These notes will serve as part of a briefing document that I will send off…

Britain is now free of the legal neoliberalism that has killed prosperity in Europe

So Britain finally became free – sort of – from the European Union last week. I haven’t fully read the terms of the departure but the progress I have made so far in the text (several hundred pages) leads me to conclude that Britain has not gone completely free from the corporatist cabal that is the European Union. The agreement will see a Partnership Council established which locks Britain in to an on-going bureaucratic process dominated by technocrats – the sort of things the EU revels in and gets it nowhere. Overall, though, despite all the detail, Britain’s future policy settings will be guided by its polity and resolved within its own institutions. That means that the Labour Party has the chance to really push a progressive agenda. I doubt that it will but there are no excuses now. Which brings me to look at some data which shows how the fiscal rules imposed by the European Union, particularly in the 19 Member States who surrendered their currencies, have constrained prosperity and worked against everything that citizens were told.

The relaxed Stability and Growth Pact

There are some progressive economists who claim that with the relaxation of the strict fiscal rules in the Eurozone coupled with the ECB’s massive PEPP program, there is little difference between being a formal currency issuer, like the US, Japan, or Australia and the 19 Member States of the EMU.

The data from the latest – IMF Fiscal Monitor – (published October 14, 2020) is revealing in this regard.

The first graph shows the Discretionary Fiscal Response to the COVID-19 Crisis in Selected Economies measured by the “Additional spending and foregone revenues”.

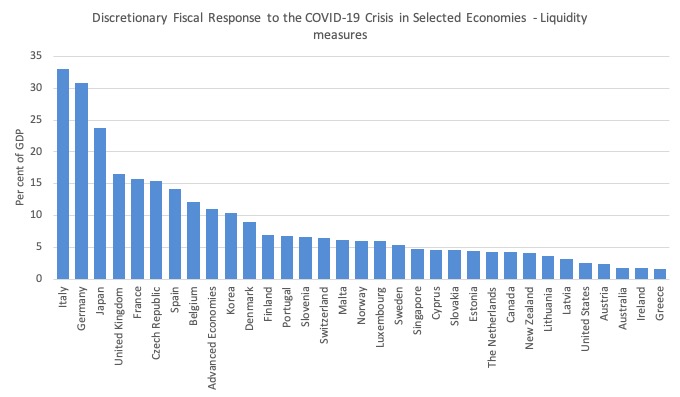

The second graph shows the fiscal response in terms of Equity, loans and guarantees – that is, so-called liquidity measures.

In general, the first class of stimulus measures are more direct and have higher multiplier effects than the liquidity measures.

I ranked the nations by size of stimulus and the smaller stimulus nations are predominantly Eurozone Member States (red bars).

The second graph shows that the EMU Member States are more engaged in liquidity measures – which are usually highly conditional and have to be paid back when growth returns (or does not return).

Liquidity measures tend to constrain flexible policy choice, which is why the European Commission favours them.

It could be argued that the stimulus need in the Eurozone was less than in the other nations shown in the first graph that injected considerable fiscal stimulus to support their nations through the pandemic.

Also remember that the fiscal outcome is endogenous and not controlled by the government’s discretionary choices.

Why? The final balance is partly determined by the level of activity (because tax revenue and welfare outlays are sensitive to activity). So nations that provided large fiscal support might have been responding to a massive collapse in output.

I am still working on the data at present and will report later on what I have found about the relationship between the additional spending and foregone revenue data and the real GDP growth.

But what appears to be the case is that while the Stability and Growth Pact rules have been temporarily relaxed, the Member States have not increased their deficits nearly as much as many other non-EMU nations, some of which appear in this IMF dataset.

I am guessing that the culture of austerity is now so embedded after twenty years of Eurozone membership that ambition has been quelled and governments are now prepared to oversee sub-standard outcomes.

The alternative hypothesis, which doesn’t necessarily contradict that conjecture, is that these nations know full well what will happen when Brussels decides to return to the Excess Deficit Mechanism and start demanding a renewed bout of austerity.

So, staying as close to the rules as possible eases future hardship.

Then consider the evidence

In February 2019, the Centres for European Policy Network (cep) published a report – 20 Years of the Euro: Winners and Losers: An empirical study – which created a controversy.

Why?

Because the results demonstrated how badly countries had fared as a result of their membership of the Economic and Monetary Union.

The question the study sought to answer was:

How high would the per-capita GDP of a specific eurozone country be if that country had not introduced the euro?

The study used the so-called “synthetic control method”:

… to analyse which countries have gained from the euro and which ones have lost out.

