I started my undergraduate studies in economics in the late 1970s after starting out as…

Negative interest rates – QE gone mad

On July 8, 2009 a world first occurred in Sweden when the Swedish Riksbank (its central bank) made announced that its deposit interest rate would be set at minus 0.25. While this has set the cat among the pidgeons around the financial markets, it is a classic example of “central banking gone crazy” or more politely “quantitative easing on steroids”. The only problem is that performance enhancing drugs seem to make athletes ride or run faster. This move will do very little to make the Swedish economy increase output or employ more people. For a background to my analysis on this event in central banking history you might like to read my blog – Quantitative Easing 101.

First, what does it actually mean? The rate of minus 0.25 means that commercial banks will now have to pay the central bank for positive reserve balances they hold at the Riksbank as part of the payments system. Up until recently reserve balances held overnight attract a “support rate” that could be zero (as in Japan and the US) or some positive rate (for example, in Australia the RBA pays 25 basis points below the target rate). Recently, in the face of the crisis, the US Fed relaxed this and now pays the funds rate (which is not much of a change given the funds rate is down to 0.5 per cent anyway.

In the Financial Times last week (August 30, 2009) Wolfgang Münchau wrote that:

The zero lower bound is one of the great myths of monetary economics. It is the statement that interest rates cannot fall below zero, for otherwise people would hoard cash. Generations of central bankers have treated it as the equivalent of zero degrees Kelvin, the lowest theoretically possible temperature.

So Sweden has exposed the myth. This has never been a myth to a proponent of what we might call Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) because the central bank can do what it likes with respect to the rate it charges or pays on reserves. It just means that the banks are now effectively fined for holding excess reserves.

So the question is why do this? Well the reason they are doing it is sourced in the fundamental misunderstanding of the fiat monetary system. You have to wonder how such a major ignorance could actually be perpetuated in the daily lives of central bankers in a not insignificantly educated nation such as Sweden. Anyway, Münchau summarises the intent as follows:

… the Riksbank hopes that by charging banks for saving their money, rather than paying them, it will encourage them to increase their lending to individuals and businesses, boosting the economy. It also hopes that it might encourage them to divert the money into other assets, such as government bonds or even highly rated corporate bonds. This would bring down bond yields and act as an stimulant.

The reasoning is a little more complex than this though. The interest rate being adjusted is a nominal rate (that is, how much money is changing hands) rather than a real rate (that is, what is the equivalent of the money changing hands in purchasing power terms). The real interest rate is the nominal rate minus the inflation rate.

The Swedish Riksbank has done this because real interest rates are out of whack with its inflation targets – there is very significant deflation occuring there as a consequence of the recession and nominal rates are not too high.

Before I return to the debate, it will help to have a look at some relevant statistics from Sweden.

What’s been going on in Sweden?

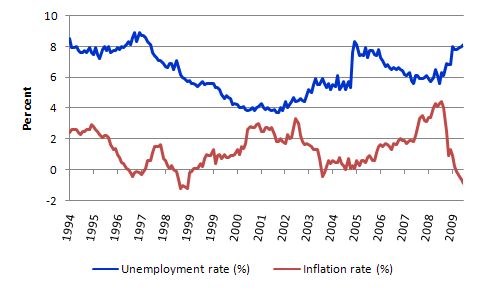

First, here is the relationship between unemployment and inflation in Sweden since 1994. You should compare this graph to the ones that follow (which show monetary policy adjustments) to convince yourselves that the Swedish Riksbank (an unelected body in a democracy) has targetted the jobs of its citizens in its fight against inflation. I don’t call that democracy or even sensible. But the RBA and other central banks do the same thing – that is what the neo-liberal policy era wrought!

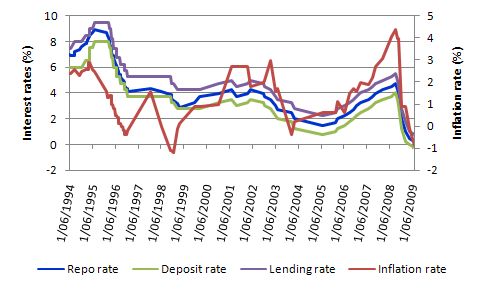

To let you see what the relationship between nominal and real interest rates means I produced a series of graphs showing the relation between nominal and real interest rates. The three rates of interest are defined by the Riksbank as:

The repo rate is the rate of interest at which banks can borrow or deposit funds at the Riksbank for a period of seven days.

The deposit rate is the rate of interest banks receive when they deposit funds in their accounts at the Riksbank overnight and is normally 0.75 percentage points lower than the repo rate.

The lending rate is the rate of interest banks pay when they borrow overnight funds from the Riksbank and is always 0.75 percentage points higher than the repo rate.

It is the deposit rate which is now set at minus 0.25 as at July 8, 2009.

The first graph shows the evolution of the three nominal interest rates since June 1, 2006 (left-hand axis) and the relevant inflation rate (CPI) (right-hand axis) at the date that the rates were adjusted by the Riksbank. I just made some continuous assumptions about the evolution of inflation and extrapolated accordingly. The assumption will not alter anything material but just allows me to assign inflation rates to the infrequent dates when the central bank made their monetary policy decisions.

