In the annals of ruses used to provoke fear in the voting public about government…

Bond investors see through central bank lies and expose the fallacies of mainstream macroeconomics

It’s Wednesday and I usually try to write less blog material. But given the holiday on Monday and a couple of interesting developments, I thought I would write a bit more today. And after that, you still get some great piano playing to make wading through central bank discussions worth while. The Financial Times article (January 4, 2021) – Investors believe BoE’s QE programme is designed to finance UK deficit – is interesting because it provides one more piece of evidence that exposes the claims of mainstream macroeconomists operating in the dominant New Keynesian tradition. The facts that emerge are that the major bond market players do not believe the Bank of England statements about its bond-buying program which have tried to deny the reality that the central bank is essentially buying up all the debt issued by the Treasury as it expands its fiscal deficits. This disbelief undermines many key propositions that students get rammed down their throats in macroeconomics courses. It also provides further credence to the approach taken by Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

Central bankers caught out

For years now, the ECB Board members have been out there trying to deny the obvious.

Economists have joined in the charade because to admit the obvious would expose the whole scam.

While the Bank of Japan began their large bond-buying exercise in the early 2000s, it wasn’t until the GFC that other leading central banks joined the party.

In Europe, the ECB, faced with the insolvency of many Member States of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), moved outside the legal limits of its operations under the various Treaties, and, in May 2010, introduced the Securities Markets Program (SMP) whereby they began buying up unlimited volumes of national government debt in the secondary markets.

They clearly should have done that sooner – back in 2008 – and the European Commission should have immediately suspended the Stability and Growth Pact provisions.

At that time, if the ECB had have announced that they would support all necessary fiscal deficits to offset the private spending collapse things would have been somewhat different for the GFC experience of the 19 Member States.

The former decision could have been justified under the ‘exceptional and temporary’ circumstances provision of Article 126 of the TFEU relating to the Excessive Deficit Procedure.

It was clear that the situation was ‘exceptional’ and with appropriate policy action would have been ‘temporary’. The Council had already demonstrated a considerable propensity to bend its own rules.

However, the ECB’s intervention came too late to curb the damage and was accompanied by moronic conditionalities, which morphed into the oppression dished out by the Troika (ECB, EC and IMF) on Greece and other nations suffering massive recessions.

If the SMP had been introduced in 2008 rather than 2010 and without the conditional austerity attached, things would have been much different.

No Treaty change would have been required for either of these ad hoc arrangements to be put in place.

While obviously inconsistent with the dominant neoliberal Groupthink in Europe, these policy responses would have saved the Eurozone from the worst.

Fiscal deficits and public debt levels would have been much higher but, in return, there would have been minimal output and employment losses and private sector confidence would have returned fairly quickly.

The response of the private bond markets would have been irrelevant.

The fact is though, that the ECB was out there buying up the debt issued by the Member States and suppressing bond yields in the process.

2

That began in earnest on May 14, 2010 when the ECB established its Securities Markets Program (SMP) that allowed the ECB and the national central banks to, in the ECB’s own words, “conduct outright interventions in the euro area public and private debt securities markets” (Source).

This was central bank-speak for the practice of buying government bonds in the so-called secondary bond market in exchange for euros, that the ECB could create out of ‘thin air’.

Government bonds are issued to selective institutions (mostly banks) by tender in the primary bond market and then traded freely among speculators and others in the secondary bond market.

The action also meant that the ECB was able to control the yields on the debt because by pushing up the demand for the debt, its price rose and so the fixed interest rates attached to the debt fell as the face value increased.

Competitive tenders then would ensure any further primary issues would be at the rate the ECB deemed appropriate (that is, low).

What followed was pure pantomime.

After the SMP was launched, a number of ECB’s official members gave speeches claiming that the program was necessary to maintain, in the words of Executive Board member, José Manuel González-Páramo during a speech delivered on October 21, 2011 – The ECB’s monetary policy during the crisis:

… a functioning monetary policy transmission mechanism by promoting the functioning of certain key government and private bond segments …

In other words, by placing the SMP in the realm of normal weekly central bank liquidity management operations, they were trying to disabuse any notion that they were funding government deficits.

