Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern…

The Weekend Quiz – May 29-30, 2021 – answers and discussion

Here are the answers with discussion for this Weekend’s Quiz. The information provided should help you work out why you missed a question or three! If you haven’t already done the Quiz from yesterday then have a go at it before you read the answers. I hope this helps you develop an understanding of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its application to macroeconomic thinking. Comments as usual welcome, especially if I have made an error.

Question 1:

Mainstream economists use the notion of ‘crowding out’ to argue that public spending squeezes out private spending and results in a less efficient allocation of resources overall. Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) denies that crowding out can occur.

The answer is False.

The normal presentation of the crowding out hypothesis which is a central plank in the mainstream economics attack on government fiscal intervention is more accurately called ‘financial crowding out’.

At the heart of this conception is the theory of loanable funds, which is a aggregate construction of the way financial markets are meant to work in mainstream macroeconomic thinking.

The original conception was designed to explain how aggregate demand could never fall short of aggregate supply because interest rate adjustments would always bring investment and saving into equality.

In Mankiw, which is representative, we are taken back in time, to the theories that were prevalent before being destroyed by the intellectual advances provided in Keynes’ General Theory.

Mankiw assumes that it is reasonable to represent the financial system as the ‘market for loanable funds’ where ‘all savers go to this market to deposit their savings, and all borrowers go to this market to get their loans. In this market, there is one interest rate, which is both the return to saving and the cost of borrowing.’

This is back in the pre-Keynesian world of the loanable funds doctrine (first developed by Wicksell).

This doctrine was a central part of the so-called classical model where perfectly flexible prices delivered self-adjusting, market-clearing aggregate markets at all times.

If consumption fell, then saving would rise and this would not lead to an oversupply of goods because investment (capital goods production) would rise in proportion with saving.

So while the composition of output might change (workers would be shifted between the consumption goods sector to the capital goods sector), a full employment equilibrium was always maintained as long as price flexibility was not impeded.

The interest rate became the vehicle to mediate saving and investment to ensure that there was never any gluts.

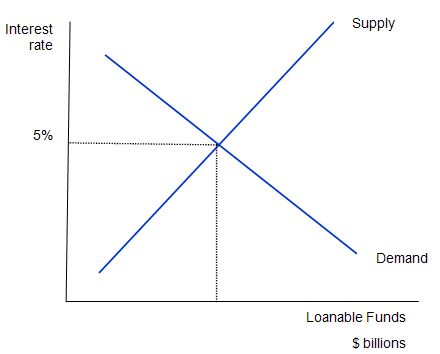

The following diagram shows the market for loanable funds.

The current real interest rate that balances supply (saving) and demand (investment) is 5 per cent (the equilibrium rate).

The supply of funds comes from those people who have some extra income they want to save and lend out. The demand for funds comes from households and firms who wish to borrow to invest (houses, factories, equipment etc).

The interest rate is the price of the loan and the return on savings and thus the supply and demand curves (lines) take the shape they do.

Note that the entire analysis is in real terms with the real interest rate equal to the nominal rate minus the inflation rate.

This is because inflation ‘erodes the value of money’ which has different consequences for savers and investors.

Mankiw claims that this ‘market works much like other markets in the economy’ and thus argues that (p. 551):

The adjustment of the interest rate to the equilibrium occurs for the usual reasons. If the interest rate were lower than the equilibrium level, the quantity of loanable funds supplied would be less than the quantity of loanable funds demanded. The resulting shortage … would encourage lenders to raise the interest rate they charge.

The converse then follows if the interest rate is above the equilibrium.

Mankiw also says that the ‘supply of loanable funds comes from national saving including both private saving and public saving.’

Think about that for a moment.

Clearly private saving is stockpiled in financial assets somewhere in the system – maybe it remains in bank deposits maybe not. But it can be drawn down at some future point for consumption purposes.

Mankiw thinks that fiscal surpluses are akin to this.

They are not even remotely like private saving.

They actually destroy liquidity in the non-government sector (by destroying net financial assets held by that sector). They squeeze the capacity of the non-government sector to spend and save.

If there are no other behavioural changes in the economy to accompany the pursuit of fiscal surpluses, then as we will explain soon, income adjustments (as aggregate demand falls) wipe out non-government saving.

So this conception of a loanable funds market bears no relation to ‘any other market in the economy’ despite the myths that Mankiw uses to brainwash the students who use the book and sit in the lectures.

Also reflect on the way the banking system operates – read Money multiplier and other myths if you are unsure. The idea that banks sit there waiting for savers and then once they have their savings as deposits they then lend to investors is not even remotely like the way the banking system works.

This framework is then used to analyse fiscal policy impacts and the alleged negative consequences of fiscal deficits – the so-called financial crowding out – is derived.

Mankiw says:

One of the most pressing policy issues … has been the government budget deficit … In recent years, the U.S. federal government has run large budget deficits, resulting in a rapidly growing government debt. As a result, much public debate has centred on the effect of these deficits both on the allocation of the economy’s scarce resources and on long-term economic growth.

So what would happen if there is a fiscal deficit. Mankiw asks: ‘which curve shifts when the fiscal deficit rises?’

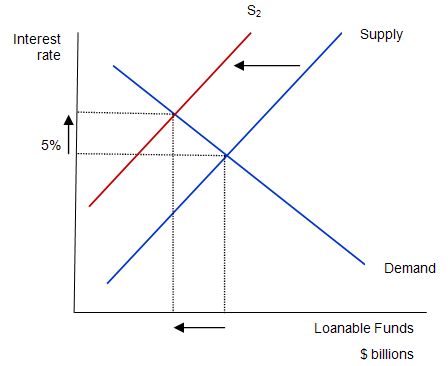

Consider the next diagram, which is used to answer this question. The mainstream paradigm argue that the supply curve shifts to S2. Why does that happen?

The twisted logic is as follows: national saving is the source of loanable funds and is composed (allegedly) of the sum of private and public saving. A rising fiscal deficit reduces public saving and available national saving.

The fiscal deficit doesn’t influence the demand for funds (allegedly) so that line remains unchanged.