You can see that the central bank has been obsessed with following the inflation rate religiously. Relate that back to the unemployment graph and you will see how monetary policy has deliberately used unemployment as a policy tool.

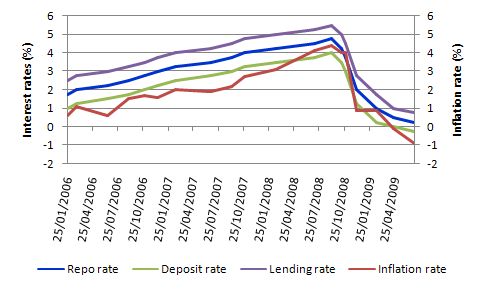

This graph just zooms into the previous graph from 2006 to show you more clearly the current relationship between nominal interest rates and inflation. You can see that the recession is deflating the economy so quickly that the nominal interest rates are now considered to be “too high” in the sense that real interest rates are rising above zero.

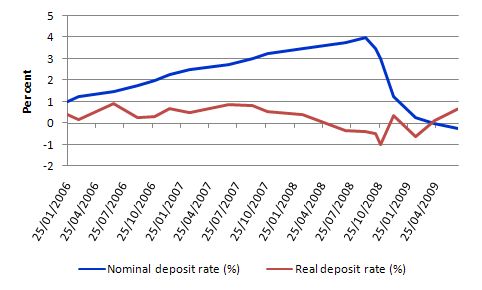

The following graph just presents the information from the previous graph differently to show you the evolution of the nominal deposit rate (blue line) and the real deposit rate (red line). As the nominal rate soared in their 2006-2008 tightening period, the rate of inflation was enough to keep the real rate at low levels and even negative from July 2008. However, as the recession has started to really scorch their economy, central bank monetary policy has been in a race against deflation and you can see that even though the nominal deposit rate is minus 0.25, the real rate is now positive, so the penalty they are imposing on the commercial banks is worse in real terms.

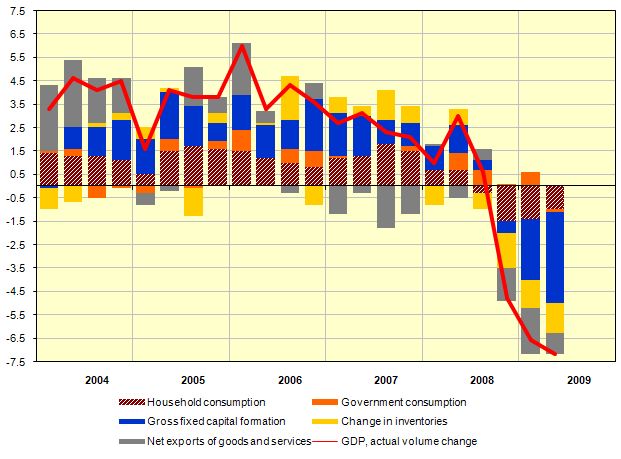

The final statistical chart is taken from the Swedish National Accounts and shows the contributions to change in GDP in percentages from 2004-2009 using quarterly data. As GDP growth has plunged since the fourth quarter 2008, fiscal policy has been all but absent. The way the Swedes present their national accounts data makes it had to disentangle government investment spending from total investment spending. So the blue bars capture all investment spending. It has severely shrunk in the last three quarters.

So apart from a small positive contribution in the first quarter 2009 (via public consumption spending), the graph shows you how little they are relying on fiscal policy to provide counter-stabilisation. In the current period, the government contribution to output growth is negative! This is neo-liberalism at its best! Not! Compare that to Australia’s current situation which I wrote about yesterday.

Back to the debate …

I thought it would be useful to put the data up to give you a feel for what is going on. Now back to the debate about negative interest rates. You can see from the graphs, that it was only the deposit rate that the Riksbank rendered negative. The logic of this move is as clear as it is stupid. The central bank wants to, in Münchau’s words:

… discourage banks to hoard their surplus liquidity in the form of central bank deposits, as opposed to lending it to customers. By cutting only the deposit rate below zero, the Riksbank only partially transgressed the zero lower bound. It used negative interest rates for the purpose of a highly targeted operation. Negative interest rates are therefore not an all-or-nothing proposition.

I hope everyone feels secure that not all rates were set below zero. Just in case you were feeling uncomfortable you can rest assured it doesn’t matter much either way.

There is a lot of resistance among central bankers to the negative interest rate idea. Some consider the small Swedish bank to be rather bolshie in its actions.

Some economists predict that a negative interest rate would force deposit holders to flee into cash. But this ignores the storage costs of holding money outside the bank (hired guns) and these are probably greater than 1 per cent of the cash value. So a minus 0.25 will not invoke that sort of behaviour.

