These notes will serve as part of a briefing document that I will send off…

Krugman’s cockroach views on Brazil and hyperinflation

Today, I am publishing a special guest post from four authors working in the Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) tradition about inflation in Brazil. They are examining recent claims by Paul Krugman that the Brazilian experience ratifies basic Monetarist theory that links excessive monetary expansion with inflation (and hyperinflation). It turns out that the reality is quite different which is no surprise when it comes to confronting Krugman’s assertions with facts. Over to Daniel and co …

The Authors

Daniel Negreiros Conceição is a professor of Public Planning at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro.

Fabiano Dalto is a professor of Economics at the Federal University of Paraná.

Caio Vilella is a PhD student of Economics at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro.

Fadhel Kaboub is a associate professor of economics at Denison University and president of the Global Institute for Sustainable Prosperity.

Krugman’s cockroach views on Brazil and hyperinflation

In a recent article in the New York Times (May 13, 2021) – Krugman Wonks Out: Return of the Monetary Cockroaches – Paul Krugman rejected the old Monetarist view that changes in the money supply cause inflation, and pointed to the available 40 years of data as his overwhelming evidence against that view.

He denounced the resurgence of Monetarism as a case of:

… cockroach ideas, false beliefs that sometimes go away for a while, but always come back.

Paradoxically, after giving such a powerful critique of the idea that increases in the stock of money cause inflation, Krugman changes course and embraces the very “cockroach idea” he had so forcefully attacked, albeit in only one particular case:

To be fair, printing large amounts of money to pay government bills does in fact lead to high inflation. See the example of Brazil in the early 1990s.

According to Krugman, 1990s Brazil is supposedly a rare instance in which the “cockroach idea” did apply.

This is simply wrong.

Fallacious ideas, such as the Monetarist – Quantity Theory of Money (QTM) – are fallacious because they violate logic.

They never apply anywhere, even when the evidence appears to support it.

Krugman points to the verifiable correlation between inflation and the percent change in the amount of means of payment in a broad definition, M2, as evidence for his claims that Brazilian inflation in the 1990s was caused by too much money being printed by an over-spender government.

However, in this document – Programação Monetária 2019 (Portuguese) – Brazilians define M2 as M1 plus highly liquid private securities.

M2 does not include government bonds and, therefore, it is not evidence that the government was “printing money to pay for its bills”.

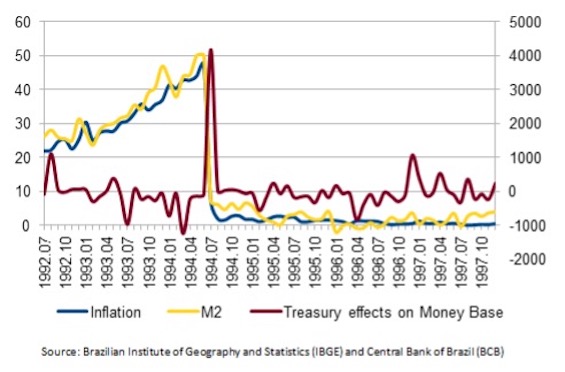

In fact – as the next graph shows – when we look at the public purchase of goods and services and the collection of taxes, the effects from Brazil’s Treasury operations on the monetary base are insignificantly or even negatively correlated with consumer price inflation, even during periods when the Brazilian economy was experiencing hyperinflation (1988-1994).

Furthermore, as Krugman should have known, money creation is not an alternative to debt-financing when it comes to the national government.

Central governments always create more money when they pay for goods and services, and when they make interest payments, amortisations, etc.

That is because government payments always increase the so-called monetary base, as reserves are transferred to commercial banks, and the quantity of money, as commercial banks credit the bank account of the recipients of the government payments.

If the QTM were true, we would observe inflation rising with every single payment by the government and inflation falling with every single tax payment to the government.

In fact, we should also see prices rising with every loan given by a commercial bank, and inflation falling as people make payments to their banks, since those are also instances of money creation and destruction.

The truth of the matter is that monetary aggregates do not create inflationary pressures by themselves.