This was to quell criticisms, from the likes of the Bundesbank and others, that the program contravened Article 123 of the TEU.

In early 2011, the fiscally-conservative boss of the Bundesbank, Axel Weber, who was being touted to replace Trichet as head of the ECB, announced he was resigning, ostensibly in protest of the SMP and the bailouts offered to Greece and Portugal.

On October 10, 2010, Axel Weber, a ECB Executive Board member, told a gathering in New York that the SMP was “blurring the different responsibilities between fiscal and monetary policy.”

Another ECB Executive Board member, Jürgen Stark also resigned in protest over the SMP in November 2011. He clearly understood that the ECB was disregarding the no bailout clauses that were at the heart of its legal existence.

The head of the Bundesbank, Jens Weidmann also was critical.

He knew that the SMP was what he erroneously called “monetary financing”.

In a speech given to the SUERF/Deutsche Bundesbank Conference in Berlin on November 8, 2011 – Managing macroprudential and monetary policy – a challenge for central banks – he noted that:

One of the severest forms of monetary policy being roped in for fiscal purposes is monetary financing, in colloquial terms also known as the financing of public debt via the money printing press. In conjunction with central banks’ independence, the prohibition of monetary financing, which is set forth in Article 123 of the EU Treaty, is one of the most important achievements in central banking. Specifically for Germany, it is also a key lesson from the experience of the hyperinflation after World War I. This prohibition takes account of the fact that governments may have a short-sighted incentive to use monetary policy to finance public debt, despite the substantial risk it entails. It undermines the incentives for sound public finances, creates appetite for ever more of that sweet poison and harms the credibility of the central bank in its quest for price stability. A combination of the subsequent expansion in money supply and raised inflation expectations will ultimately translate into higher inflation.

Whatever spin one wants to put on the SMP, it was unambiguously a fiscal bailout package.

Weidmann was correct in that sense.

The SMP amounted to the central bank ensuring that troubled governments could continue to function (albeit under the strain of austerity) rather than collapse into insolvency.

Whether it breached Article 123 is moot but largely irrelevant.

The SMP reality was that the ECB was bailing out governments by buying their debt and eliminating the risk of insolvency.

The SMP demonstrated that the ECB was caught in a bind.

It repeatedly claimed that it was not responsible for resolving the crisis but, at the same time, it realised that as the currency-issuer, it was the only EMU institution that had the capacity to provide resolution.

The SMP saved the Eurozone from breakup.

And, of course, this sort of behavour by central banks is now the norm.

Which is why a recent article in the Financial Times (January 4, 2021) – Investors believe BoE’s QE programme is designed to finance UK deficit – is interesting.

Note that Chris Giles (one of the co-authors of the article and Economics Editor at the FT) has been tweeting about the big U-turn from the OECD (which I will write about soon) supporting fiscal dominance and rejecting almost all of the claims that that organisation pushed for years about the benefits of austerity.

It seems that Mr Giles, one of the leading austerity proponents in the financial media, is also undergoing somewhat of an epiphany, as are many who are desperately trying to get on the right side of history, as the paradigm in macroeconomics shifts towards an Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) understanding.

The FT article relates to the bond-purchasing program of the Bank of England.

In the same way that the ECB officials denied what they were doing, the Bank of England govrnor claims that their massive quantitative easing program is about ‘inflation control’ – pushing inflation up to its 2 per cent target rate.

Of course, even that sort of reasoning reflects the flaws of the mainstream paradigm.

Central banks have proven incapable of driving up inflation rates as they increase bank reserves because the underlying theory of inflation (Quantity Theory of Money with money multiplier) is inherently incorrect.

But the FT article surveyed “the 18 biggest players in the market for UK government bonds” to see what their understanding of what the Bank of England was up to.

The results were:

1. “overwhelming majority believe that QE in its current incarnation works by buying enough bonds to mop up the amount the government issues and keep interest rates low”.

2. “most said they thought the scale of BoE bond buying in the current crisis had been calibrated to absorb the flood of extra bonds sold this year, suggesting they believe the central bank is financing the government’s borrowing.”

3. “investors place fiscal financing at the centre of their understanding of how QE works, a conviction that has strengthened in the current crisis compared with previous rounds of bond buying.”