The claimed impacts are: (a) ‘A budget deficit decreases the supply of loanable funds’; (b) ‘… which raises the interest rate’; (c) ‘… and reduces the equilibrium quantity of loanable funds’.

Mankiw says that:

The fall in investment because of the government borrowing is called crowding out … That is, when the government borrows to finance its budget deficit, it crowds out private borrowers who are trying to finance investment. Thus, the most basic lesson about budget deficits … When the government reduces national saving by running a budget deficit, the interest rate rises, and investment falls. Because investment is important for long-run economic growth, government budget deficits reduce the economy’s growth rate.

The analysis relies on layers of myths which have permeated the public space to become almost ‘self-evident truths’. Sometimes, this makes is hard to know where to start in debunking it.

Obviously, national governments are not revenue-constrained so their borrowing is for other reasons – we have discussed this at length.

I discussed that issue in the introductory suite of blog posts:

1. Deficit spending 101 – Part 1 (February 21, 2009).

2. Deficit spending 101 – Part 2 (February 23, 2009)

3. Deficit spending 101 – Part 3 (March 2, 2009).

But governments do borrow – for stupid ideological reasons and to facilitate central bank operations – so doesn’t this increase the claim on saving and reduce the ‘loanable funds’ available for investors? Does the competition for saving push up the interest rates?

The answer to both questions is no!

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) does not claim that central bank interest rate hikes are not possible.

There is also the possibility that rising interest rates reduce aggregate demand via the balance between expectations of future returns on investments and the cost of implementing the projects being changed by the rising interest rates.

MMT proposes that the demand impact of interest rate rises are unclear and may not even be negative depending on rather complex distributional factors. Remember that rising interest rates represent both a cost and a benefit depending on which side of the equation you are on. Interest rate changes also influence aggregate demand – if at all – in an indirect fashion whereas government spending injects spending immediately into the economy.

But having said that, the Classical claims about crowding out are not based on these mechanisms.

In fact, they assume that savings are finite and the government spending is financially constrained which means it has to seek ‘funding’ in order to progress their fiscal plans.

The result competition for the ‘finite’ saving pool drives interest rates up and damages private spending. This is what is taught under the heading ‘financial crowding out’.

A related theory which is taught under the banner of IS-LM theory (in macroeconomic textbooks) assumes that the central bank can exogenously set the money supply.

Then the rising income from the deficit spending pushes up money demand and this squeezes interest rates up to clear the money market.

This is the Bastard Keynesian approach to financial crowding out.

Neither theory is remotely correct and is not related to the fact that central banks push up interest rates up because they believe they should be fighting inflation and interest rate rises stifle aggregate demand.

However, other forms of crowding out are possible.

In particular, MMT recognises the need to avoid or manage real crowding out which arises from there being insufficient real resources being available to satisfy all the nominal demands for such resources at any point in time.

In these situation, the competing demands will drive inflation pressures and ultimately demand contraction is required to resolve the conflict and to bring the nominal demand growth into line with the growth in real output capacity.

Further, while there is mounting hysteria about the problems the changing demographics will introduce to government fiscal balances, all the arguments presented are based upon spurious financial reasoning – that the government will not be able to afford to fund health programs (for example) and that taxes will have to rise to punitive levels to make provision possible but in doing so growth will be damaged.

However, MMT dismisses these ‘financial’ arguments and instead emphasises the possibility of real problems – a lack of productivity growth; a lack of goods and services; environment impingements; etc.

Then the argument can be seen quite differently.

The responses the mainstream are proposing (and introducing in some nations) which emphasise fiscal surpluses (as demonstrations of fiscal discipline) are shown by MMT to actually undermine the real capacity of the economy to address the actual future issues surrounding rising dependency ratios.

So by cutting funding to education now or leaving people unemployed or underemployed now, governments reduce the future income generating potential and the likely provision of required goods and services in the future.

The idea of real crowding out also invokes and emphasis on political issues.

If there is full capacity utilisation and the government wants to increase its share of full employment output then it has to crowd the private sector out in real terms to accomplish that.

It can achieve this aim via tax policy (as an example). But ultimately this trade-off would be a political choice – rather than financial.

Question 2:

A rising government deficit will always allow the private domestic sector to increase its overall saving in nominal terms.

The answer is False.

If the external balance is zero (that is, net exports equal zero) then there is a one-to-one correspondence between the government balance and the private domestic sector balance such that, for example, a 2 per cent fiscal deficit must be associated with a 2 per cent private domestic sector balance surplus.

So in this circumstance the answer would be true.

But things get complicated when we introduce positive or negative external balances. Then a 2 per cent fiscal deficit might be associated with a 3 per cent external deficit and so the private domestic sector balance will be in deficit overall (spending greater than income).

Saving might still be positive but overwhelmed by spending which means that overall the sector is in deficit.

So the answer is only true if the fiscal deficit is larger (as a percent of GDP) than the external balance and growing faster.

Question 3:

Assume the government increases spending by $100 billion in the each of the next three years from now. Economists estimate the spending multiplier to be 1.5 and the impact is immediate and exhausted in each year. They also estimate the tax multiplier (which captures the impact of rising tax rates on GDP) to be equal to 1 and the current average tax rate is equal to 30 per cent. What is the cumulative impact of this fiscal expansion on GDP after three years?

(a) $135 billion

(b) $150 billion

(c) $315 billion

(d) $450 billion

The answer was $450 billion.

In Year 1, government spending rises by $100 billion, which leads to a total increase in GDP of $150 billion via the spending multiplier. The multiplier process is explained in the following way.

Government spending, say, on some equipment or construction, leads to firms in those areas responding by increasing real output.

In doing so they pay out extra wages and other payments which then provide the workers (consumers) with extra disposable income (once taxes are paid).

Higher consumption is thus induced by the initial injection of government spending.

Some of the higher income is saved and some is lost to the local economy via import spending.

So when the workers spend their higher wages (which for some might be the difference between no wage as an unemployed person and a positive wage), broadly throughout the economy, this stimulates further induced spending and so on, with each successive round of spending being smaller than the last because of the leakages to taxation, saving and imports.

Eventually, the process exhausts and the total rise in GDP is the ‘multiplied’ effect of the initial government injection.