Demand-driven inflation comes from growing demand, which results from the spending decisions of economic agents.

Some of these decisions may cause money to be created (for instance, when people or firms rely on bank loans to spend) and other decisions simply cause the existing money stock to switch hands.

What really increases demand is for people and governments to become more willing and able to spend.

This may lead to rising prices if supplies are insufficient to match the rising demand, and it may also lead to increases in the supply of money, if banks give out more loans and the government deficit spends.

Thus, causality is not from money to prices, as James Tobin famously warned.

A short note from Bill

The article by James Tobin is – Money and Income: Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc? – – The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 84(2), May 1970, 301-317.

In that article, James Tobin wrote:

Milton Friedman asserts that changes in the supply of money M (defined to include time deposits) are the principal cause of changes in money income Y …

Excessive money balances, for example, are not immediately absorbed by mammoth spurts of money income. They are gradually worked off – affecting interest rates, prices of financial and physical assets, and eventually investment and consumption spending …

Therefore it … [Friedman’s theories] … cannot have those clearcut implications regarding monetary and fiscal policy with which Professor Friedman has so confidently identified himself.

Even if we were to accept that inflationary pressures were caused by excess demand in 1990s Brazil, causality would still have gone from overall spending decisions to prices and then to the money supply.

However, 1990s Brazil was never your simple textbook case of “too much spending driving prices”.

Since the 1980s it has been well known by those who carefully study inflation that the Brazilian hyperinflation – as in 1920s Germany and most other countries that experienced explosive cases of inflation – was the result of an external debt crisis in which external debt payments kept relentless pressure against the exchange rate, even as the price of foreign exchange exploded.

For a country so highly dependent on key imports (refined oil, capital goods, electronics, etc.) and with prices as closely indexed to the exchange rate as 1990s Brazil, the impact from each and every global dollar shortage episode was unavoidably inflationary and explosively self-reinforcing.

Incidentally, the peaks of inflation and M2 depicted in Krugman’s chart coincide with the implementation of the Real Plan (from February to July 1994), when the government’s net expenses actually grew at a slower rate than the supply of money.

It was mainly the creation of private/bank money that kept fueling the rise in M2.

Yes, the government did contribute to the automatic expansion of the money supply by basically indexing the return on highly liquid bank deposits to the rate of inflation.

But even though M2 and inflation moved very closely together largely as the result of inflation-yielding bonds issued by the Brazilian government – which in turn allowed banks to offer inflation-yielding deposits included in M2 -, this was not because the government needed to finance its deficits, but simply because it chose to keep the politically influential owners of liquid wealth from losing purchasing power by giving them the opportunity to invest in risk-free, close to perfectly liquid, inflation-yielding bonds.

As for the price stability achieved by the Real Plan, it was mainly the result of the exchange rate stabilization that followed Brazil’s foreign debt renegotiation in the first half of the 1990s, undesirably high unemployment and sluggish real wage growth, and the increased openness to imports which reduced the market power of domestic producers.

All these factors are quite unrelated to the behavior of the money supply.

Conclusion

In conclusion, “cockroach ideas” are a pest for any economic debate, and the monetarist idea that the money supply is exogenous and causes inflation is a “cockroach idea” that continues to infest Krugman’s mind when it comes to explaining Brazil’s experience in the 1990s.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2021 The Authors. All Rights Reserved.

There are a few who realise that the commercial banks are not conduits between savers and borrowers; who know that commercial banks do not loan out time deposits, nor the “proceeds” of time-deposits, nor or the owner’s equity, nor any liability item. The banks are not middlemen in the lending process for either depositors or stockholders.

It is axiomatic that the demand and time deposits in the commercial banks can only be invested by their owners, that time-deposits, basically, are demand-deposits with zero velocity, and that as long as any deposit, time or demand, has a zero velocity it quite obviously isn’t, nor can’t, be used to finance investment.

In other words, if the public chooses to hold savings in the commercial banks the funds are not being spent as long as they are so held-and the funds are, for the time being, lost to investment. An increase in bank CDs, adds nothing to N-gDp.

