I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Why we need more fiscal stimulus

It is clear that next year’s federal election will be based on the deficit-debt-waste agenda, if the mounting calls for the federal government to cut back net spending now to avoid us drowning in a mountain of debt are any guide. However, the political rhetoric is at odds with the major forecasts (such as the OECD and IMF) which confirm that the stimulus packages must not be wound back. The fact that the IMF and OECD are saying that is some endorsement given their neo-liberal credentials. Today, I thought I would do some digging to construct some of my own scenarios. This is what I came up.

I note that despite the political grandstanding over the weekend from the two senior Opposition politicians (leader and treasury spokesperson), one commentator today said that “Turnbull’s “debt and deficit” strategy is in fact a political dead end … [he] … already knows this. It’s just he has nothing else left to fly with”. And that was from a conservative News Limited journalist.

More worrying is that The Greens appear to be buying into the nonsense. In an earlier blog – Neo-liberals invade The Greens – I argued that the official policy of the Australian Greens was infused with neo-liberal thinking. The blog stimulated some debate (see A response to (green) critics – Part 1 and A response to (green) critics – finale (for now)! and I gave two presentations to the Greens (see details).

Anyway, today it is being reported by The Australian newspaper that The Greens want the federal treasury boss “brought before the Senate economics committee to justify the Rudd government’s stimulus spending” and that the Greens leader Bob Brown called “for a raincheck on the $42billion package”.

Greens leader, Bob Brown is quoted as saying:

The economic situation has and is changing, and is hopefully changing for the better … I’ll be moving in the next week or two to get Ken Henry back before the Senate economics committee so we can get a reassessment of Australia’s position in the recession — how the global economy is going, and whether we do need to continue full-on with the rollout.

I could not find any media release from The Greens to this end, but the quotes do not distort what he said. The Green’s leader also intimated according the journalist that “he was concerned Australia might be accumulating unnecessary debt”.

So are The Greens still echoing those plaintively false neo-liberal foundations that define their current macroeconomic policy? I was hoping that they would withdraw that part of their policy until they had time to develop something that befits the sophistication of their environmental and social vision.

As an aside, I would welcome the Treasury boss and the central bank boss being called before a Senate committee to tell us all why they were not arresting the spiralling labour underutilisation. But of-course that is not what Bob Brown was concerned with in his interview yesterday. He seems to be getting sucked into the “debt is bad”, “debt is growing out of control”, “the economy doesn’t need any further stimulus” mania that the neo-liberals are now increasingly launching.

I especially hoped that The Greens would stop making ill-informed macroeconomic comments and help push the real economic issues which relate to joblessness and underemployment. The focus on budget deficit numbers and debt numbers per se is a sideshow. Don’t The Greens realise the crowd they were hanging out when they buy into that hysteria?

Anyway, back to the main message for today. At the G-20 Finance Ministers’ meeting just concluded in London, the IMF released the following statement – Rising Unemployment Marks Crisis Third Wave.

The conservative organisation, which has a long and sad track record of enforcing conditions on lending arrangement to various countries that have entrenched unemployment and poverty, is now arguing that:

Policy action to combat the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression is working, but governments should not relax stimulus measures until recovery takes hold and unemployment levels recede …

Note the wording carefully – until unemployment levels recede. First, recede doesn’t mean continued increase. Second, recede to what? The document released does not go into that which I thought was interesting in its own right. But the statement suggests that unemployment rates have to come off from their peaks before the governments should relax their stimulus packages.

IMF Director Dominique Strauss-Kahn told a press conference at the G-20 meeting that:

We are seeing the third wave of the crisis, which is rising levels of unemployment … The first two waves were the financial crisis and the consequent global economic crisis. Imagine the worker in Germany or France who will lose his job in the months ahead. For that worker the crisis is not behind him, but still ahead …

The IMF claim that the main aim is to avoid jobless recovery. In that vein while the IMF still believes, mistakenly, that the fiscal positions are unsustainable (see speech the IMF director’s September 4 Bundesbank speech), they are arguing at present that:

