Today (January 22, 2026), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the latest labour force…

Australian labour market – improving modestly but much more fiscal stimulus is required

The latest data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics – Labour Force, Australia, August 2020 – released today (September 17, 2020) shows that employment rose by 0.9 per cent as the economy struggled to shift back into growth mode. In part, the moderate result was due to the impact of the Stage 4 restrictions in Victoria as that state dealt with the second virus wave. Victoria was the only state or territory to endure negative employment growth in August. As the virus situation is coming under control and the lockdowns are easing, Victoria will rebound fairly quickly – how far depends on the damage done during the closures. The lack of external migration is also seeing the labour force growth moderate significantly, which allowed unemployment to decline by 86.5 thousand on the back of the modest employment boost. Participation also rose. The reality is that if we take a broader view of the labour underutilisation rate (adding in the hidden unemployment who have left the labour force since March) to the official unemployed and underemployed, we find around 19.5 per cent of the available labour supply is not working in one way or another. Any government that oversees that sort of disaster has failed in their basic responsibilities to society. It must increase its fiscal stimulus and target it towards large-scale job creation. My overall assessment is: (a) The current situation can best still be described as near catastrophic; (b) The Australian labour market needs massive fiscal policy intervention targetted at direct job creation; (c) The pre-pandemic need for a fiscal stimulus of around 2 per cent has changed to a fiscal stimulus requirement of several times that; (d) The Federal government’s attempts to date have been seriously under-whelming and we will soon see the results of their withdrawal of the unemployment benefit supplement (a ridiculous decision); and (e) Any government that oversees that sort of disaster has failed in their basic responsibilities to society.

The summary ABS Labour Force (seasonally adjusted) estimates for August 2020 are:

- Employment increased 111,000 (0.9 per cent) – Full-time employment increased 36,200 and part-time employment increased 74,800.

- Unemployment decreased 86,500 to 921,800 persons.

- The official unemployment rate decreased 0.7 points to 6.8 per cent.

- The participation rate increased by 0.1 points to 64.8 per cent.

- Aggregate monthly hours worked increased 1.6 million hours (0.1 per cent).

- Underemployment fell 7.1 thousand but remained at 11.2 per cent because the fall was around the same increase in the labour force. Overall there are 1,506.8 thousand underemployed workers. The total labour underutilisation rate (unemployment plus underemployment) decreased by 0.7 points to 18 per cent. There were a total of 2,428.6 thousand workers either unemployed or underemployed.

Employment increased 111,000 in August 2020

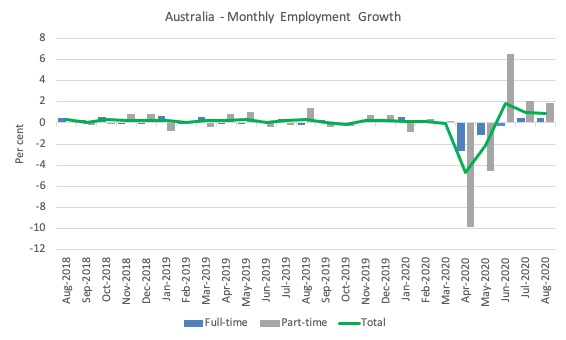

1. Employment growth was positive – 111,000 and the rate of growth was stable (0.9 per cent).

Since March it has now fallen by -413.6 thousand (-3.2 per cent).

2. Full-time employment increased 36,200 and part-time employment increased 74,800.

The following graph shows the month by month growth in full-time (blue columns), part-time (grey columns) and total employment (green line) for the 24 months to August 2020 using seasonally adjusted data.

