I am late today because I am writing this in London after travelling the last…

Why luxury watches shouldn’t be the most egregious news to come out of Canberra

Today, we have a guest blogger in the guise of Professor Scott Baum from Griffith University who has been one of my regular research colleagues over a long period of time. He indicated that he would like to contribute occasionally and that provides some diversity of voice although the focus remains on advancing our understanding of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its applications. It also helps me a bit and at present I have several major writing deadlines approaching as well as a full diary of presentations, meetings etc. Travel is also opening up a bit which means I can now honour several speaking commitments that have been on hold while we were in lockdown. Anyway, over to Scott …

Why luxury watches shouldn’t be the most egregious news to come out of Canberra

Over the past couple of weeks, the Australian government has been holding Senate Estimates Committee hearings.

Senate estimates allow members of the Australian senate (the upper house of government) to examine the financial goings on of government departments.

Officially, the Senate Estimates are to ensure the responsible spending of public money.

However, the transcripts of the committee hearings do sometimes make interesting reading if only to provide an opportunity to delve a little deeper into the business of government.

There are often revelations about how much a government department has spent on pot plants or how many paper clips they use.

Riveting stuff.

In this round we were informed that several senior executives working for government corporation in charge of Australia’s postal services (Australia Post) received luxury watches as a bonus.

The outcry within the Canberra bubble was swift and loud. During one parliamentary sitting the Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison raged about how the use of government funds, which by the government’s misguided thinking is ‘taxpayer’s money’, to buy expensive watches for senior executives of Australia Post is something that most Australians would not stand for.

The PMs reaction, and the fallout for the head of Australia Post has been filling the media for much longer than such a nothing story should.

Sadly, other issues have not been so newsworthy, nor had the Prime Minister raging in parliament.

One of the more egregious things to come out of estimates has been statements around Australia’s support for the unemployed which show just how the government’s policy decisions consign a large number of Australians to precarious living conditions.

To set the context, on – Current numbers – the Department of Social Services tells us that there are approximately 1.4 million Australians receiving the government’s jobseeker payment as at June 2020.

This has of course increased significantly throughout the COVID economic slowdown with figures from March 2020 pointing to 792,814 Australians receiving payments.

The debate around the precarious living conditions of those who are unemployed is farmed around the adequacy of the payments they receive while unemployed.

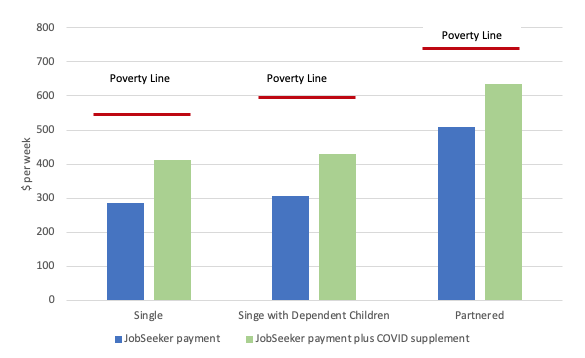

Prior to the introduction of the federal governments COVID supplement, which paid an extra $125 per week, a single person claiming jobseeker received $287.25 per week or just over $40 per day, single person with a dependent child received $306 per week ($43.70 per day), while a person with a partner also receiving benefits received $255 each per week ($36.42 each per day).

The addition of the COVID supplement in mid-2020 lifted weekly income by $125 for each recipient class.

For each type of recipient, even with the addition of the COVID supplement weekly income falls far short of a figure equivalent to the poverty rate.

The problem of poverty is of course more than just about money. Individuals and families living in poverty face increasing dislocation from society.

The local economies and communities in which these people live suffer from a lack of sustainable economic activity and falling levels of social and economic resilience.

Taken together, it is not just individuals that suffer, but the whole of society.

This context, makes the release of the transcripts from the Government’s Senate Estimates Committee interesting reading.

As part of the Community Affairs Legislation Committee, we got a glimpse of the way the government sets income support levels for the unemployed and the true policy goals of support payments.

Someway through the session, one committee member asked:

Does the government/department … work with a current definition of a poverty line for the purposes of your payments and policy work around the payments?

There was a lot of ducking and weaving on the part of those supposed to be answering the questions, but the general conclusion was summed up as the government doesn’t consider poverty or the possibility that a person might fall into poverty when setting payment rates.

Instead, the government uses a range of factors:

Different factors are often applied in this space, but we tend to consider not just what is used as a more academic definition, which is people below a median income level, because that doesn’t take into account people’s circumstances.