Münchau’s assessment of why there is a song and dance going on about this is as follows:

… first … central bankers are a risk-averse lot and do not like to tread where no one has gone before … [second] … central bankers have also argued that negative interest rates would kill … money market funds. While that may be true, it is astonishing that its advocates prioritise the welfare of individual fund managers and their clients over the general goal of price stability. This is the argument of central bankers whose function is reduced to financial centre lobbyists.

A third argument is that zero or negative interest rates might lure investors into purchasing risky assets, in the full knowledge that those policies will sooner or later have to be reversed once the economy recovers. The latter is really an argument for a non-activist monetary policy, the kind that is generally preferred in continental Europe. But if non-activist policies result in large swings in inflation rates, they, too, might produce financial instability and unfair wealth distribution. So it is generally best for central banks to set interest rates to stabilise inflation expectations around a desired level, even if that requires vigorous policy action at times.

There is a long history of banks refusing to lend even though they have reserves. Japan’s experience between 2001 to around 2006 is a notable example. Then the government chose to use Quantitative Easing (keeping rates at zero though rather than negative – probably reflecting how conservative the BOJ is) but it was only fiscal policy that got the economy growing again and underpinned the confidence for investors to start approaching the banks to seek loans again.

Anyway, in reaction to the daring Swedish move, the current feeling is that other central banks will follow suit given their own banking sectors are also still not lending. So blindness to how a modern monetary economy is universal.

A so-called expert (an English investment banker) was quoted by the Financial Times last week as saying:

The success of the UK’s quantitative easing experiment hinges a lot on whether the banks will use the extra money they are getting for lending to individuals and businesses … If there is no sign of this over the next few months, then the Bank of England might consider a negative interest rate. In essence, it is a fine on banks that refuse to lend.

When will they ever learn and jettison this money multiplier nonsense?

The FT article further notes that:

In the UK, for example, nearly £140bn has been injected into the economy through central bank purchases of government bonds and corporate assets, mainly from the commercial banks. However, since the QE project was launched on March 5, a lot of this money, which in theory should be used by the commercial banks for lending to businesses and individuals, has ended up at the Bank of England in reserves.

They go on to argue that this increase in bank reserves could be used to “step up their lending to the private sector” because the more reserves it has the more they can lend.

This is basically nothing at all to do with the banking system in the UK or anywhere else for that matter. Banks do not lend because they have reserves. They get reserves because they have lent! Loans create deposits and then reserves are added.

The problem is that most of these commentators and central bankers have studied economics at universities which use textbooks such as Mankiw’s macroeconomics. Mankiw has written in recent months himself about negative interest rates – here and here.

The arguments are all gold standard, fixed-exchange rate, money multiplier, loanable funds doctrine nonsense. That is, not applicable to a fiat monetary system.

For example, in his private blog Mankiw has this gem:

If we want to prop up aggregate demand to promote full employment, what is the alternative to monetary policy aimed at producing negative real interest rates? Fiscal policy. Essentially, the private sector is saying it wants to save. Fiscal policy can say, “No you don’t. If you try to save, we will dissave on your behalf via budget deficits.” That fiscal dissaving would push equilibrium interest rates upward. But is that policy really welfare-improving compared to allowing interest rates to fall into the negative region? If people are feeling poorer and want to save for the future, why should we stop them? Unless we think their additional saving is irrational, it seems best to try to funnel that saving into investment with the appropriate interest rate. And given the available investment opportunities, that interest rate might well be negative.

So students – here is the mantra to take out into the real world:

(a) Budget deficits are evil because they cause inflation and deny the private sector the capacity to save.

(b) It is better to have negative interest rates to push funds into the hands of investors via the loanable funds market.

He earlier said that “Most ec 10 students begin thinking about the interest rate in terms of the supply and demand for loanable funds … There is no reason to presume that the equilibrium interest rate consistent with full employment is necessarily in the upper right quadrant of the Cartesian plane.”

This is the old classical doctrine that I discussed in this blog – The natural rate is zero!. It has no relevance at a macroeconomic level to the economy we live in.

You will readily appreciate that budget deficits by stimulating output and income also generate the capacity to allow the private sector saving desires to be met. The non-government sector cannot save if the government sector is in surplus. Impossible. Mankiw doesn’t even understand the basic national income relations that govern a modern monetary economy.

Just in case you need some help translating Mankiw’s writing you may want to have a look at this video, which is entitled Mankiw’s Ten Principles of Economics Translated – it will do the trick.

Currently, Adbusters is running a campaign against Mankiw’s brainwashing. They said:

You might not have heard of N. Gregory Mankiw. The Harvard economics professor and former adviser to George W. Bush is … one of the most effective and talented propagandists of our times. His target: young economics students. His field of operation: the world’s universities. His weapon: the best selling textbook in the world. It includes 36 chapters and 800 pages of nice colors, graphs, cool stories and interesting asides. Don’t worry if you or your kids don’t speak English, Mankiw’s text surely exists in your language.

The rest of that article is good reading for the layperson. Here is another snippet relating to my own research obsession – unemployment:

For Mankiw, if unemployment exists, it is only because of human inventions such as unemployment benefits, trade unions and minimum wages. Without them, there cannot be unemployment. Mankiw presents this view as being consensual among economists.