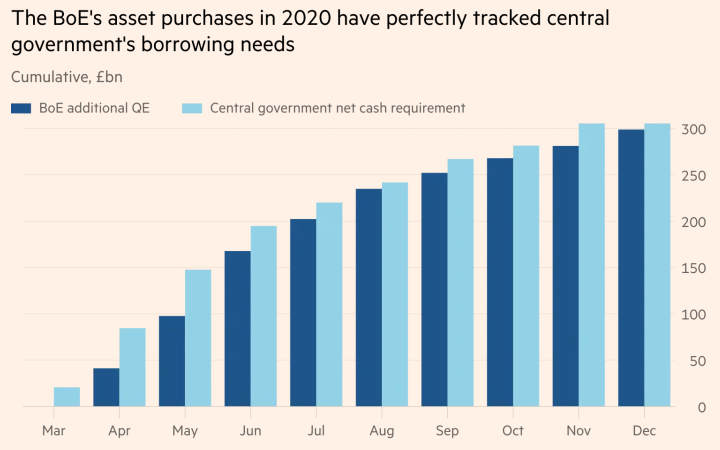

The FT article provided this graph, which tells the story:

The bottom line is that the bond market players don’t believe a word the Bank of England bosses are saying.

And this bears on the so-called arguments about central bank credibility, used by the mainstream to suppress fiscal policy and central bank bond buying programs.

Apparently, if the bond markets think the way the central bank is behaving is not ‘credible’ then rising yields and inflation will follow quickly as the markets ignore central bank policy settings.

One has to laugh.

Here we clearly have the major players in the bond markets outrightly disbelieving the central bank statements and clearly understanding exactly what the bank is up to, yet yields stay around zero and there is no inflation remotely in sight.

The FT revealed that the survey respondents also did not believe the line pushed by New Keynesians (mainstream macroeconomists) that the Bank bond purchases would drive inflation up.

One respondent said:

While the idea of raising inflation expectations, to help reach the bank’s target of actual inflation, is very popular, it is arguably less clear to what extent central banks can really influence inflation expectations and actual inflation.

The game is well and truly up!

Music – Hymn to Freedom

This is what I have been listening to while working this morning.

It is a piano piece that I like to sometimes play on my own as a sort of practice routine.

The song – Hymn to Freedom – first appeared on the 1963 album – Night Train (Verve) – released by the incomparable Canadian pianist – Oscar Peterson – with the other players in his trio comprising:

1. Ray Brown (Acoustic double bass).

2. Ed Thigpen (Drums).

The whole album is one of the best out there.

Oscar Peterson wrote the song in support of the civil rights movement in the US in the early 1960s.

On the Freedom reference, which isn’t why I was listening to the album today, I saw that Kamala Harris is once again in the spotlight for a story about her childhood where she appears to rip-off an anecdote from Martin Luther King. It doesn’t augur well for the next administration in the US. See this story if you are interested – Kamala Harris’ ‘Fweedom’ story mirrors MLK account (January 4, 2021).

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2021 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“But the FT article surveyed “the 18 biggest players in the market for UK government bonds” to see what their understanding of what the Bank of England was up to.”

Given those players in the market also deal with the Debt Management Office, they have the complete view of what is happening.

The DMO turns up every day and executes a set of Repos – issuing Gilts to drain the money HM Treasury has added to the banking system with its spending that day – particularly at the moment. Gilts the DMO gets freshly issued from the National Loans Fund whenever it needs some more. The DMO annual review shows that the DMO runs primarily on Repo Gilts for the majority of year and *drains them for more permanent issues via the Gilts auctions*. The difference is that the former is ‘cash management’ and the latter is ‘debt management’ – ie they have difference process titles.

Then the Bank of England turns up periodically and swaps them back for money.

The only people who still pretend to believe the fairy dance appear to be those in charge of the Bank of England, the Debt Management Office and whoever from HM Treasury is giving those two institutions their terms of reference.

The underlying structures of the British government system are pure MMT. We have permanent intra-day and inter-day government overdrafts without limit at the Bank of England and have for at least 150 years. Everybody in power knows it, and they are pretending they don’t.

It turns out the longest running British Farce isn’t in the West End. It’s between Horse Guards Road and Threadneedle Street.