It is a broader consideration of what might be the factors in the person’s background in terms of other resources that they may have available to them, not just their level of income.

Then we find out that the true goal of the government’s unemployment payments is to ensure that the unemployed do not get too comfortable with their day to day existence so that they will remain hungry for work.

We hear from the minister of Families and Social Services that the:

… payment system is very comprehensive and specifically targeted towards providing the policy outcomes that are defined by the particular measures …

You would think that the policy outcomes might be around ensuring that disadvantaged Australians aren’t thrust into poverty.

Not so it seems.

The minister then comments:

What I would say is that income support payments are put in place as a safety net, to assist people who-every Australian who is of working age and is able to work we expect to be either working or looking for work, and these benefits are to provide a safety net for them during that period of time.

But:

… at the same time, don’t provide a disincentive for people to engage in the workforce.

So, there we have it.

The government’s response to supporting those Australians who have been unfortunate enough to lose their jobs is couched firmly in the typical neoliberal view that unless support for individuals is punitive, then they will lose the incentive to work and hence the booming job market that is managed so well by the private sector will not have access to workers.

In short, it is the old story that if a person is unemployed it is their fault.

If a person loses the incentive to work because of over-generous government payments, then that is not good enough and it is up to the government to ensure that doesn’t happen.

It is hard to believe that a government who prides itself on slogans such as ‘we are all in this together’ and ‘working for all Australians’ would be so shallow as to deny the unemployed adequate support because of a view that if they are receiving a supplement that raised them out of poverty, they would lose the incentive to work.

Actively pushing people into poverty as a policy choice flies in the face of good governance.

The roll of governments is to protect their citizens not economically persecute them.

The poverty story is of course broader than just those consigned to being jobless.

It impacts on Australians earning an aged pension, those referred to as the working poor including people who cannot get enough hours of work and those working in the so-called gig economy who drive people or delivery food on scooters.

Some issues of poverty, such as the plight of our older Australians living on a pension, can be easily solved by the government increasing payments to these individuals.

There would be no barrier to this, it just needs political will and a few keystrokes.

The precarious position unemployed people find themselves in requires a different approach.

Although some have suggested the introduction of a Universal Basic Income to alleviate poverty, such schemes have been shown to be ineffective as a poverty alleviation tool.

As the driving factor in poverty for the unemployed is lack of a job, then the government has a role to play by introducing a Job Guarantee scheme.

Such a scheme, as we know, would provide a job for everyone who wished to work at a socially sustainable income level.

The result would be an immediate reduction in poverty experienced by those who are unemployed, an increase in resilience in local economies and communities as more people became engaged in the economy and society and a reduction in the associated social malaise that comes from the dual problems of unemployment and poverty.

In doing so, the government could move some way towards acting as if they really did care for all Australians.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2020 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Letter in Toronto Star

https://www.unpublishedottawa.com/letter/309829/spending-create-jobs-economically-efficient

Spending To Create Jobs Is Economically Efficient

Excerpt:

“The government can target expenditures to ensure that everyone who wants a job can be offered one either by the market or by a Job Guarantee (JG) program that provides a livable, minimum income. JG community work could include help to the aged, public arts, and environmental stewardship. A fully functioning economy means vastly reduced poverty and a general increase in living standards.”

Not to mention the proposed wage freeze and wage reductions under the disguise of stimulating the economy….

It’s likely, the punitive neoliberal way costs most of society a lot more than it increases the bottom line for firms. This is the part I have trouble understanding why most people can’t see .

in my community (in Ontario, Canada), the municipality recently built a shelter to house the portion of homeless people who had built a tent city on vacant city property. They were in plain view for all passerby to see.

Upon the opening of the shelter, the grocer across the street from the shelter immediately saw the rate of theft of his produce skyrocket, duh. What then happens to the price paid by the consumer?

What to do? Put them in Jail? This usually comes with a local price as well; and, then upon release, the offender has a criminal record, which precludes the possibility of ever finding a satisfactory job.

Being punished for being poor, in a world were there are too few jobs, results in a Robin Hood mindset were crimes committed for survival can no longer be considered crimes; especially in light of the immoral attitudes and behavior that created the entire scenario in the first place.

The neoliberal ways are just the latest technique for effecting dispossession and enclosure when the elite feel the rest of the world have made too much progress.

The best thing about poor is that I don’t have to associate with rich people.