In this question we adopt the simplifying (and unrealistic) assumption that all induced effects are exhausted within the same year. In reality, multiplier effects of a given injection usually are estimated to go beyond 4 quarters.

So this process goes on for 3 years so the $300 billion cumulative injection leads to a cumulative increase in GDP of $450 billion.

It is true that total tax revenue rises by $135 billion but this is just an automatic stabiliser effect. There was no change in the tax structure (that is, tax rates) posited in the question.

That means that the tax multiplier, whatever value it might have been, is irrelevant to this example.

Some might have decided to subtract the $135 billion from the $450 billion to get answer (c) on the presumption that there was a tax effect. But the automatic stabiliser effect of the tax system is already built into the expenditure multiplier.

Some might have just computed $135 billion and said (a). Clearly, not correct.

Some might have thought it was a total injection of $100 billion and multiplied that by 1.5 to get answer (b). Clearly, not correct.

You may wish to read the following blog posts for more information:

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2021 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

There is another version of the loanable funds theory and the crowding-out effect in private investment as a result of higher real interest rates stemming from government deficits. This model assumes that the public sector does not save, so the equilibrium interest rate is determined by the demand for and supply of funds in the private sector alone. Then, the borrowing needs of government to finance its deficit will shift the demand curve to the right, raising the equilibrium interest rate and inducing private savers to increase saving by moving up along the fixed supply curve. However, at the new and higher interest rate the quantity demanded for loanable funds will decrease and private investment will decline, thus the crowding-out. The difference in this model is that the equilibrium quantity of loanable funds expands instead of contracting, as in Mankiw’s model. To me this version seems more “reasonable” given that the government very rarely saves by running surpluses.

Just wondering about the second part of the post about MMT and power and when you might write that. Been anticipating it now for a couple of weeks and hope it becomes ready soon.

If you need any ideas about it, I will offer some of mine- MMT mostly concerns itself with the powers of the currency issuing government which are far larger than conventional economics realizes.

The MMT Job Guarantee would change the power relationships between lower paid workers and the rest of society- not just their current employers. In a good way as far as I am concerned.

And then you can contrast the conventional view that people must serve the economy with the MMT view that the economy is there to serve the people. And that has something to do with power maybe.

Well anyways, those are a few of my thoughts and I am anticipating your continuation of MMT and Power regardless.

Demetrios Gizelis, doesn’t your version depend on some sort of fixed supply of ‘funds’, when the actual constraints are always the limitations of real resources that are available?

Jerry, this isn’t my version. It’s another mainstream exposition of the crowding-out effect that asserts private investment is chocked off when the government expenditure is debt financed via a different route. More specifically, the increase in equilibrium real interest rate is the result of an increase in demand for loanable funds with their supply curve staying put, whereas in Mankiw’s model there is a decrease in supply of loanable funds while the demand curve stays the same.

However, we know that both explanations are wrong form MMT perspective because a sovereign currency issuing government faces only real resources constraints but not financial constraints.

My mistake Demetrios. Sorry- I should have realized you were not advocating that version. I might be getting hyper-sensitive to anything based on loanable funds type thinking. It is amazing to me that I accepted ‘loanable funds’ hypotheses as true when it was originally taught as part of economic theory. And now I see it as complete garbage. Well, I guess we can live and learn with a little luck.

3/3 – I’m pretty much an economist now!

Jerry, the tragedy is that the LF theory, in one version or another, is still taught in the majority of universities throughout the world to explain real interest rate determination within the context of pure intermediation banking system and the exogeneity of money creation. However, MMTers posit that money is endogenously created with government expenditure and the latter doesn’t depend on the generosity of bond vigilantes. Also, Richard Werner has empirically tested the validity of the three contesting theories of money creation and proved that only the credit creation theory successfully passed the test, while the fractional reserve, and intermediation theories of bank money creation failed.

Off topic question: a government could choose not to issue bonds and not pay interest on excessive reserves, just removing excesse liquidity with taxes?

Rafael, traditional monetary policy is conducted by a CB using three tools: open market operations, required reserve ratio (rrr), and discount rate. Non existence of bonds and absence of interest on reserves would drive the overnight interbank rate to zero, which is what Warren Mosley has coined the natural rate of interest. The CB still can manipulate liquidity by changing the rrr and/or the discount rate. At the extreme it could go back to 100% reserve banking, as some economists have advocated. There are other options as well, i.e. credit guidance, increase in capital adequacy ratio, etc. However, taxes are the domain of government and from MMT perspective are used to influence aggregate demand, incentivize consumption, and channel investment as well and only indirectly impact on liquidity.

I hope this is of some help!

Demetrios,

Can you explain why a substantial proportion (50% +) of bank liabilities are deposits?

Why do banks take deposits?

What do they do with the funds?

If credit is created ex nihilo why do the banks need to take deposits?

Why do they have substantial short term and long term debt?

Dear Henry, thank you for addressing to me these questions and I do hope that they are well intended. Allow me to start by making clear that any discussion about banking ought to begin with what is money and how we measure it. Traditionally, money is defined as anything being accepted as a medium of exchange, and it performs three functions: a) medium of exchange, b) unit of account, and c) store of value. Another function, that is “standard of deferred payment” has been placed in oblivion, although it’s of utmost importance because it is money that we use to settle debts. When it comes to money supply, it can be measured in a variety of ways, narrowly or broadly. In the USA the Fed measures it in three different ways: M0 consists of currency in the hands of the public and banks’ reserve balances, and this is the most narrow definition. M0 is the monetary base of the economy and it is also known as high power money, due to the ability of expanding through the multiplier process, according to the fractional reserve money creation theory. M1 is M0 plus demand deposits at depository institutions, and traveler’s checks. In this connection M1 plays the function of medium of exchange. M2 is M1 plus savings deposits, money market mutual funds, certificate of deposits, and other time deposits. All the additional items included in M2 are called near money because although they can’t be used directly for transaction purposes, they are very liquid and easily transformed into cash. M3 is not longer reported by the Fed. As of March 2021, in the U.S. the monetary base was $5.25 trillion, M1 $6.75 trillion, and M2 $19.4 trillion.

