I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Retail sales – a story within a story

Today the retail sales data came out in Australia and showed a 1.0 per cent fall in the month of July and the beginnings of a declining trend (2 negative months in a row). Many economists are seeing this as a sign that the impacts of the fiscal stimulus packages have come to a screaming halt and all we have left for our troubles is a public debt burden that will kill our kids and pets. While the fall-off in retail activity is a problem I don’t think we are about to follow the US path into temporary oblivion. Further, debates about retail sales allow me to extend my Austrian theme. Attack dogs on the ready!

The ABS data shows that retail sales decreased in July 2009 for the second month in a row. In seasonally adjusted terms Australian turnover decreased by about 1 per cent in the month of July.

I was asked during a radio interview this morning what did this mean. The journalist put it to me that wasn’t the fall confirming the view that the fiscal stimulus is a flop – once-off effect and it is now gone.

My answer was that I don’t think you can necessarily conclude anything like that from the data although I didn’t want to argue that the declining retail sales was a good thing.

First, the latest consumer sentiment data also came out today and said we were more confident than we have been for almost 2 years. So how do you square that up with the futility of fiscal policy story?

One of the things that fiscal policy does is to initially inject spending which then has the longer-term effect of increasing confidence. This is particularly when the early part of the stimulus packages were concentrated on consumer hand-outs which were designed to boost retail spending.

The evidence now emerging of increasing confidence should see retail sales rise in the coming months.

Second, the early months of this year saw firms cutting back on investment and households fearing for their jobs. The stimulus packages were designed to ensure that the spending gap that arose from that pessimism didn’t blow out. I think the policy worked and we saw retail sales continue to grow as the rest of the world fell apart.

The interegnum that we are seeing in retail sales performance is a reflection of the fact that the direct household impact of the fiscal packages has gone and there is still a lot of uncertainty in the labour market as last month’s employment figures showed jobs being lost in net terms now.

I think it also shows that we are not back to anywhere near boom times and tomorrow’s labour force data will tell us how poorly the labour market is reacting now that firms have stopped adjusting hours as much as they are adjusting persons employed. I expect the unemployment rate to rise a bit in tomorrow’s data.

Third, the remaining components of the stimulus packages are focused more on infrastructure spending which will favour the retail sector less than the early components.

One upshot of the declining retail sales is that the central bank will keep its twitchy fingers off the interest rate button for a bit longer.

Tale of two economies with some others added

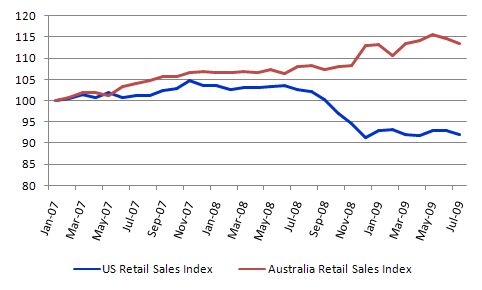

The following graph is for seasonally adjusted monthly retail sales data for the US (data available HERE) Australia (monthly data available HERE). The series are indexed at 100 with the base month being January 2007.

It tells its own story.

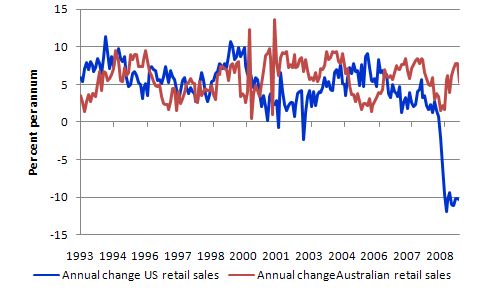

This graph merely shows the annual growth in retail sales for the US and Australia from February 1993. I included it to give you an idea of how severe the current episode is in the US. The scale of the fall off in American retail sales is exceptional in terms of its own history.

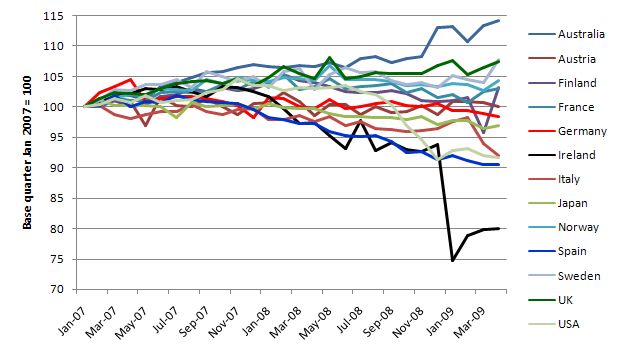

To give you a feel for what is happening elsewhere I used OECD Main Economic Indicators data to construct the following graph which show retail sales indexed to 100 at January 2007 to April 2009.