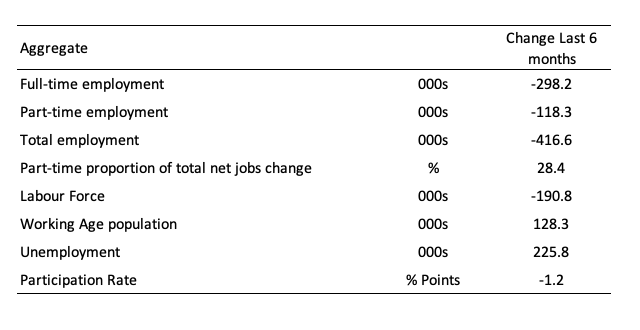

The following table provides an accounting summary of the labour market performance over the last six months.

As the monthly data is highly variable, this Table provides a longer view which allows for a better assessment of the trends.

Assessment:

1. Both the demand- and supply-side have contracted for the same reason – a collapse of employment opportunities. The labour force reduction is less severe than the employment fall, which is why official unemployment has risen.

2. Total employment has fallen by 416.6 thousand and full-time employment losses have dominated. That is a major worry.

3. While official unemployment has risen by 225.8 thousand, hidden unemployment has risen substantially given the labour force has shrunk by 190.8 thousand on the back of a 1.2 points drop in participation.

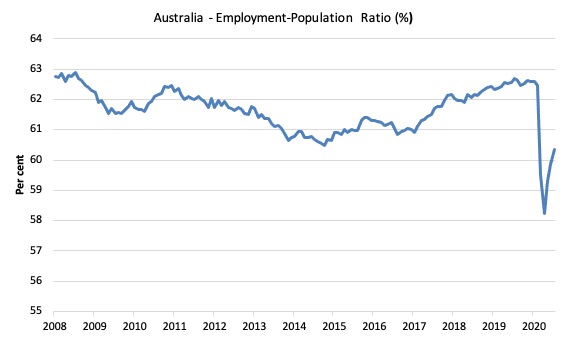

Given the variation in the labour force estimates, it is sometimes useful to examine the Employment-to-Population ratio (%) because the underlying population estimates (denominator) are less cyclical and subject to variation than the labour force estimates. This is an alternative measure of the robustness of activity to the unemployment rate, which is sensitive to those labour force swings.

The following graph shows the Employment-to-Population ratio, since June 2008 (the low-point unemployment rate of the last cycle).

It fell with the onset of the GFC, recovered under the boost provided by the fiscal stimulus packages but then went backwards again as the Federal government imposed fiscal austerity in a hare-brained attempt at achieving a fiscal surplus in 2012.

The ratio rise by 0.5 points in August 2020 to 60.3 per cent. The ratio is now 2.5 points below pre-GFC peak in April 2008 of 62.9 per cent.

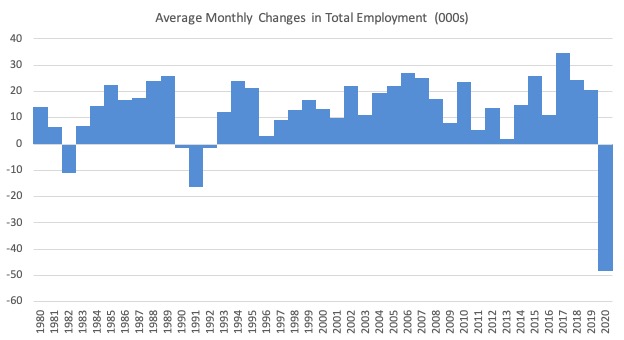

To put the current monthly performance into perspective, the following graph shows the average monthly employment change for the calendar years from 1980 to 2020 (to date).

1. The labour market weakened considerably over 2018 and that situation worsened in 2019.

2. 2020 is off the scale (average employment change so far of -48.2 thousand).

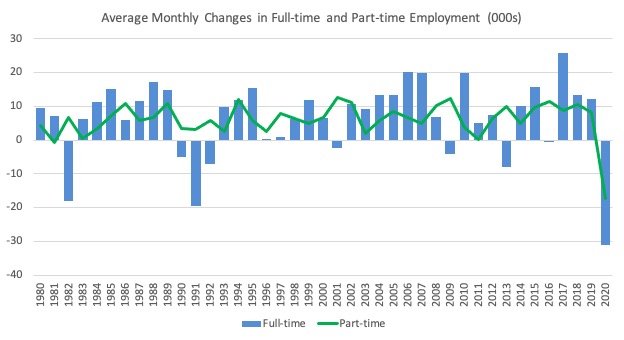

The following graph shows the average monthly changes in Full-time and Part-time employment (lower panel) in thousands since 1980.