Of the total money supply in the U.S., and most other advanced economies, only three percent is created by the Fed whereas ninety seven percent is bank money, mainly created in the loan making process.

Commercial banks are profit seeking institutions that try to compromise three objectives: profitability, liquidity, and solvency. Profits are generated by the interest rate spread and various fees on services, liquidity is secured from reserves, and solvency is provided by capital (tier 1 and 2, see below). The liabilities of a typical bank consist of deposits, and borrowed funds while the assets are composed of vault cash and reserves, loans, securities, and fixed assets. The difference between total assets and total liabilities is net worth or owner’s equity. The exact amount of this capital is regulated by the Basel Accords (Basel I, II, and III) and it’s calculated as a risk weighted average of assets. Bank capital is divided into Tier 1 and Tier 2. The former is equity share capital and the latter includes, among other things, subordinated term debt, and hybrid capital instruments. Banks issue debt in order to satisfy the Basel capital adequacy requirements and thus remain solvent. However, this did not insulate a number of banks from becoming insolvent during the 2007-8 financial meltdown. They accept deposits in order to remain liquid because of the time miss match between assets and liabilities maturities. Generally speaking, banks borrow on short term basis and lend on long term. The intermediation theory of money creation and the fractional reserve theory argue that loans come from deposits. The former argues that banks operate as simple go-in-between lenders and borrowers and only shuffle around liquidity without been able to create money either individually or in the aggregate. On the other hand, the later asserts that banks individually lend excess reserves and affect the money supply in the aggregate inversely with the required reserve ratio. That is, the simple deposit multiplier is the reciprocal of required reserve ratio. The third approach to money creation is the credit theory, which advocates that lending and money creation doesn’t originate either from deposits or from excess reserves but it is created ex nihilo, or from thin air, and it is the only one that has been empirically verified in a 2014 paper by Richard Werner with the title “Can Banks Individually Create Money out of Nothing?”

I hope that I answered all your questions and I do apologize for being lengthy.

Demetrios,

Thank you for your fulsome reply. However, I am not satisfied it has answered my questions nor has it persuaded me to change the way I view the situation.

I have read the \Werner paper. It addresses only a part of the process involved in banking. He completely fails to address the payments side of the banking business. When a bank generates a loan it eventually creates on obligation on itself. It has to settle payments arising from claims by other banks owing to the disbursement of loan funds. It can finance these claims from its cash resources, borrowing from the interbank market or borrowing from the central bank. Clearly this is not sustainable. Banks take deposits because they provide a cheaper source of funds which enables them to finance their net obligations to the banking system.

Banks cannot create loans ex nihilo. Banks must also take deposits.

Banks could also issue loans to all and sundry if they could create credit ex nihilo. Clearly this is not the case. Banks have to establish the solvency of their borrower clients.

Any cursory look at the accounts of pure banking businesses will show that deposits taken and debt raised more or less match loans on issue.

Dear Henry,

You asked me a set of questions and I provided specific lengthy answers based on my 25 years of bank experience at top managerial level. My intention is not to persuade you, and you have every privilege to stick to your own views. However, I know first hands that the credit division of a bank doesn’t consult any other division, internally or externally, in approving and extending a loan. It only evaluates the credit worthiness of the applicant and decides strictly on the likelihood that the payments will be met when are due. This is reality and everything else is fiction. The overwhelming majority of deposits are created in making loans (this is what termed bank money) and do not reflect ordinary savers’ deposits. It is simply double book keeping entries where the new loan is recorded on the assets side, being a bank’s claim on the borrower, and also as a liability because it’s an obligation to the same agent. Nevertheless, banks need savers’ deposits in order to settle interbank accounts with the the CB operating as the clearing house and to load up ATM machines. On any day the inflows and outflows of a typical bank are netting out to approximately zero, and only very seldom there is cash drainage. The fact that banks do not rely on customers’ deposits to create loans is well known to any knowledgeable central banker and this has been publicly admitted by the Bank of England and the Bundesbank as well.

In closing, let me iterative that it’s your absolute right to stick to your views that banks act as simple intermediaries in a modern economy and therefore it is scientifically correct the assertion of money neutrality and because of that neoclassical macroeconomic models exclude the banking sector. And Queen Elizabeth’s question “didn’t you see it coming” about the GFC will remain unanswered.

Henry,

For me, if I remember correctly, this was cleared up by Cameron Murray, in a blog post where he introduced his book _Game of Mates_. What I recall from there:

– banks do create loans ex nihilo. (As pointed out by Alan Holmes in his conference paper of 1969.)

– a bank’s assets (typically reserves) are drawn down when it funds its borrowers’ spending.

– a bank does hope for an incoming flow of deposits to counter the outgoing flow of borrowers’ spending.

Luckily, these flowing deposits aren’t scarce, because other banks are also creating loans ex nihilo. Just as this bank’s borrowers’ cheques wind up at other banks, and have to be funded, other banks’ borrowers’ cheques wind up at this bank, and bring in funds. As you’ve rightly said, any random imbalances can be filled in in the interbank credit market, etc. A persisting imbalance would be a problem in business strategy.

If I remember right, one of Cameron Murray’s points was that the banks need to play nice together to stay in business. A bank’s loans can’t grossly outpace it’s share of the market’s deposit flows, else corrective measures need to be taken. Hence “Game of Mates”. In the financial news, you’ll see stories of how the biggest banks are now and then forming consortia to take on mammoth projects. That would be corrective measures in advance.

Demetrios,

In some ways we are saying the same thing, however there are a couple of things where we disagree.

I accept that the loan generating process does not directly involve the consideration of how the loan will be financed by the bank. However, the business planners in the bank have to give due consideration to how to finance the claims on the bank that inevitably will arise from the banking system as a result of the loan being raised and eventually the funds being used by the borrower.

You say:

“The overwhelming majority of deposits are created in making loans (this is what termed bank money) and do not reflect ordinary savers’ deposits.”

I am concerned by this statement because it does not make sense. A loan is normally sought by the borrower for a specific purpose. The borrower is going to draw down the funds as soon as the bank makes them available. So the borrowers deposit account will soon have a zero credit. So I can’t see how your statement can be true. I would like to see some evidence backing your statement up.