Both an increasing volume and an increasing proportion of all bank deposits represent savings/investment type of accounts (irrespective of the ability to draw drafts against this warehouse money). This destroys money velocity. That’s the very reason for low economic growth over recent years.Said

But the demand for money (cash balances) also has risen a lot, which means money’s velocity has been plummeting. Whereas velocity is the multiple of nominal GDP to the money supply, money demand is the inverse (the multiple of money supply to nominal GDP, or the reciprocal of velocity). Fast-rising money demand (fast-declining velocity) signifies hoarding.

Banks, businesses, and households tend not to hoard money in good times, or when they have confidence in the credibility and predictability of policymakers; they hoard in bad times, when they lack sufficient confidence.Purchasing power is determined – like the value of other goods – by supply and demand, never by supply alone.

Financial speculation, stoking asset bubbles, provides a relatively insignificant demand for labour and materials and in some instances the over-all effects destroy the economy. Compared to real investment, Financial investment is rather inconsequential as a contributor to employment and production. Only debt growing out of real investment or consumption makes an actual direct demand for labour and materials.

Income velocity, Vi, is a “fudge factor,” but the transactions velocity of circulation, Vt, is a tangible figure.

Vi is a residual calculation – not a real physical observable and measurable statistic.

Income velocity, Vi, is endogenously derived and therefore contrived (N-gDp divided by M) whereas Vt, the transactions’ velocity of circulation, is an “independent” exogenous force acting on prices.

Changes in velocity have nothing to do with the speed at which money moves from hand to hand but are entirely the result of movements between demand deposits and other kinds of deposits. Bank-held savings have a zero payment’s velocity. And all monetary savings originate in the banks. Banks do not loan out savings. From the standpoint of the entire payment’s system, the monetary savings practices of the public are reflected in the velocity of their deposits, and not in their volume.

A large proportion of the several Covid-19 stimulus injections represent inert funds. That’s how negative real rates, indeed negative nominal rates, are subsequently generated. Will their owners ever put them back to work, back into circulation? Only if their owners spend directly, or invest directly or indirectly outside of the banks.

Every time a bank makes a loan or the government spends this is by new money creation. Bank held savings remain frozen. Money products are inflationary. Savings products are non-inflationary. Money products decrease the real rate of interest. Savings products increase the real rate of interest. Money products decrease the exchange value of the currency. Savings products increase the exchange value of the currency.

There are over 16 trillion dollars in bank-held savings that are frozen. Banks don’t lend deposits. Savings are not synonymous with the money stock. Banks aren’t intermediaries. Money grows ex nihilo (out of nothing). Bank-held savings deposits are lost to both consumption and investment.Said

Bank-held savings destroy the velocity of circulation, economists don’t know a debit from a credit.The complete deregulation of interest rates (for just the banks, as the nonbanks were deregulated, since the GD and prior to 1966 impounded an increasing volume and percentage of all bank deposits. This is the reason for the fall in velocity since 1981 the end of the monetisation of time deposits. The remuneration of IBDDs exacerbates this backwards policy.

Which brings us to zero interest rates. Why are the time deposits not invested? Simply because the commercial banks are carrying on their balance sheet a liability that is owned by the nonbank public (not the commercial banks), that cannot be used unless the nonbank public decides to use it, and by definition it is not being used. You cannot write a check against it, the banks cannot use it, the public is not using it, so it is not being used. Consequently, banks began systematically, to buy their liquidity, instead of following the old-fashioned practice of storing their liquidity.It is obvious that money has no significant impact on prices unless it is being exchanged.

Thus, low interest will probably do the opposite of what they are expected to do. May induce people to hold onto their funds and not part with liquidity for such a small price. This will also tend to reduce the supply of funds and their velocity. Increase the demand for cash (see pandemic for details ). With the cash not being exchanged for goods and services even though the deficit is forever increasing to meet the non government sector savings desires. Thus everyone turning Japanese.

The right-wing narratives are allways underpinned by some kind of fudge.

There was the hyperinflation of the weimar republic, but then this was Germany after world war I, and that´s not quite similar to anything we have today, not even in Syria.