The interesting result is that during recessions or slow-downs, it is full-time employment that takes the bulk of the adjustment. Even when full-time employment growth is negative, part-time employment usually continues to grow.

However, this crisis is different because much of the employment losses are the result of lockdowns and enforced business closures in sectors where part-time employment dominates.

But the continuing worsening of the full-time employment situation signals that the demand-side impacts are spreading more widely.

Impact of Stage 4 lockdown in Victoria

The ABS noted that:

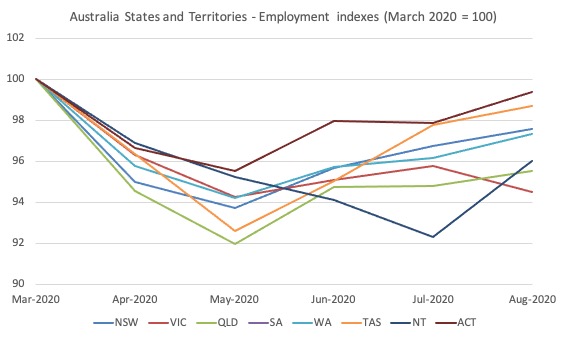

Until August, many of the changes in employment and hours worked had been broadly similar across states and territories. However, the Stage 4 restrictions in Melbourne (and Stage 3 restrictions in regional Victoria) during August resulted in a divergence in labour market outcomes between Victoria and the rest of Australia …

In seasonally adjusted terms, all states and territories recorded a decrease in employment in both April and May. In June and July, all states and territories saw increases in employment except the Northern Territory. In August, the Northern Territory recorded the largest increase (up 4.6%), while Victoria was the only state or territory to record a decrease (down 1.3%)

The following graph shows the impact on employment in Victoria as the State 4 restrictions took hold.

With the restrictions easing next week in Melbourne and already eased in Regional Victoria, that situation will improve next month, although given the timing of the survey (second-week of the month) we will need to wait for the October data release to really understand the situation.

Unemployment decreased 86,500 to 921,800 persons or 6.8 per cent

The official unemployment rate fell by 0.7 points to 6.8 per cent as the growth in the labour force of 48 thousand was outstripped by the growth in employment of 111 thousand.

The participation rate rose by 0.1 points as more jobs opened up again.

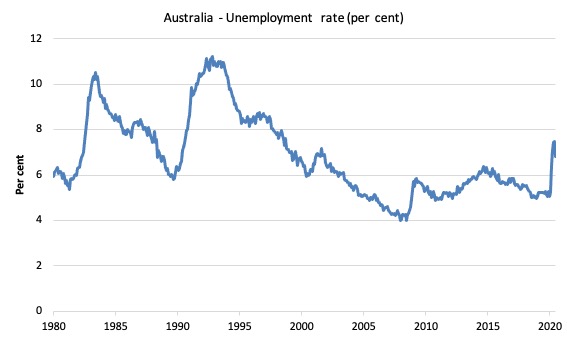

The following graph shows the national unemployment rate from January 1980 to August 2020. The longer time-series helps frame some perspective to what is happening at present.

Assessment:

1. There is clearly still considerable slack in the labour market that could be absorbed with further fiscal stimulus.

2. The government is choosing to allow this rise in joblessness from March to persist.

Broad labour underutilisation decreased by 0.7 points to 18 per cent in August 2020

The results for August 2020 are (seasonally adjusted):

1. Underemployment fell 7.1 thousand as the lockdown eased a little.

2. The underemployment rate was constant at 11.2 per cent (given the labour force growth).

2. Overall there are 1506.8 thousand underemployed workers.

3. The total labour underutilisation rate (unemployment plus underemployment) decreased by 0.7 points to 18 per cent.

4. There were a total of 2,428.6 thousand workers either unemployed or underemployed.

5. The rise in the broad underutilisation rate has been driven by the rise in unemployment, which suggests a longer-lasting crisis – jobs are being shed rather than workers being put on shorter time.