“Nevertheless, banks need savers’ deposits in order to settle interbank accounts with the the CB operating as the clearing house and to load up ATM machines. ”

Exactly the point I made in my previous comment. The bank needs to fund the claims on itself that arise from the loan funds being drawn down and spent. So I would say that while deposits might not fund loans, deposits do fund the claims on the bank that arise from issuing the loans. So the banks planners have to have an eye on this. They know that in the course of their normal banking business they will take deposits and that these deposits will fund the claims which arise back from the banking system. They could finance these claims, as I mentioned in my original comment to you, via their cash reserves or borrowing interbank or from the central bank. They will do this from time to time depending on their payment flows but they know that these debts can be replaced by deposit taking in the normal course of business, deposits being preferable because they are cheaper.

As I said in my previous comment, if banks did create credit ex nihilo there would be no need for them to take deposits. The bank ultimately has to have an eye on how it finances the claims on itself that arise because of its lending.

Again I reiterate, I am not saying banks fund loans with deposits but they do have to fund the claims on themselves coming back from the system as a result of their lending. It is too simplistic to say banks create credit ex nihilo.

Demetrios,

There is one other matter.

You did not comment on the fact that, by and large, the deposits and debts in bank’s liabilities numerically match their loan books.

And, by the way, you do not have to persuade me of anything. I am interested to read your responses to my questions and the points I make.

Henry, perhaps you would be interested in Eric Tymoigne’s posts about banking. It is a lot of reading but I think it would answer your questions. I think you ask too much of commenters on a blog to explain the banking system to you. The answers already provided by Demetrios were more than anyone could expect given the limitations of time and of a comment section. These are not simple questions that can be answered in fifty or sixty words in a comment.

Do the reading if you are interested. It is an excellent series that I believe is compatible with the general MMT views on banking.

http://neweconomicperspectives.org/money-banking

Mel,

Thanks for that.

It all sounds reasonable except for the ex nihilo part.

I think it is a stretch to be so categorical.

Jerry,

I’ve have a pile of Tymoigne’s stuff (the material you referred to) sitting on one of my shelves waiting to be read. I scooted thru his Part 10.

I seem to be saying what he said but he said it with a good deal more elaboration.

I’m sticking to what I said above: “I am not saying banks fund loans with deposits but they do have to fund the claims on themselves coming back from the system as a result of their lending. It is too simplistic to say banks create credit ex nihilo.”

And the cheapest way to do this over time is to take deposits.

And contrary to what Demetrios asserts above, it does not make sense that the majority of deposits held by a bank are those generated in the loan making process.

“So the borrowers deposit account will soon have a zero credit.”

And the credit goes to the recipient’s account. What is the overall change?

Alright Henry. I think you are wrong. I personally can create credit out of nothing except my promise to pay- and banks have far more credibility than I do about that promise to pay part. “Ex nihilo” if you want to use Latin for some reason.

Sure those bank promises need to be funded at the time they are demanded to be. And if it comes down to that- deposits banks accept are generally a cheap way of funding. But the loans are “ex nihilo” at inception. And as Demetrios and Mel explained, credits from other banks are usually coming in while the liabilities to other banks are due, and there is not necessarily so much need for the deposits of actual ‘savers’ when the deposits that arrived from the spending of borrowers from other banks are considered. So that is how you can understand that 95%+ of what we call money is derived from bank loans that gets cycled around.

Well that is how I understand it. I would be happy for you to correct my understanding.

Allen,

“And the credit goes to the recipient’s account. What is the overall change?”

More then likely it ends up with another bank, after it has been spent, as a credit in some kind of savings or cheque account.

The deposit is there because someone put it there and not because it’s there because a bank raised a credit in a deposit account on behalf of a borrower as part of a loan generating process.

Jerry,

Ask yourself the question: “Why do banks take deposits?”

There’s another question: “Why is that, by and large, the numerical value of deposit and borrowings by a bank is the same as the bank’s loans outstanding?”

The answer to both questions that I would give, as I have from my second comment and what Tymoigne says and Demetrios and Mel have said, is that the bank has to finance the claims on itself coming back from the system as a result of making loans.

And the bank happily takes deposits because it is probably the cheapest way to finance these claims. All the bank has to worry about is that it gets its share of deposits flowing into the banking system. And occasionally it goes into the bond markets and short term money markets to borrow money.

Now if you want to say categorically, despite the above, that banks create money from nothing, so be it.

Dear Henry,

When I teach M&B students have difficulty understanding the concept of deposit multiplier within the framework of fractional reserves banking model. To them it looks like a magician pulling rabbit out of hat! So, I tell them imagine that there is a Monopoly bank with many branches in the entire country. Since your disagreement is with what happens when funds are withdrawn from the demand deposit credited with the loan, in this Monopoly bank the check payment will be deposited in another branch of the same bank. Do you still have a problem in this case; I presume you do not. Now, to make the case more realistic, in a multi-bank system the funds inflows and outflows for each individual bank approximately cancel out on the average during any business day, thus there isn’t any serious drainage of funds. Problem solved!

Regarding your observation that loans match deposits, it has to be so because it’s simply double bookkeeping accounting records. That is, a newly created loan is an entry on the assets side, being a claim of the bank against the borrower and simultaneously a liability entry as deposit, because the same agent gets a claim against the bank.

I think we have more than exhausted the topic!

Henry,

“And the bank happily takes deposits because it is probably the cheapest way to finance these claims.”

It goes beyond that. If banks stopped taking deposits, if they claimed there was a cheaper way, then the whole credit system would be destroyed. If somebody borrowed $1000 to buy a refrigerator at my appliance store, and the bank decided they didn’t need my deposit, then my business would be ruined. Maybe I could repossess the refrigerator. And when the word got around, people would realize that taking out loans was useless. Playing fair in the Game of Mates is really the foundation of the retail banking system.

Imagine a version of Warren Mosler’s Money Story where the government refuses to accept its own money to clear tax debt. End of money — probably end of government.