And this to emphasise the scale of the problem:

While Mankiw’s text is easy for professors to use, it oversimplifies economic theory and leaves out the ways in which markets can degrade human well-being, undermine societies, and threaten the planet. Each year, tens of thousands of students go out into the world, with Mankiw’s biases as a roadmap to the future.

Conclusion

The banks will not lend if there are no credit-worthy customers lining up for loans. The logic surrounding the negative interest rate move is based on the erroneous belief that the banks need reserves before they can lend. That is a major misrepresentation of the way the banking system actually operates. But the mainstream position asserts (wrongly) that banks only lend if they have prior reserves. The illusion is that a bank is an institution that accepts deposits to build up reserves and then on-lends them at a margin to make money. The conceptualisation suggests that if it doesn’t have adequate reserves then it cannot lend. So the presupposition is that by adding to bank reserves, quantitative easing will help lending.

But bank lending is not “reserve constrained”. Banks lend to any credit worthy customer they can find and then worry about their reserve positions afterwards. If they are short of reserves (their reserve accounts have to be in positive balance each day and in some countries central banks require certain ratios to be maintained) then they borrow from each other in the interbank market or, ultimately, they will borrow from the central bank through the so-called discount window. They are reluctant to use the latter facility because it carries a penalty (higher interest cost).

The point is that building bank reserves or penalising them for holding reserves will not increase the bank’s capacity to lend. Loans create deposits which generate reserves.

The reason that the commercial banks are currently not lending much is because they are not convinced there are credit worthy customers on their doorstep. In the current climate the assessment of what is credit worthy has become very strict compared to the lax days as the top of the boom approached.

The major problem facing the economy at present is that there is not a willingness to spend by the private sector and the resulting spending gap, has to, initially, be filled by the government using its fiscal policy capacity.

By appropriately expanding the fiscal position the government will not only add directly to aggregate demand and increase employment but will also promote confidence in the private sector that a recovery is possible. In turn, this will have the private investors lining up with their credentials to their local bank offices seeking funds for working capital and larger projects.

Fiddling with the real interest rate when it is already rock-bottom is just wasting time.

“However, since the QE project was launched on March 5, a lot of this money, which in theory should be used by the commercial banks for lending to businesses and individuals, has ended up at the Bank of England in reserves. ”

Ha. I wonder where else the FT writer would expect this money to end up? Into some kind of monetary ether?

Hi Bill

I took this one on myself on the KC blog a few times in July. Got a bit of a response from Sumner and some on his blog, but we were mostly talking past each other, claiming the other had misinterpreted, etc., so I let it go.

Basically, both the excess reserve tax (which is the negative nominal interest rate on excess reserves) and the currency tax of Mankiw are based on Yeager’s “money does not burn holes in pockets.” In seeing Sumner’s responses to me, he doesn’t think the money multiplier is the mechanism for the negative interest rate on ER, but rather that if you can push everyone holding short-term investments into deposits, then they will spend. The basic idea would be to have a negative rate on ER and a higher rate on RR, so that banks would be encouraged to convert ER to RR, not necessarily via lending, though, but instead by raising the relative return on deposits to other short-term investments. What you’d really get is a bunch of portfolio shifting, but no more spending, probably less at least from wealth holders since their returns fell (though some would argue the lower interest rate would bring about more borrowing, the net effect of borrowers and savers is less clear, as we know). For instance, in the US, banks would reclassify existing sweep accounts (about $800 billion right now) as deposits to raise RR relative to ER, but this would have no effect on depositors at all, who already think they are holding deposits.

An important point to bring out is that these folks (including some at the Riksbank) believe that setting the remuneration rate on reserve balances equal to the target rate is a tightening of policy, since it is believed that banks no longer have an incentive to “work off” ER either via lending (money multiplier) or the process I described above. So, the Fed’s move in the fall to pay interest on reserve balances was actually a tightening in their view that is more than partly to blame for the recession. They actually believe that in the US, banks desire to hold $700 billion in ER right now. Some at the Fed appear to believe this, too. Simply astounding!

Best,

Scott

Never knew that the loanable funds theory is so wrong!

I disagree with this article. Regardless of the ideological bent of mankiw et al, I seen no reason why negative nominal rates can’t stablise the eocnomy and employment as long as:

1. the negative interest rate charge to bank reserves gets passed on to their savers.

2. the negative interest rate is sufficiently negative

If you accept for a moment that the future is in general going to be a period of secular contraction due to demographics, wage arb and widespread and endemic income inequality, then I don’t see why negative nominal rates can’t have a place alongside fiscal policy in solving that problem.

Ultimately our civilisation is comprised of those who wish to transport wealth into the future and those who will offer to provide that service to them by borrowing today and paying back later. There is no other way of moving welath forwards in time since the physical output of the economy cannot be effectively stored.