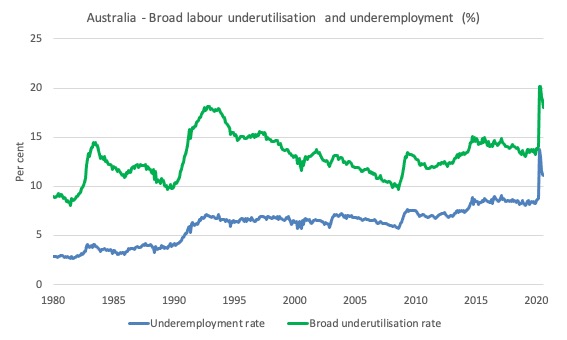

The following graph plots the seasonally-adjusted underemployment rate in Australia from January 1980 to the August 2020 (blue line) and the broad underutilisation rate over the same period (green line).

The difference between the two lines is the unemployment rate.

The three cyclical peaks correspond to the 1982, 1991 recessions and the more recent downturn.

The other difference between now and the two earlier cycles is that the recovery triggered by the fiscal stimulus in 2008-09 did not persist and as soon as the ‘fiscal surplus’ fetish kicked in in 2012, things went backwards very quickly.

The two earlier peaks were sharp but steadily declined. The last peak fell away on the back of the stimulus but turned again when the stimulus was withdrawn.

If hidden unemployment (given the depressed participation rate) is added to the broad ABS figure the best-case (conservative) scenario would see a underutilisation rate around 19.4 per cent at present. Please read my blog post – Australian labour underutilisation rate is at least 13.4 per cent – for more discussion on this point.

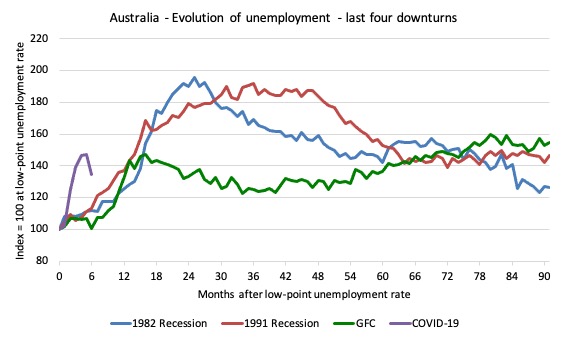

Unemployment and broad labour underutilisation indexes – last four downturns

The following graph captures the evolution of the unemployment rates for the 1982, 1991, GFC and COVID-19 downturns.

For each episode, the graph begins at 100 – which is the index value of the unemployment rate at the low-point of each cycle (June 1981; December 1989; February 2008, and January 2020, respectively).

We then plot each episode out for 90 months.

For 1991, the peak unemployment which was achieved some 38 months after the downturn began and the resulting recovery was painfully slow. While the 1982 recession was severe the economy and the labour market was recovering by the 26th month. The pace of recovery for the 1982 once it began was faster than the recovery in the current period.

During the GFC crisis, the unemployment rate peaked after 16 months (thanks to a substantial fiscal stimulus) but then started rising again once the stimulus was prematurely withdrawn and a new peak occurred at the 80th month.

The COVID-19 downturn, while in its early months, is obviously worse than any of the previous recessions shown.

The graph provides a graphical depiction of the speed at which each recession unfolded (which tells you something about each episode) and the length of time that the labour market deteriorated (expressed in terms of the unemployment rate).

After five months, the unemployment had risen from 100 to:

1. 111.6 index points in 1982.

2. 111.2 index points in 1991.

3. 106.7 index points in the GFC.