A feature like this is one thing that makes the U.S. health insurance system the special hell that it is. Individual insurers form networks of medical service providers, and your insurance benefits are only worth anything inside that insurer’s network. If you find yourself anywhere else, you’re on your own.

I don’t know if this analogy will work, but imagine there are two expert circus jugglers performing together. And they keep throwing rings up into the air between them. At some point you might ask where are these rings coming from- how do they keep throwing them up in the air towards each other? With jugglers it is pretty obvious they are catching the rings the other one is throwing and that allows them in turn to throw themself. But at each point in the process the juggler might just have one ring while 20 of them are up in the air (these are really good jugglers). And they have an assistant called the central bank that will almost always toss in another ring if they drop one and another assistant called the government that almost always is tossing more rings to them than it takes away. So it becomes obvious they can keep tossing the rings (if they are very skilled) even though they only have one in their hand at any time. Now imagine the rings are promises and it becomes easy to see that the juggler doesn’t really much need an actual ring in his hand to toss up a promise so long as it is accepted for a short while because the other juggler is also tossing promises which will net out between them. Now you can maybe see that the jugglers can keep an extraordinary amount of the ‘promise rings’ in the air between them and it only becomes a problem when they don’t net out.

Well, I have no idea if this analogy is at all helpful, but on the chance it might be I will post it.

Jerry,

I find the circus jugglers story very amusing although I can’t really relate it to banking operations as such. However, I’m tempted to extend it by introducing a gremlin in the audience who secretly throws a banana peel on the stage and one of jugglers steps on it, looses her balance and falls down. How many rings will remain flying in the air? Isn’t this what happened during the financial crisis of 2007-8? Although we know who that gremlin was (big profit hungry bankers) nobody ever paid anything for the damages inflicted on society, instead of getting rotten in jail.

I guess it would be a rare banker that appreciated being compared to a circus performance 🙂

When the juggler slips on the banana peel, that is when their assistants start throwing all kinds of rings up into the air in an attempt to keep the show going. And it becomes very clear that the assistants can throw any number of rings out there even though they would rather not because they want the audience to think the rings are rather rare and special even though they are not. Why they don’t replace the juggler that slips often is a mystery though.

Oh well, I may not be very good with making up stories that explain banking. Henry will have to figure this out some other way.

Demetrios,

“Now, to make the case more realistic, in a multi-bank system the funds inflows and outflows for each individual bank approximately cancel out on the average during any business day, thus there isn’t any serious drainage of funds. ”

Yes, I accept that and I have said as much.

“Regarding your observation that loans match deposits, it has to be so because it’s simply double bookkeeping accounting records. ”

Not for any one particular bank. If in-credit-deposits comprised of accounts representing the liabilities’ side of the loan making process then that would mean the bank had granted untold loans and none of the funds of which had been drawn down by the borrowers. This is absurd. When the funds are drawn down by the borrower the deposit account goes to zero credit. On any particular day only a small number of deposit accounts would be related to the loan making process. These would be accounts that have been credited with loan funds but not yet drawn down by the borrower.

Mel,

“,,,,,,and the bank decided they didn’t need my deposit, then my business would be ruined.”

A bank won’t bar you from depositing the funds coming from the sale but they might cut back their deposit rates if the deposit flow is too high.

As I said above, all banks need to do is make sure they get the appropriate share of deposits.

Jerry,

“I have no idea if this analogy is at all helpful”

It is an interesting analogy and if you actually read what I said further above and not what you think I said, you will realize I have said the same kind of thing.

Mel,

” If banks stopped taking deposits, if they claimed there was a cheaper way, then the whole credit system would be destroyed.”

Which goes to support the argument I am making.

Taking deposits is a critical part of the credit creation process.

“More then likely it ends up with another bank, after it has been spent, as a credit in some kind of savings or cheque account.”

Which is another way of saying there is no overall change to deposits.

Allan,

What is your point?

Henry, I appreciate that you did not rip my stupid story to shreds. You are a kind and intelligent person which is why I always like arguing with you 🙂 Even if you are occasionally almost as stubborn as I am. Which I kind of admire to be completely honest.

Now I admit my story has a lot of limitations- but I don’t see how it is kinda the same as you were saying. When the bankers I mean jugglers start throwing ‘promise rings’ to each other that cancel each other out (in my imagination this happens mid-air with a suitable flash and bang to amaze the audience) along with the real rings they are skillfully juggling all the time, well I am saying those ‘promise rings’ are their ability to create money ‘ex nihilo’ or whatever through loans. And they can throw way more than they could ever catch so long as they cancel out in the air. And that they cancel out means there are many multiples of them compared to the real rings.

“The bank needs to fund the claims on itself that arise from the loan funds being drawn down and spent. ”

The bit you are missing Henry is the precise mechanism by which they are drawn down and spent.

Spending is nothing more than changing the ownership tag on the deposit. They don’t actually move anywhere. They just change hands.

– When you spend within a bank then the tag is just changed on the deposit.

– When you spend with a person using another bank, the tag is changed to that bank – who then creates a matching interbank loan and a customer deposit in its own books.

– When a bank sells capital bonds or equity, the liability type just changes from deposit to bond/equity.

– When a bank pays back bonds or equity, it changes the liability type from bond/equity to deposit.

– Should banks end up with interbank loans with each other, they are netted off to keep the books clean.

Central banking and even cash are just optimisations on this accounting process. And it is the trip via the central bank process that causes interest rate adjustments to bind.

Balance sheets always have to balance.

Neil,

“Balance sheets always have to balance.”

I agree with most of what you say, but I don’t see your point.

As far as I can see, loans are advanced then they eventually have to be financed by the bank that made them.

I think the “ex nihilo” is a stretch and misleading.

Look at annual reports and other documents of banks. The one’s I have seen speak of retail (deposits) and wholesale (bond issues) funding of their business. Nothing to the effect that “we pulled $20B in money from the thin air this financial year”.

That doesn’t mean I necessarily subscribe to other theories of money creation.

“As far as I can see, loans are advanced then they eventually have to be financed by the bank that made them.”

They are financed automatically when the loan and the deposit is created.