“That began in earnest on May 14, 2020 when the ECB established its Securities Markets Program …”

Should that be 2010?

Brilliant, Bill. That Weimar hyperinflation has really scarred German macroeconomics. First the 1930s austerity and then the EU in the first place! How long can the EU and the likes of the RBA persist with QE before the reality becomes too untenable to resist? The jig is surely just about up.

Dear Allan (at 2021/01/06 at 4:37 pm)

Yes, thanks very much. Fixed now.

best wishes

bill

The question at the bottom of the WaPo article asks us why politicians plagiarize when there is a reasonable chance of being caught?

Answer is, same reasons it’s so difficult for people to see through the big problems with mainstream macroeconomics. There is a strong tendency to trust people who appear to be in positions of authority (think Milgram’s experiment), choosing to believe that anyone in such position must have gotten there by merit alone.

That and few people can recall or correctly attribute an old quote to the original author.

If it isn’t those reasons the alternate answer is downright frightening.

In my experience, politicians don’t even respond to questions regarding their positions on fiscal matters if your correspondence makes it look like you have acquired the MMT perspective. They know that most of the electorate don’t have that perspective yet and believe they can afford to be that arrogant with you to keep the game going.

In one instance however, a gate keeper did inform me that he might actually let the minister see my letter. It’s been a couple of years now with no reply.

Nevertheless, I will write again to ask why the government wants to further deplete private savings and spending by/of all working people by increasing the required amount they must contribute to the Canada Pension Plan in the midst of an economic crisis brought on by the pandemic. Wish me luck.

Great article.

Thanks for reminding me of the Milgram experiment. Great tool to use when we try to prove a point.

Good luck on your writing.

I’m intending to take part in this:

“Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey returns for our third virtual Citizens’ Panel Open Forum… Members of the Citizens’ Panel community are invited to join the session to hear directly from the Governor and to take part in a live Q&A.

This session will explore the financial landscape as we head in to 2021 and will look at the important role the Bank plays in maintaining financial stability during these uncertain times.

Questions on this theme can be submitted in advance via the registration form or live during the session.”

I’m looking for a ‘trick’ question to ask – probably live, so they might be tricked. Could anyone suggest something, please. I thought of making a reference to Giles’s FT op ed.

There are a couple of us in the UK who are registered on these Bank of England Citizens Panels.

We must not assume that the opponents are stupid. It gives them an advantage. It’s not unreasonable to presume that many, if not most, people in positions of influence do understand how money works. Some of them observe the mechanics, the process and the outcomes on a daily basis. My view is still the same. One can’t separate economics, politics and ideology. All three are part of the whole. If something doesn’t make sense from economic point of view change your angle. Does it make sense from political or ideological perspective?

If Corbyn was in power now then the media hysteria about the ballooning debt arising from the pandemic would be intense. The British Labour government would be treated and portrayed as a pariah just as Greece was and still is.

The Conservatives would be atracking the profligate Labour Party and calling for budget repair and structural change. The Blairite’s in the party would probably agree, panic about the plunging opinion poll results and topple Corbyn and continue futher down the neoliberal path.

The central bankers, world of finance, the oligarchy and their corporate mass media have clearly reserved Keynesian fiscal stimulus and QE government debt elimination for their chosen pro business or conservative parties exclusive use and even then only when most of the stimulus funding goes directly to the wealthy and only just enough of the underclass wage earners so as to keep the stock and real estate markets in the black.

The oligarchy clearly knows what economic policies work and have clearly decided to reserve those policies for the exclusive use by their chosen political parties.

Capture of the prevailing economic environment and of governments by the 0.1% is almost total.

@Carol Wilcox, Thursday, January 7, 2021 at 8:45

This is something I puzzle about..

(After reading the excellent and very interesting article by Bill and all the good comments above, as well as the FT article itself), I would ask – “are you, or the BoE, going Japanese? Meaning, keeping policy interest rates and bond yields (permanently) low, as the fiscal deficit situation might be a prolong one?

If so, how would you reckon, or, what will happen to the government and private pension schemes and other similar insurance schemes that rely on interest payments?

