $A504.9 billion (24.53 per cent of GDP) in 2020-21 dropping to $A496.6 billion (23.3 per cent of GDP) in 2021-22.

2022-23 statement: Actual 2020-21 was $A519.9 billion (25.1 per cent of GDP), foreacast for 2021-22 is $A556.6 billion (24.3 per cent of GDP).

On the spending side:

2021-22 statement: $A659.4 billion (32 per cent of GDP) in 2020-21 dropping to $A589.3 billion (27.6 per cent of GDP) in 2021-22.

2022-23 statement: Actual 2020-21 was $A654.1 billion (31.6 per cent of GDP), foreacast for 2021-22 is $A636.4 billion (27.8 per cent of GDP).

So the government significantly underestimated the revenue it would take out of the economy and has ended up spending more (due to the second and third waves of the virus in the latter part of 2021).

Is any of that a worry?

The only things that matter in this context is whether the fiscal action is translating in real outcomes – like reducing the unemployment and underemployment rate.

And so far, while the borders have been closed that is what has been happening.

The hope I have (pretty weak expectation though) is that the continuing decline in labour underutilisation will be faster than the extra supply of labour that will soon be on us again as companies pressure the government over the borders in their desire to get cheap labour.

While most nearly everyone in the media is talking about the fiscal deficits being large ‘for as long as the eye can see’ and the huge debt overhang (whatever that is) what should be emphasised is the fact that the Government announced a contractionary fiscal stance.

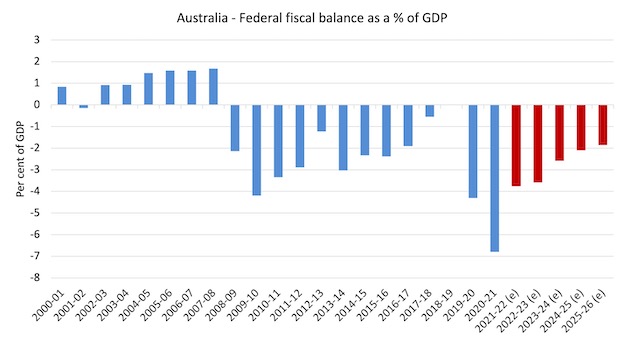

The fiscal statement released last night by the Treasurer has the following forward estimates for the fiscal balance as a percentage of GDP. The graph starts in 2000-01 and goes to 2025-25.

The red bars are the latest projections from the current Government as outlined in Tuesday’s – Budget Paper No. 1.

So, the reality is that the deficits they are shrinking fast through a combination of automatic stabilisation and spending cuts.

For the next three years out to 2025-26, the government is contracting in the hope that the non-government sector will pick up the slack.

In particular, the wage forecasts are overly optimistic, which means that the growth in the related aggregates (including tax revenue) will probably not be as great.

The Net Overseas Migration numbers in the fiscal statement are:

2020-21 (Actual) -89,900

2021-22 (estimate) 41,000

2022-23 180,000

2023-24 213,000

So the period of grace local workers have had since the borders were closed in 2020 has ended and so will the downward pressure on the unemployment rate, as employers will once again be able to pick and choose and suppress wages growth accordingly.

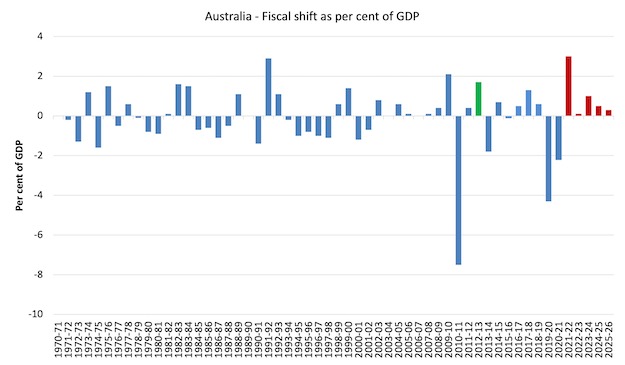

The fiscal shift from one year to another is the change in the fiscal balance as a percentage of GDP changes. It is the result of two factors – the fiscal balance itself (in $As) and the value of nominal GDP (in $As).