The trick then is to hold onto that financing as other institutions try to obtain that customer for marketing purposes – which is the real reason banks like depositors. The data from their transaction record are useful for selling secondary products like insurance.

If I can nick a depositor from your bank then I can pay them, say, 0.5% while charging you 0.6%. Inserting myself as middleman is free margin to me you can’t avoid paying other than by trying to nick the depositor back. That hustle continues forcing the interbank margin down to next to nothing. But wholesale deposit rates will always be slightly more expensive and much more volatile as a net cost than retail deposits.

Neil,

“They are financed automatically when the loan and the deposit is created. ”

How?

Loans create deposits.

The collateral is charged creating a financial derivative asset which sits on the balance sheet of the bank. That creates a balancing liability to the borrower selling the charge to the bank, who can then instruct the bank to transfer that liability to somebody else internally within the bank.

It’s a balance sheet expansion.

What I think Henry might have failed to appreciate is that (to use a helpful phrase I learnt from Neil) “Money does not stop at first use”.

So, apart from any taxation that is imposed on transactions in the spending chain, the initial loan amount cannot be destroyed, even after it has passed through several hands. It will always remain in the banking system, at one bank or another, until it is gradually eroded (until extinguished) either by taxation, or by the sudden, or gradual, repayment of the loan by the initial borrower.

The whole affair needs to to be seen in aggregate, and, in aggregate, it’s not actually *possible* to “remove” money from the banking system – apart from via taxation, loan repayment, and I presume govt bond purchases(?) – so whatever’s left of the initial loan amount *must* still sit in a deposit account, somewhere in the banking system.

That way – in aggregate – it all balances out. Individual banks may still need to lend to and borrow from each other, or the CB, to balance their books on a nightly basis, but, *in aggregate*, the whole system does balance.

Mr. S.,

I do get all that.

What I don’t get at all is Neil’s explanation. 🙂

@ Henry, if you do “get all that”, then how can you possibly think that *banks require deposits in order to create loans*?

Sure, the balance sheet needs to… er, balance, at the end of each day – but if by some quirk of fate, all the loans made by Bank A this week happen to be paid over (in transactions for which the loans were authorised) to Banks B, C, & D, who, by some equally unusual quirk, themselves made no loans this week – then yes, Bank A will be short on the liability side, but will then borrow reserves either from, now reserve-bloated, Banks B, C and D , or the Central Bank, if B, C and D think that A is in uncreditworthy.

Like Neil – and everyone else these days – says: Loans *create* deposits.

How could it be otherwise – unless banks issued loans directly in cash, and the borrower’s seller kept the proceeds of the sale under their bed?

Let me do it in terms of something we should all understand – a mortgage.

A mortgage isn’t a loan. A mortgage is a financial derivative asset that represents a part ownership of a property. It is the right to veto the sale of a property and the right, under certain conditions, to sell the property.

Banks buy mortgages from people with properties, and they buy them by issuing their own stock in exchange. They then set up a scheme where you can buy that mortgage back over time by returning equivalent stock to that bank. When you have returned enough the mortgage is returned to you and deleted.

The stock of a bank are like shares and the ownership of them can be transferred between people.

Banks aren’t that complicated. They work just like any other corporate structure. They fund themselves by obtaining assets from people and issuing some form of stock for them in exchange.

Mr. Shigemitsu,

“….then how can you possibly think that *banks require deposits in order to create loans*?”

I don’t believe I have actually said that.

What I have said is that the bank has to finance the claims that come back from the system once the loans monies are spent.

So the bank uses its cash reserves, it borrows or it takes deposits.

OK, I think I might see what you are getting at:

To do so, we need to imagine a situation where poor old Bank A makes a whole lot of loans that month, to borrowers who purchase goods, services, whatever… from sellers who just so happen to only bank with Banks B, C & D.

Reserves from Bank A’s central bank A/c will be transfered by the central bank to Banks B, C & D’s reserve accounts accordingly.

That month, Banks B, C & D also multiple issue loans, as usual, to their borrowers, who spend that money on goods, services etc, with sellers, BUT…….it just so happens that none of them, by some ghastly quirk of fate, bank with Bank A !!!!

So Bank A has made all those loans, transferred millions in reserves to B, C & D… but have received no deposits resulting from B, C, & D’s loans, because they have all been lent, spent and deposited between themselves.

Yes, in that situation, Bank A may be short on reserves, and may then need to borrow from Banks B, C & D – who will have an excess of reserves, from all of Bank A’s spent loans being deposited with them – or from the Central Bank.

Is this what you were trying to explain?

And, if so – does this unrealistically one-sided and unbalanced situation ever actually happen?

Mr. S.,

“Is this what you were trying to explain?”

In part yes. But as you outline, the unrealistic case results in Bank A having to fund its obligations by debt or one kind or another.

In reality, Bank A will receive it share of deposits. It is these that will finance the obligations it has to the system as a result of making loans and the loan monies being spent.

Bank A’s debt liabilities are replaced by deposits.

When government spends, it creates reserves in the system (vertical money) all else is about moving that reserves around within the system: among the private and the foreign sectors, as the sectoral balances equation explained (until tax is made).

Household debts (loans) can drive GDP but it does not add any new net reserves position into the system (otherwise, the private sector can create money like bitcoin).

Thus, deposited money, when making loan, is created out of thin air (well, in a way, it is not, as this is a liability or credit against an asset or contract).

How the issuing bank manages its liquidity (credit money) is entirely a separate matter. It has nothing to do with taking money from other depositors, which are parked in an account at the central bank in an entire sum along with others.’ deposits).

No bank cannot do that directly, as the balance sheet of central bank does not allow for this transaction to occur.

(Sorry, I couldn’t help joining in the fun with you all talking about this issue)!

“What I have said is that the bank has to finance the claims that come back from the system once the loans monies are spent.

So the bank uses its cash reserves, it borrows or it takes deposits.”

That financing happens automatically, otherwise the loan monies can’t be spent as a matter of accounting.

Spending is nothing more than transfer of ownership of the loan monies *within the bank that issued them*. They don’t go anywhere else.

Neil,

“That financing happens automatically, otherwise the loan monies can’t be spent as a matter of accounting. ”

If that’s your definition of financing, that’s fine. It’s not mine.