4. 134.3 index points currently (and note the point below about participation rate declining)

Note that these are index numbers and only tell us about the speed of decay rather than levels of unemployment.

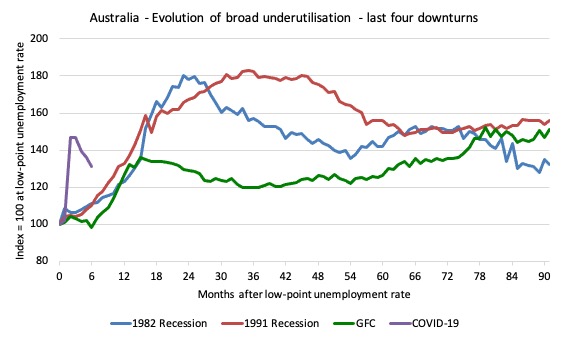

The next graph performs the same operation for the broad labour underutilisation rate (sum of official unemployment and underemployment).

Teenage labour market improves as lockdown eases in August 2020

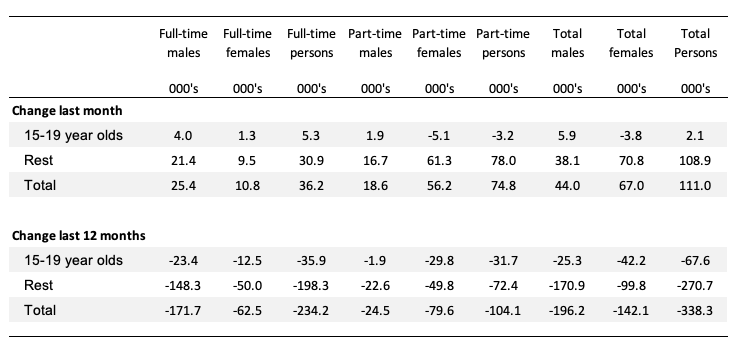

1. Total teenage net employment rose by 2.1 thousand in August 2020 (0.3 per cent) as the low-wage service sector continued to reopen.

2. Full-time teenage employment rose by just 5.3 thousand (4.1 per cent) and part-time employment fell by 3.2 thousand (0.7 per cent). That is a mixed message. With the low-wage service sector opening up a bit more, one would have expected the part-time opportunities for teenagers to expand quickly.

3. The teenage unemployment rate fell by 4.6 points 17.8 per cent on the back of a sharp decline in participation (2.7 points). These aggregates are volatile and it is not clear what led to the participation drop.

The following Table shows the distribution of net employment creation in the last month and the last 12 months by full-time/part-time status and age/gender category (15-19 year olds and the rest).

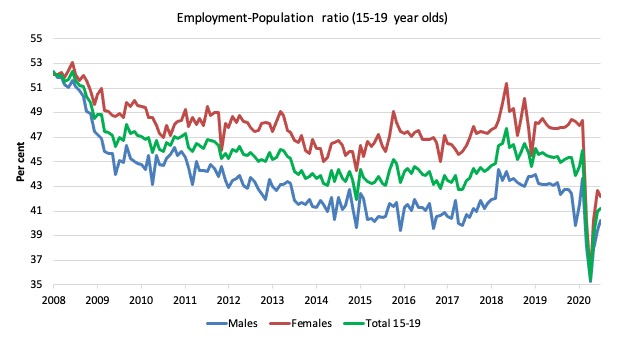

To put the teenage employment situation in a scale context (relative to their size in the population) the following graph shows the Employment-Population ratios for males, females and total 15-19 year olds since June 2008.

You can interpret this graph as depicting the loss of employment relative to the underlying population of each cohort. We would expect (at least) that this ratio should be constant if not rising somewhat (depending on school participation rates).

The absolute loss of jobs reported above has impacted more on females than males.