If in future the amount of welath wishing to be transported forwards in time exceeds the productive borrowing capacity to meet that demand then people will need to accept a charge on saving. It is a nonsense to say that government can meet that entire demand by being the borrower of last resort since quite likely the policy of the government of the day will not be directed primarily towards metting the demand for saving, and secondly, there is no guarantee that the government will put the funds to better use at a nominal positive rate than a sensible private sector borrower accepting the same challenge at a nominal negative rate.

Sorry Bill, I must step in here on a small point.

The fact that prior reserves aren’t necessary isn’t necessarily proof that they’re not sufficient.

By that I mean that steroid doses of excess reserves, compensated at a negative rate, may have some small effect on bank asset acquisition behavior at the margin.

This would mostly likely be reflected in acquisition of risk free or near risk free assets at the margin. The negative interest rate on reserves would be arbitraged quickly to a negative rate on short dated treasuries. The interest rate arbitrage would dissipate as one moved further out the curve, due to interest rate risk.

I think this bank behavior would be limited. That’s because the rate effect would be arbitraged away very quickly due to the liquidity of the market in question. Also, bank reserve managers are intelligent enough to know they are dabbling dangerously in a zero sum game, given the central bank’s control over the level of aggregate excess reserves.

But I agree with you totally that any risky assets acquired must be justified by capital levels, not reserves. That’s the key, more integral point underlying all of this discussion.

So it’s a small point at the margin, in the case of risk free assets, but I think the logic that excess reserves aren’t necessary is a nearly but not entirely complete explanation of all potential behaviors.

A corollary to this is that one might argue the Riksbank is being reckless in actually encouraging bank asset acquisition behavior that may potentially conflict with prudent capital based lending, should the banks be tempted by frustration in that direction.

And a final corollary in turn is that one might argue the Fed is being RELATIVELY prudent by paying interest on reserves, in order to discourage the temptation toward the very counterproductive behavior the Riksbank may well be encouraging in its banking system. The fact is that the Fed has acknowledged the correct causality of reserves on its web site for a long time (i.e. the Fed supplies required reserves after the fact), so this explanation fits, in my view.

Dear JKH

And you can see your first point happening in the UK at present with yields on gilts falling as traders speculate whether the BOE is about to follow Sweden.

Good point about the Fed. The main issue as far as I see it is that it just places too much focus on monetary policy which is at a dead-end at present (zero or near zero rates) instead of using fiscal policy to do what it does best – put spending into the economy.

best wishes

bill

Dear Scepticus

Thanks for you comment. The main point of the blog was to note that monetary policy really isn’t the vehicle to be focusing on. I didn’t think the decision would be harmful – just irrelevant, although the points JKH an Scott make this morning are good.

On a small point, a major way to move wealth forward which we neglect is to provide solid education to all. Investments in human capacity are the most enduring of all.

It is technically obvious that the government can meet all the nominal spending gap (defined as the shortfall in nominal spending required to fully utilise all real resources) today and tomorrow and forever if it was politically viable to do so. That is not a nonsense at all. Further, it can borrow whatever it likes because it has no risk of insolvency. The way the government meets the “demand for saving” (your term) is to ensure income growth. It can do that by ensuring aggregate demand is sufficient.

Remember that spending brings forth its own saving – that is the major difference to what is usually understood. The mainstream view is that there is a pile of savings that need a place to go and that pool provides the capacity to spend. It is the other way around – government spending (or private investment for that matter) stimulates demand which in turn generates income growth which in turn boosts saving and renders the desire to save by the non-government sector consistent with the level of demand required to maintain high levels of employment and output.

Further, the idea that the government “borrows” the saving pool to then spend akin to a private investor who has to finance his/her spending is not applicable to a fiat monetary system. Governments do not borrow to spend. They borrow to ensure that bank reserves are consistent with the target interest rate set by monetary policy – no matter what spin is put on the “borrowing” by the media and the government itself.

But I accept there is nothing to guarantee that government spending will not be wasteful. For example, the war in Iraq.

best wishes

bill

Bill, thanks for the response. I’m aware in general terms of the chartalist point of view, however I remain to be convinced.

You said:

“government spending (or private investment for that matter) stimulates demand which in turn generates income growth ”

I’m not sure that holds true under all scenarios – how about a thought experiment? Imagine it’s 2030. Populations are now declining rapidly in all western and most all developed and semi developed asian nations due the demographic transition. Some emerging economies are still expanding their population but have failed to generate robust domestic consumer demand.

It seems to me that when populations are falling aggregate demand must do so also, not just because the population is ageing but because there are less and less people who need things. I don’t see how government spending or any other spending can sustain demand in this scenario. Assuming a constant money supply it should be obvious that under these circumstances (in which the rate of population decline and age-ing outpaces per capita income growth) consumption in the future would be more expensive than consumption now, which strongly suggests negative interest rates,

You don’t have to believe in this scenario to argue it – if your assertions are correct then you could demonstrate how government spending would stimulate sufficient demand that a saver putting money away today would get at least the same amount back in real terms, on average, five, ten or twenty years down the line. You seem to be saying fiscal spending can always create growth, which may be true under historical parameters of population and resource usage expansion but quite likely not under future ones.