How will they remain solvent in such environment? And how will this affect the country’s financial system as a whole, as it is a big industry in our financial sector”

I would also appreciate anyone who takes a shot… (as I learn from a private insurance expert that some of the schemes her company sold sometimes ago are or will begin to lose money on their maturities (due to a very low interest rate trend in my country).

Thank you all in advance!

Re Lavrik:

I agree completely and would add an additional point. Austerity economics means the reduction in the size of the government sector and an increase in profit opportunities for private capital. The expansion of private capital serves the financial interests of corrupt politicians when they receive favours for their prior service. In the province of Ontario here in Canada a former Premier of the province has personally benefited from the privatisation of long term care homes. Mike Harris became CEO of a large private chain one year after changing the law allowing more private investment in the sector. He is paid ca. $230,000 yearly. This practice is an add-on to the long-standing practice of placing former compliant politicians on the Boards of Directors of companies.

Vorapot: some of the private pensions have foreseen the problem you mention, and have begun to move toward direct ownership and management of their investments, rather than only being passive investors who buy equity and debt instruments as in the past.

They have actually been pretty good at this and have in some cases done more to advance progressive causes than most governments. This is clearly the only way forward for them.

Governments do not need to fund a pension fund through investment in private markets. That is as much a case of corporate welfare as the sale of government debt instruments.

Read some of Michael Hudson’s stuff to get some perspective on the insurance industry as part of the FIRE ( Finance, Insurance, Real Estate) sector before shedding too many tears of sympathy.

“It’s not unreasonable to presume that many, if not most, people in positions of influence do understand how money works. ” I couldn’t agree more Lavrik.

My view today is that they have always known how money works, and it’s been one of the best kept secrets until Bill and others started “spreading the word”.

The powers and those who help put them there, seem to use spending and taxation as their own carrot and stick to make the donkey (the rest of us) follow their will.

J Christensen, Friday, January 8, 2021 at 4:51

Thank you for the insights especially for connecting the dots here… “Governments do not need to fund a pension fund through investment in private markets. That is as much a case of corporate welfare as the sale of government debt instruments”.

How could I overlook that! (I guess from what we are fed day-in day-out on… the government pension schemes will run out of money in years so and so if we don’t tighten up or spend less).

I will read Hudson’s, and now, with ease, knowing that there is no great financial crisis lurking in the near or distant future by this sector, knowing how they cope.

(And, come to think of it, how can they… if the governments, like Japan or the ECB, can back stop anything they want to as clearly pointed out by Bill in the above, as well as in other similar countless posts).

I know Michael Hudson from the LVT movement primarily. The solution to the real estate problem is easy, but he is reluctant to mention it. That maybe because it’s not so easy in the US with its multi-tier taxation system. But there are other reasons, I know.

The problem is purely political not practical.

Carol, how about asking the BOE technocrats why they don’t comply with their own mandate to ensure full employment?

Ask them if they understand what NAIRU (non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment) is and then ask them if they know what NAIBER (non-accelerating inflation buffer employment ratio) is?

Then ask why does the BOE not advocate for NAIBER to replace NAIRU?

Finally does the BOE think it fair that the unemployed be so harshly treated by successive government’s social welfare policies when the BOE maintains or creates a target level of unemployment using monetary (interest rate) policy?

The source information can be found in the Wikipedia article on the Job Gurantee under the inflation control section.

J Christensen your comments I agree with.

Thanks, Andreas, but those are questions which they will not choose to address. This is probably a waste of effort, but I’m willing to give it a try. We have at least one other MMTer prepared to ask a ‘trick’ question.

Got to ask what the purpose is really – to reveal their ignorance? There’s an opportunity then to publicise.

Carol perhaps you could provide questions to the BOE people prior so they can at least study up and think a bit about the issues. They have a duty to serve the British people not just the usual insiders and powerful elites.

Carol how about what percentage of government debt issued in 2020 is owned by the

BOE and does this ever have to be paid back?

I like that, Kevin. I shall submit it on the day. I don’t agree with Andreas about giving them time to study it – as if…

Any further qs welcome as there’s another one of us on the call.

heres a question you can ask carol,

whats more inflationary, government financial deficits with bond issuance, or government financial deficits without bond issuance.