The following graph shows the recent history (from 1970-71) of fiscal shifts up to the end of the projection period (2025-26).

I have coloured the current fiscal year (2021-22) blue even though the exact result is not yet known, given the year is nearly done. The remaining red columns are the forward estimates for next year (2021-22) and those beyond.

The green column captures the fiscal shift in 2012-13 (see below).

The biggest fiscal swing in the previous conservative government’s tenure was in the financial year 1999-2000 (a shift of 1.4 per cent).

A sharp slowdown in the economy followed that contraction and the fiscal balance was in deficit two years later (2001-02).

The Australian economy only returned to growth because the Communist Chinese government ran large fiscal deficits themselves as part of their urban and regional development strategy. That spurred demand in our mining sector.

Just prior the GFC, the then Labor government was carrying on about inflation and tightened fiscal policy – and then a year later the biggest shift in the history to stimulus which saved the economy from the GFC.

Then they fell back into the deficit fear storyline and the green bar in 2012-13 was the second-last fiscal statement from that Labor government which was equivalent to 1.8 per cent of GDP.

They prematurely withdrew the fiscal stimulus bowing to the assault from the neo-liberal press and commentariat about the dangers of deficits. It was a moronic and damaging retreat.

A major slowdown followed and dented the recovery from the GFC that had been spawned by the fiscal stimulus in the previous two years.

That Labor government was obsessively trying to achieve a fiscal surplus in 2013-14 and was blind to the reality that the private domestic sector was not going to fill the spending gap left by the retrenchment in net government spending.

The result – which was totally predictable – the economy took a nosedive, tax revenue fell even further and the fiscal balance moved further into deficit with unemployment rising.

The current conservative government was elected in September 2013.

Going into the pandemic, Australia was floundering with GDP growth about half the trend rate, wages flat, household debt at record levels, household consumption expenditure lagging, and business investment negative.

In part, that was the legacy of the huge fiscal shift of the Labor Government in 2012-13, which knocked Australia off its growth path.

But it was also due to the obsessive pursuit of fiscal surpluses by the current conservative government.

During the pandemic the conservatives were forced to expand the deficit through significant discretionary spending programs and you can see that in 2019-20, the fiscal shift to deficit was quite large in relative terms but less than the GFC stimulus that Labor introduced.

In Tuesday’s fiscal statement for 2022-23, the current fiscal position will remain in stimulus, but the forward estimates (2022-23 beyond) show that in the next fiscal year (2022-23), the Government is proposing a record fiscal contraction (equivalent to 3 per cent of GDP).

So for all the big numbers being touted around by commentators, the fiscal statement shows the Government is in large-scale retreat.

And this is while unemployment and underemployment are still high.

I conclude that it is a fail on both sides of the fiscal cycle – the stimulus was too small and the contraction will be too soon and too rapid.

Where is the growth coming from?

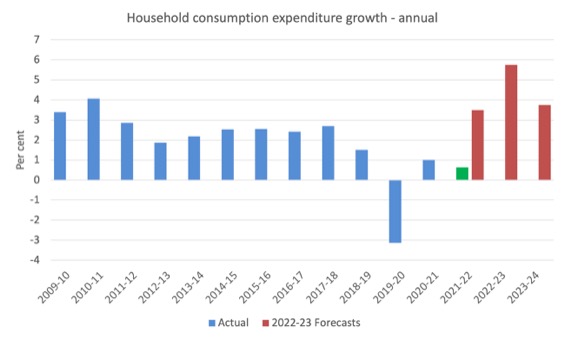

The 2022-23 fiscal statements forecasts that real household consumption expenditure will grow by 3.5 per cent in 2021-22, by 5.75 per cent in 2022-23 and 3.75 in 2023-24.

The following graph shows the annual Household consumption expenditure growth from 2009-10 to 2023-24, with the red bars capturing the Government’s projections.

The green bar for 2021-22, is based on multiplying the sum of the expenditure flows in the September- and December-quarters 2021 by 2 to get an annual result and then calculating the percentage growth for the year.

You can see that the forward estimates are very optimistic based on what is likely to happen in 2021-22.

And the fiscal projections are similarly project a very strong household consumption expenditure growth.