1. The male ratio has fallen by 12.1 percentage points since February 2008 and 3.4 points since March 2020.

2. The female ratio has fallen by 10 percentage points and 6.2 points since March 2020.

3. The overall teenage employment-population ratio has fallen by 11.1 percentage points and 4.8 points since March 2020.

4. In proportional terms, despite the improvement in June, this remains a devastating result for teenagers.

Aggregate participation rate increased by 0.1 points to 64.8 per cent

The rise in the labour force participation rate means that that the labour force grew by 130 thousand. Given employment only rose by 114,7000, the return of workers into the labour force also pushed up the unemployment pool by 15,700.

This always happens in the early stages of a recovery as the supply-side adjusts to the increased employment opportunities.

The labour force is still below the March 2020 level by 235.2 thousand and those workers will return as employment rises, which will place a further strain on official unemployment.

By how much would unemployment have changed had the participation rate had not risen?

We can make two calculations:

1. Just the monthly implication.

2. The implication of the participation rate being below its most recent peak of 66.2 per cent in August 2019.

The labour force is a subset of the working-age population (those above 15 years old). The proportion of the working-age population that constitutes the labour force is called the labour force participation rate. Thus changes in the labour force can impact on the official unemployment rate, and, as a result, movements in the latter need to be interpreted carefully. A rising unemployment rate may not indicate a recessing economy.

The labour force can expand as a result of general population growth and/or increases in the labour force participation rates.

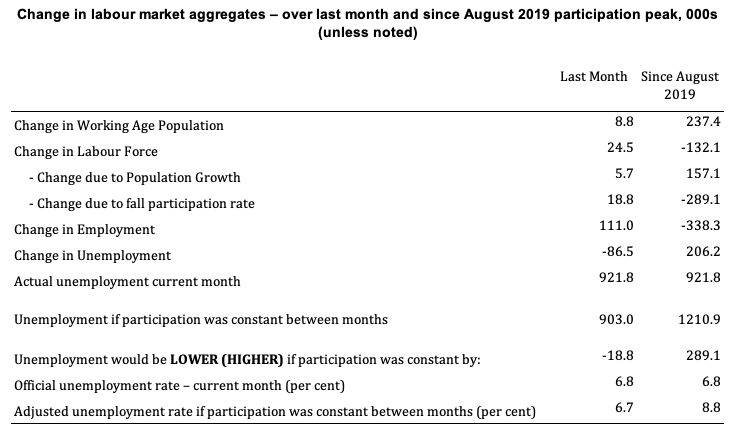

The following Table shows the breakdown in the changes to the main aggregates (Labour Force, Employment and Unemployment) and the impact of the rise in the participation rate.

The change in the labour force in August 2020 was the outcome of two separate factors:

- The underlying population growth added 5.7 thousand persons to the labour force. The population growth impact on the labour force aggregate is relatively steady from month to month but has slowed in recent months due to the border restrictions and the impact they have had on migration rates; and

- The rise in the participation rate meant that there were 18.8 thousand workers re-entering the labour force (relative to what would have occurred had the participation rate remained unchanged).

- The net result was that the labour force rose by 24.5 thousand.

Assessment:

1. If the participation rate had not have risen in July, total unemployment, at the current employment level, would have been 885.1 thousand rather than the official count of 903 thousand as recorded by the ABS – a difference of 18.8 thousand workers (the ‘participation effect’).

2. Without the rise in the participation rate in August 2020, the official unemployment rate would have been 6.7 per cent (rounded) rather than its current value of 6.8 per cent).

3. Hidden unemployment thus fell by 18.8 thousand.

4. The situation is worse if we consider the collapse since August 2019. The labour force has shrunk by 132.1 thousand and the unemployment rate would be 8.9 per cent rather than 6.8 per cent had those workers not dropped out of the labour force as a result of inadequate job opportunities.

5. If we add the change in hidden unemployment back into the broad labour underutilisation rate currently estimated to be 18 per cent, we would get a total wastage rate of 19.5 per cent.

And, as I keep concluding – policy failure.