Then came Zimbabwe, but Robert Mugabe experiments don’t compare with anything else either.

They needed to come up with something else.

So they went after Brasil, to the post-dictatorship years.

The Collor de Melo years – the president who was worst than Mugabe.

The cockroaches are those who bring these bad examples, pretending they can be applied to everything else.

A species that include Krugman.

Just wait for the similar story on Venezuela, and watch their narrative change.

Right now, the corporate welfare is working for the elites, and they have to support it, but once the economy recovers, all the fearmongering about inflation will come back.

They came back allready in the EU.

As things stand right now, Paulo says, “the corporate welfare is working for the elites, and they have to support it, but once the economy recovers, all the fearmongering about inflation will come back.” Of this there is little doubt, as both Bill and Paulo note that the fearmongering is already happening; i.e., via Krugman & Co. But what happens if Covid comes back, if mutations spread from destitute areas of the world into “developed” countries, and these societies are again forced into a series of lockdowns? I can find little discussion of this plausible scenario. Is that because it would finally put the stake in the neoliberal heart, and our minds, elite and non-elite alike, remain locked into TINA?

“was the result of an external debt crisis in which external debt payments kept relentless pressure against the exchange rate, even as the price of foreign exchange exploded.”

What does “external debt payments kept relentless pressure against the exchange rate” means? If the BRL to USD wasn’t free (which wasn’t) then it was the government itself that was fixing the exchange rate, right? It means then that inflation was then a consequence of the actions the government took to fix the FX? If so, what actions were those? And how they led to hyperinflation? If the government was fixing the FX, how could it have exploded?

“For a country so highly dependent on key imports (refined oil, capital goods, electronics, etc.) and with prices as closely indexed to the exchange rate as 1990s Brazil, the impact from each and every global dollar shortage episode was unavoidably inflationary and explosively self-reinforcing.”

Explosively self-reinforcing? How so? Is this related to the foreign debt issue/FX I just asked?

I must confess I couldn’t understand much of this post. It seems to me that the explanation is too generic, metaphorical and superficial. But I could be just me…

I had the same reaction as André. The explanation sounds surface level to me. Maybe a follow up response from the any of the authors or any one else who fully grasped the post.

André, like in 1920s Germany, Brazil suffered what Keynes named “transfer problems”. When a country is obliged to transfer resources abroad, as were Brazilian and Germany case, you have no choice but constrain domestic demand to generate fx. Wages compression through fx devaluation is a way to do this as well as public retrenchment. So, fx devaluation, in turn, was a permament policy in the 1980s as a consequence of external debt transfer requirements. Nedless to say, fx devaluations pressured domestic costs, allowed higher mark-ups and hence lead prices upwards. I hope you have got it now. If you are interested, I have written a paper on it with detailed explanation. https://www.scielo.br/j/rec/a/swCTDnr4XBLqRVNyzCBsTKK/?lang=en&format=pdf

Paulo, the inflation scare is already well underway if Canadian and US press are any indication. One can scarcely open the Business pages (and the online versions) without being bombarded with inflation scare stories.

“There are a few who realise that the commercial banks are not conduits between savers and borrowers; who know that commercial banks do not loan out time deposits”

There are even fewer that realise that bank deposits once created never move anywhere. They just change hands.

They only disappear when used to reduce a loan asset the bank holds.

M1 virtually rises continuously and doesn’t tell the whole story.

To get a handle on the flow it is not easy. It is far more difficult than just excluding saving deposits. You need to measure the amount of savings in M1 and then subtract that figure from M1.

We can’t go around asking everyone how much savings they have in their demand deposits. Try and estimate it by other means.

Some people have managed to do that and provide a corrected flow. It is not perfect but better than what is currently on offer.

Fabiano Silva, thanks, I will read the paper. Usually blog posts cannot be as complete and detailed as academic papers.

“They only disappear when used to reduce a loan asset the bank holds.”

Neil, they also disappear when taxes are paid.

You can only get the result the inflation crowd cry about if you make unrealistic assumptions using the QTM formula.