To help you trace the lines if you take the end points (April 2009) in order from top to bottom is Australia, United Kingdom, France and Finland – all of which have shown overall growth since January 2007; then the countries that have now fallen below the 100 base value in order are Austria, Germany, Japan, Italy, USA, Spain, and Ireland (the latter showing an unbelievable collapse in retail sales since July 2008). A friend just came back from Ireland and says things are very dire over there in the streets.

I may do some separate analysis of the pattern of the fiscal reactions in various countries to see whether they tell us a story about why there are the two groups of countries – those that have seen their domestic retail markets collapse and the others such as Australia. It is clear in Australia that the fiscal stimulus put purchasing power directly into the hands of consumers who went out and spent it.

A theory about Australia

It is fairly obvious that the early and significant fiscal intervention by the Australian government has prevented retal sales from collapsing as they did in the 1991 recession. So it is worth analysing which sub-sectors have shown positive growth and vice-versa.

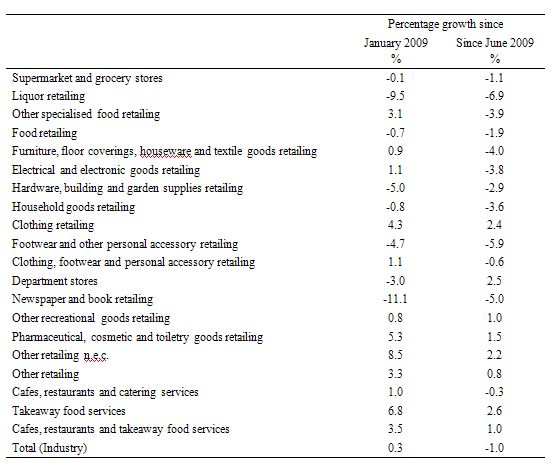

The following table shows the retail growth performance for Australia by sub-sector. I computed the percentage growth since January 2009 (basically the first month after the first stimulus payments started flowing into the data) and also the monthly percentage change since June 2009.

If you examine this breakdown you might come up with the following hypotheses:

H1: Australian are drinking less alcohol and sobering up after decades of alcohol abuse.

H2: Australians have decided that they are obese and have decided to eat less.

H3: Australians have given up on their Bunning’s binge realising that the stuff there is mostly junk.

H4: Australians have stopped buying shoes because they have have too many anyway. I have witnessed this personally!

H5: Australians have given up reading News Limited newspapers because they got sick of the economic commentary! (no link required).

Further we can conjecture the alternatives:

AH1: Australians are going to specialised food outlets to get organic vegetarian-based food as part of a lifestyle change.

AH2: Australians are buying more vitamins and deodorants because they are exercising more (alternative to H1 and H2 and H3).

AH3: Australians are buying more recreational goods beause they are exercising more (alternative to H1 and H2 and H3).

Conclusion: fiscal policy is good!

Please don’t take the theory too seriously. It is just that I am about to launch into a discussion about the Austrian School and needed some levity to prepare myself!

The Austrian take on retail sales

The Austrian School out there would be happy with today’s retail sales performance. They would further be delighted with Ireland’s plunge into nowhere. And the US retail sales collapse would make them delirious.

Modern Austrian School of Economics salesman Peter Schiff wrote on August 14, 2009 that we all had the choice between “less government or lower wages”. That’s odd because historically when government employment growth is strong wages tend to rise (in nominal and real terms).

Anyway, this is what Schiff says:

The nationwide revelry surrounding our apparent economic recovery was disrupted this week by the release of lower-than-expected retail sales data. However, rather than sending a chill up the spines of those hoping for a quick end to the downturn, the numbers should be welcomed. Though this may come as a surprise to most observers, lower retail sales are precisely what our economy needs.

To return our economy to health, we must first allow market forces to wring out the excesses of the bubble years. Even government economists acknowledge that this decade’s spending boom resulted from a combination of asset bubbles and the dangerous overextension of consumer credit. Yet the same economists balk at the logical need for spending to drop now that the stimuli are no longer in effect. They argue for the resumption of spending by any means, regardless of its ultimate cost. This is a recipe for momentary gain and lasting pain.

America’s economic vitality will never be restored until we rebuild our savings and pay down our debts … Unfortunately, Americans cannot accomplish these goals unless they stop shopping, live within their means, and replenish their savings. Though this may be problematic for retailers, it is beneficial to the overall economy.

So apart from agreeing that the private sector cannot go into increasing indebtedness and has to as a sector net save for sustained growth and full employment to be achieved, the rest of this rhetoric is inapplicable to a fiat monetary system.

At present the crisis is one of deflation and failing demand. If the government allowed the market to resolve the problem a depressed state would result very quickly with massive costs imposed on significant sections of the community.

Falling retail sales is an indicator that production and employment and incomes is falling. For many there is a direct relationship between losing their job and entering poverty.