… policymakers should err on the side of caution as they decide when to exit from their crisis response policies, although governments should develop their exit plans now so that they are able to build public support and act when the time is right … [the G-20 ministers] … all recognized today that even if we need to discuss our exit strategy, it’s not the time to implement it. It’s time to go on supporting demand until private demand is strong enough so that public demand can be reduced …

In its most recent report on Australia, the OECD in July said that:

The international crisis has not spared Australia, even if its impact will be less severe there than the OECD average. Weaker foreign demand and its repercussions on the domestic economy are expected to pull down GDP by ½ per cent in 2009, followed by growth of only 1¼ per cent in 2010. In this difficult climate, unemployment could rise to almost 8% by late 2010, while inflation should decelerate. To mitigate the impact of the crisis, the authorities need to maintain the expansionary thrust of their economic policy. Monetary policy could be loosened further. The infrastructure development programme announced in the 2009-10 Budget is welcome and should strengthen fiscal policy impact. To enhance future growth potential, the reform of infrastructure regulations should continue, in particular to ensure regulatory streamlining between States.

So two major world organisations, both cut with the neo-liberal cloth have recommended continued stimulus.

The IMF released a report recently with their latest analysis of the Australian economy. While it was released in August, the information used is at July 22, 2009.

The section on “The Effectiveness of Fiscal Stimulus Measures” contains some interesting scenarios, although given that they are based on the IMF’s Global Integrated Monetary and Fiscal Model (GIMF), one shouldn’t get too over-excited by them (in terms of accuracy). At least the GIMF has non-Ricardian features built into it which actually allow net spending increases to stimulate the private economy.

But then the government budget constraint component of the model allows for crowding out and the public debt-GDP ratio is a key stabilisation constraint. So, in general, GIMF is not a model that has much to do with the way the fiat monetary system operates or the conduct of fiscal policy within that monetary system.

However, as you will see later, the numbers produced do allow us to consider some experiments based on estimates that the conservatives are producing.

First, in relation to the scenarios, does fiscal policy design matter? Various uniformed neo-liberals keep arguing for tax cuts whereas modern monetary theorists value the direct impact of government spending, particularly on employment creating infrastructure. In this context, the IMF modelled a “temporary (one-year), one-percent-of-GDP increases” in a range of fiscal instruments. They concluded that:

The results … illustrate that direct government spending has the largest impact on aggregate demand with both government consumption and investment expenditures having multipliers larger than one. Transfers targeted to low-income (liquidity-constrained) households and reductions in value-added taxes have the next largest effects. Reductions in taxes on labor income and transfers to all households have small and similarly-sized multipliers while reductions in taxes on corporate profits have essentially a zero multiplier.

While the way they generated these results is disputable, they are in line with the sort of estimates you would get from any reasonable non-Ricardian model. Which all goes to say that the conservative “tax cutting” agenda would not be a suitable approach to fiscal stimulus. Of-course, they advance that agenda to reduce the role of government and expand the role of the private market.

Second, the IMF notes that the fiscal responses or multipliers (that is, how much GDP growth do you get per $1 of stimulus) are not independent of how the central bank behaves. So if “monetary policy does not initially respond to the higher inflation resulting from the fiscal measures, the impact on GDP increases by a nontrivial amount”.

You can see that the GIMF ultimately believes fiscal expansion will be inflationary. That is in-built into the model and reflects its largely mainstream roots. The reality is that while expansion may lift prices from their recessed levels back to more normal levels (which reflect profit margin targets etc), this is not what we call inflation.

It is only when nominal spending growth outstrips the real capacity of the economy to absorb it do you get inflation. That is not inevitable and not likely in the medium-term given the significant unused productive capacity and the very high labour underutilisation rates that are current.

Anyway, the results of their simulations provides the following Table (which appears on Page 5 of their Report). They introduce the table with this statement:

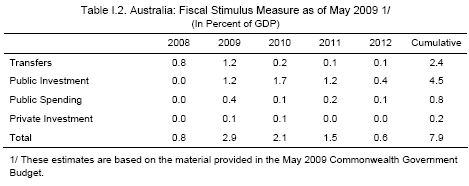

Table I.2 presents a breakdown of the measures that are heavily focused on public investment and transfers to low- and middle-income families, measures that the multiplier analysis suggests should be highly effective at stimulating activity.