Once the loan is granted the lending bank creates a deposit account for the borrower and credits it with the loan amount. No financing involved.

Once the loan monies are spent and the consequential obligations on the lending bank as a result of the spending of the loan monies arise then the lending bank has to make payment to the claimant bank in settlement of the claim.

That’s when the financing begins.

“Once the loan is granted the lending bank creates a deposit account for the borrower and credits it with the loan amount. No financing involved.”

It doesn’t get credited until drawdown in a bank. The drawdown and transfer are generally coincident, and I can assure you that the treasury department has costed in the cost of the new liability to the bank.

That’s because it takes weeks to get a loan approved, and treasury has the closure projections. They know what is going where and who will likely end up owning the deposit created. Their job after all is to maintain the margin.

The obligation *is* the deposit created, and treasury will try and ensure that liability is held by the most cost-effective holder possible at settlement whatever gets setup at clearing. Preferably a depositor in the bank to cut out the interbank middleman.

“then the lending bank has to make payment to the claimant bank in settlement of the claim.”

The lending bank makes no payment of anything in settlement. The target bank just becomes the depositor in the lending bank at settlement time – or they swap that obligation with somebody else in the market. But somebody ends up holding the new deposit and it cannot be avoided in aggregate – if the payment system is to clear.

There is no prior limiting factor here. The bank treasury department is just trying to improve the bank’s margin, which it does based upon the sales pipeline cashflow forecasts.

” It is these that will finance the obligations it has to the system as a result of making loans and the loan monies being spent.

Bank A’s debt liabilities are replaced by deposits.”

OK, I get your argument.

But you are implying (prior?) *need* for those deposits, rather than accepting that, because those deposits will happen *as a matter of course*, and inevitably, as a result of continuous bank lending by the banking sector (as well, crucially, direct govt spending), there is never, barring totally unrealistic circumstances we have described, any actual issue in accruing – let alone actively *attracting* – deposits, as the system, as a whole, automatically supplies them anyway – and in fact cannot really do otherwise.

Sorry, but, if I have interpreted your argument correctly, I feel that your point is just diversionary, and doesn’t accurately reflect the mechanics of the way loans create deposits, and the necessary flows between banks that result *automatically*, and without the necessity for any form of “demand pull” for deposits on the banks’ part.

Mr. S.,

I don’t believe my argument is “diversionary”.

And my example was at the margin – one loan and the consequent go-around – it was about simplifying my argument.

In reality, there is as you describe, the ebb and flow of payments in settlement of claims and obligations between banks on a net basis, on a daily basis.

There is also the ebb and flow of deposits between banks.

If it was not for this flow of deposits banks would have to fund their obligations with debt or from cash reserves. A bank could choose to not take deposits but then it would have to fund its obligations to the system with debt or cash reserves depletion. It would then have to consider the impact on its funding costs and profitability.

So loans might create deposits but deposits fund interbank obligations and it could also be said, loans.

It seems to me this is a symbiotic relationship. Banks have to have one eye on the flow of deposits so that they can optimize their profitability.

Then there is the question of the significant short and long term debt banks hold in their liabilities.

Why is it there?

It is arises because banks make conscious decisions to raise such finance.

Several Australian banks have raised billions of dollars from long term debt issues, stating specifically that this debt will fund loans to green enterprises.

Why do this? Is it a public relations exercise? Are they optimizing their funding/risk profile? Why not just grant the loans and wait for the deposits to flow?

And why is it that banks talk about retail and wholesale funding and never say things like “we pulled $20B from the air last financial year”?

Henry: “… and never say things like “we pulled $20B from the air last financial year”?”

I often read from Bill’s articles that banks lend to creditworthy customers. Banks can always provide the funding not the other way around. I also got this especially from when he explained about the misunderstanding many people have about the QE process.

I believe this case is no different. When the bank underwrites the loan above, it is out of thin air (this is how the bank balance sheet works – loan equals deposit). And this loan, which sits on the assets side of the balance sheet, can move the reserves up and down when that deposit get move around the inter-banking system.

Otherwise, the deposit is just an imaginary number and the net reserves position of the loan issuing bank will always remains the same regarding this loan).

When the time comes that the deposit actually get moved around, if there is not enough liquidity/reserves (not the money yet), how the banks provide for that is purely a routine mechanical process through the overnight lending market.

This also means how bank communicates to the public is just a charade.

Unless that project is backed in some way by the government, then, that might be a different matter.

vorapot,

“…the deposit is just an imaginary number…”

If the bank did not take deposits how would it fund its obligations to the system which arise from loan monies being spent?

(And remember, as a borrower draws down the loan funds in his account the account will go to zero credit. So at any point in time, the bank would only have as deposits those accounts from which the loan monies had not yet been drawn down.)

Dear Henry,

“and remember…. had not yet been drawn down”.

And how would the bank fund the loan?

It is about reserves management by the bank (numbers).

Deposits are not yet money (banknotes, coins), they are reserves parked at the central bank. If there are too much reserves at the end of the day, they will be long gone by being lent out in the overnight market. They would not be sitting around waiting for any loan.

When we talked about monies being spent, if it is spent in the system (moving within the bank or in the inter-banking system), it is also about reserves management.

Thus, the deposits that have not been drawn down will not be sitting around, they are just numbers in the accounts.

And let’s say, if one wants to withdraw all that deposit into cash, the bank sometimes say that you have to come back later (for a large amount) as it needs time to get more cash from other branches.

Otherwise, it is all about balance sheet/reserves management in the system (moving around numbers on spread sheets).

vorapot,

“And how would the bank fund the loan?”

The bank doesn’t directly fund the loan, it has to fund the claims coming back to it from the system as the loan monies are spent. It does this by borrowing or by depleting cash reserves. Eventually, it has the option of allowing the natural flow of deposits to it to replace any debt or replenish cash reserves.

“It is about reserves management by the bank (numbers).”

How is it that reserves are only a fraction of the loans outstanding?

It is deposits which eventually fund the obligations of banks arising from the making of loans.

Take a look at the financial statements of any organization whose business is predominantly pure banking.