The technique used by the cep-researchers is summarised as follows:

1. Create a ‘control’ group – with overtones to the authority that research in the physical sciences, which unlike social science, can conduct properly ‘controlled’ experiments.

This means “the actual trend in per-capita GDP of a eurozone country can be compared with the hypothetical trend assuming that this country had not introduced the euro (counterfactual scenario).”

The counterfactual is quantified by what happens in the ‘control group’:

… is generated by extrapolating the trend in per-capita GDP in other countries, which did not introduce the euro and which in previous years reported very similar economic trends to that of the eurozone country under consideration (control group).

2. The non-Eurozone nations that comprise the control group are then weighted – 0% to 100% – according to how each nation in the group “closely resembles the trend in per-capita GDP of the eurozone country before it introduced the euro.”

These weights are purely statistical and instrumental.

3. They create those statistical ‘fits’ for data between 1980 and 1996 (that is, before the convergence process started to kill growth in the Eurozone nations).

4. The highest weighted nations in the second part of the process (post Euro introduction) are those that match the growth trajectory of the Euro nations (pre-Euro).

5. A comparison is made post-euro between the growth predicted for the control group (according to the weightings) and the growth of each euro Member State, and the difference is attributed to the decision to join the EMU.

I have commented on this statistical technique previously in relation to British studies that tried to use it to say that Brexit would be disastrous.

See this blog post – How to distort the Brexit debate – exclude significant factors! (June 25, 2018).

You can learn about the technique from this page – Synth Package. I have worked with the software myself (R-version) and while it is rather speculative there are useful results that can be delivered as long as the ‘weightings’ are not distorted and recognising that exogenous factors (those not taken into account during the post-control period) could be influential.

My criticism of the use of this approach in the Brexit context was exactly because the researchers had ignored (probably deliberately) the conduct of fiscal policy (pre- and post-Referendum).

The researchers ask:

… how much higher or lower their per-capita GDP would have been, in 2017 … and overall … if they had not introduced the euro.

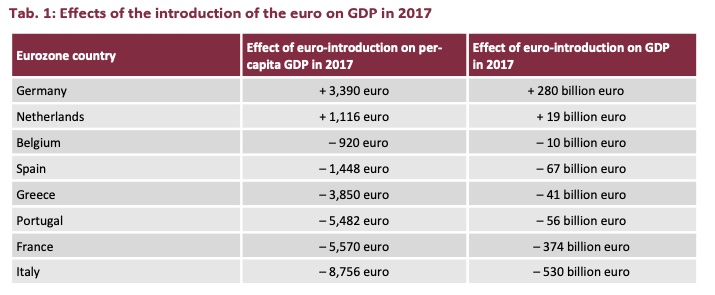

The results are summarised by the following Table:

They are self-explanatory and devastating.

They write:

In 2017, out of the examined eurozone countries, only Germany and the Netherlands gained from the euro. In Germany, GDP went up by € 280 billion and per-capita GDP by € 3,390. Italy lost out most. Without the euro, Italian GDP would have been higher by € 530 billion, which corresponds to € 8,756 per capita. In France, too, the euro has led to significant losses of prosperity of € 374 billion overall, which corresponds to € 5,570 per capita.

The situation will have worsened over the last three years since the dataset they used ended.

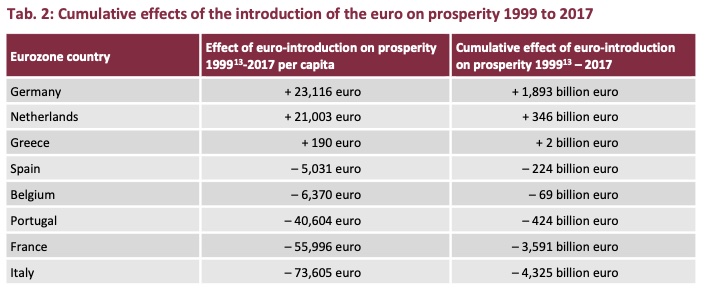

They also computed a cumulative gain/loss table “for the entire period since the year of introduction – 1999 in all countries except Greece, for Greece 2001 – until 2017.”

So if you live in France, each citizen (on average) was worse off by 55,996 euros by 2017. Italy even worse – minus 73,605 euros on average per person.

Definitely not convergence.

Definitely not prosperity.

Definitely not a short-term phenomena.

Definitely entrenched in the institutional and legal structure of the monetary system.

On March 1, 2019, cep.eu put out a rather extraordinary press release – Statement on reactions to the study 20 years of euro – to address what it said was a “highly political environment”, which had led to the study receiving a “large number of reactions”.

They sought to clarify some points.