So the total impact of the stimulus packages to date put an extra 0.8 per cent spending (as a percentage of GDP) in 2008, 2.9 per cent in 2009, 2.1 per cent in 2010, 1.5 per cent in 2011 and 0.6 per cent in 2012. The cumulative contribution to GDP over that time horizon is 7.9 per cent of GDP.

But that only takes into account the $ net spending injections. The next part of their analysis models the total impact once the spending multipliers have worked their way through the system. So $1 of government spending on goods increases output of those goods by $1. The workers are paid and then, in turn, spend some part of that $1 overall. That feeds back into the system and so on. That is the nature of the spending multiplier.

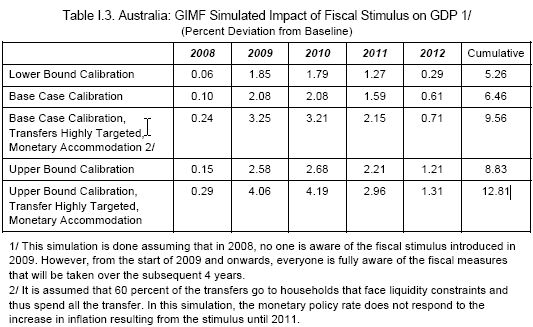

The results of the IMF simulations are produced in Table 1.3 (which I reproduce below). The Table shows that the fiscal stimulus will result in cumulative GDP being around 10 percentage points higher over the 5 years than otherwise. The different rows in the Table reflect the various scenario assumptions that were used which I won’t go into.

The IMF conclude that:

It is probably reasonable to expect the impact to be close to that achieved under the base-case calibration with monetary accommodation and highly targeted transfers, which would bring the cumulative impact over the five years close to 10 percentage points of GDP.

Given the IMF is now saying we should focus on unemployment, we might have expected some reaction from the G-20 Finance Ministers meeting. The problem is that the G-20 ministers seem to have a dysfunctional vision about how to address the unemployment issue.

This list of 92 Action Items form the basis of their on-going understanding as to what happened and their commitment to responding to the crisis.

You can search the entire 92 Action Items spread neatly across 23 pages and you will not find a single reference to employment, unemployment or underemployment. Apparently, the labour market is not part of the macroeconomy. They do say (Action Item 4) that they will:

… commit today to taking whatever action is necessary to accelerate the return to trend growth and we call on the IMF to assess regularly the actions taken and the actions required.

Further, in the final G-20 Communiqué endorsed by the Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors in attendance at the meeting you will similarly read nothing about the labour market.

However, we learn from the IMF that the G-20 governments will:

… endeavor to combat joblessness by promoting employment through structural policies, active labor market policies, training and education.

So obviously there has been discussion and the only vision they have is the continuation of the failed supply-side policies. These policies have their genesis in the erroneous idea that individuals are to blame for their own circumstances (which include labour market outcomes). There is a denial that unemployment arises due to systemic failure of the macroeconomy to produce enough jobs. There is a denial that unemployment is an involuntary state that the individual can do very little about.

If there are not enough jobs then all the training in the world just shuffles the unemployment queue. Supply-side measures create zero jobs and the way they have been implemented in Australia they amount to pernicious attacks on the most vulnerable persons within our communities and waste billions of public dollars.

The depressing fact is that the narrow window of opportunity to re-define the employment agenda is disappearing as the neo-liberals regain command of the policy agenda after being shaken to the foundations by the crisis.

Somehow, these characters feel that can now walk back in the streets with their heads held high and deliver more of the same that caused the crisis in the first place. They are actually confident that we will go along with it. The problem is that we will. More the fool us.

When mainstream economics as a knowledge system and the profession who disseminates that “knowledge” have both failed at the most elemental level to understand that basis of the crisis it amazes me that the proponents of the paradigm are without shame.

Some simulations on fiscal withdrawal

Based on the IMF update discussed above, I decided to experiment with some simulations of my own to put some numbers next to the key policy objectives.

The framework I used was a derivative of Okun’s Law, which provides a workable rule of thumb (that regular readers will have seen me use before) to assess the impact of growth on unemployment.

The rule of thumb is that for the unemployment rate to remain constant (that is, no change up or down), real GDP growth must equal the sum of labour force growth and labour productivity growth.