Normally we would expect household expenditure growth of that magnitude to come from a very strong wages growth environment.

But wages growth has been at record low levels and the fiscal statement for 2022-23 is projecting the real wage to drop significantly (by 1.5 per cent) in the current fiscal year and then only modestly grow after that.

The following graph shows real wages growth out to 2023-24.

And the forward estimates of nominal wages growth are far too optimistic, which means that it is unlikely that real wages will grow over the next few years.

Conclusion: The Government is wanting us to return to the unsustainable situation where private debt escalates to maintain household consumption expenditure while wages growth remains flat.

The other observation is that pre-pandemic, households were already increasing their saving ratio and reducing their consumption expenditure growth as a result of the record levels of household debt they were carrying.

So while there might be a temporary spend-up by households as the pandemic wanes (if it does), I doubt that will last for very long and will be sufficient to over-compensate for the fiscal withdrawal that is going on.

We know that the financial balance between spending and income for the private domestic sector (S – I) equals the sum of the government financial balance (G – T) plus the current account balance (CAB).

The sectoral balances equation is:

(1) (S – I) = (G – T) + CAB

which is interpreted as meaning that government sector deficits (G – T > 0) and current account surpluses (CAD > 0) generate national income and net financial assets for the private domestic sector to net save overall (S – I > 0).

Conversely, government surpluses (G – T < 0) and current account deficits (CAD < 0) reduce national income and undermine the capacity of the private domestic sector to accumulate financial assets.

Expression (1) can also be written as:

(2) [(S – I) – CAB] = (G – T)

where the term on the left-hand side [(S – I) – CAB] is the non-government sector financial balance and is of equal and opposite sign to the government financial balance.

This is the familiar MMT statement that a government sector deficit (surplus) is equal dollar-for-dollar to the non-government sector surplus (deficit).

The sectoral balances equation says that total private savings (S) minus private investment (I) has to equal the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)) plus net income transfers.

All these relationships (equations) hold as a matter of accounting.

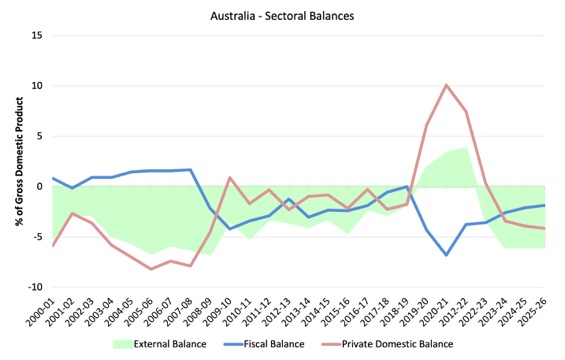

The following graph shows the sectoral balance aggregates in Australia for the fiscal years 2000-01 to 2025-26, with the forward years using the Treasury projections published in ‘Budget Paper No.1’.

The projections begin in 2021-22.

I have assumed that the external position in 2023-24 and later will be the same as the Government’s estimate for 2022-23.

All the aggregates are expressed in terms of the balance as a percent of GDP.

I have modelled the fiscal deficit as a negative number even though it amounts to a positive injection to the economy. You also get to see the mirror image relationship between it and the private balance more clearly this way.

So it becomes clear, that with the current account deficit (green area) projected to return to a deficit of 3.25 per cent of GDP in 2022-23 (as a result of a sharp reversal in the terms of trade), the private domestic balance overall (solid red line) heads towards zero as the projected government balance (blue line) heads towards zero.

In the earlier period, prior to the GFC, the credit binge in the private domestic sector was the only reason the government was able to record fiscal surpluses and still enjoy real GDP growth.

But the household sector, in particular, accumulated record levels of (unsustainable) debt (that household saving ratio went negative in this period even though historically it has been somewhere between 10 and 15 per cent of disposable income).

The fiscal stimulus in 2008-09 saw the fiscal balance go back to where it should be – in deficit. This not only supported growth but also allowed the private domestic sector to start the process of rebalancing its precarious debt position.

That process was interrupted by the renewal of the fiscal surplus obsession since 2012-13.