They were obviously attacked for providing evidence to show the EMU had failed and the logical inference was that nations should leave.

The organisation responded in this way:

The results of the study do not show that it would be better for a euro state to withdraw from the euro. On the contrary, those euro states that have not yet benefited from the euro must carry out reforms, particularly to increase competitiveness, in order to benefit from the euro. This was pointed out several times in the study. Withdrawing from the euro would entail unmanageable risks and would not therefore result in an improvement in prosperity for any of the countries as compared to the status quo. Reforms are therefore the only alternative.

Which I thought was an amazing demonstration of the Eurozone Groupthink that I highlighted my 2015 book – Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale (published May 2015).

Well, if you read the report carefully they say things like:

1. “In the decades prior to introduction of the euro, France regularly devalued its currency for this purpose. After the introduction of the euro, that was no longer possible. Instead, structural reforms were needed.”

2. “Italy has still not found a way of becoming competitive inside the eurozone. In the decades prior to introduction of the euro, Italy regularly devalued its currency for this purpose”.

In other words, cep.eu cannot conclude that nations will always be better off within the EMU as long as they introduce structural reforms.

These reforms involve cutting job protections, wage levels, pensions, increasing work hours, etc

All things that make PEOPLE worse off even if national income may or may not increase.

They redistribute whatever national income is produced increasingly towards to the top end of the distribution and away from the workers.

If a nation left the EMU and allowed its exchange rate to resolve productivity and cost differences, I believe it would be far better off than remaining in this neoliberal grinding system that so far has only destroyed prosperity for most of the Member States.

Conclusion

Britain has left the EU.

That means it has left an organisational structure that has neoliberal ideology embedded in the very legal foundations of the system.

It does not mean, clearly, that is has abandoned its own neoliberal leanings.

But now that ideology is operating at the political dimension rather than at the foundation of the monetary system.

That means, that a progressive Labour Party (or a reformed Tory Party) can move beyond this neoliberal period that has damaged prosperity and social cohesion to adopt much better policies towards sustainable growth, public infrastructure, public health and education and more.

It is no longer bound by a ‘legal’ neoliberalism. It is all at the political level now.

Sadly, the Labour Party doesn’t appear to be capable of taking up that challenge.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2021 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Hi Bill,

I hate to be ‘that guy’…but your first par should say “their currencies”, not “there”. 😉

The Labour Party is now dead and beyond hope it seems having fully ousted the Left and dancing around the culture wars dictated by the Tories.

Well, I suppose we have a ‘reformed Tory Party’ but one that will be rentier on steroids, it seems.

We’ve already had them using the Covid-crisis to:

1. Hand out massive corporate bungs, in some cases to Tory Party affiliates and even family. The minister responsible for Vaccines has already set up his own ah hem…’medical business.’

2. Housing has been bubbling due to stamp duty relief so we can expect more wealth extraction and asset bubbling here.

3. 1% still own over 50% of the land, so not much’taking back control there.’

4. Look like a developers’ wild west is in the offing which will assist further bubbling.

5. Sunak already doing the deficit hawk shuffle.

6. Evidence already of ‘pork barrel politics’

7. Evidence of deregulation of environmental safeguards a la Trump.

8. All this combined with culture war ‘furphys’ about Marxists everywhere (has anyone seen one?) and positing themselves as the defenders of freedom (probably defined as freedom to grift. graft and scam).

9. Covid used as an accelerant towards private health insurance as NHS is overwhelmed. Ministers already bad mouthing NHS preparing the ground for private health to expand.

10. Despite the need for 3.1 million social homes, Tories still touting the ‘housing ladder’ and home-ownership dividing the working class into house owners v. renters and what remains of social housing-the latter seen as ‘losers.’

But who knows, I might be wrong and a much touted ‘national resurgence ‘ is on the way.

Portugal main political parties mantain the SMU mantra on their agenda.

While these deadmeat people are not run off of office, there will be no hope of following the brexit example.

The right wing is loosing votes everyday, so they are morphing in new populist and xenophobist guises to deceive voters.

I’m fully on-board with a country maintaining sovereignty over its own currency and thus not being a member of the eurozone. I don’t understand why membership in the EU (while maintaining sovereignty over the nation’s currency) is, on balance, a bad thing? Can anyone please explain?

@ Neil,

It isn’t realistic to expect the problems of the euro to be totally constrained within eurozone borders. They will spill over and affect other EU countries too. Leaving the EU still doesn’t give full protection but it provides some. It would clearly be beneficial for the UK, even when outside of the EU, if the EU was in a much healthier state.

