I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

How much difference do the GDP forecasts make?

Some readers of yesterday’s blog – Why we need more fiscal stimulus, noted that I used IMF estimates of the real GDP growth over the next three years, which have been criticised for being too pessimistic relative the the RBA and the Treasury. They asked me to briefly summarise what the difference would be to the projections if the more optimistic RBA and Treasury forecasts were deployed. This short blog shows you that it doesn’t make much difference in terms of the evolution in unemployment and total labour utilisation. It is all bad.

In early August the IMF put out revised estimates of real GDP growth for Australia (see yesterday’s blog) which suggested that they were more pessimistic about the health of the Australian economy than the RBA and the Federal Treasury.

The Government reacted and claimed that the IMF was being too pessimistic and had failed to take into account the improving demand for commodities from Asia and rising population growth.

They reiterated that the budget forecasts were solid in their view – that is, that the economy would grow by 2.25 per cent in 2010-11 and by 4.5 per cent in 2011-12.

The week before the RBA had upgraded its growth forecasts and were more in line with the Treasury position.

So how much difference does this all make?

You should read back over yesterday’s blog for methodology. I wouldn’t put too much store in the following analysis although I think it is indicative.

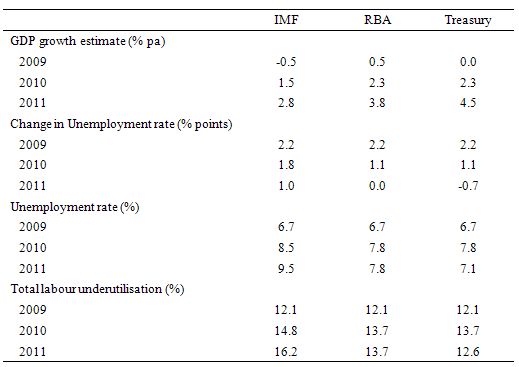

This Table captures the impact of the three different real GDP growth forecasts for 2009, 2010 and 2011 that are out there from the IMF (analysed yesterday), the RBA and the Treasury in the budget papers. For 2009, I have adjusted the GDP growth forecasts to 0.6 per cent given that they appeared to be overly pessimistic. The analysis is based on the actual froecasts for 2010 and 2011 though.

Remember that GDP growth has to be at least equal to the sum of labour force growth and productivity growth if the unemployment rate is to remain unchanged (approximately). The assumptions for the underlying growth rates are in yesterday’s blog.

What you see is that by the end of 2011 (FY), the unemployment rate and broad labour underutilisation rate (sum of unemployment, underemployment and hidden unemployment as a % of total labour force) continue to rise under the IMF estimates, are static under the RBA estimates and fall modestly under the Treasury assumptions. In my view the 4.5 per cent real GDP growth assumed by the Treasury for 2010-11 is overly optimistic.

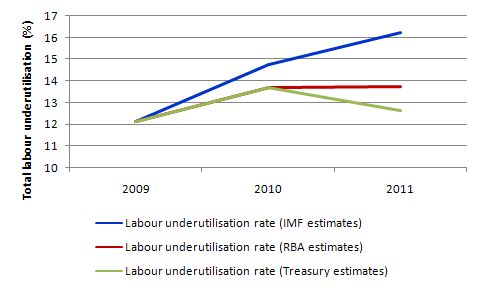

The following graph just plots the broad labour underutilisation rates the three scenarios (derived from the last column in the Table).

Whichever set of forecasts you accept the fact remains that even though GDP does not enter a technical recession under any of the scenarios, the labour market deteriorates significantly and remains in a parlous state after the pace of output growth quickens.

Conclusion

In my view, GDP recovers soon enough even out of a major downturn. It might take several quarters but it recovers.

The labour market, where people are, takes years to get over the damage caused by an economic downturn. The most efficient strategy any government can adopt (ignoring the personal and social issues) is to stop the labour market deteriorating in the first place. The costs of entrenched labour underutilisation are huge – lost income, increased poverty, strains on families, increased crime and the rest of it.

I can never understand how the neo-liberals can advance policies that deliberately extend the labour market crisis. It is counter to everything else they say about efficient resource allocation.

So even if these simulations are somewhat inaccurate – which they will be – they will not be several percentage points off the true outcome by the time we get there.

They unambigously point to the need for a third stimulus even if you adopt the overly optimistic future advanced by the Treasury. The government has to eat into the rising labour wastage now – rather than later.

All that is stopping the government from doing that is the misconstrued conception that they have adopted about how the fiat monetary system operates. There is no issue about the size of the budget deficit per se. But there is an issue about the level at which you allow the unemployment rate and the labour underutilisation rate to rise to.

This Post Has 0 Comments