For the life of me, economists willingness to do that always surprises me (but also not surprising).

“You need to measure the amount of savings in M1”

It’s *all* savings in M1. It wouldn’t be there otherwise. Which is why monetarist dividing lines are not in the least bit useful.

“Neil, they also disappear when taxes are paid.”

It’s the same process. It reduces a loan asset that the bank holds. There’s nothing particularly special about paying taxes. In the grand scheme of things it’s just another loan repayment that reduces the size of the balance sheet.

It may be a special forced loan asset at a variable externally imposed interest rate, but it is still functionally a loan asset.

Neil,

As you know none of these guys are monetarists. I’ve shown you their work before. They have figured it out. Some are MMT’rs for over 20 years. Certainly not Austrians. Alan Longborn is one of them a long time Australian MMT’r.

You know their views..

1) “Money” is the measure of liquidity; the yardstick by which the liquidity of all other assets is measured;

(2) Income velocity is a contrived figure (fabricated); it’s the transactions velocity (bank debits – Vt) that’s statistically significant (i.e., financial transactions are not random). However, the G.6: Debit and Demand Deposit Turnover (longest running Federal Reserve statistical release up to that point), was discontinued in Sept. 1996 (money actually exchanging counter-parities within the payment’s system).

(3) N-gDp is a by product or proxy, of monetary flows, M*Vt, (or aggregate monetary purchasing power), i.e., our means-of-payment money, M, times its transactions rate of turnover, Vt. N-gDp ≠ AD as Keynesian economists define it.

(4) The rates-of-change, Roc’s (∆) used by economists are specious (always at an annualised rate; which never coincides with an economic lag).

(5) Milton Friedman became famous using only half the equation (the means-of-payment money supply), leaving his believers with the labour of Sisyphus;

(6) Contrary to economic theory, & Nobel laureate, Dr. Milton Friedman and Anna J. Swartz (“Money and Business Cycles”), monetary lags are not “long & variable” (A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960, published in 1963).

The lags for monetary flows, M*Vt, i.e. the proxies for (1) real-growth, & for (2) inflation indices (for the last 100 years), are historically, mathematical constants. However, the FED’s transmission mechanism, its target (pegging interest rates), is indirect, varies widely over time, and in magnitude. What the net expansion of money will be, as a consequence of a given injection of additional reserves, or change in policy rates, nobody knows until long after the fact. The consequence is a delayed, remote, and approximate control over the lending and money-creating capacity of the banking system;

(7) Roc’s in M*Vt are always measured with the same length of time as the specific economic lag (as its influence approaches its maximum impact (not an arbitrary date range); as demonstrated by the clustering on a scatter plot diagram;

(8) Not surprisingly, the companion series, non-seasonally adjusted member commercial bank “costless” legal reserves or “Manna from Heaven” (their Roc’s), corroborate both of monetary flows’ distributed lags — their lengths are identical (as the weighted arithmetic average of reserve ratios and reservable liabilities remains constant);

(9) Consequently, since the lags for (1) monetary flows, and (2) “costless” legal reserves, are synchronous & indistinguishable, economic prognostications (using simple algebra), are infallible (for less than one year);

(10) Asset inflation, or economic bubbles, are incorporated: including housing, commodity, dot.com, etc. This is the “Holy Grail” and it is inviolate and sacrosanct: See 1931 Committee on Bank Reserves Proposal (by the Board’s Division of Research and Statistics), published Feb, 5, 1938, declassified after 45 years on March 23, 1983.

(11) The BEA uses quarterly accounting periods for R-gDp and the deflator. The accounting periods for gDp should correspond to the specific economic lag, not quarterly (apples to oranges). Because the lags for gDp data overlap Roc’s in M*Vt, the statistical correlation between the two is somewhat degraded. However the statistical correlation between Roc’s in M*Vt, & for example, the bond market is unparalleled;

(12) Monetary policy objectives should not be in terms of any particular rate or range of growth of any monetary aggregate. Rather, policy should be formulated in terms of desired Roc’s in monetary flows relative to Roc’s in R-gDp;

(13) Combining real-output with inflation to obtain Roc’s in N-gDp, can then be used as a proxy figure for Roc’s in all transactions. Roc’s in R-gDp have to be used, of course, as a policy standard;

(14) Because of monopoly elements, and other structural defects, which raise costs, and prices, unnecessarily, and inhibit downward price flexibility in our markets, is it advisable to then follow a monetary policy which will permit the Roc, rate-of-change, in money flows to exceed the Roc in R-gDp by c. 2 percentage points ?