There are also longer term considerations. If the EU is as unstable as Bill’s analysis leads me to believe it is, the risks of chaotic disintegration are high. Being out of the EU will help to an extent when and if that happens. On the other hand, if the EU does manage to find some sort of stability it will have to be as it moves towards a United States of Europe. I would say that’s unlikely, but even so I wouldn’t want to be a part of it.

I think it depends on who you ask. Would you say people in Russia lose or gain from current regime? What about China or North Korea? How about USA? Venezuela? Saudi Arabia? Maduro has all but ruined the country. Yet he is still in power and gained handsomely in material terms. Putin and pals have been robbing their people for decades. Still standing. Did Saudi family bring prosperity to the subjects? Which ones? USA is a famous democracy presumably founded on principles we all can get behind. The ‘official’ poverty rate is %10 with even greater number of simply poor. Clearly prosperity is not evenly distributed. So, what do all these disparate examples have in common? They are regimes put in place by specific people for specific reasons. I would argue that there is a great variety of regimes which once implemented will make the designers better off, frequently at the expanse of everyone else. EU is one of them. Admittedly, some regimes are more humane than others. My point still stands. There is always a small group of architects and pals thereof who benefit from the arrangement. From this angle EU works exactly as intended. I am also certain that designers are very happy with the results. Many probably realize that it can’t last though. Well, as long as it does.

” I don’t understand why membership in the EU (while maintaining sovereignty over the nation’s currency) is, on balance, a bad thing? Can anyone please explain?”

How do you implement a Job Guarantee if all of Europe’s unemployed can come to a country that implements it? How does your housing stock cope? There is already huge disquiet about the massive and excessive expansion of the population in many areas.

How do you control monetary sovereignty when Article 123 of the EU treaty prevents you from using your own central bank directly – requiring you to pay welfare payments to the finance industry in perpetuity?

How does a parliament implement the will of the people when corporations across Europe can go to court to override legislation by appealing to a ‘higher law’?

The EU is a technocracy ruled by judges and bureaucrats. The ECB is the defacto senate making funding decisions based solely upon monetary instruments rather than the needs of the population. It is a neoliberal kleptocracy controlled by corporate lobbyists in Brussels. I find it astonishing that anybody who cares about the working population and how they want to live their lives would consider it anything other than an anachronistic holdover from the 2nd World War.

The future is distributed, not centralised.

@Neil Wilson – spot on.

Richard Murphy and other supposed MMT/EU-supporters could do with reading that.

The UK has to keep to a level playing field agreement on what it can invest in British business and welfare etc so is still subject to EU rules and has completely NOT escaped neoliberalism ….

Failure to keep to this arrangement will attract sanctions and tariffs.

A while back, I made a comment to the effect that MMT might sadly have to forgo these three letters, and the words for which they stand, if it wanted to make political headway. Socialism, for example, only made a late 19th Century splash in America because Edward Bellamy refused to use the word “socialism” to describe his wildly popular vision of a radically egalitarian society. If Bill permits the link below to stand, it will provide an example of how one might effectively advocate for progressive policies, seeing through the MMT lens but not expressly saying so.

https://www.counterpunch.org/2021/01/08/austerity-democrats-and-the-state/

@Neil Wyman

This old Gruaniad article (2006) shows how the rules of the S&GP are used to put political pressure on governments even when they’re not in the Euro. I found it a real eye-opener.

https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2006/jan/11/economy.uk

Note how Vince Cable uses the higher authority of the EC to try to belittle Gordon Brown and embarass him. MPs quoted in the article are invoking the authority of the EU to label a fiscal deficit as a sign of an irresponsible government. They are using the rules of the EU to brand a Chancellor’s spending as ‘reckless’. They are using the authority and ‘unity’ of the EU to cause political damage to their opponents. Some people still maintain that it was Labour’s over-spending at this time that helped cause the GFC, as (they believe) the EC was trying to warn Brown it would. Folks still claim a Labour government would cause another economic catastrophe by spending too much ‘like last time’.

Note also the Treasury statement grovellingly conceding and explaining how ‘prudent’ it will be. Surely a government should only have to justify it’s fiscal policy to the people who elect it? Why to anyone else?

@Simon Cohen

Yep that seems to be about the strength of it.

Bill would like to see the Labour Party become more progressive, so would I, but that won’t be happening under Keir Starmer, who has a quite conservative outlook, But then I think that actual progressive politics in the UK is a very very long way away anyway. The UK is on the whole generally a conservative nation, where neoliberal ideals are deeply embedded in the national psyche.

Voting intentions I find rather illuminating – The Government’s performance during the UK pandemic has been both extremely poor, and also very obviously incompetent. Currently the two parties are neck and neck in the polls.