The asymmetry in the labour market response to falling output is marked and the costs of allowing high levels of underutilisation to persist are gigantic.

But of-course the Austrians consider that markets adjust quickly. They don’t. Even Milton Friedman was forced to acknowledge that. He was once ornered on this question and asked to translate the theoretical rhetoric about deflation into practical estimates of adjustment times. He was asked how long would it take for the natural rate of unemployment to be re-established after a period of inflation. He like the Austrians believed that all cyclical adjustment could be made by allowing the “market forces” to work.

He said maybe 15 years or so before the inflationary expectations would be expunged and the economy return to the natural rate. That is, he was arguing for a system that allowed high unemployment to persist for nearly a generation while the market forces worked their way out.

I will come back to the saving arguments in a moment because he adds more to his argument about them.

But Schiff says that the US Government is frustrating this process and

… rather than accepting the market’s medicine, our government is overriding its own citizens’ responsible behavior.

The same behaviour that saw households overburdened in debt. It was the creation of largely unregulated financial markets under the aegis of the neo-liberal onslaught against government intervention that created the conditions that gave the households the incentive to borrow.

The combination of fiscal drag (from the budget surpluses) and a voracious financial engineering sector created the mess. Why should the same lack of regulation get us out of it.

Schiff then says the government has:

… put borrowed money into consumers’ pockets, and then conjured various incentives for them to go out and spend it. This process requires more government bureaucracy, more debt, and more regulation at a time when we can’t afford any of it.

Governments are borrowing at present – the money they injected into the consumers’ pockets in the first place. The conversion of bank reserves into government bonds to drain the excess reserves in the system is not financing the government spending though. It is a voluntary act motivated by governments who have listened to characters like Schiff for too long.

Apart from “dismantling a significant portion of our federal and state governments”, Schiff also claims we have to:

… to restore competitiveness through diminished government spending, deregulation, lower taxes, and higher savings. Higher savings will facilitate capital formation, and lower taxes and fewer regulations will allow that capital to improve the competitiveness of American labor. Improved productivity and capital investment will translate into higher real wages and pave the way to higher future living standards.

So what model of saving lies under all of this?

Saving as a function of the real interest rate

Whether they admit to it or not (and modern Austrians try to downplay the association), the Austrian School utilises the Loanable Funds Doctrine, which was the dominant theory of interest rate determination prior to the Great Depression.

I wrote recently about the neutral rate of interest, which is a notion modern bankers have taken from Knut Wicksell.

The Austrian School also starts with the notion that there is an unobservable interest rate (the “natural” rate) that perfectly matches the time preference of lenders and borrowers in real terms. The currency unit is irrelevant because all the reasoning comes out of a real “corn” model. The introduction of money only places a “veil” over these real magnitudes.

So saving and investment are about desires claims on real resources and the interest rate in equilibrium mediate those claims. As long as the loans market is free to determine this interest rate then saving and investment will always equate at full employment.

So the Austrian School considered the the rate of interest to be determined by the demand and supply of loanable funds present in the capital market.

The way this was conceived as working is as follows. There is a market for loans. The real interest rate adjusts to equate the flows of savings and investment. It is thus a real variable in the economic system (a not insignificant flaw in their model).

To simplify the model we abstract from government and the foreign sector so that investment represents the net demand for credit (or supply of new bonds) in the current period and savings is its net supply (or demand for new bonds).

The model did not explicitly consider the impact of real income on saving. The loanable funds model considers savings as an increasing function of the real interest rate because in the inter-temporal consumption model that underpins this approach, savings is considered to be foregone consumption.

The real rate of interest is the price of present consumption relative to future consumption.

When the real interest rate rises, future consumption becomes cheaper and the familiar substitution effects (outweighing income effects) sees consumers reallocate their spending to future consumption (hence savings rises). Similarly, investment is depicted as a decreasing function of the real interest rate:

The equilibrium interest rate equates savings with investment and is the natural rate in Austrian thinking. This means that it is the rate equating savings to investment at full employment output.

Its existence provides the classical response to the point above that no explicit demand for output has been specified. Demand in our model is the sum of consumption and investment. The natural rate of interest ensures that that the aggregate demand is always equal to the real output supplied.

This is the mechanism that negates (in the classical model) any problems of demand deficiency.

What happens if savings (withdrawals from the income flow) was not equal investment (expenditure injections)?

The Austrians argue that the real interest rate would then adjust. Both consumption and investment would thereby change and shift the aggregate expenditure curve into the correct position. In the classical model, flexible interest rates ensure sufficient demand for the supply-side determined real output level.

Saving as a function of income

The loanable funds doctrine presumes that there is some finite quantity of saving that is available for loans and the demand for loans is then rationed by the interest rate. So investment was limited by available saving.