I am assuming that labour force growth is 1.8 per cent per annum which is about right. It does fluctuate but not by much.

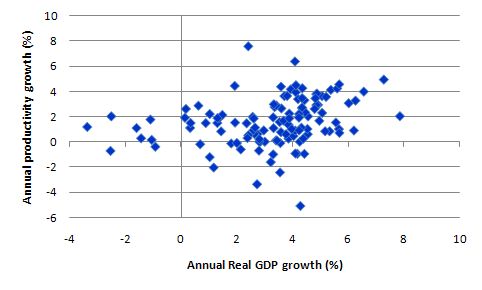

What about labour productivity growth? The following graph shows you what the relationship between labour productivity growth (GDP per hour worked) and real GDP growth looks like. It is based on ABS National Accounts data and observations from September 1979 to June 2009.

The point is clear that as economic growth gathers pace, labour productivity will also rise. So that fact has to be included in our thinking. I am assuming that labour productivity growth is 1 per cent in 2010 (with the stimulus applied), 1.5 per cent in 2011 and 2 per cent in 2012. These are very conservative estimates. For the second simulation (without the stimulus) I assume that labour productivity growth remains pitifully flat at 0.5 per cent per annum throughout. Again these are very conservative estimates.

The lower the assumed productivity growth the lower will the rise in unemployment as a result of the sluggish economic growth.

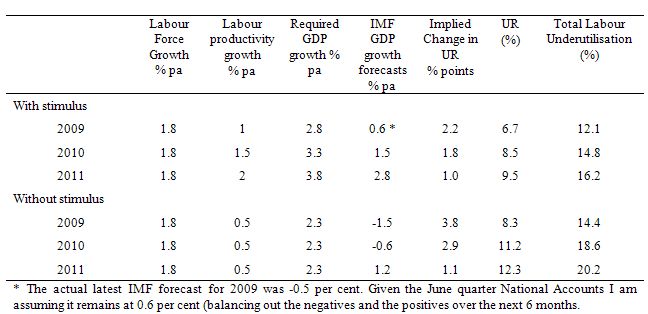

The following table shows the simulations. The top half is what the forecasts would be with the stimulus packages intact.

Column (3) shows the Required GDP growth rate (which is the sum of the labour force and labour productivity growth rates). It is the rate that the real economy has to grow to keep the official unemployment rate from changing.

Column (4) shows the GDP growth estimates. I used the IMF growth forecasts for Australia for 2010 and 2011 which were 1.5 per cent and 2.8 per cent, respectively. They have forecast 2009 would be -0.5 but events appear to have overtaken that and so I have assumed the June quarter result persists throughout the year. I don’t see the growth rate getting much beyond that in the second-half of 2009.

Column (5) then applies the rule of thumb above to show what impact the GDP gap (Required GDP growth minus estimated GDP growth) has on the unemployment rate. So in 2009, GDP growth at 0.6 per cent is 2.2 per cent below what it has to be to keep unemployment from rising. Column (6) then shows the unemployment rate as a consequence of the GDP growth gap.

I then modelled the relationship between the unemployment rate and the total labour underutilisation rate (using CofFEE Labour Market Indicators data). Column (7) thus shows what the broad labour underutilisation rate (sum of unemployment, underemployment and hidden unemployment) would be under the GDP growth scenarios.

The bottom half of the Table shows what would happen without the stimulus packages using the IMFs multiplier assessments discussed above. So, for example, in 2009 if GDP growth remains at 0.6 per cent but the stimulus package is responsible for 2.08 per cent growth, then the without stimulus growth would have been -1.5 per cent and so on.

Note that given the growth path is considerably worse without the stimulus packages I assume very flat productivity growth (0.5 per annum throughout).

This experiment then allows you to see what impact the two scenarios have on the labour market. In both case, unemployment and broader labour underutilisation continue to rise. But without the stimulus we are looking at 1991 outcomes. Even with the stimulus we will go beyond 16 per cent total labour wastage.