Peak oil and other doom and gloom issues can also be mooted to make the same argument, but I feel the demographic one is most appropriate since what we know today almost guarantees future falling populations, whereas peak oil remains open to debate.

Just to clarify, my point about negative rates is not a monetary one. I agree that if they are considered as an adjunct to QE they are rather pointless. My point is a far more fundamental one which comes down to questioning expectations that future growth, or even stabilisation at 0% growth can be maintained in the long term, and what that would mean for the relationship between saver and borrower.

I am interested in the economics of llong term secular contraction, which must, after a period of 300 years of expansion of population and resource exploitation must be considered a possibility. I’d like to think that even under these circumstances if well managed we might manage a good per-capita outcome, but that is not the same as aggregate growth, and has implications for interest rates.

JKH, negative rates need not induce overly risky behaviour if banks get back to doing what they are supposed to do which is base their business on the spread between deposit and loan rates. As long as banks pass the negative rates onto deposit customers at the appropriate rate I don’t see that a tax on reserves makes much difference to a prudently run bank.

The risk taking imperative is then transferred to savers, who would likely chose to invest in low risk assets like long bonds at perhaps very low +ve rate of return, which would enormously increase fiscal options. Of course to make this work some form of cash demurrage would be mandated.

Dear scepticus

Yes, nominal demand growth has to be related to the real capacity of the economy to absorb it. If you construct scenarios where the real capacity falls then of-course nominal demand has to be tailored accordingly. But a declining population and a declining need doesn’t negate the fact that what demand has to be generated can be generated by public spending if that is required to fill the saving desires by the non-government sector. If it gets harder and harder to consume (by which I guess you mean the population growth declines more slowly than the real resources available) then future consumption does get more expensive. We agree on that. How close we are to the point that real resources run out is something I am not qualified to speak on. Obviously, saving is a decision to command future real resources. Inflation can undermine that decision if it runs ahead of compounding. And so can the scenarios you paint.

What I am saying is that while there are idle resources, fiscal policy can create a demand for them. I am not pro-growth. Just full employment which is a different thing altogether. Modern monetary theory does not claim you can have infinite growth via net public spending. Repeat: nominal growth has to stimulate real capacity. If there is none, then there is no real growth.

best wishes

bill

Dear scepticus

I understand your point is not monetary and is rather related to projections of resource availability in the longer-term. It is a point that needs to be considered and is ignored by economists.

While not rendering that perspective unimportant, my emphasis also includes those who are unemployed and poor now and whose lives could be improved by appropriate fiscal policy use.

best wishes

bill

We agree completely that policy both fiscal and monetary should be tailored towards ensuring fairness of outcome for all and a smoothly functioning economy as the paramount objective.

I suppose my point is that under conditions of declining real capacity the fiscally driven demand you advocate would result in negative real rates, and from a socio-economic perspective I don’t see that as being much different to negative nominal rates. Both create a situation where for example saving for retirement in the mode to which we have become accustomed becomes untenable.

My fear is that negative real rates over a sustained period are more harmful than negative nominal rates if they create expectations of returns on savings which can’t be realised and society directs activity in the wrong direction as a result.

On that note I shall now retire to bed.

Scepticus 8:34,

You make an interesting point. It’s not clear to me that the Riksbank has imposed a penalty rate on reserves with the objective/expectation of spreading negative rates generally to deposit banking, but maybe I’ve missed something there. If that’s the case, then I suppose the banking system could preserve its spreads in doing so. Making deposit rates negative would be an escape valve for the kind of risk temptation I was referring to. But I’m not sure why depositors wouldn’t move immediately into central bank currency. The idea of being charged interest on deposits would not be psychologically appealing at all, and I expect many depositors would assume the risk of storing currency as a form of protest as well as monetary benefit.

I haven’t noticed much written about negative rates more generally, although I think Buiter did something quite elaborate a while back.

I think that one point missed in some of the discussion here (e.g. Scott’s remarks) is that, like Australia, Sweden does not have a minimum reserve ratio. The only requirement is that reserve balances are above zero. So, there is no distinction between an excess reserve rate (ER in Scott’s terminology) and the reserve rate (RR). Importantly, this means that lending and taking in new deposits will not reduce the size of the bank’s reserves attracting the 0.25% rate. In aggregate, the banks cannot do anything by themselves to reduce the total size of the reserve balances, regardless of how much or how little they lend (again highlighting the popular nonsense that banks are hoarding their reserves rather than lending them out). The only thing that would reduce these reserves in aggregate would be for the banks to engage in repo transactions with the central bank (earning +0.25% rather than -0.25%) as one bank lending their reserves to another bank does not change the aggregate reserves. Of course, this can still push market interest rates down as banks may need to buy additional bonds to provide as repo collateral to the central bank. But there is nothing special here about the fact that the deposit rate is negative. When the deposit rate was 0%, the repo rate was 0.50% and so banks still would have preferred to put as much of their reserve balances out on repo as possible rather than lost the 0.50%.