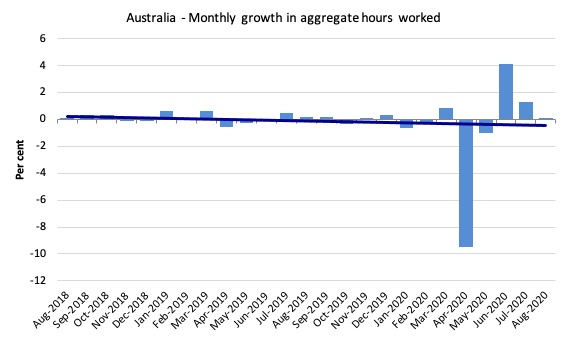

Hours worked increased 1.6 million hours (0.1 per cent) in August 2020

As the lockdown eases, hours worked are returning – but this month’s increase was negligible.

The following graph shows the monthly growth (in per cent) over the last 24 months.

The dark linear line is a simple regression trend of the monthly change – which depicts a decreasing trend. Even before the coronavirus crisis struck, the trend was downwards.

Conclusion

My standard monthly warning: we always have to be careful interpreting month to month movements given the way the Labour Force Survey is constructed and implemented.

The August 2020 data reveals that the Australian economy continued to recover somewhat as the government eased the strict lockdown on businesses.

However, the pace of improvement was modest and the impact of the Stage 4 restrictions in Victoria as that state dealt with the second virus wave was evident.

Victoria was the only state or territory to endure negative employment growth in August. As the virus situation is coming under control and the lockdowns are easing, Victoria will rebound fairly quickly – how far depends on the damage done during the closures.

My overall assessment is:

1. The current situation can best still be described as near catastrophic.

2. The Australian labour market needs massive fiscal policy intervention targetted at direct job creation.

3. The prior need for a fiscal stimulus of around 2 per cent has changed to a fiscal stimulus requirement of several times that.

4. The pre-pandemic need for a fiscal stimulus of around 2 per cent has changed to a fiscal stimulus requirement of several times that; (d) The Federal government’s attempts to date have been seriously under-whelming.

5. Any government that oversees that sort of disaster has failed in their basic responsibilities to society.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2020 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

“3. The prior need for a fiscal stimulus of around 2 per cent has changed to a fiscal stimulus requirement of several times that.”

Just to clarify this a bit for me- so previously there was a need for increased deficit spending of about 2% of GDP by the Australian government? Or possibly, tax decreases of somewhat more than that, holding spending constant?

Can I think of that as the usual state of affairs? As in the government will usually need to run a deficit in order to maintain close to full employment conditions?

If the Job Guarantee had been up and running, prior to this pandemic, would you expect that no additional deficit spending by the government, beyond JG wages, would be required for economic purposes during this ordeal?

Jerry, in a pandemic, I envisage the government telling everyone to stay home, while ensuring maintenance of supply and distribution of essentials, and simply paying everyone’s bills for the duration of the pandemic.

Trying to organise a JG in a pandemic would likely be impractical.

Neil, see Some lessons from history for the design of a coronavirus fiscal intervention

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=44558

“There is no shortage of productive jobs that can be done which would be ‘safe’ in this social distancing era but would provide valuable outputs to society.”

Neil, I agree with your assessment of our current situation. But might not this pandemic provide a wonderful opportunity to put a JG into place, one which could seamlessly pay people to stay home as well as go to work, in sync with changing public health concerns?

How do you have one of the biggest monthly rises in employment on record (I presume ate least) – including large numbers of full-time jobs – with hardly any growth in hours worked?

I guess there should have been a massive fall in the number of people receiving JobSeeker? (taking timing lags into account)

Does this mean that the new Weekly Payroll Jobs data which showed no indication this, may be of limited practical value?

Bill and CoFEE will no doubt be scrutinizing the data thoroughly but the suggestion floating around at present is that there was a huge surge in gig economy workers – they are not captured in the single-touch payroll survey and often work low numbers of hours.

Australia’s next boom – precarious employment.

Government seems to be set on throwing lots of money towards their RTO mates to train people for jobs that don’t exist or to attach a training subsidy to a current employee that already has the required skills.