I still haven’t got my head around it all and I’ve been looking at it for over 2 years. When I showed you it you agreed that their seasonal inflection points make perfect sense. Happen around the same time every year.

To encourage debate and talk about it further.

Seasonal inflection points (they may vary a little from year to year):

Pivot ↓ #1 3rd week in Jan.

Pivot ↑ #2 mid March

Pivot ↓ #3 May 5th

Pivot ↑ #4 mid-June

Pivot ↓ #5 July 21st

Pivot ↑ #6 2-3 week in October

There are 6 seasonal, endogenous, economic inflection points each year. These seasonal factors are pre-determined, based on the distributed lag effect of money flows, by the FRB-NY’s “trading desk” operations, executing the FOMC’s monetary policy directives (in the present case just reserve “smoothing” and “draining” operations, the oscillating inflows and outflows, the making and or receiving of interbank and correspondent bank payments by and large using their “free” excess reserve balances).

Each and every year, the seasonal factor’s map (economic time series’ cyclical trend), or scientific proof, is demonstrated by the product of money flows, our means-of-payment money X’s its transaction’s velocity of circulation (the scientific method).

Monetary flows (volume X’s transactions velocity) measures money flow’s impact on production, prices, and the economy (as economic flows are driven by payments: bank debits to deposit accounts, principally thru “total checkable deposits”, as all payments clear thru the Federal Reserve System). It is an economic indicator (not necessarily an equity barometer). Rates-of-change Δ, in M*Vt = RoC’s Δ in AD, aggregate monetary purchasing power.

Thus M*Vt serves as a “guide post” for N-gDp trajectories.

N-gDp is determined by the volume of goods & services coming on the market relative to the actual, transactions, flow of money. RoC’s in R-gDp serves as a close proxy to RoC’s in total physical transactions, T, that finance both goods and services. Then RoC’s in P, represents the price level, or various RoC’s in a group of prices and indices.

Monetary flows’ propagation, are a mathematically robust sequence of numbers (sigma Σ), neither neutral nor opaque, which pre-determine macro-economic momentum (the →”arrow of time” or “directionally sensitive time-frequency de-compositions”).

For short-term money flows, the proxy for real-output, R-gDp, it’s the rate of accumulation, a posteriori, that adds incrementally and immediately to its running total.

Its economic impact is defined by its rate-of-change, Δ “change in”. The RoC, is the pace at which a variable changes, Δ, over that specific lag’s established periodicity.

And Alfred Marshall’s cash-balances approach (viz., a schedule of the amounts of money that will be offered at given levels of “P”), viz., where at times “K” is the reciprocal of Vt, or “K” has the dimension of a “storage period” and “bridges the gaps of transition periods” in Yale Professor Irving Fisher’s model.

As Nobel Laureate Dr. Ken Arrow says: “all analysis is a model”.

Note the 2019 seasonal decline in the deposits, the primary money stock (which should include the Treasury’s General Fund Account, but by an accounting mistake, doesn’t), where legal reserve requirements, i.e., account maintenance (complicit reserves), must be applied after the 30 day computation period; for the Pivot ↑ #4 mid-June. It is no happenstance that markets turn mid-June.

“When I showed you it you agreed that their seasonal inflection points make perfect sense.”

It only makes sense in the US where they have these wrinkles in their relatively primitive banking system. It’s not a systemic feature. It’s an artefact of the way the US does banking.

It does not apply in the UK, for example, where our basic bank account requirement ensures everybody has access to a bank account – which means there can be no deposit refusal overall and therefore no need for some of the extreme features of the US system.