“The idea of being charged interest on deposits would not be psychologically appealing at all, and I expect many depositors would assume the risk of storing currency as a form of protest as well as monetary benefit.”

True, which is why buiter, mankiw, and tyler cowen recognised that some form of tax on cash would be needed, presumably reflecting the prevailing negative rate of interest on risk free assets.So if you took out 10K of savings to put into cash you’d only get 9900. You probably wouldn’t do that if there was a 0% or higher rate to be had a little further along the yield curve.

Having said that though, if everyone rushed to cash, cash would simply stop circulating, and there wouldn’t be nearly enough to go around. The problem would then be whether the real economy could operate properly without paper money. This also suggests that it might be sufficient just to withdraw all large denomination notes and replace them with coins and 1,5 dollar bills.

Of course plenty of people effectively have negative interest rates already, when they keep their money in transaction accounts that pay little or no interest but charge account keeping and transaction fees.

Bill,

Since we are speaking of Sweden, do you have any opinions (silly question!) on the work of economist Lars Svensson? He is on the board of the Riksbank.

Sean.

A tax on cash would disproportionately punish those with low balance, high velocity deposit and/or cash usage tendencies. These are the ones who can least afford to keep long duration (i.e. elevated) balances. Therefore the effective negative interest rate is much higher for them, due to the short duration nature of cash balances and the velocity of the cash penalty.

There’s a problem in charging an interest penalty on a financial asset of indeterminate or highly variable duration.

Dear Sean

I have never been impressed with his monetary economics. He was a foremost advocate for inflation targeting based on an underlying concept of a natural rate of unemployment. He has also written about the concept of Ricardian equivalence which basically says that fiscal policy may be hampered by the fact that public dis-saving (as he calls it) will be equally matched by private saving (in perfect anticipation) – so futile. In our recent book – Full employment abandoned we have a chapter or two where we provide an extensive critique of his work and that of his peers. His main solution to a liquidity trap is therefore not to rely on fiscal policy to boost public demand to replace the lack of private demand but to depreciate the currency so much you expand net exports. This is a highly contentious strategy and in my view would be ineffective. Certainly Sweden are not doing well in this regard.

I could go on.

best wishes

bill

Bill,

Is it fair to say that Ricardian equivalence is anathema to the modern monetary theory approach of net non government demand for saving?

Isn’t the problem with RE in this regard that it effectively treats the entire economy as a bond, with no growth?

(I.e. the equivalence of a deficit to the present value of future taxes ignores the growth in the tax base that a deficit may facilitate.)

Good point, Sean, regarding RR . . . I was mostly going after the US case and the arguments made by those in favor of an ER tax here, but, yes, even more ridiculous when applied to nations without RR.

Another point I made in my blogposts in July relates to Scepticus’ point about combining a reserve tax with a currency tax, which I have also heard before. The problem is that all of this is an attempt to reduce private saving, as if that’s the appropriate problem to fix. In the US, though, more, not less, deleveraging is precisely what the private sector needs right now. Far better to use fiscal policy to keep the economy at full employment and enable the private sector to do as it pleases in that regard right now. Further, as Minsky always explained, a non-govt sector with net saving is a far more stable macro arrangement over the business cycle and even longer, and the only way to achieve that is with a govt sector deficit. And, of course, the deficit doesn’t need to be incurred with govt “deciding where all the money will be spent,” as one could raise transfers or cut taxes and still enable the private sector to choose what to do with its income.

Again, though, it’s not clear to me that all these efforts at encouraging spending out of existing saving will work, anyway. First, we’re talking about people that were saving, and with these taxes on saving you’ve essentially cut their incomes, so their spending might actually be expected to fall. Second, what you’re really going to get from these proposals is a mammoth amount of portfolio shifting on the order of the early 1980s–as JKH says, the main impact will probably be on velocity, since the wealth holders don’t want to have refrigerators and car stereos now, they want to save, and they will try like mad to continue doing that while avoiding these penalties as much as possible. Third, as in the early 1980s attempts at targeting MS growth and where the relative benefits of holding deposits or cash and holding less liquid investments widened substantially, it’s highly unlikely that you could implement these proposals without financial institutions innovating to enable their customers to avoid these taxes while still holding fairly liquid balances. There would certainly be ample incentive for financial institutions to do so.

Overall, it’s not very well established that aggregate demand is all that interest sensitive, anyway. Certainly for firms, their capital investment decisions are not very interest sensitive. And any increased spending from borrowing at lower rates (and it’s not all that clear how much rates non-govt’s borrow at would fall) would be offset at least partly by lower income for both savers and lenders.

Scott, very interesting points. I’d like to address a few of them to both yourself and bill, however please bear in mind I’m a layman in all this and just barely educated enough in economics to discuss it so please forgive any naievete I might display.

Firstly, what about capital accumulation? Take a look at a graph of income inequality since 1900 and what you see is peaks in 1929 and 2007, with a minima in the late 60’s. From this I’d suggest that unsustainable income inequality empircally leads to a liquidty trap. Credit expansion leading up to a crash would seem to be an attempt to artificially sustain the purchasing power of the general population without adressing the root cause of the inequality. What are the root causes?