You can see the red line moves into surplus or close to it. The long-run average private domestic deficit is 1.3 per cent of GDP and was achieved largely when the household saving ratio was between 10 and 16 per cent and private investment in capital formation was strong.

That was a sustainable position because the capital investment was boosting GDP growth and providing returns to keep the debt in check.

The strong fiscal support last year as the fears of the pandemic overwhelmed all the nonsensical deficit scaremongering allowed the private domestic sector to increase its saving (and pay down debt) which was a good thing.

But as the government withdraws its stimulus, the private domestic sector will head back towards deficit and resume accumulating debt.

Overall, the strategy outlined in yesterday’s fiscal statement is once again placing the economy on an unsustainable path relying on household debt accumulation.

The scandals among many:

1. There were no allocations made to deal with climate change.

2. Cuts in two of the next four years to foreign aid.

3. Massive cuts in government support for the arts sector.

4. Despite the problems in aged care during the pandemic and the call by almost everyone to increase the appalling pay rates in that sector, there was no initiatives from the federal government.

5. Despite an out-of-control housing market, there was no commitment to build more social houses for low-income families – disgraceful.

Conclusion

This was one of the more cynical fiscal exercises.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2022 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

I’m glad I was drinking “Heaps Normal” fake beer (delicious, BTW) for budget night. Playing the bullshit bingo drinking game for that speech would have put me in hospital with real booze! I laughed at the key-change near the end, it was like a Eurovision song.

As for the content, meh. Nothing unexpected, and nothing good. Indeed there was some nasty bits in the details, like cutting the arts budget by a full third. How do they expect to maintain a unified national culture? Rhetorical question – they don’t. It’s all about divide and conquer, and the draping of the flag is just a posture adopted when convenient for the news cycle.

What will change under Labor? Well, since they have parachuted Andrew Charlton into Parramatta, I’m guessing the outsourcing of the public service will switch from PwC to Accenture. So not much, unless we are lucky enough to get a minority government.

Still, I guess wrong-but-nicer is better than wrong, corrupt, incompetent, venal and contemptible.

The First Dog on the Moon cartoon https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/mar/30/how-good-is-being-prime-minster-its-one-of-the-main-themes-of-the-budget-along-with-making-climate-change-worse seems to sum it up pretty well: ‘an ideological cluster bomb of a budget. Lazy, shallow and cynical yet also stuffed with cunning and malice’. As a UK resident, I used to draw solace from the thought that Americans and EU citizens had had their countries’ fortunate wealth squandered and stolen to possibly a greater extent. Australia needs to be included in that thinking. So sad.

@bradley Scott, the Least worse option is the ALP as there is currently no alternative. There is the representUS movement (representus.com.au) which planned to field Senate candidates. It is informed by MMT.

It may be a force in the future to either influence Labor or replace it. It will be difficult and a hell of a fight to have neoliberal theology put into the bin.

@Barri TNL are putting up Steve Keen for senate – will be interesting to see. Still I’d love for Bill to be in charge of treasury, or at least advising the government, can you imagine?

@Barri, I’m a house candidate for The Greens. Those of us in the policy workgroups are very aware of MMT – and also of the political/cultural reality we have to work with. So we have the right policy programme (including a job guarantee), of course all fully costed and paid for in accordance with the current paradigm. Or at least Keynes’ version of it.

As a ‘serious’ party that’s as far as we can go, until the mainstream media are capable of hosting a serious debate about economics (or political economy), instead of just a theological debate about debt & deficit between neoLiberal and neoLabor.

Having said all that, it is imperative that we change the government – as the current one is totally ratshit.

A return to a growth strategy based on unsustainable private debt accumulation while the RBA, gripped by inflation-mania, moves to increase borrowing costs….what could go wrong?

@bradley. I saw the 2014 presentation by dr Steven Hail to the Greens but I gained the impression that it was received with disbelief. If my impression was wrong I am pleased about it.

MMT faces much difficulty with credibility with those who are so far down the neoliberal rabbit hole that they are unable to accept what is very counter intuitive.

A few friends and family get the key concepts but others react as if you’ve delusional. The msm by and large wheels out neoliberal economists who always prattle on about “budget repair” etc. but the ABC did recently feature a fair article on MMT.

I will keep trying out ways of explaining MMT to people.