But in the economy we live in, investment is not limited in this way. Banks create loans which fund investment. In turn, the rise in aggregate demand increases income which then is consumed or saved by households in desired proportions.

Spending brings forth its own saving is a fundamental principle of modern monetary theory derived from its traditions in functional finance. Keynesians also understand this.

Looking at each period, we observe actual saving equal to investment as an accounting statement. But that equality is brought about by income adjustments rather than interest rate adjustments.

To see the problem further imagine that desired saving was not equal to desired investment at the start of some period. The desired investment plans led entrepreneurs to build capital and productive capacity reflecting their long-term expectations of a return. This is what Keynes called “animal spirits”.

The production process then generates a volume of output and if saving is higher than the entrepreneurs expected (that is, consumption is lower) there is unsold inventory at the end of the cycle. Firms react by cutting back production and income generated falls. The falling income causes saving to fall and the process stops until the inventory cycle is finished and firms are selling the proportions of consumption and investment goods they desire.

Of-course, the state of rest that is achieved may result in very high unemployment and is thus undesirable. This is what the unfettered market forces would generate in the absence of governments using their fiscal capacity to fill the spending gap left by the saving desires.

But the point is that saving and investment are brought together via income changes not interest rate adjustments.

So to understand this further we have to start from the idea that employment is determined by effective monetary demand for output. Since there was no reason why the total demand for output would necessarily correspond to full employment, involuntary unemployment was likely.

Keynes revived (although unknowingly) Marx’s earlier works on effective demand. What determined effective demand? In the absence of government and external trade, there were two major elements: the consumption demand of households, and the investment demands of business.

Keynes (in his General Theory) provided a cogent demolition of the classical loanable funds theory. He did this by demolishing their vision of the capital market. To repeat, the Austrians believe that the supply of and demand for capital jointly determined a quantity, namely the total volume of savings and investment, and a price, namely the real rate of interest.

Investment was demanded by firms, with more being demanded at low interest rates than at high. Savings was supplied by individuals, with more being supplied at high interest than at low. Thus a market for capital determined how much of current output would be consumed, and how much saved and invested.

This market, allegedly, operated wholly apart from the determination of output. Investment and savings did not affect employment and output, but only the division of output between current consumption and capital formation.

Keynes attacked the supply of loans story. He argued that savings had nothing to do with the interest rate. They were, instead, merely the residual after households had consumed from their income. Investment, did depend on the interest rate. But a model of investment demand alone could not determine both the volume of investment and the rate of interest. In mathematics, you will recall you need as many equations as there are unknowns to get a solution.

Keynes now needed an independent theory of the interest rate. Keynes analysed a new market, up to that point largely ignored in economics: the market for debt instruments and, in particular, for money. He argued that interest was not a reward for saving, but the reward for giving up the liquidity, the easy access to immediate purchasing power, that could be had by holding money.

As anyone who has bought a bond knows, the longer the term (the greater the liquidity foregone), the higher the rate of interest. Keynes argued that the interest rate thus reconciled the supply of liquidity (quantity of money) with the demand for it. And in Keynes’ new sequence, the interest rate determined in the money market in turn determined the volume of investment.

To complete his theory, Keynes tied these elements together. The market for money determined interest. Interest (together with the state of business confidence) determined investment. Investment, alongside consumption, determined effective demand for output. Demand for output determined output and employment. Consumption out of incomes determined savings. Employment determined the real wage.

Conclusion

Being happy that retail sales are falling is an insane position to take unless you plan to create jobs in different areas of the economy and go on a massive education campaign to condition consumers away from spending.

While I am not advocating a consumer-binge driven society, the reality is that aggregate demand drives employment and saving. If you want to the private sector to save then the government has to be in deficit.

The Austrian School doesn’t comprehend the most basic national accounting. In terms of yesterday’s blog they would not have enough rows in their matrix to achieve stock-flow consistency.

Next stop on this blog tour of the pits will be the Austrian concept of sound money.

Bill,

Keynes is famous for destroying Say’s Law, in the sense that supply does not necessarily assure sufficient aggregate demand.

But in doing this, he also understood well, as you say, that “spending brings forth its own saving”.

It’s always seemed ironic to me that Keynes simultaneously destroyed misunderstandings of two separate ideas, both of which essentially involve the same DIRECTION in causality – the incorrect interpretation that supply creates demand (Say’s Law fallacy), and the failure to understand the correct interpretation that output determines income or that income determines saving or that loans determine deposits (Loanable Funds fallacy).

Does that make sense to you in the way I’ve stated it?

P.S. I can understand the importance of stock-flow consistency, but I’m not quite getting the precise nature of the error you’ve identified in that regard in your last two posts. E.g. I think of the loanable funds fallacy as a flow inconsistency, as much as a stock-flow inconsistency. But maybe I’m splitting hairs here.