Secondly how long are the deficits sustainable for? Is there an implicit assumption in the chartalist mode of thinking that eventually the private sector is returned to health allowing a subsequent public deficit reduction? Also can you comment on the degree to which whether the funding source of the deficit is domestic or foreign matters?

Thirdly it seems to me deleveraging would be greatly accelrated under negative rates, whilst simultaneously providing considerably greater leeway for fiscal means to pick up the slack. I don’t believe that the vast majority of low and middle income households will be penalised by negative nominal rates since any tax on their savings is greatly outweighed by the reduction in their lifetime mortgage payments. Negative rates penalise two sectors – firstly the high net worth individuals with money sloshing around in hedge funds, and secondly retirees looking to live on their lifetime savings. The latter issue is of course a big problem given the demographics, but IMO we shall have to face this in any case since trying to save for retirement at 0% or even 3% is not really much more tenable than at -1%.

There is always a story of a grandparent putting $100 into a bank account for their grandchildren’s future and after so many years the bank sends the kid a bill saying they owe the bank money because they now have a negative balance.

Dear JKH

RE is the antithesis of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) because it assumes the national government has a financial budget constraint like a household and so all deficits have to be paid back sometime $-for-$. Households apparently know what because it also assumes rational expectations (so RE squared) and they react immediately stifling the expansion. It ignores the fact that households cannot create or destroy the net financial assets that the government has destroyed or created. Only the government can do that.

The underlying assumptions that have to hold to get the RE result (in their own framework) are that: (a) there is a perfect capital market – so anybody can borrow or save as much as they desire at a fixed rate which is the same for all persons – independent of whether you consider MMT to be sensible – this assumption applies to no world I know off; (b) Consumers know exactly the temporal pattern of government spending for their lifetimes – now! This is the RATEX assumption. Plainly doesn’t hold anywhere I am aware off; and (c) The current generation (us) care about all future generations equally even those that go beyond our families – children’s children’s children’s children and as far as you want to go. I think we care about our children and their children but have trouble conceiving (excuse the pun) beyond that.

best wishes

bill

Dear scepticus

First, you might like to read my blog – The origins of the crisis where I discuss the distributional issues you raise.

Second. deficits are infinitely sustainable. Private sector spending could shrink dramatically and our saving desire sky-rocket which would require expanding deficits and still there would be no problem. The normal situation, however, is that private saving is a relatively stable aggregate (except in recent years) and the automatic stabilisers adjust the deficit accordingly. There is not “funding source” for a deficit in a fiat monetary system even though governments, infused with neo-liberal logic, pretend and act as though there is. In general, it is madness for a sovereign government to borrow from foreigners. Then there is a risk of insolvency. Borrowing domestically never creates a situation of insolvency.

The only issue that a continuous deficit has to contend with is pushing nominal spending growth too quickly in relation to the real capacity of the economy to absorb it. That is, it has to dance around the inflation constraint if it wants to push the economy to full employment.

Third, remember that the only negative nominal rates we have seen are in Sweden and they are the deposit rates (the rate the central bank pays the banks for excess overnight reserves).

best wishes

bill

Hi Scepticus

Bill’s answered mostly as I would (I say “mostly” since he’s clearer and more concise than I would be), but I thought I’d clarify one point he made so there is no misunderstanding.

His point that “it’s madness to borrow from foreigners” refers to borrowing in a currency other than the one the currency-issuing government creates when it spends. If you issue the debt in your own currency, then it doesn’t matter who buys the debt, since you can never be insolvent regardless who owns it and the interest on the debt is a policy variable.

Best,

Scott

Well, vast borrowing from the domestic sector was the approach taken by japan, so it’ll be interesting to see where that goes from here – japan is in many ways a neo-chartalist pioneer it seems.

I’m inclined to agree with your assertion that while private sector saving or de-leveraging is in a strong uptrend that it makes perfect sense for the public deficit to expand, with the one caveat that this is only workable if the public sector expands to a greater percentage of GDP, in proportions roughly equal to the amount of debt transferred from the private sector.

This public sector expansion and spending cannot be spent on tax cuts, because that will just come back as private sector saving will it not, like a kind of circle jerk? The public spending financed by the deficit must be spent on infrastructure and so forth.

Taking this line of thought to its extreme conclusion (which is warrented since you suggest that public deficits are effectively unlimited), the public sector would end up eating up the private sector entirely. Presumably you have an answer as to whether there is an equilibrium point implied somewhere along the line?

Thanks also bill, for your links to the origins of the crisis article. Makes sense and echos my own view, except I’d just add that the slowing of world population growth and the subsiding boomer wave has had a lot more to do with the current problems than most peolpe think.

Hi Bill

Could I trouble you to explain to me if there is any relationship at all between the 90 day bank bill rate and the target for the cash rate. They seem to follow each other very closely.

Were they also related to the 11 am call rate in their day?

Sorry to trouble you, it sounds like it was a big day.

regards, Lefty