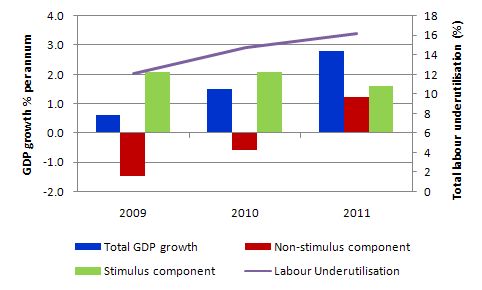

The following graph just decomposes the forecasted GDP growth performance into stimulus and non-stimulus effects to provide another perspective on the information presented in the Table. The line graphed is the evolution of the broad labour underutilisation estimates with the stimulus maintained. Clearly the current stimulus is deficient. More is needed to go close to achieving reasonable labour market outcomes.

It is clear that this work is experimental and subject to a lot of assumptions. But the calibrations are not that far off what happened in 1991 that I think they are worth reporting to condition the debate somewhat.

Conclusion

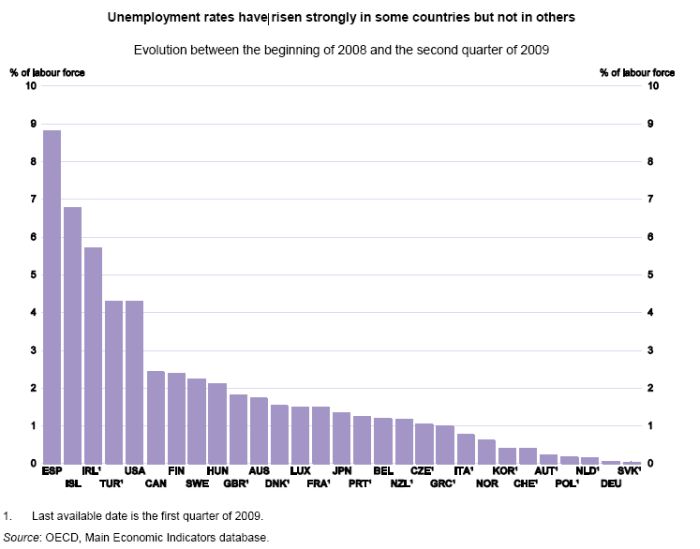

To put our so-called miracle economy into some perspective this graph from the OECD is sobering. It shows the change in the official unemployment rates (in percentage points) from the start of 2008 until June 2009 (although for some countries denoted with a 1 sub-script the data is for the first quarter).

You can see that Australia is somewhere in the middle. And remember this doesn’t take into account the sharp rises in underemployment in Australia which are probably worse than in most countries. I am looking into an international comparison of this at present and Australia is one of the worst performers with respect to underemployment. More on that later.

The message is clear. Even though we have avoided a “technical recession” our labour market is in poor shape and needs urgent attention.

I wonder how much modelling the Opposition and the right-wing think tanks have actually done on these issues?

All the evidence and new data is telling me we need further stimulus to push GDP growth harder to make sure unemployment does not continue to rise.

But if the statements coming from the G-20 Finance ministers are any guide we will be disappointed. And the we will include millions who are not able to get work (or enough of it) because the system has failed to produce enough work and the governments have failed to see what their true responsibilities are.

Your scatter plot of productivity growth vs GDP growth doesn’t really look to me like any kind of correlation at all (i.e. it seems pretty random). Have you run a regression through it to quantify the actual strength of correlation between productivity growth and GDP growth, and the magnitude?

Dear Andos

Very slight positive relationship only. But the chart is productivity per hour worked. The rule of thumb is based on per person worked and that relationship is much stronger. The assumptions I used are very conservative.

best wishes

bill

In this Crikey post, Sinclair Davidson also looks at the change in unemployment in Australian and around the world, but concludes that it shows that the stimulus is not what has helped Australia’s economy. Somehow, I prefer the IMF analysis.

Dear Sean

The particular blog you linked is an example of specious reasoning at it best. No analysis is provided of the design and timing of the fiscal stimulus packages in the respective countries discussed. Austrian economics at its best!

While I do not agree much with the IMF, the GIMF model is managed by a person I have a lot of respect for. The results are consistent with other model structures including my own CofFEE-1 model and so are believable. At least they have decomposed the stimulus package and modelled the differential outcomes accordingly.

best wishes

bill